Review Article

Review Article

Luxury Strategy by Simple and Pleasant Life-Style Brand of MUJI — Flagship Store Strategy for Large Store Location

Shin’ya Nagasawa1* and Norihiro Suganami2

1Graduate School of Business and Finance, Waseda University, Japan

2Tanseisha Co. Ltd., Japan

Shin’ya Nagasawa, Graduate School of Business and Finance, Waseda University Tokyo, Japan.

Received Date: August 14, 2020; Published Date: September 01, 2020

Abstract

Most of the luxury brands have flagship stores. In recent years, daily fashion brands and SPA brands such as UNIQLO and MUJI also have flagship stores. Both flagship stores are large stores, located in special places such as Ginza for brand-building. However, flagship store importance is not only Place of the marketing mix (4Ps) but also Product, Price, Promotion. In this article, we investigate flagship store strategy and the relationship between flagship store strategy and brand building by the overseas cases of MUJI.

Keywords: MUJI; Flagship store; Store location; Brand building; Luxury strategy

Introduction

Not only luxury brands, but also daily fashion brands and SPA (Specialty store retailer of Private label Apparel) brands such as UNIQLO and lifestyle fashion brands such as MUJI have found success in opening flagship stores in prime locations like Ginza. As many companies are pursuing a market entry strategy based on flagship stores, it has become regarded as a conventional means for expanding overseas, but attention is currently focused solely on the opening of stores in such prime locations and the luxurious stores themselves.

However, as Japanese retailers struggle to expand overseas, UNIQLO has been achieving success in overseas expansion with the opening of flagship stores. This is surprisingly the same as how European and American luxury brands, which are on the opposite end of the spectrum from SPA brand of UNIQLO, expanded in Japan by opening flagship stores (Kapferer and Bastien [1]; Kapferer JN [2]; Nagasawa S [3,4]). This means that the flagship store strategy is similarly being adopted by Western luxury brands that are polar opposites from UNIQLO, which is a daily fashion retailer. Yet, does the fact that such companies are not only focusing on advertisements and promotions, but also spending a large amount of capital to open flagship stores, mean that flagship stores are taking on an aspect of brand building that cannot be achieved through advertising and promotions alone?

To answer that, Nagasawa and Suganami [5,6] arrived at the conclusion, by means of a flagship store strategy case analysis for Fast Retailing’s subsidiary UNIQLO, that it is important for a company’s flagship store strategy to contribute to brand building using, not only the element of Place (location), but each of the marketing mix (4Ps) of Product, Price, and Promotion to heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association. However, it could be said that the systematization of the flagship store strategy is not fully supported by the study of one case alone.

Thus, we seek to verify our hypothesis through a research method which includes, in addition to a review of the relevant literature, interviews with Satoru Matsuzaki, managing director and head of the Overseas Operations Division, at Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd. (at the time of the interview. Currently the president), the company that operates MUJI (Mujirushi Ryohin) [7].

Previous Studies on Flagship Stores

This section outlines previous studies on flagship stores and explains this paper’s position.

In previous studies, flagship stores are defined as follows. Nagasawa S [8] claims that while fashion related books tend to describe flagship stores (flagship shops) as “stores that carry all of a brand’s products,” they should be defined as “stores that carry all of a brand’s products while attracting the brand’s universe.” In literature from outside of Japan, Kozinetsa [9,10] indicates that the three general characteristics of flagship stores are that (1) they carry a single brand, (2) they are directly managed by the brand, and (3) they are operated more with the intention of brand building than the singular intention of profits. Moore CM et al. [11] argue that luxury brands’ flagship stores play an important role in market entry strategies.

Based on the previous studies, it can be said that brand building is an objective of flagship stores and that flagship stores play an important role in market entry, but previous studies have not covered the methods thereof.

Also, although the flagship store is defined, it is recognized as part of the business strategy such as store strategy and store opening strategy. For this reason, there is no deep discussion on flagship stores in Japan. Even in Kent and Brown [12], there has been no research on flagship store strategies and brand building that have dealt with Japanese companies nor daily fashion brands/ SPA brands such as UNIQLO and MUJI.

Regarding the location of luxury brand stores, as a series of studies comparing the locations of non-luxury brand stores, Kumagai and Nagasawa [13-16], but does not focus on flagship stores, especially non-luxury brand flagship stores.

This paper does not study the objectives of flagship stores or the location and extravagance of flagship stores using luxury brands’ flagship stores as examples, as previous studies have done. Rather, this paper elucidates the essence of the flagship store strategy and the methods thereof by taking up MUJI, “simple and pleasant life-style brand,” which carries products in the mid-price range and can be viewed as being on almost the opposite end of the spectrum from luxury brands, and also by incorporating examples from UNIQLO [5,6], which is similarly an SPA business.

In this paper, flagship store is defined as “a store that exhibits the brand’s essence” while flagship store strategy is defined as “a market entry strategy revolving around a flagship store that contributes to brand building by using all of the elements of Product, Price, Place (location), and Promotion to heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association,” and the specific methods and objectives thereof are discussed.

Accordingly, we also aim to verify each of the elements of Product, Price, Place (location), and Promotion in the study of the relevant literature and in the interviews.

Overview of Mujirushi Ryohin and MUJI

Mujirushi Ryohin emerged as Seiyu’s private brand label in 1980. Then in 1989, Seiyu transformed Mujirushi Ryohin’s Operations Department into a subsidiary company, thereby founding Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd., which ended up breaking away from Seiyu in 1990.

By the end of February 2020, they had expanded to 477 stores in Japan and 556 stores overseas throughout China (273 stores), Hong Kong (21 stores), Taiwan (49 stores), Korea (40 stores), the United States (19 stores), Thailand (19 stores), Singapore (12 stores), the United Kingdom (11 stores) and so on, with consolidated sales in FY2019 of 438.7 billion yen and operating profits of 36.4 billion yen, for an operating profit ratio of 8.3%. Their overseas (Asia + Europe) operations had sales of 153.3 billion yen and operating profits of 14.2 billion yen, for an operating profit ratio of 9.3%. They were actively developing overseas operations in FY2019 with 19 stores opening in Japan and 39 stores opening overseas (Ryohin Keikaku [17]).

Mujirushi Ryohin products emerged as Seiyu’s private brand based on the concept of inexpensive but quality products, as expressed in their slogan “lower priced for a reason.” Selection of materials, process inspection, and simplified packaging are still the three pillars of Mujirushi Ryohin’s policy to this day. Moreover, serving on the company’s advisory board are quintessential Japanese creative artists such as graphic designer Kenya Hara, product designer Naoto Fukasawa, and interior designer Takashi Sugimoto, and other creative artists, such as deceased graphic designer Ikko Tanaka and fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto, have also belonged to the company in the past. Despite the involvement of such top Japanese artists, it is also Mujirushi Ryohin’s characteristic style to not openly publicize those names. These characteristics can be seen as contributing to the maintenance of the unique philosophy upheld by Mujirushi Ryohin.

In expanding overseas, “MUJI” has been developed as a brand name. As such, the domestic brand produced by Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd. is called “Mujirushi Ryohin,” while the overseas brand is called “MUJI.”

MUJI’s Overseas Expansion

MUJI’s overseas expansion failure in Europe

MUJI developed operations overseas early, with the 155 m2 MUJI West Soho store being opened in central London in July of 1991, as their first overseas store. Their first Hong Kong store MUJI Ocean Center (291 m2) opened in November, and their first store in France MUJI ST. SULPICE (175 m2) opened in 1998, with a total of eight stores being opened overseas by the end of FY 2000. MUJI’s concept, which was connected with the Japanese spirit of Zen Buddhism namely the image of goods that cut down on waste and incorporated only the essentials, was well received in Europe. However, in 2001 the company ended up closing down four stores in France and one store in Belgium and reporting extraordinary losses of 1,385 billion yen. One reason attributed to these overseas expansion failures was that the rental fees being paid in order to have stores in prime locations were expensive and the stores were not able to yield continuous profits.

Publicity from the stores opening in prime locations and from special features in magazines, etc., was effective and business thrived around the opening of the stores, but due to products being imported from Japan, it is said that taxes and shipping costs made the price range 1.2 to two times higher than in Japan, depending on the product. The fact that selling prices were higher than in Japan is thought to have made it difficult to sell products to the masses, as was possible in Japan. Regarding promotions, advertising mainly came from publicity since, as per tradition, no advertisements other than grand opening announcements were produced, and the reason why MUJI was only accepted by a segment of highly receptive consumers, such as designers and creative artists, was attributed to the fact that they were unable to expose many general consumers to the brand.

It became difficult to sell to the masses like in Japan since the price range went from mid-priced to high-priced, which Managing Director Matsuzaki (at the time of the interview. Currently the president) described as “With the price range overseas being higher than in Japan we aren’t reaching the masses.” Despite opening stores in prime locations, in cases in which brand penetration and brand association were not able to be achieved quickly and brand building could not be accomplished, ultimately rental fees could not be paid, and failure ensued.

MUJI’s overseas expansion success – Italy case

From 2004, three years since the unprofitable stores had been closed, MUJI actively started opening stores in Europe. They opened MUJI MILANO Corso Buenos Aires (440 m2) as their first store in Milan, Italy in December of 2004. In London, rental fees amounted to 20% of sales, but in Milan, a mechanism for producing profits was created by opening a second-floor store, albeit in a prime location, in order to reduce rental fees. The following year, another store was opened in Milan and after profits started being produced, the company moved forward with having multiple stores throughout Italy, in Turin, Rome, Milan, and Bologna.

Chairman Tadamitsu Matsui of Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd., explains in the book “Mujirushi Ryōhin Sekai Senryaku to Keiei Kaikaku” (unofficial translation: Mujirushi Ryohin Global Strategy and Management Reform) (Watanabe [18,19]) that “Brand penetration was accelerated by opening stores exclusively in urban areas. Our development pattern of deepening penetration by opening more stores in urban areas as customer numbers started to increase was formulated in Italy. It is the same development pattern that foreign megabrands employ by going first to Tokyo and then to Osaka. Our company is also currently conducting operations in Germany.” Thus, the opening of stores in Italy succeeded under the strategy of opening stores in metropolises and also by opening stores not only in a prime location, but in an area of secondary prominence within a prime location. The difference in strategy did not simply concern location, rather products were also increasingly localized, local designers were appointed and products were conformed to sizes and styles that could be accepted locally. In terms of promotion, the company exhibited at Milano Salone in 2003 before opening the first store in Milan, and it resulted in brand penetration amongst highly receptive classes of consumers that could appreciate MUJI.

The Marketing Mix (4Ps) Analysis of MUJI Flagship Store

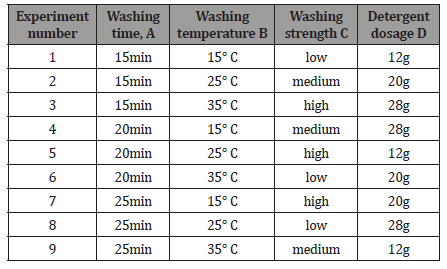

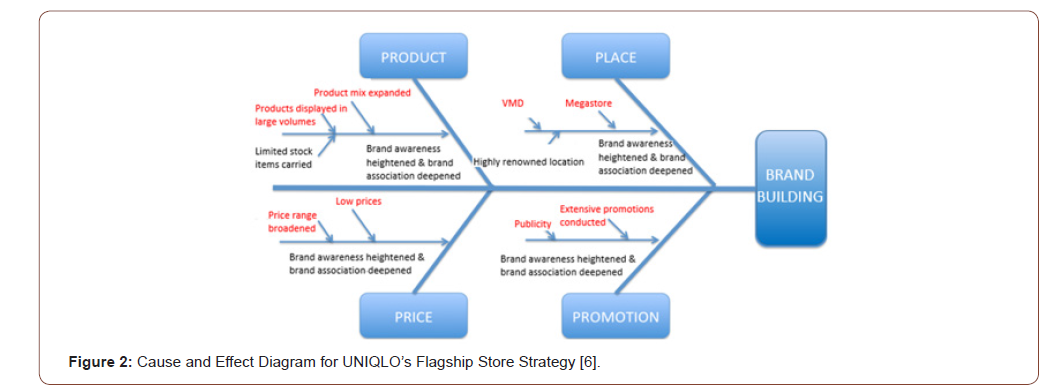

MUJI’s case of failure with their first London store, and their cases of success in Italy were compared using the marketing mix (4Ps) analysis, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1:The marketing mix (4Ps) Analysis for Flagship Store Strategy at the 1st London Store and Flagship Store Strategy in Europe from 2004.

It can be said that in London, the method for opening stores in Japan was basically traced without alteration. They actively opened stores, opening the first one in London and opening five more stores at the end of the same term. This is the same as how they actively opened over 20 stores over a span of one year in Japan. Although the prices are higher than in Japan, the same products as in Japan were put out and the same store format as in Japan was used, and just like in Japan no extensive promotions were conducted. The purchasing classes overseas and the way of viewing the MUJI brand is different than in Japan, which was described by Managing Director Matsuzaki as “In Japan, Mujirushi Ryohin products are something that normal people purchase. Yet, judging from the price range of our products overseas, it is people in the middle class and higher who are affluent to a certain degree that are purchasing MUJI products. Those people are picky about things.” It is thought that the strategy in London of simply tracing the way of doing things in Japan, even though the purchasing class was different, was unsuccessful in the end. In Italy, products were localized to conform to customers and the strategy for opening stores and promotional methods were reviewed.

When opening a store in a so-called prime location, even if the store garners a lot of attention the rental fees are burdensome and excluding cases in which the company has financial clout or an extremely high profit ratio, opening multiple stores thereafter is difficult. Moreover, being a store means that, in cases like MUJI’s where active promotions are not conducted, only consumers who use the surrounding area can become aware of the brand, and as a result brand penetration is delayed.

As such, MUJI which is a company that does not traditionally conduct active promotions, opened stores one by one in urban areas, which Managing Director Matsuzaki described as “a basic policy overseas of turning out profits one store at a time,” and slowly achieved brand penetration while simultaneously localizing products. Moreover, they succeeded at having multiple stores due to achieving brand penetration with highly receptive classes, through efforts such as exhibiting at Milano Salone.

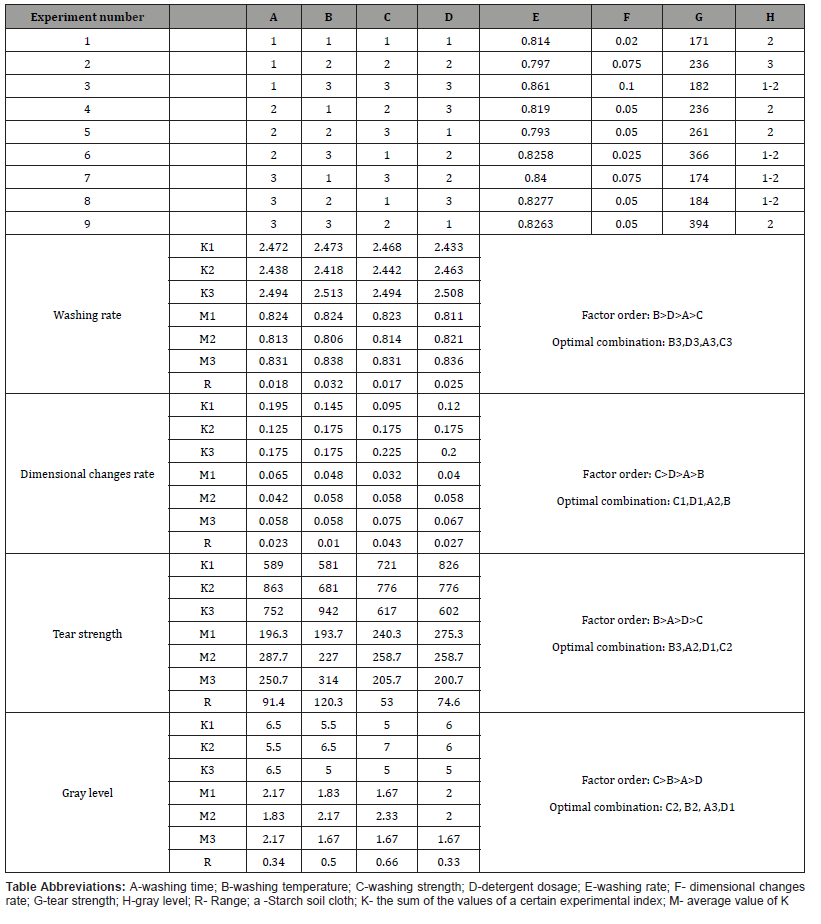

Comparison of UNIQLO’s and MUJI’s Flagship Stores

We elucidate the essence of the flagship store strategy through a comparative analysis of two opposing flagship store strategies, UNIQLO’s flagship store strategy which is centered upon active promotions and megastores in prime locations, and MUJI’s flagship store strategy in which active promotions are not conducted and stores are opened in areas of secondary prominence within a prime location (on second floor of building, not on the street level).

The comparison was conducted as shown in Table 2, using the New York Fifth Avenue store as an example of UNIQLO’s flagship store strategy, and using examples in China for MUJI since they have been actively opening stores in China since 2008 (Photo).

Table 1:The marketing mix (4Ps) Analysis for UNIQLO’s Flagship Store Strategy and MUJI’s Flagship Store Strategy in China

In the product category, UNIQLO conveys their “Made for All” brand concept to consumers by carrying all of their products, while MUJI tries to convey their brand to consumers more clearly by selecting products that conform to the local market, as they are not a fashion brand but a lifestyle brand. One feature that they share in common is that both convey their own Japanese image to consumers, with UNIQLO conveying a modern Japanese image using limited-stock items such as anime, and with there being more cognizance overseas than in Japan of MUJI products being Japanesestyle products.

In the price category, UNIQLO is in the low-price range and they conduct sales with limited-time prices, while MUJI is in the midprice range and they do not actively offer discounts, other than on seasonal items. Thus, UNIQLO effectively uses limited-time prices to convey a brand image of offering quality goods at low prices, while MUJI, being in the mid-price range, coveys the essence of their brand by not actively offering discounts.

Regarding location, in order to display an overwhelming quantity of products and effectively conduct promotions, UNIQLO opens megastores in definitively prime locations, while MUJI opens stores of a standard size in areas of secondary prominence within prime locations. Regarding the stores, both companies employ Japanese designers and have mechanisms for conveying a Japanese image. In the promotion category as well, UNIQLO actively and extensively conducts promotions, while MUJI primarily conducts promotions in-store instead of through extensive promotional campaigns.

One fundamental difference is UNIQLO’s and MUJI’s purchasing classes. As advertised through their slogan “Made for All,” UNIQLO aspires to offer products to all people regardless of generation, gender, or income. While MUJI is also perceived as a lifestyle brand in Japan, overseas their price range is different from Japan and their products are offered to highly receptive purchasing classes. Accordingly, in entering new markets, UNIQLO uses a flagship store strategy to actively build awareness of the UNIQLO brand amongst consumers and to sell low price range products to as many consumers as possible. Conversely, by allowing time for brand penetration to heighten brand awareness, it is thought that MUJI is trying to gradually expand the sale of products in the midto- high price range amongst highly receptive purchasing classes. This correlates to Managing Director Matsuzaki’s description that “overseas our brand image is extremely high compared to in Japan.”

Flagship Store Strategy Systematization

Based on the above analysis results, the flagship store strategies of MUJI and UNIQLO were organized into “cause and effect diagrams,” as represented by Figure 1 and Figure 2 respectively.

Although both strategies share in common the feature of opening stores in highly renowned locations, the strategies differ in that UNIQLO opens stores in definitively prime locations, while MUJI opens stores in prime locations albeit in areas of secondary prominence there. When the two strategies are considered in terms of other additional factors, they differ completely. However, when looking at the cause and effect diagrams, although there are differences in individual aspects, many points in common can be interpreted from the fact that each aspect is devised to contribute to brand building.

The two are similar in that as market entry strategies revolving around flagship stores, both have mechanisms in every category of product, price, place, and promotion, for making consumers aware of the brand, and both also have mechanisms for conveying a Japanese image. Therefore, adding the brand value of the nation of Japan is also considered to be effective in developing overseas operations.

Just as the extent of brand communication with consumers varies depending on the products being sold and the price range, the flagship store strategies also differ. UNIQLO experienced failure in opening stores in New Jersey using the same methods employed to expand in Japan. Likewise, MUJI experienced failure expanding in Europe using the same methods employed in Japan. Both companies learned through failure about differences from Japanese customers, and then succeeded by making modifications in problem areas. Many companies try to expand overseas after having great success in Japan, but rather than tracing those examples of success without alteration, they must employ a flagship store strategy that takes into consideration the extent of brand communication with consumers based on the products being sold and the price range.

It has been said regarding sources of brand equity that “Establishing a positive brand image in consumer memory—strong, favorable, and unique brand associations—goes hand-in-hand with creating brand awareness.” (Keller KL [20]) In other words, brand building is achieved through strengthening consumers’ brand awareness and brand association. We verify how the flagship store strategy can heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association based on the marketing mix (4Ps) analysis for MUJI’s and UNIQLO’s flagship store strategies.

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, consumers’ brand awareness is increased through promotion and place (location) which leads to consumers visiting the store. Moreover, product, price, and place (store) all work to heighten consumers’ brand awareness and strengthen brand association at the store, where consumers actually come into contact with the brand. Based on these factors, it can be said that the flagship store strategy, as shown in both Figure 1 and Figure 2, contributes to brand building as product, price, place (location and store), and promotion all work to heighten brand awareness and strengthen brand association.

Conclusion

In overseas markets that serve as new markets, it is important to not just make the brand known exclusively through advertising and promotions, but to build consumers’ brand awareness regarding the brand’s prices and quality, etc., and to strengthen brand association in order to achieve actual purchasing, since most of the consumers there have no experience with the brand. This is precisely why it is thought that UNIQLO is adopting a flagship store strategy, and not a strategy which depends on advertisements and promotions alone.

Since flagship stores are stores, generally speaking one could consider only the place (location/distribution) element involved in the marketing mix (4Ps) analysis, but it can be said that the differences between a normal store strategy and a flagship store strategy are not simply location and distribution. Each element of the marketing mix (4Ps), product, price, place (location and store), and promotion, is different between the two types of shops, and each element plays a role in establishing brand awareness and strengthening brand association.

It is important for flagship store strategies to contribute to strong brand building by incorporating all of these elements into the marketing mix.

Acknowledgement

This paper is financially supported by Grant-in-Aid (B) No. 18H00908 of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Conflict of Intermediates

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kapferer JN, Bastien V (2009) The luxury strategy: Break the rules of marketing to build luxury brands, Kogan Page, London, UK

- Kapferer JN (2015) Kapferer on Luxury: How Luxury Brands Can Grow Yet Remain Rare, Kogan Page, London, UK.

- Nagasawa S (2015) Brand management In: Su Mi Dahlgaard-Park (edn), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Quality and the Service Economy (book chapter), SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.39-43.

- Nagasawa S (2016) Japan has developed luxury brands. Marketing Review St. Gallen 33(5): 58-67.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2018) Flagship shop strategy for brand building: Case of UNIQLO. Proceedings of 2018 Global Marketing Conference at Tokyo, pp.1144-1156.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2019) Luxury strategy by daily fashion brand of UNIQLO: Flagship shop strategy for large store location. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 4(2): 1-6.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2020) Flagship shop strategy for brand building: Case of MUJI. Proceedings of 19th International Marketing Trends Conference (IMTC2020), Academic Research Session, Retail Strategy and Retail Brands, pp.1-17.

- Nagasawa S (2009) Premium Strategy of Local and Traditional Industries of Japan: Building Customer Experience and Technology Management. Doyukan Inc., Tokyo, pp.1-44.

- Kozinetsa RV, Sherry JF, DeBerry-Spence B, Duhachek A, Nuttavuthisit K, et al. (2002) Themed flagships brand store in the new millennium: theory, practice, prospects. Journal of Retailing 78(1): 17-29.

- Kozinetsa RV (2009) Themed flagships brand store in the new millennium: theory, practice, prospects. Kent T, Brown R (edts), ibid., pp.17-29.

- Moore CM, Doherty AM, Doyle SA (2010) Flagship stores as a market entry method: the perspective of luxury as a market entry fashion retailing. European Journal of Marketing 44(1/2): 139-161.

- Kent T, Brown R (edts) (2009) Flagship marketing: Concepts and places (Routledge Advances in Management and Business Studies), Routledge, London, p.240.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2016) The influence of social self-congruity on Japanese consumers’ luxury and non-luxury apparel brand attitudes. Luxury Research Journal 1(2): 128-149.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2017) Consumers' perceptions of store location effect on the status of luxury, non-luxury, and unknown apparel brands. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 8(1): 21-39.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2017) The effect of selective store location Strategy and self-congruity on consumers' apparel brand attitudes toward luxury vs. non-luxury. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 8(4): 266-282.

- Kumagai K, Nagasawa S (2019) Psychological switching mechanism of consumers' luxury and non-luxury brand attitude formation: The effect of store location prestige and self-congruity. Heliyon 5(5): 1-12.

- Ryohin Keikaku (2020) HP http://ryohin-keikaku.jp.

- Watanabe Y (2009) Management Reform of Mujirushi Ryohin. The Shogyokai Publishing, Tokyo pp.22-43, 60-77.

- Watanabe Y (2012) Muji: Global Strategy and Management Reform. The Shogyokai Publishing, Tokyo, Japan, pp.95-98,147-158.

- Keller KL (2007) Strategic brand management. 3rd (edn), Prentice Hall, New Jersey, USA.

-

Shin’ya Nagasawa, Norihiro Suganami. Luxury Strategy by Simple and Pleasant Life-Style Brand of MUJI — Flagship Store Strategy for Large Store Location. 6(4): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000644.

-

MUJI, Flagship store, Store location, Brand building, Luxury strategy, Apparel, UNIQLO

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Previous Studies on Flagship Stores

- Overview of Mujirushi Ryohin and MUJI

- MUJI’s Overseas Expansion

- The Marketing Mix (4Ps) Analysis of MUJI Flagship Store

- Comparison of UNIQLO’s and MUJI’s Flagship Stores

- Flagship Store Strategy Systematization

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References