Research Article

Research Article

Effectiveness of Mindfulness Strategy to Promote Cultural Awareness Among Undergraduate Nursing Students in Egypt and the United States

Audrey Tolouian1*, Naglaa El Mokadem2, Melissa Wholeben1, Sarah Yvonne Jimenez1 and Diane Rankin2

1Department of Nursing, University of Texas at El Paso, United States

2Department of Nursing, Menoufia University, Cairo, Egypt

Audrey Tolouian, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 W University Ave, El Paso, Texas 79902, United States of America.

Received Date:December 20, 2022; Published Date:January 11, 2023

Abstract

Nursing students across the globe have committed themselves to one of the most demanding courses of study as they prepare for professional practice. The stress associated with nursing school was amplified with the isolation and uncertainty brought on by worldwide quarantines during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this project was to implement a virtual international exchange program titled “the Coffee Shop” to determine its effectiveness as a strategy to promote cultural awareness, increase cultural empathy, and enhance self-care through mindfulness among nursing students enrolled in undergraduate nursing programs in Egypt and the United States in 2020. Students’ cultural mindfulness and cultural empathy levels were assessed before and after the initiation of a series of virtual sessions that incorporated mindfulness activities. Forums were included to promote cross-cultural dialogue. Due to the universities closing for Covid-19, there was an insufficient number of surveys completed at the end of the sessions to allow for meaningful comparison studies. Informal student feedback at program completion indicated satisfaction with this virtual international mindfulness exchange. Further investigation is needed to determine if incorporating mindfulness education in an international virtual exchange program enhances cultural empathy and bolsters students’ self-care skills to manage stress.

Opinion

Nursing has been recognized as one of the most stressful professions worldwide. The journey to becoming a nurse is rigorous and fraught with innumerable stressors as nursing students balance personal lives with the demands of the didactic and clinical components of nursing school. The emergence of COVID-19 has compounded the difficulty of navigating nursing programs as quarantines made it necessary to deliver courses in virtual settings at the onset of the pandemic. The arduous adjustments made by faculty and students alike to operate in an online environment were made more challenging by the psychological impact that isolation and the profound uncertainty of health, well-being, and survival have had on nursing students throughout the globe.

Despite these unprecedented challenges to nursing education, faculty have been tasked to maintain nursing programs’ quality and standards and provide nursing students with tools that promote their mental well-being. Many collegiate and professional nursing organizations have advocated for educating students about the importance of self-care and have called for incorporating selfcare activities in nursing curriculums [1,2]. The intent is that students will carry this knowledge and use these skills to manage the stressors they will face in their future professional lives. Rising rates of nurse burnout, anxiety, depression, and suicide, coupled with high turnover rates that threaten the maintenance of a robust nursing workforce and, consequently, patient safety, have made it imperative to provide students with the resources necessary to thrive in health care environments [3]. The American Academy of Nursing (AACN) has made self-care, holistic care, and cultural competency part of The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education that will govern curricula [2]. Therefore, nurse educators must search for strategies that build these competencies.

Nursing students must expand their cultural knowledge as communities become increasingly diverse. Cultural competence is a crucial tenet of nursing, and nurse educators work to find opportunities to broaden internationalization to prepare nursing students to provide culturally appropriate care. Global health education is a critical component in baccalaureate nursing education and is recognized by organizations that accredit nursing programs to prepare nurses to provide culturally competent, highquality care [1,2,4].

At one of the heights of the global pandemic, during the fall of 2020, two universities in the United States and Egypt had the opportunity to facilitate a virtual exchange program under the guidance of the Texas International Education Consortium (TIEC) and the Stevens Initiative [5]. TIEC and the Stevens Initiative collaboration aims to build bridges between cultures. The confluence of students worldwide engaging in virtual studies and living through a global pandemic presented a rich opportunity to unite and share ideas for alleviating the stress brought on during this unrivaled time in history.

Background/Literature Review

The college years are a challenging developmental period that may affect students’ well-being later in life as they experience stress and other psychological troubles. Untreated mental disorders influence academic success, productivity, substance use, and social relationships [6,7]. Psychological disorders and stressrelated problems are highly prevalent among college students and have been progressively increasing in prevalence and severity over time [8]. Social isolation, anxiety, and depression have increased remarkably among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic [9].

In addition, college students confront many problems in their studies, such as maintaining concentration, remembering details, and meeting deadlines under pressure [10]. These problems may lead to adverse educational effects and eventual dropout from college [11]. Nursing students have reported higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression than other university students or working adults in the same age group [12]. In addition, nursing students have described their nursing education as stressful, especially time spent in clinical training [13-16].

Recently, mindfulness has become incorporated into several well-known mental health interventions because of its reported positive effects on human health and well-being and capacity to reduce a range of stress-related physical and psychological problems [17,18]. Mindfulness techniques have been shown to decrease the stress and anxiety of nursing students [19-22].

Significance of Project

Undergraduate nursing students are at a higher risk for experiencing stress and anxiety compared to students from other programs. Stress and anxiety in nursing students have been reported as a cross-cultural phenomenon that can have a profound negative impact on the student’s physical and psychological health as well as academic performance, highlighting the international scope and importance of this issue [23]. A mindfulness intervention is an acceptable, effective, cost-effective, and implementable intervention that may provide a multidimensional solution to nursing students’ physical and mental health problems. Mindfulness is a non-pharmaceutical therapeutic without the side effects associated with the use of anti-anxiety and antidepressant medications. It has been suggested that mindfulness interventions could be used as a preventative college health intervention. It is important to assess student knowledge regarding mindfulness. Students from various backgrounds may perceive and value mindfulness-based interventions differently. Therefore, nurse educators must understand students’ perceptions and values to tailor appropriate interventions and improve student well-being and academic performance.

Stress, anxiety, and depression rates have doubled among college students over the last two decades [24,25]. A mindfulness intervention is an inexpensive and effective intervention that may provide a multidimensional solution to nursing students’ physical and mental health problems. Mindfulness is a non-pharmaceutical therapeutic without the side effects associated with the use of anti-anxiety and antidepressant medications [26,27]. It has been suggested that mindfulness interventions could be used as a preventative college health intervention. It is important to assess student knowledge regarding mindfulness. Students from various backgrounds may perceive and value mindfulnessbased interventions differently. Therefore, nurse educators must understand students’ perceptions and values to tailor appropriate interventions and improve student well-being and academic performance.

One of the aims of this project was to increase cultural awareness and cultural empathy among undergraduate nursing students in Egypt and the United States. The second aim of this project was to obtain baseline information to examine the effects of a series of mindfulness-based interventions on reducing stress among American and Egyptian undergraduate nursing students.

The third aim of this project was to explore similarities and differences in perceptions of mindfulness-based interventions among the students before initiation of the virtual exchange program and after its completion.

The first step of this pilot project was to implement a virtual international exchange program to determine its effectiveness as a virtual teaching strategy to promote cultural awareness and empathy while enhancing mindfulness as a self-care strategy among nursing students enrolled in undergraduate nursing programs in Egypt and the United States. Consideration was given to the possibility that a mindfulness technique, such as meditation, may be practiced differently by students from Western cultures and Middle Eastern cultures, and may be viewed differently by students from various faith communities.

Theoretical Framework

There is no reported theoretical framework that links mindfulness to stressors and stress reduction. However, it was suggested that Modeling and Role Modeling (MRM) nursing theory [28], could provide a foundation. Therefore, the current study used the Modeling and Role-Modeling nursing theory to guide the study and to describe the linkages between (MRM) nursing theory and mindfulness. The theory of Modeling and Role Modeling explains the concepts relevant to human nature, person and health. One of the key concepts in the theory is self-care. In MRM, self-care is the ability to care for oneself to promote health by meeting basic human needs, including those that facilitate growth and development throughout one’s lifetime. Every person can care for themselves on some level, but specific self-care is unique to each individual. Because each person has a unique view of the world, a self-care approach that works for one person might not work for another. The concept of self-care can be further delineated into self-care knowledge, resources, and actions. These concepts, as applied to mindfulness training for nursing students, inform that self-care knowledge is the awareness of the amount of stress and need for mindfulness training. Self-care resources are the ability to participate in mindfulness classes and self-care actions are the implementation the mindfulness techniques.

Project

This pilot project involved two groups of undergraduate nursing students. One group was enrolled in a nursing research course from a regional university in Egypt, and the other group was enrolled in a nurse research course from a public university in the United States. Approximately 470 students participated in seven virtual sessions in which mindfulness or other self-care topics were presented and discussed throughout one semester.

Ethical Considerations

This project and pilot study was conducted according to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The University of Texas at El Paso Institutional Review Board approved the study. After the project and anticipated study were explained including risks and benefits, students who wished to participate in the project and pilot study gave their consent. Student identities were kept confidential to ensure privacy.

Methods and Design

Nursing students from both universities aged eighteen years and older completed a demographic survey about stress-relieving strategies. They answered questions on the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) and the Global Competency Empathy Survey before and after completing the virtual “Coffee Shop” series [29,30]. An informative descriptive study was used to inform activities for future course development. Sample demographic characteristics were assessed, self-care activities were selected based on this information, and informal feedback was obtained that guided the development of a subsequent study conducted the following semester.

Stress-reduction activities and mindfulness activities were shared with the students throughout the sessions. Each session featured a specific self-care topic. The students were taught abdominal and pranayama breathing techniques. They participated in a guided meditation, spent time in nature, and reflected on the experience. They brought their pets to “virtual” class, colored mandalas, and learned simple Tai Chi. The activities were taught in real-time by certified practitioners using a virtual video platform. The students joined the webinar from their homes, met as a large group to learn the activity, practiced the movement, and then met in small breakout groups to discuss their insights of the activities with their international counterparts. During the small groups, the students were encouraged to familiarize themselves with facets of their international colleagues’ cultures, ask questions, and were encouraged to dialogue with their international colleagues.

Description of Instruments

At the start of the semester, all participants completed surveys. Four categories of questions were asked: (1) basic demographics, (2) cultural sensitivity, (3) stress-relieving strategies, and (4) mindfulness attentive awareness scale (MAAS) scores. The demographic questions inquired about the respondent’s gender, age, ethnic origin, marital status, and travel. The cultural sensitivity prompts asked questions regarding the spoken language, media, and cultural background. The third set of question prompts centered on stress-relieving practices that participants had utilized previously. Finally, a category of questions relating to the MAAS survey was included. This 15-item scale was developed to examine a critical aspect of dispositional mindfulness and present-oriented awareness [31].

Results

Participant Demographics

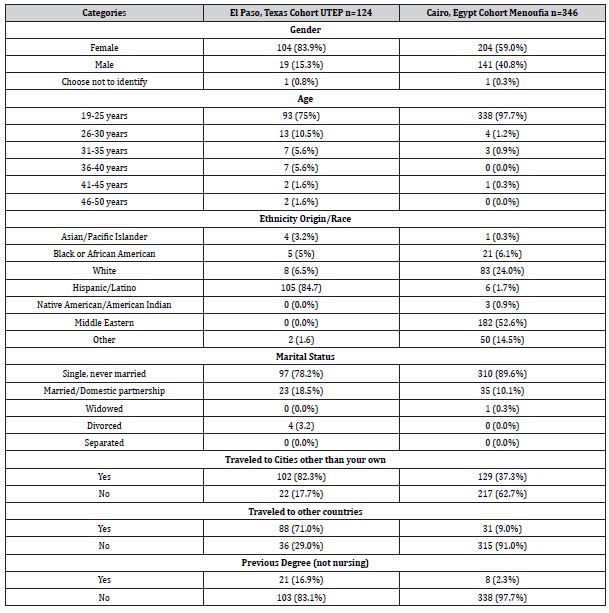

A total of 470 student participants completed the Coffee Shop activity. There were 124 student participants from the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) in El Paso, Texas. This group consisted of students enrolled in the second year of courses of their nursing program. The 346 participants from Menoufia University in Cairo, Egypt, were enrolled in Fourth Level of Nursing Research class.

The UTEP population was diversified in age, race/ethnicity, and history of travel outside of their region. The bulk of those who took part were female (83.9 %). The participants’ ages ranged from 19 to over 50 years. The majority were single or never married (78.2 %). Hispanic/Latino participants made up the bulk of the participants (84.7%). The most significant number of participants (82.3% and 71.0%) said they had gone to cities outside of their hometown and foreign countries, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic Results of Participants.

The Menoufia population was mainly under the age of 25 (97.7%), with a predominance of female nursing students (59.0 %). Middle Eastern (52.6%) was the most often identified ethnicity, with White coming in second (24.0 %). Like the UTEP participants, the majority of Menoufia participants listed their marital status as Single/Never Married (89.6%). Concerning travel, the majority of Menoufia students indicated they had not visited other cities (62.7%) or countries (91.0%)

Cultural Empathy

Four cultural empathy prompts were given to all participants. Attitudes toward language, stereotypes, interaction, and judgment were all addressed in the questions. Participants were asked to express their thoughts on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. The majority of participants indicated the Disagree response when asked if they felt irritated with a different language being spoken around them (UTEP 91.1%, Menoufia 57.5%), and if they felt impatient when interacting with people from other countries (UTEP 93.6%, Menoufia 61%). The response ‘Agree’ was the most significant percentage when asked if it bothers them with media portrayals of people based on cultural stereotypes (UTEP 75%, Menoufia 35.8%), and if they get disturbed when people are judged on their cultural background (UTEP 86.3%, Menoufia 48.9%)

Strategies to cope with stress

Participants were provided with a list of ten strategies that can be used to cope with stress. The top three strategies chosen by the UTEP participants were Exercise (68.5%), Pray (52.5%), and Breathing Practices (46.8%). For the Menoufia participants, the top three strategies were Pray (69.4%), Reading the Koran (52.3%), and Exercise (30.9%)

MAAS Survey (Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale)

All participants were asked to complete the MAAS survey before participating in the Coffee Shop activities. This survey asked 15 questions related to attention and awareness of their surroundings. The scores were tabulated and ranged from 15 (lowest) to 90 (highest). For the UTEP cohort, the highest percentages fell in the 34-52 range (31.5%) and the 53-71 range (40.3%). The results were similar for the Menoufia cohort, with 53-71 (49.7%) being the highest percentage.

Informal Student Feedback

The students learned about self-care tools, or self-care strategies and used them appropriately. Many students called and emailed their appreciation for the collaborative activities. The students were very positive in their unofficial reports of the activities.

• “I thought this was going to be a waste of time, but I learned so much and I looked forward to it each week!”

• ” I never would have made it through the semester without this”

• “These skills are so valuable for my life as a nurse”

• “I felt like I was really able to connect with my classmates and learn about them”

• “I shared these with my family members and we had fun being mindful together”

One of the unexpected outcomes of the program was that students exchanged their phone numbers and emails to stay in touch after the project and continue to be in contact. The faculty also built friendships and remained in contact as well.

Limitations

The study’s major limitation was that both universities closed during the final stage of the activity. We were unable to complete a full data analysis due to a lack of responses to the post-survey. We did analyze the demographic and MAAS survey comparisons, but the results were limited, though informal student feedback was extremely positive. Another limitation was the use of a virtual platform that did not allow us to include a large number of participants in a single session. Because the virtual platform would not allow us to have more than 400 participants, the facilitators had to run each session twice. Furthermore, the overall session size had to be kept under 200 people in order to use the breakout rooms for small group activities. Another limitation was the time zone difference during the holiday season. Due to seasonal obligations, many students were unable to attend the sessions until late in the day, which may have influenced their participation.

Discussion

This pilot project aimed to identify and create mindfulness activities suitable for two different cultures based on a cultural sensitivity survey and the MAAS survey. Currently, there were no other studies found concerning virtual international exchange programs that address mindfulness in the literature. It was amazing that the stress relief activities that students were using prior to the study, were very similar. The students reported prayer, going out into nature, and reading religious works as techniques they have used in the past. A project revealed that the students also had very similar stressors. School and illness ranked very high among concerns expressed by Egyptian and American students.

By teaching mindfulness techniques, nurse educators support the whole nurse and fortify the nurse in their role as a health care provider who can view themselves holistically and engage in selfcare effectively. Nurses must learn to exist in a state of continuous self-healing to keep the levels of burnout to a minimum, and nurses do this by becoming more mindful and more aware of themselves as both people and caregivers. By choosing culturally sensitive mindfulness techniques, we apply our understanding of the social and cultural issues that influence nursing [32].

Implications for Holistic Practice and Research

Graduate nurses report that stress related to work is the number one reason they leave the profession [33]. Most nursing school curricula often do not include mindfulness practices in their curriculum [34,35]. Students should acquire mindfulness skills to better prepare for the environment where they will find themselves. Mindfulness training has been linked to inquisitive minds, enhanced inter-relationships between self and patient, higher involvement, improved error awareness, and improved clinical insight [36]. Mindfulness programs have been shown to raise job satisfaction, reduce the amount of overtime required to perform daily activities, and reduce burnout, leading to lower attrition, greater quality, and improved patient safety results. [37].

Self-care and wellness activities are part of the nursing tool kit and are mandated by the ANA Code of Ethics fifth provision [38]. Nurses can internally build up their empathy and compassion during stressful events and promote safety and higher-quality patient care by performing self-care actions. In addition, specific programs, such as the MBSR interventions, have had positive results with new nurses, and it is recommended that administrators institute mindfulness into the academic curriculum and work facilities [39].

Conclusion

Our job as nurse educators is to develop and implement culturally sensitive mechanisms that the students can use to deal with their stress appropriately and create an environment that supports learning, understanding, and compassion for the student nurses. We also need to educate and offer tools for the students to reduce their anxiety by being a role model, understanding causal factors, and creating supportive environments to allow students to deal with stress with positive feelings.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Table 1: Distribution of ever-married females by age group and gravida and para, Kampung Peninjau Lama, December 2013.

- (2008) The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), Pp: 1-63.

- (2021) The Essentials: Core competencies for professional nursing education. American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). Pp: 1-82.

- Rebecca J Jarden, Aaron Jarden, Tracey J Weiland, Glenn Taylor, Helena Bujalka, et al. (2021) New graduate nurse wellbeing, work wellbeing and mental health: A quantitative systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 121: 103997.

- Wihlborg M, Friberg EE, Rose KM, Eastham L (2018) Facilitating learning through an international virtual collaborative practice. A case study. Nurse Educ Today 61: 3-8.

- Stevens Initiative (2020) Evaluating virtual exchange: Appendix: Common survey items for virtual exchange programs. Pp: 1-15.

- Hunt J, Eisenberg D (2010) Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J Adolesc Health 46(1): 3-10.

- Urban RW, Smith JG, Wilson ST, Cipher DJ (2021) Relationships among stress, resilience, and incivility in undergraduate nursing students and faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic: Policy implications for nurse leaders. J Prof Nurs 37(6): 1063-1070.

- Gallagher P (2014) National survey of college counseling centers, 2013, section one: 4-year directors. Project Report. The International Association of Counseling Services (IACS).

- Gopalan M, Linden-Carmichael A, Lanza S (2022) College students’ sense of belonging and mental health amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health 70(2): 228-233.

- Mowbray C, Megivern D, Mandiberg JM, Strauss S, Stein CH, et al. (2006) Campus mental health services: Recommendations for change. Am J Orthopsychiatry 76(2): 226-237.

- Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE (1995) Social consequences of psychiatric disorders I: Educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry 152(7): 1026-1032.

- Chernomas W, Shapiro C (2013) Stress, depression, and anxiety among undergraduate nursing students. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 10(1): 255-266.

- Moridi G, Khaledi S, Valiee S (2014) Clinical training stress-inducing factors from the students’ viewpoint: A questionnaire-based study. Nurse Educ Pract 14(2): 160-163.

- Sakallari E, Psychogiou M, Georgiou A, Papanidi M, Vlachou V, et al. (2018) Exploring religiosity, self-esteem, stress, and depression among students of a Cypriot University. J Relig Health 57(1): 136-145.

- Watson R, Deary I, Thompson D, Li G (2008) A study of stress and burnout nursing students in Hong Kong: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 45(10): 1534-1542.

- Zyga S (2013) Stress in nursing students. International Journal of Caring Sciences 6(1): 1-2.

- Hofmann SG, Sawyet AT, Witt AA, & Oh D (2010) The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 78(2): 169-183.

- Shapiro SL, Carlson LE (2009) The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions. American Psychological Association.

- Bamber MD, Morpeth E (2019) Effects of mindfulness meditation on college student anxiety: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 10(2): 203-214.

- Bamber MD, Schneider JK (2020) College students’ perceptions of mindfulness-based interventions: A narrative review of the qualitative research. Current Psychology 41(1–2): 667-680.

- Demarzo MMP, Andreoni S, Sanches N, Perez S, Fortes S, et al. (2014) Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in perceived stress and quality of life: An open, uncontrolled study in a Brazilian healthy sample. Explore (NY) 10(2): 118-120.

- Kabbat-Zinn J (2005) Full of catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Bantam Books.

- Gebhart V, Buchberger W, Klotz I, Neururer S, Rungg C, et al. (2020) Distraction-focused interventions on examination stress in nursing students: Effects on psychological stress and biomarker levels. A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract 26(1): e12788.

- (2014) ACHA-National College Health Assessment: Spring 2014, Reference group executive summary. Pp: 1-20.

- Black Thomas LM (2022) Stress and depression in undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Nursing students compared to undergraduate students in non-nursing majors. J Prof Nurs 38: 89-96.

- Townsend M (2015) Psychiatric mental health nursing 8th

- Jenkins EK, Slemon A, O’Flynn-Magee K, Mahy J (2019) Exploring the implications of a self-care assignment to foster undergraduate nursing student mental health: Findings from a survey research study. Nurse Educ Today 81: 13-18.

- Erickson H, Tomlin E, Swain MA (1983) Modeling and role-Modeling: A theory and paradigm for nursing. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, United States.

- Tolouian A, Wholeben M, Rankin D (2022) Teaching mindfulness to mitigate burnout in a pandemic. J Trauma Nurs 29(1): 51-54.

- Tolouian AC (2020) Taking time to enjoy some coffee! Adding mindfulness to the curriculum. Online Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine 5(1): 1-3.

- Brown KW, West AM, Loverich TM, Biegel GM (2011) Assessing adolescent mindfulness: Validation of an adapted mindful attention awareness scale in adolescent normative and psychiatric populations. Psychol Assess 23(4): 1023-1033.

- (2008) Cultural competency in baccalaureate nursing education. American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN).

- Crismon D, Mansfield KJ, Hiatt SO, Christensen SS, Cloyes KG (2021) COVID-19 pandemic impact on experiences and perceptions of nurse graduates. J Prof Nurs 37(5): 857-865.

- Carlson LE, Brown KW (2005) Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. J Psychosom Res 58(1): 29-33.

- Kachaturoff M, Caboral-Stevens M, Gee M, Lan VM (2020) Effects of peer-mentoring on stress and anxiety levels of undergraduate nursing students: An integrative review. Journal of Professional Nursing 36(4): 223-228.

- Laidlaw A, McLellan J, Ozakinci G (2016) Understanding undergraduate students’ perceptions of mental health, mental well-being and help-seeking behavior. Studies in Higher Education 41(12): 2156-2168.

- Burgstahler MS, Stenson MC (2020) Effects of guided mindfulness meditation on anxiety and stress in a pre-healthcare college student population: A pilot study. J Am Coll Health 68(6): 666-672.

- Dossey BM, Keegan L (2016) Nursing: Holistic, integral, and integrative-local to global. In: Dossey BM & Keegan L (Eds.) Holistic nursing: A handbook for practice. 7th Jones & Bartlett, pp. 3-52.

- Marthiensen R, Sedgwick M, Crowder R (2019) Effects of a brief mindfulness intervention on after-degree nursing student stress. J Nurs Educ 58(3): 165-168.

-

Audrey Tolouian*, Naglaa El Mokadem, Melissa Wholeben, Sarah Yvonne Jimenez and Diane Rankin. Effectiveness of Mindfulness Strategy to Promote Cultural Awareness Among Undergraduate Nursing Students in Egypt and the United States. On J Complement & Alt Med. 8(2): 2023. OJCAM.MS.ID.000682.

-

Complementary medicine; Alternative medicine; Mindfulness Strategy; Nursing Students; Cultural Awareness; Nursing curriculums; Anxiety; Depression; Suicide; Nursing Education; Nurse educators; Psychological disorders; Mental disorders

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.