Research Article

Research Article

Ophthalmic Manifestations in Female Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangladesh

Sharfuddim Ahmed*1, Tasruba Shahnaz2, Shams Mohammed Noman3 and Shawkat Kabir4

1Professor & Chairman, Department of Community Ophthalmology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh

2Resident (Phase B), Department of Community Ophthalmology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh

3 Senior consultant, Chittagong Eye Infirmary and Training Complex, Bangladesh

4 Associate professor, Department of Community Ophthalmology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh

Sharfuddim Ahmed, Professor & Chairman, Department of Community Ophthalmology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh.

Received Date: May 15, 2019; Published Date: May 22, 2019

Abstract

Introduction: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease, more common in women of childbearing age. Ocular manifestations of SLE are common and may lead to permanent blindness from the underlying disease or therapeutic side effects. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is the most common manifestation.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to determine the ocular manifestation of SLE and to evaluate the distribution of ophthalmic manifestations in SLE female patients.

Methods: This cross sectional, consecutive study investigated 84 female patients who were diagnosed case of SLE by the Rheumatologist in Department of Rheumatology, BSMMU. A complete clinical evaluation including relevant all ocular examinations was performed in the Community Ophthalmology department, BSMMU.

Results: In current study showed females were predominant in SLE. Estrogen, likely contributes to the development of lupus in women who are genetically susceptible. The mean age was found 34.5 ± 9.3 years. Overall, among the SLE female patients included in the current study, 42.84% (n=36) patients had ocular manifestations while 57.12% (n=48) of the patients did not develop ocular manifestations at the time of enrolment in present study.

Conclusion: Ocular affection is frequent in SLE patients. Dry eyes and retinopathy (especially cotton-wool spots) are the most common findings. Early recognition by the rheumatologist, prompt assessment by the ophthalmologist and coordinated treatment strategies are key to reducing the ocular morbidity associated with this disease.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by production of numerous antibodies that may affect multiple organ systems. 9 out of 10 adults with lupus are women and most women who develop lupus are between the ages of 15 and 44 [1]. Lupus is thought to develop due to an interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers. Previous studies have identified a number of genes referred to as “lupus susceptibility genes,” the presence of which are thought to increase the likelihood of developing lupus. This increased susceptibility may be made possible, at least in part, due to differences related to hormones and sex chromosomes. However, to what extent these sex differences contribute to the development of lupus is largely unknown. About one-third of patients suffering from SLE have ocular manifestations and also a marker for overall systemic disease activity [2]. SLE can affect the eye in a variety of ways. Findings may include abnormalities of the eyelid, ocular adnexa, keratoconjunctivitissicca, iridocyclitis, retinal vasculitis, vaso-occlusive disorder, choroidopathy and optic neuropathy. Keratoconjunctivitissicca (KCS) is the most common manifestation while retinal and choroidal involvements are most associated with visual loss [3]. The prevalence of KCS among patients with SLE is approximately 25% [4].

The incidence of retinal involvement in SLE is 7–26 %. It is one of the most common vision-threatening complications of SLE with an incidence of up to 29 % in patients with active systemic disease [5]. Orbital involvement is a rare manifestation of SLE. Typical lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus are slightly raised, scaly, and atrophic rarely affecting the eyelids. The incidence of SLE in patients with scleritis is about 1% (Sainz de la et al 1994). Episcleritis is generally a benign inflammation of the episclera and typically occurring in young females with incidence 2.4% in SLE [6]. Corneal epitheliopathy, scarring, ulceration and filamentary keratitis can be found secondary to keratoconjunctivitissicca. More rare corneal complications include peripheral ulcerative keratitis [7], which can be a marker of active systemic disease activity. The prevalence of SLE in patients with uveitis varies from 0.1% to 4.8%. Optic nerve involvement in patients with SLE may be in the form of optic neuritis, ischemic optic neuropathy and papilledema, and it occurs in around 1 % of SLE patients [8]. Lupus choroidopathy serves as a sensitive indicator of lupus activity. SLE retinopathy is believed to be an immune complex–mediated vasculopathy. In Bangladesh there is no broad-based study about ocular manifestations of SLE. In this study, a cross sectional study was done for the evaluation of ocular manifestations of SLE in Bangladeshi female patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted from March 2015 to August 2017 in Department of Community Ophthalmology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University and Department of Rheumatology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University among 84 female SLE patients. The consecutive sampling technique was applied to collect sample from the study population, as per inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria of case were age 15 years and above, female, patients diagnosed as a case of SLE on the basis of 1997 ACR criteria [9] and patients willing to participate in this study. Criteria for exclusion was patients with other systemic diseases that may produce eye pathology e.g. diabetes mellitus, pre-existing hypertension, known congenital ophthalmic disorder, history of any previous ocular trauma or surgery and history of any previous ocular pathology. Ocular manifestations were evaluated by the Ophthalmologist during the study period in the Department of Community Ophthalmology. Complete clinical evaluation including history, physical examination, laboratory investigations, relevant ocular examinations and systemic examinations was performed in the Community Ophthalmology department, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University.

Ocular examinations included best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), pupillary light reaction, RAPD, Hirschberg reflex, ocular motility, color vision, confrontation test, slit lamp examination of anterior segment and fundus examination with the help of +90 D condensing lens, direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy, Schirmer’s test, tear film break up time (TBUT), IOP measurement by Goldmann applanation tonometer and Cranial nerve examination. Following investigations were done for every patient-colour fundus photography (CFP), complete blood count (CBC), urine R/M/E and antiphospholipid antibody (APA). Assessment of SLE disease activity is depends upon flares which is closely associated with ophthalmic manifestations. Criteria for a mild/moderate and severe flares were developed for use in SELENA trial [10].

Informed consent: For this study, a well informed, voluntarily signed written consent had been taken in an understandable local language from the study subjects.

Confidentiality: All the research data were coded with special ID and stored in a locked cabinet. Only research personnel were allowed to access the data.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and presented as table and figure. A probability p value of 0.05 or less was considered as significant.

Results

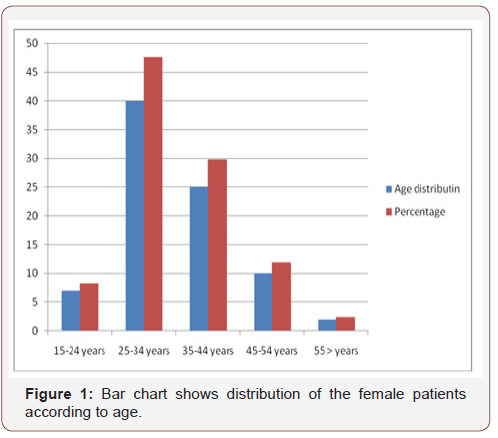

Distribution according to age: 84 female patients were enrolled. The mean age was found 34.5 ± 9.3 years. The age range of the patients were 15 years and above. The bar diagram below Figure 1 shows demographic variables of the study patients. It was observed that most of the patients belong to 25-34 years age groups was 40 (47.61%). Most uncommon in 55 and more age group (Figure 1).

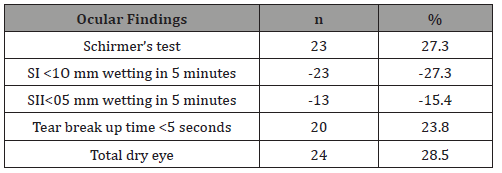

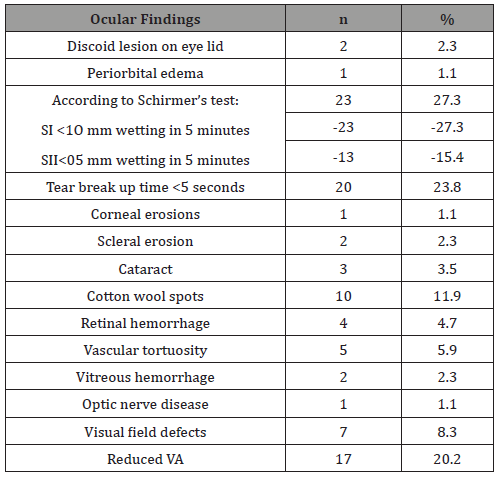

Frequency of the ocular manifestations and it’s patterns in female SLE patients: The study included 84 female SLE patients. Out of the 168 eyes of those 84 patients, 36 (42.84%) patients had ocular manifestations related to SLE disease. The frequency of variable patterns of ocular manifestations found in SLE patients enrolled in the present study are summarized in Table 1. The most common ocular manifestation was dry eye in 28.5% (according to Schirmer’s test & Tear break up time.

Table 1: Frequency of Dry eye in female SLE patients: (n=84).

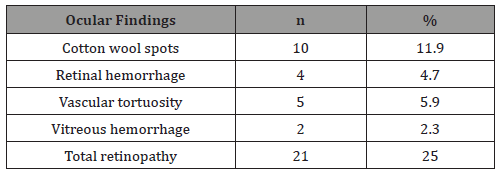

Other manifestations were: Retinopathy (25%), reduced visual acuity in 20%, visual field defect in 7%, scleritis, episcleritis& corneal lesion in 3%, each of the discoid lesion and the periorbital edema affected 2.3% and 1.1% respectively in three patients (3.57%) and cataract in 3% cases. Cotton-wool spots were the most common retinal abnormal finding followed by vasculitis, attenuated blood vessels, papilledema and pale optic disc was found 1.1% (Table 1,2 &3).

Table 2: Frequency of Retinopathy in female SLE patients: (n=84).

Table 3: Frequency of the ocular manifestations in female SLE patients: (n=84).

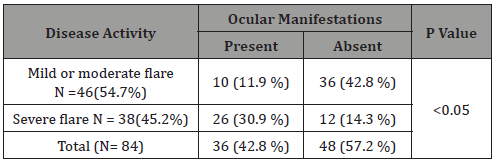

VA-Visual Acuity: Association of disease activity of female SLE patients on the basis of SELENA modification with ocular manifestations. Among the female SLE patients (N=84), mild to moderate flare was present in 46 (54.7%) patients and remained 38 (45.2%) patients had severe disease flare. Here 26 (30.9 %) patients of severe disease flare presented with ocular manifestations wherever, 10 (11.9 %) patients of mild to moderate disease flare presented with ocular manifestation. So, p value is <0.05 (Table 4).

Table 4: Association between disease activity of SLE and ocular manifestations (n= 84).

Discussion

SLE is a chronic inflammatory disease with multisystem involvement having different clinical and immunological manifestation characterized by the presence of antinuclear antibodies. Ushiyama et al. (2000), reported the mean age at the onset of SLE in the patients with and without ocular manifestations to be 34.2 and 31.9 years, respectively, and all of them were females. This is comparable with this study where the mean ages at onset of SLE in our patients were 34.5 ± 9.3 years. In current study showed females were predominant in SLE. Estrogen, likely contributes to the development of lupus in women who are genetically susceptible, published by Hughes in 2015. Overall, among the SLE patients included in the current study, 42.84% (n=36) patients had ocular manifestations while 57.12% (n=48) of the patients did not develop ocular manifestations at the time of enrolment in present study.

Previous studies by different researchers showed that eye involvement has been found in 20% to 47.3% of patients with SLE2,3,4. El-Shereef et al. 2013, enrolled 53 SLE patientsin his study. Ophthalmologic examination of the patients revealed that 18 patients (34.6%) had ocular involvement, from which only 13 (25%) patients were symptomatic. Silpa-Archa et al. 2015, reported that ocular manifestations are common in SLE however they did not state the rate of presence of ocular manifestations. Also, in agreement with the findings of the current study, previous study found that the majority of SLE patients do not develop ocular symptoms throughout the course of their illness [7]. In the present study, each of the discoid lesion and the periorbital edema affected 2.3% and 1.1% respectively in three patients (3.57%). In agreement with our findings, periorbital edema was an uncommon manifestation of SLE with an overall incidence ranging from of 0.1% to 4.8%. Discoid lesion in the eye lid is exceptionally rare in the course of SLE (Gupta et al. 2012), however, Pandhi et al. found that discoid lesion had affected only 6% of patients with SLE [11]. In the present study 24 (28.5%) patients had manifestation of dry eye. Dry eye syndrome was frequently reported in patients with SLE. Several studies found that dry eye is the commonest eye manifestation in SLE being affecting 36.7% [12], 39.5% [6] and 50% [13] of the patients. Klejnbergand Moraes found that the dry eye syndrome was diagnosed in 31.4% of the lupus patients [14].

Probably, dry eye is the most common complication in SLE. Because this disease interfere the natural tear production and chemical levels of the body, leading to drying out various parts of the body. In the present study, 3 patients (3.5%) had cataract. Alderaan et al. 2015 found that the prevalence of cataract among the patients after 4 years from onset of lupus was 5.2% which comes in agreement with our findings. In the present study, fundus examination of the patients had shown that 10 (11.9%) patients had cotton wool spots, 4 (4.7%) had retinal hemorrhage, 2 (2.3%) had vitreous hemorrhage. Fouad et al. 2015, stated that the retinopathy frequently seen in patients with SLE generally consists of cotton wool spots with or without retinal hemorrhages. Lupus retinopathy in the form cotton-wool spots, perivascular hard exudates, retinal hemorrhages has been found to affect 2.5% to 3.7% to 10% of the lupus patients [15].

The results of the current study also revealed that the SLEDAI score is significantly higher in SLE patients with ocular manifestations than those without ocular manifestations. In agreement with our results, Silpa-Archa et al. 2015, reported that ocular manifestations are common in SLE and presence of ocular symptoms is correlated to systemic disease activity.

Conclusion

Ocular affection is frequent in female SLE patients. Dry eyes and retinopathy (especially cotton-wool spots) are the most common findings. Anti-phospholipids, lupus renal manifestations and active disease are significantly related to eye affection especially retinopathy among female SLE patients. In the most active time of a female is her child-bearing age, which is most commonly affected by SLE and its debilitating ocular manifestations. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment can give these women a light of hope.

Recommendation

From the finding of this study we recommend to carry out longer and larger multi-centric prospective studies.

Further studies are necessary to see the long term ophthalmic manifestations in patients with SLE and follow up of those patients which may be beneficial to improve their ophthalmic & overall conditions and for a better management. Early recognition by the rheumatologist, prompt assessment by the ophthalmologist and coordinated treatment strategies are key to reducing the ocular morbidity associated with this disease.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No Conflicts of interest.

References

- Patel P, Werth V (2002) Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a review. Dermatol Clin 20(3): 373-385.

- Palejwala NV, Walia HS, Yeh S (2012) Ocular manifestations of systemic lupus. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 12: 87-99.

- Silpa archa S, Lee JJ, Foster CS (2016) Ocular manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Br. J. Ophthalmol 100(1): 135-141.

- Read RW (2004) Clinical mini-review: systemic lupus erythematosus and the Eye. Ocular Immunology & Inflammation 12(2): 87-99.

- Sobrin L, Foster CS (1994) Systemic lupus erythematosus choroidopathy. British medical journal.

- Sitaula R, Shah DN, Singh D (2011) The spectrum of ocular involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus in a tertiary eye care center in Nepal. Ocular Immunology & Inflammation 19(6): 422-425.

- Messmer EM, Foster CS (1999) Vasculitic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Survey of Ophthalmology 43 (5): 379-396.

- Sheraj J, Niţescu D (2012) Ocular manifestations of connective tissue disease. Revista Română De Reumatologie 21: 214-217.

- Yu C, Gershwin ME, Chang C (2014) Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical review. J Autoimmun 48-49: 10-13.

- Petri M, Hellmann D, Hochbert MC (1992) Validity and reliability of lupus activity measures in the routine clinic setting. Journal of Rheumatology 19(1): 53-59.

- Pandhi D, Singal A, Rohtagi J (2006) Eyelid involvement in disseminated chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 72(5): 370-372.

- Mendes LE, Gonçalves JOR, Costa VP (1998) Ocular alterations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arq Bras Oftalmol 61(6): 713-716.

- Davies JB, Rao PK (2008) Ocular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 19(6): 512-518.

- Klejnberg T, Moraes Junior HV (2006) Ophthalmological alterations in outpatients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arq Bras Oftalmol 69 (2): 233-237.

- Ohsie LH, Murchison AP, Wojno TH (2012) Lupus erythematosusprofundus masquerading as idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome. Orbit 31(3): 181-183.

-

Sharfuddim Ahmed, Tasruba Shahnaz, Shams Mohammed Noman and Shawkat Kabir. Ophthalmic Manifestations in Female Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangladesh. W J Opthalmol & Vision Res. 2(1): 2019. WJOVR.MS.ID.000528.

-

Ophthalmic manifestations, Lupus erythematosus patients, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Childbearing age, Rheumatologist, Genetic susceptibility, Environmental triggers, lupus susceptibility genes, Sex chromosomes, Eyelid, Ocular adnexa, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, Iridocyclitis, Retinal vasculitis, Vaso-occlusive disorder, Choroidopathy, Optic neuropathy.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.