Research Article

Research Article

Association of Cytomegalo-Virus and Rubella Virus Infections in Pregnant Women with bad Obstetric History

Raghdah Adel Mohammed Al Qadasi1, Abdullah AD Al Rukeimi3,4, Hassan A Al Shamahy1*, Ahmed Y Al Jaufy1 and Raghad Abdullah Ali Al Rukeimi2

1Department of Medical Microbiology and Clinical Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University, Republic of Yemen

2Department of Obstetrics and gynecology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University, Republic of Yemen

3Department of Obstetrics and gynecology, Saudi Hajjah Hospital, Hajjah city, Yemen

4Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University

Hassan A Al Shamahy, Faculty of Medicine and Heath Sciences, Sana’a University, P.O. Box 775 Sana’a, Yemen.

Received Date: May 13, 2019; Published Date: May 22, 2019

Abstract

Background: Bad obstetric history (BOH) comprises of previous adverse fetal consequences in terms of two or more successive spontaneous abortions, early neonatal deaths, stillbirths, intrauterine fetal deaths, intrauterine growth retardations and congenital anomalies. The infections which are caused by Rubella virus and CMV during pregnancy are often associated with adverse fetus outcomes and reproductive failures. In the Yemen context, the exact seroprevalence of these infections is not known due to unavailability of baseline data.

Objective:The main aim of this study was to determine the correlation of the main viral TORCH infections (Rubella and CMV) during pregnancy among Yemeni females with BOH.

Methods:Two hundred- sixty-eight serum samples were collected from participants having BOH, attending Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Al-Sabian University hospital, Sana’a city during the period of September 2017 to September 2018. IgM antibodies for Rubella virus and CMV were detected by micro-capture ELISA tests.

Results:The common causes of BOH were abortion (52.6%), intrauterine fetal death (22%) followed by intrauterine growth retardation (10.4%). Fourteen (5.2%) of pregnant women were positive for CMV IgM antibodies, 10 (3.7%) for Rubella IgM antibodies and 4 (1.5%) for CMVRubella virus in combination; indicating recent infections. There was significant association between the positive results of anti-CMV IgM -anti- Rubella IgM with age group ≥ 36 years (OR=31,6.2 respectively). Also, there was a significant association between the positive results of anti-CMV IgM with congenital deformation (OR=10.2, p<0.001).

Conclusion: IgM antibody positivity was high for Rubella and CMV and there is a strong association of these agents with BOH. Thus, screening and early diagnosis for these pathogens in women can help in proper management of these cases to prevent fetus loss.

Keywords: TORCH; Bad obstetric history (BOH); CMV; Rubella virus; IgM; Sana’a; Yemen

Introduction

Bad obstetric history (BOH) implies previous unfavorable fetal outcome in terms of two or more consecutive spontaneous abortions, history of intrauterine fetal death, intrauterine growth retardation, stillbirth, early neonatal death, and/or congenital anomalies [1]. The causes of BOH may be genetic, hormonal, abnormal maternal immune response, and maternal infections [2].

The prenatal and perinatal infections, falling under the designation of TORCH complex [3] (also known as STORCH, TORCHES, or the TORCH infections), are a medical acronym for a set of perinatal infections [4], i.e., infections that are passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus. The TORCH infections can lead to severe fetal anomalies or even fetal loss. They are a group of viral, bacterial, and protozoan infections that gain access to the fetal bloodstream trans placentally via the chorionic villi. Hematogenous transmission may occur at any time during gestation or occasionally at the time of delivery via maternal-to-fetal transfusion [5]. Primary infections caused by TORCH-Toxoplasma gondii, Rubella virus, CMV and herpes simplex virus (HSV)-are the major causes of BOH [6]. These infections usually occur before the woman realizes that she is pregnant or seeks medical attention. The primary infection is likely to have a more important effect on fetus than recurrent infection and may cause congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine fetal death, intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, stillbirth, and live born infants with the evidence of disease [7]. Most of the TORCH infections cause mild maternal morbidity but have serious fetal consequences [8]. The ability of the fetus to resist infectious organisms is limited and the fetal immune system is unable to prevent the dissemination of infectious organisms to various tissues [9]. An attempt is being made in this work to find out the correlation of the main viral TORCH infections namely Rubella and Cytomegalovirus during pregnancy among Yemeni females with BOH in Sana’a city, Yemen.

Subjects and Methods

Study design: A cross sectional study.

Study period: September 2017 to September 2018.

Sample size: 268 pregnant women with bad obstetrical history

Selection of cases:

Inclusion criteria: 268 patients having a history of unfavorable fetal outcome in terms of two or more consecutive spontaneous abortion, history of intrauterine fetal death, intrauterine growth retardation, stillbirths, early neonatal death and or congenital anomalies were selected and included in the present study on BOH from pregnant women attending outpatient Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology , Al-Sabian University hospital, Sana’a city-Yemen.

Exclusion criteria” Women with HIV positive, VDRL positive and diabetics were excluded from the study.

Collection of samples

5ml of blood collected aseptically from each woman in a duly labeled plain test tube. Blood could clot for 20 minutes and then serum was separated by centrifugation at 3,000 RPM for 10 minutes and transferred into sterile tubes and stored at -20ºC until the test was performed. Test was performed in the National Center of Public Health Laboratories (NCPHL), Ministry of Health and Population, Sana’a city, Yemen. IgM Anti-Rubella virus and CMV antibodies were detected from serum by micro capture ELISA test kit.

Statistical Analysis

The resulting data were statistically correlated to the ages, gestational stages, and history of BOH in both positive testing and negative-testing pregnant women by calculation associated odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence interval (95%CI). For statistical analysis χ2 and t test were used where appropriate. The differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

Ethical Approval

All women were counseled about the nature of the study and gave their written informed consent. The study proposal was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University.

Results

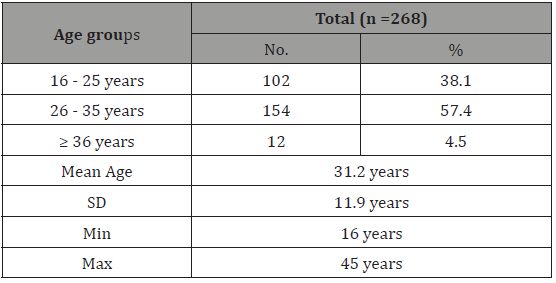

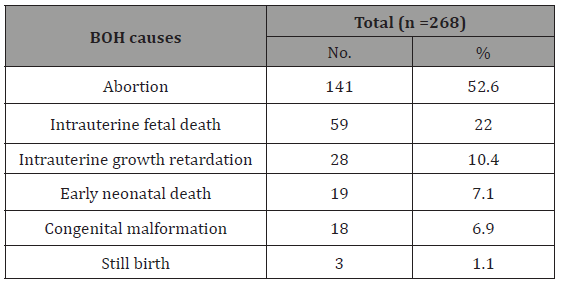

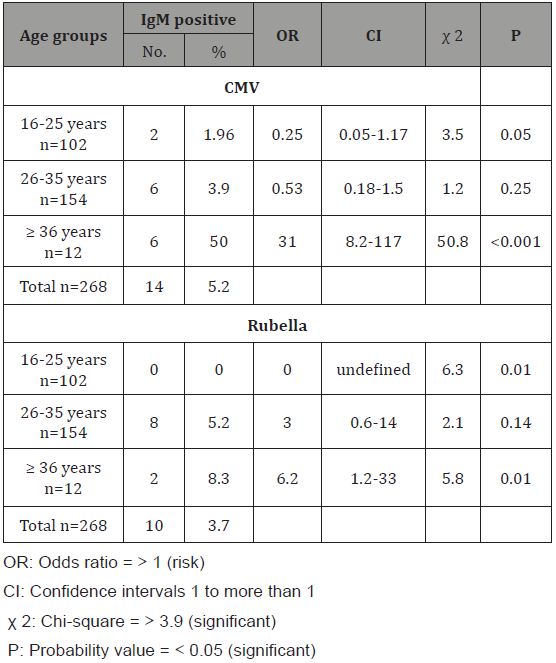

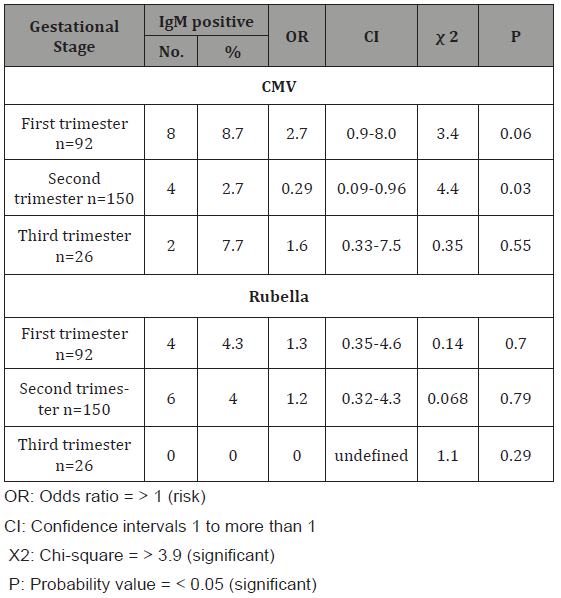

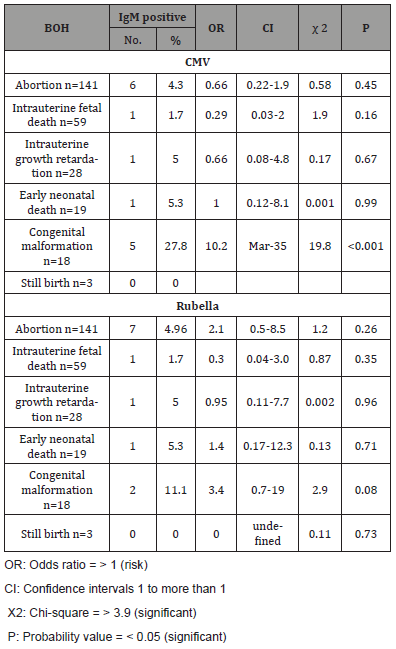

The study was conducted on a total of 268 pregnant women with BOH in Sana’a city during a period of 12 months, starting in September 2017 ending in September 2018. The detailed results of this study are presented in (Tables 1- 5). The tested females ages were ranged from 16 to 45 years old, most of females were in age groups 26 -35 years (57.4 %), followed by 16-25 years (38.1 %), while only 4.5% of the total were in age group ≥ 36 years. The mean age ±SD of them was 31.2±11.9 years. The common causes of BOH in the current study were abortion (52.6%), intrauterine fetal death (22%) followed by intrauterine growth retardation (10.4%) (Table 2). Fourteen (5.2%) of pregnant women were positive for CMV IgM antibodies, 10 (3.7%) for Rubella IgM antibodies and 4 (1.5%) for CMV-Rubella virus in combination; indicating recent infection. There was a statistically significant association between the positive results of anti-CMV IgM with age group ≥ 36 years (OR=31, CI=8.2-117, p<0.001). Also, there was a statistically significant association between the positive results of anti-Rubella IgM with age group ≥ 36 years (OR=6.2, CI=1.2-33, p=0.01) (Table 3). (Table 4) shows the association of positive IgM of CMV and Rubella virus with gestational stages of pregnant women with BOH. There was no a statistically significant association between the positive results of anti-Rubella IgM/ or anti-CMV IgM with the three different gestational stages. Table 5 shows the association of positive IgM of CMV and Rubella virus with history of BOH in pregnant women. There was a statistically significant association between the positive results of anti-CMV IgM with congenital deformation (OR=10.2, CI=3-35, p<0.001).

Table 1: The age distribution of the pregnant women with BOH whom tested for IgM CMV and Rubella virus.

Table 2: The distribution of BOH causes among the pregnant women whom tested for IgM CMV and Rubella virus

Table 3: The association of positive IgM of CMV and Rubella virus with different age groups of pregnant women with BOH.

Table 4: The association of positive IgM of CMV and Rubella virus with gestational stages of pregnant women with BOH.

Table 5: The association of positive IgM of CMV and Rubella virus with history of BOH in pregnant women.

Discussion

Death of an infant in uterus or at birth has always been a devastating experience for the mother and of concern in clinical practice. Perinatal mortality remains a challenge in the care of pregnant women worldwide, particularly for those who had history of adverse outcome in previous pregnancies. To assess the CMV and Rubella infections during pregnancy among women with BOH women this study was undertaken.

In the current study the most common BOH cause was abortion (52.6%). Our results are like overall incidence of BOH in literature in which abortion is the common cause [10,12]. This result can be explained by fact that two early miscarriages are experienced by so many women that it should be considered a normal phenomenon that is most likely caused by de-novo fetal chromosome abnormalities occurring twice by chance. Fifty percent of cultivable tissue samples from miscarriages occurring sporadically have chromosome abnormalities [10,12]. Additionally, abortion is an issue in pregnancy wastage with its concomitant social and economic impacts. Among several other causes of fetal loss in human reproduction, TORCH (like Cytomegalovirus and Rubella) agents are often responsible for abortion and the rate of spontaneous abortion from fetal infection ranges from 10-15%. Primary infection during pregnancy may cause spontaneous abortion or stillbirth [13] and prevalence of infections as CMV and Rubella virus being high in the developing countries as Yemen [14,15]. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies concerning anti-CMV IgM and/or anti-Rubella virus IgM prevalence among women with BHO in Yemen, but there are many studies concerning prevalence of CMV or Rubella virus among females in general or in pregnant women [16,17]. So, this study was the first study determined the correlation of Rubella and Cytomegalovirus during pregnancy among Yemeni females with BOH.

In the present study, the prevalence of anti-CMV IgM and anti-Rubella virus IgM among BHO women was 5.2% and 3.7% respectively. These results are roughly like those reported in Egypt 4.1% for anti-CMV IgM and 2.5% for anti-Rubella virus IgM [18], and in Iran 4.5% for anti-CMV IgM and 4.8% for anti-Rubella virus IgM [19]. But our results are slightly higher than that in Turkey 1.5% for anti-CMV IgM and 1.2% for anti-Rubella virus IgM [20]. Also, our results were lower than that reported in studies, in Iraq (22% for anti-CMV IgM and 16.6% for anti-Rubella virus IgM) [21], and in India (12.6% for anti-CMV IgM and 14.2% for anti-Rubella virus IgM) [22]. The variation in the rates of active CMV and Rubella virus infections in the different parts of the world it can be due to the rate of exposure [23], methods of diagnosis, the social variations such as population behavior, hygienic habits, cultural differences related to feeding habits, educational levels, primary health care program, early diagnosis of infections and local infection control policy as vaccination [24]. In our study co-infections of CMV and Rubella virus was found in four (1.4%) of our female with BOH which is like that reported from India where the rate of co-infection was 1% [25], but lower than that reported from Iraq (5%) [26].

In the current study, there was significant association between older age groups and trend of CMV and rubella infections. These results agreed with that reported from India [22] but disagree with that reported from Egypt [18], Nigeria [27] and Iran [28] in which no correlation between age determinant and CMV and/or Rubella infections among females with BOH.

The present study also observed that there was no statistically significant association between anti-CMV and rubella IgM and gestational stages (p>0.05) (Table 4). However, a low positive rate (2.7%) for CMV IgM was found in women in the second trimester with unassociated risk factor of contracting HCMV infection equal to 0.29 (p=0.03). On other hand a higher rate of active CMV infection was found in the first trimester. A similar observation was reported from Iraq [29], and Iran [28]. Besides, the higher positive rate of Rubella virus IgM was found in the first trimester (4%) (Table 4), no positive Rubella virus IgM was recorded in the third trimester in the current study. A similar observation was reported in Tanzania [30], but disagreement with that reported from Sudan [31]. These results might be explained by that, the first trimester of pregnancy is an important period associated with several complications such as bleeding and inflammation of the uterus which lead to maternal infections by pathogenic organisms mostly belonging to the TORCH agents. In this study, a statistically significant association between anti-CMV IgM and congenital deformation with rate equal to 27.8% and associated OR equal to 10.2 times (CI=3- 35, p<0.001) (Table 5). However, we observed non-statistically significant association between anti-Rubella virus IgM and congenital deformation (OR=3.4, p=0.08) (Table 5). Our findings disagreed with that reported in Iraq for anti-CMV IgM and agreed with anti- Rubella virus IgM [32]. Lack of association between anti-Rubella virus IgM and congenital deformation in both studies could be due to that malformations arise during embryogenesis and fetal development as a result of some environmental factors and genetic mutations.

Finally, women affected with any one of these diseases during pregnancy are at high risk for miscarriage, stillbirth, or for a child with serious birth defects. Thus, there is need of performing the TORCH test as early as possible for diagnosing and determining the mother’s exposure to Rubella virus and Cytomegalovirus infection.

Conclusion

In conclusion this study has established that CMV and Rubella infection play an important role in adverse fetal outcome in pregnant women. In order to prevent the morbidity and mortality of fetus all antenatal cases with bad obstetrical history even if not having any symptoms should be screened for TORCH agents as early as possible for early diagnosis and appropriate management.

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge the financial support of Sana’a University and the Microbiology Department of the National Center of Public Health Laboratories (NCPHL) Sana’a, Yemen which provided working space.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest associated with this work.

References

- Kumari N, Morris N, Dutta R (2011) Is screening of TORCH worthwhile in women with bad obstetric history: an observation from eastern Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr 29(1): 77-80.

- Turbadkar D, Mathur M, Rele M (2003) Seroprevalence of TORCH infection in bad obstetric history. Indian J Med Microbiol 21(2): 108-110.

- Nickerson JP, Richner B, Santy K, Lequin MH, Poretti A, et al. (2012) Neuroimaging of pediatric intracranial infection--Part 2: TORCH, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections. J Neuroimaging 22(2): e52-e63.

- Maldonado YA, Nizet V, Klein JO, Remington JS, Wilson CB (2011) Current concepts of infections of the fetus and newborn infant. In Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant (7th Edn), Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado YA (edts), Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, USA, pp. 1-23.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J, (2009) Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th Edn) Philadelphia PA: Elsevier, USA, p. 480.

- McCabe R, Remington JS (1988) Toxoplasmosis: the time has come. N Engl J Med 318(5): 313-315.

- Maruyama Y, Sameshima H, Kamitomo M, Ibara S, Kaneko M, et al. (2007) Fetal manifestations and poor outcomes of congenital cytomegalovirus infections: possible candidates for intrauterine antiviral treatments. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 33(5): 619-623.

- Stegmann BJ, Carey JC (2002). TORCH infections. Toxoplasmosis, other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), Rubella, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Herpes infections. Curr Womens Health Rep 2(4): 253-258.

- Mladina N, Mehikic G, Pasic A (2000) [Torch infections in mothers as a cause of neonatal morbidity]. Med Arh 54(5-6): 273-276.

- G Singh, K Sidhu (2010) Bad Obstetric History: A Prospective Study. Med J Armed Forces India 66(2): 117-120.

- Pfeiffer KA, Fimmers R, Engels G, van der Ven H, ven der Ven K (2001) The HLA-G genotype is potentially associated with idiopathic recurrent spontaneous abortion. Mol Hum Reprod 7(4): 373-378.

- Kruse C, Rosgaard A, Steffenson R, Varmint K, Jensenius JC, et al. (2002) Low serum level of mannan-binding lection is a determinant for pregnancy outcome in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187(5): 1313-1320.

- Sharareh Ariani, Leila Modiri Arash Chaichi (2014) Study on the IgG and IgM antibodies rate of virus HSV, CMV and rubella in the women with recurrent pregnancy loss history. Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences 4(3): 212-222.

- Freeman RB Jr (2009) The ‘indirect’ effects of cytomegalovirus infection. Am J Transplant 9(11): 2453-2458.

- Marshall BC, Koch WC (2009) Antivirals for cytomegalovirus infection in neonates and infants: focus on pharmacokinetics, formulations, dosing, and adverse events. Paediatr Drugs 11(5): 309-321.

- Saeed MS Alghalibi, Qais YM Abdullah, Saad Al-Arnoot, Assem Al- Thobhani (2016) Seroprevalence of Cytomegalovirus among Pregnant Women in Hodeidah city, Yemen. Journal of Human Virology & Retrovirology 3(5): 00106.

- Rabbad A, Al-Shamahy H (2002) Seroprevalence of rubella antibodies among a selected sample of women of childbearing age in Sana’a, Journal of the Arab Board of Medical Specializations.

- Noha S Ahmed, Heba A Ahmed, Nesreen A Mohammed, Hameda H Mohamed (2018) Toxoplasma, Cytomegalovirus and Rubella Infections among Aborted Women Attending Sohag University Hospital, Egypt. Parity, Egypt, Egyptian Journal of Medical Microbiology 27(1): 89-94.

- Golalipour MJ, Khodabakhshi B, Ghaemi E (2009) Possible role of TORCH agents in congenital malformations in Gorgan, northern Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J 15(2): 330-336

- Sirin MC, Agus N, Yilmaz N, Bayram A, Derici YK, et al. (2017) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii, Rubella virus and Cytomegalovirus among pregnant women and the importance of avidity assays. Saudi Med J 38(7): 727-732.

- Amer Ali Hammadi, Hameedah Hadi Abdul Wahed, Aseel Najah Sabour (2017) Study Causes of Repeated Abortion In Pregnant Women In Karbala City. Scientific Journal of Medical Research 1(3): 96-98.

- Sana Tiwari, Balvinder Singh Arora, Rupali Diwan (2016) TORCH IgM seroprevalence in women with abortions as adverse reproductive outcome in current pregnancy. International Journal of Research in Medical Science 4(3): 784-788.

- Bukbuk DN, el Nafaty AU, Obed JY (2002) Prevalence of rubella-specific IgG antibody in non-immunized pregnant women in Maiduguri, north eastern Nigeria. Cent Eur J Public Health 10(1-2): 21-23.

- Correa CB, Kourí V, Verdasquera D, Martinez PA, Alvarez A, et al. (2010) HCMV seroprevalence and associated risk factors in pregnant women, Havana City, 2007 to 2008. Prenat Diagn 30(9): 888-892.

- Jay Parikh, Anil Chaudhary, GU Kavathia, YS Goswami (2016) Prevalence of Serum Antibodies to Torch Infection in Women with Bad Obstetric History Attending Tertiary Care Hospital, Gujrat. Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences 15(5): 14-16.

- Nuha Jaboory Hadi (2011) Prevalence of Antibodies to Cytomegalovirus, Rubella Virus and Toxoplasma gondii among aborted women in Thiqar province. Journal of College of Education for Pure Science 1(5): 3-9.

- Ogbaini-Emovon E, Oduyebo OO, Lofor PV, Onakewhor JU, Elikwu CJ (2013) Seroprevalence and risk factors for cytomegalovirus infection among pregnant women in southern Nigeria. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 3(03): 1-3.

- Jomehzadeh N, Shahi F, Kooti S, Gorjian Z, Lorestani HA, et al. (2017) Frequency and Comparison of Women with Natural Chil Beheshti Hos. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 9(3): 1748-1757.

- Al-Saeed AT, Abdulmalek IY, Ismail HG (2015) Study of Torch Outcome on Pregnancy and Fetus in Women with Bod in Duhok Province–Kurdistan Region– Iraq. Science Journal of University of Zakho 3(2): 171-182.

- Lukombodzo Lulandala, Mariam M Mirambo, Dismas Matovelo, Balthazar Gumodoka, Stephen E Mshana (2017) Acute Rubella Virus Infection among Women with Spontaneous Abortion in Mwanza City, Tanzania. J Clin Diagn Res 11(3): QC25-QC27.

- Elamin MH, Al-Olayan EM, Omer SA, Alagaili AN, Mohammed OB (2012) Molecular detection and prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in pregnant women in Sudan. African journal of microbiology research 6(2): 308- 311.

- Esraa Abdul Kareem Mohammad, Yahya Jirjees Salman (2014) Study of TORCH infections in women with Bad Obstetric History (BOH) in Kirkuk city. International Journal Current Microbiology Applied Science 3(10): 700-709.

-

Abdullah AD Al Rukeimi, Hassan A Al Shamahy, et al. Association of Cytomegalo-Virus and Rubella Virus Infections in Pregnant Women with bad Obstetric History Association of Cytomegalo-Virus and Rubella Virus Infections in Pregnant Women with bad Obstetric History. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2(3): 2019 WJGWH.MS.ID.000538.

TORCH, Bad obstetric history (BOH), CMV, Rubella virus, IgM, Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Fetus, Retardation, Prematurity, Infants

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.