Research Article

Research Article

Affinity Groups in Educational Settings to Promote Inclusive Excellence: A Systematic Literature Review

Sam Steen1*, Jordon Beasley2, Kara Ieva3 Zikun Li1 and Lisa Atkins1

1George Mason University, Virginia

2Augusta University, Georgia

3Rowan University, New Jersey

Sam Steen, College of Education and Human Development, George Mason University, Virginia

Received Date:October 17, 2025; Published Date: October 24, 2025

Abstract

There is a scant amount of research on group counselling in educational settings, and groups that focus on race, culture, and identity (e.g., agency and marginalization) are even less prevalent. This article presents a systematic literature review using a variety of databases including, Academic Search Complete, Education Research Complete, ERIC, Google Scholar, JSTOR, and APA PsycInfo during 2023-2024. The aims of this study were to 1) show that affinity groups are a viable option for promoting inclusive excellence in schools, 2) describe the process of how affinity groups promote inclusive excellence through the lens of power, privilege, and intersectionality, and 3) illuminate the benefits affinity group participation can offer to teacher and student participants. Researchers offer a theoretical framework, exhaustive descriptive table, and qualitative snapshot of themes gleaned from the findings. The article concludes with implications for practice, research, and policy.

Keywords:Affinity groups; Small group counselling; School counselling; Inclusive excellence

Introduction

The flagship organization for school counselling professionals (SCs) has a primary mission to provide professional development, enhance school counselling programs, and study (e.g., research) effective school counselling practices (American School Counsellor Association [ASCA], n.d.). One resource to guide SCs’, researchers’, and policy makers’ understanding of group counselling efforts is ASCA’s position statement on group counselling which reflects a tone that this modality facilitated by school counsellors can attend to the needs of all students across a myriad of dimensions. Within this document, it is directly stated that groups have been shown to improve academic achievement, social-emotional learning, and career development, therefore it is integral to implementing the ASCA National Model for School Counselling Programs [1]. What is missing from this position statement is clarity on how groups address challenging topics and ongoing atrocities stemming from systemic failures within schools impacting marginalized students, families, and staff that have been ongoing for decades.

Now as ever, student needs continue to include academic concerns, however, within the U.S. exploring race, culture, and ways this intersects with academic contexts is crucial and necessary. While the ASCA position statement on groups includes commentary that “groups create a climate of trust, caring, understanding and support which enables students to share their concerns with peers and the school counsellor” [1], scholar-practitioners are demonstrating that groups contribute in much more meaningful ways [2]. Ongoing research efforts demonstrate that groups are used to attend to student growth and development in a proactive manner [3]. Additionally, there are isolated examples of groups promoting mental health and education while mitigating injustices and inequities in school environments (Sam Steen*). Group counselling is one powerful way to build a positive community where all members within the group, and within the system in which the group is situated, can thrive [2]. In this article, the authors conduct a systematic literature review of articles within educational settings when affinity groups are the program or intervention employed.

Group Counselling Systematic Literature Reviews

There are several systematic literature reviews about group counselling that offer insight on how to frame the current study. First, the effects of group counselling were studied with a primary focus on adults from several different countries across the globe (Yusup et al., 2020). These authors used a systematic literature review, but only included articles that used quantitative methodology. In the present case our focus is on students and staff. In order for the article to be included in our review, the group must have taken place within a school setting. Additionally, the articles included need not be limited to quantitative methods. Next, a systematic literature on groups that took place within junior high schools was discovered [4]. This study limited its search to the years 2016 to 2020. The findings presented were illustrious, demonstrating that there are different types of problems that groups can successfully address such as emotional maturity, low self-esteem, smoking behaviour, inability to cope, and poor social skills. These findings, while interesting, are not new with the exception of smoking cessation [5]. One limitation in this study is that while the researchers offered different treatment strategies within the groups there was not a focus on race and culture. More recently, researchers conducted a systematic literature review on groups in school settings that explored achievement and therapeutic factors (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins). These authors built on a prior study (Sam Steen*) that focused on achievement outcomes primarily. One drawback in both of these reviews is that these authors excluded studies that did not use quantitative strategies. Further, while those reviews considered the racial makeup of the group leaders and participants, they focused mainly on presenting the outcomes. In the present study, articles that use affinity groups with student or teacher participants in school settings are included whether they use quantitative, qualitative or mixed designs. We believe approaching this review in a flexible manner is not a limitation but an opportunity to gain insight on what schools are doing to address race and culture. Below we discuss how affinity groups are defined within the literature to inform the current study.

Affinity Groups Defined

There are numerous definitions for affinity groups found in the literature within and beyond school settings. Within school settings definitions include but are not limited to ‘‘caucus groups’’ which are essentially meetings where students from a specific social identity come together to reflect on related personal experiences [6]. Affinity groups have also been defined in relation to staff members (e.g., educators of colour) as a critical space that centres healing and collectively processes racial trauma [7].

Outside of the school environment, affinity groups have been described as employee resource groups (ERGs) integral to the corporate landscape since the 1970s (Boston College Centre for Work & Family, n.d.). Moreover, research beyond educational environments highlighted that these types of groups offer a myriad of benefits to employees, including fostering a sense of belonging, enhancing engagement, and improving retention [8]. Specifically, within healthcare settings, affinity groups have demonstrated value in providing support for diverse staff, promoting cultural competence for members across the racial spectrum, and fostering healthy and welcoming environments [9]. Despite the documented advantages of affinity groups in corporate and healthcare sectors, their implementation in school settings remains limited (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins) and for school counselling stakeholders in particular understanding the impact affinity groups can make poses a great potential [10]. Given the success in other contexts, it is reasonable to assume that affinity groups could have similarly transformative impacts in educational settings for the members involved.

Affinity Groups in Schools

The current research on affinity groups, while insightful, is nascent. Therefore, the aim in this study is to corroborate or expand prior research that explored the impact of groups combating racial injustice in schools. For instance, in an earlier study conducted by the primary authors, there was a small yet salient discrepancy in the idea that affinity groups are used to fight against racism and discrimination that some students and teachers may encounter. It was found that at times SCs avoided or were hesitant to create, implement, and evaluate affinity groups that focused on race, gender, or other aspects of identity to lessen the chances of community upheaval (Authors). Upon further probing, in actuality, SCs in this study were providing a space for these topics to be explored, but they were strategic in how they did so, often in a way that was subtle to avoid misunderstandings. While initially surprising, the current socio-political climate impacting schools today warrants this posture. That said, these findings spur the need to dig deeper as there are contrary examples of several studies using affinity groups [10] whereby topics like racial identity development and the exploration of what it means to be white, as an example, are happening in direct and impactful ways. Particularly noteworthy in this case, is the participants’ concern about the “all White group optics” despite how beneficial they were for their own personal and professional growth (p. 11).

Moreover, previous research suggests that group counselling programs and interventions can impact the school’s overall environment to be inclusive. For example, we know that within the Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) framework groups are not limited to Tier II but also occur in Tier I (Sam Steen*). After further investigation, affinity groups, or groups that are described and understood as a gathering of students who share common elements of identity to explore, celebrate, embrace and reflect on their experiences related to these social locations, can easily be situated within Tier 1 because of the flexibility to meet the far-reaching needs of students by allowing them opportunities to choose when and how often to attend while also removing the stigma that may be associated with attending a group intended as a way to “fix” a student or to intervene on behalf of one’s problem (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins).

We are beginning to uncover how influential groups really can be. To illustrate, affinity groups in schools tend to organize organically as a response to hostile conditions or unwelcoming environments whereby minoritized folks seek out or create these spaces as a means to foster well-being despite conditions of subjugation (Dech, 2022). As a counter-space to white heteronormativity within schools, we can also understand these spaces as “sites where deficit notions of people of colour can be challenged and where a positive climate can be established and maintained” (Solórzano et al., 2000, p. 70). This review aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the structure and benefits of affinity groups in educational settings, extending beyond race and student-related academic outcomes, to avoid constraints imposed by our own positionality and expertise. Because the literature on affinity groups specifically designed for school environments remains limited [10], this systematic review of the existent literature could enhance these efforts by generating innovative and impactful recommendations for school counsellors, researchers, and policymakers. Such an approach would help leverage the potential of affinity spaces in schools to support and uplift all students, regardless of racial or cultural background.

Affinity Groups and Educational Excellence

Refusing to settle for antiquated notions of students of colour and those from marginalized backgrounds, we aim to highlight the opportunities that affinity groups can offer based on successful research and practice. The tensions in school settings are ongoing, and groups that aim to foster inclusive excellence, defined in this case as a framework for understanding and pursuing excellence in education through diversity and inclusion [11]. can provide the support needed for student and staff excellence. Groups that collectively address students’ identity, agency, and strengths need not be limited to 6-8 sessions over lunch in schools (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins). Furthermore, the term “affinity” group need not be limited to conventional definitions of the term. In fact, connections to Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) and other creative and impactful gatherings of students and/or teachers in group settings that intentionally utilize group dynamics are applicable even if not referred to as “affinity” groups. Affinity groups can be implemented at a schoolwide level to promote the mental health and well-being of both students and staff. These groups are commonly associated with outcomes such as increased agency, leadership development, and enhancements in academic, career, social, interpersonal, and cognitive domains [12]. Moreover, affinity groups contribute to educational excellence by addressing systemic barriers to student success while also supporting the social and emotional needs of both students and staff (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins). The impact of these groups can be analysed through the following mechanisms:

Promoting Equity and Inclusion. Schools that implement affinity groups demonstrate a commitment to equity by acknowledging and addressing the unique challenges faced by students and staff from marginalized backgrounds. By centring diverse voices, affinity groups help cultivate a more inclusive school culture (Banks, 2015).

Improving Student Engagement and Achievement. Studies show that students who participate in affinity groups report higher levels of school engagement and motivation (Harper, 2012). This increased engagement correlates with improved academic performance and reduced dropout rates.

Enhancing Leadership and Advocacy Skills. Affinity groups empower students to take on leadership roles within their schools, equipping them with skills in advocacy, conflict resolution, and community organizing. These experiences help prepare students for future civic engagement and professional success (Ginwright & Cammarota, 2002).

Conceptual Framework

This study has been conceptualized using Critical Systems Theory ([CST]; Watson & Watson, 2011), a framework designed to analyse and address the complex, interconnected issues present within educational systems. Originating from the integration of systems theory (Bertalanffy, 1968) and critical social theory (Horkheimer, 1937), CST was developed in the mid-twentieth century by a multidisciplinary group of scholars (Watson & Watson, 2011).

Central to the CST approach is critical analysis with the intent of advancing equity, justice, and empowerment. CST enables researchers to utilize a systems-thinking approach, integrating both critical and systemic perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of how schools, policies, communities, and societal structures interact and influence diverse populations.

CST was amply selected for this study as it brings a dual perspective, combining the objective “hard systems” approach with the subjective and cultural insights of “soft systems” thinking. This duality allows researchers to explore both the systemic and human aspects of the educational context for today’s students. Central to CST is the advancement of social justice and empowerment. For example, social justice within CST emphasizes advocacy and action to dismantle oppressive structures and create opportunities for marginalized groups, aligning with the goals of this study.

Drawing on CST, the current researchers apply the lens of power, privilege, and intersectionality (PPI) to critically examine the implementation and impact of affinity groups in educational settings. PPI provides a framework to explore how systemic inequities manifest and intersect within school environments, highlighting the experiences of those who are often marginalized. As CST encourages researchers to interrogate how systems reproduce oppression and privilege, this framework is particularly suited to exploring the potential of affinity groups to disrupt inequitable practices and foster inclusivity. The components of the PPI framework are defined next.

Power: In an educational context, power refers to having influence, authority, or control over students and/or resources (Murray et al., 2020). Society and schools within society are affected by many different power structures: patriarchy, white supremacy, heterosexism, cissexism, and classism are only a few (Powell, 2022). Together they interact into a larger oppressive system that disenfranchises those with limited access to institutional knowledge and power.

Privilege: Recognizing privilege is a critical element in the process of achieving racial equity. Society and schools grant privilege to students because of certain aspects of their identity that can include but are not limited to race, class, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, language, geographical location, ability, religion, and diagnosis (Ferguson & King, 1997). In school settings, privilege can operate on a personal, interpersonal, cultural, and institutional level and gives advantages, favors, and benefits to dominant groups at the expense of marginalized groups (Geiger & Jordan, 2013).

Intersectionality: Kimberl´e Crenshaw (1989, 1991) coined the term intersectionality as a framework for conceptualizing how systems of oppression overlap to create distinct experiences for people with multiple identity classifications (e.g., race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, and other identity markers). Within schools, intersectionality frames marginalized students’ overlapping identities and experiences to help them understand the complexity of multiple prejudices and oppression they may face.

Purpose of the Current Study

This study explores the potential of affinity groups in schools,

by addressing the need for research on their utilization and

implementation in these environments using a systematic literature

review. The purpose of this study is to 1) show that affinity groups

are a viable option for promoting inclusive excellence in schools,

2) describe the process of how affinity groups promote inclusive

excellence through the lens of power, privilege, and intersectionality,

and 3) illuminate the benefits affinity group participation can

offer to teachers and student participants. The primary research

question guiding this study is as follows:

1. How are affinity groups used to promote inclusive

excellence in school settings?

The following sub-questions further refine the inquiry:

a. To what extent do affinity groups in school settings

empower diverse populations?

b. To what extent do affinity groups in school settings

leverage privilege for specific populations?

c. To what extent do affinity groups in school settings

recognize and explore intersectionality for diverse populations?

Methodology

Lead Authors’ Positionality

The first three lead authors’ collective positionality poses a unique way to situate the approach to this project. The first three lead authors are all school counsellor educators. In addition, they have conducted multiple studies that involve group counselling in schools (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins). This line of research provides expanded notions of group counselling, how groups are operationalized, how groups are used as well as the impact groups can make on student achievement and behaviour in schools. In the current article, the lead authors aim to advance school counsellors’ ability to contradict assumptions that affinity groups perpetuate racism or segregation. In addition, to conducting scholarship, the lead authors included graduate students at the doctoral level and masters’ level for the fourth and fifth authors respectively. The purpose was to provide research mentorship to these students while receiving help in managing the research data.

Research Team and Research Design

The research team, consisting of all 5 authors, elected to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR) to answer the research questions. An SLR is a structured approach that allows the researchers to methodically identify, analyse, and synthesize existing knowledge on a specific topic [13], which, in this case, is affinity groups in educational settings. This SLR follows the method outlined by Pittway (2008) which includes the following seven key principles: 1) transparency, 2) clarity, 3) integration, 4) focus, 5) equality, 6) accessibility, and 7) coverage. Following the initial search for relevant literature, the research team utilized critical discourse analysis (CDA) to examine and interpret the findings. CDA methodology allows researchers to critically analyse data by incorporating socio-political and contextual factors (Wodak & Meyer, 2009). This qualitative approach is particularly suited for this study, as the concepts of power, privilege, and intersectionality are fundamental to the methodology (Fairclough, 2001).

Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

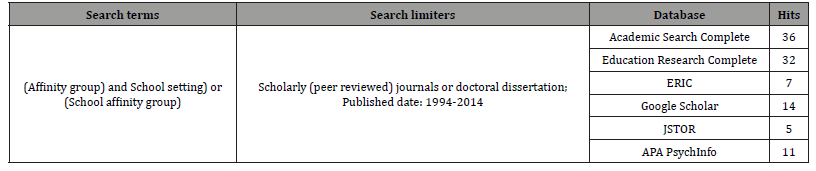

In searching for relevant articles, members of the research team utilized the following data sources: Academic Search Complete, Education Research Complete, ERIC, Google Scholar, JSTOR, and APA PsycInfo. Initial searches were conducted in each database by querying article abstracts with the search terms “Affinity group” AND “School setting” OR “School affinity group.” Search limiters were applied to ensure the literature met the eligibility criteria, restricting results to peer-reviewed journal articles, commentary pieces, and doctoral dissertations. Only literature written in English was included in the analysis. Although specific date ranges were not predefined, the articles retrieved spanned from January 2004 to April 2024. The primary search results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:Search parameters and initial results.

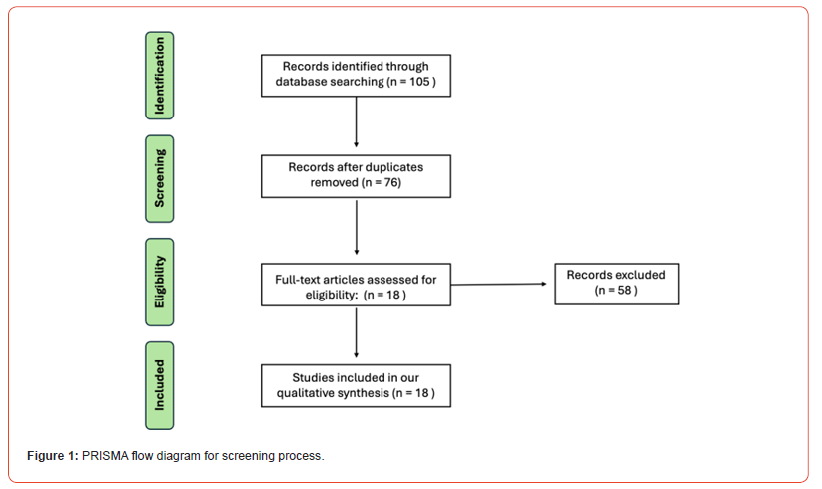

The initial search yielded 105 studies. The fourth and fifth authors conducted the first screening and removed duplicates. This resulted in 76 articles remaining. After this, the entire research team conducted a second screening and a total of 58 articles were excluded as they consisted of non-peer-reviewed works, conceptual articles, or studies conducted outside of K–12 settings. While these excluded articles provided valuable insights, their findings fell outside the scope of the current study. The team then screened each of the remaining articles based on titles and abstracts and 18 articles were identified as potential candidates for review. These articles were then fully assessed for applicability using the following criteria: K–12 educational settings for students or teachers with an age range 6–18 for students, empirical studies, publication in scholarly and peer-reviewed journals or doctoral dissertations, written in English, and alignment with the research questions. Figure 1 presents a diagram of the screening process.

Data Analysis and Inter-rater Agreement

First, one third of the articles (n=6) were reviewed by the members of the research team to generate the study components and establish fidelity in the analysis process. In order to reach consensus in how to examine the articles, each article was independently reviewed and then discussed as a team. Second, in order to reach consensus, the team met to explore how the articles used affinity groups to promote inclusive excellence and/or contributed to the concepts of power, privilege, and intersectionality. Once consensus was reached, the remaining articles (n=12) were assigned to one of the research team members (e.g., first, second or third author). Each article was independently analysed by this member who documented their observations in an Excel spreadsheet organized by the primary research question and its sub-questions. Following the independent reviews, the other two members of the research team (e.g., fourth and fifth authors) cross checked these comments for reliability. Following this process, the entire research team (e.g., all authors) convened numerous times to discuss their findings and refine the results through critical discourse analysis. These collaborative discussions, which totalled approximately 10 hours, allowed the team to achieve 100% interrater reliability.

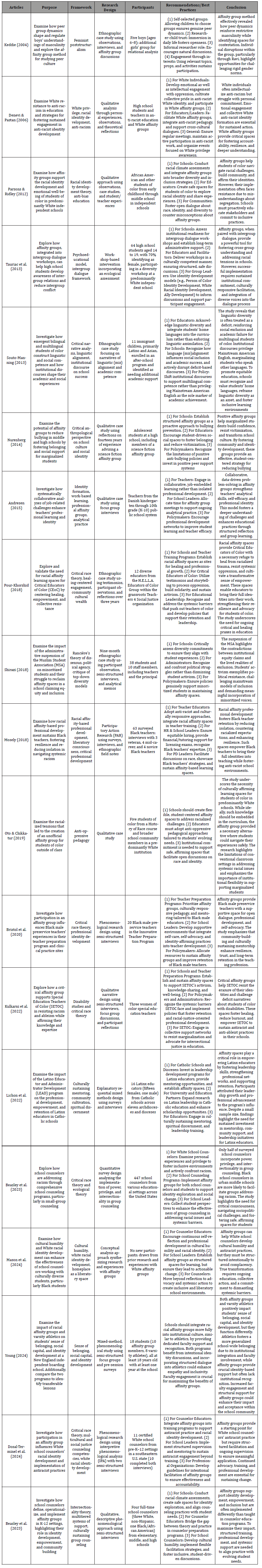

Table 2:Article Summary.

Findings

Summary of Findings in Table 2

Table 2 provides all the details about the articles including the authors and year, the purpose, the framework, the research design, the participants, the recommendations for best practices and a conclusion. In sum the table above reveals key patterns regarding the facilitation, target populations, and origin of the group. While all groups examined were offered within educational environments, facilitation varied, with school counsellors not always serving as the primary leaders. These groups were predominantly implemented at the elementary and high school levels. Many were designed for students yet, a majority of them included teachers, or teachers and students. Specifically, there are 10 articles that had only educators as participants (e.g., teachers or SCs). There were two articles with students and staff both included. And, only seven articles with only students.

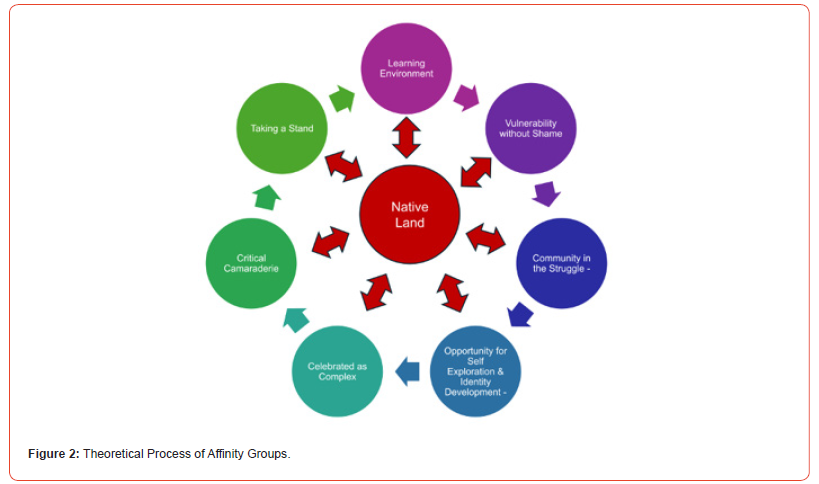

It appears from our examination that the articles show many of the groups emerged in response to broad, systemic needs rather than individual concerns, with some even being initiated by the participants themselves. A closer look shows that 13 of the 18 articles used either identity, critical race theory, intersectionality or variations of these concepts with other theories (e.g., disability, social capital, and ecological) to frame the article. Although affinity groups frequently served marginalized populations, exceptions existed, including instances where the focus was on broader goals such as decolonization and neurodiversity. These findings provide a foundation for understanding the overarching themes that define the structure, purpose, and impact of affinity groups in schools. See Figure 2: Theoretical Process of Affinity Groups.

Building on these insights into the planning, implementation, and evaluation of groups that foster empowerment or challenge oppressive environments, we present qualitative findings that emerged from our critical discourse analysis. Below we present themes that were gleaned from the systematic literature review to inform affinity group counselling practice that fosters inclusive excellence.

Theme 1: Native Land

A salient theme emerging from the literature was the idea of affinity groups as “native land.” Within the articles, this idea of native land was also referred to as a “shelter” and “safe space.” Throughout the literature, the concept of “native land” refers to a psychosocial space where group members report feeling a sense of safety, being celebrated for their uniqueness, and sensing a collective group identity. The rich descriptions within the articles were reminiscent of bell hooks ‘homeplace.’ Homeplace is defined as a place of refuge and resistance within oppressive systems (hooks, 1990). The construct of native land can further be operationalized using the following dimensions identified through qualitative analysis: 1) affirmation of non-normative interests, 2) the legitimization of subcultures, 3) a protective factor within oppressive spaces. Native land is a co-created space where group members feel a sense of refuge and belonging not because of their similarities but in the celebration of their differences.

Theme 2: Celebrated as Complex/

In the article, “Cultivating sacred spaces: a racial affinity group

approach to support critical educators of colour,” one participant

poignantly described her everyday work experience, stating:

“When I’m with my colleagues [at work] I feel like I’m a sliver

of myself [because] they’re fragile, liberal white folks who I have to

come off a certain way with so that they don’t feel attacked, which

makes my identity in relation to them carefully constructed” [14].

She further explains that in her affinity group which fostered healing and empowerment, she can show up fully as herself. The concept of being a sliver of oneself showed up numerous times throughout the literature. During our collective discourse, we defined this recurring theme as “Celebrated as Complex.” This construct is informed by participants’ reflections, which describe it as a profound sense of wholeness, authenticity, and acceptance experienced within their affinity groups. Central to this construct is the rejection of reductive identity frameworks. Instead, participants are acknowledged, valued, and uplifted for the totality of their identities, culmination of experiences, and diverse perspectives. Being celebrated as complex emphasizes being seen, known, and valued in one’s entirety, as opposed to being reduced to a singular, oversimplified aspect of one’s being. This construct asserts that complexity is not only accepted but honoured and appreciated.

Theme 3: Vulnerability without Shame

Emerging next from the literature is the theme of vulnerability without shame. Vulnerability without shame can be operationalized as the ability for participants to express authentic thoughts, feelings, and experiences without fear of judgment or rejection. This construct is rooted in a shared foundation of trust among group participants. All the literature emphasized the critical role of shared trust in fostering a safe space for honest expression. This shared trust becomes the cornerstone of psychological and emotional safety, enabling individuals to share openly without hesitation. One participant succinctly stated, “I have to know that what I’m sharing isn’t going to be used against me later.” This highlights the necessity of mutual respect and discretion within the group dynamic. The opportunity to be vulnerable without shame does not occur instantaneously but develops over time through consistent, genuine rapport, active listening, and mutual openness. Another example of this is illustrated when several new teachers shared their struggle with what they expected of themselves and what they were able to deliver. A professional development program for staff that was coupled with an affinity group space to process the training provided these teachers who mainly identified as Black/ African American, to receive support, empowerment and to learn how to transform the environments in which they were working that benefited both students of colour and white students. Black male teachers described engaging in honest dialogue that helped reveal common practice-related challenges they experienced based on their positionality as preservice male teachers of colour. Such an environment empowers participants to embrace their full selves and contributes to the group’s collective growth. To illustrate, a participant poignantly stated, “thank you for contributing all that you all are to make this such an authentic and loving space, I feel so blessed when I’m here. I can bring all that I’m carrying and I don’t ever need to hold back or feel apologetic because I’m not the only one” [14]. A shared sense of vulnerability seemed to have been reciprocated among members.

Theme 4: Opportunity for Continued Identity Development

Another theme evident in the literature is the opportunity for continued identity development. Throughout the study, much of the literature alluded to affinity groups as providing a distinctive, intentional space where students and educators can engage in the organic exploration and development of their identities— an opportunity often unavailable in their daily lives. Unlike the structured demands of classrooms or workplaces, affinity groups encourage open-ended discussions and reflective practices, allowing participants to explore the complexities of their own identities. This environment nurtures the growth of intersecting identities, offering participants a platform to explore how race, gender, profession, and personal experiences shape their sense of self.

For students, these groups provide a space to unpack shared and conflicting experiences, fostering an understanding of collective identity, such as masculinity, while broadening perspectives. For educators, affinity groups create a “safe” space to connect their unique identities with their professional practices, empowering them to integrate these reflections into their teaching. Participants frequently reported feeling legitimized in their struggles and finding the freedom to “keep it real” about challenges, whether working with students of different backgrounds or navigating their own racial identity.

These spaces are particularly critical for those seeking to unlearn oppressive mindsets or to align their privileged positions with antiracist and equitable practices. By engaging in selfexploration and grappling with identity as a construct, participants are empowered to locate themselves within larger societal struggles, paving the way for collaboration and collective transformation.

Theme 5: Shifting of the Learning Environment

The idea of the “learning environment” came up multiple times throughout our review of the literature as affinity groups play a transformative role in reshaping learning environments by functioning as dual-purpose spaces for personal and professional growth. First, affinity groups serve as informal yet impactful learning environments. Some participants even compared their affinity groups to professional learning communities (PLCs). Teachers engaged in both structured and organic learning opportunities that deepened their understanding of their personal and professional identities. Through the development of genuine rapport and intentional dialogue, these spaces often act as a form of professional development, empowering teachers to explore critical issues like identity, equity, and classroom practices.

Second, participation in affinity groups enables teachers to make meaningful, critical changes in the learning environments they create for their students. By addressing the root causes of their own stress and burnout, teachers gain the tools to respond strategically to problematic behaviours and language, both within their classrooms and among colleagues. This process fosters professional self-efficacy, equipping teachers to leverage their unique identities and skills to lead from the classroom. Affinity groups also naturally became informal learning environments for students, creating spaces where they could engage in open discussions and explore shared experiences. These groups allowed students to navigate their identities collaboratively, gaining a sense of empowerment and validation. This organic environment encouraged students to take ownership of their own development, fostering critical thinking and deeper self-awareness.

Additionally, the shared space of affinity groups helps educators collect insights and data about their school environments, informing strategies to improve classroom dynamics and student engagement. Teachers learn to implement inclusive practices, transforming their classrooms into spaces that promote equity and empowerment. For Black teachers, in particular, these groups provide opportunities to heal, address systemic challenges, and gain the confidence to reshape the environments in which they work. Ultimately, affinity groups bridge the personal and professional, empowering educators to become change agents in their classrooms and beyond.

Theme 6: Taking a Stand

Collectively, many of these articles demonstrated either the

participants or the group facilitators “taking a stand” against

pressures within the educational environment, the community

or both. For instance, participants who participated in a Science

Fiction club that grew from 4 boys initially to the most active club

within the school highlights this idea that the group combatted

isolation and stereotypes about one’s identity which then led to

empowerment. Qualitative findings included:

“Being a part of a group that likes and encourages the same

interests as you give you somewhere and someone to turn to,” says

Kayleigh, a Sci-Fi Club member of the class of 2009. “If you are

ever bullied, then you have a safe place to go to where friends can

help stand up against a bully. Or even more importantly, because

there are people who have the same interests as you and you don’t

feel alone, your self-confidence is built up so you can stand up for

yourself.” [15].

In addition, these affinity spaces aimed to enhance group cohesion, particularly for groups that did not previously exist in the schools, and increase group comfort and support. In the quote above, victimization was reduced, and violence was potentially mitigated; therefore, taking a stand for oneself or others can transform school culture. To illustrate further, increasing relevant books in the library or painting a cafe mural symbolizes taking a stand and increasing school belonging, fighting injustices and isolation that stem from bullying.

Next, one affinity group used the name HELLA to capture the possibility of offering Healing, Empowerment, Love, Liberation, and Action using grassroots efforts [14]. Specific examples from this review included a follow up evaluation study whereby minoritized Muslim student voices, largely East African Muslim girls, were elevated, then dismissed by central school administration. However, after persisting and claiming their right to a “sociopolitical space in school” to pray and commune on a regular basis and receiving support from community supporters and advocates, their voices were finally truly heard and incorporated in decision making around affinity groups [16]. This indeed highlights inclusive excellence, because students created a space where, as word spread opposition emerged. However, after further resisting and using their collective voice to demand inclusion their religious needs were met.

Other salient examples of taking a stand include the empowerment, advancement and retention of Latinx teachers using affinity groups as a form of professional development.

Participants who attended this professional development, which embodied a training component and an affinity group component over several sessions, shared the following when asked what a transformative Latinx leader looks like in their school, “the majority of respondents referred back to equipping local communities with relevant resources to thrive, and many referenced their own empowerment projects that offered strategies along these lines. Specifically, the survey asked participants to summarize their projects and its impact. The projects included creating a club for Latinx students, establishing an engineering program for Latina high school girls, working with Latinx families to better understand college readiness for students, and creating “lunch bunch clubs” for Spanish-speaking students [17]. These empowerment projects are tangible examples of the positive influence participating school staff can have when they function as leaders who are empowered to take a stand.

Theme 7: Community in the Struggle

This theme shows up throughout the body of literature and

is espoused within affinity group discussions based on feedback

from staff and student participants. In one example where the staff

were the participants, a collective approach to education showed

up through reading, journal writings, and dinners that provided the

time for extended dialogues. When participants were asked about

the benefits of their sessions and what this actually means, one

member put it this way:

“This simply means that we aren’t just focusing on defining

our own anti-racist racial identities, but we are also focused on

presenting the group as an entity committed to fighting racism”

[14]. The sense of struggling with the community decreased their

feelings of isolation. In another example, Black male preservice

teachers who participated in the affinity group described being able

to “solve practice dilemmas collaboratively, learn from each other’s

experiences, and find validation in understanding that their schoolbased

challenges were shared by other members of the group” [18].

In addition to being in this struggle as a community, participation

offered tools to practice self-advocacy both for professional growth

and self-care.

For student participants, there were also a wide range of

experiences that demonstrated the power of the community and

engaging in resisting cultural mishaps and misunderstandings that

could lead to anxiety or fear. One author provided Testimonio and

storytelling to heal as a way to capture this evidence. For instance,

“As members shared their own stories, they ‘held space’ for

one another, which made the group a sacred space to learn. For

example, Jedaiah acknowledged, ‘I appreciate this space, not just for

the physical space but for how you all hold space and share space

with everyone here.’ [14].

To illustrate this community struggle and the benefits afforded, as students continued to participate, they grew more comfortable with their own voices. Students used their collective voice to cultivate a safe space, community empowering space, and a place of resistance while exploring the intersection of being Black and Muslim [16].

Theme 8: Critical Camaraderie [terminology first used in Pour-Khorsid’s study [14]]

Overall, there is an emphasis on collective healing within these articles. Many, but not all, of the participants (e.g., students or school staff) from this body of literature hold identities as people of colour. And even in cases when the participants do not hold these identities, there is dialogue within the affinity groups that includes race and culture which emerges in a manner that is full of camaraderie. The theme of critical camaraderie is evident in that the need for this connection came about in direct opposition or resistance to oppressive environments or the need to dismantle the status quo. For instance, Pour-Khorshid’s study explicitly centred 12 members’ voices, needs and collective knowledge to cultivate a humanizing and healing space and in turn help them navigate the socially toxic educational organization and coined the term “critical camaraderie” (2019, p. 324). In Tauriac et al., [6], participants received validation from peers to examine ideas with the group before presenting arguments to those outside of the group. This opportunity to engage fellow participants in a critical discourse on their various feelings of anger, pain or frustration helped to channel this into a productive expression that could be used to address the current fight they were engaged in. Shirazi [16] demonstrated that the groups allowed conversations centring well-being that was open-ended even though the underlying purpose for meeting was to provide a counter-space to express and explore what it means to be Black and Muslim within this particular school. The critical camaraderie was extended as participants continued to connect with one another once the meeting agenda items were finished. Time was spent socializing or designing materials for the Muslim Student Association. This affinity group was an outlet where participants could see themselves and others in a way that was collectively positive and affirming.

To illustrate how this theme of critical camaraderie was helpful in the affinity group that focused on whiteness, see Dorsal- Terminel, et al., [10]. The participants and researchers in this study worked collectively and in solidarity to reduce white saviourism, promote antiracist school practices, and to learn without harming people of colour. The space to have difficult conversations, express uncomfortable feelings, and promote cultural humility while developing one’s racial identity led to participants expressing that the group was a safe place to connect, explore, and process this development. The researchers/facilitators pointed out that the participants explicitly shared that the affinity group was an authentic, unfiltered, and safe space to ask questions and talk with others who might be able to understand the complexities associated with this form of internal learning and processing, particularly within the field of school counselling. This theme of critical camaraderie was less prevalent as a group leader; however, the group leaders were instrumental in creating a space for participants to benefit from these brave and honest interactions.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic literature review offer a comprehensive understanding of how affinity groups operate in school settings and the unique conditions they foster to promote inclusive excellence. Through the lens of power, privilege, and intersectionality (PPI), our analysis uncovered key factors that define the impact that the affinity groups we reviewed can have. These groups serve as spaces where individuals can experience a sense of belonging, empowerment, and community, while also navigating systemic inequities [6,7]. The emergent themes provide insight into the contributions that make affinity groups not only a viable option, but an essential modality for fostering equity and inclusion within schools.

While our initial intent was to explore how affinity groups promote inclusive excellence, our discourse analysis illuminated the underlying conditions and processes that facilitate group interactions that extend beyond what would typically be considered outcomes. In the present case, our shift in understanding offered an opportunity to focus on the process and the benefits. For instance, we found that affinity groups create a distinct psychosocial space, akin to bell hooks’ concept of homeplace—a site of refuge, healing, and empowerment within oppressive systems (hooks, 1990). This native land serves as the foundation from which all other group processes emerge. Without such a space, individuals may lack the psychological safety needed to engage in authentic dialogue, take a stand, or experience the full complexity of their identities, and move to discovery and self-awareness, which could be summed up as a set of outcomes. To better understand this process, affinity groups can be conceptualized as a dynamic, fluid progression rather than a rigid, linear structure. We created Figure 2 to illustrate this idea. For instance, Native land, or the creation of a safe and affirming space, serves as the entry point, fostering trust and connection. This foundation allows for deeper engagement, where participants can be celebrated as complex, experiencing affirmation for their multidimensional identities. Through this process, members develop the capacity for vulnerability without shame, which is critical for authentic self-expression and collective healing [14]. As participants grow within these groups, they begin to shift their learning environments, develop agency, and actively take a stand against systemic barriers. Ultimately, these spaces cultivate critical camaraderie, reinforcing the collective struggle for justice while empowering members to make meaningful changes ([16]. While this understanding is becoming clearer, it is imperative to be reminded that this is similar for groups facilitated in school settings in general - essentially the group itself is a process that leads to important and impactful outcomes across social-emotional, academic, career, and behavioural outcomes [19]. We also know specialized programs that draw upon the power of the group process including YPAR offer a process and powerful benefits [12]. That said, the current findings in this article provide a more compelling picture of the theoretical process demonstrating how affinity groups can be used to create inclusive excellence in educational settings.

Implications for Practice

The findings from this study underscore the importance of incorporating affinity groups in educational spaces. The process of affinity groups gleaned from our critical analysis indicates that affinity groups, while powerful spaces for connection, can lead to much broader outcomes transforming academic contexts into one of belonging and empowerment. To maximize their impact, facilitators must cultivate an environment where trust, psychological safety, and identity exploration are prioritized. Additionally, practitioners should consider the fluid nature of identity and allow participants to navigate their experiences with agency and self-determination. Moreover, affinity groups should not be viewed solely as intervention spaces but as proactive and integrated components of the school ecosystem. The success of affinity groups at the Tier 1 level of MTSS suggests that these groups can function as universal support structures, benefiting all students rather than being confined to those identified as needing additional support or seen from a deficit perspective (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins). Schools must shift from viewing group counselling programs in school settings and affinity groups in this particular case as reactive solutions to systemic inequities and instead recognize them as foundational to fostering inclusive excellence (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins).

Implications for Research

Despite the promising evidence supporting affinity groups, our review highlights the need for further empirical investigation into what dimensions of these groups are essential and if there is a longterm benefit beyond the life of the group. Future research could explore the sustainability of affinity groups and their influence on school-wide culture, student achievement, and educator retention. Additionally, more research is needed to understand the role of facilitators, including their training, positionality, and influence on group dynamics [10]. Given that some affinity groups in our review were led by various individuals other than school counsellors, understanding how different facilitators shape the group experience is crucial for informing best practices. Another important avenue for research is examining affinity groups across multidimensional contexts in schools. Most of the studies in our review focused on elementary and high school settings, with no clear example from middle schools. And, most of the studies included school staff. Specifically, 9 of the 10 articles with teachers as participants were noted during the years between 2015 and 2024. The other one was written in 2006. Put another way, from 2004 to 2015 seven articles had participants that were students. Future research could look more closely into what the trends that have occurred using a longer timeframe beginning before 2004 up to the present date and if there nuances that differentiate affinity groups with students versus school staff. Finally, our studies lacked various aspects across spectrums of identity for students and staff. For instance, one article had teacher participants from the Netherlands and one article had student participants described as immigrant children. Investigating how affinity groups function within an international context or for vulnerable youth could provide valuable insights into cultivating cohesive and impactful group spaces.

Implications for Policy

From a policy perspective, our findings suggest the need for more openness to the benefit that affinity groups offer beyond “evidence-based” or narrowly focused outcomes. For instance, facilitating groups that are responsive and less manualized more intentionally meets the needs of students in staff in their respective and current contexts. Next, another policy implication is the need for formal recognition of affinity groups within school counselling as a comprehensive service that offers value beyond the group setting and plays a larger role within a comprehensive developmental school counselling program. Revisit ASCA’s [1] position statement on group counselling, which acknowledges the benefits of group work, but does not explicitly state how groups can be used to meet the needs of all members of a school community (e.g., teachers, students and families), nor challenge systemic inequities (Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva, Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins). Furthermore, given the socio-political tensions surrounding race, identity, and education, policies must not hinder the integrity of affinity groups. School leaders and practitioners can demonstrate the purpose and benefits of these groups, emphasizing their role in fostering inclusion rather than division, if there is institutional guidance. Developing regulations for the implementation of affinity groups, including considerations for legal and ethical implications, privacy, participant autonomy, and facilitator training, are essential to ensuring their success and sustainability [17]. Finally, policymakers, district leaders, and counsellor educators should work to embed affinity groups within school structures, ensuring they are adequately resourced and supported rather than operating at the discretion of individual educators who may feel unprepared or unqualified.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this review provides a comprehensive analysis of affinity groups in schools, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the literature base remains relatively limited, with most studies focusing on specific populations or settings. As a result, our findings may not fully capture the diversity of experiences across different school contexts. One strength is that the studies reviewed varied in methodologies, however, only 3 of the articles used either quantitative strategies (n =1) or mixture of quantitative and qualitative strategies (n = 2). Future research should employ mixed methods approaches to deepen our understanding of affinity groups’ ability to attend to the unique needs of the school communities in which they are employed. In this case, determining impact might come from verbal feedback, written feedback or other modes of communication that may not typically be used to illustrate outcomes. This type of approach may require using a longitudinal approach whereby feedback from participants can be collected over time in order to examine students’ and educators’ experiences more fully. The variety of data collected over time could provide valuable insights into the lasting effects of these groups.

Conclusion

Following the implementation of the systematic literature review has in turn offered a theory of group counselling illustrated by the comprehensive look at affinity groups in educational settings. Groups are a powerful mechanism for fostering inclusive excellence in schools and affinity groups can be emphasized in this process. Providing a space where participants can experience belonging, affirmation, and empowerment, helps to mitigate systemic inequities and promote social-emotional well-being. Our review highlights the critical conditions that make affinity groups effective, offering a framework for their implementation and sustainability. Moving forward, it is essential for educators, researchers, and policymakers to recognize and support the role of affinity groups in transforming school cultures and advancing equity. As educational spaces continue to evolve, groups in school settings and affinity groups in particular, must not be seen as optional but as fundamental to creating places where all students and staff can thrive [20-34].

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Griffith C, Mariani M, McMahon HG, Zyromski B, Greenspan SB (2019) School counselling intervention research: A 10-year content analysis of ASCA-and ACA-affiliated journals. Professional School Counselling 23(1): 2156759X19878700.

- Berger C (2018) Bringing out the brilliance: A counselling intervention for underachieving students. Professional School Counselling 17(1): 86-96.

- Arendale DR, Hane AR (2014) Holistic growth of college peer study group participants: Prompting academic and personal development. Research and Teaching in Developmental Education 31(1): 7-29.

- Fitriasiwi AH, Pradana BA, Pramesthi H, Isbandi II, Makhmudah U (2022) Group Counselling Strategies to Overcome Problems in the Personal Social Sector for Junior High School Students: A Systematic Literature Review (SLR). In Social, Humanities, and Educational Studies (SHES): Conference Series 5(2): 356-369.

- Hoag MJ, Burlingame GM (1997) Evaluating the effectiveness of child and adolescent group treatment: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 26(3): 234-246.

- Tauriac JJ, Kim GS, Lambe Sariñana S, Tawa J, Kahn VD (2013) Utilizing affinity groups to enhance intergroup dialogue workshops for racially and ethnically diverse students. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work 38(3): 241-260.

- Kulkarni SS, Bland S, Gaeta JM (2022) From Support to Action: A Critical Affinity Group of Special Education Teachers of Color. Teacher Education & Special Education 45(1): 43-60.

- Welbourne TM, Rolf S, Schlachter S (2017) The case for employee resource groups: A review and social identity theory-based research agenda. Personnel Review 46(8): 1816-1834.

- Boston College Centre for Work & Family (2018) Employee resource groups: An effective strategy for advancing diversity and inclusion. Boston College Centre for Work & Family.

- Dosal-Terminel D, Kim Chang M, Carter H, Jiang AJ, et al. (2024) A Pilot Implementation of Affinity Groups for White School Counsellors and Its Impact on Antiracist Practice: The Experiences of Group Members. Professional School Counselling 28(1a): 2156759X241234905.

- Clayton-Pedersen A, Sonja CP (2007) Making excellence inclusive in education and beyond. Pepp. L. Rev 35: 611.

- Anyon Y, Bender K, Kennedy H, Dechants J (2018) A systematic review of youth participatory action research (YPAR) in the United States: Methodologies, youth outcomes, and future directions. Health Education & Behaviour 45(6): 865-878.

- White A, Schmidt K (2005) Systematic literature reviews. Complementary therapies in medicine 13(1): 54-60.

- Pour-Khorshid F (2018) Cultivating sacred spaces: a racial affinity group approach to support critical educators of colour, Teaching Education, 29(4): 318-329.

- Nurenberg D (2014) The Power of Positive Affinity Groups: A “Sci-Fi” Solution to Bullying. American Secondary Education 42(3): 5-17.

- Shirazi R (2018) “I’m supposed to feel like this is my home”: Testing terms of sociopolitical inclusion in an inner-ring suburban high school. Journal of Educational Administration 56(5): 519-532.

- Lichon K, Moreno I, Villamizar AM, Arana K (2022) Fortalecer raíces y formar alas: Empowerment, advancement, and retention of Latinx educators and leaders in Catholic schools. Journal of Catholic Education 25(2): 44-64.

- Mosely M (2018) The Black teacher project: How racial affinity professional development sustains Black teachers. The Urban Review 50(2): 267-283.

- Coogan T, Steen S (2022) Group counselling leadership skills for school counsellors: Stretching beyond interventions. Cognella Academic Publishing.

- Andersen BB (2015) Development of analytical competencies and professional identities through school-based learning in Denmark. International Review of Education 61: 761-778.

- Beasley JJ, Ieva KP, Steen, S (2023) Reclaiming the system: Group counselling landscape in schools. Professional School Counselling 27(1a).

- Beasley JJ, Ieva KP, Steen S (2024) Reimagining groups: A phenomenological investigation of affinity groups in schools. Professional School Counselling 28(1a).

- Boston College Centre for Work & Family (n.d.). From civil rights to corporate change: Xerox’s guide to employee resource groups.

- Bristol TJ, Wallace DJ, Manchanda S, Rodriguez A (2020) Supporting Black male preservice teachers: Evidence from an alternative teacher certification program. Peabody Journal of Education 95(5): 484-497.

- Denevi E, Pastan N (2006) Helping Whites develop anti-racist identities: overcoming their resistance to fighting racism. Multicultural Education 14(2): 70-73.

- Keddie A (2004) Research with young children: the use of an affinity group approach to explore the social dynamics of peer culture. British Journal of Sociology of Education 25(1): 35-51.

- Mason ECM, Dosal-Terminel D, Carter H, York Streitmatter S (2024) Affinity groups to build homeplace and cultural humility practices of white school counsellors. Theory Into Practice 63(1): 49-57.

- Oto R, Chikkatur A (2019) “We didn’t have to go through those barriers”: Culturally affirming learning in a high school affinity group. Journal of Social Studies Research 43(2): 145-157.

- Parsons J, Ridley K (2012) Identity, Affinity, Reality: Making the Case for Affinity Groups in Elementary School. Independent School 71(2).

- Steen S, Liu X, Shi Q, Rose J, Merino K (2018) Promoting school adjustment through group work: Implications for school counsellors. Professional School Counselling 21(1): 1-10.

- Steen S, Shi Q, Melfie J (2021) A systematic literature review of school-counsellor-led group counselling interventions targeting academic achievement: Implications for research and practice. Journal of School-Based Counselling Policy and Evaluation 3(1): 6-18.

- Steen S, Melfie J, Carro A, Shi Q (2022) A systematic literature review exploring achievement outcomes and therapeutic factors for group counselling interventions in schools. Professional school counselling 26(1a): 2156759X221086739.

- Souto-Manning M (2013) Competence as linguistic alignment: Linguistic diversities, affinity groups, and the politics of educational success. Linguistics and Education 24(3): 305-315.

- Young CD (2023) Seeking Common Ground: The Impacts of Racial Affinity Groups and Varsity Athletics on Sense of Belonging, Social Capital, and Identity Development in Independent Schools (Order No. 30636319). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2903211717).

-

Sam Steen*, Jordon Beasley, Kara Ieva Zikun Li and Lisa Atkins.Affinity Groups in Educational Settings to Promote Inclusive Excellence: A Systematic Literature Review. Iris J of Edu & Res. 5(5): 2025. IJER.MS.ID.000616.

-

Affinity groups, Small group counselling, School counselling, Inclusive excellence

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Language Representation in the Brain

- What are the Cognitive and Neural Consequence of Bilingualism?

- Developmental Changes across Lifespan in Bilingualism

- Neuroimaging Tools to Study Bilingualism

- Language Experience and Neuroplasticity

- Conclusion and Future Direction

- Acknowledgment

- Conflict of Interest

- References