Research Article

Research Article

Luxury Strategy Comparing SPA Brands and Luxury Brands — Flagship Store Strategy for Large Store Location —

Shin’ya Nagasawa1* and Norihiro Suganami2

1Graduate School of Business and Finance, Waseda University, Japan

2Tanseisha Co. Ltd., Japan

Shin’ya Nagasawa, Graduate School of Business and Finance, Waseda University Tokyo, Japan.

Received Date: December 11, 2020; Published Date: January 12, 2021

Abstract

Not only luxury brands, but also fast fashion brands such as ZARA and H&M have successfully opened flagship stores in prime locations such as Ginza, Tokyo. The market-entry strategy via flagship stores appears to be successful, as numerous companies have adopted it. However, for this strategy to work, it is important to consider and verify not only the place, but also the product, price, and promotion aspects. This study systematically investigates the flagship store strategy by comparing the strategies of luxury brands, represented by Chanel and Louis Vuitton, and those of SPA (Specialty store retailer of Private label Apparel) brands, represented by ZARA, developed by the Spanish Inditex Corporation.

Keywords: store location, flagship store, brand building, luxury strategy

Introduction

Not only luxury brands, but also SPA (Specialty store retailer of Private label Apparel) companies such as H&M and Forever 21 have found success in opening flagship stores in prime locations like Ginza, Tokyo. As many companies are pursuing a market-entry strategy based on such stores, it has now become a conventional means for expanding overseas; however, research attention has thus far focused solely on the opening of stores in such prime locations and the luxurious stores themselves.

Moreover, unlike other Japanese retailers who are struggling to expand overseas, UNIQLO has been achieving success in overseas expansion with the opening of flagship stores [1-5]. This strategy was originally adopted by Western luxury brands when they entered Japan. It is surprising and interesting that UNIQLO, which is a fast fashion brand that is opposite to the luxury brands in the US and Europe in terms of product, price, and brand image, also follows the same flagship store strategy as these Western luxury brands. However, does the fact that such companies are not only focusing on advertisements and promotions, but also spending a large amount of capital to open flagship stores, mean that such stores are taking on an aspect of brand building that cannot be achieved through advertising and promotions alone?

Using a case analysis of UNIQLO’s flagship store strategy, Nagasawa and Suganami [6,7] concluded that that it is important for a company’s flagship store strategy to contribute to brand building using not only the element of place (location), but also the elements of product, price, and promotion, to heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association. However, it could be argued that the systematization of this strategy is not fully supported by the study of one case alone.

Thus, Nagasawa and Suganami [8,9] sought to verify our hypothesis through a research method that, in addition to a review of the relevant literature, includes interviews with Satoru Citation: Shin’ya Nagasawa, Norihiro Suganami. Luxury Strategy Comparing SPA Brands and Luxury Brands— Flagship Store Strategy Page 2 of 8 for Large Store Location —. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 7(3): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000665. DOI: 10.33552/JTSFT.2021.07.000665. Matsuzaki, managing director and head of the Overseas Operations Division (at the time, President), at Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd., the company that operates MUJI [5,10-12].

Based on the above, this study addresses the respective strategies of Chanel and Louis Vuitton, which are representative luxury brands, and ZARA, which is a representative of SPA companies. By analyzing the flagship stores of these brands that have opened stores in the Ginza and Omotesando areas of Tokyo, we clarify the characteristics of flagship stores that are common to both luxury brand and fast fashion brand flagship stores.

Previous Studies on Flagship Stores

Previous studies define flagship stores as follows. Nagasawa, et al. [13] claim that while fashion-related books tend to describe flagship stores as ‘stores that carry all of a brand’s products’ [14,15], they should be defined as ‘stores that carry all of a brand’s products while exhibiting the brand’s essence’. Kozinetsa [16,17] suggests that the three general characteristics of flagship stores are that (1) they carry a single brand, (2) they are directly managed by the brand, and (3) they are operated more with the intention of brand building than with the singular intention of profits. Moore, et al. [18,19] argues that luxury brands’ flagship stores play an important role in market entry strategies.

Based on previous studies, it can be said that brand building is an objective of flagship stores and that these stores play an important role in market entry. However, previous studies have not covered the methods of market entry. Using UNIQLO and MUJI as examples, Nagsawa, et al. [7,9] clarified the characteristics and methods of the flagship store strategy but did not study the objectives of flagship stores or their location and design. MUJI and UNIQLO carry products in the mid-price range and can be viewed as being on almost the opposite end of the spectrum from luxury brands.

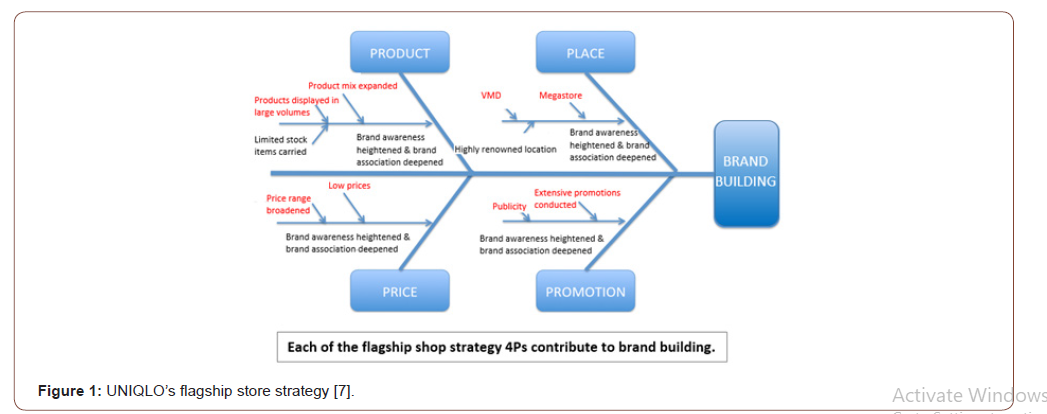

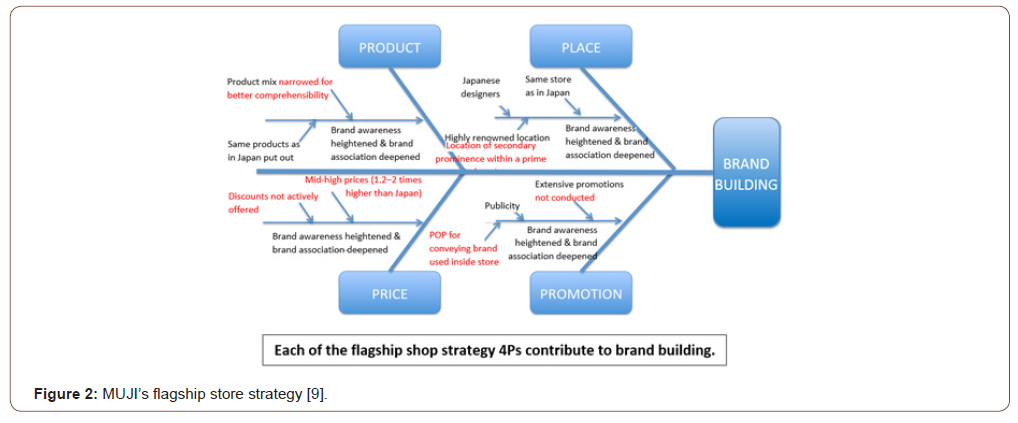

Based on the analysis results, Figures 1 and 2 show the characteristics of the flagship store strategies of UNIQLO and MUJI as cause and effect diagrams.

UNIQLO is active in all 4Ps. By contrast, MUJI is located in a prime location, but rather than having a large-scale roadside store on the first floor, it tends to open a medium-scale store on the upper floors, such as the third floor. It is characterized by having stores in so-called ‘primary and secondary areas’. In addition, MUJI focuses on communicating the brand, does not actively expand or promote products, and does not reduce prices.

Although both strategies share the feature of opening stores in prominent locations, the strategies differ in that UNIQLO opens stores in definitively prime locations, while MUJI opens stores in prime locations, albeit in areas of secondary prominence. When the two strategies are considered in terms of other additional factors, they differ completely. However, when looking at the cause and effect diagrams, although there are differences in individual aspects, there are also many points in common, which can be attributed to the fact that each aspect is devised to contribute to brand building.

In other words, it can be seen that for both brands, each of the 4Ps of the flagship store strategy leads to brand building as a whole.

The two companies are similar in that, in terms of market entry strategies revolving around flagship stores, both have mechanisms in every category of the 4Ps for making consumers aware of the brand, and both also have mechanisms for conveying a Japanese image. Therefore, adding the brand value of the nation of Japan is also considered to be effective in developing overseas operations.

However, both MUJI and UNIQLO are Japanese companies, and there are other cases such as ZARA (Inditex, Spain), which is a representative global SPA company. It is necessary to clarify the essence of the flagship store strategy and its method by examining the case of ZARA and luxury brands in Japan [20].

Research Purpose and Method

As in the previous study, a flagship store is defined as ‘a store that exhibits the brand’s essence’ while the flagship store strategy is defined as ‘a market entry strategy revolving around a flagship store that contributes to brand building by using all of the elements of product, price, place (location), and promotion to heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association.’

We conducted field and literature surveys on fast fashion and luxury. In Nagasawa and Suganami [2,4], the flagship store strategy suggested that each of the 4Ps increased brand awareness and strengthened brand association. By conducting a survey from perspective of the 4Ps, we clarify the common points and differences between flagship stores.

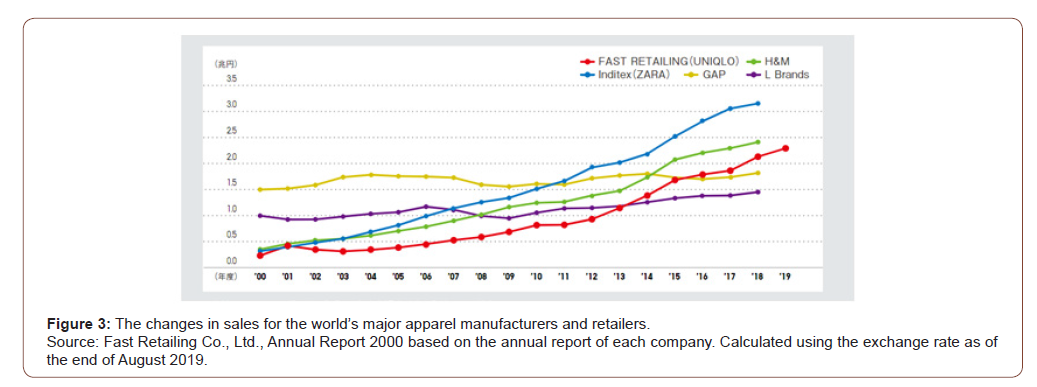

Regarding SPA brands, Figure 3 shows the changes in sales for the world’s major apparel manufacturers and retailers [1].

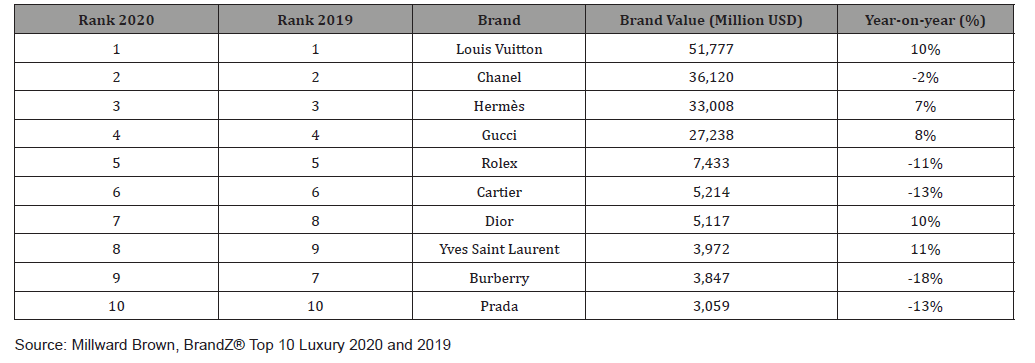

Luxury brands ranked in the Top 100 Best Global Brands 2020 by Interbrand [21] are shown in Table 1. Also, the Top 10 luxury brands in Millward Brown BrandZ 2020 [22] are shown in Table 2.

Considering the above data and based on considerations comparing luxury and non-luxury brands by Kumagai and Nagasawa [23-26], and Nagasawa [27-29], stores of the following brands have been selected as the subjects of this study as they fulfil the conditions of global fashion brands with flagship stores operating in Japan.

1. The Ginza store of Zara owned by Inditex, is a fast fashion brand founded in Spain, which later expanded its operations globally. Inditex is a SPA that proactively invests in its stores but does not conduct promotions.

2. The Ginza store of the luxury brand Chanel, which has its own building in one of the best areas of Ginza; it operates its flagship store together with a restaurant and event space.

3. The Omotesando flagship store of Louis Vuitton had established the standard for flagship stores by establishing them early on.

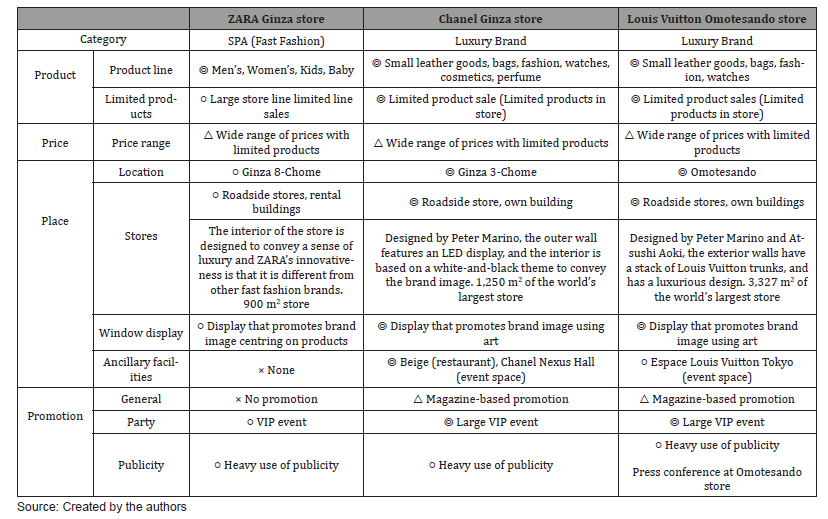

A field survey was periodically conducted between 2012 and 2018. The contents of the field survey and a literature survey have been compiled and presented in Table 3.

Table 1:Characteristic of the patients with AED withdrawal (n=162).

Table 2:The Top 10 luxury brands in Millward Brown BrandZ 2020.

Table 3:Flagship store s of Ginza and Omotesando brands.

The fast fashion brand Zara and the luxury brands Chanel and Louis Vuitton sell products at a wide range of prices; their respective flagship stores have many common features, with characteristics of both fast fashion and luxury brands displayed in the stores.

Field Survey Results

Product

All of the brands deploy their full line of products at their respective flagship stores. Zara, for instance, deployed their new baby line on September 6, 2012, previously available only online, to coincide with the renovation of their Ginza store.

Louis Vuitton has also taken steps to deploy its products to its flagship store, such as its watch line in 2002 when the store was opened. Along with its full line of products, the store also serves as a location for the launch of new products. Each brand also displays products that are limited to their flagship stores.

Zara displays its New York Collection, which is limited to 30 stores globally, and Chanel launched a bag (designed by Karl Lagerfeld) in 2011, when its Ginza store was renovated, the sales of which were limited to the store.

Louis Vuitton also launched the sale of watches and bags in cooperation with America’s Cup to match the opening of its flagship store, which resulted in a queue of 1,400 people waiting to enter the store on its opening day.

Price

Each brand has various products available for a wide range of prices, and many of them limited. Zara’s flagship store’s limited products are sold for approximately 20% more than their general products. For these products, Zara is not necessarily attempting to appeal to customers through low prices despite being a fast fashion brand.

Place (location, store)

All of the stores are located in top-notch fashion streets in Ginza and Omotesando, visited by many tourists, and hence called super prime locations.

All the three stores directly manage shops facing the street with areas typically larger than those of normal-size stores. Zara has sufficient space to sell its full range of products, while Chanel and Louis Vuitton have not only enough area to sell their full range of products but also enough space to accommodate and guide visiting VIPs and host in-store cultural events, which require an area much larger than that of a brand shop within a department store.

The Zara store was designed in-house. The design itself emphasizes the points that Zara relies on to differentiate itself from other fast fashion brands, namely a sense of luxury, an awareness of trends, and the sense of speed that allows it to move from designing a product to displaying it in stores within two weeks.

The Chanel Ginza store was designed by the famous designer Peter Marino. The outside walls use 700,000 LEDs, which display animations that symbolize Chanel, such as the CC mark, the camellia, tweed, and so on, as well as event announcements and seasonal images. Also, the sides of the central pathway on the first floor are entirely devoted, with the exception of the entrances, to window displays featuring art that is changed every few weeks. Within the store, the first to third floors are sales floors. The store design is based on the Chanel brand colors of white and black. The fourth floor is the Chanel Nexus Hall, used for hosting concerts and art events. The building also houses a restaurant run in collaboration with Alain Ducasse, the ‘Beige Alain Ducasse Tokyo’, where the staff uniforms were designed by Karl Lagerfeld, and the interior, in addition to the store itself, was designed by Peter Marino. The restaurant can be used even by those who are not Chanel customers, allowing anyone to have a Chanel brand experience.

The Louis Vuitton Omotesando store was designed by the Japanese architect Jun Aoki as part of an architectural competition. It features a façade design with trunks that represent Louis Vuitton; the trunks are piled on top of one another, and once inside the store premises, customers can shop while taking a ‘small trip’ moving from one trunk to another. The window displays, just as with Chanel, feature artworks that change every few weeks. In 2011, an art space called ‘Espace Louis Vuitton Tokyo’ was opened on the 7th floor. Art events have been held there periodically ever since.

All these stores make use of exterior and interior designs that are cognizant of communicating each brand’s worldview, even if the methods of doing so differ. The shared aspect of the exteriors is the proactive use of the brand’s icons to increase brand recognition, while in the interior, the brand icon is set into every detail, thereby strengthening the mental association of the brand with the worldview that it communicates. In particular, the luxury brands Chanel and Louis Vuitton use their two stores, including the exhibition and other space within them, to strengthen their relationships with consumers and heighten the brand associations of their respective brands. The number of luxury brands that position themselves next to eateries has increased since the opening of the Chanel Ginza store’s restaurant, Beige Alain Ducasse Tokyo, and this also shows how interactions with consumers can be deepened, and brand associations, that is, consumers’ identification with the brand, can be strengthened.

Promotion

Zara held a party at its Ginza store the day before the reopening of the renovated Ginza store. A movie taken at the time of this party was uploaded to the Zara homepage together with videos of parties that took place in the Zara flagship stores of New York and London, created based on the same concept as the Ginza store. Images of this party were picked up by the fashion media. By establishing a promotion site on the web shared by all of the flagship stores in Citation: Shin’ya Nagasawa, Norihiro Suganami. Luxury Strategy Comparing SPA Brands and Luxury Brands— Flagship Store Strategy Page 6 of 8 for Large Store Location —. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 7(3): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000665. DOI: 10.33552/JTSFT.2021.07.000665. each of the world’s major cities, such as New York, London, and Moscow, and Zara’s sharing of these pictures on their web page provided consumers who did not participate in these parties with a brand experience through the images.

When the Chanel Ginza store opened, a large-scale fashion show event was allowed to be held in the public space in Hibiya Park. The space that could normally accommodate only a few hundred people had to accommodate an audience of several thousand. A festival organized around the opening of the flagship store was thus experienced by thousands of people. This not only increased awareness of the brand but also strengthened brand association in the minds of consumers who were now more aware of their connection with the brand. On the web, pictures illustrating the main features of the flagship as well as the stories set in the flagship store were posted.

The day prior to the opening of the Louis Vuitton Omotesando store was spent in a lavish manner. The opening party held in the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery in the outer garden of the Meiji Shrine was particularly widely discussed and featured in every type of media pertaining to business or fashion as well as in talk shows. The media further reported that 1,400 items had been lined up as limited products at the time of opening, meaning that consumers were ultimately made aware of the Louis Vuitton brand image and the opening of the flagship store without the need for any announcements. Photographs of flagship stores in every major city in the world and introduction of the concepts behind their creation together with information about the city where the store was located were uploaded on the web page. This was a strategic promotional act for Louis Vuitton, which has adopted travel as a brand universe.

Discussion

Although there are differences between the flagship stores of the fast fashion brand Zara and the luxury brands Chanel and Louis Vuitton, there are many similarities as well.

In terms of products, Zara features a line of limited products, while Chanel and Louis Vuitton not only have lines of limited products but also offer product lines exclusively limited to the Chanel Ginza and Louis Vuitton Omotesando stores.

In terms of locations, Chanel and Louis Vuitton have their own buildings that house their flagship stores and project their brand identity into every facet of their buildings. Comparatively, as Zara leases space within a building, its efforts are limited to embellishing the exterior. This indicates a difference in scale in comparison to the luxury brands. Also, there is a major difference in terms of secondary facilities. Zara has enough space to feature its full range of products and throw an opening party but has no facilities to host activities unrelated to sales, such as event spaces or restaurants. In comparison, Chanel has both an event space and a restaurant, while Louis Vuitton has an event space but no restaurant. With respect to place, timing is crucial in terms of buying a suitable plot or block of land or assessing rent costs immediately upon their becoming available when the brand decides to establish a flagship store. In this context, the conglomerates which own several brands are at an advantage, such as LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, as they have the financial strength to purchase land to establish a new store.

Although there are many points of commonality between Zara and Chanel and Louis in relation to business promotion strategies, large differences can be seen in the scale of business promotion events and extent of media coverage of those events. Nevertheless, as flagship stores come under direct management, are larger than general stores, and hold opening parties, as in the case of Zara, or have event spaces, as in the cases of Chanel and Louis Vuitton, they provide locations for continuous interactions with customers.

Luxury brands tend to win over fast fashion brands in terms of product, price, place, and promotions. This does not mean that flagship stores of luxury brands are superior to fast fashion outlets. On the contrary, there is a need for luxury brands to be more conscious of their brand-building initiatives against competition from fast fashion outlets. From the consumer’s point of view, differences exist in terms of both price and brand positioning. It is likely that consumers visiting fast fashion stores offering products at cheaper prices may decide to upgrade their purchase behaviour by visiting flagship stores offering a luxurious ambience and a larger range of products and features that enhance the quality of their shopping experience more than a normal store. It is also possible that consumers may view flagship stores of luxury brands as unapproachable and intimidating on account of simple actions such as a courteous doorman screening visitor before their entry into the store premises.

Professor Jean-Noël Kapferer, considered an authority on luxury brand research, states that “luxury brands do not seek comparative advantage (comparative degree) but rather irreplaceable absolute advantage (highest degree),” in order to make their flagship stores incomparable to the flagship stores of brands such as Zara.

Furthermore, from a managerial point of view, one can say that the differences between flagship stores stem from the differences between their business models. Zara has a business model that involves manufacturing and globally offering a wide range of trendy products at cheap prices to a large consumer base. Its flagship store is built around this rationale. In other words, Zara’s flagship stores are viewed both as a place to build the brand and as a sales location where a variety of products are sold to a large number of customers. In contrast, luxury brands like Chanel and Louis Vuitton have a business model that lays emphasis on adding even more value to top-quality products and offering those value-added products to a limited set of high-end consumers at even higher prices. These brands operate by offering high-price value-added products through avenues such as store space, products, service, and events to a limited number of consumers in flagship stores built to sustain a high-end image of upmarket exclusivity for a rich clientele. Thus, flagship stores of Chanel and Louis Vuitton post lower sales than fast fashion brands because they focus on the brand itself along with sales. Flagship stores of luxury brands stand out because of the premium they place on aesthetics and luxurious ambience, and are thus greatly featured in promotions, but they also appear standoffish and foreboding to consumers unfamiliar of their ambience because to enter flagship stores, you must first go past the doorman standing in front of a heavy door. This dual nature embodies a way of brand building that is unique to luxury brands.

Concluding Remarks

Figure 4 summarizes the flagship store strategies of SPA brands such as UNIQLO, MUJI, and ZARA. Figure 5 summarizes the flagship store strategy of luxury brands such as Chanel and Louis Vuitton.

As shown in Figure 4, there are many cases in which the SPA brand is active in all 4Ps, but there are cases in which strategies differ depending on the brand. In addition, as shown in Figure 5, luxury brands are aggressively implementing all 4Ps.

As shown in Figures 4 and 5, consumers’ brand awareness increases through promotion and place (location), which leads to consumers visiting the store. Moreover, product, price, and place (store) all work to heighten consumers’ brand awareness and strengthen brand association at the store, where consumers actually come into contact with the brand. Based on these factors, it can be said that the flagship store strategy contributes to brand building as the 4Ps all work to heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association.

According to the survey of the three stores, there were many similarities, but the degree differed by brand. In other words, when developing a flagship store strategy, it is not necessary to aim for a definitive flagship store such as the luxury brand flagship store considered in this case and previous studies. The flagship store strategy is aimed at brand building, but the degree of the marketing mix for brand building needs to be changed according to each brand’s positioning and business model.

Generally speaking, one could consider only the place (location/ distribution) element involved in 4P analysis, but it can be argued that a normal store strategy and a flagship store strategy differ on aspects other than simply location and distribution. Each element of the 4Ps is different for the two types of stores and plays a role in establishing brand awareness and strengthening brand association.

It is important for flagship store strategies to contribute to building a strong brand by incorporating all of these elements into the marketing mix.

Acknowledgment

This paper is financially supported by Grant-in-Aid (B) No. 18H00908 of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fast Retailing Co., Ltd (2020) Annual Report 2000-2020.

- Yanai T (2004) Issho Kyuhai (One Win Nine Losses). Shinchosha Publishing, Tokyo, Japan.

- Yanai T (2009) Seiko wa Ichinichi de Sutesare (Forget about Success in One Day). Shinchosha Publishing, Tokyo, Japan.

- Matsushita K (2010) Yunikuro No Shinkaron (Evolution Theory for UNIQLO). Business-sha, Inc, Tokyo, Japan.

- Saito T (2018) UNIQLO vs ZARA, Nihon Keizai Shimbun-sha, Tokyo, Japan.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2018) Flagship Shop Strategy for Brand Building: Case of UNIQLO. Proceedings of 2018 Global Marketing Conference at Tokyo: 1144-1156.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2019) Luxury Strategy by Daily Fashion Brand of UNIQLO: Flagship shop strategy for large store location. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 4(2): 1-6.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2020) Flagship Shop Strategy for Brand Building: Case of MUJI, Proceedings of 19th International Marketing Trends Conference (IMTC2020). Academic Research Session Retail Strategy and Retail Brands: 1-17.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2020) Luxury Strategy by Simple and Pleasant Life-Style Brand of MUJI: Flagship store strategy for large store location. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 6(4): 1-7.

- (2020) Ryōhin Keikaku HP.

- Watanabe Y (2009) Mujirushi Ryōhin no “Kaikaku,” (Management Reform of Mujirushi Ryohin). The Shogyokai Publishing, Tokyo, Japan.

- Watanabe Y (2012) Mujirushi Ryōhin Sekai Senryaku to Keiei Kaikaku (Mujirushi Ryohin’s Global Strategy and Management Reform). The Shogyokai Publishing, Tokyo, Japan.

- Nagasawa S (2009) Jiba-Dento Kigyō no Keiken Kachi Sōzō: Keiken-kachi wo Umu Gijutsu-keiei (Premium Strategy of Local and Traditional Industries of Japan: Building customer experience and technology management), Doyukan, Tokyo, Japan.

- Japan Association for Promotion of Fashion Education (1996) Fashion Brand Strategy. Japan Association for Promotion of Fashion Education, Tokyo, Japan.

- Japan Association for Promotion of Fashion Education (2008) Fashion Business. Japan Association for Promotion of Fashion Education, Tokyo, Japan.

- Kozinetsa RV, Sherrya JF, DeBerry-Spencea B, Duhacheka A, Nuttavuthisita K, et al. (2002) Themed flagship brand stores in the new millennium: theory, practice, prospects. Journal of Retailing 78(1): 17-29.

- Kozinetsa RV (2009) Themed flagships brand store in new millennium: theory, practice, prospects, in Tony T, Brown R (edts), Flagship Marketing: Concepts and places, Routledge, London, UK, pp.17-29.

- Moore CM, Doherty AM, Doyle SA (2009) Flagship stores as a market entry method; the perspective of luxury as a market entry fashion retailing. European Journal of Marketing 43: 140-142.

- Moore CM, Doherty AM, Doyle SA (2010) Flagship stores as a market entry method: the perspective of luxury as a market entry fashion retailing. European Journal of Marketing 44(1/2): 139-161.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2020) Flagship Store Strategy for Brand Building: Comparison between Luxury Brands and SPA Brands. Proceedings of 2020 Global Marketing Conference at Seoul: 500-513.

- (2020) Interbrand. Best Global Brands.

- Brown M (2020) BrandZ Top 100 Most Valuable Global Brands.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2016) The Influence of Social Self-Congruity on Japanese Consumers' Luxury and Non-luxury Apparel Brand Attitudes. Luxury Research Journal 1(2): 128-149.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2017) Consumers' perceptions of store location effect on the status of luxury, non-luxury, and unknown apparel brands. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 8(1): 21-39.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2017) The Effect of Selective Store Location Strategy and Self-Congruity on Consumers' Apparel Brand Attitudes Toward Luxury vs. Non-luxury. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 8(4): 266-282.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2019) Psychological Switching Mechanism of Consumers' Luxury and Non-luxury Brand Attitude Formation: The Effect of Store Location Prestige and Self-congruity. Heliyon 5(5)e01581: 1-12.

- Nagasawa S (2015) Brand Management, In: Su Mi Dahlgaard-Park (ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Quality and the Service Economy (Book Chapter), SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.39-43.

- Nagasawa S (2016) Japan Has Developed Luxury Brands. Marketing Review St. Gallen 33(5): 58-67.

- Nagasawa S (2019) On the Future of Fetish/ Affective Value. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 3(3): 1-4.

-

Shin’ya Nagasawa, Norihiro Suganami. Luxury Strategy Comparing SPA Brands and Luxury Brands— Flagship Store Strategy for Large Store Location —. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 7(3): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000665.

-

Store location; Flagship store; Brand building; Luxury strategy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.