Research Article

Research Article

Efficient 2nd Order Taylor Series Expansion Model to Integrate Stiff and Non-Linear ODEs: Comparison to Rk45-Type Integrators

Ridha Djebali*

University of Jendouba, ISLAIB, Env. Boulevard, PO Box 340 Beja 9000, Tunisia

Ridha Djebali, University of Jendouba, ISLAIB, Env. Boulevard, PO Box 340 Beja 9000, Tunisia, Email: jbelii_r@hotmail.fr

Received Date: November 12, 2020; Published Date: December 02, 2020

Abstract

A Taylor Series Expansion (TaSE) and three Runge-Kutta RK45 embedded pairs numerical integrators of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) are developed. The TaSE model is designed to solve higher order (>1) ODEs. Validation of TaSE was carried out by help of the RK45 models as well as exact solution for well-chosen stiff test cases. The model implementation and its local and global order of accuracy are investigated.

Keywords and Phrases: Taylor Series Expansion model; RK45 integrators; ODEs; Accuracy; Stiffness; Validation

Introduction

Historically, it first started with Ludwig Prandtl in 1904 [1] when he gave a seminar at the International Congress of Mathematics in Heidelberg, under the title “Uber Flussigkeitsbewegungen bei sehr kleiner Rei bung”. Prandtl took the first steps in a branch of science which turns out to be double-edged; on the one hand for the fact of being branched into several physical areas and on the other hand for the challenges encountered mathematically (existence and uniqueness of the solution) then numerically (solvency, accuracy etc.). Prandtl first initiated the theory of boundary layers problems (BLP) and laid its foundations providing later a great research interest for the several scientific and engineering applications such as the calculation of the drag coefficient of a lifting airfoil or hydrofoil airplane wing, turbine blade [2]. A little bit after, Blasius [3] gave in 1908 his famous non-linear boundary value problem (BVP) which, among others, has been used until today as good test case to the new numerical methods and models of integration of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) used in the following for the resolution of partial differential equations (PDEs).

The investigation of differential equations may be done using the symbolic analytic methods (exact), the geometric methods as well as the numerical methods. Besides, Blasius problem is a BVP, posing mathematical and numerical difficulties to its resolution that should only be numerically. Weyl [4] was the first to prove the existence and uniqueness of the solution of the Blasius problem where an accurate determination of the so-called shear stress f′′(0) annoyed researchers. In fact, the Blasius BVP should be transformed to initial value problem (IVP) to complete the explicit and missing equation to the starting closure of the problem. Blasius gave bounds of the value between 0.3315 and 0.33175 and later the value was determined with sufficient precision as f′′(0) =0.332057336. using, among other algorithms, the shooting method and its well recommended variants for BVPs [5-12] as well as the finite differences and collocation methods. Parallel to the continuous appearence of new schemes and families of numerical methods for solving ODEs [13-16], ubiquitous stiff problems are emerging namely in electronics, solid mechanics, plasma physics, chemical

Foot Notes

2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. 93C10, 93C15, 93C20, 30K05

kinetics, biology etc. The application of known methods exhibits some instabilities and accuracy loss. To overcome problems of stability, accuracy and ODEs stiffness due to the presence of different time scales in the handled problem it is inevitably to develop new high order flexible and accurate integrators. Many attempts are made to extend the notion of differential equations and the range of available methods. The classification of solution methods to ODEs and systems of ODEs may be performed differently based on some criteria and properties, namely explicit embedded and implicit methods (especially for the Runge-Kutta RK method variants), onestep, two-steps or multisteps methods [17-19].

Over the years, many numerical methods as listed above but of different forms, namely Adams-Bash forth, Adams-Moulton or Multistep, are used on the same principle. Because of its high performance at relatively little computation cost, the RK4 finds great use in wide range of applications even originally has been founded as fixed-step integrator. The KR4 integrator idea holds wide range of interest and gained continuous development [20- 23] and application which lead to several improvements such as providing adaptive step size. The latter is a good property that should exert a good integrator over its own time-marching; so that the step size h changes continuously to reduce the computational cost while keeping the total error within given tolerance ε. Each ‘new’ step size is called the optimal step size subject the calculation methods. The integrators using this idea are often called embedded pairs method, such as the RK45 variants: RK-Cash Karp method (RK45-CK), RK-Fehlberg method (RK45-F), RK-Dormand-Prince method (RK45-DP) etc.

However, all numerical methods have their own potential, upsides and downsides when solving various types of ODEs and development of new solution techniques is important. In the present work a Taylor Series Expansion (TaSE designed) model is developed to solve higher order (>1) ODEs and system of ODEsand was compared to three home coded RK45 models as well, namely the RK45-CK, RK45-F and RK45-DP. The models are compared on second and three order ODEs test cases presenting different stiffness scales. The TaSE model is designed to solve higher oders ODEs and system of ODEs and is expected to be at least second order solver since it uses the explicit trapezoidal rule.

Taylor Series Expansion Model: Development and Validation

2nd order B. van der Pol problem

The method is explained by an example. Let’s start with the non-linear second order ODE of Balthasar Van der Pol (1926) circuit. A simple model of the ODE is given as follows:

The initial conditions will be chosen as f(0) = 2 and f′(0) = 0 for the variable η ranging in [0,2] and ζ > 0 is a parameter.

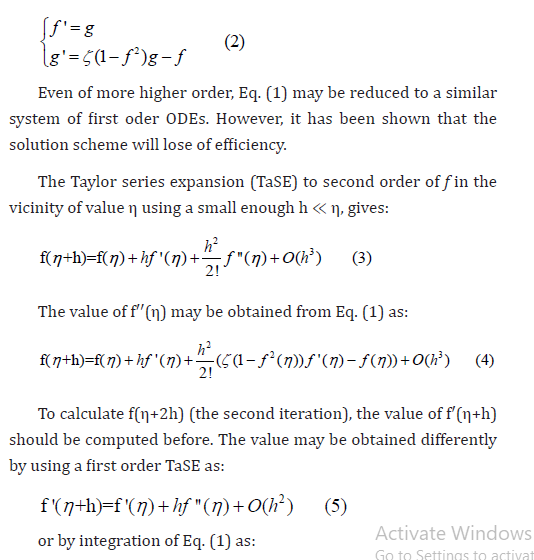

Note that this ODE may be transformed to a system of ODEs as:

One may also calculate f′(η+h) using first order scheme using the increase rate of f or the slope f′′. Note, also, that in the present case the first righ term of Eq. (7) may be integrated directly since the simple form of (1−f2) f′. The needed quantities for the calculation of f (η +h) at Eq. (3) are determined. It is expected to have here a second order accurate solution.

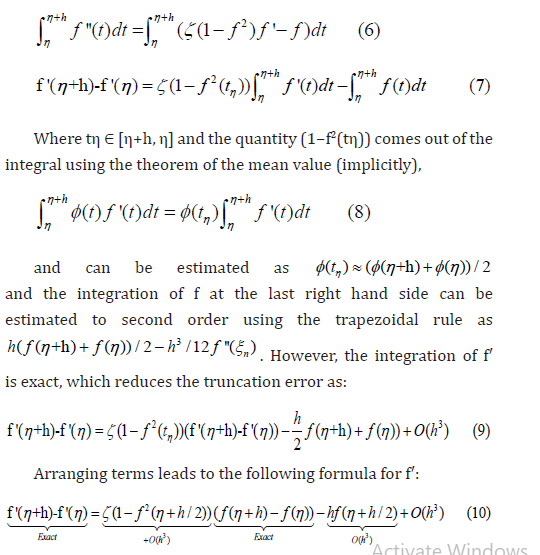

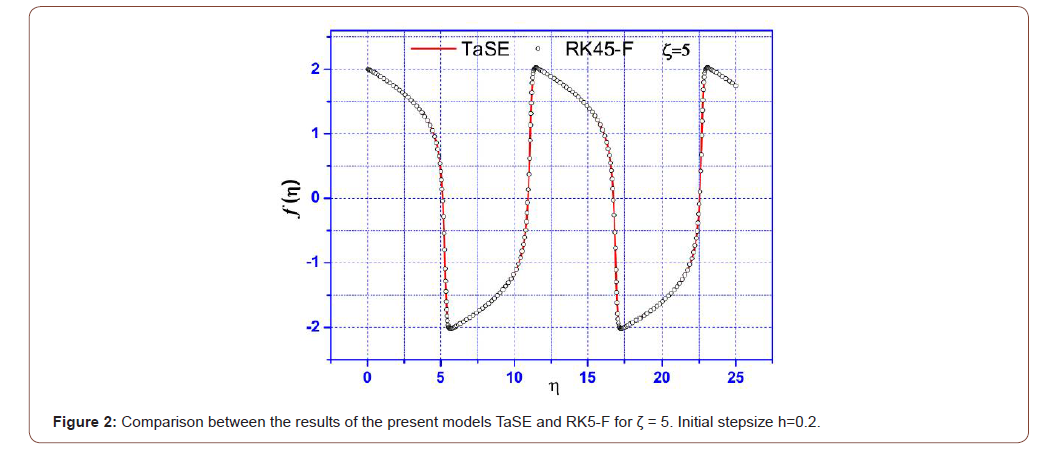

The comparison of the TaSE results against RK45-F and RK45CK ones for the ζ parameter values 0.5 and 5 are plotted in Figures 1 and 2.

The model’s results are in excellent agreement. The comparison case ζ = 5 reveals the problem of flame propagation whose simple model is described by the

The problem is very stiff for very low values of the parameters δ called the initial radius. An investigated method should exhibit sufficient aptitude to simulate the very acute jump of the flame radius. In Figure 2, the two models seem to be efficient to handle such problems.

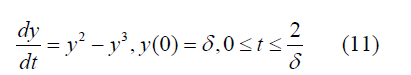

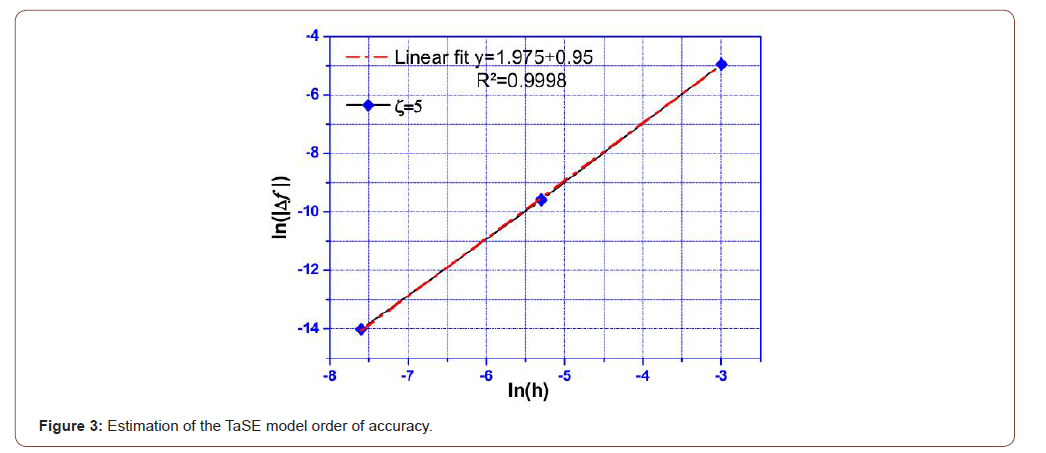

The numerical results of comparison of the TaSE and RK45-F models are given in Table 1. By checking the order of the TaSE model (local error not global) gives that is of second order accuracy. Verification can be performed on the results for the ability to capture a peak, say for example for η = 7 and for different step sizes h = 0.0005, h = 0.005 and h = 0.05. Assuming the truncation error Δf ∼ O(ha) = bha. The plot of ln(Δf) vs. ln(h) is given in

Figure 3. The fit gives ln(Δf) = 1.975 ln(h) + 0.95, so the local deviation under the prescribed conditions (ζ = 5, η = 7) is Δf ≈ 2.4647h1.966. The fit was obtained within R2 = 0.99965 confidence.

Note that the results of Table 1 are obtained for ζ = 5, TaSE model: h = 0.5 10−3, RK45-F and RK45-CK: fixed step h = 10−3 and ε = 10−5 and that the RK45-F integrator is found to be slightly more fast than RK45-CK one regarding the extra number of iterations taken sometimes for adaptive stepsize.

Table 1:Comparison of the present results for three models: TaSE, RK45-F and RK45-CK with relative deviation. The deviation is calculated between TaSE and RK45-F results.

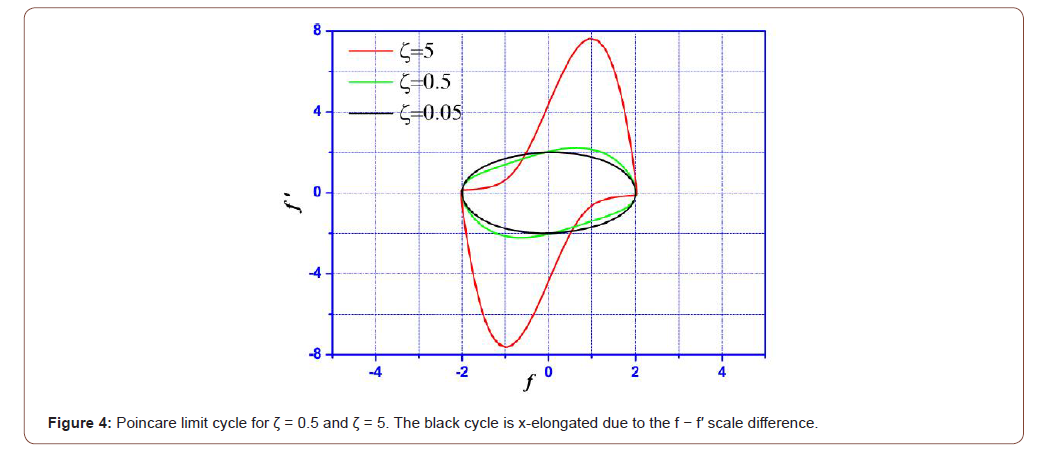

One can observe in the vector field graph (x, x′) of Figure 2, the so-called Poincaré limit cycle which depends strongly on the ζ value. For instance, low ζ values (ζ ≪ 1) lead to circular limit cycle since Eq. (1) becomes equivalent to harmonic equation. The graph solution tends to a circle as shows Figure 4.

The excellent agreement obtained in the first test case shows that the results of the TaSE model exhibit high efficiency in joining integrators of high performance such embedded pairs RK models.

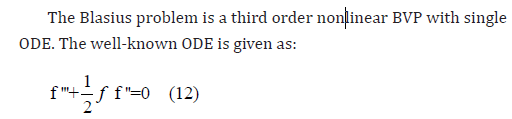

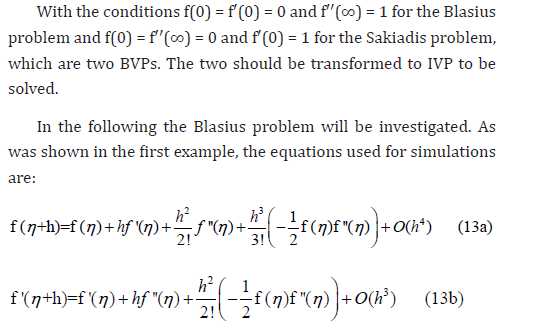

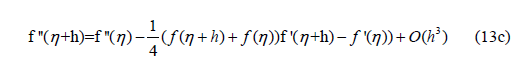

3rd order Blasius and Sakiadis problems

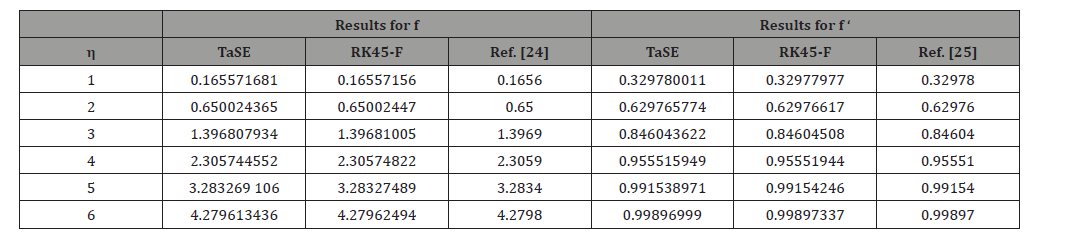

The obtained results for TaSE and RK45-F models gathered with literature results are given in Table 2. The results of the proposed TaSE model are in excellent agreement with those of the RK45-F integrator either for f and f′ even for quite coarse step-size h = 0.01; which reduces considerably the number of iterations. The computed quadratic (RMS) deviation is close to 1.35554E-05 for f and 6.17489E-06 for f′ which supports well on the accuracy of the proposed model.

Table 2:Comparison of the present results for the models TaSE and RK45-F with reference ones for f and f ’. The present results are obtained for h=0.01 for TaSE and h=0.001 for RK45-F.

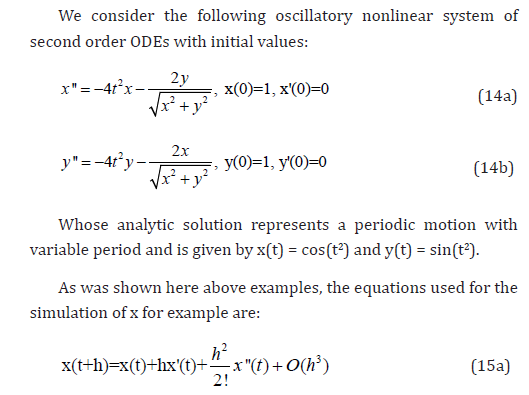

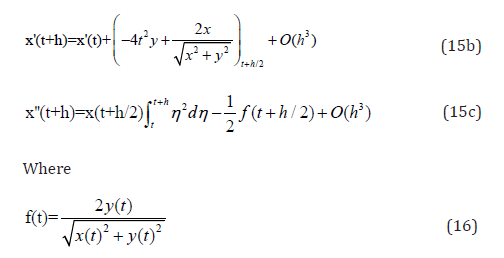

System of coupled 2nd order ODEs

The present example shows how to estimate x′(t + h) to second order in a second order ODE. The problem is solved for t∈[0,7] with step size h = 0.001.

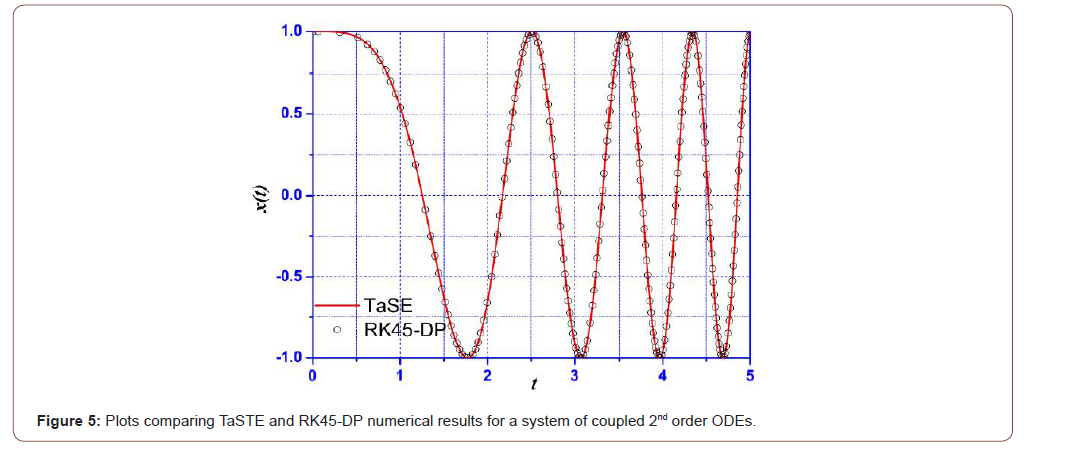

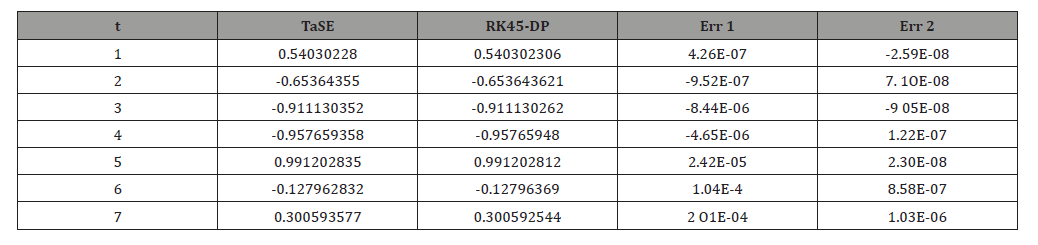

The results of TaSE and RK45-DP models are gathered in Table 3 with their deviations from the exact solution. Extra digits are given here since the comparison is performed against exact solution. The plot of the two computational results is depicted in Figure 5. Results of Table 3 and Figure 5 reveal the powerfulness of the TaSE model. Besides, in this test case we have reviwed the global order of accuracy of the TaSE model. The RMS deviation over the seven computed times was calculated for three stepsizes: h = 0.001, h = 0.005 and h = 0.01. It has been found that ln(Δf) = 1.998 ln(h)+4.445 with a coefficient of determination R2 =1. The expected order of accuracy is always preserved.

Table 3:Comparison of the present results for the models TaSE and RK45-DP with exact solution for a step size h=0.001 for both.

Conclusion

A Taylor Series Expansion numerical integrator of ODEs is developed. The model is exerted to solve higher order ODEs. The following concluding remarks may be drawn:

• The model has been validated on three fourth order accurate RK models and exact solution and gave excellent agreement for three test cases of second and three order ODEs of differents stiffness scales.

• The local and global order of accuracy of the model was checked and estimated to be second order accurate.

• The model is always efficient even for first approximation of the first derivative for second order ODEs.

• The Trapezoidal explicit rule and the theorem of the mean value are used when needed to handle to second order very complex and hard-to-derive terms.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- L Prandtl (1904) Proceedings Third Internernatinal Math. Congress, Engl transl in NACA Tech, pp. 484-494.

- H Blasius (1908) Z Math Phys 56: 1-37.

- L Bairstow (1925) J Roy Aero Soc 29: 3-23.

- H Weyl (1942) Ann Math 43: 381-407.

- T Cebeci, THB Keller (1971) J Comput Phys 7: 289-300.

- A Asaithambi (1997) Appl Math Comput 81: 259-264.

- A Asaithambi (2005) J Comput Appl Math 176: 203-214.

- J Zhang, B Chen (2009) Appl Math Comput 210: 215-222.

- M Ahsan, S Farrukh (2013) Alex Eng J 52: 801-805.

- DD Morrison, JD Riley, JF Zancanaro (1962) Commun ACM 5: 613-614.

- HB Keller (1976) SIAM.

- C Liu (2012) J Optim Theory Appl 152: 468-495.

- Hasim A, Obaid, Rachid Ouifki, Kailash C Patidar (2017) A nonstandard finite difference method for solving a mathematical model of HIV-TB co-infection. Journal of Difference Equations and Applications 23(6): 1105-1132.

- AA Gaber, A Ebaid (2018) Romanian Reports in Physics 70: 110.

- HO Bakodah, A Ebaid, AM Wazwaz (2018) Romanian Reports in Physics 70: 111.

- Pratibhamoy Das (2018) A higher order difference method for singularly perturbed parabolic partial differential equations, Journal of Difference Equations and Applications 24(3): 452-477.

- G Dahlquist (1956) Math Scand 4: 33-53.

- G Dahlquist (1959) Kungl Tekn Hogsk Handl Stockholm 130: 1-87.

- G Dahlquist (1963) BIT 3: 27-43.

- E Fehlberg (1968) NASA TR R-287, NASA.

- K Hussain, F Ismail, N Senu (2015) Mathematical Problems in Engineering, pp. 11.

- H Kasim, I Fudziah, S Norazak (2015) Mathematical Problems in Engineering, pp. 12.

- CV Brian, NA Loppi, PE Vincent (2020) Optimal embedded pair Runge-Kutta schemes for pseudo-time stepping. J Comput Phys 415: 109499.

- L Howarth (1959) Handbuch der Physik 264-350. Springer-Verlag.

- JY Parlange, Braddock RD, Sander G (1981) Acta Mechanica. 38: 119-125.

-

Ridha Djebali. Efficient 2nd Order Taylor Series Expansion Model to Integrate Stiff and Non-Linear ODEs: Comparison to Rk45-Type Integrators. Glob J Eng Sci. 6(5): 2020. GJES.MS.ID.000647.

-

Taylor Serie Expansion model, RK45 integrators, ODEs, Accuracy, Stiffness, Validation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.