Research Article

Research Article

The Efficacy of Choice Theory to Identify At-Risk Gambling Behavior in College Students

Tracy Poe* and Beth Vincent

Campbell University Buies Creek, North Carolina, USA

Tracy Poe, Campbell University Buies Creek, North Carolina, USA.

Received Date:February 14, 2019; Published Date: March 13, 2019

Abstract

Researchers agree that the age of onset of gambling is a predictor of future gambling problems [1-3]. Because other theories have failed to identify the internal drivers of problem gambling behavior among college students, Choice Theory was used to determine if the need for control or the need for achievement can predict at-risk problem gambling among the target population. The assessment tools/questionnaires used: (a) Demographic Information; (b) The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS); (c) Desirability of Control Scale; and (d) The Gambling Motivation Scale. The SOGS was utilized to determine a classification for being at-risk of developing gambling disorder. Results from an independent samples t-test indicated that there was not a significant relationship between the classification status of being at-risk of developing gambling disorder and need for control among college students. However, results from an independent samples t-test indicated that there was a significant relationship between the classification status of being atrisk of developing gambling disorder and need for achievement among college students. Of the college students who participated in this study, 21.22% met the criteria for being considered at risk of developing gambling disorder, which is comparable to a previous study reporting 17% of college students meet the criteria for gambling disorder [4]. This rate of prevalence of students at-risk in the sample reaffirms the need for ongoing support and intervention for gambling disorder prevention and interventions with young adults in the college setting.

Introduction

Gambling is defined as “risking something of value with the anticipation of gaining something of more value” American Psychiatric Association [5] and is a behavioral condition which does not involve ingesting substances.

According to Glasser W [6], behavior is intentional, purposeful, and based on choices. Thus, gambling is purposeful behavior. While there are physiological tests for ingesting substances, researchers and clinicians must rely on the individual’s self-report or observations of gambling behavior.

Different populations are impacted differently by gambling; specific to the proposed study are college students who are atrisk of developing a gambling disorder. According to the (NCRG) [7], 75% of college students reported past year gambling and 18% reported gambling on a weekly basis. As a result, 17% of college students meet the criteria for gambling disorders compared to only 5.5% of the adult population in the United States [4]. Consequently, college gambling has become an important public health concern [7]. Indeed, recent research has indicated that young adults experience more gambling-related problems than any other group Derevensky J et al. [8], highlighting the need for interventions for this vulnerable population [9].

Internal drivers are universal needs that individuals are motivated to meet for the purpose of survival [10]. According to Ashley and Boehlke [11], the pathological attachment is a compulsive attraction to a behavioral addiction that results in the individual being unable to resist the drive to engage in the behavior. Therefore, given the progressive nature of disordered gambling American Psychiatric Association [5], it is important to identify the internal drivers of problematic gambling so as to identify at-risk individuals early on.

According to Glasser W [6], there are four universal needs that humans are motivated to meet: (a) control; (b) power; (c) achievement; and (d) intimacy and that individuals engage in behaviors to satisfy these psychological needs. Unmet needs are processed as urgent, must be satisfied and because they must be met on a continual basis, there is no respite from satisfying these needs [6]. In Glasser W [12], Glasser developed Choice Theory because the behavior is a choice, and people make choices to meet their psychological needs. These choices manifest as maladaptive behavior when needs are unfulfilled [12]. Choice Theory is an effective addiction recovery tool because the individual must choose to stop abusing the substance, and this is a common variable for addictive disorders including drugs and gambling [13].

The problem is that internal drivers of at-risk problematic gambling behavior among college students are unknown. Gambling researchers have identified this population as at-risk for developing gambling problems based on demographic criteria (i.e., age, race, gender, and education) [14-16], but the internal drivers of problematic gambling behavior remain unknown [17]. Simon M [18] stressed that unless researchers demonstrate through their studies a good understanding of the causes of problem gambling; effective treatments of problem gambling will prove difficult to develop. In fact, there are no empirically validated problem gambling treatment programs [8]. Choice Theory can provide a framework for understanding the internal drivers associated with at-risk gambling behavior among college students.

The purpose of this quantitative study was to examine the internal drivers associated with at-risk gambling behavior using Choice Theory for undergraduate college students enrolled in general education courses at Campbell University. Because other theories have failed to identify the drivers of problem gambling among college students, Choice Theory was used to determine if the need for power and the need for achievement can predict atrisk problem gambling among the target population. This study yields information that is critical to understanding the role of internal drivers in at-risk gambling behavior among college students. It is the hope that this information may prove useful for developing screening, prevention, and intervention strategies for this population.

Method

A G*Power Analysis was conducted to determine the appropriate sample size of 300 subjects. Three hundred undergraduate college students enrolled at Campbell University consented to participate in the research study. Of this number 22 participant responses were removed from the data analysis because all scales and instruments were not completed in their entirety, leaving a total of 278 complete survey results. Eighty-nine of the participants were male, and 189 were female. Participants represented undergraduate status across grade levels with 85 participants identifying as freshman-level students, 65 participants identifying as sophomore level students, 99 participants identifying as junior level students, 27 participants identifying as senior level students, and 2 participants did not indicate status level.

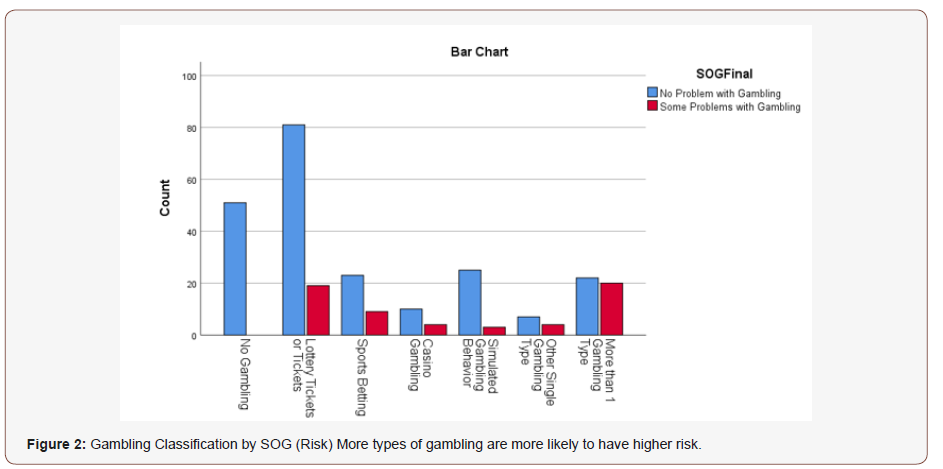

Participants reported their preference for type of gambling and were directed to select multiple options. Participant selections ranged from indicating no interest in a type of gambling to interest in up to four different types of gambling. Twenty-two participants indicated a preference for casino gambling, four participants indicated an interest in internet gambling, 129 participants indicated an interest in lottery tickets, 32 indicated interest in simulated gambling behavior, 16 indicated interest in slot machines, 58 indicated interest in sports betting, nine indicated interest in wagering drinks, and 51 reported no specific gambling interest.

The sample mean on the Desirability for Control scale was 98.74 with a standard deviation of 13.13. The sample mean score for the need for achievement was 7.24. A Pearson correlation was used to determine the strength of the correlation between the two variables resulting in a weak positive correlation between the need for control and need for achievement (r=0.10).

Result

The South Oaks Gambling Screen was utilized to determine classification for being at-risk of developing gambling disorder. Participant scores ranged from 0 to 10 with a mean score of 0.37. Scores indicated three different classifications of gambling behavior: (a) score of zero indicates no problem, (b) score ranging from one to four indicates at-risk status for developing gambling disorder, and (c) a score of five or higher indicates a probable pathological gambler. Two hundred and nineteen participants received a score of zero, indicating no problem or risk of developing gambling disorder, 56 participants received a score classifying them as having some problem, and three participants received a score classifying them as being a probable pathological gambler. Therefore, 59 participants (21.22 percent) were identified as meeting classification of being at-risk of developing gambling behavior, meaning those who received a score of one or greater.

Research question one examined the relationship between the need for control and being at risk of developing gambling disorder among undergraduate college students. Results from an independent samples t-test indicated that there was not a significant relationship between the classification status of being at-risk of developing gambling disorder and need for control among college students. Individuals classified as being at-risk for developing gambling disorder (M= 97.52, SD= 1.66, N= 59) scored slightly lower on the need for control scale than individuals not at risk for developing gambling disorder (M= 99.06, SD= 0.90, N= 219), t (276) = 0.80, p >.05. However, the difference was not significant at the p=0.43.

Research question two examined the relationship between need for achievement and being at risk of developing gambling disorder among undergraduate college students. As predicted, results from an independent samples t-test indicated that there was a significant relationship between classification status of being at-risk of developing gambling disorder and need for achievement among college students. Specifically, individuals classified as being at-risk for developing gambling disorder (M= 10.39, SD= 5.56, N= 59) scored higher on the need for achievement than individuals not at risk for developing gambling disorder (M= 6.39, SD= 4.08,N = 219), t (276) = -6.15, p <.001.

Research question three examined the relationship between gender, the need for control, and being at risk for developing gambling disorder. A multiple linear regression was used to predict the participant’s need for control based on gender and being at-risk for developing gambling disorder. The equation was not significant (F (2, 275) = 1.42, p>.05) with an R2 of 0.01. Therefore, we cannot reject the null hypothesis as there is not a significant relationship between.

Research question four examined the relationship between gender, need for achievement and being at risk of developing gambling disorder. A multiple linear regression was used to predict the need for achievement based on gender and being at-risk for developing gambling disorder. A significant regression equation was found (F (2, 275) = 25.89, p<.0001 with an R2 of 0.1585. When participant need for achievement was predicted, it was found that being at-risk for developing gambling disorder (β= -3.61, p=.001), and gender (β= -1.99, p=.001) (Figure 1&2).

Discussion

As previously discussed, gambling is a public health concern, particularly for college students. Of the college students who participated in this study, 21.22% met the criteria for being considered at risk of developing gambling disorder, which is comparable to a previous study reporting 17% of college students meet the criteria for gambling disorder [4]. This rate of prevalence of students at-risk in the sample reaffirms the need for ongoing support and intervention for gambling disorder prevention and interventions with young adults in the college setting.

There was not a significant relationship between the need for control and being at-risk for developing gambling disorder. Also, both gender and being at-risk of developing gambling disorder do not significantly predict the need for control among college students. In contrast there was a significant relationship between need for achievement and being at-risk for developing gambling disorder. This research finding suggests there is a connection between a drive for achievement and being considered at-risk for developing gambling disorder. Also, both gender and being at-risk of developing gambling disorder were significant predictors of need for achievement.

Acknowledgment

Research Grant sponsored by: NC Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS)/Division of Mental Health Developmental Disabilities and Substance Abuse Services/NC Problem Gambling Program/ www.morethanagamenc.org.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Burge AN, Pietrzak RH, Petry NM (2006) Pre/early adolescent onset of gambling and psychosocial problems in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. J Gambl Stud 22(3): 263-274.

- Jimenez Murcia S, Alvarez-Moya EM, Stinchfield R, Fernandez Aranda F, Granero R, et al. (2010) Age of onset in pathological gambling: clinical, therapeutic and personality correlates. J Gambl Stud 26(2): 235-248.

- Rahman A, Pilver C, Desai R, Steinberg M, Rugle L, et al. (2012). The relationship between age of gambling onset and adolescent problematic gambling severity. J Psychiatr Res 46(5): 675-683.

- Larimer M, Neighbors C, Lostutter T, Whiteside U, Cronce J, et al. (2012) Brief motivational feedback and cognitive behavioral interventions for prevention of disordered gambling: a randomized clinical trial. Addiction 107(6): 1148-1158.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). DSM-5: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th edn. Washington, USA.

- Glasser W (1984) Our basic needs-the powerful forces that drives us. In Control theory: A new explanation of how we control our lives 1st edn. New York, USA, pp. 5-18.

- National Center for Responsible Gaming (NCRG) (2013) College gambling.

- Derevensky J, Sklar A, Gupta R, Messerlian C, (2010) An empirical study examining the impact of gambling advertisements on adolescents gambling attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 8(1): 21-34.

- Martin R, Usdan S, Cremeens J, Vail Smith K (2014) Disordered gambling and co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders among college students: An examination of problem drinking, anxiety and depression. J Gambl Stud 30(2): 321-333.

- Wubbolding RE (2002) Reality therapy Contemporary theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

- Ashley L, Boehike K (2012) Pathological gambling: a general overview. J Psychoactive Drugs 44(1): 27-37.

- Glasser W (1999) Choice theory: A new psychology of personal freedom. Harper Perennial.

- Howatt WA (2003) Choice Theory: A Core Addiction Recovery Tool. International Journal of Reality Therapy 22(2).

- Barnes G, Welte J, Hoffman J, Tidewell, M (2010) Comparisons of gambling and alcohol use among college students and noncollege young people in the United States. J Am Coll Health 58(5): 443-453.

- Huang JH, Jacob DF, Derevensky JL (2010) DSM-based problem gambling: increasing the odds of heavy drinking in a national sample of U.S. college athletes? J Psychiatr Res 45(3): 302-308.

- Stuhldreher WL, Stuhldreher TJ, Forrest KY (2007) Gambling as an emerging health problem on campus. J Am Coll Health 56(1): 75-88.

- Hodgins DC, Stea JN, Grant JE (2011) Gambling disorders. Lancet 378(9806): 1874-1884.

- Simon M (2006) Addictions without substance series: The conundrums of gambling. Drugs and Alcohol Today 6(3): 37-41.

-

Tracy Poe, Beth Vincent. The Efficacy of Choice Theory to Identify At-Risk Gambling Behavior in College Students. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 1(5): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000522.

Gambling Behavior, Gambling disorder, Behavioral condition, Gambling interest, Brain, Life-Risk, Behavior, Anorexia, Spectrum, Disorder, Addiction, Depressive, Stress, Food intake, Locomotion, Animal models; Nucleus accumbens; Medial prefrontal cortex; Serotonin 4 receptors, Social Services, Intoxicant, Optimism, Physiological ecology, Addiction, Rehabilitation, Behaviour, Optimistic, Neurological, Mental health, Cognitive, Mental capacity

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.