Review Article

Review Article

On the Future of Fetish/ Affective Value

Shin’ya NAGASAWA*

Graduate School of Business and Finance, Waseda University Tokyo, Japan

Shi’nya Nagasawa, Graduate School of Business and Finance, Waseda University Tokyo, Japan.

Received Date: July 26, 2019; Published Date: August 02, 2019

Abstract

This paper describes our research on the future of fetish value and affective/Kansei value such as Relation between Affective/Kansei Value and Fetish Value of Karl Marx, Reasons Why Regular Brands Do Not Apply Affective/Kansei Value, Reasons Why Japanese Brands Do Not Use Fetish Value and Affective/Kansei Value in Marketing, Pursuing the Luxury Strategy, and Importance of the Luxury Strategy

Keywords: Fetish value; Affective/Kansei value; The luxury strategy

Relation Between Affective/Kansei Value and Fetish Value of Karl Marx

While more philosophically complex, if deconstructed into sensation and emotion, the emotional side of affective/Kansei value, represented by our sense of luxury and status [1], equates almost directly with Marx’s fetish value. Of the values which consumers subjectively perceive as separate from the use value of a product, it definitely maps closer than the sensory side of affective/Kansei value, such as taste or smell. The two are perceived differently, however; whereas affective/Kansei value is a psychological value perceived by the consumer subjectively, fetish value represents deviation between the product’s original value and market price-a characteristic value peculiar to capitalism.

Karl Marx (1818-1883) does not attribute any mysterious characteristics to the use value of a commodity; these result from its exchange value. Through the social division of labor, the social characteristics of labor are reflected in commodities, and the ratios used for exchange are decided according to human relations, namely, the ratio of productivity of labor in producing each commodity (e.g. how many can be produced in an hour). Accordingly, the various properties assigned to commodities by the social division of labor are automatically treated as being natural, intrinsic properties of that commodity itself. This is commodity fetishism: a reification peculiar to capitalist production in which commodities assume a godlike mystique. In non-capitalist production, the social division of labor is reified, not goods. Division of labor becomes the subject of the reification when exchanged for commodities [2].

Reasons Why Regular Brands Do Not Apply Affective/Kansei Value

Regular brands make no attempts at applying fetish value and affective/Kansei value to transform their products into the kinds that sell and draw rabid fanbases regardless of price because they don’t know how due to lack of experience. As a result, they think it can’t be done or never think to try.

To take an example, to earn a million yen selling watches, you could sell 10,000 people a 100-yen watch each, or you could sell one watch to one person for one million yen. It’s a question of which choice you take. You might say that talk is cheap, but in fact implementation is another story. So, what makes it so hard?

In our example, the 100-yen watch, and million-yen watch are both watches, but they are clearly different products. They have to be. If you can’t explain exactly why the million-yen watch costs so much and what sets it apart from the 100-yen watch when asked, you won’t sell any.

We are talking about two different products. The prices are different, naturally-one at 100 yen and the other at one million yen. Given price, they are also distributed through different channels: a 100-yen store can sell 100-yen watches, but if they were to put a million-yen watch on display alongside the other watches, no one would buy it. It wouldn’t fit. You have to sell it in different stores and venues. Promotion is different as well; the price alone can sell a 100-yen watch, but you need to sell the story and history of a million-yen watch to have any hope of selling one. Thus, the biggest issue at hand is that the clientele for 100-yen watches and million-yen watches are different. Here, innovation takes the form of changing clientele. Innovation is not restricted to technology; it applies to all facets of business.

Promotion is different as well; the price alone can sell a 100- yen watch, but you need to sell the story and history of a millionyen watch to have any hope of selling one. Thus, the biggest issue at hand is that the clientele for 100-yen watches and million-yen watches are different. Here, innovation takes the form of changing clientele. Innovation is not restricted to technology; it applies to all facets of business.

Targeting luxury requires innovation at all levels: the product, the price, distribution, promotion, and crucially, clientele. Everything changes. Many will instinctively recoil at the mention of “innovation”; even if totally convinced, they can’t bring themselves to action. After all, innovation is hard to do [3].

Reasons Why Japanese Brands Do Not Use Fetish Value and Affective/Kansei Value in Marketing

There are three main possibilities for why local brands like Inden-ya (established in 1582), traditional companies like Chiso (established in 1555), Toraya (established in 1525 or so) and brands like Toyota, despite the latent luxury potential of its Lexus moniker, make no attempts at fetish value or affective/Kansei value.

These three are as follows:

Modest and virtuous dispositions

Here, the Japanese pre-disposition not to beat one’s own drum may get in the way. Statements such as “My product is amazing” or “Look at how great I am!” are shameful and discouraged.

Long-standing local and traditional brands are particularly wont to depend on their reputation: those who know, know. However, the reverse is equally true: those who don’t know, don’t.

The “Tap Water Philosophy”

Konosuke Matsushita, the namesake who founded Panasonic predecessor Matsushita Electric Housewares Manufacturing Works in 1918, espoused what is known as the “Tap Water Philosophy,” that a company’s mission is to distribute goods cheaply enough to breed happiness. This philosophy helped the spread of mass production for appliances, building Matsushita Electric into a leading Japanese manufacturer. Matsushita is deified in Japanese business circles for his pioneering efforts in methods that persist in today’s corporate management, such as segmenting the business into divisions with responsibility for managing profits independently for each factory cluster. Fast-forwarding to the 2000s, however, the same Panasonic lost big to competitors in flat panel TVs. Today, the Tap Water Philosophy has been reinterpreted to devise lifestylechanging value-added products, such as beauty appliances. The Japanese business god’s notion of affordable quality products is seeded deeply in Japanese manufacturers. Leveraging fetish value and affective/Kansei value to sell at higher price points stands diametrically opposed to this philosophy and is thus rejected out of hand.

Quality control

The U.S. introduced quality control to Japan in the post-war era as a means of quantifying things. Japan rejected the concept, citing that things are subjective and emotional and cannot be objectivized or quantified.

To them, Japanese QC and monozukuri (manufacturing and assembling) were justified in the zenith that was 1980s Japan. Kaoru Ishikawa, progenitor of the quality control circle, liked to use the phrase “mohkatte komaru (profitable, more profitable, then at a loss for doing)” to describe QC, which means that excess profits make a mess of quality control. Lowering defect rates in turn reduces the defective products that need fixed or eliminated, thus lowering costs. The practice of equating quality with defect rates long persisted in Japan, keeping affective/Kansei quality from catching on.

Pursuing the Luxury Strategy

The four P’s come up frequently in marketing. The first two are straightforward: product & price. Next is place, which represents distribution channels-where the product is sold. The final P is for promotion. With that background, here is my explanation.

In marketing for regular products, the product is supposed to have just enough quality. Too much quality would make it expensive, after all. Relative quality & functional benefit are a good thing. In contrast, luxury strategies aim to build a product of exceptional quality and craftsmanship with a story. In technical terms, this is referred to as absolute quality, affective/Kansei quality, or experiential value.

In terms of price, cheaper is generally better. Low cost offers a relative advantage over other products. Luxury products, however, are high-priced the world over. I must stress though that the brand itself is reasonably priced, commensurate with the effort put into creating the product. It has an absolute value that renders comparison to other products immaterial.

Distribution will present an issue. In the end, you can’t put a million-yen watch on the shelf with 100-yen watches and expect it to sell. The staff at the store wouldn’t know how to sell it, for one thing. Thus, you, with your own employees who are thoroughly versed in your commitments to your craft, will inevitably have to sell the product themselves in company-run stores. If not company stores, limited distribution channels can be used.

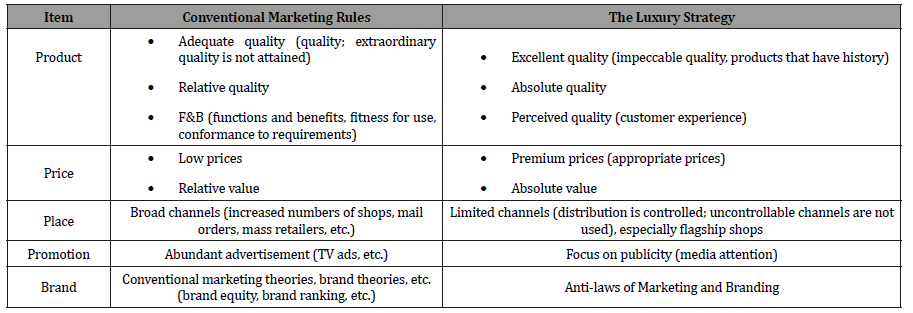

Promotion is another point of focus for luxury brands. Luxury branding runs counter to traditional marketing and brand theory. No amount of TV commercials will work. Any advertisements will be image advertising or celebrity testimonials (Table 1).

Table 1:Conventional marketing vs the luxury strategy [4].

Marketing for mass consumer goods started in the US. Meanwhile, the luxury strategy was pioneered in Europe, developed by conglomerates such as P&G that dominated worldwide. Small, family-run businesses, mainly in France and Italy, grew into worldwide brands in less than half a century. The same creative method can be applied to many businesses in most all cultural spheres.

There is another important reason for the success of luxury brands. Each of the European luxury brands is a well-established store in its respective country. Louis Vuitton was established in 1854. They are a long-established Parisian luggage store celebrating their 165th year in 2019. Or take Bulgari, established in 1884. Bulgari is an old Roman jeweler celebrating its 135th year in 2019. These stores, whether managed by the same family generation after generation or long-standing local or traditional industries, are jumping onto the world stage as today’s luxury brands.

In Japan, however, the long-standing companies and the local, traditional industries are almost all on the verge of collapse. Their sales are in steady decline. Artisans get older and older with no successors. This is more than just a visual: this is reality.

And yet there are long-standing Japanese businesses like Toraya (500 years) and Chiso (464) with even more history than their European counterparts. These businesses need to learn from the luxury brands leveraging their history as a management resource.

Importance of the Luxury Strategy

Here, we will explore from the consumer mentality what makes the luxury strategy of targeting a brand that will sell and grow a fanbase despite its price so important.

Clearly, consumption in Japan is being polarized into highand low-price items, and high-priced luxury brands will sell even when consumption is low. Also, there are clear winners and losers even among luxury brands. All of this can be reduced to a single cause: corporate effort. Let’s look at this phenomenon from the perspective of consumer mentality.

When faced with insecurity, people instinctually tend to choose the safe option. We will err on the side of safety if we doubt that our income will rise, or that we may not get enough from our pension, or that disaster may strike. There are two safe choices in consumption. The first is to save money and attempt to buy the cheapest item. People in this camp will tend to shop at stores like Uniqlo and Shimamura. The second choice is to buy quality items that will last. Luxury brand purchases fit into this camp.

Also, when facing losses and gains of similar scale, aversion to loss wins. In behavioral economics, this is referred to as loss avoidance. For example, the pain of losing 1,000 yen is 2-2.5 times greater than the joy of finding 1,000 yen on the street.

In terms of behavior, the mentality behind loss avoidance leads to what is called status quo bias. Change may be for the better or worse. When loss avoidance kicks in, we tend more to avoid the loss than we welcome gains, effectively strengthening our resolve to maintain the status quo. Thus, employees tend to follow company customs, incumbents tend to be re-appointed, workers tend to stay in the same workplace, and people tend to buy the same brands, over and over. Such status quo bias is said to be a kind of inertia [5].

Meanwhile, the world is overflowing with products and services to the point that consumers can’t decide which choice is best due to excess information. They need a convincing reason to decide. In behavioral economics, this is termed a reason-based choice. According to this theory, if a person can satisfactorily rationalize a choice, they will ignore any inconsistency in that decision. Thus, high-priced luxury brands are likely to continue selling in spending slumps because those who choose to buy such items are satisfied with the quality, security, and story of the brand, compelled to buy it at all costs.

Even when markets are down and no one can sell anything, cheap foodstuffs, staple products and long-life products continue to sell.

This also is explained by status quo bias: consumers are avoiding the loss from switching brands, satisfied in the fact that this or that is a staple or long-life product when choosing to buy. Likewise, the line between winners and losers amongst high-priced luxury brands is being drawn based upon whether the product is an iconic staple or long-life product, has an iconic factor, whether the brand has a rich story, and whether all of this is conveyed to the consumer. We have much to learn from luxury brands.

It is significant for Japanese companies, especially long-standing companies, local companies, and family-owned companies in Japan which are not yet global luxury brands to learn the Kansei/fetish value and luxury strategy, i.e. what luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton has done for these 40 years or so [6,7].

Acknowledgement

This paper is financially supported by Grant-in-Aid (B) No. 18H00908 of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nagasawa S (2002) Product development relating Kansei, Tokyo, Japan Publishing Service.

- Marx K (1867) Das Kapital I.

- Nagasawa S (2015) Building high-ticket brands that sell, Tokyo, Japan.

- Nagasawa S (2016) Japan Has Developed Luxury Brands, Marketing Review St. Gallen 33(5): 58-67.

- Tomono N (2006) Behavioral Economics, Tokyo, Kobunsha, Japan.

- Nagasawa S (2017) Japanese Kodawari (elaboration) fascinates the World, Tokyo, Kaibundo Publishing, Japan.

- Nagasawa S (2015) Brand Management In: Dahlgaard-Park SM (edts), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Quality and the Service Economy (Book Chapter), SAGE Publications, USA, pp. 39-43.

-

Shin’ya NAGASAWA. On the Future of Fetish/ Affective Value J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 3(3): 2019. JTSFT.MS.ID.000564.

-

Fetish value, Kansei value, Brands, Luxury Strategy, Marketing, Consumer, Capitalism, Commodity

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Relation Between Affective/Kansei Value and Fetish Value of Karl Marx

- Reasons Why Regular Brands Do Not Apply Affective/Kansei Value

- Reasons Why Japanese Brands Do Not Use Fetish Value and Affective/Kansei Value in Marketing

- Pursuing the Luxury Strategy

- Importance of the Luxury Strategy

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References