Research Article

Research Article

Redefining Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Effective Communication and Continuous Assessment for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Success

Dr. Gayathree Mohan*

Post-doctoral Fellow, Department of Physics, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

Corresponding AuthorDr. Gayathree Mohan, Post-doctoral Fellow, Department of Physics, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

Received Date:June 08, 2025; Published Date:June 16, 2025

Summary

CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) courses in science pose significant challenges, as students must master both content-obligatory and content-compatible language. This often leads to a compromise in the communicative and collaborative strategies essential for EFL (English as a Foreign Language) learners. To address these challenges, extensive planning is essential for both learners’ input and output. Furthermore, CLIL assessments require differentiated task-based learning, which evaluates communication, cognitive skills, and learners’ attitudes. Balancing these demands necessitates innovative approaches to ensure effective content and language acquisition while preserving key communicative and collaborative elements. To tackle these issues, a foreign teacher with a Ph.D. in Physics and a 120-hour TEFL certification developed innovative strategies for a Books & Newspaper Discussion EMI course. The objective was to integrate communicative and collaborative strategies while enhancing assessments for learners at various proficiency levels. Continuous formative assessments, along with summative assessments at the end of the semester, were utilized to evaluate learning objectives. Rubrics and self-assessments were introduced to help learners identify their strengths and weaknesses. Pre-test, mid-semester feedback, and post-test questionnaires, combined with learners’ formative and summative assessments, demonstrate that diversifying learning methods enhances overall learning effectiveness. Additionally, incorporating formative assessment into CLIL helps introduce cultural and communicative components, thereby improving new learning methods.

Introduction

CLIL courses aim to simultaneously teach subject content and a foreign language. However, this approach often sacrifices a communicative and collaborative strategy for English as a foreign language (EFL) learners. Learners need to master both contentobligatory (subject-specific) vocabulary and content-compatible (non-subject-specific) language learned in English classes to communicate effectively about their curricular subjects. According to Dale & Tanner [1], significant planning is required regarding learners’ input, whether it is presented orally, in writing on paper, or electronically. Will the work involve the whole class, groups, or pairs? Will it include a practical demonstration? A great deal of effort is also necessary for learners’ output, whether they will communicate orally, in writing, or through practical skills, and what successful outcomes will look like. Performance assessments in CLIL courses involve considerable differentiation and can include individuals, pairs, or groups. Since CLIL encourages task-based learning, learners should demonstrate their skills both individually and collaboratively. These assessments can evaluate not only communication and cognitive skills but also learners’ attitudes toward learning. Teachers implementing CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) face several challenges. (1) Many educators struggle with their proficiency in the target language, making it difficult to teach both subject content and language effectively [2]. (2) CLIL requires a balance between content and language instruction, demanding specialized teaching strategies that differ from traditional subject teaching [2]. (3) Evaluating both content knowledge and language proficiency simultaneously can be complex, requiring innovative assessment methods [2]. (4) Teachers often lack access to adequate teaching materials, professional development, and institutional support to implement CLIL successfully [3]. (5) Adapting CLIL to different proficiency levels while maintaining student motivation and engagement is a significant challenge [4].

To address challenges in CLIL teaching, a foreign teacher with a Ph.D. in Physics and a 120-hour TEFL certification designed innovative methods to enhance learning, building on her previous implementation of the same Books & Newspaper Discussion course as an English medium of instruction (EMI) [5]. The aim was to integrate communicative and collaborative strategies and improve assessments of content knowledge and language skills for learners at different proficiency levels. Effective communication is key in language learning, and a CLIL course focused solely on content and language, without this aspect, is ineffective. Continuous (formative) assessment with ongoing feedback helps students track their progress. A summative assessment at the end of the semester evaluates whether learning objectives have been met. Additionally, learners should be aware of their strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, rubrics for each aspect of the summative assessment were introduced, and learners performed self-assessments on their final term papers and oral presentations.

Methodology

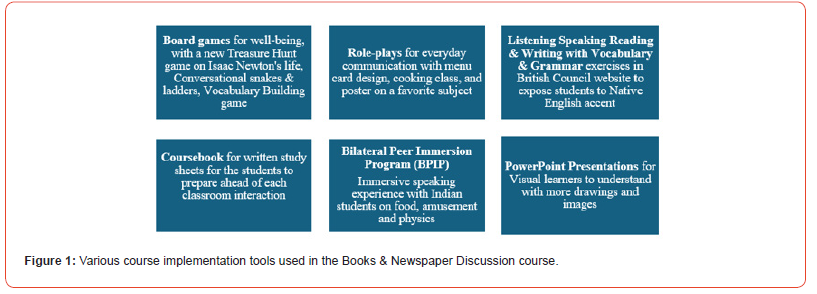

A pre-test questionnaire with A1 CEFR level foreign language questions, content questions, and student motivations for learning the foreign language and their expectations of the CLIL course was recorded. All 25 Students’ CEFR ratings were assessed in the classroom with standard CEFR rating tests available on the British Council website. Students were asked to register with their email and take the standardized test to assess their CEFR rating. Each of the 15-week, two-hour sessions was designed with the first hour dedicated to content (term paper, oral presentation, PowerPoint, abstract) and the second hour to listening, speaking, reading, and writing (LSRW) activities for continuous assessment. Various learning methods were used, including board games, the Bilateral Peer Immersion Program (BPIP) [6], role plays, speaking challenges, treasure hunt games, conversational snakes and ladders, vocabulary-building games, and writing challenges. For summative assessment, students worked on term papers, oral presentations, PowerPoint slides, talk reports, abstracts in English and Chinese, and online board games with self-assessment rubrics. Mid-semester feedback was collected, and a post-test questionnaire was administered after final presentations to measure learning effectiveness and gather feedback on the different learning methods used. The midsemester feedback consisted of two kinds of feedback from the students for each learning method used. One was on a Likert scale to arrive at a percentage, and the other was open-ended questions about each learning method used. The various learning methods or course implementation tools used in the Books & Newspaper Discussion course, along with the main reason for their use, are shown in Figure 1. A new card game of treasure hunt on Newton’s life was introduced this semester, along with roleplays to address the communication and collaboration aspects of CLIL learning. The bilateral Peer Immersion Program (BPIP) was introduced in the previous semester, with Indian students meeting Taiwanese students in public spaces like a hot-pot restaurant and an amusement park in Taiwan. But in the present implementation of the BPIP, the Indian students were inside the classrooms making their research paper presentations, sharing Taiwanese food, and playing card games with the Taiwanese students. The idea was to create a more controlled atmosphere, measure the kind of conversations the students had, and calculate the lexical density of the conversations.

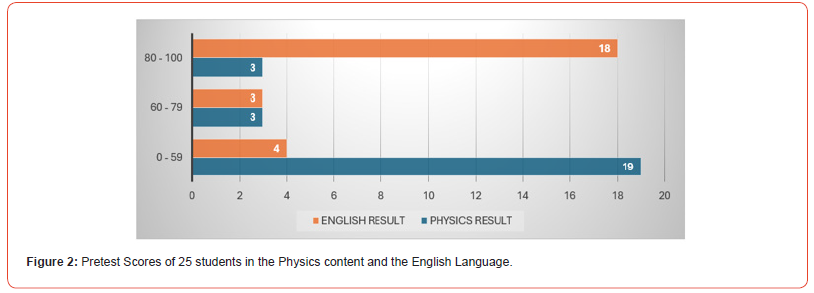

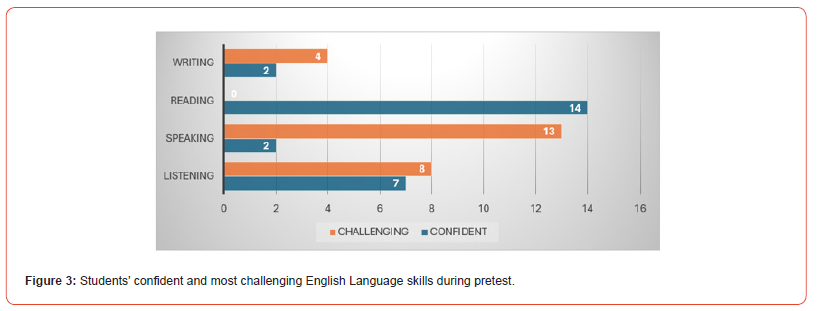

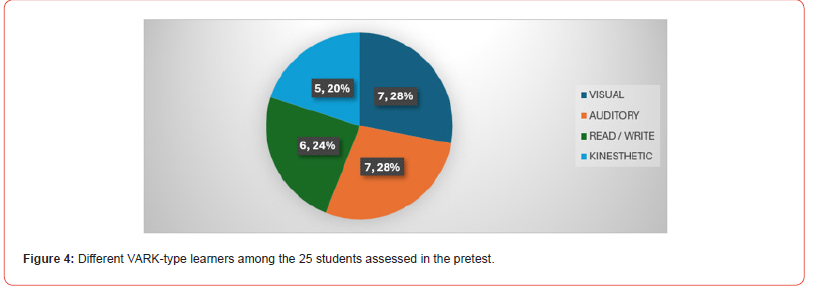

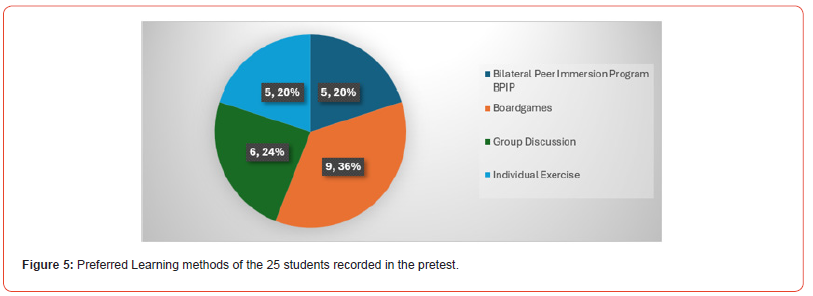

Results: Figure 2 shows the pretest results of the physics content and the English language questions. The motivation for taking up the EMI course was career advancement for 14 students and out of personal interest for the remaining 11 students. Also, obtaining feedback on their English skills was the expectation of 17 students, with 5 of them relying more on homework assignments and the remaining 3 putting their trust in the interactive sessions that the EMI course could offer to improve their language skills. About 12 students assessed their language skills as beginner level, 12 students had assessed their language skills as intermediate level, and only one student had assessed his level to be advanced in the entire class of 25 students. Figure 3 shows the confident and most challenging English language skills of the 25 students. Figure 4 shows the different types of learners in the VARK style [7] to plan the course materials accordingly. Figure 5 shows the learning method preference of the 25 students.

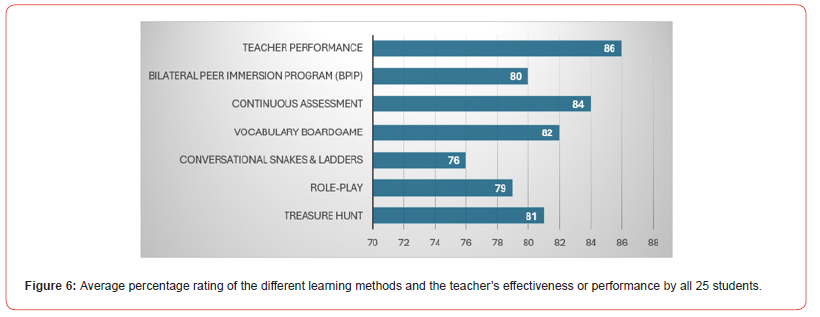

The midsemester feedback form was administered with a pen and paper with the help of the teaching assistant and showed the students’ ranking of the learning methods used and some openended comments about each learning method discussing the most challenging part of the learning method, on how the learning method could be improved and which English skill it helped the learners improve. The midsemester feedback also had a few questions on the teacher’s effectiveness, with a Likert scale to arrive at a percentage. Figure 6 gives the average percentage rating of the different learning methods and the teacher effectiveness.

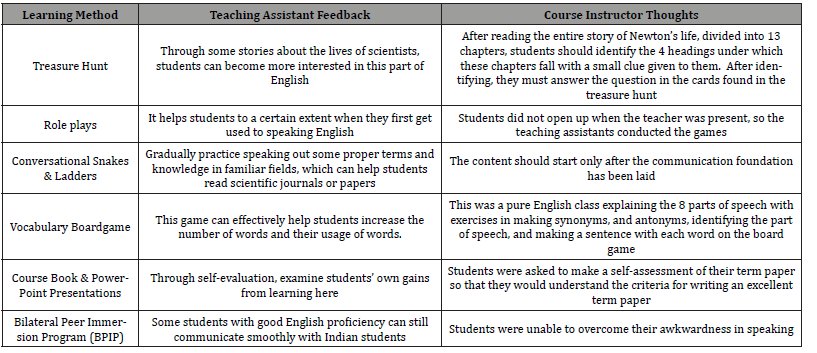

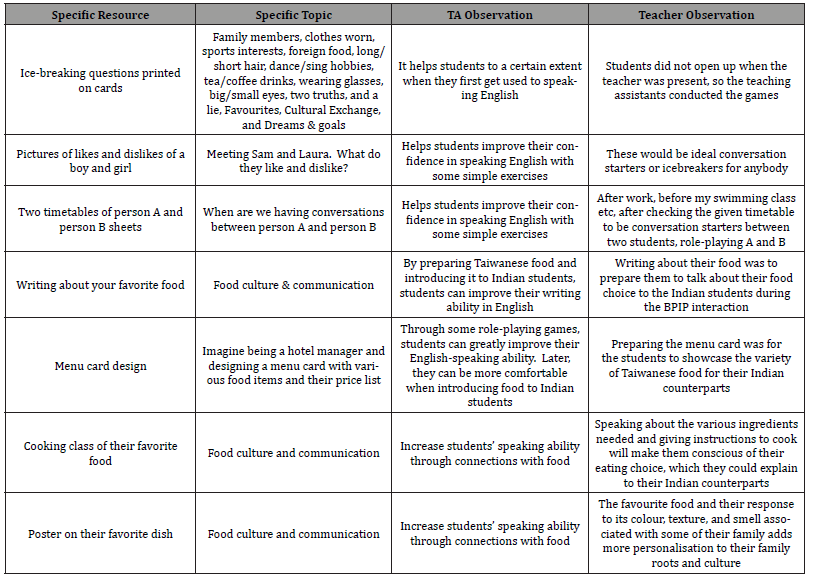

Table 1 shows the feedback of the teaching assistant, foreign teacher, or course instructor on the various learning methods used in implementing the Books & Newspaper Discussion course.

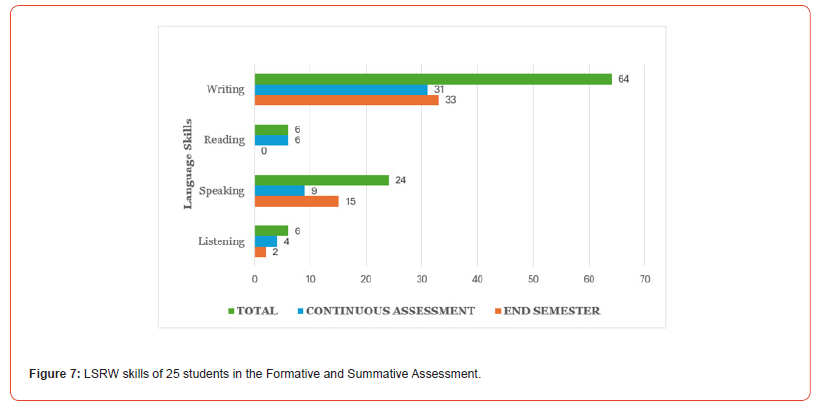

Figure 7 shows the 4 language skills of the 25 students in the Summative (End Semester), Formative (Continuous Assessment), and combined assessment of the students.

Table 1:Teaching Assistant Feedback and Course Instructor Reflections on the different learning methods used in the Books & Newspaper Discussion EMI Course.

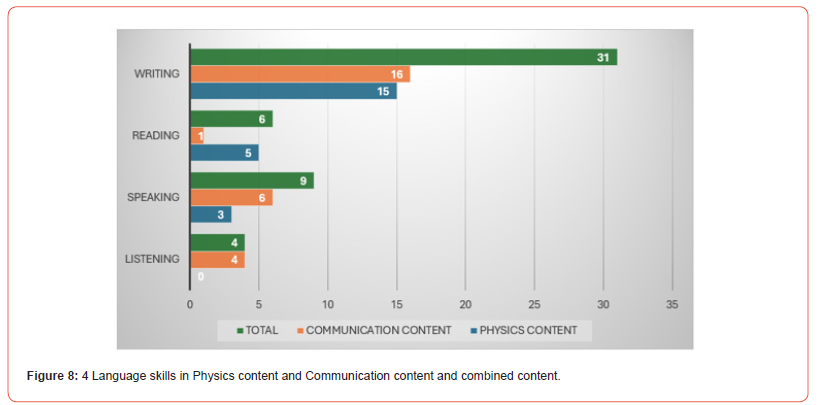

Figure 8 shows the 4 language skills in Physics and Communication and finally the total of both the content.

Table 2 shows the various communication content introduced in the Books & Newspaper Discussion course along with the comments of the teaching assistant and the reflections of the course instructor

Table 2:Communication content with comments of the TA and course instructor.

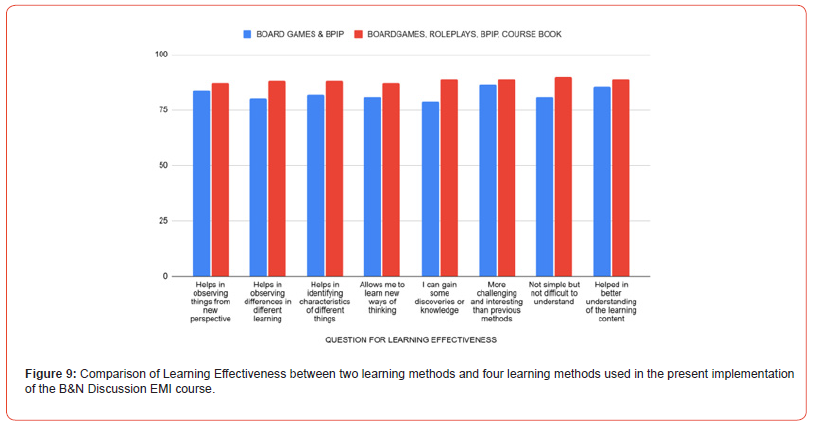

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the learning effectiveness between the present semester, where 4 new learning methods were used, against the previous semester of the same Books & Newspaper Discussion course to a different set of students where only 2 learning methods were used.

Discussion

In Figure 2 from the pretest questionnaire, the students performed very badly in the Physics content part, with 19 out of 25 students in the lowest mark range of 0 – 59%. This may be because the questions and problems selected required extensive knowledge of Content-Obligatory words in English, which was extremely tough for the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students who had learned Physics in their first language, L1, which was Mandarin Chinese. The English result in Figure 2 was high, where 18 out of 25 students had scored in the highest mark range of 80 – 100%. This may also be because the level of questions in the foreign language (FL) was at the lowest A1 CEFR level, which most of the learners were able to achieve. From Figure 3, we can see that 14 out of 25 students were confident in their reading skills, but 13 out of 25 students found speaking skills to be the most challenging skill in the foreign language (FL). So, most of the course implementation strategies were designed to make the Taiwanese students speak more in a foreign language (FL). Figure 4 shows that 28% of learners preferred auditory and visual methods, followed by 24% of Read / Write learners and 20% of kinaesthetic learners, or learners learning by doing. So, extensive oral lectures for auditory learners were given with PowerPoint presentations for visual learners and a coursebook for the Read / Write learners. From Figure 5, we can see that an overwhelming 36% of learners preferred the use of board games as it brings their competitive spirit, adding more feelgood and entertainment value to their learning. 24% of learners preferred group discussion 20% of learners preferred individual exercise, and another 20% of learners preferred the Bilateral Peer Immersion Program (BPIP) with conversations with foreign students. From Figure 6, we can see that the teacher’s performance was the highest at 86% for having introduced different learning methods inside the classroom. Formative assessments or continuous assessments had an 84% rating from the students, due to which several new learning methods could be introduced, and assessment of those learning methods could be taken, as only the summative assessment would lead to a monotony in terms of the tasks that were planned in the classroom. Among the various learning methods used, the vocabulary board game scored the highest at 82%, as it was ideal for the EFL students to learn contentcompatible words or everyday functional language, and the 8 parts of speech essential to speak/read/write in English. The vocabulary board game was closely followed by the treasure hunt card game, as it was based on Sir. Isaac Newton’s life history, involving his contributions to Physics, was appreciated by the students. Next was the BPIP with 80%, followed by role-play with 79%, and finally the conversational snakes & ladders board game at 76%. With all the learning methods, the learners could have performed better with some scaffolding, which is the most important aspect of EFL learning, that was completely missed by the teacher. Figure 7 shows that writing tasks in the formative and summative assessments were more and there was no reading skill tested in the summative assessment, and the least employed skill was the listening skill. So future implementation of the Books & Newspaper Discussion course should include more listening and reading components. The talk reports submitted with the listening activity were done in the absence of the course instructor. So, it became difficult to assess the student’s report without the instructor listening to the lecture. In the future, the instructor should listen to all these lectures organized by the department, for a proper evaluation and feedback for the learners. Figure 8 shows an equal amount of the communication content introduced along with the extensive physics-related content for the 4 different English skills. Table 2 shows the various food, culture, and communication aspects introduced into the curriculum to make everyday communication in the foreign language (FL) easy for the learners. Figure 9 shows the learning effectiveness questions response from the post-test questionnaire, with a comparison of the previous implementation of the same B&N Discussion course with a lesser number of learning methods with a different batch of students. Figure 9 also proves to us that the learning effectiveness is directly proportional to the number of learning methods used in the course. The learning effectiveness is higher when 4 learning methods are used than the learning effectiveness when 2 learning methods are used. Different learning methods benefit different learners.

Conclusion

The introduction of Formative Assessment into CLIL helps introduce culture and communication components, thus enhancing the newer learning methods. Diversifying learning methods enhances overall learning effectiveness and significantly boosts course attendance. Listening skill assessment weightage is to be enhanced with the talk reports inside the classroom or the teacher attending the talks organized by the department. Writing skills had maximum weightage in both the formative and summative assessments is to be reduced. Scaffolding is to be introduced at various levels. Scaffolding in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching is a method that provides learners with temporary support to help them acquire new language skills. This support can include modelling, prompting, visual aids, language frames, and interactive activities. The goal is to gradually remove the support as learners become more confident and capable, ultimately promoting active learning, enhancing understanding, and supporting individual progress. In essence, scaffolding bridges the gap between what learners know and what they are trying to learn. More self-study and clearer planning of coursework and game dynamics are required for better implementation of the course objectives.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in this research work.

Funding

This work was generously supported by the private university grant number 1679.

Acknowledgement

I thank the Department of Physics, National Taiwan Normal University, which supported me with a generous post-doctoral fellowship for this study.

References

- Dale L, Tanner R (2012) Teaching science through English: A CLIL approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Cañado MLP (2018) Innovations and challenges in CLIL teacher training. Theory Into Practice 57(3): 212–221.

- Jung SY, Su SW, Yu X, Yuan SM, Sun CT (2023) Willingness, proficiency, or support? Challenges in implementing content and language integrated learning for Taiwan K-12 teachers. Engineering Proceedings 55(1): 10.

- Wang M, Muñoz KE, Yang W (2024) What happens to CLIL teachers in classrooms after professional development? A transformation of conceptualising the CLIL approach and language instructional strategies. English Teaching & Learning.

- Mohan G, Rajeshwari R (2024) Board games as content and language-integrated teaching and assessment tool for EFL students in Taiwan. Journal of Foreign Language Education and Technology 9(1).

- Mohan G, Rajeshwari R (2025) Bilateral Peer Immersion Program (BPIP): A CLT tool in a CLIL course. Journal of English Language Teaching 67(1): 36–42.

- Fleming N (2012) VARK: A Guide to Learning Styles.

-

Dr. Gayathree Mohan*. Redefining Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Effective Communication and Continuous Assessment for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Success. Iris J of Edu & Res. 5(1): 2025. IJER.MS.ID.000605.

-

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), English as a Foreign Language (EFL), Learning, English medium of instruction (EMI), listening, speaking, reading, and writing (LSRW)

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.