Research Article

Research Article

Using Repeated Viewings of Television Cartoons to Enhance Dialogic Exchanges Between a Parent and Preschool Children

Laveria F Hutchison*

Associate Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, University of Houston, USA

Laveria F Hutchison, Associate Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, University of Houston, USA

Received Date:February 19, 2024; Published Date:March 19, 2024

Abstract

Young children between the ages of two-years old and five-years old watch approximately eighteen hours of television each week. This frequent viewing of television is often without any type of cognitive interaction with a person, especially an adult. This article is based on the observations of a parent’s use of dialogic exchanges with her two young daughters during the repeated viewing of episodes from a televised cartoon series. Post-test data sets from the CogAT Kindergarten Test: Cognitive Abilities Test show an increase in the scores in each category. The structure of using repeated viewing of television cartoons with young children provides a process for parents, educators, and caregivers to use to enhance learning and oral language development during dialogic exchanges. The dialogic exchanges are framed around questions and statements used before, during, and following the repeated viewing of the cartoon episodes.

Keywords:Dialogic exchange; Oral language; Repeated viewing; Cartoons; Cognitive development

Introduction

Prior to traditional reading instruction starting in school settings, young children can develop a variety of pre-reading skills that include oral language development, comprehension skills, and interest in learning [1]. Research has shown that early oral language capacity can be a positive factor for later literacy achievement and for general academic advancements [2]. Therefore, to reduce reading challenges among school-aged children, oral language development has received attention in research [3,4].

A frequently used activity for oral language development is the adult and child shared narrative reading of a favorite book. The reading of a favorite book is often requested by the young child to be re-read numerous times for continued enjoyment. This literacy activity can be structured to provide a dialogic discussion about a book the adult is reading to the child. This type of shared activity between an adult and a child can create a setting that promotes the development of critical thinking and dialogic exchanges that can lead to oral language development, vocabulary development and other literacy skills [5,6]. This setting establishes dialogical exchanges between the adult and child that allows the child to express interesting thoughts without being criticized by the adult, and a process for using previously learned information already gained by the young child [5].

Research has provided evidence indicating children request numerous repeated readings of their favorite books [7,8]. According to Klinkenborg [9], “childhood is an oasis of repetitive acts” (p. A18) and in this case, repeated reading of a favorite book. Samuels [10] introduced the concept of repeated oral reading for use in classroom settings, and Levy et al., 1993, reported that repeated oral readings for young children increased their literacy skills. Korat et al., 2017, Monobe, Bintz, and McTeer [11], and Therrien [12] identified the positive effectiveness of repeated readings teachers found among elementary students. Considering the research-based effectiveness of repeated reading of text sources in educational settings, the author studied the use of guided repeated viewing of cartoons between an adult and two young children using dialogic exchanges following the repeated viewing of a cartoon episode.

According to Morowatsharifabad, Karimi, and Ghorbanzadeh [13], children who are two to five years old watch approximately eighteen hours of television each week. Most homes in the United States have at least two television sets [14-16]. Considering the availability of this media device in homes in this country, meaningful oral interactions between an adult and children using television viewing could unfold as an effective cognitive experience [17]. It would be helpful if parents, educators, and caretakers could be provided with interesting ways to use television viewing, especially cartoon viewing, to assist with promoting oral language and cognitive development.

In 2005, Zimmerman and Christakes published the results of a longitudinal study that analyzed the effects of television viewing among children who were three to five years old. This study provided evidence showing children in this age group who watched television on an average of 2.2 hours per day experienced negative results on the Peabody Individual Achievement Test’s subtest for Reading Recognition. However, Moses [18] conducted a metaanalysis of television viewing patterns among young children and found that moderate amounts of television viewing can enhance reading skills. Strouse [19] at Peabody College found that dialogic exchanges with parents during television viewing assisted in their children’s capacity to score higher on post-assessments of vocabulary comprehension than children not encountering adult verbal interactions during television viewing. And Hart and Risley [20] found that a child’s vocabulary development is based on experience. Considering these differential results, further research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of television viewing among young children. As a result, this study investigated a threetimes repeated viewing of a television cartoon episode by two young children and their mother over a period of six weeks.

The Present Study

The central idea for this article was framed in the sociocultural theoretical perspective that acknowledges the contributions social connections and dialogic exchanges make in assisting young children in receiving information and in learning new concepts from repeated exposures to a cartoon episode. A sociocultural perspective contends that parents, other adults, and culture can assist in the development of higher order thinking functions and in this article, among two young children [21]. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship observed by the author/researcher between a parent’s implementation of dialogic exchanges used during three repeated viewings of two different cartoon episodes with her two young children. Narrative responses and comprehension understanding of the development of ideas from the repeated viewing of the cartoon episodes were observed by the author/researcher. This article provides ideas for using guided repeated viewings of cartoons, with dialogic exchanges between an adult and two young children, to promote oral language development, comprehension skills, and basic learning. Using the same television cartoon episode that was repeated three times, segment samples were used to pose questions and statements for dialogic exchanges between the mother and the two young children. A pre-test and post-test were used along with an analysis of language samples (unique words and phrases) from the young children captured from the dialogic discussion exchanges with their mother.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were two pre-school female children, ages four-years old and three-years old, and their mother, a certified elementary teacher who also has a master’s degree. The mother self-identified herself and her children as English-speaking. The mother and her two children, in their home, watched two different cartoon episodes three times each week for thirty-minutes over a six-week period. The other participant in this study was the author/ researcher who observed the mother and her children viewing the cartoon and participating in dialogical exchanges. The author/ researcher administered the pre-test and the post-test to the two children and conducted two semi-structured interviews and a member check interview with the mother to review for content accuracy of the content captured from the interviews.

Monty (all names are pseudonyms), a four-year-old, sat next to her three-year old sister, Margie, on their special rug waiting for their mother, Elizabeth, to start a repeated recording of an episode of their favorite cartoon, PAW Patrol. This is a children’s cartoon episode that focuses on a character named Ryder who leads a group of search and rescue dogs known as the Paw Patrol to protect the Adventure Bay community. Elizabeth pre-recorded two cartoon episodes before their first viewing so that she could purposefully guide repeated viewings of the cartoon episodes with Monty and Margie. Elizabeth used the same episode for three weeks before starting the second episode for her young children to watch again for three weeks. Like many parents, Elizabeth accepts that her daughters enjoy watching cartoons. However, Elizabeth also realizes that just watching a cartoon once, without some type of purposeful viewing guidance or dialogic parent-child exchanges, does not always promote learning, enjoyment and engagement, the understanding of events, oral language development, cognitive connections for learning new concepts, or the capacity to make connections to previously learned information. Therefore, Elizabeth allows, and often encourages, her daughters to watch their favorite cartoons repeatedly – but with guidance and with dialogic exchanges.

Setting the Context for the Observation

This article provides ideas for using guided repeated viewings of cartoons that also includes dialogic exchanges between an adult and children to promote learning. Additionally, this article reports on an observation of a parent using repeated viewing of two different cartoon episodes with her two young daughters, ages three and four. For thirty-minutes three times a week over a sixweek period, the author/researcher observed Elizabeth, a certified elementary teacher who also holds a master’s degree in education, use guided repeated viewings of a cartoon to assist her two preschool daughters in responding to questions and statements using content from the cartoons.

During the observations, the author/researcher also observed Elizabeth assisting her daughters in transferring their learning from the cartoon viewing into the critical understanding of ageappropriate print sources, such as children’s books by seeking responses to items such as “Why was the decision helpful to others in the story?” Observation items were taken from the Oral Language subsection of the Circle Classroom Observation Tool (Children’s Learning Institute, 2016). The observation items used to observe Elizabeth frame the conversations with her daughters about events in the cartoons were naming and labeling items, describing the appearance of items, comparing and contrasting items, inferencing and making judgments, and linking and making connections from previous events from the cartoons. From a young child’s perspective, watching a favorite cartoon is fun and meaningful, and this interest promoted the requests of Monty and Margie to have repeated viewings of their favorite cartoons. The CogAT Kindergarten Test: Cognitive Abilities Test was used for the pre-test and post-test. This test is used to assess children’s reasoning and problem-solving abilities.

Data Collection

Assessments Used

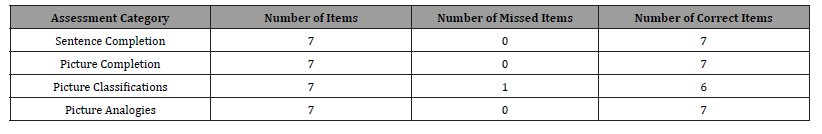

The author/researcher received permission to visit the home to administer the pre-tests and the post-tests. The assessment location was the table in the family’s dining room. Table 1 provides pre-test data for Monty on the four assessment categories, and Table 2 provides post-test data for Monty on the four assessment categories. The data sets indicate a gain for Monty in each category of the post-test.

Table 1:CogAT Kindergarten Test - Pre-test Data for Monty (4 years-old).

Table 2:CogAT Kindergarten Test - Post-test Data for Monty (4 years-old).

The examples below of Monty’s dialogic exchanges show her responses following the first viewing of the cartoon and the third viewing of the cartoon. This viewing schedule was repeated for three weeks before introducing the second cartoon episode.

Examples of Dialogic Exchanges (1st viewing and 3rd viewing)

• Let’s talk about the things you remember happening in

this cartoon.

First Cartoon Viewing: Four things were remembered.

Third Cartoon Viewing: Eight things were remembered.

• What problem did the pups need to solve?

First Cartoon Viewing: The response contained five words.

Third Cartoon Viewing: The response contained nine words.

• Let’s talk about possible solutions the pups could use to

solve the problem.

First Cartoon Viewing: One solution was provided.

Third Cartoon Viewing: Three solutions were provided.

• What did you notice about the environment?

First Cartoon Viewing: Two descriptions were provided.

Third Cartoon Viewing: Six descriptions were provided.

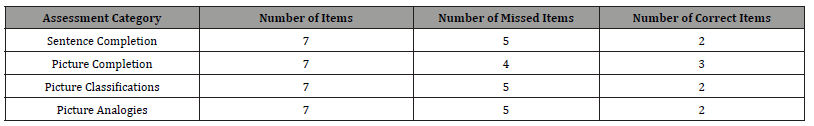

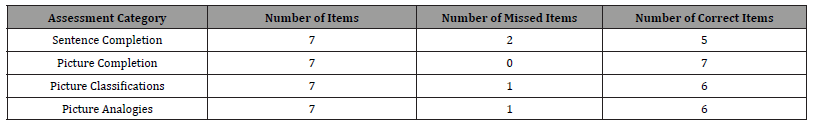

Table 3 provides pre-test data for Margie on the four assessment categories, and Table 4 provides post-test data for Margie on the four assessment categories. The data sets indicate a gain for Margie in each category of the post-test.

Table 3:CogAT Kindergarten Test - Pre-test Data for Margie (3 years-old).

Table 4:CogAT Kindergarten Test - Post-test Data for Margie (3 years-old).

The examples below of Margie’s dialogic exchanges show her responses following the first viewing of the cartoon and the third viewing of the cartoon. This viewing schedule was repeated for three weeks before introducing the second cartoon episode.

Examples of Dialogic Exchanges (1st viewing and 3rd viewing)

• Let’s talk about the things you remember happening in

this cartoon.

First Cartoon Viewing: Two things were remembered.

Third Cartoon Viewing: Seven things were remembered.

• What problem did the pups need to solve?

First Cartoon Viewing: The response contained three words,

and a correct response.

Third Cartoon Viewing: The response contained seven words,

and a correct response.

• Let’s talk about possible solutions the pups could use to

solve the problem.

First Cartoon Viewing: One solution was provided.

Third Cartoon Viewing: Two solutions were provided.

• What did you notice about the environment?

First Cartoon Viewing: Two descriptions were provided.

Third Cartoon Viewing: Four descriptions were provided.

The children’s post-test results and dialogic exchange responses indicated an increase in their understanding of the concepts related to the cartoons. The CogAT Kindergarten Test: Cognitive Abilities Test provided evidence of growth for both children in the five categories. Following the third repeated viewing of the cartoon episode, responses to the dialogic items showed an increase in descriptive responses provided by the children when prompted by their mother.

A Summary of an Observation and Dialogic Exchanges with a Parent and Her Daughters During the Viewing of a Repeated Cartoon Episode

Following a morning of routine activities, Monty and Margie prepared to watch a cartoon they had previously watched with their mother. Elizabeth began a conversation with her daughters about a general discussion of their favorite cartoon, PAW Patrol. Elizabeth said, “Today we are going to watch, again, ‘Pups Save High Flying Skye: Pups Go for the Gold.’” The girls screamed, “We’re going to watch the one about the gold nugget.”

Elizabeth had already planned how she would guide her daughters through a purposeful repeated viewing and a dialogic exchange about the content found in this cartoon episode. As she prepared to replay a viewing of the cartoon, Elizabeth discussed with the girls their thoughts about the other two times they watched this particular cartoon episode, and she gave them an opportunity to talk about the details they remembered happening in this cartoon episode. The children provided their thoughts and were excited to re-watch the cartoon with Elizabeth asking them to look at the details of the setting, to look at the number of pups in the cartoon, and to think about what happens first to start the problem that needed to be solved.

After they watched the first part of the cartoon, a commercial appeared. The commercial period gave Elizabeth time to discuss what had happened so far in the cartoon, to respond to some of the purpose-setting ideas she gave Monty and Margie to consider at the beginning of the viewing of the cartoon, and to ask her daughters to think about ways the pups could solve the problem that would be helpful to everyone in the Adventure Bay community. Since this was the third repeated viewing of the cartoon, this allowed Elizabeth to guide her daughters to expand their thinking about the events by asking them to respond to items such as: What could you make with a gold nugget like the one the pups helped find? and tell me about different hidden treasures the pups could help others find. She was asking them to make predictions and connections beyond the content of the cartoon. This type of questioning and thinking can easily transfer to other academic situations such as the repeated reading of a book or the repeated viewing of a video.

Guided repeated viewing of cartoons was designed by Elizabeth

to use as a fun family activity for the purpose of supporting the

academic growth of her children. I observed that during the

repeated viewing of the cartoon, the girls often cheered at their

favorite parts. Elizabeth frequently paused during viewings so

that she could talk with Monty and Margie about the events in

the cartoon. At the end of several observed repeated viewing of

the cartoon, Elizabeth had a discussion with the daughters that

included talking about the fun parts of the cartoon and asking if

they would like to watch the cartoon again later. Although Elizabeth

tended to design the discussion using authentic items, she also used

information from the Center for Media Literacy (2005) to develop

the items she used for the dialogic exchanges with her daughters.

Elizabeth used the following items to frame the discussion with her

daughters:

• Let’s talk about the things you remember happening in

this cartoon.

• Let’s talk about the things you saw happening at the

beginning of the cartoon.

• What problem did the pups need to solve?

• Let’s talk about possible solutions the pups could use to

solve the problem.

• Do you think the adventures in the cartoon happened

during the morning or afternoon, and why do you think this?

• What did you notice about the environment?

• How did the pups finally solve the problem?

• Tell me about your favorite part of the cartoon.

The effectiveness of guided retellings has historical significance and was introduced in 1986 by Morrow who used prompts to encourage and to engage thinking among students. As retellings are linked to repetition of content, Samuel [10] also used this concept to support thinking and verbal collaboration among students. Educators have added visual cues to support written text-sources and to make text-sources less abstract [22,23]. Repeated viewings of television cartoons, or other child-appropriate viewing of television programs or videos, can also provide visual clues to support the retelling of events to support oral language development and content understanding. Guided repeated viewing of a cartoon can be used to provide additional opportunities to deepen comprehension and to enhance academic vocabulary development. In the era of standards and assessments, attention has been placed on language development and the usage of oral discourse.

NOTE: The questions and statements used for dialogical exchanges between the mother and her children during and following the guided repeated viewing of the cartoon presented in this article would use the same procedure as if a printed literature source, a content text-source, or other media sources had been used.

A Conversation with Elizabeth: What has she noticed?

Elizabeth believes Monty and Margie are beginning to develop the skills to become critical viewers of the cartoons they watch. They are also learning to become critical listeners of oral context during reading time of printed literature during story time in the home and at the local library. Elizabeth provided this example: The girls visited their local library for a story telling hour. On the first day, the librarian introduced and read the book Kittens by Laura Ellen Anderson. On the next day, the girls went back to the library for another story telling hour. When the librarian introduced the book for this day as Pete the Cat: I Love My White Shoes by Eric Litwin, her three-year-old daughter, Margie, immediately said, “Excuse me, you read us a book yesterday about a cat.” The librarian smiled and said, “Yes, I did.”

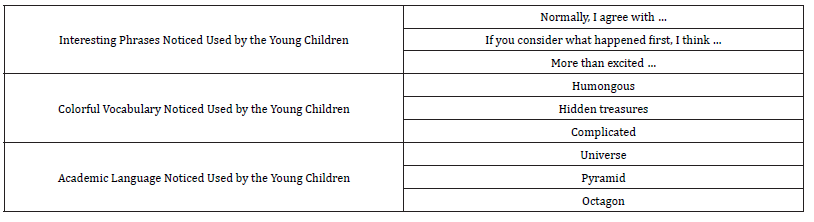

Elizabeth has noticed her daughters often engage in thoughtful discussions about other cartoons and about books that are read to them. Elizabeth has also noticed that her daughters use interesting phrases, colorful vocabulary, and academic language during discussions prompted by the repeated viewings of cartoons. She provided several examples of oral language examples she has noticed the girls using during the cartoon viewings, during book discussions, and in general discussions in Table 5.

Table 5:CogAT Kindergarten Test - Post-test Data for Margie (3 years-old).

Practical Implications

The viewing of television cartoons and especially the application of repeated viewings of these cartoons, with purposeful discussions, emphasized the interconnectedness among listening skills, oral language development, and critical thinking skills to show how the repeated viewings of television cartoons links these skills to a teachable format. Just as the parent highlighted in this article has identified a fun home activity using repeated television cartoon viewing with dialogic exchanges, other parents, educators, and caretakers can use this activity with children in home settings, school settings, and in day care centers. To guide future useful practice of using repeated viewing of television cartoons with dialogic exchanges used with young children, a list of four cartoons and their descriptions are provided for consideration.

Berenstain Bears

This is an animated cartoon for children based on a series of books by the same title as the cartoon. In this cartoon, a sister and brother bear attend school where they learn lessons about being kind to others, about being responsible for their actions, and about other lessons that promote good intentions.

Curious George

This is an animated children’s cartoon based on the book titled Curious George by H. A. Rey. The main character is George, a monkey, who often causes accidental situations that result in the need to identify a solution. The other characters in the cartoon use George as a teachable character by providing him with meaningful solutions for his problematic situations while also providing him with new learning concepts.

Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood

This cartoon is based on the concepts that were presented in the Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood series. It teaches young children about enjoying their neighbors while also learning about being nice, about being respectful to others, and about being kind to others.

Pocoyo

This cartoon highlights a 4-year-old boy who interacts with his friends: Pato (a duck), Elly (an elephant), and Loula (a dog). Pocoyo and his friends learn new concepts by understanding how to solve the situations they encounter in their environment. During the presentation of the cartoon, the narrator speaks directly to the characters and to the viewers to explain the concepts presented in the cartoon.

Final Thoughts

Young children are interested in the colorful graphics, memorable characters, and exciting episodes of television cartoons. Cartoon stories are arranged sequentially, and their animated characters tell the stories through age-appropriate short dialogue segments for their young viewers [24]. The range of cartoon content can include cultural awareness, literacy skills, STEM-information, academic vocabulary and content, the purpose of sharing with others, community helpers, and animal care along with many other subjects by providing information through visual cues, animated presentations, narrator, and voice presentations, sequentially presented concepts, and music.

When using guided repeated cartoon viewings with young children, the predictability of repeated episodes can assist with vocabulary growth and comprehension development [11]. Elizabeth has noticed a carryover of Monty and Margie’s cartoon viewing into an awareness and a deeper interest in books read to them, to movie viewing, and to discussions about various cartoonrelated topics brought up in the home, on the playground, and with their peers. She does realize that the achievement growth of Monty and Margie’s oral language and general environmental awareness can be due to other factors such as home and environmental exposure as well as to the use of the guided repeated viewing of cartoons. Elizabeth plans to continue using her daughters’ interest in television media presented through the visual delivery of cartoon episodes as a home activity to enhance their academic achievement.

There is a need for more research-based investigating and reporting about the use of television viewing among all levels of learners. The use of guided repeated viewings of television cartoons as a way to cognitively engage young children needs to be researched and reported in the literature. This article is written to provide parents, educators, and caregivers with a process of embracing the interest in cartoons among children by allowing children to be invited to engage in a productive conversation about the ideas presented through the repeated viewings of television cartoons.

I asked Margie if she enjoys talking about her favorite cartoon with her mother and sister and her response was, “It’s awesome talking about my favorite cartoon characters with mom and my sister.” Monty was asked the same question, and her response was, “I enjoy talking to mom and Margie. But I love, love watching my favorite cartoon and talking about the adventures of my favorite characters” [25-29].

Declaration Of Interest Statement

The author whose name is listed below certifies that there is NO affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria, funded or unfunded grants, participation in speaker’s bureaus, equity interests, or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interests in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Declaration Of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest.

References

- Dickinson DD, Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K (2010) Speaking out for language: Why language is central to reading development. Educational Researcher 39(4): 305-310.

- Gardner-Neblett N, Iruka IU (2015) Oral narrative skills: Explaining the language-Emergent literacy link by race/ethnicity and SES. Developmental Psychology 1(7): 889-904.

- Reed J, Lee E (2020) The importance of oral language development in young literacy learners: Children need to be seen and heard. Dimensions 48(3): 6-9.

- Copple C, Bredekamp S (2009) Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. (3rd ed.). Washington DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Yeste G, Gairal Casadó R, Munté Pascual A, Plaja Viñas T (2018) Dialogic literary gatherings and out‐of‐home childcare: Creation of new meanings through classic literature. Child & Family Social Work 23(1): 62-70.

- Elango S, Garcia JL, Heckman JJ, Hojman A (2015) Early childhood education: Working Paper Series. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Neuman SB, Dickinson DK (Eds.) (2011) Handbook of Early Literacy Research, New York, NY:Guilford Press. 3(3).

- Morrow LM (1986) Effects of structural guidance in story retelling on children’s dictation of original stories. Journal of Reading Behavior 19(2): 136-152.

- Klinkenborg V (2009) Some thoughts on the pleasure of being a re-reader. The New York Times, p. A18.

- Samuels SJ (1979) The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher 32(4): 403-408.

- Monobe G, Bintz WP, McTeer JS (2017) Developing English learners’ reading confidence with whole class repeated reading. The Reading Teacher 71(3): 347-350.

- Therrien WJ (2004) Fluency and comprehension gains as a result of repeated reading: A meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education 25(4): 252-261.

- Morowatisharifabad MA, Karimi M, Ghorbanzadeh F (2015) Watching television with kids: How much and why? Journal of Education and Health Promotion 4: 36.

- (2017) Nielsen Estimates 119.6 million TV Homes in the U.S. for the 2017-2018 TV Season.

- Hutchison LF (2015) Using television viewing to assist with enhancing literacy. In CS White (Ed.), Critical qualitative research in social education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Press.

- Hutchison LF (1989) Since they are going to watch TV anyway, why not connect it to reading? Reading World 28(3): 236-239. Abrahamson R (Ed.). Books for You. Hutchison LF (1987) Adult Reading Section, NCTE.

- Coleman G (2010) Ethnographic approaches to digital media. Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 487-505.

- Moses AM (2008) Impacts of television viewing on young children’s literacy development in the USA: A review of the literature. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 8(1): 67-102.

- Strouse G (2012) Parent-led discussion enhances children’s learning from television.

- Hart B, Risley TR (1995) Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookers Publishing Company.

- Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M Cole, V John-Steiner, S Scribner, E Souberman, Eds. & Trans.) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Duke NK, Pearson PD (2009) Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. Journal of Education 189(1-2): 107-122.

- Fisher D, Frey N (2008) What does it take to create skilled readers? Facilitating the transfer and application of literacy strategies. Voices from the Middle 15(4): 16-22.

- Dowhower SL (1994) Repeated reading revisited: Research into practice. Reading & Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties 10(4): 343–358.

- Center for Media Literacy (2005) Five key questions of media literacy.

- Children’s Learning Institute (2016) Circle Classroom Observation Tool. Houston, TX: University of Texas Health Science Center.

- Korat O, Kozlov-Peretz O, Segal-Drori O (2017) Repeated E-book reading and its contribution to learning new words among kindergartners. Journal of Education and Training Studies 5(7).

- Levy BA, Nicholls A, Kohen D (1993) Repeated readings: Process benefits for good and poor readers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 56(3): 303-327.

- Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA (2005) Children’s television viewing and cognitive outcomes: A longitudinal analysis of national data. Arch Pediatric Adolescent Medicine 159(7): 619-625.

-

Laveria F Hutchison*. Using Repeated Viewings of Television Cartoons to Enhance Dialogic Exchanges Between a Parent and Preschool Children. Iris J of Edu & Res. 2(4): 2024. IJER.MS.ID.000545.

-

Dialogic exchange, Oral language, Repeated viewing, Cartoons, Cognitive development

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.