Research Article

Research Article

An Orchestration Perspective on Computer-Supported Collaborative Language Learning: A literature Review

Eirini Dellatola1*, Thanassis Daradoumis1,2 and Yannis Dimitriadis3

1Open University of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain

2University of Aegean, Mytilini, Greece

3Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain

Eirini Dellatola, Open University of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain

Received Date: September 08, 2024; Published Date: September 25, 2024

Abstract

The term orchestration has gained much attention in the field of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) in the last decade and many strategies and tools have been proposed to help teachers orchestrate collaborative learning activities in real time. Despite the great interest in the area only few studies have explored the specific needs of orchestrating Computer-Supported Collaborative Language Learning (CSCLL) activities and the unique attributes deriving from the Language Learning (LL) discipline have not been fully investigated yet. Studies in different subjects have highlighted the critical role of orchestration and how it affects students’ attitudes and learning outcome; however, the explicit study of language learning environments is limited. Following a systematic review method, 30 studies are reviewed and indicate how orchestration has been conducted in LL environments and what are the implications regarding students’ motivation, engagement, self-regulation and learning outcome. The findings indicate that research in this area is still in the initial stages and although the first results appear promising, there are several open issues to be addressed. Finally, recommendations for future research are provided and the need for more systematic analyses of the special needs of CSCLL environments is emphasized.

Keywords: Collaborative Language Learning; Computer-Assisted Language Learning; Orchestration

Introduction

Technology has always played an important role in the field of LL and particularly Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) promotes the idea that technology must be an integral part of the LL process and not a mere helpful tool to computerize the traditional, existing methodologies [1,2]. Technology refers both to software and hardware and their combination can offer intriguing possibilities with formal and informal activities, face-to-face and remote interactions among both students to instructors and students to students, selfinstructional courses, and collaborative learning, to name a few. However, all these possibilities lead to the so-called “complex ecosystem of the Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) classroom” in which many complicated issues of management appear [3,4]. This complexity is thought to be the main reason for the significant delay in achieving a pedagogically effective use of technology. It can also partially explain why teachers avoid technology in their classrooms, especially when they deal with complex pedagogies. Teachers face numerous problems such as time pressure, strict curriculum, insufficient infrastructure or even deficiencies in technological skills along with many unpredictable events that may interrupt a regular lecture [5]. Having to deal with complex technology can make matters even worse and add unforeseen interruptions [6,7].

The academic community has claimed that the reasons which prevent full adoption of CSCL in classrooms must be analysed in depth [8-13]. Many opinions have been expressed on this problem and one of the proposed solutions is to look closer at the phenomenon of classroom orchestration. According to the most widely acceptable definition, orchestration examines how a teacher can manage, in real time, multi-layered activities in a multi-constraint context [14], and even though there is a thriving research activity recently, there are still many open questions to be answered [15]. Moving a step forward, some researchers have recently considered orchestration as a “bridge” [16] that can connect the field of Learning Design (LD) with that of Learning Analytics (LA) and lead to the creation of environments that are both pedagogically rooted and usable in authentic situations). Many studies have already explored orchestration in different disciplines [17,18] but research in the language learning field is still scarce [19].

The aim of this article is to perform a systematic review using the set of guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework. This review will focus on existing studies of orchestration in CSCL. Firstly, we will investigate under what forms and modalities the idea of “classroom orchestration” has been used in CSCLL and then using the 5+3 framework [20] we will evaluate the proposed tools and methods. Finally, we will explore the potential of orchestration to address the limited implementation of CSCLL in classrooms. The main research questions are as follows:

RQ1. What types of orchestration strategies have been applied to CSCLL?

RQ2. What are the basic findings about students’ motivation, behavioural and cognitive engagement, and self-regulation in orchestration and CSCLL?

RQ3. What is the impact of orchestration on learning outcomes?

The following section outlines a brief review of previous studies and theoretical perspectives on CSCLL and orchestration. Thereafter, the review methodology and the inclusion criteria are described. Finally, the research questions are addressed and discussed.

Theoretical Background

CSCL is a multi-disciplinary field that combines conceptual frameworks and analytic approaches from many fields, such as education, psychology, computer, and social science [21]. Collaborative learning is not a synonym of students learning in groups but involves groups of learners working together to solve a problem, complete a task or create a product. In a language classroom even a simple practice conversation in the target language could be considered as working together to solve a problem (e.g., overcome unwillingness to communicate), complete a task (e.g., understand and be understood) or create a product (e.g., produce correct language utterances) [22].

When referring to CSCL, not only do we include the use of technology to connect remote students, but also to shape face-toface interactions and create a situation in which two or more people learn or attempt to learn something together [23]. A great variety of collaborative strategies (such as jigsaw, think-pair-share, etc.) have been developed to provide a more systematic and meaningful application of CSCL in class [11,24].

Research has shown that collaboration can offer many advantages to LL, such as motivating students to participate in an environment where they are asked to use their skills to communicate effectively, improving access to shared knowledge and encouraging students to work towards common aims [25-27]. Collaborative learning is considered as one of the most effective instructional strategies in language learning since it “has a ‘social constructivist’ philosophical base, which views learning as construction of knowledge within a social context and which therefore encourages acculturation of individuals into a learning community” [28,29].

CSCL has been widely used in LL and researchers have used collaboration for developing all main language learning skills such as reading [30], listening, speaking [31] and writing [32,33]. Also, the possibilities of collaboration have been explored in other fundamental aspects of LL such as pronunciation [34- 37] and grammar [38]. Finally, another popular use of CSCLL is telecollaboration where learners from different countries collaborate in PBL activities to increase the use of target language [39].

Many researchers have concluded that the appropriate orchestration and planning conducted by the teachers play an important role in the language learning outcome [40,41]. Also, the relationship between technology, pedagogy and learners’ needs must be analysed in a holistic and more systematic way [42]. Consequently, further research is needed on how teachers orchestrate learning through textual and non-textual modalities, as well as on when and how this orchestration is conducted and what effects it has on LL [43,44].

Orchestration in CSCL

One of the main problems that educators must overcome when implementing learning scenarios to real life is the many unpredictable factors that can influence or even destroy the desired outcomes. One way to address this problem is to create flexible learning designs that can be adapted on-the-fly so that teachers can implement the scenarios despite the occurring problems [3]. Trying to address these problems, many researchers use the term “orchestration” to describe the real-time management of the various learning processes.

Orchestration is not new to learning studies since it was first introduced by Brophy & Good [45] and was also used by Trouche [46], who applied the metaphor of instrumental orchestration into mathematics. However, it was the work of Dillenbourg and Jermann [14] which brought orchestration into the spotlight. According to Dillenbourg’s most cited definition “orchestration refers to how a teacher manages, in real time, multi-layered activities in a multiconstraints context” [47]. Apart from Dillenbourg’s definition we encounter a few more in the literature such as Chan’s [48] narrower version, Prieto et al.’s [49] more comprehensive and Tchounikine’s [51] proposal to distinguish the terms orchestration technology (OT) and orchestrable technology (OA).

There is little consensus among Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) community members regarding what orchestration is, how it should be addressed and what factors should include. Nonetheless, there are eight key elements which are widely accepted, according to Prieto et al. [50]:

• Pragmatism and constraints in classrooms.

• Empowerment, control and management of different learning activities.

• Visibility, awareness and monitoring of the activities.

• Flexibility and adaptation of the original lesson plans to deal with unexpected events.

• Minimalism in classroom technologies.

• Teacher centrism and sharing the orchestration load.

• Designing for preparation, appropriation, and enactment of the learning scenarios.

• Multilevel integration and synergy by combining different and multiple elements.

The same author introduced a framework that depicts the current discourse on classroom orchestration. This framework, called “5+3”, is a conceptual tool that divides the eight main elements, into three categories: activities that orchestration entails, actors that perform these activities and background that shapes how orchestration is performed [20] as shown in Figure 1.

The wide diversity in the field of CSCL regarding orchestration tools and their uses is highlighted by the following two literature reviews. Van Leeuwen & Rummel’s review [18] regarding orchestration tools included 26 studies, mostly mirroring tools (giving data without further interpretation) which provide either cognitive or social analytics. This study concludes that it is essential for teachers to support students’ collaboration at both the cognitive and social levels through orchestration tools, and it highlights the significant diversity in the types and functions of these tools as well as the variety of information they display. The second study by Song [17] reviewed 43 studies published during 2010-2019 all using orchestration with technology to assist pedagogical practices. This study adopts Tchounikine’s classification [51] and divides the tools into (i) orchestration technology (OT) and (ii) orchestrable technology (OA). In brief, Song concludes that there is no holistic picture of the research regarding orchestration. The study indicates that there is a need for new tools and methods which should be designed by taking instructional design into account. By doing so, these tools and methods will be more teacher friendly and could be applied in a wider community. A compromise between OA and OT may be the ideal strategy to help teachers work as facilitators in the orchestration process.

An extensive review in the field of CSCL is beyond the scope of this study but it is already evident that there are many different orchestration strategies developed and used in different disciplines and learning environments [17,18]. Nevertheless, there is a need for more rigorous work in the field since many open questions still exist.

The role of students’ motivation, engagement, and selfregulation

As already mentioned, one of the key factors in students’ performance is motivation. Researchers claim that students’ performance is enhanced when motivation is translated into behavioural, emotional, and cognitive engagement [52,53]. Behavioural engagement involves the active participation in learning activities, emotional engagement means that students must be interested and in a good mood when dealing with the activities, and cognitive engagement means that students actively use some strategies to understand information and solve problems [52]. Along with motivation and engagement, self-regulation is one of the primary factors that influence students’ learning outcomes. Self-regulation is the process by which learners personally activate and sustain cognitions, affects, and behaviors that are systematically oriented toward the attainment of their goals [54]. It is a vital part of the learning process and an indicator of the students’ future academic achievements [55,56].

Review Methodology

A literature review has been carried out with the aim of developing an accurate image of the papers that are relevant to orchestration of CSCLL activities. The period covered in this search was 2000 to 2023 Q1.

In order to find relevant literature sources, we used online research databases that host articles relevant to education and technology, such as Elsevier Science Direct, ACM Digital Library, Springerlink, ISI Web of Science, IEEExplore, ProQuest, Taylor & Francis and EdITLib. Since the main research question is to identify the orchestration techniques being used in collaborative language learning environments the following search terms were selected: (“language learning” OR “language acquisition” OR “EFL”) AND (“collaborative learning” OR “CSCL” OR “CSCLL”) AND (“orchestration” OR “orchestrating technology” OR “scaffolding” OR “classroom management”). The terms “motivation”, “engagement”, and “self-regulation” from RQ2 are very specific and were therefore not included in the initial search query. However, these aspects were thoroughly examined in subsequent stages of the study. Finally, the snowballing technique was employed.

Through the search terms above we obtained 68 articles. Another six studies were selected by thread searches of reference lists. From these we selected studies that were empirical (using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methodology) and published in academic journals and books. Doctoral dissertations, conference proceedings, and unpublished reports were excluded from this review to ensure the inclusion of high-quality, peer-reviewed sources that offer consistent, reliable, and accessible evidence for robust analysis. This research strategy produced 30 results.

Results

An overview of the literature is presented below. The analysis and coding of the selected papers has been done by using the revised 5+3 framework [20] as a general guideline, which resulted in the following categories, shown in Figure 2.

General Information

The selected articles come from 18 journals and two books relevant to the use of technology in education. The journals with the greater number of articles in the study are Language Learning & Technology (4), Educational Technology & Society (4), International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (4), CALICO Journal (2) and Interactive Learning Environments (2).

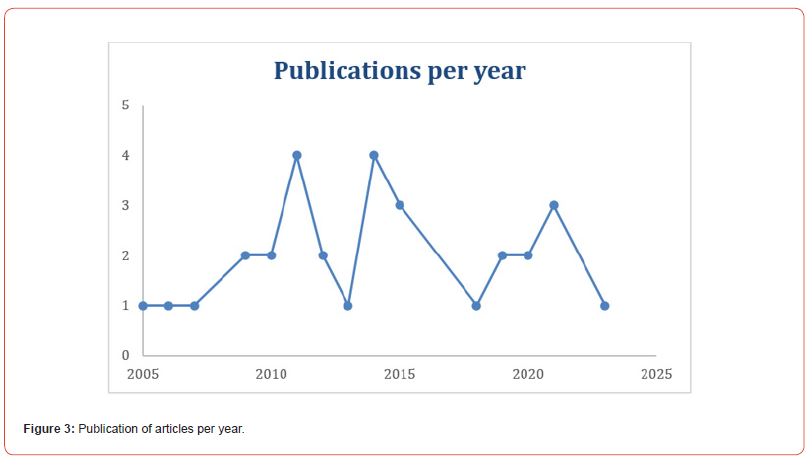

Regarding the publication date of the articles, as shown in Figure 3, after 2010 there is a stable production of two to four studies per year. From the included studies 14 use a qualitative methodology and the remaining 16 follow a mixed methodology, combining both qualitative and quantitative data.

Activities

Regarding the language skills that the studies have explored, the most popular one is writing which appears in 11 studies. Other popular skills are vocabulary and grammar, as well as reading appearing in six papers. Listening, pronunciation and spelling are also on the list of practiced skills. Finally, four studies explore the language as a whole and suggest that they are not focusing only on one specific skill, but they work on language communication as a unity (Figure 4).

The duration of the studies varies from just one session to two years. 17 out of the 30 studies lasted from one month to one semester, five lasted approximately two weeks and six only one to three sessions. On the other hand, one study was continued for two academic years.

The tools used for the orchestration were mostly for mirroring and facilitating orchestration during the lesson. More details regarding orchestration tools are discussed below.

Actors

The sample size also varies. Some qualitative case studies, which primarily analyze collaborative interactions among participants, involve a small group of students (ranging from four to nine). In contrast, other studies include larger groups, with participant numbers varying from 20 to 83, and an average of about 35 learners. The number of teachers included in the studies is one in 15 studies, while in five studies there are two to five teachers and in the remaining 10 there is no reference to the number of educators participating. These results comply with other reviews for orchestration tools noting that the number of participants is usually small [18].

The tools used during the studies for orchestrating learning are almost equally divided in the categories of OA and OT as introduced by Tchounikine [51] and used by Song [17]. 17 studies are in the OA category and incorporate tools that are created for general use such as Learning Management System (LMS), wikis, chats, and other educational software, while the other 13 use technology particularly developed for orchestration.

Finally, regarding social level of collaboration, students work in small groups of three to five people in 25 studies and in large groups of 25 people only in one. There are also two studies with students working in pairs and two more where grouping is not specified.

Background

The students that take part in 15 studies are university students – either undergraduates or postgraduates – and in another 14 studies they attend K-12 – either primary or secondary school. There is also one study in a private language school.

Of the 30 reviewed studies, 16 studies were conducted in Asia, with 6 studies conducted in Taiwan, 4 in Singapore, 2 in Hong Kong, 1 in Malaysia, 1 in Indonesia, 1 in Beijing and 1 in Korea. There are also 7 studies from Europe, 3 from the USA, 2 from Chile, 1 from Brazil, 1 from Australia. This geographical distribution, as shown in Figure 5, depicts the fact that the large amount of research in the field of LL originates from the Eastern countries, in contrast with the studies exploring orchestration in other fields, such as science and maths, that mostly come from western countries [17].

The learning environment is face-to-face in 15 studies, online for six and blended for the remaining nine. All the studies that are held face-to-face concern students in K-12 and only one is about university students. Blended learning environments are used almost exclusively in universities, with only one blended learning study in K-12 setting. Finally, all the online studies refer to university students.

The target language is English as a second or foreign language in 19 studies, Chinese in four, Spanish in two, Swedish in one, French in one, and German in one.

The main problems or constraints that appear in these studies are the available time and teachers’ ability and/or willingness to use the interventions. Also, some studies refer to curriculum limitations and limited resources, while others refer to the limited analytical features their tools offer.

RQ1 results: Different types of orchestration applied to CSCLL

During our literature review we categorized the orchestration tools and techniques by means of Tchounikine’s [51] classification into OT and OA. The first category includes tools that are designed for teachers specially to facilitate orchestrating classroom tasks and targeting to reduce the teacher’s orchestration load. In our study we encountered eleven tools that could be enlisted in this category, including the specially designed VLE called WebCT [38], the CMC tool AMANDA [57], the CAREER system [30], the process-writing wizard [58], the MCER system [59], the collaborative language laboratory [60], the configurable conversational agent MentorChat [61], the collaborative language learning through avatar system CELLA [62], the collaborative learning platform with TOEIC questions [63] and the rapid CSCL tool GroupScribbles [7,64,65]. The tools in this category present a large diversity regarding their function and the type of information they offer. This finding aligns with other studies in the field and justifies the need for more systematic and coherent research that builds upon each other’s work [18].

The second category includes generic learning tools that teachers can adapt or configure for different purposes before or during the class so that they can orchestrate the learning procedure. Our literature review included 16 orchestration strategies in this category with the most popular being the use of generic LMSs as appearing in five studies [19,66-69]. Another tool that is used in four studies to facilitate collaborative writing activities is wikis such as Pbwiki, Pbworks, wikispaces and wiki tools integrated into LMSs [70-73]. For the sake of collaborative writing two other studies made use of Google Docs, even though the data collected regarding students’ engagement is limited [66,74]. Usually, such collaborative writing tools are paired with chats to enable students’ communication and allow them to plan and complete their tasks. Finally, other studies incorporate tools such as IWBs [75], single display groupware with multiple mice [76], video editors and other already existing technology [77,78] or even instructional conversations around computers [79] and known orchestration frameworks [80].

We also used vanLeeuwen and Rummel’s [18] classification to categories the use of tools in three main categories as explained previously: mirroring, alerting, and guiding. Regarding this categorization only four tools can offer something more elaborate than mirroring. Two tools include some alerting features when students mispronounce newly taught vocabulary [30,60] and another two studies include guiding features where teachers could get some data after the completion of the tasks and analyse them to provide appropriate feedback to students [41,62]. These findings are in line with other studies in the field of orchestration where it is mentioned that most of the tools offer just mirroring function and further interpretation, and action is left to the teacher [18].

Regarding the implementation stage of these orchestration tools, most are designed to support orchestration either before or during the learning process. However, only three provide data as feedback to aid in re-orchestrating subsequent enactments of the learning scenario [7,37,65].

RQ2 results: Effects on students’ motivation, engagement, and self-regulation

Our review showed that students’ performance can be enhanced when motivation, engagement, and self-regulation are high during the learning process. 20 out of 30 studies make reference to one or more of these factors.

Motivation is by far the most popular aspect of students’ performance in literature since it appears in seven studies. Some studies report that the use of CSCL in LL scenarios improved both motivation and performance of students because of the increased exposure and interaction in the target language [38,41,58,61,67,77], while others claim that even though there was an improvement in motivation this has little influence on the learning outcome [63]. Particularly, Kuo et al. [63] suggests that to improve the learning outcome a learning style-based approach needs to be followed. In addition, some researchers pointed out the importance of choosing interesting topics when it comes to online discussions along with the importance of preventing inactive group members [57].

Engagement is another factor of learners’ performance. Wang [71] mentions that wikis helped increase students’ cognitive engagement, while Kuo et al. [63] state that high level students presented higher cognitive engagement and had less irrelevant responses during their chat conversations. Also, other researchers claim that the use of orchestrated CSCLL activities caused higher engagement, equal participation, and better concentration [19,37,62,70,76-78,80].

Finally, regarding self-regulation, many studies claim that CSCLL positively affects students’ interdependence and consequently learners take more seriously their participation in the collaborative activities [30,37,57,70,72].

RQ3 results: Effects on learning outcome

From the selected studies, there are conclusions related to students’ learning outcome in 18 of them and most of the findings are encouraging. Students that engage in collaborative activities facilitated by orchestration tools or activities present positive learning attitudes

Particularly, in writing tasks the results include better writing products with improved content and organization [58,74,77]. Some studies, however, claim that the language awareness was improved but the cohesion was problematic [66], while others mention that there are no statistically significant differences in terms of fluency, accuracy, and complexity [70] or that the outcome varies due to learners’ proficiency [37].

When it comes to grammar and vocabulary learning the results are more evidently positive. All the relevant studies report better learning outcomes and significant knowledge gain. Students can better cope with troublesome knowledge and improve their vocabulary retention and pronunciation [32,38,60,63,76,80].

Moreover, the studies that examined reading and communication as an entity present positive result. Specifically, orchestrated collaborative activities seem to facilitate the acquisition of reading skills and enhance participation among students [19,30,72,78]. Regarding communication, the results indicate both an improvement in the quality and quantity of conversations, as well as a higher level of explicit reasoning and productive dialogue [62].

Discussion

Summary of evidence for RQ1: To what extent have orchestration strategies been applied to CSCLL?

According to our results, although there are few studies regarding the implementation of orchestration strategies to CSCLL, it appears that orchestration in CSCL environments could be a promising solution to certain implementation challenges. Ernest et al. [81] refers not only to the importance of the awareness of multilayered elements involved in collaborative online LL but also to the role of the teacher(s) ‘orchestrating’ the activity. Moreover, Calderón et al. [60] mention in their work that learning design should take into consideration not only the students but also the teachers whose role is defined by orchestration. Wen et al. [82] concludes that since not all the students seem to benefit from CSCLL activities, it is possible that the teacher as the lesson orchestrator should pay more attention to pedagogical design and classroom management control, in which stronger and specific scaffolding and guidance should be offered. More recently, Wen and Song [65] emphasize the need to align LD with orchestration and LA to achieve the desirable learning outcomes.

Summary of evidence for RQ2: Can the orchestration of CSCLL activities have an impact on students’ motivation, engagement, and self-regulation?

The results of our study are largely positive, with 64% of the included papers examining the factors in question and all reporting improvements in both students’ motivation and engagement. However, it is important to note that the data collected in these studies were derived from typical LMS and tools, rather than being specifically selected for language learning (LL) contexts. As Thomas et al. [83] highlight, the process of second language acquisition (SLA) is complex, so further research is needed to identify which indicators offer meaningful insights for LL environments.

Summary of evidence for RQ3: Can the combination of orchestration strategies and CSCLL have a significant impact on learning outcome?

Despite the limited studies regarding orchestration and CSCLL, the use of collaborative activities in LL appears to have a positive impact on the learning outcome. At the same time orchestration seems beneficial when used in collaborative learning scenarios. Consequently, the idea of combining these features is likely to have a significant impact on language learners’ performance. Further study is required in the field to prove this hypothesis and reveal if the results – either positive or negative – are due to orchestration technology, or the use of learning technology in general.

Concluding thoughts

The study of the recent literature revealed that there are many different strategies used to support orchestration in CSCL, while there are many examples of different collaborative scenarios used successfully in LL. Existing literature offers supporting evidence that the use of CSCL in LL has positive impact on both the learning outcome and students’ motivation factors, yet appropriate orchestration is essential for the successful enactment of CSCL activities. However, unlike other knowledge domains, LL has not yet embraced the notion of orchestration and more research is necessary to understand how the complex process of SLA can be facilitated by orchestration.

Consequently, a prominent challenge in this field is how to measure the impact of orchestration on CSCLL and which are the specific indicators to be analysed so that meaningful knowledge of the LL process can be provided. Moreover, the role of theory guiding CALL researchers is important [83].

Recently, it has become more evident that in order to have successful enactment of collaborative learning activities, it is essential to align LD pedagogically grounded, orchestration and LA. More research should be done towards this direction and researchers should try to build on each other’s work more explicitly [16].

Finally, we must address the limitations of the present study. First, since the term “orchestration” is relatively recent, similar concepts may be covered in other CSCLL literature without explicitly using this term. Although the authors carefully reviewed the CSCLL literature for relevant aspects, some relevant studies may have been overlooked. Another significant limitation is that many studies included in our review have small sample sizes or limited durations, which may impact the validity of their results. Additionally, we excluded conference papers, which often present preliminary research. This exclusion may have restricted our findings and led to some omissions in our results [84,85].

Conclusion and challenges for future research

The results of the present study suggest that the level of CSCL implementation in a LL environment is surprisingly low, even though the literature review has shown that there are many benefits when using CSCLL approaches. It is suggested that orchestration is critical for the successful implementation of CSCLL activities in real classrooms and that an alignment of LD, orchestration and LA may provide a promising solution to the low implementation of technology in language education. However, the available research is mostly of exploratory nature, with small sample sizes and there is a need for more rigorous work that would offer firmer conclusions regarding how the orchestration of CSCLL activities can influence the learning outcome and students’ attitude.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bush MD, Terry RM (1997) Technology-Enhanced Language Learning. National Textbook Company.

- Levy M (1997) Computer-Assisted Language Learning: Context and Conceptualization. Oxford University Press.

- Dimitriadis Y, Goodyear P (2013) In medias res: reframing design for learning. Research in Learning Technology pp. 21.

- Luckin R (2008) The learner centric ecology of resources: A framework for using technology to scaffold learning. Computers and Education 50(2): 449-462.

- Malliarakis C, Satratzemi M, Xinogalos S (2014) Research on e-Learning and ICT in Education.

- Firth A, Wagner J (1997) On Discourse, Communication, and (Some) Fundamental Concepts in SLA Research. The Modern Language Journal 81(3): 285-300.

- Wen Y, Looi CK, Chen W (2012) Supporting teachers in designing CSCL activities: A case study of principle based pedagogical patterns in networked second language classrooms. Educational Technology and Society 15(2): 138-153.

- Begum R, Naga Dhana Lakshmi R (2023) ICT-Based Collaborative Learning Approach: Enhancing Students’ Language Skills pp. 11-18.

- Hmelo-Silver CE, Jeong H (2021) Benefits and Challenges of Interdisciplinarity in CSCL Research: A View from the Literature. Frontiers in Psychology 11.

- Balacheff N, Ludvigsen S, Jong TDe (2009) Technology-Enhanced Learning. In Vasa.

- Daradoumis T, Kordaki M (2011) Employing Collaborative Learning Strategies and Tools for Engaging University Students in Collaborative Study and Writing. In Techniques for Fostering Collaboration in Online Learning Communities: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives pp. 183-205.

- Jeong H, Hmelo-Silver CE, Yu Y (2014) An examination of CSCL methodological practices and the influence of theoretical frameworks 2005-2009. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 9(3): 305-334.

- Stahl G, Koschmann T, Suthers D (2006) Computer-supported collaborative learning: An historical perspective. In RK Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, UK pp. 409-426.

- Dillenbourg P, Jermann P (2010) Technology for classroom orchestration. New Science of Learning: Cognition, Computers and Collaboration in Education pp. 525-552.

- Dillenbourg P, Prieto LP, Olsen JK (2018) Classroom Orchestration. In F Fischer, CE Hmelo-Silver, SR Goldman, P Reimann (Eds.), International Handbook of the Learning Sciences (1st ed.). Routledge pp. 180-190.

- Rodríguez-Triana MJ, Prieto LP, Dimitriadis Y, de Jong T, Gillet D (2021) ADA for IBL: Lessons learned in aligning learning design and analytics for inquiry-based learning orchestration. Journal of Learning Analytics 8(2): 22-50.

- Song Y (2021) A review of how class orchestration with technology has been conducted for pedagogical practices. Educational Technology Research and Development 69(3): 1477-1503.

- van Leeuwen A, Rummel N (2019) Orchestration tools to support the teacher during student collaboration: a review. In Unterrichtswissenschaft. Springer VS 47(2): 143-158.

- Xu Q, Sun D, Zhan Y (2023) Embedding teacher scaffolding in a mobile technology supported collaborative learning environment in English reading class: students’ learning outcomes, engagement, and attitudes. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organization 17(1-2): 280-302.

- Prieto LP, Dimitriadis Y, Asensio-Pérez JI, Looi CK (2015) Orchestration in Learning Technology Research: Evaluation of a conceptual framework. Research in Learning Technology 23(1063519): 1-15.

- Stahl G, Spada H, Miyake N, Law N (2011) Introduction to the Proceedings of CSCL 2011 The CSCL Community and Conference.

- Kukulska-Hulme A, Viberg O (2018) Mobile collaborative language learning: State of the art. British Journal of Educational Technology 49(2): 207-218.

- Dillenbourg P (1999) What do you mean by “collaborative learning”? In Collaborative learning Cognitive and computational approaches 1(6): 1-15.

- Hernández-Leo D, Asensio-Pérez JI, Dimitriadis Y, Villasclaras ED (2019) Generating CSCL Scripts: From a Conceptual Model of Pattern Languages to the Design of Real Scripts. P Goodyear, S Retalis (Eds.), Technology-Enhanced Learning, Design patterns and pattern languages. Sense Publishers pp. 49-64.

- Cullen R, Kullman J, Wild C (2013) Online collaborative learning on an ESL teacher education programme. ELT Journal 7(4): 425-434.

- Domalewska D (2014) Technology-supported classroom for collaborative learning: Blogging in the foreign language classroom. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology 10(4): 21-30.

- Dooly M (2008) Understanding the many steps for effective collaborative language projects. Language Learning Journal 36(1): 65-78.

- Oxford RL (1997) Collaborative Cooperative Learning, and Interaction: Three Learning, Communicative Strands in the Language Classroom. The Modern Language Journal 81(4): 443-456.

- Wen Y, Chen W, Looi C (2010) “Ideas First” in Collaborative Second Language (L2) Writing: An Exploratory Study. Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference of the Learning Sciences 1: 436-443.

- Lan YJ, Sung YT, Chang KE (2009) Let us read together: Development and evaluation of a computer-assisted reciprocal early English reading system. Computers and Education 53(4): 1188-1198.

- Wang YC (2020) Promoting English Listening and Speaking Ability by Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 313: 228-233.

- Lin SM, Griffith P (2014) Impacts of Online Technology Use in Second Language Writing: A Review of the Literature. Reading Improvement 51(3): 303-312.

- Strobl C (2014) Affordances of web 2.0 technologies for collaborative advanced writing in a foreign language. CALICO Journal 31(1): 1-18.

- Chen W, Looi CK, Wen Y (2011) A scaffolded software tool for L2 vocabulary learning: Group Scribbles with graphic organizers. CSCL 2011 Conference Proceedings - Long Papers, 9th International Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Conference 1: 414-421.

- Hung HC, Young SSC, Lin CP (2015) No student left behind: a collaborative and competitive game-based learning environment to reduce the achievement gap of EFL students in Taiwan. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 24(1): 35-49.

- Lin CC, Chan HJ, Hsiao HS (2011) EFL Students’ Perceptions of Learning Vocabulary in a Computer-Supported Collaborative Environment. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology - TOJET 10(2): 91-99.

- Wen Y, Looi CK, Chen W (2015) Appropriation of a representational tool in a second-language classroom. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 10(1): 77-108.

- Orsini-Jones M, Jones D (2007) Supporting Collaborative Grammar Learning via a Virtual Learning Environment. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 6(1): 90-106.

- Dooly M (2015) It takes research to build a community: Ongoing challenges for scholars in digitally- supported communicative language teaching. Calico 32(1): 172-194.

- Del M, Foro IV, Estudios NDE, Lenguas EN (2008) Teachers’ beliefs and the orchestration of classroom interaction. Memorias Del IV Foro Nacional de Estudios En Lenguas pp. 121-132.

- Meskill C (2005) Triadic Scaffolds: Tools for Teaching English Language Learners with Computers. Language Learning & Teachnology 9(1): 46-59.

- Sun SYH (2017) Design for CALL-possible synergies between CALL and design for learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning 30(6): 575-599.

- Hakami L, Hernández‐Leo D, Amarasinghe I, Sayis B (2024) Investigating teacher orchestration load in scripted CSCL: A multimodal data analysis perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology 55(5): 1926-1949.

- Harklau L (2002) The role of writing in classroom second language acquisition. Journal of Second Language Writing 11(4): 329-350.

- Brophy J, Good TL (1986) Teacher behavior and student achievement. In MC Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Teaching (3rd ed). Macmillan pp. 376-391.

- Trouche L (2004) Managing the complexity of human/machine interactions in computerized learning environments: guiding students.

- Dillenbourg P (2013) Design for classroom orchestration. Computers and Education 69: 485-492.

- Chan TW (2013) Sharing sentiment and wearing a pair of ‘field spectacles’ to view classroom orchestration. Computers & Education 69: 514-516.

- Prieto LP, Holenko Dlab M, Gutiérrez I, Abdulwahed M, Balid W (2011) Orchestrating technology enhanced learning: a literature review and a conceptual framework. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning 3(6): 583-598.

- Prieto LP, Wen Y, Caballero D, Dillenbourg P (2014) Review of Augmented Paper Systems in Education: An Orchestration Perspective. Educational Technology & Society 17(4): 169-185.

- Tchounikine P (2013) Clarifying design for orchestration: Orchestration and orchestrable technology, scripting and conducting. Computers and Education 69: 500-503.

- Fredricks J, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research 74(1): 59-109.

- Reeve J (2013) How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology 105(3): 579-595.

- Zimmerman BJ (2000) Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M Boekaerts, PR Pintrich, M Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press pp. 13-39.

- Harris KR, Graham S, Mason LH, Saddler B (2002) Developing Self-Regulated Writers. Theory Into Practice 41(2): 110.

- Jarvela S, Jarvenoja H (2011) Socially Constructed Self-Regulated Learning and Motivation Regulation in Collaborative Learning Groups. Teachers College Record 113(2): 350-374.

- Irala EA, Torres PL (2009) The Use of the CMC Tool Amanda for the Teaching of English. In E-Collaboration: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications 1: 307-321.

- Yeh SW, Lo JJ, Huang JJ (2011) Scaffolding collaborative technical writing with procedural facilitation and synchronous discussion. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 6(3): 397-419.

- Lan YJ, Sung YT, Chang KE (2013) From Particular to Popular: Facilitating EFL Mobile-Supported Cooperative Reading. Language Learning & Technology 17(3): 23-38.

- Calderón JF, Nussbaum M, Carmach I, Díaz JJ, Villalta M (2016) A single-display groupware collaborative language aboratory. Interactive Learning Environments 24(4): 758-783.

- Tegos S, Demetriadis S, Tsiatsos T (2014) A Configurable Conversational Agent to Trigger Students’ Productive Dialogue: A Pilot Study in the CALL Domain. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 24(1): 62-91.

- Kim SH (2015) Communicative Language Learning and Curriculum Development in the Digital Environment. Asian Social Science 11(12): 337-352.

- Kuo YC, Chu HC, Huang CH (2015) A learning style-based grouping collaborative learning approach to improve EFL students’ performance in English courses. Educational Technology and Society 18(2): 284-298.

- Wen Y (2019) Teacher Orchestration in the Networked Classroom. In Computer-Supported Collaborative Chinese Second Language Learning: Beyond Brainstorming. Springer Singapore pp. 141-157.

- Wen Y, Song Y (2021) Learning analytics for collaborative language learning in Classrooms: From the holistic perspective of learning analytics, learning design and teacher inquiry. Technology & Society 24(1): 1-15.

- Blin F, Appel C (2011) Computer supported collaborative writing in practice: An activity theoretical study. CALICO Journal 28(2): 473-497.

- Gabarre C, Gabarre S (2010) Raising exposure and interactions in French through computer - Supported collaborative learning. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities 18(1): 33-44.

- Nissen E, Mangenot F (2006) Collective Activity and Tutor Involvement Language Teachers and Learners. CALICO Journal 23(3): 601-622.

- Wang Y, Chen NS (2012) The collaborative language learning attributes of cyber face-to-face interaction: The perspectives of the learner. Interactive Learning Environments 20(4): 311-330.

- Elola I, Oskoz A, County B, Guerrero D (2010) Collaborative Writing: Fostering Foreign Language and Writing Conventions Development. Language Learning & Technology 14(3): 51-71.

- Wang YC (2014): Using wikis to facilitate interaction and collaboration among EFL learners: A social constructivist approach to language teaching. System 42(1): 383-390.

- Su Y, Li Y, Hu H, Rosé CP (2018) Exploring college English language learners’ self and social regulation of learning during wiki-supported collaborative reading activities. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 13(1): 35-60.

- Woo M, Chu S, Ho A, Li X (2011) Using a wiki to scaffold primary-school students’ collaborative writing. Educational Technology and Society 14(1): 43-54.

- Abrams ZI (2019) Collaborative writing and text quality in Google Docs. Language Learning and Technology 23(2): 22-42.

- Lin CC, Hsiao HS, Tseng SP, Chan HJ (2014) Learning English vocabulary collaboratively in a technology-supported classroom. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology 13(1): 162-173.

- Szewkis E, Nussbaum M, Rosen T, Abalos J, Denardin F, et al. (2011) Collaboration within large groups in the classroom. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 6(4): 561-575.

- Azis YA, Husnawadi H (2020) Collaborative digital storytelling-based task for EFL writing instruction: Outcomes and perceptions. Journal of Asia TEFL 17(2): 562-579.

- Hell A, Godhe AL, Wennås Brante E (2021) Young L2-learners’ meaning-making in engaging in computer-assisted language learning. The EuroCALL Review 29(1): 2.

- Ibanez M, Delgado Kloos C, Leony D, Garcia Rueda JJ, Maroto D (2011) Learning a Foreign Language in a Mixed-Reality Environment. IEEE Internet Computing 15(6): 44-47.

- Ioannou M, Ioannou A, Georgiou Y, Retalis S (2020) Designing and Orchestrating the Classroom Experience for Technology-Enhanced Embodied Learning. In M Gresalfi, SI Horn (Eds.), The Interdisciplinarity of the Learning Sciences, 14th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS). International Society of the Learning Sciences 2: 1079-1086.

- Ernest P, Heiser S, Murphy L (2011) Developing teacher skills to support collaborative online language learning. pp. 37-41.

- Wen Y, Looi CK, Chen W (2009) Who are the Beneficiaries When CSCL Enters into Second Language Classroom. Global Chinese Conference on Computers in Education (GCCCE 2009).

- Thomas M, Reinders H, Gelan A (2017) Learning Analytics in Online Language Learning: Challenges and Future Directions.

- Dimitriadis Y, Prieto LP, Asensio-Pérez JI (2013) The role of design and enactment patterns in orchestration: Helping to integrate technology in blended classroom ecosystems. Computers and Education 69: 496-499.

- Yan H, Lin J (2019) Integrating Web-based Collaborative Learning into the Pronunciation Curriculum. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series pp. 83-87.

-

Eirini Dellatola*, Thanassis Daradoumis and Yiannis Dimitriadis. An Orchestration Perspective on Computer-Supported Collaborative Language Learning: A literature Review. Iris J of Edu & Res. 4(2): 2024. IJER.MS.ID.000581.

-

Collaborative Language Learning, Computer-Assisted Language Learning, Orchestration

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.