Review Article

Review Article

The Dynamics of Qiaoxiang Spatial Cultural Resources Integration - Taking Jiangmen City as an Example

Tian Yang1 and Le Gao2*

1Guangdong Qiaoxiang Culture Research Center, Wuyi University, China

2Department of Intelligent Manufacturing, Wuyi University, China

Le Gao, Department of Intelligent Manufacturing, Wuyi University, China.

Received Date: January 15, 2021; Published Date: January 25, 2021

Abstract

This paper starting from the overseas Chinese building complex in Jiangmen -- 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street to approach the topic with the cultural resources in the hometown of overseas Chinese (Qiaoxiang). By exploring the past and future of Qiaoxiang resources in the form of overseas Chinese architecture, this paper tries to outline the cultural spiritual value of overseas Chinese life aesthetics in the context of globalization, based on the practice and dynamic value of cultural resources beyond the geographical material space generated by the dual function of traditional local values and western culture. It reveals the traditional concept, geographical concept and realistic intention of the people behind the overseas Chinese architecture in the specific historical background. As a dynamic cultural symbol, Qiaoxiang is not recognized by people through the architecture of overseas Chinese but sublimates the whole hometown resources into a whole cultural symbol of Qiaoxiang.

Keywords:Cultural resources; Space; Folklorism; Cultural memory

Introduction

Hometown is the field of people’s life, and culture “becomes a resource” dynamically in the basic social field (Zimmerman, 1933). As a “big field”, a highly differentiated society is composed of some independent and interrelated “sub fields”. Therefore, field can be defined as a “network” or a “configuration” of objective relations between various positions [1]. Cultural resources are not only used for cultural practice in the “instantaneous cultural resources” as a daily field, but also need to be developed and utilized in a larger national field and market level [2]. Then, as Qiaoxiang in the context of globalization, the nostalgic nostalgia complex with nostalgic color is reflected in the typical folklorism. The “symbolic capital” formed by the accumulation of nostalgic and nostalgic elements bears the responsibility of modern folklorism and further constitutes the academic paradigm of modern folklore [3]. From the concept of “field”, this paper interprets the social composition of Qiaoxiang resources in the anthropological sense and emphasizes the cultural mentality of different fields in social space and the cultural perception of daily practice. With the regional development and transnational flow of Qiaoxiang in the changing times, the cultural landscape of Qiaoxiang has been continuously capitalized. In the continuous cultural construction, through the historical memory and emotional belonging of the people in Qiaoxiang, the history and culture of the “Overseas Chinese” as local knowledge are re-understood [4]. As a cultural landscape and a cultural heritage of tourism resources, Qiaoxiang plays a vital role in the cultural heritage and innovation. Under this circumstance, based on historical experience and cultural tradition, the definition of Qiaoxiang should be shifted from “economic priority” to “cultural dominance” [5].

As Qiaoxiang resources in the context of globalization, it integrates the nostalgic complex, showing the typical folklorism. In the overseas Chinese society where the resources of Qiaoxiang are accumulated as symbolic capital, the overseas Chinese of Wuyi area play an important role in promoting the transformation and accumulation of social resources of Qiaoxiang. Overseas Chinese are constantly participating in the revitalization and integration of hometown resources brought about by globalization in the way of ancestral identity. The concept of folklorism originated from German folklorist Mozer (1962), which refers to the invention and reconstruction of “traditional customs” for political and economic purposes. The theory has been critically developed by the academic circles, Bausinger accepted Kosling’s proposition and referred to Adorno’s concept of “culture industry”, and further turned the focus of attention to “folklorism” to “cultural commodity resource” [6]. Driven by the globalization of economy and culture, folklorists describe the perceptual practice of traditional nostalgia and hometown complex. With the intense development and speculative process in the academic circle, cultural researchers should pay more attention to the “folklorism process” recognized by the public and the link of constructing an “imaginary community”, and respect the important value of “the tradition of invention” in the process of shaping national identity [7-11]. The cognition of tradition should not only stay in the illusion of revivalism, but also pay attention to the meaning of reconstructing and generating new tradition? How to examine the cultural process of traditional reproduction, in fact, is to use the innovation, reconstruction and new construction of modernity to keep the new tradition in the current society?

On the whole, compared with the field of history study with productive research achievements, there are few theoretical concerns from the perspective of anthropology and folklore in the academia about the resource revival and nostalgia of Qiaoxiang. In fact, resources of Qiaoxiang have been playing an important role in the revitalization and remodeling of the traditional folk customs of overseas Chinese and their ancestral places, on the one hand, it is related to the localization of nostalgia in the process of globalization, on the other hand, due to the dual influence of traditional culture and Western values, it is significantly different from the general sense of “revitalization of traditional culture”, which needs special research. The research object of this paper is the role of Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street, the historical block of overseas Chinese, as the resources of Qiaoxiang, in the movement of traditional rejuvenation and remodeling, and the power of integration of resources and culture of Qiaoxiang formed by the continuity and expansibility of various reciprocal subjects in time and space. If it is separated from the local knowledge system of Qiaoxiang, it is difficult to grasp the dual identity and social authenticity of overseas Chinese from the perspective of history study. In this context, from the perspective of anthropology, this paper regards Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street as hometown resources, and considers the dynamic continuation, revival and production process of cultural tradition. We should expand the overseas Chinese society from the creation of cultural resources in Qiaoxiang and the background of globalization in which the overseas Chinese live. With the help of the flow of overseas Chinese between their country of residence and their hometown, a complex, pluralistic and situational social and cultural network is constructed.

From Cultural Capital to Hometown Resources

The concept of “cultural capital” was put forward by Bourdieu. As an unquantifiable symbolic capital, it has three forms: Firstly, the individual acquired education and emotional interest can share knowledge with the collective and become the collective “habitus”; Secondly, objectively, books, cultural relics and works of art constitute the factors that guide the formation of personal values and can be passed on from generation to generation in terms of materiality; Thirdly, the qualifications recognized by the society are the guarantee for the legalization of cultural capital [12]. The concept of “cultural capital” can help us to compare and clarify the relationship between Qiaoxiang resources. Both Qiaoxiang and overseas Chinese belong to the two important parts of “overseas Chinese culture”. Their distinctive regionality, the deep influence of overseas culture and the main tone of traditional culture are of great practical value. As a “living cultural form”, the culture of Qiaoxiang is the crystallization of the fusion of local culture and foreign culture in the aspects of architectural culture, values and social governance [13]. As the ancestral home of overseas Chinese, Qiaoxiang is the basic place of daily life practice for overseas Chinese and their families in the sense of space. The way of life in Qiaoxiang shows the culture and diachronic accumulation of the overseas Chinese group, which is the primary factor for the Qiaoxiang resources as cultural capital and can be inherited from generation to generation. The tangible and intangible cultural capital of Qiaoxiang will be transformed into a unique form of Qiaoxiang resources, making it a dynamic resource in the basic social field network of Qiaoxiang. Inspired by the theory of “cultural capital” and transnational consciousness, this study, on the one hand, investigates the historical and cultural resources of the overseas Chinese in Jiangmen, and tries to explore how the overseas Chinese, influenced by the traditional Confucian cosmology and Western civilization, project the aesthetics of life on the architecture of their hometown; On the other hand, this paper also expound the nostalgia complex, hometown consciousness and the revival of traditional culture in South China are the internal driving forces to promote the resource-based development of Qiaoxiang after the reform and opening up. Therefore, the cultural resources of Qiaoxiang endowed with value are the unique cultural resources of hometown accumulated by condensing the new strategy of traditional rejuvenation.

Qiaoxiang Resources: Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street

Jiangmen City has a long history. It is located at the intersection of Xijiang River and Pengjiang River in Guangdong Province, China. Because of the confrontation between Yandun Mountain and Penglai Mountain on both sides of the river, it is called “Jiangmen”, which means “gate of the river”. Jiangmen, also known as “Wuyi”, has five county-level administrative regions, namely Xinhui, Taishan, Kaiping, Enping and Heshan. It is one of the central cities of Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao. Jiangmen has a resident population of 4.5982 million, and there are also more than 4 million overseas Chinese who originally from Jiangmen, which are distributed in 107 countries and regions in the world. It is a famous Qiaoxiang in Guangdong and also known as “the first hometown of overseas Chinese”. In 1840, the Qing Empire was declining day by day. The Treaty of Beijing signed by the Opium War set off a wave that the ancestors of Wuyi went abroad to make a living as Chinese laborers on a large scale. In 1902, the 28th year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu, Jiangmen commercial port became more and more prosperous because of the Sino-British commercial treaty. As early as the end of Yuan Dynasty and the beginning of Ming Dynasty, Jiangmen market was opened by local merchants on Penglai Mountain. Because of its high terrain, it was named “Xuding” (The top of the market). By investigating the basic situation of the historical resources of Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street of Qiaoxiang in Jiangmen, it help us to understand information of the scope, quantity, historical form, affiliated institutions, operation mechanism, resource status, preservation status, users and affected people of these oversea Chinese historical Qiaoxiang resources. It is hoped that through the changes of ancient markets and the development process of modern commerce in this region, we can explore the driving force of their integration with regional social culture.

According to historical records of the Qing Dynasty, the relics of Jiangmen 33 Market Street are located in Jingguo Street, Anlongli, Jielongli and Tainingli. Today, Xuding block mainly refers to the 0.3 square kilometer Chinese Southern residential style blocks of brick and stone structure located to the east of Diaotai Road, south of Lianping road and east of Chang’an Road. Most of the names of 33 Market Street are based on the function of trading: for example, Jingguo Street used to be a market for tribute fruits, candy and traditional snacks; as the name suggests, Chicken Market is the place where chickens, ducks and birds are traded; Xinsheng Street, formerly known as Jiuluo Street, is mainly engaged in funeral goods; Yu Qingli, because of the prosperity of the market in the Qing Dynasty, the Qing government stationed Yu Qingli as a county government office for magistrate. In the field investigation, we learned that Yu Qingli used to have watchtowers and prisons for defense in Qing Dynasty. In 1913, after the government of the Republic of China cleared up the property of the old Qing empire, Yuqing company, which was formed by the members of Jiangmen chamber of Commerce, built and developed 30 two-story houses with the same pattern in four lanes and three rows in the same site. Tainingli is a place for trading tiles, poultry, vegetables and fruits; Dongnansheng street, formerly known as Ci street (rice), is mainly engaged in rice cake, etc; Anlongli, the main piglets trading; Lianping Road, a prosperous commercial street merged from Liantang street and Ping’an Street, is mainly engaged in furniture and gold ornaments; Honghua society, mainly engaged in furniture; Iron street, mainly engaged in iron; The rest, such as Chengenli, Xingning road and Yongningli, are named for their auspicious meanings. The name of Jiangmen 33 Market Street comes from the 33 stone steps down to the waterway. Because of the prosperity of Jiangmen 33 market, merchants gathered around here. People moored their boats at Shuibutou wharf and went up the stone steps to buy and sell here. Chen Xianzhang, a great scholar of Ming Dynasty, wrote poems praising the scenery at that time. There used to be Shuibutou gate on the 33 stone steps with the word “Jiangmen” engraved on the gate, which is regarded as the birthplace of Jiangmen City. Near Shuifutou stone steps; there is a well-known edge tool shop in Jiangmen, which is a witness to the prosperity of Xuding.

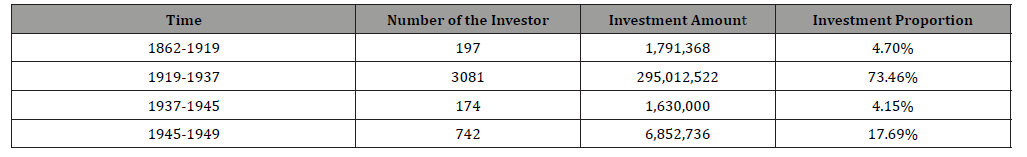

The development of Jiangmen in modern times is inseparable from the contribution of overseas Chinese. Since the opening of Jiangmen port, overseas Chinese have begun to build real estate in their hometown. At this time, most of the real estate built was concentrated by the family members of overseas Chinese, and the scale was small. However, statistics show that between 1919 and 1937, the investment ratio of overseas Chinese in Jiangmen was as high as 73.46% (Table 1). Compared with other periods, it is obviously the peak period for overseas Chinese to invest in building houses in Jiangmen. This is inseparable from the social and historical background at that time. Since the construction of Xingning railway from Taishan City to Jiangmen City North Street Railway Station in 1906, Jiangmen, as a foreign trade port, has enjoyed unprecedented prosperity. In 1925, Jiangmen was a city under the jurisdiction of the province. During the period of Chen Jitang’s administration of Guangdong Province, the national government of Guangdong Province promulgated the law of encouragement for overseas Chinese to return to China and set up industries with the main purpose of “Protecting Businessmen and Overseas Chinese” and encouraging overseas Chinese to invest. Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street were built on a large scale at this time. In 1929, Jiangmen Changdi Historic Street Qilou (arcades) commercial district began to take shape, with numerous shops and bustling business customers. At the same time, the road system around this area has also been rebuilt and widened. At that time, 900 buildings were built in Didong district and 300 in Shahang district. There were 2300 buildings was built in Jiangmen, including 1100 residential buildings and 1200 shops. In Jiangmen (Wuyi area), 44.9% of the total number of Qilou (arcades) in Guangdong Province were built by overseas Chinese. From 1937 to 1945, the construction of overseas Chinese property in Jiangmen was greatly reduced due to the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese war. It can be seen from table 1 that the number and number of households in this period are roughly the same as those in 1862-1919. It can be inferred that the injection of overseas Chinese capital at that time was not used for investment but should be used to subsidize the residence of the family members and relatives of overseas Chinese in China. Some data show that in 1947-1945, “the overseas Chinese in America, who were mainly Chinese originally from Wuyi area, contributed more than 69 million US dollars to the Anti-Japanese War to the motherland. Among them, one of the leaders of the Chinese community in the United States. He’s contributed 300000 dollars by himself”. After the war, overseas Chinese investment in construction entered a state of comprehensive recovery. In 1945, in order to rebuild the wasteland, Guangdong Province issued the “Measures of Guangdong Provincial Government for Rewarding Overseas Chinese to invest and Set up Industries”. The implementation of this policy encouraged the enthusiasm of overseas Chinese capital and promoted a new round of construction capital injection. According to the statistics of literature data, during 1945-1947, the total amount of overseas Chinese capital in their hometown further increased. The dual power of politics and economy has established Jiangmen as a regional center of Wuyi area and a transit station for the flow of overseas Chinese between their ancestral hometown and destination countries.

Table 1:Proportion of Overseas Chinese Investment in Jiangmen Real Estate Monetary. Unit: RMB.

Walking down the 33 steps to the former waterway a hundred years ago, we can get to Changdi Historic Street on the Bank of Pengjiang River by crossing Diaotai road and Xingning road with many Qilou on both sides. According to our research, the Qilou are mainly distributed in Dizhong road and Dixi road of Changdi Street, with a total length of about 2 km. The section from Shengli Bridge to Jiangli Bridge (about 1km) is a 2-4-story discontinuous Qilou mixed with traditional dwellings and modern buildings. The Qilou along the riverside has no back-street buildings and is already integrated with modern city. In contrast, from Shengli Bridge to Pengjiang bridge section (about 1 km), the magnificent Qilou buildings are well preserved, and the prosperity of that year can still be seen. Walking up from the Zhonghua Hotel, we can still see the previous names of hotels and businesses from the top of the Qilou a hundred years ago: such as Yongli Company, Zhonghua restaurant, Wanjiuxing, s Yangshengtang Hall, Dexuan company and so on. According to the historical records, most of these hotels and businesses are invested by overseas Chinese. There are more than 30 hotels near Dixi Road, among which there are seven large hotels with catering department. The famous Zhonghua hotel is one of them.

Unlike the section from Shengli Bridge to Jiangli Bridge, which has no building behind the Qilou, this section of Qilou back street extends from Zicha road to the northeast through Lianping Road, Xingning road and Taiping Road to Shangbu road. Within the area of about 0.27 square kilometers, there is no clear division standard, which is for commercial use or mixed use of commercial and residential buildings. These magnificent Qilou are different from the 2-3-story traditional Southern Chinese residential buildings and single or row residential buildings and grocery stores built by brick and wood in 33 Market Street, such as Shasanxu Street, Neijingguo street area. Qilou buildings are all used as shops. Their architectural styles are a combination of Chinese and Western styles, mainly Baroque style, Renaissance style, Roman arcade style, Lonian style and mixed with a small amount of Southern Chinese traditional style. In addition, in the area about 0.023 square kilometers north of Shangbu road and west of Yuejin Road, there are buildings of overseas Chinese and their families living in the area with wellplanned lane ways named Changleli, Daanli, Longjuli, Nanfenli and Qimingli. These 2-3-story overseas Chinese residential buildings, which were built in 1914, are overseas Chinese villages built by integrated real estate company funded by overseas Chinese for overseas Chinese families and overseas villagers near Shiwan village. As a result, together with the 2 kilometers Changdi Historic Street riverside Qilou, the 0.59 square kilometer Changdi backstreet Qilou complex, 33 Market Street and Nanfenli overseas Chinese village constitute the historical imprint and urban memory of Jiangmen City’s architectural landscape changes caused by the overseas Chinese investing in real estate in their hometown.

Qiaoxiang Resources and Nostalgia of Overseas Chinese

In the academia, the research of boundary was first regarded as a phenomenon of social differentiation in human social life, represented by the classical sociologist Durkheim, who described the natural history process with the boundary study. Simmel’s theory of “conflict” and Bourdieu’s theory of “cultural differentiation” take a different approach to regard “secular” and “sacred” as the universal boundary from the religious perspective. Weber has a great achievement in the study of social boundary; put forward the theory of social stratification to explain the diversity of social boundary. The essence of classical research regards “boundary” as an abstract spatial order and spatial relationship of social relation system. Barth creatively put forward the “knowledge boundary”, which is beyond the boundary of space society and has the ability to influence society. When discussing the construction mechanism of the boundary, Fuller regards the boundary as “the battlefield of the struggle of social relations” and thinks that the change of the boundary is the dominant factor of the complex interaction of social relations. The common point of their research is to emphasize how the social boundary is established and transformed in the interactive relationship, and how to explain complex social phenomena. The unique values formed in the cultural field maintain and adjust the resource structure of Qiaoxiang and the cultural boundary as capital.

Qiaoxiang Resources: The Spatial Field of Memory

According to research, the ratio of men to women in New York’s Chinatown was 110:1 at the beginning of the 20th century. By 1940, the ratio was 6:1. Due to the long-term serious gender imbalance of Wuyi overseas Chinese in their country of residence, it is “impossible” for most people to find a spouse, let alone “satisfactory”. In such a background, the overseas Chinese in Wuyi can only hope to find their own life partner in their hometown, so their hometown has become the pronoun of “home”. In order to support their families, Wuyi workers worked hard overseas and the rewards they earned were sent back to their wives and children. In the 1930s, half of Guangdong’s remittances came from America. In 1930, only Taishan accounted for one third of the total amount of remittances in China. It can be seen that the amount of remittances in Wuyi at that time was quite amazing. The main purpose of these remittances is to supplement the family and support the families of overseas Chinese. A large number of people in Wuyi’s Qiaoxiang depend on remittances. The construction of the space of Qiaoxiang engraves the ideology and cultural belonging, so it also pays attention to the complex response and adjustment of the early Wuyi overseas Chinese group to the boundary of home (the “two ends of home” between hometown and other places). The spatial structure is not only reflected in the obvious geographical space and political power structure, but also in the cross-border context and Qiaoxiang,i> that is, the social space of their ancestral home. The defined spatial relationship and order, as well as the social and cultural significance, are not fixed, but the continuous reproduction and reconstruction of the state and overseas Chinese groups through certain cultural resources and spatial practice.

In Qiaoxiang,i> the society interacts with the concepts of memory, tourism and cultural heritage. Qiaoxiang has become the memory field of nostalgia and culture. Therefore, the historical past of Qiaoxiang is just a “foreign country” in time, and we can still study the different types of “overseas Chinese” historical and cultural resources, beliefs, international interactive networks, kinship ties and complex social relations in the society of Qiaoxiang through the existing space resources, combined with the dual dimensions of time and space Structural and dynamic description (including Qilou, hospital, school and villa, etc. Our brain (body) connects the existing overseas Chinese buildings, such as Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street, with the existence of daily living space, that is, Qiaoxiang resources (space). On the scene, we can’t help but recall the overseas Chinese society as a culture by adding symbols to Qiaoxiang resources. The integration of the historical and cultural resources of Qiaoxiang itself is an important space field to recall culture. In this case, the space field is not recognized by people through the cultural symbol overseas Chinese architecture but sublimates the whole Qiaoxiang resources into a whole overseas Chinese cultural symbol. The production and reproduction of hometown resources is itself the production of cultural order, “culture resides in the mind”, and the culture of Qiaoxiang resources is “the social storage place of explanation mechanism and value system”. The significance of Jiangmen overseas Chinese architecture as a space cultural commemoration scene is to let the group place their unique memory in such a space which contains cultural elements of Qiaoxiang and full of humanistic nostalgia.

Nostalgia and Emotional Belonging

With its distinctive international characteristics, the culture of Qiaoxiang extends the deep nostalgia in the flow of overseas Chinese going abroad and returning home. Since modern times, the tradition of men going abroad to make a living in Wuyi area has closely linked the Qiaoxiang with the world. “The ups and downs of world economic development and political changes have a direct impact on the social changes in the hometown of overseas Chinese. If overseas Chinese sneeze, Qiaoxiang will catch a cold.” with its distinctive international characteristics, the culture of Qiaoxiang is increasingly showing nostalgia in the heart of overseas Chinese in the continuous flow of going abroad and returning home. One of the characteristics of this study is the fieldwork of Qiaoxiang. We use participatory observation and deep cultural description technology to conduct in-depth and detailed ethnographic survey and record, and solve the above key points through long-term, solid, standardized and detailed ethnographic survey and repeated comparative research, so as to determine the “local people’s point of view” in real cases and show multi-dimensional daily cultural life. To develop and promote the “soft power” of the cultural revitalization of Qiaoxiang, so as to explore and refine the cultural resources of Qiaoxiang around the nostalgia complex. The early Chinese laborers in Siyi area (Kaiping, Enping, Taishan and Xinhui) who went to the American continent to earn a living experienced the cruel anti-Chinese act of the 19th century and discrimination from the mainstream society. Most of them could not get together with their families. Most of the early immigrants who were strangers in foreign lands hoped to make money and return home as soon as possible. However, things are unpredictable, many factors make them have to settle in other places. At this time, their homeland became their dream place. In the early days, the custom of “second burial” was popular among the “Siyi” immigrants, and a special shipping company undertook the business of transporting corpses back home (Fan, 2017). Returning to the roots of fallen leaves is not only the traditional value and death view of Chinese people, but also the expression and expression of nostalgia. Although they died in a foreign land, people who still go back to their hometown will connect their bodies with their hometown in space again. Their descendants will also return to the land where their ancestors once lived in the form of “root seeking” to express their embarrassment in the country of immigration and nostalgia for their ancestors’ hometown. Therefore, the sense of nostalgia caused by globalization makes the connection between overseas Chinese and their ancestral places coincide with traditional ideas, geographical ideas and the real intention of glorifying their ancestors (Wuyi overseas Chinese family gathering, donating money to build family temples, donating to build universities and Seeking Roots Trip); the flexibility of the “traditional concept” makes the overseas Chinese identify with and extend the circle of communication (Overseas Chinese associations, guild organizations; the idea that all Chinese come from same hometown). The cultural field on which the resources of Qiaoxiang depend is the interactive process and effect with different levels of state, market, politics and economy.

Nostalgia in this sense is not just a negative emotion of morbid depression but should be seen as the search for past identity from the perspective of folklorism, and closely link the past, present and future identity construction through collective memory, social memory and family memory. Based on the current society, it dynamically and actively tangles the stable identity of the current overseas Chinese and the ever-changing identity of the future Role change [14,15]. First of all, the culture of Qiaoxiang integrated by resource-based folk customs is the link to transform the resources of hometown into cultural capital, thus promoting the revival of regional traditional culture and connecting the spirit of “root soul dream”. Therefore, Qiaoxiang resources become the humanistic field of nostalgia. The internal historical and cultural texture structure of overseas Chinese architecture space is not only reflected in the obvious geographical space and power structure, but also reflected in the transnational flow context of overseas Chinese and their homecoming identity, that is, the social identity adjustment across the ancestral space caused by nostalgia. Therefore, Qiaoxiang has become the memory field where nostalgia and culture meet. The vitality of nostalgia is rooted in the traditional Confucian culture and the cultural identity of the group [16-21]. Although the validity of tradition will be alienated and reorganized due to the change of time and space, and weakened due to the inter-generational transmission of overseas Chinese, the internal driving force of their shared identity and culture will not disappear, but will continue with the transmission of cultural memory and family memory. Secondly, from the perspective of nostalgia in the traditional sense, Qiaoxiang represents the feeling of the past and the exploration of spiritual destination. The construction of nostalgia can not only be understood through the extension of the century old overseas Chinese architecture, but also through the living and warm connotation of overseas Chinese activities such as root seeking and ancestor worship. The consensus on homesickness between the old overseas Chinese and their descendants is connected by the journey home return. In this regard, overseas Chinese’s activities such as seeking roots, ancestor worship, sightseeing and investment have aroused a new sense of empathy. The familiar Qiaoxiang culture and folk custom become the whole significance of arousing their inner belonging to the carrier. Therefore, from the perspective of folklorism, the integration of fragmentary Qiaoxiang resources is the basis for the inheritance and creation of overseas Chinese culture [21-25].

Conclusion and Reflection

This paper applies the cultural phenomenon and theoretical model centered on the resourcing of Qiaoxiang to the study of the revitalization of traditional culture and the intensification of cross-border social relations. From the central perspective of the transformation from culture to resources, this paper attempts to explore the social development of Qiaoxiang from the multiple perspectives of “local knowledge”, “public position”, “commonality”, “identity”, “reciprocity” and “cultural object” Cultural integration mode. This study argues that it is precisely because of the diversity of cultural mechanism itself and the interaction with economic capital that the cultural self-continuity and bottom-up integration power in regional society are formed, and this study is the study of this integration power mechanism. This paper focuses on the value of cultural resources such as folk customs and cultural heritage in the process of shaping national identity and discusses the bottom-up driving force of social integration from the perspective of the characteristics of multi resource integration in Qiaoxiang. Together with the top-down social integration, it promotes the formation of the multi integrated pattern of the Chinese nation. The theory of “pluralistic and integrated pattern” is a theory put forward by Mr. Fei Xiaotong, one of the most distinguishing anthropologists in China, in his later years to explain the characteristics of the Chinese nation. By following the explanation of this theory at the micro level, we try to construct a theoretical framework to explain the formation of this pattern. In terms of research methods, this study introduces the regional research method based on the in-depth field investigation of traditional anthropology, especially applies this method to the cultural resources, highlighting the multi-cultural attribute of the regional culture of the hometown of overseas Chinese and the integration and symbiosis beyond the regional space, while the traditional research on the revitalization of culture is mostly the research on the traditional folk customs of a place, which will be the focus of this study It is a supplement to the study of regional folk culture [26-28]. From the perspective of folklorism, driven by nostalgia, the connection between a large number of overseas Chinese and the Qiaoxiang in the mainland has gradually developed from simply returning home to seek roots and visit relatives to a new direction of investing and developing philanthropy. Behind the concern for nostalgia is the state’s emphasis on the spiritual civilization of overseas Chinese, which is reflected in the construction of the humanistic environment of Qiaoxiang.

Jiangmen City, as “the first Qiaoxiang in China”, its rich cultural resources, as a unique academic resource, are the source of power to study the cultural forms of overseas Chinese. At the same time, because the study area of Qiaoxiang in this study is just in the junction zone of the land Silk Road and the maritime Silk Road, the study of social integration in this zone can promote the connection of the two silk roads, thus forming a closed economic and cultural circle. This research on the bottom-up social integration mechanism is just the continuation of the practical value of the above social governance and cultural resources diversity. If we look at the modern cultural reproduction and reciprocity caused by the integration of Qiaoxiang resources from the perspective of living state and development, we should pay special attention to how the cultural resources are transformed from the natural state of inheritance to the generation of new culture and order integration and identification with the help of cultural power from the perspective of reflection folklorism.

This paper mainly explores and hopes to help the National Overseas Chinese affairs work. Based on the existing local cultural tradition context and cultural resources of Qiaoxiang, how to guide the cultural resources and capitalization caused by nostalgia consciousness to the power of integration of traditional folk cultural resources of Wuyi Qiaoxiang, including causal power (where is the hometown of overseas Chinese), efficiency power (the goal of cultural resources), conditions or conditions Situational motivation (under what circumstances and in what ways to mobilize the cultural resources in Qiaoxiang), relational motivation (the relationship between the reciprocal development of overseas Chinese and their ancestral land and the national policy environment), variation motivation (the similarities and differences of nostalgia concept, traditional concept and dual identity concept and their reasons), cultural motivation (the result of stimulating the production and integration of cultural resources) The idea power of construction and behavior, interactive power (competition, cooperation, symbiosis) and other aspects will also be the following research train of thought.

Acknowledgement

This project is supported by Research of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Jiangmen City 2020. Authors would like to thank Prof. Le Gao for his financial support through the project “Wuyi University Hong Kong Macao Joint Research and Development Fund: 2019WGALH23”.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bourdieu Pierre, Wacquant LD (2004) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Meng Li and Kang Li Trans. Beijing: Central Compiler Press, Pp. 131-134.

- Gordon Mathews (2000) Global Culture/Individual Identity Searching for Home in the Cultural Supermarket. Routledge, pp 9-18.

- Bourdieu Pierre (1997) The Forms of Capital In: AH Halsey, Hugh Lauder, Philip Brown, Amy Stuart Wells (eds) Education: Culture, Economy and Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 46-58.

- Duan Ying (2017) Qiaoxiang as Method: Regional Ecology, Transnational Mobility and Local Perception. Journal of Overseas Chinese History Studies 1: 1-11.

- Xiong Yanjun, Chen Yong (2018) From “Economic Overseas Chinese Hometown” to “Cultural Overseas Chinese Hometown”: A New Perspective of the Sustainable Development. Journal of Huaqiao University 4: 39-47.

- Hermann Bausinger, Volkskunde (1971) Darmatadt: Carl Habel.

- Eric Hobsnawm, Terence Ranger (1983) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wang Wenjie (2014) Folklorism and its differentiated practice. Folklore Studies 2: 15-28.

- Wang Xiaobing (2016) Chinese Folklore: where to Go from Folklorism. Folklore Studies 3: 15-25+158.

- Zhao Shiyu (2006) Ancestral Memory, Homeland Symbol and Ethnic History-Analysis of the Legend of the Great Sophora tree in Hongdong, Shanxi Province. History Studies 1: 49-64+190-191.

- Zhou Xing (2019) Rural Tourism and Folklorism. Tourism Tribune 34(6): 4-6.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1986) The Forms of Capital. In JG Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Zhang Guoxiong (2014) China’s Qiaoxiang Studies. China Overseas Chinese Publishing House.

- Keith D, Markham Travis Proulx, Matthew J Lindberg (2013) The Psychology of Meaning. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- Svetlana Boym (2001) The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basci Books.

- Guangdong Provincial Archives, Guangzhou Overseas Chinese Research Association (1989) Overseas Chinese and Selected Historical Materials of Overseas Chinese Affairs. Guangdong People’s Publishing House.

- Huang Zhaoji, Liang Rongju, Yang Huibo “Jiangmen Literature and History Materials”. 4(6): 18.

- Joyce, Hunt Lynn, Jacob Margaret (1999) Telling the Truth about History. Trans. Liu Beicheng, Xue Xun. Central Compiler Press. Pp. 198.

- Li Yuru (2017) A Discussion on Contemporary Values on Related Overseas Chinese Culture: A Case Study on Qiaoxiang in Fujian and Guangdong Province. Journal of Overseas Chinese History Studies 1: 38-49.

- Lin Jinzhi, Zhuang Weiji (1989) Selected Materials on the History of Overseas Chinese Investment in Domestic Enterprises in Modern Times. Guangdong People’s Publishing House, pp. 82.

- Lin Jiajin (1999) A study on the Remittance of Overseas Chinese in Modern Guangdong. Guangzhou: Zhongshan University Press, Pp. 108.

- Local Records Compilation Committee of Pengjiang District: Records of Pengjiang district, Jiangmen City (1984-2004). Local records Publishing House.

- Moriyama (2018) Law on the Use of Cultural Resources--The ‘Resourcing’ of ‘Culture’ in Colonial Madagascar. in Iwamoto Michiya: Resources of folk culture: a case study of Japan in the 21st century. Shandong: Shandong University Press. pp. 60-86.

- Mei Weiqing, Zhang Guoxiong (2001) History of Overseas Chinese in Wuyi. Guangzhou: Higher Education Press. Pp. 451-454.

- Marilyn Silverman, PH Gulliver (1999) Approaching the Past: Historical Anthropology Through Irish Case Studies. Trans. Jia Shiheng. Wheat field Publishing Co, Ltd Pp. 68.

- Sylvia Fuller (2003) Creating and Contesting Boundaries: Exploring the Dynamics of Conflict and Classification. Sociological Forum 18(1): 3-30.

- Zhang Guoxiong (2020) Internationality of Overseas Chinese Hometown Culture and International Cooperation in the Study of Overseas Chinese Hometown Culture: A Case Study on Chinese Railway Workers in North America. Journal of H anshan Normal University 41(5): 13-19.

- Zhou Min (1995) Chinatown: A Chinese Community with Deep Social and Economic Potential. Commercial Press, Pp. 52.

-

Tian Yang, Le Gao. The Dynamics of Qiaoxiang Spatial Cultural Resources Integration - Taking Jiangmen City as an Example. Glob J Eng Sci. 7(1): 2021. GJES.MS.ID.000654.

-

Cultural resources, Pace, Folklorism, Cultural memory

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- From Cultural Capital to Hometown Resources

- Qiaoxiang Resources: Jiangmen 33 Market Street and Changdi Historic Street

- Qiaoxiang Resources and Nostalgia of Overseas Chinese

- Qiaoxiang Resources: The Spatial Field of Memory

- Nostalgia and Emotional Belonging

- Conclusion and Reflection

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interests

- References