Review Article

Review Article

Systematic Literature Review on Consumer Motivations Regarding Luxury

Shin’ya NAGASAWA* and Yingyu LI

Graduate School of Commerce, Waseda University, Japan

Shin’ya Nagasawa, Professor, Graduate School of Commerce, Waseda University, Japan.

Received Date:August 12, 2023; Published Date:December 22, 2023

Abstract

Purpose: The luxury industry is undergoing rapid changes owing to emerging technologies and social environments. This has resulted in

changes in consumer perceptions, motivations, and behaviors. Thus, this study aims to understand the current advances related to consumer

motivations towards luxury to advance the latest consumer profiles and behavior models in such a complex and rapidly changing context.

Design/methodology/approach: The Scopus database was thoroughly searched for academic journal articles published in English related to

consumer motivation for luxury products. A total of 141 articles were initially collected, and the abstracts of all articles were manually reviewed to

verify their relevance. Irrelevant, incomplete, or duplicate articles were excluded, resulting in 119 articles for further analysis and synthesis.

Findings: Four major themes based on research characteristics and analysis details were explored: (1) general consumer motivation, (2)

motivation of different consumer groups, (3) motivation in different luxury product or service categories, and (4) brand strategy and the brandconsumer

relationship. A holistic framework is proposed based on these themes to better understand consumer motivation in the luxury industry.

Originality: Despite several studies on consumer motivation in the luxury industry, no comprehensive analysis has synthesized the two. This

study aims to address this gap by conducting a systematic literature review.

Keywords: Luxury; Luxury Consumption; Consumer Motivation; Consumer Behavior; Systematic Literature Review

Introduction

The authors are researching the luxury strategy (Nagasawa, 2015; 2016; 2022) [1-3], especially comparing SPA brands such as UNIQLO and MUJI, and luxury brands and the flagship store strategy for large store location (Nagasawa and Suganami, 2019; 2020; 2021) [4-6].

The business environment has been continuously changing in the luxury industry, influenced by unprecedented rapid technological development and subsequent social transformation. The emergence of social media and other forms of information technology has empowered consumers with greater control over the communication of products and services. The development of global logistics and e-commerce platforms enables consumers to easily purchase online products worldwide and encourages luxury brands focus on the construction of online experiences for global consumers (Liu, Burns and Hou, 2013) [7]. Globalization and digitization have resulted in stronger competition, and COVID-19 has triggered sudden global changes in business environments in recent years.

To address the challenges brought about by the changing business environment, luxury brands must understand consumer motivations thoroughly. This is because the motivations of consumers influence their actual behaviors in communicating with luxury brands and purchasing luxury products and services. Only when luxury brands understand consumers well can they adopt appropriate marketing strategies to satisfy the consumer needs and motivate them to engage with brands and purchase products (Yi-Cheon Yim, et al, 2014) [8]. Thus, researchers must understand the current advances in the literature on consumer motivation to advance the latest consumer profiles and behavioral models in a complex and rapidly changing context. Abundant research has focused on motivation to purchase luxury products or services; however, a comprehensive review is lacking. To fill this research gap, this study collects and synthesizes extant studies on consumer motivations in the luxury context.

This paper begins with a brief introduction to the academic background on luxury and consumer motivation. Subsequently, the methodology used to conduct the literature review and the process of article collection and synthesis are described. The results provided an analysis of article characteristics and a categorization of four themes: general consumer motivation, motivation of different consumer groups, motivation in different product or service categories, brand strategy, and brand-consumer relationship. Finally, this paper provides implications for future research and offers concise conclusions.

Literature Review

Luxury and luxury consumption

Scholars have not yet reached a clear consensus on the definition of luxury up to the present time (Ko, Costello and Taylor, 2019) [9], as it varies in different contexts. However, it is widely acknowledged that the understanding of “luxury” is subjective and depends on the perspective of consumers (Phau and Prendergast, 2000) [10]. Consumers can choose luxury purchases to satisfy their needs for different values, including conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values (Vigneron and Johnson, 1999) [11]. Since Veblen’s (1899) [12] initial concept of conspicuous consumption, luxury consumption has been closely associated with conspicuous consumption as consumers tend to use it to display their wealth and social status. However, later research indicated that status and conspicuous consumptions are distinct constructs (O’Cass and McEwen, 2004)[13]. In status consumption, consumers can possess products with status signals but do not publicly display the products. In contrast, consumers intentionally display certain signals to gain social status through conspicuous consumption. Considering the differences in status and conspicuous consumptions, scholars (Berger and Ward, 2010 [14]; Eckhardt, et al., 2015 [15]) have identified the concept of inconspicuous consumption and the trends of inconspicuous consumption behaviors in the context of luxury. Evidently, conspicuous luxury products can demonstrate consumer status to the public; however, the consumers’ motivations for choosing inconspicuous luxury products are still worth further study. Shao, et al. (2019a, 2019b) [16, 17] explored the relationship between intrinsic motivation and inconspicuous luxury consumption as well as the moderating role of consumer personality and behavior. Owing to the increasing trend of inconspicuous consumption, additional empirical investigations must be conducted to redefine the understanding of luxury and the practices associated with luxury consumption. As more research is dedicated to examining the various subdivided forms of luxury consumption, it is crucial to delve deeper into the existing luxury consumption landscape and the factors shaping it.

Consumer motivation in luxury

Consumer motivation in luxury is a broad topic includes motivations to consume luxury products and to engage with various marketing activities of luxury brands. According to Ryan and Deci Ryan and Deci (2000) [18], motivations are categorized for different reasons or goals that drive specific actions. The most basic distinction is between intrinsic motivation, wherein individuals engage in an activity because they find it inherently interesting or enjoyable, and extrinsic motivation, wherein individuals participate in an activity because it results in a separate outcome Ryan and Deci (2000) [18]. Roy, et al. (2018) [19] note that consumers’ motivations for luxury consumption are primarily influenced by their inner thoughts and emotions. Thus, the consumers’ motivation to engage in luxury consumption can differ based on various factors such as demographics, socioeconomic background, and cultural norms. Purchasing luxury products satisfies various social and personal needs of consumers, such as presenting a specific social class, communicating a desired self-image, and providing self-concept reinforcement (Nia and Zaichkowsky, 2000) [20]. Meanwhile, consumers are increasingly motivated by recreational and experiential factors rather than simply buying and possessing goods (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2017) [21]. Bazi et al. (2020) [22] identified six macro-dimensions of consumer motivations for engaging with luxury brands on social media: perceived content relevancy (brand news, post quality, and celebrity endorsement), brandcustomer relationship (brand love and brand ethereality), hedonic (entertainment), aesthetic (design appeal), socio-psychological (actual self-congruency, status signaling, and enhanced and maintained face), brand equity (perceived brand quality), and technology factors (ease of use and convenience). For luxury brands, it is important to gain a comprehensive understanding of the factors that affect consumer motivation, particularly within a specific product or service category.

Approach to the Review

The approach used in this study involved a systematic review (Tranfield, et al., 2003 [23]; Latif, et al., 2018 [24]), which entailed collecting, analyzing, and synthesizing all relevant papers related to consumer motivation for luxury.

The data collection strategy comprised two stages. First, the Scopus database was searched at the end of May in 2023 by using < ‘luxury’ AND ‘consumer motivation’ > within the title, abstract, and keyword fields. The search was initiated using two broad terms to ensure that an adequate number of relevant articles were included. Additional filters were then applied to limit the search results to academic journal articles published in English, while excluding books, book chapters, and conference papers. A timeframe was applied to limit the articles to the final stage of publication. Based on these criteria, 141 articles were selected.

Following the initial search, the abstracts of all articles were manually reviewed to verify their relevance. This study only included articles with objectives aimed at examining consumer motivation in the context of luxury. Twenty-two articles were excluded owing to irrelevance, incompleteness, or duplication, resulting in 119 articles for further scrutiny.

Results

To conclude the articles’ characteristics and common themes, each literature was precisely analyzed based on the content. The results of this study are divided into three sections: descriptive characteristics, methodological characteristics, and thematic analysis.

Descriptive characteristics

Based on the Scopus classification, the collected articles were categorized under 14 disciplines. The most studied research fields are “Business, Management, and Accounting” (105 publications), “Economics, Econometrics, and Finance” (17), “Social Sciences” (17), and “Psychology” (9). Certain articles simultaneously belonged to multiple disciplines. The key academic journals in this sample are the Journal of Business Research (14), Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management (11), Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services (10 records), and Journal of Consumer Marketing (7).

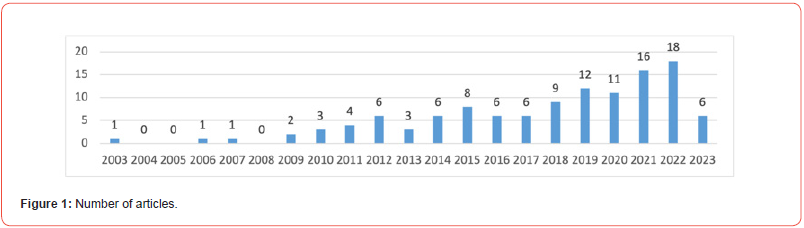

Upon the analysis of publications per year, very few articles related to this topic were found to be published before 2009, with only one article being published in each of the three years 2003, 2006, and 2007. The number of articles fluctuated between 2009– 2016, within a range of 2–8 articles per year. A steady increase in the number of articles has been observed since 2017. Although one fewer article was published in 2020 than in 2019, the number of articles remained high. A surge from 11 to 16 articles was observed from 2020 to 2021, whereas the increase slowed from 2021 to 2022, with a growth of only two articles. As the number of articles in 2023 only included articles published before the end of May, the data were incomplete (Figure 1).

Methodological characteristics

In terms of methodology, the sample was examined in terms of research type, research design, and analysis techniques. The majority (63.87%, 76 out of 119) of the studies were conducted as quantitative research. Thirty papers applied a qualitative approach, and 10 papers applied both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Only three studies used the review approach as their primary research type.

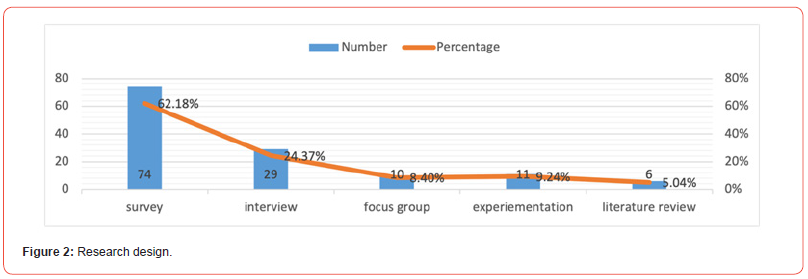

The most used research design was surveys, which was employed in 74 articles (62.18%), followed by interviews (29, 24.37%), experiments (11, 9.24%), focus groups (10, 8.40%), and literature reviews (6, 5.04%). Of these, 21 employed multiple research designs (Figure 2).

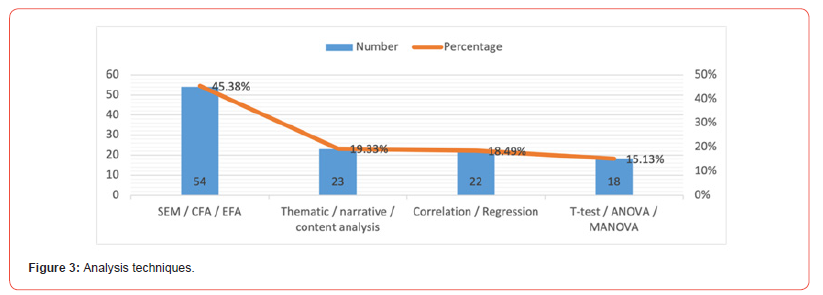

Analytical techniques are grouped into several major categories. Structural equation modeling (SEM), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) composed the most commonly used techniques and were applied in 54 articles. Qualitative analysis methods (23), which mainly included thematic, narrative, and content analyses, were the second most used group. The next was the correlation or regression group (22). The last major group was the t-test, ANOVA or MANOVA (18) (Figure 3).

Theme analysis

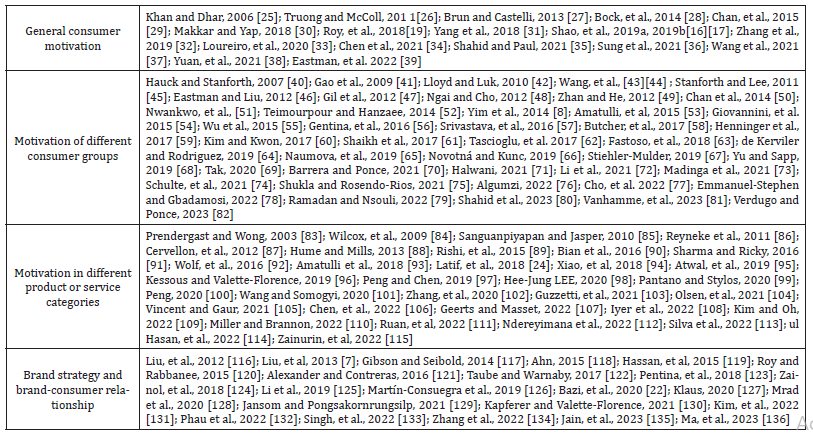

Within the context of consumer motivation towards luxury, four themes were identified in the review process. The categorization criteria were based on the research topic of each article. The articles related to the first theme focused on the general consumer motivations towards luxury consumption shared by different consumer groups and luxury categories. In case of the second theme, the articles analyzed the variation in motivations in different consumer groups. For the third theme, the divergence of consumer motivations for different product or service categories was scrutinized. Finally, for the last theme, the articles were focused on the influence of brand strategy on consumer motivations and the relationships between brands and consumer motivations within the luxury context (Table 1).

Table 1:Studies categorized in different themes.

General consumer motivation: Studies on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation form the basis of research on consumer motivation towards luxury purchases. Seven of the 18 articles in this category investigated consumers’ intrinsic motivations for luxury consumption. The most commonly studied intrinsic factors are self-concept, need for uniqueness, and self-expansion Shao, et al., 2019b, 2019a [16, 17]; Khan and Dhar, 2006 [25]; Truong and McColl, 2011 [26]; Brun and Castelli, 2013 [27]; Chen et al., 2021 [34]; Barrera and Ponce, 2021 [70]).

Eight studies explored consumer motivation in relation to status consumption, interpersonal relationships, and other social factors. These studies have investigated topics such as social comparison, social adjustive attitudes, and symbolic consumption (Shao et al., 2019a, 2019b [16, 17]; Brun and Castelli, 2016 [27]; Elizabeth-Bock et al., 2014 [28]; Chan et al., 2015 [29]; Zhang et al., 2019 [32]; Chen et al., 2021 [34]; Wang et al., 2021 [37]).

Since Veblen’s (1899) [12] study on conspicuous consumption, extrinsic value has been recognized as a major motivation for purchasing luxury products. Recently, the similarities and differences between conspicuous and luxury consumptions have been clarified (Yuan et al., 2021) [38]. Shahid and Paul (2021) [35] found that consumers gradually become intrinsically driven by luxury consumption. The increasing recognition of subtle or inconspicuous luxury consumption in luxury research necessitates further exploration of the motivations towards it (Eastman et al., 2022) [39]. Eastman, et al. (2022) [39] defined and developed a measure of inconspicuous luxury motivations with nine items based on two factors: intrinsic motivation to enjoy privacy in luxury consumption and extrinsic motivation to be associated with the experienced luxury elite.

A few studies have examined other factors affecting consumer behavior in the luxury consumption context, such as envy (Loureiro et al., 2020) [33] and narcissism (Fastoso et al., 2018) [63]. Certain studies focused on this aspect have been conducted on a certain group of consumers; however, they did not focus on the characteristics of specific consumer groups. Therefore, they belong to the first theme instead of the second theme, focusing on consumer segmentation. Rather than focusing solely on a specific target group, these studies investigated overall consumer traits. It would be valuable to broaden the research scope to a larger group of consumers based on the findings of these studies obtained from a certain group of consumers.

Motivation of different consumer groups: As the most frequently studied theme, several studies (44 articles) were conducted on a specific group of consumers based on demographic factors (e.g., age, generation, and gender), cultural and geographical factors (e.g., district, country, and religion), or specific behaviors (e.g., purchasing luxury goods during tourism).

In terms of age groups, young consumers, such as Generation Y, have been an emergent segment of the luxury market (Giovannini, et al., 2015) [54] and this age group is the most frequently studied objective (with six articles). Luxury brands provide Generation Y consumers with conspicuous or hedonic values along with opportunities for self-expansion and self-growth (de Kerviler and Rodriguez, 2019 [64]; Tak, 2020 [69]). Within this age group, it is also found that conspicuous motivations (both bandwagon and snob motivations) were more prominent in men than in women (Verdugo and Ponce, 2023) [82]. The comparison of different age cohorts’ motivations (Hauck and Stanforth, 2007; Eastman and Liu, 2012; Halwani, 2021) [40,46,71] is another popular topic (with three articles) that can provide practical implications for luxury brands to better target their consumers based on age. In addition to the above topics, other age groups, such as Generation Z, teenagers, young adults, and older consumers, have also attracted research interest (Gil et al., 2012 [47]; Amatulli, et al., 2015 [53]; Barrera and Ponce, 2021 [70]; Cho, et al., 2022 [77]).

Regarding individual luxury markets, China (13 articles), the U.S. (5 articles), and India (3 articles) were the most studied. With its large population and fast-growing economy, China has become the most prominent market, attracting the interests of managers and researchers. The comparison of different markets mainly focuses on the difference between mature and emergent markets or collectivistic and individualistic cultures (Shaikh et al., 2017 [61]; Yu and Sapp, 2019 [68]). The study by Naumova et al. (2019) [65] found that consumers from cultures with high collectivism primarily perceive social values in consuming luxury goods and are sensitive to conspicuous luxury. In contrast, consumers from cultures with high individualism perceive individual and functional values and are sensitive to hedonistic luxury.

Within the tourist context, Chan et al., (2014) [50] examined the impact of intrinsic factors on the purchasing behavior of Chinese consumers in other luxury markets. The results revealed four key attributes (self-satisfaction, possession obsessiveness, status consciousness, and personal differentness), as well as three distinct consumer segments (“shopping hedonists,” “ego-defended achievers,” and “conspicuous fashionistas”). Li, et al. (2021) [72] delved deeper into the connection between self-concept and luxury shopping behavior among tourists and investigated the sociopsychological aspects involved, including the motivations behind their purchases and how these purchases relate to their self-perception during holidays.

Motivation in different product or service categories: Studies focusing on motivation towards a distinctive product or service category comprised 28.57% (34 out of 119) of all the studies. Within this theme, the hospitality industry (11), collaborative consumption (10), and counterfeit products (7) were the most studied.

In studies related to the hospitality industry, consumers’ motivations and perceived risks towards sustainable operations in regard of hotel and restaurant services have been explored (Rishi et al., 2015 [89]; Peng and Chen, 2019 [97]; Peng, 2020 [100]). The focus on sustainable luxury has led to increased interest in these studies, which offer valuable insights into the factors that encourage or deter consumers from engaging in environmentally friendly behaviors (Rishi et al., 2015 [89]; Peng and Chen, 2019 [97]; Peng, 2020 [100]). Consumer perceptions and motivations for luxury wine consumption, particularly for luxury wines as gifts, have also been explored (Reyneke et al., 2011 [86]; Wolf et al., 2016 [92]). Wolf et al. (2016) [92] found that luxury wine consumption must be congruent with consumers’ self-identity and their reference or aspirational groups’ perceived norms.

In the collaborative luxury consumption, vintage products, second-hand products, and rental services were explored to understand consumer motivations in unconventional categories (Guzzetti et al., 2021) [103].

Vintage products provide consumer satisfaction with individual identity, improved self-confidence, and achievement as a sense of fulfillment (Amatulli et al., 2018) [93]. Second-hand products enable consumers to link social climbing, eco-conscious concerns, brand heritage, and windfalls (Kessous and Valette-Florence, 2019) [96]. Compared to other product categories, bargain hunting, treasury hunting, and individuality are specific motivators for second-hand luxury consumption (Silva et al., 2022) [113]. Consumers’ choice of rental services is primarily driven by utilitarian reasons (Guzzetti et al., 2021) [103].

Social functions are generally recognized as the primary factor affecting consumer attitudes towards counterfeit consumption (Wilcox et al., 2009 [84]; Xiao et al., 2018 [94]). Bian et al. (2016) [90] clarified the psychological and emotional factors that drive and result from the consumption of counterfeit products. Xiao et al. (2018) [94] investigated how self-monitoring and perceived social risk moderate the effect of actual-ideal self-discrepancy on consumer attitudes towards counterfeit branded luxuries. Iyer et al. (2022) [108] explored the moderating effect of interpersonal influence on consumer attitudes towards authentic and counterfeit luxury products.

Brand strategy and brand-consumer relationship: Of the four themes, brand strategy and brand-consumer relationships received comparatively less attention, being the second least explored theme (23 articles). Self-congruity, which refers to the relationship between a consumer’s self-image and the brand image, is a crucial topic in this field field. Roy and Rabbanee (2015) [120] found that self-congruity with a luxury brand enhances consumers’ self-perceptions and is positively influenced by social desirability, need for uniqueness, and status consumption. Li, et al. (2019) [125] identified that higher class consumers often focus more on the intrinsic value of a brand to express their self-identity, resulting in a higher self-brand association. Consequently, these consumers tend to favor inconspicuous consumption because there is a strong connection between their self-image and the brand image. Zhang et al. (2022) [134] examined the influence of the discrepancy between consumers’ actual and ideal self-congruity on their subjective wellbeing after a purchase.

Several brand strategies and their corresponding influences on consumers have been discussed, such as corporate social responsibility (Ahn, 2015) [118], inter-industry creative collaboration (Alexander and Contreras, 2016) [121], pop-up retailing (Taube and Warnaby, 2017) [122], brand globalness (Hassan et al., 2015) [119], pricing (Kapferer and Valette-Florence, 2021) [130], and return policies within an e-commerce context (Phau et al., 2022) [132]. Previous studies have widely accepted that luxury brands prefer lifestyle advertisements to functional advertisements. However, Ma et al. (2023) [136] found that functional advertisements could be more effective than lifestyle advertisements for luxury products in specific situations such as the purchase decision-making stage.

Recent research on this topic has focused on digitization, particularly in social media marketing and online retailing. Liu et al. (2013) [7] and Klaus (2020) [127] focused on the differences in consumer motivation towards online and offline luxury consumption. The in-store experience has always been crucial for fulfilling consumers’ expectations of luxury quality and experience, and the online experience is becoming increasingly influential. Klaus (2020) [127] explored consumer motivations expected and received from online luxury experiences (OLX). Consumers’ motivations for engaging with luxury brands on social media have also been explored in many studies. Martín-Consuegra et al. (2019) [126] analyzed the relationship between brand involvement, consumer-brand interaction, and behavioral intention in the context of luxury brand-related activities on social media. Jansom and Pongsakornrungsilp (2021) [129] studied the role of influencers in marketing in relation to consumer motivations for luxury purchasing. As indicated by Pentina et al. (2018) [123], consumer engagement behaviors have different potentials for luxury brand co-creation on social media. In addition to social media marketing, Jain et al. (2023) [135] studied digitization for gamification. The association between the motivation to adopt gamification, customer engagement, and affective commitment has been investigated for luxury consumers and brands.

Future Research Agenda

Despite the increasing number of publications focusing on consumer motivations for luxury consumption (Figure 1), there remain several research gaps that require further exploration. The following topics within each theme are proposed for future research to expand our understanding of consumer motivations in the luxury context.

General consumer motivations: intrinsic value and subtle signals

Previous research has investigated the link between brand visibility and consumer motivation in the luxury context (Berger and Ward, 2010) [14]. The findings highlight that consumers purchase luxury brands to construct a desirable self-concept by communicating central beliefs, attitudes, and values to others (self-expressive) or, alternatively, gain approval in social situations (social-adjustive). Shao et al. (2019b) [17] found an interesting result in their research that consumer motivation (extrinsic versus intrinsic) does not directly influence the consumers’ preferences for brand visibility (explicit versus subtle). However, the role of individual differences such as personality traits, self-concept, and cultural values in moderating the relationship between motivation and brand visibility preference requires further investigation. Further scrutiny of the relationship between consumers’ intrinsic motivations and subtly marked luxury brands could provide meaningful implications for designing strategies in the luxury industry.

Simultaneously, Chinese consumers have been suggested to purchase luxury goods to fulfil their functional and social needs (Lloyd and Luk, 2010) [42]. This is consistent with Naumova et al. (2019) [65], who found that consumers from cultures with high collectivism mainly perceive social values with luxury consumption. Following several years of luxury brand development in emerging markets and the accumulation of consumer knowledge of luxury products, the recent study of Li et al. (2021) [72] revealed a new trend wherein the concept of individuality begins to influence Chinese consumers’ luxury purchases. Therefore, future research can explore consumer motivations related with intrinsic values in emerging luxury markets as well.

Motivation of different consumer groups: inter and intra-country difference

Luxury brands have expanded globally in the process of globalization. Therefore, understanding consumers from different cultural backgrounds contributes to the growth of the luxury sector. As concluded in the second theme (motivation of different consumer groups), cultural differences, particularly for consumers in different countries, have become a popular topic in the extant literature.

However, current research assumes that consumers within a country have similar thoughts and behaviors without considering intra-country differences (Shukla and Rosendo-Rios, 2021) [75]. It would be valuable to delve deeper into the nuances of cultural differences within specific markets, moving beyond broad comparisons between mature and emergent markets or collectivistic and individualistic cultures As research on luxury consumption matures, it is important to segment consumer groups within a country for future research, particularly in major markets such as China, the U.S., and India. In countries with large populations and vast territories, there are significant intra-country differences in consumer motivation and behavior that require further research (Shukla and Rosendo-Rios, 2021) [75]. Furthermore, it would also be interesting to expand the focus beyond the most-studied luxury markets (China, the U.S., and India) and explore other diverse markets to gain a more comprehensive understanding of consumer motivations in different cultural contexts. By investigating markets that have received less attention, researchers can uncover unique insights and explore how consumer motivation varies across regions and countries.

Motivation in different product or service categories: from luxury product to experience

In the third theme (motivation for different product or service categories), the tangible aspects of luxury goods remain the primary focus, and luxury experiences are less discussed (Hemetsberger, 2012) [137]. According to de Kerviler and Rodriguez (2019) [64], consumers consume luxury in the pursuit of materialism and in the search for enrichment through experiences. In the luxury hospitality field, consumers are concerned about the sustainability practices of luxury restaurants, which they believe may introduce a perceived risk to their dining experiences (Peng and Chen, 2019) [97]. It would be meaningful to examine how consumers’ perceptions of sustainability initiatives and their experiences with sustainable luxury hotels and restaurants influence their attitudes, behaviors, and satisfaction. Another topic worth investigating is the effectiveness of the various communication and marketing strategies employed by luxury hospitality brands to promote sustainable initiatives and enhance consumer experience.

Regarding collaborative consumption, the consumption of vintage and secondhand luxury items is also an experience for consumers to indulge in fantasies and feel the excitement linked to an unpredictable shopping activity (Guzzetti et al., 2021) [103]. Understanding the experiential factors that drive consumer engagement in these categories, such as the emotional and sensory aspects of collaborative consumption, can contribute to a deeper understanding of consumer behavior. Furthermore, considering the importance of luxury experiences in enhancing consumer motivation and engagement, it would be interesting to expand research on the impact of ambiance, personalized services, and immersive environments on consumer perceptions and behaviors in different product or service categories.

Brand strategy and brand-consumer relationship: social media marketing and online shopping

Research on brand strategies that influence consumer motivation remains underdeveloped. With the increasing usage of digital technology, consumers have more control over the information of consumption through social media platforms. However, the current literature on online and offline luxury retailing (Liu et al. 2020 [7]; Klaus, 2013 [127]) is insufficient for luxury brands to build a seamless luxury experience for consumers to switch smoothly between online and offline experiences. Future research in the luxury industry should focus on exploring the dynamic influence of digital technologies on the brand-consumer relationship. Specifically, there is a need to investigate how luxury brands can effectively utilize social media platforms to engage and influence consumers in their luxury consumption journey. This includes examining the impact of influencer marketing strategies, user-generated contents, and interactive features on consumer attitudes, perceptions, and purchasing behaviors. Understanding the roles of personalization, customization, and virtual shopping experiences in a luxury context is also crucial. Moreover, future research should delve into the challenges and opportunities presented by emerging technologies such as augmented reality and virtual reality in enhancing luxury online shopping experiences. By addressing these research gaps, valuable insights can be gained to aid in constructing luxury brand strategies to create a seamless and engaging luxury consumer journey.

Conclusion

Researchers continue to explore why consumers are motivated to buy luxury products in various contexts. This study concluded that four themes are necessary to understand the distinctive research paths in this field and provided advice on future research paths. While categories of values motivating consumers, typologies of consumer groups, variations in luxury industries, and effective brand strategies have been widely explored in the extant literature, the business context and consumer characteristics have faced fierce competitiveness and dramatic changes, particularly under the global influence of COVID-19 in recent years. Furthermore, the rise of alternative communication and consumption modes compared with traditional ones poses challenges in understanding the transformation in consumer motivation towards luxury consumption.

Acknowledgement

This research project was sponsored by Waseda University.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nagasawa N (2015) Brand Management’, Dahlgaard-Park S.-M. (edt) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Quality and the Service Economy (Book Chapter), SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.39–43.

- Nagasawa N (2016) Japan Has Developed Luxury Brands. Marketing Review St. Gallen 33(5): 58-67.

- Nagasawa N (2022) Montblanc's Entrepreneurship from Pens to Watches and Social Contribution through the Art of "Writing". Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 10(1): 1-7.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2019) Luxury strategy by daily fashion brand of UNIQLO: Flagship shop strategy for large store location. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 4(2): 1–6.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2020) Luxury strategy by simple and pleasant life-style brand of MUJI: Flagship store strategy for large store location. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 6(4): 1-7.

- Nagasawa S, Suganami N (2021) Luxury strategy comparing SPA brands and luxury brands: Flagship store strategy for large store location. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 7(3): 1-8.

- Liu X, Burns A, Hou Y (2013) Comparing online and in-store shopping behavior towards luxury goods. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41: 885-900.

- Yim, MYC, Sauer PL, Williams J, Lee SJ, Macrury I (2014) Drivers of attitudes toward luxury brands: A cross-national investigation into the roles of interpersonal influence and brand consciousness. International Marketing Review 31(4): 363-389.

- Ko E, Costello JP, Taylor CR (2019) What is a luxury brand? A new definition and review of the literature. Journal of Business Research 99: 405-413.

- Phau I, Prendergast G (2000) Consuming luxury brands: The relevance of the ‘Rarity Principle’. Journal of Brand Management 8: 122–138.

- Vigneron F, Johnson LW (1999) A Review and a Conceptual Framework of Prestige-Seeking Consumer Behavior. Academy of Marketing Science Review 1(1); 17.

- Veblen T (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class. Penguin, New York, USA.

- O’Cass A, McEwen H (2004) Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 4(1): 25-39.

- Berger J, Ward M (2010) Subtle Signals of Inconspicuous Consumption. Journal of Consumer Research 37(4): 555-569.

- Eckhardt GM, Belk RW, Wilson JAJ (2015) The rise of inconspicuous consumption. Journal of Marketing Management 31(7-8): 807-826.

- Shao W, Grace D, Ross M (2019a) Consumer motivation and luxury consumption: Testing moderating effects. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 46: 33-44.

- Shao W, Grace D, Ross M (2019b) Investigating brand visibility in luxury consumption. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49: 357-370.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25(1): 54-67.

- Roy S, Jain V, Matta N (2018) An integrated model of luxury fashion consumption: perspective from a developing nation. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 22(1): 49-66.

- Nia A, Zaichkowsky JL (2000) Do counterfeits devalue the ownership of luxury brands? Journal of Product & Brand Management 9(7): 485-497.

- Bardhi F, Eckhardt GM (2017) Liquid Consumption. Journal of Consumer Research 44(3): 582-597.

- Bazi S, Filieri R, Gorton M (2020) Customers’ motivation to engage with luxury brands on social media. Journal of Business Research 112: 223-235.

- Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 14(3): 207-222.

- Latif ÖB, Yiğit MK (2018) A review of counterfeiting research on demand side: Analyzing prior progress and identifying future directions. The Journal of World Intellectual Property 21(5-6): 458-480.

- Khan U, Dhar R (2006) Licensing Effect in Consumer Choice. Journal of Marketing Research 43(2): 259-266.

- Truong Y, McColl R (2011) Intrinsic motivations, self-esteem, and luxury goods consumption. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 18(6): 555-561.

- Brun A, Castelli C (2013) The nature of luxury: a consumer perspective. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41(11/12): 823-847.

- Bock DE, Eastman JK (2014) The impact of economic perceptions on status consumption: an exploratory study of the moderating role of education. Journal of Consumer Marketing 31(2): 111-117.

- Chan WY, To CKM, Chu WC (2015) Materialistic consumers who seek unique products: How does their need for status and their affective response facilitate the repurchase intention of luxury goods? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 27: 1-10.

- Makkar M, Yap SF (2018) The anatomy of the inconspicuous luxury fashion experience. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 22(1): 129-156.

- Yang J, Ma J, Arnold M, Nuttavuthisit K (2018) Global identity, perceptions of luxury value and consumer purchase intention: a cross-cultural examination. Journal of Consumer Marketing 35(5): 533-542.

- Zhang W, Jin J, Wang A, Ma Q, Yu H (2019) Consumers’ Implicit Motivation of Purchasing Luxury Brands: An EEG Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag 12: 913-929.

- Loureiro SMC, de Plaza MAP, Taghian M (2020) The effect of benign and malicious envies on desire to buy luxury fashion items. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 52: 101688.

- Chen M, Zhang J, Xie Z, Niu J (2021) Online low‐key conspicuous behavior of fashion luxury goods: The antecedents and its impact on consumer happiness. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 20(1): 148-159.

- Shahid S, Paul J (2021) Intrinsic motivation of luxury consumers in an emerging market. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 61: 102531.

- Sung B, Hatton-Jones S, Teah M, Cheah I, Phau I (2021) Shelf-based scarcity as a cue of luxuriousness: an application of psychophysiology. European Journal of Marketing 55(2): 497-516.

- Wang W, Chen N, Li J, Sun G (2021) SNS use leads to luxury brand consumption: evidence from China. Journal of Consumer Marketing 38(1): 101-112.

- Yuan W, Gong S, Gao J (2021) How Does House Demolition Affect Family Conspicuous Consumption? Frontiers in Psychology 12: 741006.

- Eastman JK, Iyer R, Babin B (2022) Luxury not for the masses: Measuring inconspicuous luxury motivations. Journal of Business Research 145: 509-523.

- Hauck WE, Stanforth N (2007) Cohort perception of luxury goods and services. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 11(2): 175-188.

- Gao L, Norton MJT, Zhang Z, Kin‐man To C (2009) Potential niche markets for luxury fashion goods in China. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 13(4): 514-526.

- Lloyd AE, Luk STK (2010) The Devil Wears Prada or Zara: A Revelation into Customer Perceived Value of Luxury and Mass Fashion Brands. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 1(3): 129-141.

- Wang Y, Sun S, Song Y (2010) Motivation for luxury consumption: Evidence from a metropolitan city in China, Belk RW (ed.) Research in Consumer Behavior. Emerald Group Publishing Limited: 161-181.

- Wang Y, Sun S, Song Y (2011) Chinese Luxury Consumers: Motivation, Attitude and Behavior. Journal of Promotion Management 17(3): 345-359.

- Stanforth N, Lee SH (2011) Luxury Perceptions: A Comparison of Korean and American Consumers. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 2(2): 95-103.

- Eastman JK, Liu J (2012) The impact of generational cohorts on status consumption: an exploratory look at generational cohort and demographics on status consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29(2): 93-102.

- Gil LA, Kwon K-N, Good LK, Johnson LW (2012) Impact of self on attitudes toward luxury brands among teens. Journal of Business Research 65(10): 1425-1433.

- Ngai J, Cho E (2012) The young luxury consumers in China. Young Consumers 13(3): 255-266.

- Zhan L, He Y (2012) Understanding luxury consumption in China: Consumer perceptions of best-known brands. Journal of Business Research 65(10): 1452-1460.

- Chan WWY, To CKM, Chu AWC, Zhang Z (2014) Behavioral Determinants that Drive Luxury Goods Consumption: A Study within the Tourist Context. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 18(2): 84-95.

- Nwankwo S, Hamelin N, Khaled M (2014) Consumer values, motivation and purchase intention for luxury goods. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21(5): 735-744.

- Teimourpour B, Hanzaee KH (2014) An analysis of Muslims’ luxury market in Iran. Journal of Islamic Marketing 5(2): 198-209.

- Amatulli C, Guido G, Nataraajan R (2015) Luxury purchasing among older consumers: exploring inferences about cognitive Age, status, and style motivations. Journal of Business Research 68(9): 1945-1952.

- Giovannini S, Xu Y, Thomas J (2015) Luxury fashion consumption and Generation Y consumers: Self, brand consciousness, and consumption motivations. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 19(1): 22-40.

- Wu M.-S.S, Chaney I, Steve Chen C-H, Nguyen B, Melewar TC (2015) Luxury fashion brands: Factors influencing young female consumers’ luxury fashion purchasing in Taiwan. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 18(3): 298-319.

- Gentina E, Shrum LJ, Lowrey TM (2016) Teen attitudes toward luxury fashion brands from a social identity perspective: A cross-cultural study of French and U.S. teenagers. Journal of Business Research 69(12): 5785-5792.

- Srivastava RK, Bhanot S, Srinivasan R (2016) Segmenting Markets Along Multiple Dimensions of Luxury Value: The Case of India. Journal of Promotion Management 22(1): 175-193.

- Butcher L, Phau I, Shimul AS (2017) Uniqueness and status consumption in Generation Y consumers: Does moderation exist?. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 35(5): 673-687.

- Henninger CE, Alevizou PJ, Tan J, Huang Q, Ryding D (2017) Consumption strategies and motivations of Chinese consumers: The case of UK sustainable luxury fashion. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 21(3): 419-434.

- Kim HY, Kwon YJ (2017) Blurring production-consumption boundaries: Making my own luxury bag. Journal of Business Research 74: 120-125.

- Shaikh S, Malik A, Akram MS, Chakrabarti R (2017) Do luxury brands successfully entice consumers? The role of bandwagon effect. International Marketing Review 34(4): 498-513.

- Tascioglu M, Eastman JK, Iyer R (2017) The impact of the motivation for status on consumers’ perceptions of retailer sustainability: the moderating impact of collectivism and materialism. Journal of Consumer Marketing 34(4): 292-305.

- Fastoso F, Bartikowski B, Wang S (2018) The “little emperor” and the luxury brand: How overt and covert narcissism affect brand loyalty and proneness to buy counterfeits. Psychology & Marketing 35(7): 522-532.

- de Kerviler G, Rodriguez CM (2019) Luxury brand experiences and relationship quality for Millennials: The role of self-expansion. Journal of Business Research 102: 250-262.

- Naumova O, Bilan S, Naumova M (2019) Luxury consumers’ behavior: a cross-cultural aspect. Innovative Marketing 15(4): 1-13.

- Novotná M, Kunc J (2019) Luxury tourists and their preferences: Perspectives in the Czech Republic 67(1): 90-96.

- Stiehler-Mulder BE (2019) The application of DICTION to analyze qualitative data: A luxury brand perspective. Acta Commercii 19(1).

- Yu D, Sapp S (2019) Motivations of Luxury Clothing Consumption in the U.S. vs. China. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 31(2): 115-129.

- Tak P (2020) Antecedents of Luxury Brand Consumption: An Emerging Market Context. Asian Journal of Business Research 10(2).

- Barrera GA, Ponce HR (2021) Personality traits influencing young adults’ conspicuous consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45(3): 335-349.

- Halwani L (2021) Heritage luxury brands: insight into consumer motivations across different age groups. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 24(2): 161-179.

- Li CS, Zhang CX, Chen X, Wu MSS (2021) Luxury shopping tourism: views from Chinese post-1990s female tourists. Tourism Review 76(2): 427-438.

- Madinga NW, Maziriri ET, Chuchu T, Mototo L (2021) The LGBTQAI+ community and luxury brands : exploring drivers of luxury consumption in South Africa. African Journal of Business and Economic Research 16(1): 207-225.

- Schulte M, Balasubramanian S, Paris CM (2021) Blood Diamonds and Ethical Consumerism: An Empirical Investigation. Sustainability 13(8): 4558.

- Shukla P, Rosendo-Rios V (2021) Intra and inter-country comparative effects of symbolic motivations on luxury purchase intentions in emerging markets. International Business Review 30(1): 101768.

- Algumzi A (2022) Factors Influencing Saudi Young Female Consumers’ Luxury Fashion in Saudi Arabia: Predeterminants of Culture and Lifestyles in Neom City. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15(7): 274.

- Cho E, Kim-Vick J, Yu U.-J (2022) Unveiling motivation for luxury fashion purchase among Gen Z consumers: need for uniqueness versus bandwagon effect. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 15(1): 24-34.

- Emmanuel-Stephen CM, Gbadamosi A (2022) Hedonism and luxury fashion consumption among Black African women in the UK: an empirical study. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 26(1): 126-140.

- Ramadan Z, Nsouli NZ (2022) Luxury fashion start-up brands’ digital strategies with female Gen Y in the Middle East. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 26(2): 247-265.

- Shahid S, Islam JU, Farooqi R, Thomas G (2023) Affordable luxury consumption: an emerging market’s perspective. International Journal of Emerging Markets 18(2): 316-336.

- Vanhamme J, Lindgreen A, Sarial-Abi G (2023) Luxury Ethical Consumers: Who Are They? Journal of Business Ethics 183(3): 805-838.

- Verdugo GB, Ponce HR (2023) Gender Differences in Millennial Consumers of Latin America Associated with Conspicuous Consumption of New Luxury Goods. Global Business Review 24(2): 229-242.

- Prendergast G, Wong C (2003) Parental influence on the purchase of luxury brands of infant apparel: an exploratory study in Hong Kong. Journal of Consumer Marketing 20(2): 157-169.

- Wilcox K, Kim HM, Sen S (2009) Why Do Consumers Buy Counterfeit Luxury Brands? Journal of Marketing Research 46(2): 247-259.

- Sanguanpiyapan T, Jasper C (2010) Consumer insights into luxury goods: Why they shop where they do in a jewelry shopping setting. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 17(2): 152-160.

- Reyneke M, Berthon PR, Pitt LF, Parent M (2011) Luxury wine brands as gifts: ontological and aesthetic perspectives. International Journal of Wine Business Research 23(3): 258-270.

- Cervellon M, Carey L, Harms T (2012) Something old, something used: Determinants of women’s purchase of vintage fashion vs second‐hand fashion. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 40(12): 956-974.

- Hume M, Mills M (2013) Uncovering Victoria’s Secret: Exploring women’s luxury perceptions of intimate apparel and purchasing behavior. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 17(4): 460-485.

- Rishi M, Jauhari V, Joshi G (2015) Marketing sustainability in the luxury lodging industry: a thematic analysis of preferences amongst the Indian transition generation. Journal of Consumer Marketing 32(5): 16.

- Bian X, Wang K-Y, Smith A, Yannopoulou N (2016) New insights into unethical counterfeit consumption. Journal of Business Research 69(10): 4249-4258.

- Sharma P, Ricky YKC (2016) Demystifying deliberate counterfeit purchase behaviour: towards a unified conceptual framework. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 34(3): 318-335.

- Wolf HL, Morrish SC, Fountain J (2016) A conceptualization of the perceptions and motivators that drive luxury wine consumption. International Journal of Wine Business Research 28(2): 120-133.

- Amatulli C, Pino G, Angelis MD, Cascio R (2018) Understanding purchase determinants of luxury vintage products. Psychology & Marketing 35(8): 616-624.

- Xiao J, Li C, Peng L (2018) Cross-cultural effects of self-discrepancy on the consumption of counterfeit branded luxuries. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 30(4): 972-987.

- Atwal G, Bryson D, Tavilla V (2019) Posting photos of luxury cuisine online: an exploratory study. British Food Journal 121(2): 454-465.

- Kessous A, Valette-Florence P (2019) ‘“From Prada to Nada”: Consumers and their luxury products: A contrast between second-hand and first-hand luxury products. Journal of Business Research 102: 313-327.

- Peng N, Chen A (2019) Luxury hotels going green – the antecedents and consequences of consumer hesitation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27(9): 1374-1392.

- Hee-Jung LEE (2020) ‘The Anti-consumption Effect on the Car Sharing Utility: The Moderating Effect of Brand Luxury Level’, Journal of Distribution Science 18(6): 63-75.

- Pantano E, Stylos N (2020) The Cinderella moment: Exploring consumers’ motivations to engage with renting as collaborative luxury consumption mode. Psychology & Marketing 37(5): 740-753.

- Peng N (2020) Luxury restaurants’ risks when implementing new environmentally friendly programs – evidence from luxury restaurants in Taiwan. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32(7): 2409-2427.

- Wang O, Somogyi S (2020) Motives for luxury seafood consumption in first-tier cities in China. Food Quality and Preference 79: 103780.

- Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Lee TJ (2020) A culture-oriented model of consumers’ hedonic experiences in luxury hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 399-409.

- Guzzetti A, Crespi R, Belvedere V (2021) Please don’t buy!”: Consumers attitude to alternative luxury consumption. Strategic Change 30(1): 67-78.

- Olsen SO, Skallerud K, Heide M (2021) Consumers’ evaluation and intention to buy traditional seafood: The role of vintage, uniqueness, nostalgia and involvement in luxury. Appetite 157: 104994.

- Vincent RL, Gaur SS (2021) Luxury for Hire: Motivations to Use Closet Sharing. Australasian Marketing Journal 29(4): 306-319.

- Chen N, Petersen FE, Lowrey TM (2022) The effect of altruistic gift giving on self-indulgence in affordable luxury. Journal of Business Research 146: 84-94.

- Geerts A, Masset J (2022) Luxury tourism through private sales websites: Exploration of prestige-seeking consumers’ motivations and managers’ perceptions. Journal of Business Research 145: 377-386.

- Iyer R, Babin BJ, Eastman JK, Griffin M (2022) Drivers of attitudes toward luxury and counterfeit products: the moderating role of interpersonal influence. International Marketing Review 39(2): 242–268.

- Kim Y, Oh KW (2022) The effect of materialism and impression management purchase motivation on purchase intention for luxury athleisure products: the moderating effect of sustainability. Journal of Product & Brand Management 31(8): 1222-1234.

- Miller CJ, Brannon DC (2022) Pursuing premium: comparing pre-owned versus new durable markets. Journal of Product & Brand Management 31(1): 1-15.

- Ruan Y, Xu Y, Lee H (2022) Consumer Motivations for Luxury Fashion Rental: A Second-Order Factor Analysis Approach. Sustainability 14(12): 7475.

- Ndereyimana SC, Lau AKW, Lascu DN, Manrai AK (2022) Luxury goods and their counterfeits in Sub-Saharan Africa: a conceptual model of counterfeit luxury purchase intentions and empirical test. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 34(6): 1222-1244.

- Silva SC, Duarte P, Sandes FS, Almeida CA (2022) The hunt for treasures, bargains and individuality in pre-loved luxury. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 50(11): 1321-1336.

- ul Hasan HMR, Lang C, Xia S (2022) Investigating Consumer Values of Secondhand Fashion Consumption in the Mass Market vs. Luxury Market: A Text-Mining Approach. Sustainability 15(1): 254.

- Zainurin F, Neill L, Schänzel H (2022) Considerations of luxury wine tourism experiences in the new world: three Waiheke Island vintners. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 21(3): 344-353.

- Liu F, Li J, Mizerski D, Soh H (2012) Self‐congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: a study on luxury brands. European Journal of Marketing. 46(7/8): 922-937.

- Gibson P, Seibold S (2014) Understanding and influencing eco-luxury consumers. International Journal of Social Economics 41(9): 780-800.

- Ahn S (2015) THE EFFECT OF LUXURY PRODUCT PRICING ON CONSUMERS’ PERCEPTIONS ABOUT CSR ACTIVITIES, Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 19(3): 1-14.

- Hassan S, Husić-Mehmedović M, Duverger P (2015) Retaining the allure of luxury brands during an economic downturn: Can brand globalness influence consumer perception?’ Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 19(4): 416-429.

- Roy R, Rabbanee FK (2015) Antecedents and consequences of self-congruity. European Journal of Marketing 49(3/4): 444-466.

- Alexander B, Contreras LO (2016) Inter-industry creative collaborations incorporating luxury fashion brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 20(3): 254-275.

- Taube J, Warnaby G (2017) How brand interaction in pop-up shops influences consumers’ perceptions of luxury fashion retailers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 21(3): 385-399.

- Pentina I, Guilloux V, Micu AC (2018) Exploring Social Media Engagement Behaviors in the Context of Luxury Brands. Journal of Advertising 47(1): 55-69.

- Zainol Z, Phau I, Cheah I (2018) Development and Validation of Consumers’ Need for Ingredient Authenticity (CNIA Scale). Journal of Promotion Management 24(3): 376-397.

- Li J, Guo S, Zhang JZ, Sun L (2020) When others show off my brand: self-brand association and conspicuous consumption. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 32(6): 1214-1225.

- Martín-Consuegra D, Díaz E, Gómez M, Molina A (2019) Examining consumer luxury brand-related behavior intentions in a social media context: The moderating role of hedonic and utilitarian motivations. Physiology & Behavior 200: 104-110.

- Klaus P ‘Phil’ (2020) The end of the world as we know it? The influence of online channels on the luxury customer experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 57: 102248.

- Mrad M, Majdalani J, Cui CC, Khansa ZE (2020) Brand addiction in the contexts of luxury and fast-fashion brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 55: 102089.

- Jansom A, Pongsakornrungsilp S (2021) How Instagram Influencers Affect the Value Perception of Thai Millennial Followers and Purchasing Intention of Luxury Fashion for Sustainable Marketing. Sustainability 13(15): 8572.

- Kapferer JN, Valette-Florence P (2021) Which consumers believe luxury must be expensive and why? A cross-cultural comparison of motivations. Journal of Business Research 132: 301-313.

- Kim S, Park K, Shrum LJ (2022) Addressing the Cause-Related Marketing Paradox for Luxury Brands to Increase Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being. Journal of Macromarketing 42(4): 624-629.

- Phau I, Akintimehin OO, Shen B, Cheah I (2022) “Buy, wear, return, repeat”: Investigating Chinese consumers’ attitude and intentions to engage in wardrobing. Strategic Change 31(3): 345-356.

- Singh J, Shukla P, Schlegelmilch BB (2022) Desire, need, and obligation: Examining commitment to luxury brands in emerging markets. International Business Review 31(3): 101947.

- Zhang J, Chen M, Xie Z, Zhuang J (2022) Don’t fall into exquisite poverty: The impact of mismatch between consumers and luxury brands on happiness. Journal of Business Research 151: 298-309.

- Jain S, Mishra S, Saxena G (2023) Luxury customer’s motivations to adopt gamification. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 41(2): 156-170.

- Ma J, Zhao Y, Mo Z (2023) Dynamic Luxury Advertising: Using Lifestyle versus Functional Advertisements in Different Purchase Stages. Journal of Advertising 52(1): 39-56.

- Hemetsberger A, von Wallpach S, Bauer M (2012)'Because I'm Worth It': Luxury and the Construction of Consumers' Selves'. Advances in Consumer Research 40: 483-489.

-

Shin’ya NAGASAWA* and Yingyu Li. Systematic Literature Review on Consumer Motivations Regarding Luxury. J Textile Sci Page 8 of 11 & Fashion Tech 10(3): 2023. JTSFT.MS.ID.000736.

-

Luxury, Luxury Consumption, Consumer Motivation, Consumer Behavior, Systematic Literature Review

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.