Mini Review

Mini Review

Recognizing the Importance of Empathy and Humanity from Aesthetic and Social-Psychological Perspectives to Promote Sustainability in Fashion Design Education

Ching-Yi Cheng*

Department of Textiles and Clothing, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan

Ching-Yi Cheng, Associate Professor, Department of Textiles and Clothing, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan

Received Date:May 31, 2024; Published Date:June 05, 2024

Abstract

A good designer for the future will not only need to have traditional academic knowledge and technical skills but also need to detect the problems and issues behind the social and cultural context, build up the understanding, and know how to design products that meet the needs of individual or society for the improvements of quality in human life. This paper delves into the significance of integrating empathy and humanity by proposing a holistic model for teaching sustainable fashion design. It highlights how emphasizing aesthetic and social-psychological values in the fashion design curriculum can lead to more ethical and responsible practices in the sustainable fashion industry, extending beyond ecological or environmental concerns.

Keywords:Sustainability; Apparel Design; Sustainable Fashion Education; Humanities; Empathy; Aesthetics; Social Psychology

Introduction

Design with a Good Cause Behind: Sustainability

As society changes rapidly and the future is highly unpredictable due to globalization, it is important to rethink the role future fashion designers will play and what new skill sets will be needed for the evolving global fashion industry [1]. A good designer for the future will not only need to have traditional academic knowledge and technical skills but also need to detect the problems and issues behind the social and cultural context, build up the understanding, and know how to design products that meet the needs of individual or society for the improvements of quality in human life. It is necessary for an evolving education that creates socially engaged curricula and design projects for design students to become future agents of change as the world demands better solutions for concerns such as economic, social, and ecological sustainability [1,2]. Sustainability is apparently the key to driving change and revolutionizing the fashion industry. However, fashion designers encounter both internal (personal) and external (organizational) challenges when implementing sustainable design practices, such as insufficient consensus and knowledge regarding sustainable design and integrating sustainability into fashion through designled approaches [3]. Educating the next generation of designers on sustainable apparel design is imperative, with fast fashion seems to be taking over the industry and immersing our daily lives. This paper aims to provide critical thinking and a conceptual framework as a guideline for aspiring sustainable fashion design in education.

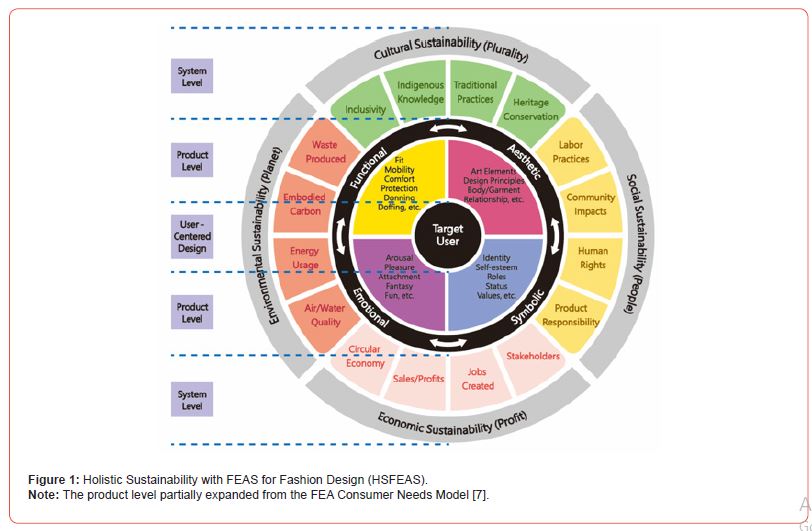

Sustainability was originally defined from the “triple bottom line” approach, which refers to people (society), planet (environment), and profit(economy). More recently, cultural sustainability has become a crucial issue and is considered the fourth pillar of sustainability, along with social, economic, and environmental concerns [4]. It includes society’s tangible and intangible aspects (e.g., social structures, literature, religion, myths, beliefs, behaviors, entrepreneurial practices, technology use, and artistic expression). It involves preserving cultural beliefs and practices, safeguarding cultural heritage, and addressing whether any culture will endure in the future [5]. Besides the systems level of cultural considerations, the product level of aesthetics was added to expanded traditional sustainability models [6]. This paper proposes a holistic framework with a user-centered design approach of FEAS (i.e., Functional, Emotional, Aesthetic, and Symbolic) at the product level and the 4Ps (i.e., People/Society, Planet/Environment, Plurality/Culture, and Profit/Economy) at the system level of sustainability for sustainable fashion design (see Figure 1).

This Holistic Sustainability with FEAS (HSFEAS) model expands the wildly used FEA (i.e., Functional, Expressive, and Aesthetic) Consumer Needs Model for apparel design [7,8] to FEAS by replacing “Expressive” with “Symbolic” and adding “Emotional” aspect to the apparel design framework since the experiential aspects of consumption, such as fantasies, feelings, and fun, play important roles in consumers’ purchase decisions [9]. Fashion designers prioritize the emotional and affective elements, a focus that has garnered widespread recognition within the fashion industry and academic research [10,11].

As sustainability has become increasingly intertwined and gained recognition worldwide, the designer’s role is evolving due to the new demands of environmentally friendly, emotionally compelling, ethically satisfying, and meaningful products. The beneficence intention, compassionate purpose behind fashion design, and ethical content are essential. Sustainable design would be meaningful if initiated with empathy and navigated with humanity towards solidarity and harmony between humans and nature. Ultimately, design education should not only aim to foster individuals who can design mechanically with good skills without a good heart behind and humanity literacy. This paper highlights user-centered design with some insights on empathy and humanity from aesthetic and social-psychological aspects to enhance teaching sustainable fashion design beyond frequently mentioned functional, technical, instrumental, and environmental aspects.

Design with a Heart: Motivated by Empathy

Sustainable clothing design aims not solely to generate profit or gain social approval but to empathize and care. Empathy is defined as “the inner experience of sharing in and comprehending the momentary psychological state of another person.” [12]. Designers design sustainably because of the desire to help, to do better, or to do good – to behave ethically, and the root motivation for ethics is empathy [13]. Empathy is the initial step in design thinking, involving a human-centered approach to problem-solving rather than being technology- or organization-centered, which has become essential for successful product design [14].

The designer’s ethical response is more integrated and holistic with empathy. However, empathetic understanding does not always happen automatically [15]. To evoke the development of empathy, some in-class strategies for teaching empathy involve training students to immerse themselves in another person’s experience and empathize with an image [13]. Through the learning activities, students are expected to be able to speculate on and discuss the potential experiences, feelings, and thoughts of other people. Combining empathy and creativity may ensure better and more marketable solutions for clients or consumers [16]. The affective method can unlock material fashion by emphasizing the embodied experiences, feelings, and emotions crucial to individuals’ connection with fashion [10]. The affective education approach helps fashion design students develop empathy and understand that the relationship between design products and users should extend beyond just encouraging the user to purchase.

Stepping out of the classroom, service learning is considered an efficient way for design students to develop empathy. Fashion design students develop empathy through professional activities such as service design, social design, community engagement, recognizing the help of other people and their surroundings, and changing egocentric thinking [17]. Fashion education using the “learning by doing” method, such as service learning, besides intellectual growth, can enhance students’ self-growth (e.g., self-affirmation, confidence, sense of responsibility, patience, change of perspective), interpersonal growth (e.g., communication, leadership, caring, empathy), stimulate their social concern, and enhance the sense of responsibility to society (e.g., sensitivity to social needs and a sense of responsibility to serve the public), positive subjective emotions (e.g., happiness, love/warmth, contentment, interest), and gratitude for what happens in their daily lives [18]. Students gain social-psychological empowerment after engaging in service learning [19], experience a positive transformation process, broaden their horizons, and become agents and power of social change [20]. Participating in service learning has ongoing benefits for life development after college graduation [21,22]. These include transforming the sense of meaning in life, social participation, career path, leadership, gratitude, and happiness. Sustainable fashion design education based on empathy has a positive and longterm impact on students’ self-growth and future life development, leading to positive life-long success in fashion careers and lives for a sustainable future.

Once students have developed a mindset that is initiativedriven, empathetic-motivated, and focused on beneficence, HSFEAS can be followed as a guideline throughout the fourstage creative fashion design process, which includes problem identification, conceptualization/idea generation, prototype/ design development, and solution/evaluation as suggested by scholars [23]. According to HSFEAS, fashion design students can analyze their target clients’ physical, aesthetic, psychological, and social-cultural needs. This involves determining the clients’ functional, emotional, aesthetic, and symbolic aspirations in fashion while considering sustainability’s four aspects (i.e., People/Society, Planet/Environment, Plurality/Culture, and Profit/Economy) (see Figure 1).

Enhancing Aesthetic Value on Sustainable Fashion Design

Since sustainable fashion is usually interchangeable with eco and green fashion and emphasizes environmental issues in the fashion industry, the fashion design curriculum seems more likely to involve materials (reuse, recycle, reduce) and functionality (physical needs). Most design tools (e.g., Considerate Design, Cradle to Cradle Apparel Design, Higg Index Material Sustainability Index, Nike Making App) the fashion industry provides for improving and developing sustainable fashion assess the environmental impact of materials used in apparel products or particular designs and production [24,25]. However, paying too much attention to the functional and environmental aspects of clothing products while overlooking the aesthetic, emotional, and symbolic aspects of expression may result in products that could not attract consumers and cannot be sold successfully. In consumer purchasing decisions, general clothing products’ aesthetics symbolism plays a key role [26,27], and even for smart clothing [28] and wearable technology clothing [29]. These findings suggest that in fashion design, it is essential to shift technical concerns to a user-centered and designled approach, emphasizing aesthetically appealing design features across product categories. When designing for sustainability in fashion, it’s important to consider an individual’s aesthetic experience [30].

Empowering Social-Psychological Wellbeing on Sustainable Fashion Design

Although sustainable fashion refers not only to environmentally but also ethically conscious design methods or fashion production, more focus is on solving the negative impact of materials and the production of fashion on the environment than on the well-being of fashion laborers and consumers as human beings. With the awareness and caution about fashion’s negative impact on body image (e.g., the relationship between fashion and eating disorders) [31,32] and depression [33], the positive psychology approaches to enhance mood [34] and empower social-psychological wellbeing [35] in fashion design are essential for holistic sustainability. Fashion was found to be a valuable source of positivity in people’s lives. Besides individuals employed clothing practices as a powerful technique/skill to negotiate selfhood, build up confidence, connect with the body (body image), role play, and social interaction, etc. [36,37], clothing can also help individuals feel happiness, uplift emotion, or maintain a positive mood as mentioned in the concept of “dopamine dressing” [38]. Highlighting the social-psychological benefits of sustainable products also positively impacts consumers’ attitudes toward green apparel, encouraging purchase behavior [39].

Fashion design aims to create pleasurable user experiences and meaningful memories, enhancing well-being [40], fostering a strong attachment to clothing, and extending garment lifespan for sustainability [41]. A collaborative design that evokes in-depth emotions and matches consumers’ attachment attributes and preferences could obtain longer lifespans for fashion products [11]. Other than designing brand-new fashion products, adopting an upcycling or redesign approach to enhance the functional and aesthetic properties of used clothing can also foster a deep relationship and emotional connection between the wearer and apparel [42,43], thus increasing the clothing’s longevity while reducing waste. Creating emotional attachments between the wearer and the clothes can be a valuable way to prevent fashion disposal, going beyond FEA (function, aesthetics, and expression) to approach environmental sustainability from a social-psychological perspective.

Embedding Humanity for Common Good on Sustainable Fashion Design

Humanities education aims to develop students’ understanding of human culture and enhance their ability to make ethical decisions, providing a strong foundation for a career in fashion design. Fashion educators have recognized social change and pointed out that today’s design practitioners work to create and think across disciplines and design principles to explore philosophical and critical themes to question the normative body and expand the cultural scope of fashion [44]. Humanistic qualities must be prioritized alongside sustainable fashion design education for diplomas and knowledgeable skills. Studying humanities beyond the production process provides students with critical thinking and a deep understanding of culture, history, society, and human behavior, which is beneficial for creativity and innovation and is a solid foundation for a career in design for ethical fashion [45]. Humanity-centered design based on user-centered design principles prioritizes human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility, and sustainability in product design that focuses on meaningful, inclusive, ethical, and humanitarian and requires empathy and cooperation [46]. The key difference between humancreated designs and AI-generated is the uniqueness and originality rooted in human experiences [47]. In the era of rapid development and the prevalence of AI, fashion design education should cultivate students with love, beneficence, and humanistic literacy rather than machines with excellent design skills.

Conclusion

It is necessary and important for fashion designers to consider economic, social, ecological, and cultural sustainability as their obligation to improve people’s quality of life. Fashion designers can serve as change agents and navigators of the complex world toward harmony between humans and nature for present and future generations. In order to foster designers who care and can understand broader contexts, create innovative new products, and rethink business systems, the philosophies of fashion design education have to be renewed and emphasize holistic sustainability with empathy initiated and humanity embedded. Faculties of fashion design are anticipated to be dedicated to society’s progress and humankind’s advancement, expecting students to be aware of social issues and actively engage in activities that contribute to our society’s and culture’s overall well-being. There is a need for fashion design faculty to embrace new teaching philosophies and methodologies and engage more with professional practices related to sustainability in the future.

Recognizing the development and potential risks associated with AI’s advanced capabilities in design for the fashion industry, a sustainable fashion design curriculum with empathy and humanities embedded would be an essential approach in fashion education. The HSFEAS model proposes an explicitly holistic conceptual framework that guides and steers students’ decisionmaking throughout the design process and practices for sustainable fashion. In addition, HSFEAS provides a potential springboard to systematically develop tools or curricula for sustainable fashion design, further promoting sustainable living and holistic wellness in the long run.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Faerm S (2012) Towards a future pedagogy: The evolution of fashion design education. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2(23): 210-219.

- Grose L, Fletcher K (2012) Fashion & sustainability: Design for change. Hachette UK.

- Hur E, Cassidy T (2019) Perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable fashion design: Challenges and opportunities for implementing sustainability in fashion. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 12 (2): 208-217.

- Hawkes J (2001) The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground Publishing: Melbourne, Australia.

- Macagnan CB, Seibert RM (2023) Culture: A Pillar of Organizational Sustainability. IntechOpen.

- Katzan H (2011) Essentials of service design. Journal of Service Science 4(2): 43-60.

- Lamb JM, Kallal MJ (1992) A conceptual framework for apparel design. Clothing and Textile Research Journal 10(2): 42-47.

- Orzada BT, Kallal MJ (2019) FEA Consumer Needs Model: 25 years later. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 39(1): 24-38.

- Holbrook MB, Hirschman EC (1982) The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research 9(2): 132-140.

- Tienhoven MV, Smelik A (2021) The effect of fashion: An exploration of affective method. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty 12(2): 163-183.

- Wang M, Kim E, Du B (2022) Promoting emotional durability and sustainable fashion consumption through art derivatives design methods. The Design Journal.

- Schafer R (1959) Generative empathy in the treatment situation. Psychoanalytic Quarterly 28: 342-373.

- Thomas S (2009) On teaching empathy. In Parker L, Dickson M (Editors) Sustainable Fashion: A Handbook for Educators. Educators for Socially Responsible Apparel Business, USA.

- Kimbell L (2012) Rethinking design thinking: Part II. Design and Culture 4(2):129-148.

- Barnes A, Thagard P (1997) Empathy and analogy. Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review 36(4): 705-720.

- Myerson J (2001) Overview: The key word is empathy. Show and Symposium, The Helen Hamlyn Research Centre, RCA, London.

- Brown T, Wyatt J (2010) Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review Winter 31-35.

- Cheng CY (2020) Implementation and learning outcomes of service-learning integrating into fashion curriculum. Journal of Service Learning and Social Engagement 3: 15-38.

- Chan K, Ng E, Chan CC (2016) Empowering students through service learning in a community psychology course: A case in Hong Kong. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 20(4): 25-35.

- Crawford P, Kotval Z, Machemer P (2011) From boundaries to synergies of knowledge and expertise: Using pedagogy as driving force for change. In Angotti T, Doble C, Horrigan P (Editors.) Service-learning in design and planning. New Village Press, Oakland, CA, pp.209-221.

- Pritchard K, Bowen BA (2019) Student partnerships in service-learning: Assessing the impact. Partnerships: A Journal of Service-Learning & Civic Engagement 10(2): 191-207.

- Stolley KS, Collins T, Clark P, Hotaling DE, Takacs RC (2017) Taking the learning from service learning into the post college world. Journal of Applied Social Science 11(2): 109-126.

- Watkin SM, Dunne LE (2015) Functional clothing design: From sportswear to spacesuits. Bloomsbury, New York, USA.

- Black S, Eckert C (2012) Considerate design: Supporting sustainable fashion design. In Black S (Editor), The Sustainable Fashion Handbook, Thames & Hudson, London, UK pp. 92-95.

- Kozlowski A, Bardecki M, Searcy C (2019) Tools for sustainable fashion design: An analysis of their fitness for purpose. Sustainability 11: 3581.

- Fiore AM (2010) Understanding aesthetics for the merchandising and design professional. Fairchild Publications.

- Eckman M, Damhorst ML, Kadolph SJ (1990) Toward a model of the in-store purchase decision process: Consumer use of criteria for evaluating women's apparel. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal 8(2): 13-22.

- Hwang C, Chung TL, Sanders EA (2016) Attitudes and purchase intentions for smart clothing: Examining U.S. consumers’ functional, expressive, and aesthetic needs for solar-powered clothing. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 34(3): 207-222.

- Sun D (2019) Wearable technology clothing - the potential to adapt and succeed in fashion retail. Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology 5(4): 193-195.

- Zafarmand SJ, Sugiyama K, Watanabe M (2003) Aesthetic and sustainability: The aesthetic attributes promoting product sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Product Design, 3: 173-186.

- Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK (2002) The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders 31(1): 1-16.

- Castellano S, Rizzotto A, Neri S, Currenti W, Guerrera CS, et al. (2021) The relationship between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms in young women aspiring fashion models: The mediating role of stress. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11(2): 607-615.

- Dubler MLJ (2009) Depression: Relationships to clothing and appearance self‐concept. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 13(1): 21-26.

- Wenderski M, Jung J, Wasilewski J (2023) The use of clothing as a mood enhancer and its effect on mental health in emerging adults in Canada during a global pandemic. ITAA Proceedings, #80. Baltimore, Maryland.

- Suganya S, Rajamani K, Buvanesweri L (2024) Examining the influence of fashion on psychological well-being, investigating the correlation between apparel selections, self-confidence, and mental health. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews 11(1): 118-128.

- Damhorst ML, Miller K, Michelman, SO (2005) The meanings of dress (2nd ed.) New York: Fairchild Publications.

- Lennon SJ, Johnson KKP, Rudd NA (2017) Social psychology of dress. Fairchild Publications.

- Karen D (2020) Dress your best life: How to use fashion psychology to take your look -- and Your Life -- to the Next Level. Little, Brown.

- Rūtelionė A, Bhutto MY (2024) Exploring the psychological benefits of green apparel and its influence on attitude, intention, and behavior among Generation Z: a serial multiple mediation study applying the stimulus-organism-response model. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print.

- Çili S (2023) Personal objects and dress as instruments for anchoring the self, remembering the past, and enhancing well-being. In Memories of dress: Recollections of material identities. Bloomsbury, pp. 23-35.

- Niinimäki K (2013) From pleasure in use to preservation of meaningful memories: A closer look at the sustainability of clothing via longevity and attachment. International Journal of Fashion Design Technology and Education 6(3): 190-199.

- Janigo KA, Wu J, DeLong M (2017) Redesigning fashion: An analysis and categorization of women’s clothing upcycling behavior. Fashion Practice 9(2): 254-279.

- Paras MK, Curteza A (2018) Revisiting upcycling phenomena: a concept in clothing industry. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 22(1): 46-58.

- Burns D (2019) Substantiality and social change in fashion. Fairchild Books, New York.

- Vänskä A (2018) How to do humans with fashion: Towards a posthuman critique of fashion. International Journal of Fashion Studies 5(1): 15-31.

- Russell P, Buck L (2020) Humanity-centred design-Defining the emerging diagram in design education and practice. International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education. Herning, Denmark.

- Lee YK (2022) How complex systems get engaged in fashion design creation: Using artificial intelligence. Thinking skills and creativity 46.

-

Ching-Yi Cheng*. Recognizing the Importance of Empathy and Humanity from Aesthetic and Social-Psychological Perspectives to Promote Sustainability in Fashion Design Education. Iris J of Edu & Res. 3(2): 2024. IJER.MS.ID.000559.

-

Sustainability, Apparel Design, Sustainable Fashion Education, Humanities, Empathy, Aesthetics, Social psychology

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.