Research Article

Research Article

Development of the Attitudes toward Pornography Scale

Mark A Whatley* and Amber M Brock

Department of Psychology, Valdosta State University, USA

Mark A Whatley, Department of Psychology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, GA 31698-0100, USA.

Received Date: January 10, 2018; Published Date: January 23, 2019

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to develop an attitude toward pornography scale in order to examine student beliefs and encourage further exploration of such attitudes. Participants, 63 males and 186 females, responded to 78 statements, on a seven point scale, regarding their pornography attitudes and beliefs. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood with Varimax rotation. The initial factor analysis extracted 20 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Based on the screen plot, a two factor solution was deemed appropriate. Factor 1 was labeled “BENEFICIAL” and accounted for 25.34% of the variance. The coefficient of variation for Factor 1 was .33. The reliability (internal consistency) of Factor 1 was .87. Factor II was labeled “DETRIMENTAL” and accounted for 6.77% of the variance. The coefficient of variation for Factor 2 was .33. The reliability (internal consistency) of Factor II the scale was .84. An initial examination of the validity of Factor 1 and Factor 2 was supported (ps ≤ .011). A series of one-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine whether bias existed as a function of subject characteristics. Significant differences were found in both Factor 1 and Factor 2 with respect to subject sex and subject race. Males and Blacks reported more positive attitudes toward pornography than did females and Whites. Further research investigating the sex and race biases, as well as the construct validity of the scale, is warranted.

Keywords:Pornography scale; Pornography attitudes: Sex differences

Introduction

Pornography is a rapidly growing industry in the United States. Between the years 2005 and 2006, adult entertainment revenue increased by 13% and grossed a total of 2.8 billion dollars [1]. The revenue surpassed that of large corporations, such as Microsoft and Google [2]. In 2008, at least one adult website was visited each month by 36% of internet users [1]. The growth of this controversial industry has led to differential perceptions regarding its impact.

In a college student sample, Sloderbeck DJ [3] found that almost 90% of the males and 50% of the females viewed pornography. Given the rate of viewing pornography among college students, their pornography attitudes have been examined O’Reilly, et al. [4], as well as the attitudes of feminists (Cowan, 1992) and victims of physical or sexual trauma [5]. These investigations have used large scale survey techniques [4] or a series of unconnected statements [6]. Additionally, researchers have examined the characteristics of college students who consumes pornography Wampler KS & Wasserman I [7,8] as well as its effect on one’s self-concept and interpersonal relationships [8-10].

Relatively recent research has examined the possible effects of viewing pornography. For example, Manning C [11] reported that marital relationships are experiencing negative consequences as a result of internet pornography, such as increased aggression and undervaluing of monogamy. Others report that moderate consumption of pornography can strengthen interpersonal relationships [12]. With so many views of pornography and its potential impact on social relationships, a need for a scale to measure attitudes toward pornography is clear.

The utility of such a scale will serve researchers and clinicians alike in their attempts to further understand attitudes toward pornography and their link to cognitions, emotions, and behaviors. The primary goal of this study was to develop a psychometrically sound assessment of pornography attitudes using scale development techniques and to uncover the number of latent constructs underlying attitudes toward pornography. A secondary goal was to develop an assessment instrument that would allow feasibility, economy, and flexibility in research situations.

Method

Participants

The participants were 63 male and 186 female undergraduate students conveniently selected from Valdosta State University. They received no compensation or extra credit for their participation. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 45 with a mean age of 19.14 and a standard deviation of 2.34. The ethnic background of the sample was 48% White, 46.8% African American, .4% Hispanic, .4% Asian, .4% American Indian, and 3.6% from other racial backgrounds. One person chose not to indicate racial information. The participant sample consisted of 66.4% freshmen, 23.2% sophomores, 6% juniors, and 4.4% seniors. The majority of the sample (95.6%) indicated a heterosexual orientation.

Materials

An item pool of 78 items was generated to address attitudes toward pornography. Examples of the items within the scale are: “Pornography can help foster intimacy in a relationship.”, “I believe that pornography is harmful to a relationship.”, “Pornography is a form of entertainment.”, “Pornography leads to rape.”, and “I feel insecure about myself when I view pornography.” Each item was scored on a seven point scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Negatively worded statements were reverse scored so that higher scores indicate more positive attitudes toward pornography.

Procedure

The participants completed the experiment either individually or in a group. Students were asked to participate in an experiment attempting to measure the attitudes toward pornography in college students. If students refused, then they were thanked and not bothered any further. If students agreed, they were given a four page survey to complete by following the directions.

On the first page of the survey packet, students read they would be answering questions that examined one’s attitudes toward pornography. They were instructed not to put their name or other identifiable information on the survey and to leave any questions they felt uncomfortable answering blank. Next, students completed demographic information and answered a series of questions that would be used as an initial validity check of the finalized scale. These questions were not part of the 78 pornography attitude statements. On a 7-point scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) participants indicated their level of agreement with the following statements: “I consider myself a religious person.”; “I am comfortable displaying affection in public.”; “Pornography has a negative effect on social relationships.”; “When in a relationship, viewing pornography secretly is cheating.”; “Watching pornography is a great way to learn new sexual techniques.”; “I view pornography at least once a week.”; “I watch programs with pornographic content with my sexual partners.”; and “I view pornography that is different from my sexual orientation.”

Instructions to participants

On the second page of the survey packet, they read: Relatively little is known about college students’ attitudes toward various forms of sexually explicit material. The purpose of this survey is to gain a better understanding of what college students think and feel about pornography. Pornography is material (i.e., books, paintings, photos, films, etc.) that show erotic or sexually suggestive behavior that elicits sexual excitement in the observer. Please read each item carefully and consider how you feel about each statement. There are no right or wrong answers to any of these statements, so please give your honest reactions and opinions. Please read each statement carefully and respond by using the following scale: At the end of the instructions, the 7-point rating scale was presented and continued at the top of subsequent pages. After participants completed the survey, they were thanked and instructed how they could obtain the results of the study.

Results

An alpha level of .05 was used to evaluate statistical significance and r was used as the effect size (Rosenthal, 1991).

Factor Analysis

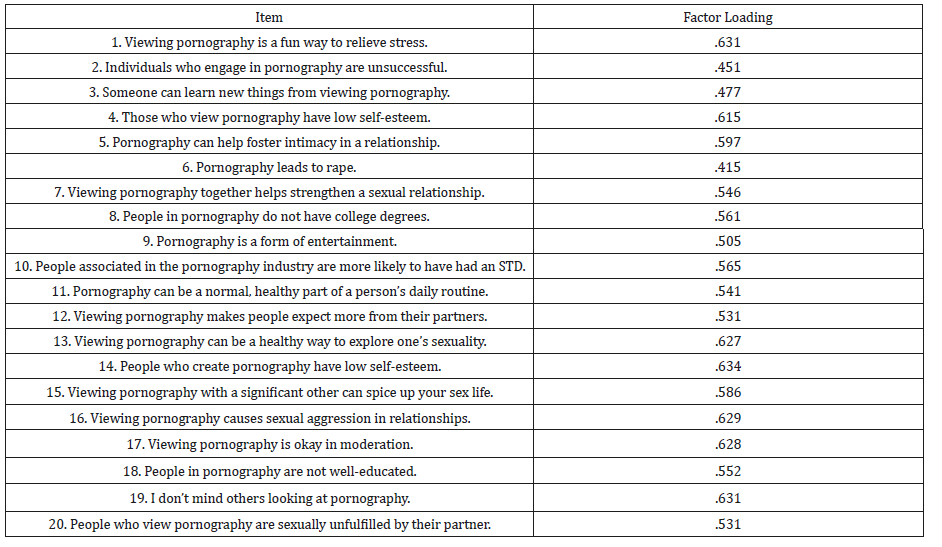

The data was contained by using SPSS version 22.0. The factor analysis extracted 20 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Based on the screen plot, a three and four factor solution was investigated but did not prove optimal. Further investigation showed that a two factor solution was appropriate. Factor 1 was labeled “BENEFICIAL” and accounted for 25.34% of the variance. The coefficient of variation for Factor 1 was .33. The coefficient of variation allows a comparison and assessment of the amount of variation that exists in a measure (Howell, 1992). The higher the value the more variation exists, and the greater the variation, the greater the ability of a measure to discriminate between groups. The reliability of the scale was .87. Factor 2 was labeled “DETRIMENTAL” and accounted for 6.77% of the variance. The coefficient of variation for Factor 2 was .33. The reliability of the scale was .84 (Table 1).

Table 1: Factor loadings for the attitudes toward pornography scale.

Note: The odd number items represent Factor 1 and the even number items represent Factor 2.

Sex Differences in attitudes toward pornography

Beneficial analysis: A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether sex differences were present in pornography attitudes. The analysis was significant, F (1, 247) = 4.13, p = .043 (r = .13). Males endorsed more beneficial attitudes toward pornography (M = 4.09, SD = 1.29) than females (M = 3.70, SD = 1.32)

Detrimental analysis.A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether sex differences were present in pornography attitudes. The analysis was significant, F (1, 246) = 4.52, p = .035 (r = .13). Males endorsed fewer detrimental attitudes toward pornography (M = 3.13, SD = 1.11) than females (M = 3.49, SD = 1.15).

Race differences in attitudes toward sexual behaviors

A one-way ANOVA was used to determine whether race differences were present in beneficial and detrimental attitudes toward pornography. Due to the distribution of racial categories, only Whites (n = 120) and Blacks (n = 117) were compared.

Beneficial analysis. The analysis was significant, F (1, 235) = 13.47, p < .001 (r = .23). Blacks endorsed more beneficial attitudes toward pornography (M = 4.13, SD = 1.16) than Whites (M = 3.51, SD = 1.43).

Detrimental analysis. The analysis was significant, F (1, 234) = 25.79, p < .001 (r = .32). Whites endorsed more detrimental attitudes toward pornography (M = 3.74, SD = 1.21) than Blacks (M= 3.02, SD = 0.94).

Academic standing differences

A one-way ANOVA was used to determine whether academic standing differences were present in pornography attitudes. Due to the distribution of academic standing categories, Freshmen (n = 166) were compared to Non-Freshmen (n = 84). The academic standing differences were not significant for beneficial (p = .203) or detrimental (p = .625) attitudes.

Correlational analyses

A series of bivariate correlational analyses were conducted to examine the initial validity of the scale. The results showed that both beneficial and detrimental attitudes toward pornography significantly correlated in expected ways with “I consider myself a religious person.” [r (248) = -.32, p < .001 and r (247) = .27, p < .001]; “I am comfortable displaying affection in public.” [r (249) = .17, p = .007 and r (248) = -.17, p = .009]; “Pornography has a negative effect on social relationships.” [r (249) = -.52, p < .001 and r (248) = .52, p < .001];

“When in a relationship, viewing pornography secretly is cheating.” [r (249) = -.55, p < .001 and r (248) = .48, p < .001]; “Watching pornography is a great way to learn new sexual techniques.” [r (245) = .66, p < .001 and r (244) = -.40, p < .001]; “I view pornography at least once a week.” [r (247) = .28, p < .001 and r (246) = -.16, p'' = .011]; “I watch programs with pornographic content with my sexual partners.” [r (247) = .37, p < .001 and r (246) = -.30, p < .001]; “I view pornography that is different from my sexual orientation.” [r (244) = .26, p < .001 and r (243) = -.19, p = .003].

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to create a measure to objectively assess attitudes toward pornography. The results indicated that the pornography attitudes scale consists of two factors: beneficial and detrimental. The results of the analyses on participant sex and race tentatively suggest that such attitudes are moderated by these factors. Although the sample was insufficient to examine additional racial and academic classification differences, Black students endorsed more beneficial and detrimental pornography attitudes than Whites (Fs ≥ 13.47). Additional research is necessary to determine whether student ethnicity significantly impacts the scale and whether academic standing (i.e., freshmen, sophomore, junior, and senior) differences exist.

The results of the study indicate that the initial psychometric properties of the scale are acceptable. The reliability of Factor 1 and Factor 2 are modest, and the coefficient of variation suggests both Factors possess divergent validity. In addition, the correlational analyses provide initial support for the construct validity of the scale.

One concern of the study involves the geographical location of the sample. The scale was developed using students from a regional university in South Georgia. This population could differ in important ways from the student populations of other colleges and universities. A second concern is that only intro to psychology students and psychology majors were involved. Previous research shows that attitudes differ as a function of majors. Because psychology majors tend to be more open in general, they may tend to be more positive in their attitudes toward pornography compared to other majors. Clearly, the pornography attitudes scale should be investigated using a more diverse student population to examine whether the sex and racial differences found are generalizable to other populations. Additionally, future research will help establish construct validity of the scale.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Edelman B (2009) Red light states: Who buys online adult entertainment? Journal of Economic Perspectives 23(1): 209-220.

- Ropelato J (2011) Internet pornography statistics. Internet Filter Software Review.

- Sloderbeck DJ (2010) Pornography viewing frequency: Associations with sexual preferences and relationship satisfaction among college men and women. Boise State University, USA.

- O’Reilly S, Knox D, Zusman ME (2007) College student attitudes toward pornography use. College Student Journal 41(2): 402-406.

- Broman CL (2003) Sexuality attitudes: the impact of trauma. J Sex Res 40(4): 351-357.

- Evans-DeCicco JA, Cowan G (2001) Attitudes toward pornography and the characteristics attributed to pornography actors. Sex Roles 44(5-6): 351-361.

- Parker TS, Wampler KS (2003) How bad is it? Perceptions of the relationship impact of different types of Internet sexual activities. Contemporary Family Therapy 25(4): 415-430.

- Stack S, Wasserman I, Kern R (2004) Adult social bonds and use of Internet pornography. Social Science Quarterly 85(1): 75-89.

- Bridges AJ (2003) Romantic partners’ use of pornography: Its significance for women. J Sex Marital Ther 29(1): 1-14.

- Schneider JP (2000) Effects of cybersex addiction on the family: Results of a survey. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity 7(1-2): 31-58.

- Manning JC (2006) The impact of Internet pornography on marriage and the family: A Review of the Research. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 13(2-3): 131-165.

- Dreyfus EA (2009) Fast way to sort out husband’s interest in internet pornography. Selfhelp Magazine 32(4).

-

Mark A Whatley, Amber M Brock. Development of the Attitudes toward Pornography Scale. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 1(4): 2019. OAJAP. MS.ID.000517.

Pornography scale, Pornography attitudes, Sex differences, Behaviors, Cognitions, Addiction, Rehabilitation, Behaviour, Optimistic, Neurological, Mental health, Cognitive, Mental capacity

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.