Research Article

Research Article

Multiple Drug Use Disorder in Homeless People with Severe Mental Illness

Rafael Fernández García-Andrade1,2,3,4*, Beatriz Serván Rendón Luna2, Miriam Manuela Tenorio2, Virginia Vidal Martínez5, Julia Sevilla Llewellyn Jones2, Elena Medina Téllez de Meneses1,6 and Blanca Reneses Prieto2,3,4

1Department of Psychiatry, Mental Health Street Team of Madrid’s Programme for the Psychiatric Care of the Homeless Mentally Ill, Spain

2Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry and Mental Health of the Clínico San Carlos Hospital, Spain

3Department of Psychiatry, Health Research Institute of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (IdISSC), Spain

4Faculty of Medicine, Complutense University, Spain

5Department of Psychiatry, Alcorcón University Hospital Foundation, Spain

6Department of Psychiatry, La Paz University Hospital, Spain.

Rafael Fernández García-Andrade, Department of Psychiatry, Mental Health Street Team of Madrid’s Programme for the Psychiatric Care of the Homeless Mentally Ill, Spain.

Received Date: July 04, 2019; Published Date: July 23, 2019

Abstract

Homeless people (HP) with severe mental illness (SMI) and with a comorbid diagnosis of Multiple Drug Use Disorder (MDUD) are one of the most vulnerable and most difficult populations to engage. The objective of this study was to analyze the factors that are associated with the MDUD in the HP SMI. A retrospective observational study was conducted, with a total sample of 146 patients from a psychiatric attention program for HP with SMI. Two groups of subjects with and without a diagnosis due to MDUD were studied and compared with each other. Sociodemographic and clinic variables were collected. A logistic regression analysis was made in which the variables with statistically significant differences between the two groups were included. The following factors associated with MDUD were identified: duration of the mental disorder up to one year (p=0.002) OR=7.41; diagnosis of personality disorder (p=0.023) OR=6.45, history of criminal behavior (p=0.002) OR=5.88; age under 45 years old (p=0.003) OR=5.51. More studies are required because of the implication that it has in the adequate therapeutic approach of this population.

Keywords: Dual Diagnosis; Homeless Population; Homelessness; Severe Mental Illness

Abbreviations: HP: Homeless People; SMI: Severe Mental Illness; MDUD: Multiple Drug Use Disorder

Introduction

Homeless people (HP) with severe mental illness (SMI) and with a comorbid diagnosis of Multiple Drug Use Disorder (MDUD) are one of the most vulnerable and most difficult to engage in order to receive medical attention population, raising major challenges in their treatment of adverse health conditions. On one hand, the lack of housing is an important social and health issue in western countries. Epidemiological studies show that between 20% and 40% of HP suffer from SMI [1]. On the other hand, substance abuse is the most common and clinically significant comorbidity among people with serious mental illness [2], with some estimates indicating that half or more of people diagnosed with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses would qualify as having a substance use disorder over their lifetime [1]. And homelessness itself exacerbates both symptoms of mental illness and substance abuse and makes recovery less likely [3]. American studies suggest that approximately 50% to 70% HP with SMI also abuse of psychotropic drugs [2], although some suggest that the real prevalence would be much higher [3].

To our knowledge there is no research about the intragroup differences in relation to substance consumption in HP with SMI; although these differences would have clear implications in the therapeutic approach of this population [4,5]. Since drug consumption is a fundamental obstacle to the recovery of mental health in people with SMI, directly related to an increased risk of presenting general health problems, perpetuating homelessness or presenting criminal behavior [2]. The main objective of the study was to analyze the factors associated to the comorbidity of SMI and MDUD in HP.

Methods

Design

An observational naturalistic study performed on a group of patients with a severe mental illness (SMI) in a situation of social exclusion, attended by the Mental Health Street Team of Madrid’s ‘Programme for the Psychiatric Care of the Homeless Mentally Ill [6,7]. The abovementioned programme provides social, health and psychiatric care for all adult homeless people in the municipality of Madrid with a SMI, and who for various reasons are not being monitored by the standard mental health network. For the purpose of the ‘‘Programme for the Psychiatric Care of the Homeless Mentally Ill’’ the diagnostic categories according to ICD-10 [8] included in SMI are: Schizophrenic disorders (F20.x), persistent delusional disorder (F22.x), induced delusional disorder (F24.x), schizoaffective disorder (F25.x), Other nonorganic psychotic disorder (F28 and F29.x), bipolar affective disorde (F31.x), Severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (F32.3.x), recurrent depressive disorder (F33), obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42.x), schizotypal disorder (F21.x), personality disorder (F60.x). As inclusion criteria for the study, the following were used

• HP with SMI.

• Have begun follow-up in ‘‘Programme for the Psychiatric Care of the Homeless Mentally Ill’’ among the years 2010 and 2015.

• Age between 18 and 75 years.

We followed the criteria of the Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FEANTSA) based on the European typology on homelessness and housing exclusion (ETHOS) to categorise a person as homeless [9]. We used the criteria of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [10] to define SMI using the diagnostic criteria of the ICD-10 [8], through the application of the International Neuropsychiatric Interview [11].

Sample

The sample study was selected from a total of 146 patients who had completed the Baseline Assessment Protocol (which is given to all subjects when they are included in the ‘‘Psychiatric care programme for the homeless mentally ill’’) from June 2010 to June 2015. Two groups were selected from this sample, depending on whether the diagnosis of Multiple Drug Use Disorder (MDUD) according to F19 of ICD-10 [8] was registered or not.

Ethical approval

The source of information was the Baseline Assessment Protocol. For each subject, an anonymized form was filled in by each patient (generating an anonymized database). This study was performed with the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Madrid’s Clínico San Carlos, in compliance with all the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki, and Spanish legislation on data protection.

Procedure

All patients were assessed with the variables present in the Baseline Assessment Protocol. This Protocol includes extensive information on sociodemographic (date of birth, sex, nationality, place of origin, years of evolution of homelessness, typology of homelessness according to ETHOS classification [9], level of education attained, best profession attained, presence of criminal behavior history) and clinical variables (diagnostic criteria of the ICD-10 [8] through the application of the International Neuropsychiatric Interview [11], the years of evolution of the mental disorder, psychotropic substances use record, the existence of previous contact with mental health services, the existence of previous hospitalization history and comorbidity with infectious disease).

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were described in terms of mean or frequency. For the comparison between the two groups of the quantitative variables, the t-student test was used (or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test). For the quantitative variables, the comparison between the groups was evaluated by χ² - test (or Fisher’s exact test when more of the 25% of the expected values were less than 5). Subsequently, a logistic regression analysis was performed with the Wald step method considering as a dependent variable the existence, or not, of the MDUD diagnosis comorbid with SMI; and as independent variables those that showed statistical significance (p<0.05) in their univariate association with main variable (comorbid MDUD). For all of these tests, the level of significance accepted was 5%. The process and analysis of the data was carried out using the statistical package SPSS, version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, EE.UU.).

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical variables in HP with SMI

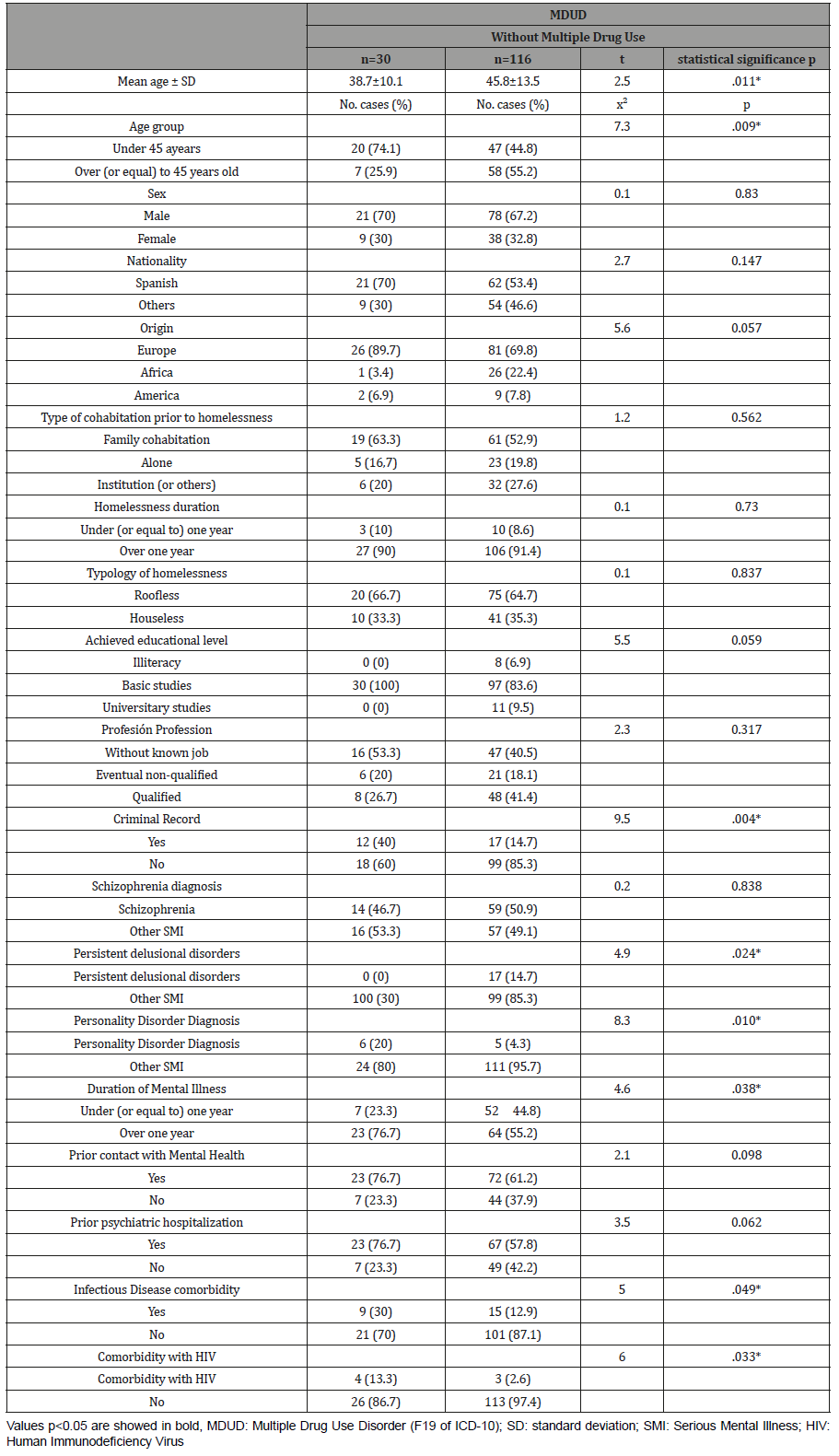

In the descriptive analysis of HP with SMI sample (N=146), it was found that up to 54.8% (n=80) had psychotropic substances use record (past and/or current), and of them, a 37.5% (n=30) had a diagnosis of Multiple Drug Use Disorder (MDUD). In the comparative analysis of both groups Table 1, with “MDUD” and “without multiple drug use”, statistically significant differences were observed in: age (p=0.011), age group (p=0.009), the presence of criminal behavior record at the time of inclusion in the Programme (p=0,004), the diagnosis of persistent delusional disorder (F22 of the ICD-10) (p=0,024), the diagnosis of personality disorder (F60 of the ICD-10) (p=0,010), duration of the mental disorder (p=0,038), comorbidity with infectious disease (p=0,049) and comorbidity with HIV (p=0,033).

Table 1: Sociodemographic and clinical differences between patients with and without diagnosis of MDUD in HP with SMI.

Logistic regression model

The model obtained with logistic regression showed a good adjustment (x2 Hosmer and Lemeshow = 1,651; gl=6; p=. 949), correctly classifying 83.3% of the sample with a sensitivity of 96.2% and a specificity of 33.3% with a cut-off value of 0.5 in the regression equation; and R-square values of Cox and Snell = 0.230 and R-square values of Nagelkerke 0.361.

The four variables finally included in the logistic regression model were: age group (x2 Wald=8.90; gl=1; p=0.003); history of criminal record (x2 Wald=10).0; gl=1; p=0.002), the diagnosis (x2 Wald=5.13; gl=1; p=0.0023) and the duration of mental disorder (x2 Wald=9.20; gl=1; p=0.002).

The odds ratios (OR) for these variables showed that, the duration of mental disorder over one year, multiplied by seven the risk of the diagnosis of comorbid MDUD (OR=7.41;95% CI=2.0- 27.1). The diagnosis of Personality Disorder with respect to other diagnoses increased the risk of the diagnosis of comorbid MDUD by six times (OR=6.45; 95% CI=1.2-32.3). The presence of a criminal record increased the risk up to five times (OR=5.88; 95% CI=1.9-17.6). And the age under 45 years old quintupled that risk (OR=5.51; 95% CI=1.7-16.9).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study that simultaneously analyzes a wide variety of factors associated with the comorbidity of SMI and MDUD in HP. The main finding of this study is that, in the population of HP with SMI: the age under 45 years, the presence of a history of criminal behavior, the diagnosis of personality disorder and the duration of mental disorder over one year, are the most important risk factors for the diagnosis of MDUD.

The mean age was significantly lower in the group of those diagnosed with MDUD, and the risk of developing this disorder multiplied by five for those under 45 years of age. The association of psychotropic substance use with younger populations has been described in other HP studies in Western countries [1]. To explain this phenomenon, we suggested that young adults in homelessness are more likely to be engage in riskier patterns of consumption [12].

Our results indicate that for HP with SMI, the presence of criminal behavior antecedents quintupled the risk of MDUD diagnosis. In fact, some studies on the general population of adults with SMI have found that substance abuse is the main cause of crime and not mental illness in itself. And, in this sense, it is possible that for HP with SMI, several causal pathways underlie the relationship between MDUD and the existence of criminal behavior antecedents; such as, for example, that the disinhibition effect of drug and alcohol abuse may cause some HI with SMI to exhibit problematic behaviour on the street, thereby increasing the risk of criminal altercations [6,13].

A recent study [14] shows a strong association between homelessness and personality disorder. In our study, the diagnosis of personality disorder, compared to other diagnoses, increased the risk of comorbid MDUD diagnosis by six times. It is also documented [15] that co-occurrence of antisocial personality disorder with substance use disorder has a cumulative effect on rates of criminal behavior. However, our results suggest that the relationship between SMI, personality disorder and substance abuse is complex and deserves further study.

HP with SMI, exposure to drugs and alcohol on the streets is constant [16] and longer duration of mental disorder may increase the risk of consumption. In this sense, the duration of the mental disorder over one year, in our sample, multiplied by seven the risk of the diagnosis of comorbid MDUD.

Other findings from our study are significantly higher rates of comorbid infectious diseases (and more specifically Human Immunodeficiency Virus, HIV) in the group of those diagnosed with MDUD. In this sense, it has been shown that among HP, there is an increase in the rates of infectious diseases such as HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis [1]. These diseases are predictors of mortality among HP [17]. In the United States, with respect to racial/ethnic differences in the substance abuse rates of HP with SMI, African Americans are more likely to abuse cocaine and heroin than non-African Americans. However, whites have higher overall life rates and are more likely to abuse drugs such as powdered cocaine, alcohol, hallucinogens and inhalants [18]. But obviously, the data provided in this respect are difficult to extrapolate to the Spanish social reality. In our study, the percentage of Europeans was significantly higher in the group of those diagnosed with MDUD, while the percentage of Africans was significantly higher in the group than those who did not use multiple drugs. HP presents high rates of visits to emergency services, as well as hospitalizations. This pattern is observed in many countries and health care systems, even in countries with and without universal health insurance [1]. Substance abuse and mental health disorders are risk factors for becoming a frequent user of these services [1,19-21]. In the same line, it is not surprising that, in our sample, a significant trend of higher rates of previous hospitalization was observed in the group of those diagnosed with MDUD.

Conclusion

This is the first study that simultaneously analyzes a wide variety of factors associated with the comorbidity of SMI and MDUD in HP. The main finding of this study is that, in the population of HP with SMI: the highest youth, the history of criminal behavior, the diagnosis of personality disorder, and greater duration of mental illness, are the most important risk factors for comorbid MDUD.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted with great caution because the sample size was small, and there is the possibility of retrospective bias that might affect the results. It is necessary, therefore, to undertake further larger, prospective research studies.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare the absence of conflict of interests. This study was carried out with its own resources and had no external funding.

References

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M (2014) The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. The Lancet 384(9953): 1529- 1540.

- Drake R, McHugo G, Xie H, Fox M, Packard J, et al. (2006) Ten-year recovery outcomes for clients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32(3): 464-473.

- Henwood BF, Padgett DK, Smith BT, Tiderington E (2012) Substance Abuse Recovery after Experiencing Homelessness and Mental Illness: Case Studies of Change Over Time. J Dual Diagn 8(3): 238-246.

- Serge L, Kraus D, Goldberg M (2006) Services to Homeless People with Concurrent Disorders: Moving Towards Innovative Approaches. Vancouver, Canada.

- Padgett DK, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A (2001) Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: comparing Housing First with Treatment First programs. Community Ment Health J 47(2): 227-232.

- Fernández García Andrade R, Serván B, Medina E, Vidal V, Bravo M, et al. (2018) Criminal behavior among homeless individuals with severe mental illness. Spanish Journal of Legal Medicine 44(2): 55-63.

- Fernández García Andrade R, Serván B, Reneses B, Vidal V, Medina E, et al. (2019) Forensic-psychiatric assessment of the risk of terrorist radicalisation in the mentally ill patient. Spanish Journal of Legal Medicine 45(2): 59-66.

- World Health Organization (2003) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Washington: World Health Organization, USA.

- Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (2012) On the way home? FEANTSA monitoring report on homelessness and homeless policies in Europe. FEANTSA, Brussels, Europe.

- Ruggeri M, Leese M, Thornicroft G, Bisoffi G, Tansella M (2000) Definition and prevalence of severe and persistent mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 177: 149-155.

- Guy W (1976) Clinical Global Impressions. In: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology revised. National Institute of Mental Health: Rockville.

- Hadland SE, Marshall BD, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner JS, et al. (2011) A comparison of drug use and risk behavior profiles among younger and older street youth. Subst Use Misuse 46(12): 1486-1494.

- Fernández García Andrade R, Serván B, Medina E, Vidal V, Reneses B (2019) Mental illness and social exclusion: Assessment of the risk of violence after release. Rev Esp Sanid Penit.

- Tsai J (2017) Lifetime and 1-year prevalence of homelessness in the US population: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Public Health (Oxf) 40(1): 65-74.

- Roy L, Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, Latimer EA, Ayllon AR (2014) Criminal behavior and victimization among homeless individuals with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv 65(6): 739-750.

- Henwood BF, Padgett DK, Smith BT, Tiderington E (2012) Substance Abuse Recovery after Experiencing Homelessness and Mental Illness: Case Studies of Change Over Time. J Dual Diagn 8(3): 238-246.

- Feodor Nilsson S, Hjorthoj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M (2014) Suicide and unintentional injury mortality among homeless people: a Danish nationwide register-based cohort study. Eur J Public Health 24(1): 50- 56.

- Ma GX, Shive S (2000) A comparative analysis of perceived risks and substance abuse among ethnic groups. Addict Behav 25(3): 361-371.

- Hwang SW, Chambers C, Chiu S et al. (2013) A comprehensive assessment of health care utilization among homeless adults under a system of universal health insurance. Am J Public Health 103(2): 294-301.

- Bharel M, Lin WC, Zhang J, O’Connell E, Taube R, et al. (20013) Health care utilization patterns of homeless individuals in Boston: preparing for Medicaid expansion under the affordable care act. Am J Public Health 103(2): 311-317.

- Capp R, Rosenthal MS, Desai MM, Kelley L, Borgstrom C, et al. (2013) Characteristics of Medicaid enrollees with frequent ED use. Am J Emerg Med 31(9): 1333-1337.

-

Rafael Fernández García-Andrade, Beatriz Serván Rendón Luna, Miriam Manuela Tenorio, Virginia Vidal Martínez, Julia Sevilla Llewellyn Jones, Elena Medina Téllez de Meneses, et al. Multiple Drug Use Disorder in Homeless People with Severe Mental Illness. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 2(3): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000536.

Homeless, Population, Mental illness, Comorbid diagnosis, Psychiatric attention, Sociodemographic, Logistic regression, Mental disorder, Dual Diagnosis, Epidemiological, Comorbidity, schizophrenia, Exacerbates, Psychotropic drugs, Naturalistic, Psychiatric Care, Delusional disorder

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.