Research Article

Research Article

The German Adjective: The History of Its Declensions and Their Usage from the Beginning to the Present

Jens Erik Mogensen, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Received Date: April 11, 2025; Published Date: April 22, 2025

Summary

This paper addresses the declension of adjectives in German over a period of approximately 1,275 years: from ancient German to the present. After a terminological discussion, the paper provides an overview of the morphology of adjectival inflections from a synchronic as well as a diachronic perspective. It is shown how phonological change affects the morphological paradigms towards an increasing degree of homonymy, in particular in the weak declension. I argue that the so-called Ø-forms are a key deviation from modern German. They peak in Early New High German and are particularly interesting because they could have led to simpler paradigms, but do not. They disappear from the nominal group, and are today retained only in the verbal syntax. After a systematic review of the syntactic functions and their inflectional relationships, a discussion of the use of the declension types follows. Linguistic change here navigates the tension between a functionalist-semantic and a syntactic-mechanical principle, between ‘monoflexion’ and ‘polyflexion’, between variance and linguistic normalization. The article includes questions for future research.

Keywords: Historical linguistics; Morphology; Syntax; Semantics; Adjectives; Linguistic change

Introduction

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the adjective declensions and their usage throughout the history of the German language – i.e., from circa 750 CE to the present. The article is written for educators, researchers, university students, and any other reader who needs a brief but coherent and historically based understanding of the subject. The article is not only aimed at German philologists but also, for example, general linguists, Indo-Europeanists, historians, and theologians. There already exist different approaches to the subject, such as synchronic grammars of each period of the German language [1] or diachronic introductions and workbooks, often focusing on a single linguistic aspect (e.g. historical syntax) or one specific period [2]. However, the existing presentations are, in general, terminologically diverse, written over a long period of time, and range in detail and difficulty from very brief presentations to comprehensive scientific monographs. There seems to be a lack of brief, terminologically uniform presentations that enable easy comparisons along the different periods of the German language from its beginnings to the present. The present article attempts to fill this gap. It also identifies and proposes areas for further research. The morphology of the declensions and their syntax, from the beginning to the present, are discussed below. The article concentrates on High German – i.e., the German varieties that lead to the standard German language.

Morphology

This chapter addresses the morphology of the adjective declensions. After a terminological discussion, the grammatical categories of the word class are described. The morphology of the adjective declensions in the different periods of the language is then discussed.

Terminology

‘Strong’ and ‘weak’ declension

All German adjectives – with terms that originate from Jacob Grimm – can be inflected according to two declensions: strong and weak [3]. The strong declension is the oldest and is known from all Indo-European languages. The weak declension is an innovation in the Germanic languages [4]. In Indo-European, the strong declension was identical to the declension of vowel noun stems. In historical linguistics, it is therefore also called the vocalic declension; the weak declension is called consonantal or simply the n-stem declension, as the weak declension is basically identical to the declension of weak nouns (i.e., the declension of the n-stems) [5]. The strong adjective declension is a different story. As mentioned, the starting point for the strong adjective declension is also the declension of nouns, namely that of vowel stems. In Proto-Indo- European language, there seems to have been no morphological distinction between nouns and adjectives [6]. However, already in Proto-Germanic, the strong adjective declension begins to orientate itself more towards the demonstrative pronoun [7]. As a result, the strong adjective declension consists of a mixture of nominal and pronominal endings right up until nineteenth-century German [8]. In the Germanic languages, the nominal endings – presumably due to the Germanic initial accent – are weakened to -Ø, unlike Latin, for example: bonus (masculine), bona (feminine), bonum (neuter). Already in Old High German, the strong nominal adjective ending is -Ø, for example guot-Ø (guot man, guot frouwa, guot kind) [9]. This will be discussed further below. How the strong and weak inflections are used in the different periods of German will be discussed in the main section on syntax.

The metaphors ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ reflect Romanticism, i.e. the movement of intellectual history that characterized the time in which Jacob Grimm lived. Romanticism, and thus Grimm, equates the ‘old’ with the ‘strong’. This means that the oldest grammatical forms are primary and thus the stronger ones. The younger forms are secondary and therefore, according to Grimm’s logic, ‘weak’ [10]. Partly, the metaphor may also indicate how the weak declension cannot express as many case distinctions as the strong [11]. Since Grimm, most linguists and grammarians have used the terminology ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ in relation to adjectives, nouns, and verbs. However, some linguists have tried to propose an alternative terminology. For example, the Polish linguist Józef Darski introduces the terms ‘determining’ versus ‘non-determining’ declension, emphasizing that the declension of adjectives should be seen as a group reflection, i.e. dependent on the nominal group as such [12]. Bergmann/Pauly use the terms ‘pronominal’ versus ‘nominal’ inflection [13]. However, as we have already seen, the strong inflection does not only consist of pronominal but also nominal endings, which is why this terminology has been criticized [14]. The distinction only makes sense if a tripartite division between pronominal/ strong, nominal/strong, and nominal/weak were introduced, but this seems to complicate the picture unnecessarily.

In addition to the strong and weak declension, some modern school grammars – and, for example, the British philologist William B. Lockwood – introduce a third adjective declension, namely a socalled ‘mixed’ declension, which is assumed to be used after the indefinite article and other determiners that inflect like the indefinite article [15]. However, this is neither a diachronically justified declension, nor is it meaningful from a synchronic point of view, as it makes the description of the system regulating declension unnecessarily complicated [16]. The so-called mixed declension is therefore not used in this article.

In this article, like most linguists, I use the terms strong and weak. Grammatical terms are technical terms and only have a defined content. Jakob Grimm’s original motivation for choosing these terms is, in my view, irrelevant in this respect. The terms are well-defined in linguistics and enable coherent comparisons between different grammatical texts spanning more than 200 years.

Ø, inflected and uninflected, pronominal and nominal

It is a basic principle in linguistics that the morpheme Ø is included in the inflectional paradigms when the absence of an ending stands in opposition to a manifest ending – i.e., an ending with a material expression side (the opposition principle) [17]. Thus, in Old High German, guot man (nominative singular) is in paradigmatic opposition to, for example, guotan man (accusative singular) and can be segmented as guot-Ø man versus guot-an man. Additionally, -Ø and -êr, when they appear as a possibility in the same place in the paradigm, can be labelled as facultative allomorphs of one morpheme (nominative singular masculine guot-Ø man vs. guotêr man). The morpheme Ø is often used in the present article. For example, as will be shown below, in the strong inflection of adjectives, there may be an original nominal form (e.g. guot-Ø man) versus a pronominal form (guot-êr man). This kind of segmentation is a structuralist approach that is not always reflected in historical grammars, as these often have their roots before structuralism. In general, the terminology ‘uninflected’ versus ‘inflected’ are typically used – often with the addition of the adjective “so-called” (the so-called uninflected forms) – or the word “uninflected” is placed in quotation marks. For example, the following is stated in two German textbooks (translated from German into English by me):

• The ‘uninflected’ form is only apparently uninflected; it is the old form of the strong nouns [18].

• The so-called uninflected forms have arisen through the loss of endings because of the Germanic auslaut laws [19].

The Ø-morpheme can have different diachronic origins. Thus, in Early New High German, where Ø occurs frequently in the paradigms, Ø can originate from nominal forms as in Old High German but can also be the result of the loss of an -e in the final position of the word (apocope), analogy, or ecthlipsis (see below). If paradigms can be established where Ø is used in opposition to a manifest allomorph, it makes sense to use the Ø-morpheme. However, during language history, cases arise where the original opposition between Ø and a manifest morpheme is no longer clear. This applies, for example, to adjectives with the syntactic function predicative in modern German: der Mann ist blind; die Männer sind blind. From a diachronic perspective, blind is a nominal Ø-form. The allomorphic opposition between Ø and a manifest morpheme is still clear in Old High German: der man ist blint-Ø versus der man ist blint-êr; die man sint blint-Ø versus die man sint blint-e [20]. But in modern German, a synchronic paradigm cannot be set up where Ø stands in opposition to a manifest morpheme in the predicative function. And it would be extremely abstract to create a paradigm that considers all diachronic varieties. Thus, it makes the most sense to use the term ‘uninflected’ when no paradigms can be established between Ø and a manifest morpheme. In other words, I sometimes use the term ‘uninflected’ below, knowing that this is historically the Ø-morpheme, which in certain periods has stood in opposition to a manifest morpheme.

Grammatical categories

The adjective is a word class which, like other inflectional word classes, has a certain number of grammatical categories. These grammatical categories, in turn, have a fixed set of values, sometimes called grammemes. The number of items in the grammatical category depends on the number of formal differences in the system [21]. The number of grammatical categories and the corresponding grammemes diverge from language to language. A cursory comparison of adjective inflectional endings in different Germanic languages shows that German is a much more formal language than, for example, English and Danish. Whereas in English the adjective is uninflected, Danish has three possible inflections, while modern German has six. This can be illustrated by the adjective red, in Danish rød and in German rot:

• English: red

• Danish: rød-Ø, rød-e, rød-t

• German: rot-Ø, rot-e, rot-er, rot-en, rot-em, rot-es

In German, the adjective has both more grammatical categories and more values in its grammatical categories than other Germanic languages such as English or Danish. The German adjective has the following grammatical categories:

• Case

• Number

• Gender

• Declension type

• Comparison

This article addresses the declensions of adjectives, so comparison will not be discussed here.

The grammatical categories each contain a set of values. Thus, the category case has four values in modern German: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative. In Old High German, there is also a remnant of a fifth value, instrumental. The category gender has three values: masculine, feminine, neuter. The category number has two categories: singular, plural. The category declension type has two values: strong, weak.

Old High German (750-1050)

Old High German represents the oldest German, with texts dating from around 750 to 1050. The period has a predominance of religious texts, especially Bible translations, which were used in the Christian mission. Linguistically, the period is characterized, among other things, by the fact that there are only dialects, meaning that no standard norm has yet been developed. This means that, from a system perspective, the degree of linguistic variation is high. In general, the period is also characterized by the fact that full vowels, long and short, are found both in the stressed and unstressed syllables of words. After the Old High German period, all vowels in unstressed syllables generally weaken to the schwa vowel [ə]. The existence of full vowels in the unstressed syllable allows for a highly developed inflectional system in which the individual vowels carry the grammatical content. This becomes more difficult after the weakening to schwa, which is why the grammatical content is later increasingly carried by auxiliary words such as articles and auxiliary verbs.

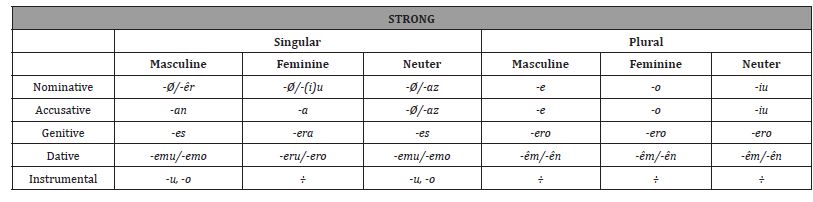

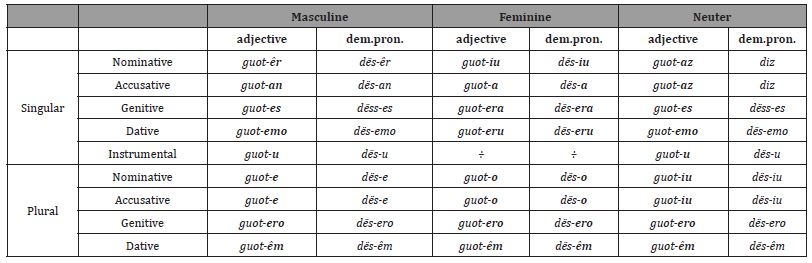

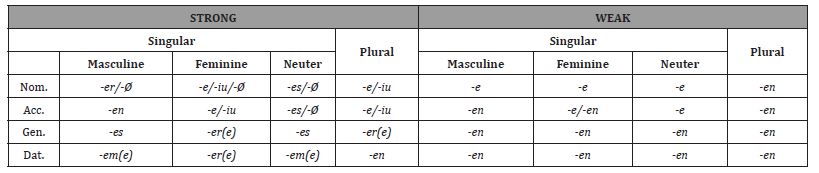

The Old High German adjective has a total of at least 25 different declension allomorphs: -Ø, -êr, -an, -es, -emu, -emo, -u, -o, -iu, -a, -era, -eru, -az, -e, -ero, -êm, -ên, -on, -un, -en, -ûn, -on, -ôno, -ôm, -ôn. The homonymy rate is thus much lower than in other periods of the linguistic history of German. The adjective morphemes in Old High German can be listed in the following two tables, one for the strong and one for the weak declension:

Table 1:

Table 2:

Adjectives such as blint, alt, guot, siuh, snël, stum, and heilag can be inserted into the tables [22].

The table of the strong declension is based on most adjectives which, in their basic form, end in a consonant – i.e., the so-called a-stems (masculine and neuter) and ô-stems (feminine). In addition, there are so-called ja- and jô-stems and wa-/wô-stems. The adjectives which are ja-/jô-stems end in the nominal form with -i (mâri). The present participles belong to this group (e.g. nëmanti). The wa-/wô-stems end, in their basic form, in -o (e.g. garo). The latter type is not very frequent. Apart from that, these stems do not differ from the endings in the table; synchronously, the stem class affiliation cannot be recognized apart from the basic form. Mari and garo could even be analysed as mari-Ø and garo-Ø, which would mean that there is synchronically no difference between the stems in terms of the endings.

Here a few examples from Old High German original texts [23]:

a. Strong declension:

Ubel man (N); salig tod (N); ein michel geuualt (N); pe einemo smalemo fademe (N); in einero churzero uuilo; sinan einegan sun (O); ein armaz wib (Hildebrandslied); sô friuntlaos man (H); gisah man blintan fon giburte (T); sidh uuarth her guot man (‘later he became a good man’) (L); themo unûbremo geiste (T); thaz scônaz annuzzi (O); ir almahtic got (‘He, the almighty God’); fona alten ioh fone niuuen ziten (N)

b. Weak declension:

Ther guato man; min arbeitsamo lîb (N); uf einemo blanchen ross (N); then liobon drost; min liobo sun (T); liobo man (O); fon himilsgen liothe (O) (‘from the heavenly light’).

At first glance, the inflectional endings appear to be very different from those known from modern German. In fact, only two endings appear to be the same in modern German, namely -e [24] and -en [25]. However, with a little insight into phonological change, it quickly becomes clear that most of the endings are the same as in modern German. The endings have simply undergone the regular sound changes. For example, when -a, -o, -an, -on, -un, -az and -ero are weakened to schwa (see above) and the final vowels undergo apocope, the result is the familiar inflections -e, -en, -es, and -er.

However, there are, at the systemic level, four major differences compared to later periods:

1. There are three genders, not only in the singular but also in the plural: masculine, feminine, and neuter. In modern German, the gender opposition is neutralized in the plural. However, as seen in the tables, there are already examples of gender syncretism in the plural paradigm (genitive and dative, both strong and weak declension).

2. A lower degree of syncretism (homonymy) compared to the following periods of the language. Despite a certain degree of syncretism, there are far more distinct endings. On the other hand, there are examples of syncretism also in the Old High German declensions. For example, the case opposition between genitive and dative is neutralized in singular as well as nominative and accusative plural, weak declension. In fact, only the ending -an is not homonymous; it occurs only once in the paradigms (accusative singular masculine, strong declension).

3. There is a case instrumental with independent endings in the strong declension, singular masculine, and neuter. The case instrumental disappears after the Old High German period.

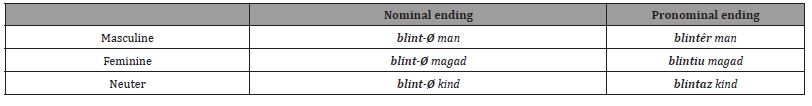

4. In the singular masculine and feminine, there are two possibilities in the nominative case and in the neuter case also in the accusative: either -Ø or a manifest ending -êr, -(i)u, -az.

The suffix -Ø is a nominal suffix that is parallel to the strong nouns, for example tag-Ø, geba-Ø, and uuort-Ø. The manifest endings -êr, -(i)u, and -az are pronominal. The nominal and pronominal endings are used without semantic difference [26]:

Table 3:

The nominal endings, which are considered older than their pronominal counterparts [27], are still common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, especially in the neuter.

The pronominal endings of the strong declension are parallel to the endings of the compound demonstrative pronoun. This can be illustrated in the following table:

Table 4:

The weak adjective inflection endings are oriented towards the weak nouns, for example hano, zunga, and hërza. A vocalic ending is only found in the nominative and accusative singular, masculine, and neuter. Otherwise, the suffix ends in -n (cf. also the popular term ‘n-inflection’).

Middle High German (1050-1350)

Middle High German represents German from around 1050 to 1350. Like Old High German, Middle High German is generally characterized by the existence of numerous dialects next to each other with no overall standard linguistic norm; in other words, there is, at all linguistic levels, still a high degree of linguistic variation. At the same time, though, there is a tendency towards a supra-regional literary language of art, namely the so-called Classical Middle High German, a linguistic variety developed and used by the knighthood. It disappears again in the fourteenth century with the decline of chivalry. Middle High German is characterized by more text genres than Old High German, including poetry and epic, as represented by, for instance, Hartmann von Aue, Gottfried von Straßburg, Walther von der Vogelweide, and Wolfram von Eschenbach, as well as religious literature by religious mystics such as Hildegard von Bingen, Mechthild von Magdeburg, and Meister Eckhart. The text editions often have a greater linguistic unity than the original manuscripts, which is partly due to the editorial philological practice of the nineteenth century, not least the philologist Karl Lachmann’s Middle High German orthography, often referred to as “normalized” Middle High German.

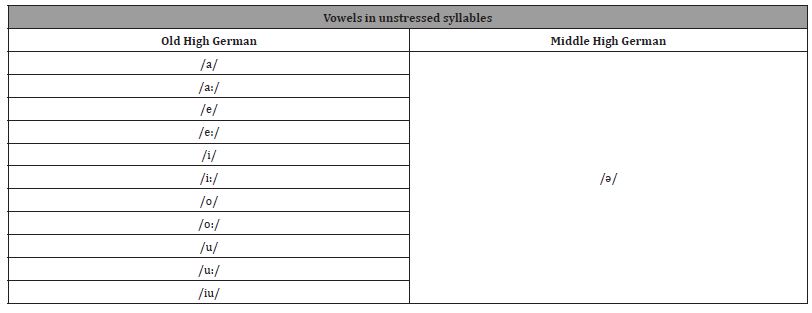

The main linguistic difference between Old High German and Middle High German is that after the Old High German period, all vowels in unstressed syllables generally weaken to the schwa vowel [ə].

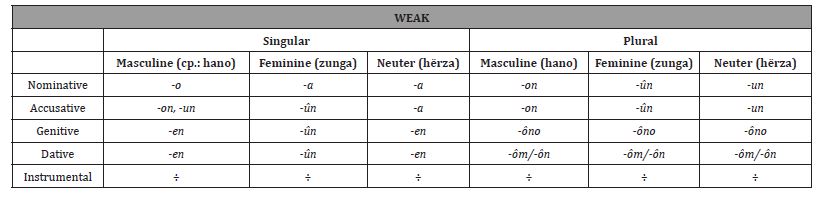

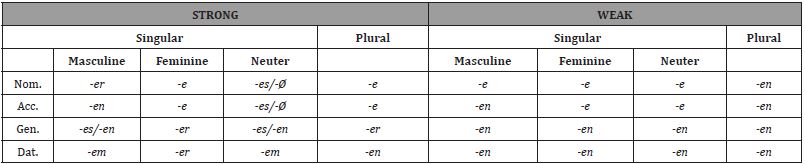

Table 5:

As a result of this phonological change, the inflectional system no longer has the same set of individual vowels, which before the Middle High German period could carry much of the grammatical content. After the weakening to schwa, the grammatical content is increasingly carried by auxiliary verbs, and the evolution from synthetic to analytical language is accelerating. Whereas Old High German had at least 25 different declension allomorphs, Middle High German has nine: -Ø, -e, -en, -er, -es, -em(e), -iu, -er(e), and -ez. As a result of extensive syncretism, the degree of homonymy has increased: -en in Middle High German, for example, represents 14 morphemes {-en1, -en2, [….] -en14} compared to four in Old High German {-en1, -en2, -en3, -en4}. The Middle High German ending -en of the strong declension now coincides with the ending -en in the weak declension in the plural of all cases, and in the accusative, genitive, and dative singular masculine and feminine, as well as the genitive and dative, neuter. Thus, the highly homonymous Middle High German adjective ending -en corresponds to the Old High German adjective endings -an, -on, -ûn, -ôm, -ôno, -un, and -ûn.

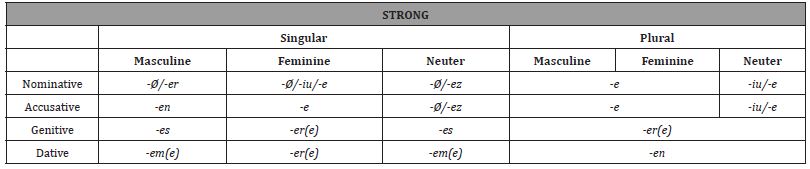

The adjective endings in Middle High German can be listed in the following two tables, one for the strong and one for the weak declension.

Table 6:

Table 7:

Like Old High German, the table of the strong declension is based on the so-called a-stems (masculine and neuter) and ô-stems (feminine). Most adjectives are inflected this way, for example alt, diutisch, geloubec, gewaltic, guot, hôch, irdisch, lang, liep, rëht, stum, and tôt [28]. As in Old High German, there are also ja-/jô-stems and wa-/wô-stems. The adjectives which are ja-/jô-stems and in Old High German in the nominal form end in -i (mâri), and in Middle High German – because of the weakening of the i to schwa – end in -e, for example lære (NHG ‘leer’), lobebære, enge (NHG ‘eng’), strenge (NHG ‘streng’), müde, küene, ziere. The Old High German -i, as an umlaut factor, has induced umlauts in the stems whose vowels can have umlauts [29]. The wa-/wô-stems in Middle High German end in -a in the base form (e.g., bla ‘blue’), but keep the original w in the inflected forms (e.g., blawer ‘blue’). Adjectives and participles ending their stem in -en often lack the -en morpheme (e.g., mit ûfgebunden helmen) [30].

In comparison with Old High German, linguistic change in Middle High German has – apart from the vowel weakening or, rather, because of it – taken place in the following areas:

1. In the plural, the gender opposition is (largely) neutralized. However, the suffix -iu in nominative and accusative plural neuter differs from the suffix -e in the plural masculine and feminine, so in this instance there is still gender opposition, at least in the Upper German dialects. In the Middle German dialects, the gender opposition is completely neutralized: The ending in the nominative and accusative plural neuter is, in these dialects, also -e. This is because -iu had already become -u in Old Franconian, and this -u weakens to -e (schwa) in Middle High German.

2. The case opposition is largely neutralized in the weak declension (totally in the plural, partially in the singular).

3. Extensive homonymisation of the inventory and collapse of morphological opposition due to syncretism is because of the vowel weakening from full vowels to schwa in unstressed syllables.

4. The case instrumental, of which there are remnants in Old High German, has now been eliminated from the system, as there are no longer any specific morphemes.

A brief comparison with modern German shows that:

5. The weak adjective inflection is (almost) the same in Middle High German and Modern German, apart from the ending -en in the accusative singular feminine; -e in Modern German. This means that, for example, [ich sach] die guoten vrouwen can be both accusative singular and plural and thus correspond to modern German die gute Frau as well as die guten Frauen [31].

6. The strong inflection, unlike modern German, but like Old High German, has both a nominal form -Ø as well as a manifest, pronominal ending in the nominative singular masculine and feminine, and in the neuter also in the accusative.

7. Genitive singular masculine has the ending -es as opposed to modern German -en.

8. The endings -er and -em have the variants -ere and -eme. These variants are mainly found in the transition between Old High German and Middle High German, especially later in Middle German [32].

9. Nominative singular feminine has the ending -iu as opposed to modern German -e. However, -e does occur in Middle German.

Early New High German (1350-1650)

Early High German represents German from around 1350 to 1650. Compared to the previous two periods, cities have grown in importance, more people can read and write, paper replaces the much more expensive parchment at the end of the fourteenth century, Gutenberg invents printing in the mid-fifteenth century, and there are many more text types than before. The language is characterized by a considerable diversity of variants, even within the same text [33]. Written consonant clusters are typical, as from the fifteenth century when writers were paid by the line, which, of course, incentivized long words [34]. Martin Luther’s innovative approach to language, both as a translator and creator of new words and spellings, is significant and leaves its mark on what would later become a linguistic standard. However, there is still not one recognized standard variety but several different varieties such as dialects, printed languages, sociolects, and technical languages [35].

The main linguistic difference between Middle High German and Early New High German are:

• The diphthongization of the monophthongs î, iu [y:], and û > ei, eu, au (e.g. mîn niuwes hûs > mein neues haus)

• The Middle German monophthongization ie, uo, üe > î, û, [y:] (liebe guote schüeler now monophthongized in the Middle German dialects)

• Numerus profiling of the feminine nouns [36]

• Short vowels become long in open syllable (Middle High German faren, nemen, vogel > Early New High German fah/ren, neh/ men, vo/gel) [37]

• Certain equalisations in the person endings of verbs [38] However, these five characteristic linguistic developments do not affect the declension of adjectives.

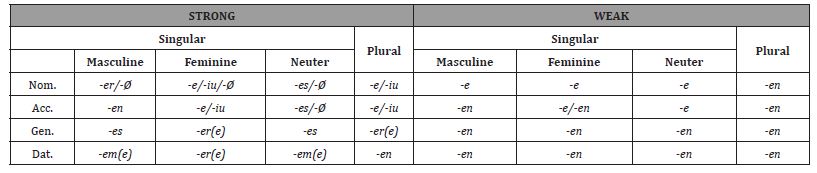

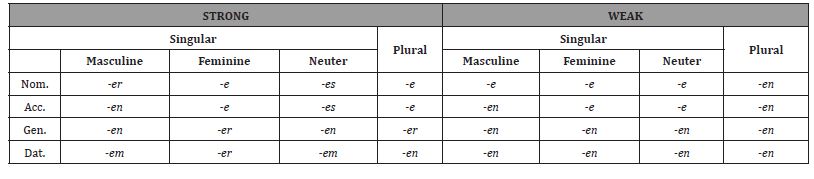

The adjective endings in Early New High German are listed here:

Table 8:

Since Early New High German is characterized by many possible facultative variants, also regarding the declension of adjectives and their diasystematic anchoring, the schematic overview cannot be exhaustive but only shows the main tendencies. The variants can be studied in their diasystematic breadth in a scientific grammar of the period [39]. Here are just a few comments.

Whereas Old High German had at least 25 different declension allomorphs, Middle High German and Early New High German has nine [40].

In the table, the suffix -Ø is only included when -Ø can be assumed to correspond to the original nominal forms (see above). But, in fact, -Ø in Early New High German occurs at a systematic level everywhere in the declension paradigms of the Early New High German adjective [41]. It is, however, generally difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether the -Ø is the original nominal declension, analogy, e-apocope, or ecthlipsis [42]. The uninflected forms persist, over time, especially in the neuter. Some examples of uninflected attributive adjectives in Early New High German [43]:

Ein pitter tod, der allmechtig Gott, die alt buß, eine edel fraw, ein verschlossen garten, der weiß man, lang zytt, kein griechisch wort, in gros trurikeit, ein gegossen Kalb (‘a molten calf’), neüw rathsbuch, ein gut werck, ein christlich herz, groß krieg und hadder, di swanger frauwen, and Martin Luther: Groß Macht und viel List | sein grausam Rüstung ist.

The main difference between the adjective declensions in Early New High German and New High German/Modern German is the frequent use of the ending -Ø (‘uninflected’ form) in Early New High German [44].

Some grammars state that, in the weak declension, nominative, and accusative plural, the suffix -e occurs next to -en [45]. Another and more common interpretation are that the ending -e belongs to the strong inflection and that the boundaries between strong and weak were not as firm as they were later [46]. This seems difficult to determine.

In comparison with Middle High German, the suffix in the accusative singular feminine was in Middle High German -en (thus, die guoten vrouwen could be both singular and plural). In Early New High German, a disambiguation seems to be taking place, as the suffix -e is now occurring as a possibility in the singular, whereas the plural suffix stays -en. The suffix -en, in the accusative singular feminine, occurs into the fifteenth century. Luther uses -en until 1540 (e.g., die heiligen schrift, uber die gantzen Erde) [47].

A comparison with modern German shows, apart from the frequent use of the Ø suffix as described above, the following differences:

Strong declension:

• In the nominative and accusative singular feminine, -iu is found next to -e

• In the genitive and dative singular feminine, -ere is found next to -er

• In the dative singular masculine and neuter, -eme is found next to -em

• In the genitive singular masculine and neuter, the ending is -es (modern German: -en)

• In the nominative and accusative plural, -iu is found next to -e

• In the genitive plural, -ere is found next to -er Weak declension:

• In the accusative singular feminine, -en is found next to -e (see above).

New High German and Modern Standard German (1650 - present)

From the seventeenth century onwards, German is characterized by greater uniformity than in previous periods and by attempts to standardize the language through systematization and rules (e.g. Schottel, Opitz, Gottsched and Adelung). Language societies emerged and grammars and dictionaries were published. However, there was still no single cultural and political centre and basically no single national literature. From the second half of the eighteenth century, however, a literary language emerged that gained prestige and distinguished itself from the dialects. Only after the unification of the German Empire in 1871, however, did a standard variety develop as we know it today.

Table 9 shows the morphology of adjective declensions in New High German.

Table 9:

The morphology shown in Table 9, which is familiar from modern German, is fixed from around the seventeenth century. There are only two deviations from modern German:

1. The suffix in the genitive singular masculine and neuter is -es (e.g. reines Herzens) at the beginning of the period, but is increasingly replaced by -en as it is known from modern German (reinen Herzens). It is difficult to determine whether the -en is borrowed from the weak inflection due to the principle of monoflexion or is a special sound development [48]. Some linguists argue that the development is probably ‘done for euphony, to avoid the two hissing -s-endings’ [49].

2. The nominal form -Ø still exists, competing with the pronominal form -es, in the nominative and accusative neuter singular up into the nineteenth century, for example ein jung und artig Weib (Lessing), ein unnutz Leben (Goethe), ein liebend Paar (Schiller), cf. also the proverb ein gut Gewissen | ist ein sanftes Ruhekissen. After that, it is completely replaced by the pronominal form and can now only be found in a few idioms, like auf gut Glück.

The following overview shows the interaction of adjective grammatical categories and values in Modern Standard German.

Table 10:

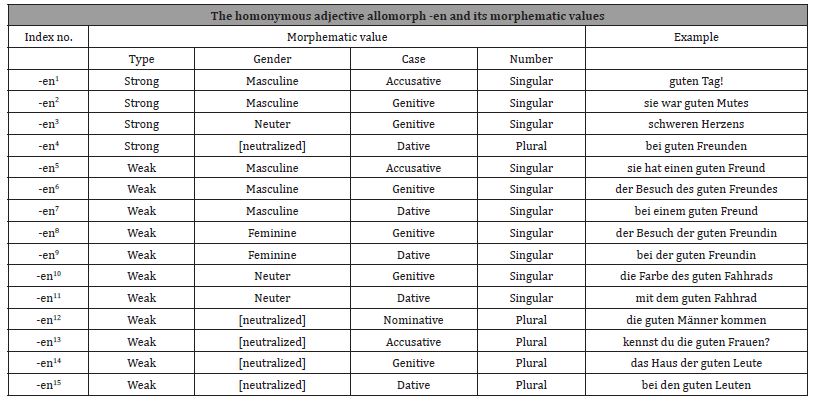

Allomorphs and morphemes

The adjective has six possible declension allomorphs in Modern German: -Ø, -e, -er, -en, -em, -es. It could be argued that a set of four more allomorphs should be added: -r, -n, -m, -s. This would apply to situations where the adjective stem ends in -e, and the -eof the adjective ending seems to be left out (e.g., leise: leise-Ø, leise-r, leise-n, leise-m, leise-s). This would mean that the allomorphs in, for instance, nominative and accusative singular feminine as well as nominative and accusative plural would be -Ø (eine leise-Ø Stimme; leise-Ø Stimmen), and that the endings at the morphemic level should be noted as either -e/-Ø or -(e). On the other hand, it could be argued that it is not obvious why the e-loss is merely a matter of the ending; it might even be seen a loss of the -e of the stem (leis-e, leis-er, leis-en, leis-em, leis-es). In fact, it is, from a synchronic perspective, hardly possible to decide whether the e-loss takes place in the lexical or grammatical morpheme. In fact, it is more of a phonological “collaboration” between stem and ending. The rule could be summarized as follows: e + e = e. I would therefore suggest treating the phenomenon as a phonological specialty, which should be mentioned only as an exception.

To conclude: The adjective in Modern German has six declension allomorphs, noting the phonological specialty that e + e = e. These allomorphs are, however, largely homonymous on the expression side, as they can express different grammatical contents. For example, the inflectional ending -en, which is the most homonymous inflectional allomorph of the German adjective declension, expresses, due to extensive syncretism, fifteen different inflectional morphemes {-en1, -en2, …. -en15}:

Table 11:

As you can see, the endings in the strong declension are less homonymous than in the weak declension.

Syntax

This chapter first addresses the question of the declension of the adjective in its various syntactic functions. It then discusses the use of the weak and strong declension throughout the history of the German language.

Syntactic functions

The adjective has the following syntactic functions: attributive, predicative, substantive, and adverbial [50].

1. The adjective has the function attributive if it is subordinate to a noun (N) in a noun phrase (NP)

2. The adjective has the function substantive if it used as the N in a NP

3. The adjective has the function predicative if it represents a NP which refers semantically to either the subject or the object, and is not itself the subject or object

4. The adjective has the function adverbial if it is either adverbial or adverbial attribute of an adjective.

These four syntactic functions of the adjective stay the same in all periods of the German language. However, the periods differ when it comes to the question of whether the adjectives in these syntactic functions are ‘uninflected’ (Ø-ending, nominal ending, uninflected) or inflected with a manifest ending. It should be noted that I use the term uninflected here based on the definition and for the reasons I explained in the terminology section above. Inflected here means inflected with a manifest ending.

In general, the adjective can be inflected in all four functions in Old High German, while in modern German it is only inflected in functions 1 and 2. Below, the syntactic functions are reviewed from a diachronic perspective.

Attributive function

When used in its attributive function, the adjective can topologically be both prepositive and postpositive. In all periods from Old High German to Modern German, the main rule is prepositive – i.e., as part of a nominal phrase, the adjective is placed to the right of the determiner and to the left of the noun. Examples from modern German include:

Table 12:

Already in Old High German, the attributive adjective is primarily prepositive: fona dhemu almahtigin fater (I), dher aerloso man (I), thes hohisten gotes (T), in thiu uzarun finstarnessi (T), then liobon drost (O), zemo hohen himilriche (O). Schrodt states that there are no postpositive examples from Tatian, and that there are only two from Isidor: gotes stimna hluda and after moysise dodemu. According to Schrodt, the examples from Otfrid’s Gospel Book are stylistically conditioned: buah frono, kinde zeizemo, sines libes unentliches, ze handen guoten. Only in Hildebrandslied is the postpositive position more frequent: degano dechisto, at burc enigiru, barn unwahsan [51]. Notker writes, for example, in einemo felde scônemo [52]. The nominal and pronominal strong endings are used in both cases without semantic difference: guot/guotêr man, man guot/guotêr [53]. The same is true in Middle High German. However, the nominal (uninflected) forms are mainly used in Upper German [54]. In New High German, the nominal forms disappear in the masculine and feminine, but they are still used in the neuter until the nineteenth century. The postpositive position is, in Middle High German, restricted for special stylistic purposes (der künec guot), for example the rhyme. Only in extremely rare cases is the attributive adjective postpositive in New High German. If so, it is uninflected (e.g., Röslein rot; ein Whisky pur) [55].

Substantive function

An adjective in the function as a noun is inflected (e.g., ein Jugendlich- er; der Jugendlich-e; Old High German: thio uuîs-ûn; ein tumb-iu [‘a fool’]; ein stumm-e) according to the rules of the attributive adjective. The adjective in this function is subject to the same restrictions as adjectives in the attributive function (you can interpolate a missing noun). When the word class ‘adjective’ is retained in this function, they are also called partially substantivized adjectives. Totally substantivized adjectives are something else, since a word class change from adjective to noun has taken place (e.g., Middle High German gesunt [health] or zart [tenderness, lover]). Such nouns are not discussed here.

Predicative function

The adjective is always uninflected in New High German when used predicatively, both in singular and plural (der Mann ist alt; die Männer sind alt). When the adjective is used for classification purposes, it sometimes seems to be inflected (e.g. diese Kirschen sind saure, in contrast to diese Kirschen sind süße). In this case, however, it could be argued that the adjective is in fact attributive as part of an elliptic construction: diese Kirschen sind saure [Kirschen] [56].

Diachronically, the uninflected form is the nominal form of the strong adjective declension (see above). In Old High German, the nominal (uninflected) form is the most frequent, but pronominal (inflected) adjectives are not rare either. There is no semantic difference between the nominal and the pronominal form.

Examples of nominal forms in Old High German:

• chûd was her […] chônnêm mannum ‘he was known [...] to bold men’

• kind uuarth her faterlôs (L) ‘as a child he became fatherless’

• thie zîti sint so heilag (O)

Examples of pronominal forms:

• du bist dir, altêr Hûn, unmet spâhêr (‘you are, old Hun, infinitely cunning’)

• er ist […] wîsêr inti kuani (O) (‘he is wise and bold’)

• ther blinder ward giboranêr (‘who was born blind’)

• thêr lîchamo ist iu fuler (O)

• fimui von dên uuarun dumbo inti fimui uuîso (T)

In Middle High German, adjectives in predicative function are generally nominal (uninflected) – ouch was sîn tugent vil breit, er ist der wunne so sat, so birn wir also gemeit – but inflected (pronominal) forms still occur: die dâ wunde lâgen ‘those who lay wounded’, sîn jâmer wart so vester ‘his misery became so great’, daz nie kein tag so langer wart. The pronominal (inflected) forms do not appear in this function later than Early New High German. In a Bible translation from 1470, the pronominal forms are used: der stirbet starker und gesunder. Luther, however, uses the nominal (uninflected) forms frisch and gesund [57].

Adverbial function – adjectives and adverbs

In modern German, the adjective is uninflected in its adverbial function. It is either an independent adverbial (e.g., sie singt gut) or an adverbial attribute of another adjective (ein schön begabtes Kind; ein wirklich großer Erfolg). From a diachronic point of view, however, this is only a modified truth, as the adjective in its adverbial function originally had an ending, which has today simply disappeared by apocope. In Old High German, the adjective in its adverbial function added the suffix -o to the adjective stem, for example, lango (< lang), scôno (< sconi), mâhtigo (< mâhtig), snëllo (< snëll). Adjectives ending in -i (ja-/jô stems) have an umlaut, when possible, but the adverb does not: for example, adverb harto (adjective herti), adverb fasto (adjective festi), MHG adverb schône (< adjective schoene). This also shows that Modern German schon and schön are diachronically the same word, even if the meaning has changed in the meantime. The origin of -o is not clear [58], however some researchers assume that it may be a fossilized ablative [59]. In Middle High German, -o is weakened to -e (schwa). Already in Middle High German, this -e is in many cases apocopied. In Early New High German, adverbs are sometimes with, sometimes without -e [60]. Even Opitz has forms such as leichte and geschwinde, but the form with -e later disappears so that the adjective in New High German can be said to be uninflected in adverbial use, at least from a synchronic point of view. And, strictly speaking, it makes more sense not to talk about ‘inflection’ of the adjective but about ‘derivation,’ so that -o (later -e) is a derivational suffix, and that the word class is then not an adjective but an adverb [61]. However, there is an osmosis between the word classes adjective and adverb. Whereas in Old High German and Middle High German it makes sense to call the o-forms adverbs, in New High German it makes more sense to speak of adjectives in adverbial function due to the similarity in form. Some researchers refer to the o-forms as adjectival adverbs, emphasizing the adjectival basis and the osmosis between the word classes [62].

The use of the strong and weak declension

All adjectives can be inflected according to both the strong and the weak declension. The morphology of the two declensions and the syntactic function of the adjectives have been described above. But when is the strong and weak declension used? And has its use changed throughout the history of German? In the following, I will try to briefly answer these questions and explain some of the general principles on which linguistic change is based regarding the declensions.

The use of the two declensions has not always been regulated as it is today. In general, the development is based on a tension between some often-conflicting principles:

• A functional-semantic versus a mechanical-morphosyntactic principle: Is the choice of one of the two inflections determined by an ontological reference outside the language system itself? In other words: Do the declension types have a referential semantics? Or does it rather depend on a closed linguistic mechanics operating within the language system itself?

• ‘Monoflexion’ versus ‘polyflexion’: Linguistic economy generally seems to be a major focal point in the development of German. For example, it is an expression of economy and linguistic efficiency to express a given grammatical category clearly only once in a nominal phrase, which – as already described – consists of three components: a determiner, an adjective, and a noun.

• Language use and language normalization: To what extent have normative grammarians controlled the language, and to what extent has it developed freely?

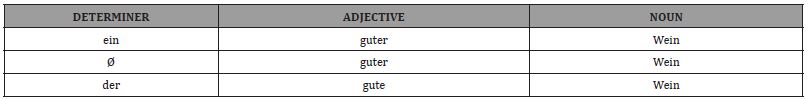

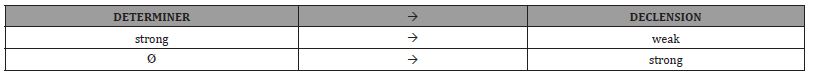

Let’s take modern German as a starting point. The case of the noun phrase is governed by the syntax of the sentence (clause function). Number is governed referentially: Does the speaker or writer want to express something in singular or plural? Gender is governed by the noun chosen. But how, then, is one of the two declension types chosen? The principle is simple [63]. If the determiner is strong, weak declension is chosen. If the determiner is Ø – that is, if the determiner ends in -Ø or there is no determiner at all – strong declension is chosen.

Table 13:

The order is based on a principle of firstness: The strong suffix must appear in the first possible place.

Definitions:

• Strong: The endings of the demonstrative pronoun dieser (however, the strong adjective conjugation has the ending -en in genitive singular masculine and neuter, where the pronoun has -es)

• The weak adjective conjugation is described above (either -e or -en)

• Ø is either no determiner or a determiner whose ending is -Ø (e.g. ein-Ø).

Determiners that are only strongly inflected are: the definite article and the pronouns aller, dieser, jeder, jener, solcher, and welcher. Determiners that have either Ø or a strong ending are the indefinite article, the possessive pronouns, and kein. These rules are described in most grammar books. However, grammatical didactics differ slightly in that some grammars choose to write the endings according to the determiners, for example {ein-Ø > strong} versus {ein-en > weak}. There is nothing wrong with writing down this mixture of strong and weak endings, but it is not, as the morphological section above has shown, an independent declension. In my opinion, it causes confusion when some grammarians call this transcription a ‘mixed declension’. Didactically speaking, however, it is, first, important not only to teach inflectional endings but to remember to explain the general principles. I won’t go into the didactics of adjective declensions here but will return to the topic in another article.

In summary, the choice of adjective declension in modern German is primarily characterized by a mechanical-syntactic principle, in which the determiner is the decisive factor, and by the tendency to monoflexion and language control. However, the system is, at the same time, characterized by a functionalist principle of firstness, language economy, and the syntactic interaction of the nominal phrase. Whether the speaker wants to express something definite or indefinite is reflected in the choice of the determiner rather than the adjective declension itself.

Let’s rewind time to the oldest form of German: Old High German. In Old High German, the definite and indefinite articles are not yet grammaticalized but are derived from the demonstrative pronoun and the number word ein, respectively [64]. Thus, in some cases, the nominal phrases consist of adjective and noun alone. There is an assumption that the weak inflection in Proto-Germanic was used to mark definiteness, while the strong inflection was used to mark indefiniteness. For example, definiteness is to indicate a definite person or thing, one that has been or is about to be mentioned. Indefiniteness refers to less definite or familiar persons or things [65]. The starting point in choosing adjective declension in Proto-Germanic depends on it having a referential semantic. There is a hypothesis in the research that the weak endings themselves were the original carriers of definite meaning, and the strong endings originally ‘meant’ indefinite [66]. However, it is not clear whether the system was really clear-cut outside the Scandinavian languages [67]. The difference still exists in Danish, for example: En god historie (strong declension: indefinite) ‘a good story,’ but den gode historie ‘the good story’ (weak declension: definite) [68].

There seems to be no full consensus in the research literature about the situation in Old High German. Braune states that the use of the two declension types is syntactically conditioned [69], as does Dal. She does point out that in the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, the weak form is often without a determiner and denotes commonly known or discussed concepts [70]. Helm & Ebbinghaus state that the n-inflection “originally” served for individualization without, however, specifying what is meant by “originally” [71]. Delbrück states that the weak adjective is the definite form in Proto-Germanic [72]. Paul/Wiehl/Grosse state that the strong inflection is used to denote indefinite quantities in Gothic [73]. However, Dal adds that this usage has declined rapidly in Old High German. Lockwood writes that Old High German guot(êr) man meant ‘a good man’ – i.e., any good man – in contrast to guoto man, which meant a definite good man. However, he emphasizes that the example guoto man is not actually found in the texts but is constructed by himself, as it was “convenient to construct theoretically the phrase guoto man to illustrate the original function of the weak adjective.” He stresses that actual relics of this oldest syntactic stage are only occasionally found in association with the name of a deity: cot almahtîco ‘God almighty’ (Wessobrunner Prayer). Dal writes the same and mentions an example from Isidor: bi himilischin gote [74]. The only and most radical advocate of the semantic principle being consistently implemented in Old High German are Stricker, Bergmann, et al., who write without any reservation that adjective declensions in Old High German were used according to the semantic principle, and that the strong declension is used in indefinite environments. They claim that this semantic rule was not replaced by a morphological rule of form until Middle High German [75]. Bergmann, Moulin & Ruge write, with some caution like Törnqvist, that Old High German shows tendencies towards semantic regulation, but that the distribution of strong and weak inflection is not strictly regulated [76].

All in all, Stricker, Bergmann et al. seem to stand alone in their assertion that the semantic principle is the guiding principle in Old High German. It is of course clear that in cases where the definite article is determiner, the weak inflection expresses definiteness, but there are just as many examples where an inflected ein is determiner and the weak inflection thus expresses indefiniteness. Just look at the few examples above in the morphology section: Indefinite article + weak inflection in uf einemo blanchen ross (N) and definite use of the strong inflection in themo unûbremo geiste (T) and sinan einegan sun (O).

If we disregard Stricker/Bergmann et al.’s radical claim that the choice of adjective declension in Old High German was based solely on the semantic principle, with the assumption of a dichotomy that strong inflection always expresses an indefinite, and weak inflection a definite content, the picture that emerges shows Old High German in a tension between a semantic and a syntactically controlled principle, which is linked to the fact that the language is developing in a more analytical direction. There are tendencies towards an article usage that has not yet been fully grammaticalized, and that definiteness oscillates in the tension between article and adjective. It is evident that the choice of adjective inflection in Old High German should be the subject of a systematic study that also distinguishes between examples with and without determiner

In Middle High German and Early New High German, there is a tendency towards formal-syntactic regularization, but it is not consistently implemented [77]. Some grammars point out the Modern German principle of strong determiner > weak adjective declension; Ø > strong declension is also prevalent as a tendency in Middle High German and Early New High German [78]. This is undoubtedly true, but there are also many examples that show the opposite, indicating a large variance in the use of strong and weak inflection [79]:

• Middle High German: der listiger man, des ganzes apfels halber teil, disiu richiu kind, ir bestiu vreude, an sîme rôtem helme, in einem schoenem brunnen, die zwêne küene man, sus sprach er zuo der guoter [80].

• Early New High German: der genantir lêrer, ze ainer gantzzer warheit, der vordampter, hochmutiger, schalckhaftiger heide, die swanger frauwen [81].

Stedje briefly notes that the current regulation is said to originate from Gottsched [82]. In the first centuries of New High German, however, the principle of monoflection is far from being systematically implemented, for example: in dem allerenstlichem Ernst, dieser toter Hund (Lessing).

Strong inflection on -e after strong determiner in nominative and accusative plurals is particularly frequent [83]:

• die vergangne Zeiten (Goethe), durch die tausendfache Stufen (Schiller), die vertilgte Hugenotten (Schiller), diese Gelehrte (Lessing), diese schwarze Tücher (Wieland), über diese heitere Darstellungen (Goethe), für meine noch zu schwache Schultern (Goethe), jene große und gute Menschen (Herder), jene überspannte Tätigkeiten (Herder), keine höhere Schönheiten (Lessing), an keine andere Schranken (Schiller), die dumme Dänen (Danish saying attributed to Germans since the mid-eighteenth century).

Conclusion and Further Research

This article has discussed the linguistics of the German adjective declensions over a period of approximately 1,275 years: its morphology and syntax from Old High German to the present.

With regard to the morphology, we have seen that inflectional paradigms have changed from a relatively large inventory of endings to a smaller inventory with a correspondingly higher degree of homonymous forms, partly due to syncretism as a result of phonological change. The weak adjectival declension in particular is characterized by homonymy, with a total of only two endings: -e and -en. Furthermore, we have seen that the strong declension consists of both nominal (uninflected) and pronominal (inflected) forms. The pronominal forms correspond to the endings of the demonstrative pronoun. The nominal (uninflected) forms seem particularly frequent in Early New High German, where, however, they can be difficult to distinguish from other forms which are uninflected due to e-apocope, analogy and ecthlipsis. They partly stick to the nineteenth century, but in modern German they are only found in some established proverbs and phrases.

Regarding the syntactic functions, we have seen that in Old High German the adjective could be inflected in all functions. After a long process of linguistic change, the prototypical rule in modern German is that the adjective is inflected when it is part of a nominal clause and uninflected when it is not, i.e. predicative or adverbial.

With regard to the use of the strong and weak declension, the starting point was the semantic-functional principle: in Proto- Germanic, the weak declension marked definiteness, while the strong declension marked indefiniteness. This distribution seems to disappear with the grammaticalization of the definite and indefinite article, but the situation in Old High German should be investigated more thoroughly. The distribution of strong and weak adjective declension from Old High German, and up to the first centuries of New High German is characterized by a certain arbitrariness and navigates, at least to some extent, in the tension between a semantic- functional and a syntactic-mechanical principle.

From the later part of New High German, the distribution principle is purely syntactic-mechanical, and a principle of monoflexion can be observed – although not fully realized: that is, the strong ending in a nominal phrase only occurs once. Based on the principle of firstness, the strong ending should occur as early as possible in the nominal phrase. The pronominal endings are the primary carrier of the grammatical content. In modern German, the development towards monoflexion is not yet complete, as new tendencies can be seen, for example that only the first adjective is strongly inflected in the case of parallel adjectives: in gepflegtem privatem Rahmen > in gepflegtem privaten Rahmen [84].

The original Proto-Germanic declension classes have, as the Swiss linguist Rudolf Hotzenköcherle once put it, undergone eine Schrimpfung [‘a shrinkage’] [85]. We have already seen how the adjective in English has a very simple morphology, as in modern English it exists in only one form that is not inflected (e.g. red). Hotzenköcherle estimates that since Proto-Germanic, the German language has travelled about half the distance that English has travelled.

One might wonder whether German would have gone further down this path if normative grammarians had not, for example, regulated and preserved the adjective declensions and their usage. Could the uninflected forms that peaked in Early New High German have formed the basis for a simpler inflectional system? It is, of course, difficult to know, but an indication can perhaps be given by the German varieties outside the German-speaking area. These are not subject to a normalized standard, but have developed more freely, and been subject to language contact. What does the declension of adjectives look like in these varieties? This will be investigated in a future thesis.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Braune W (141987) Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer; Braune W, Reiffenstein I (152004): Althochdeutsche Grammatik I. Laut- und Formenlehre. Niemeyer; Curme GO (21964) A Grammar of the German Language. Ungar Publishing Co.; Jørgensen P (1963) German Grammar. New York University Press; Moser V (1909) Historisch-grammatische Einführung in die frühneuhochdeutschen Schriftdialekte. Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses; Paul H (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer; Penzl H (1984) Frühneuhochdeutsch. Lang; Schrodt R (2004) Althochdeutsche Grammatik II. Syntax. Niemeyer; Reichmann O, Wegera KP (1993) Frühneuhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer; Moser H, Stopp H, Besch W (eds.) (1991) Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Vol. 6: Solms HJ, Wegera KP Flexion der Adjektive. Winter; Weinhold K, Ehrismann G, Moser H (151968) Kleine mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Braumüller.

- Bergmann R, Moulin C, Ruge N (2011) Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch. Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; Chambers WW, Wilke JR (1970) A Short History of the German Language. Methuen; Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer; Kluge F (21925) Deutsche Sprachgeschichte. Werden und Wachsen unserer Muttersprache von ihren Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Quelle & Meyer; Lockwood WB (1968) Historical German Syntax. Clarendon; von Polenz P (1994) Deutsche Sprachgeschichte. De Gruyter; Schmidt W. (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel; Stricker S, Bergmann R, Wich-Reif, C, Kremer A (22015) Sprachhistorisches Arbeitsbuch zur deutschen Gegenwartssprache. Winter; Waterman J T (1966) A History of the German Language. With Special Reference to the Cultural and Social Forces that Shaped the Standard Literary Language. University of Washington Press; Wells CJ (1985) German: A Linguistic History to 1945. Oxford University Press.

- Grimm J (1819) Deutsche Grammatik, vol. IV, Dieterichsche Buchhandlung: 549ff.

- Bergmann R, Moulin C, Ruge N (2011) Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch. Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 117; Waterman J T (1966) A History of the German Language. With Special Reference to the Cultural and Social Forces that Shaped the Standard Literary Language. University of Washington Press, 31.

- Helm K, Ebbinghaus EA (51980) Abriss der mittelhochdeutschen Grammatik, Niemeyer: 76.

- Van de Velde F, Sleeman P, Perridon H (2013) The Adjective in Germanic and Romance. Development, Differences and Similarities, in Sleeman P, van de Felde F, Perridon H 2013 (eds.): Adjectives in Germanic and Romance, Linguistics Today, vol. 212: 2; Prokosch E (1939) A Comparative Germanic Grammar. Linguistic Society of America: 259.

- Mettke H (51983) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik VEB Bibliographisches Institut: 156f.

- Chambers WW, Wilkie JR (1970) A Short History of the German Language. Methuen: 125.

- Lockwood WB (1968) Historical German Syntax. Clarendon Press 1968: 39ff.

- Moser H, Stopp H, Besch W (eds.) (1991) Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Vol.6: Solms HJ, Wegera KP Flexion der Adjektive. Winter: 57ff.

- Waterman J T (1966) A History of the German Language. With Special Reference to the Cultural and Social Forces that Shaped the Standard Literary Language. University of Washington Press: 33.

- Darski J (1979) Die Adjektivdeklination im Deutschen, in Sprachwissenschaft 4: 190-205; Moser H, Stopp H, Besch W (eds.) (1991) Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Vol.6: Solms HJ, Wegera KP Flexion der Adjektive. Winter: 57ff.

- Bergman R, Pauly P (31985) Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch. Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Tübingen: 202.

- Lockwood WB (1968) Historical German Syntax. Clarendon Press 1968: 42-43.

- Stricker S, Bergmann R, Wich-Reif, C, Kremer A (22015) Sprachhistorisches Arbeitsbuch zur deutschen Gegenwartssprache. Winter: 148.

- Jakobsen LF, Olsen J (41981) Den moderne grammatiks grundbegreber. Lingvistik 1 [The Basic Concepts of Modern Grammar. Linguistics 1]. Copenhagen University: 3; Mogensen JE (1999): [Review article] Ulla Björnheden Zum Vierkasussystem des Mittelniederdeutschen, Studia Neophilologica 71: 110-111.

- Schmidt W (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel: 209.

- Braune W, Eggers H (141987) Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 216.

- Braune W, Eggers H (141987) Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 216.

- Jakobsen LF, Olsen J (41981) Den moderne grammatiks grundbegreber. Lingvistik 1 [The Basic Concepts of Modern Grammar. Linguistics 1]. Copenhagen University: 32.

- Braune W, Eggers H (141987) Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer.

- From Notker (N), Otfrid (O), Tatian (T) and Ludwigslied (L).

- Strong declension, masculine plural nominative and accusative.

- Weak declension, singular genitive and dative masculine and neuter.

- Lockwood WB (1968) Historical German Syntax. Clarendon Press 1968: 38; Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage, Niemeyer: 62; Schmidt W (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 61; Kluge F (1924) Deutsche Sprachgeschichte. Werden und Wachsen unserer Muttersprache von ihren Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Quelle & Meyer.

- Braune W, Eggers H (141987) Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 288.

- Schmidt W (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel: 264; Mettke H (51983) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik VEB Bibliographisches Institut: 157.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 198 A. 3.

- Mettke H (51983) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik VEB Bibliographisches Institut: 154; Törnqvist N (1974) Zur Geschichte der deutschen Adjektivflexion. In Neophilologische Mitteilungen, 72:2: 323.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 198; Weinhold K, Ehrismann G (1968) Kleine mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Stuttgart: Braumüller, § 113.

- Stedje A (72007) Deutsche Sprache gestern und heute. Fink: 141ff.

- Mettke H (51983) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik VEB Bibliographisches Institut: 32.

- Reichmann O (1986) Lexikographische Einleitung, in Anderson RR, Goebel U, Reichmann O (eds.) Frühneuhochdeutsches Wörterbuch. De Gruyter: 31ff.

- Winge V (1978) Einige Betrachtungen zur sogenannten Pluralumwälzung im Deut¬schen. Kopenhagener Beiträge zur germanistischen Linguistik 10: 33-42; West N (2001) Numerusprofilierung oder Numerusverundeutlichung? Eine synchrone und diachrone Untersuchung der substantivischen Pluralbildung im Frühneuhochdeutschen. Unpublished Master thesis, University of Copenhagen, 135 pp.; Stedje A (72007) Deutsche Sprache gestern und heute. Fink: 168.

- Stedje A (72007) Deutsche Sprache gestern und heute. Fink: 164f.

- Stedje A (72007) Deutsche Sprache gestern und heute. Fink: 141ff.

- Reichmann O, Wegera KP (1993) Frühneuhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer; Moser H, Stopp H, Besch W (eds.) (1991) Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Vol.6: Solms HJ, Wegera KP Flexion der Adjektive. Winter.

- Moser H, Stopp H, Besch W (eds.) (1991) Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Vol. 6: Solms HJ, Wegera KP Flexion der Adjektive. Winter: 81.

- Reichmann O, Wegera KP (1993) Frühneuhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 199.

- Reichmann O, Wegera KP (1993) Frühneuhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 190 & 199; Penzl H (1984) Frühneuhochdeutsch. Peter Lang: 122, Moser V (1909) Historisch-grammatische Einführung in die frühneuhochdeutschen Schriftdialekte. Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses: 184.

- Moser V (1909) Historisch-grammatische Einführung in die frühneuhochdeutschen Schriftdialekte. Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses 184; Penzl H (1984) Frühneuhochdeutsch. Peter Lang: p 122, Lockwood WB (1968) Historical German Syntax. Clarendon Press 1968: 38.

- Moser H, Stopp H, Besch W (eds.) (1991) Grammatik des Frühneuhochdeutschen. Beiträge zur Laut- und Formenlehre. Vol. 6: Solms HJ, Wegera KP Flexion der Adjektive. Winter: 80; Schmidt W (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel: 337.

- Reichmann O, Wegera KP (1993) Frühneuhochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 194.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 64.

- Schmidt W (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel: 338; Törnqvist N (1974) Zur Geschichte der deutschen Adjektivflexion. In Neophilologische Mitteilungen, 72:2: 323.

- Bergman R, Pauly P (31983) Neuhochdeutsch. Ein Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der deutschen Gegenwartssprache. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 54.

- Chambers WW, Wilkie JR (1970) A Short History of the German Language. Methuen: 141.

- Mogensen JE (2002) Die Grammatik der Adjektive im deGruyter Wörterbuch Deutsch als Fremdsprache, in Wiegand HE (ed.) Perspektiven der pädagogischen Lexikographie des Deutschen II, Lexicographica. Series Maior 110, Niemeyer: 99; Bepler H, Mogensen JE, Schjørring G (2000) Tysk Basisgrammatik. Gyldendal: 36; Helbig G, Buscha J (141991) Deutsche Grammatik. Ein Handbuch für den Deutschunterricht: Langenscheidt: 554.

- Schrodt R (2004) Althochdeutsche Grammatik II. Syntax. Niemeyer: 28.

- Lockwood WB (1968) Historical German Syntax. Clarendon Press 1968: 38.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 62.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 62.

- Dürscheid C (2002) “Polemik satt und Wahlkampf pur” - Das postnominale Adjektiv im Deutschen. In: Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 21/1: 57-81.

- Mogensen JE (1994) Kein Deutsch ohne Mühe. Munksgaard: 248.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 63.

- Henzen W (31965) Deutsche Wortbildung. Niemeyer: 157.

- Henzen W (31965) Deutsche Wortbildung. Niemeyer: 166.

- Moser V (1909) Historisch-grammatische Einführung in die frühneuhochdeutschen Schriftdialekte. Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses: 152.

- Bergmann R, Moulin C, Ruge N (2011) Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch. Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 120; Henzen, W (31965) Deutsche Wortbildung. Niemeyer: 157.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 64; Bergmann R, Moulin C, Ruge N (2011) Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch. Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 120.

- Mogensen JE (2002) Die Grammatik der Adjektive im deGruyter Wörterbuch Deutsch als Fremdsprache, in Wiegand HE (ed.) Perspektiven der pädagogischen Lexikographie des Deutschen II, Lexicographica. Series Maior 110, Niemeyer: 92.

- Schrodt, R (2004) Althochdeutsche Grammatik II. Syntax. Niemeyer: 24ff.

- Chambers WW, Wilkie JR (1970) A Short History of the German Language. Methuen: 140.

- Harbert W (2007) The Germanic Languages. Cambridge University Press, 131, and Braunmüller K (2008) Observations on the origin of definiteness in ancient Germanic, Sprachwissenschaft 31: 351-448.

- Van de Velde F, Sleeman P, Perridon H (2014) The Adjective in Germanic and Romance. Development, differences and similarities. In Sleeman P, Van de Velde F, Perridon H (eds.) Adjectives in Germanic and Romance. John Benjamins: 4.

- Olander T (2024) Dansk fra nutiden til stenalderen. U Press: 108.

- Braune W (141987) Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Niemeyer: 215.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 64.

- Helm K, Ebbinghaus EA (51980) Abriss der mittelhochdeutschen Grammatik, Niemeyer: 30.

- Delbrück B (1909) Das schwache Adjektiv und der Artikel im Germanischen. Indogermanische Forschungen 26(1): 187-199.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Tübingen: 356.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 64.

- Stricker S, Bergmann R, Wich-Reif, C, Kremer A (22015) Sprachhistorisches Arbeitsbuch zur deutschen Gegenwartssprache. Winter: 154.

- Bergmann R, Moulin C, Ruge N (2011) Alt- und Mittelhochdeutsch. Arbeitsbuch zur Grammatik der älteren deutschen Sprachstufen und zur deutschen Sprachgeschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 120; Törnqvist N (1974) Zur Geschichte der deutschen Adjektivflexion. In Neophilologische Mitteilungen, 72:2: 322.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Tübingen: 356.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Tübingen, 196.

- Mettke H (51983) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik VEB Bibliographisches Institut: 217.

- Paul H, Wiehl P, Grosse S (231989) Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Tübingen, 356, and Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 64.

- Schmidt W (71996) Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Ein Lehrbuch für das germanistische Studium. S. Hirzel: 337.

- Stedje A (72007) Deutsche Sprache gestern und heute. Fink: 180.

- Dal I (31966) Kurze deutsche Syntax auf historischer Grundlage. Niemeyer: 64.

- Moulin-Fankhänel C (2000) Varianz innerhalb der Nominalgruppenflexion. Ausnahmen zur sogenannten Parallelflexion der Adjektive im Neuhochdeutschen. In Germanistische Mitteilungen, Zeitschrift für deutsche Sprache, Literatur und Kultur. Brüssel: 76.

- Hotzenköcherle R (1962) Entwicklungsgeschichtliche Grundzüge des Neuhochdeutschen. In Wirkendes Wort 12: 321-331.

-

Jens Erik Mogensen*. The German Adjective: The History of Its Declensions and Their Usage from the Beginning to the Present. Iris J of Edu & Res. 5(1): 2025. IJER.MS.ID.000603.

-

Historical linguistics, Morphology, Syntax, Semantics, Adjectives, Linguistic change

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.