Case Report

Case Report

A Case Report of Severe Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy with Severe Liver Damage as the Main Manifestation

Guolin He1,2, Xibiao Jia1,2, Ran Cheng1,2, Jinfeng Xu1,2, Yu Xuan1,2 and Bing Peng1,2*

1West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, China

2Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children (Sichuan University), Ministry of Education, China

Bing Peng, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610000, China and Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children (Sichuan University), Ministry of Education, China.

Received Date:June 25, 2021; Published Date: July 13, 2021

Summary

Background: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is the most common liver disorder during pregnancy. Most ICP cases have good prognosis after delivery. The mother’s ICP symptoms and biochemical abnormalities usually resolve after delivery.

Case: This was a severe ICP with severe liver damage as the main manifestation. One week after childbirth, her liver damage did not gradually recover but gradually worsened. This case showed quite difference from the common ICP cases. We have not found similar case reports.

Conclusion: The particularity of the onset and outcome of this case, compared with the conventional ICP case, which gives us a new perspective on ICP.

Keywords: ICP; Pregnancy; Prognosis; Bile acids; Liver transaminases aspartate aminotransferase; Liver alanine aminotransferase

Abbreviations: ICP: Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy; AST: transaminases aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; GDM: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; D1L1: Drug-induced Liver Injury; AIH: Autoimmune Hepatitis; AFLP: Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is the most common liver disorder during pregnancy [1]. Among these patients, bile cannot flow from the liver. The frequency of ICP varies widely between 0.1% and 25% with the specificity of ethnicity and geographic location. More cases about 0.8-1.46% were discovered in South Asian. The greatest prevalence was discovered in South American populations with up to 25% in women of Araucanian Indian. In China, the incidence has been reported be 0.8%-12%. ICP often appears in the late second or third trimester of pregnancy. It is a reversible form of cholestasis and tends to dissolve quickly after birth. Its characters involve pruritus, elevated serum bile acid levels, and abnormal liver function. It has been associated with sudden fetal death and fetal distress, stillbirth, and respiratory distress syndrome of newborn [1].

The diagnosis of ICP involves a rise in serum bile acids and transaminases. in ICP, the liver transaminases aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are commonly elevated, and the elevation may precede the increase in bile acids by 1 to 2 weeks. ALT is more sensitive than AST and may increase 2- to 10-fold in most cases. The primary treatment used for ICP is Ursodeoxycholic acid [2]. Itching often resolve within 48 hours and biochemical abnormalities often recover within 2–8 weeks in most cases [1]. We report here a case with severe liver damage as the main clinical manifestation. The liver function was unexpectedly severely damaged and progressively worsened after delivery, which has puzzled us from diagnosis to treatment.

Case Presentation

Our patient was 36-year woman who first presented to the clinic with a history of two gravidas and one early spontaneous abortion. The gestational age was 38 weeks and 2 days, which was from reliable last normal menstrual period. She receipted regular antenatal care follow up at West China Second University Hospital. She presented to prenatal care clinic with a chief compliant of mild whole-body skin itching, especially around the belly button for one day. She denied history of nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain and urinary symptoms. She was diagnosed as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in 24 weeks of gestation. Necessary dietary and exercise recommendations were given accordingly. The patient’s blood glucose stayed within the required range since. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism for more than 4 years and had been taking orally 50ug Euthyrox (Levothyroxine Sodium Tablets) per day. Additionally, she had been taking multivitamins (containing 800ug of folic acid) and calcium from the beginning of pregnancy. She had no history of hypertension or hepatitis and constitutional hyperbilirubinemia. Her routine biochemical test one month ago was normal. Physical examination did not reveal abnormal skin and conjunctiva with jaundice. Nausea, vomiting, headache, abdominal pain or fatigue were absent. Blood pressure and vital signs were normal.

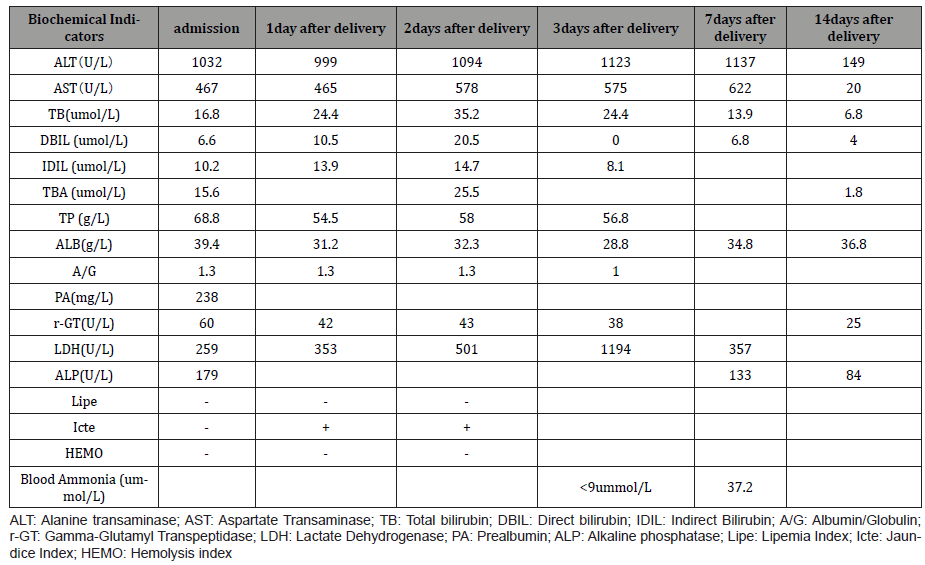

Laboratory tests revealed that the direct bilirubin (D-Bil 6.6umol/ml), AST (467 IU/l), ALT (1032 IU/l), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, 241 IU/l) were all elevated. Total bile acid level was slightly elevated (15.6 μmol/l) at the time of admission (Table 1). No hemolysis or thrombocytopenia was noted. Viral markers tests of hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Tests of autoimmune markers including anti-nuclear, anti-mitochondrial, and anti-phospholipid antibodies were negative. The result of Thyroid function was normal. On the basis of these results, she was diagnosed as pregnancy with severe liver function impairment. However, the cause of the severe liver damage was unclear.

Table 1: Results of laboratory investigation.

Considering that her gestational age was beyond 38 weeks, and that her liver was severely damaged. We decided to perform cesarean section after consultation with the patient and her family. The operation was performed smoothly. The amniotic fluid was clear and slightly yellowish green. The newborn was male, with a birth weight of 2900g and an Apgar score of 10-10-10.

After surgery, the mother had stable vital signs, without anorexia grease or nausea. Her skin and conjunctiva color were normal. The examination on the first day after delivery showed that the liver damage was still severe (Table 1). Kidney function tests were normal. Urine analysis revealed normal color, a pH of 0.5, all negative urine protein, urine biliary element, and bilirubin. The coagulation function test was normal. The symptoms of itchy skin gradually disappeared. After one week of treatment, her liver function deterioration progressively. The patient was transferred to the department of gastroenterology. She was given polyene phosphatidylcholine 930 mg intravenously every day, and 200 mg magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate injection every 12 hours. She underwent further examination. The tests of AMA (antimitochondrial M2 antibody), LKM (anti-liver and kidney particle antibody), LC-1 (anti-hepatic cytosolic antibody), SLA (anti-soluble hepatogen antibody) were negative. The screen of EB virus DNA, hepatitis markers (hepatitis A, B, and C), and TORCH were all negative. The reports of autoimmune antibodies (ELISA) were negative, that included Nrnp/Sm, Smith, SS-A(Ro), SS-B(La), Scl-70, Jo-1, Ro-52, CENPB, PCNA, PM-Scl, NU, MA, HI, dsDNA, RIB, ANA. Tests of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, and IgM were all negative. Complement level were increased, as following: C3 1.74g/L, C4 0.27g/L, IgE 81.10IU/ml.

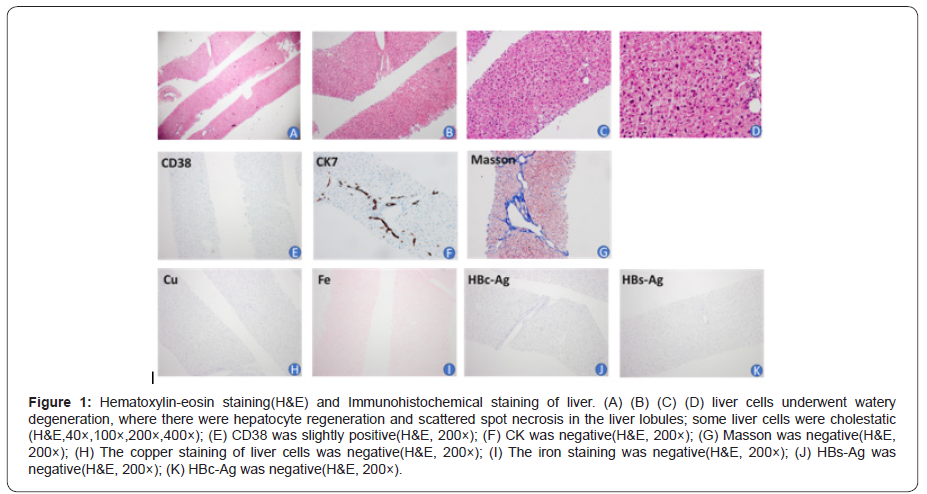

Her liver fiber ultrasound showed that SWE liver stiffness value was 4.6kpa. Her liver biopsy showed that the liver cells underwent watery degeneration, where there were hepatocyte regeneration and scattered spot necrosis in the liver lobules; some liver cells were cholestatic. Immunohistochemistry showed that HBs-Ag and HBc-Ag were negative, IgG4 was negative, a small number of CD38 were found. The copper and iron staining, PAS and D-PAS of liver cells were all normal (Figure 1). The result was that the patient had mild chronic liver inflammation (G1S1), combined with lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration (+1), and bile duct changes (-3), so the patient might be suffering from drug-induced liver injury (D1L1), or autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). In addition, based on the patient’s medical history, the pathologist wondered that she might have suffered from intrahepatic cholestasis during pregnancy.

After 2 weeks of treatment, the patient’s liver function indicators gradually returned to normal and she could discharge. Her liver function was checked again one week after discharge and 42 days after delivery, and the results were normal.

Discussion

Common causes of abnormal liver function during pregnancy include hyperemesis gravidarum, ICP, hypertension in pregnancy, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, autoimmune diseases, viruses, and drug-induced liver toxicity [3]. In this case, the history and clinical evidence of hyperemesis gravidarum and gestational hypertension were lacking. The patient’s autoimmune antibody and virus tests were all negative. Therefore, it is unlikely that the patient’s abnormal liver function was due to autoimmune process or viral infection. About a half of patients suffering drug-induced liver damage may develop cholestasis. Yonghong Zhang, et al. [4] analyzed 9.5 million FDA drug adverse reactions, looking for drugs that may cause cholestasis. They found that an increased risk of cholestasis was associated with lansoprazole, omeprazole, and amoxicillin. The oral medications for this patient during pregnancy were vitamins, calcium and Euthyrox. These drugs have little effect on liver function, and there is no report on these drugs causing severe damage of liver function.

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a unique disease in the third trimester. It is a common cause of vesicular fatty infiltration of liver cells and liver failure. The incidence rate is 1/7,000 to 1/15,000. It often occurs at 28-40 weeks of pregnancy. In the biochemical examination of acute fatty liver of pregnancy, serum transaminase, serum uric acid and bilirubin are elevated, and blood clotting time is prolonged. Other typically associated abnormalities include leukocytosis, anemia, hypoproteinemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulation dysfunction, and renal dysfunction. Obviously, except for the elevated level of AST and ALT, her renal function and blood coagulation were normal. There was not sufficient evidence for the diagnosis of AFLP for this patient. Based on all the patient’s test results and her outcome, we wondered that her diagnosis of ICP was the most appropriate.

Internationally, the uniformed diagnostic criteria for ICP have been lack. Most guidelines approve the demands of pruritis and abnormal liver function. The diagnosis of ICP is mainly based on the clinical symptoms. Common laboratory indicators include elevated bilirubin levels, generally not exceeding 6 mg/dL, and transaminase levels rising from the lowest level to 20 times the normal value. The most sensitive laboratory indicator is serum bile acid, and it is the only laboratory abnormality that can be used as a diagnostic criterion. In general, patients with ICP have bile acid> 10 μmol/L, which can be as high as 100 times the normal value, and usually returns to normal 2-8 weeks after delivery.

The etiology of ICP involves many factors including hormonal balance, genetic components and environmental factors. The variation in genetics leads to the different prevalence rates in different ethnic groups [5]. However, to date, the pathogenesis of ICP is still not clear. In recent years, it has been increasingly recognized that the occurrence of ICP is related to metabolic abnormalities, including glucose intolerance and dyslipidemia [6]. A study reported that 19% of ICP patients had GDM, and 13.6% of GDM patients had ICP [7]. Follow-up studies confirmed this result, and the association was stronger. This patient was associated with gestational diabetes and was a high-risk group for ICP.

The clinical condition of ICP patients is generally mild, and most patients only have low-to-moderate abnormalities of liver function. In addition to severe itching, most patients generally do not have serious or long-term complications. In some patients with ICP, transaminase was increased before TBA was increased. ALT and AST were slightly elevated in more than 60% of the patients, generally twice to ten times the normal ranges [8]. In this case, the patient had extremely severe liver failure, and her transaminase was more than 30 times higher than normal ranges, which was extremely rare. One other aspect of the patient’s situation that confused us was that her total bile acid was only slightly elevated, which did not seem to match the high transaminase level. Therefore, it was difficult to reach the diagnosis of ICP when she was first admitted. We had been looking for evidence of such severe liver damage, but no other evidence had been found. 7 days after delivery, the patient’s transaminase did not improve. However, in most cases, the liver function and itching symptoms of ICP patients can be relieved quickly after delivery. Because of the patient’s extremely elevated ALT and AST, she got a liver biopsy to further clarify the cause of liver damage. Normally, patients with ICP do not need liver biopsy. It should only be performed if pruritus-free jaundice occurs before 20 weeks of pregnancy and abnormal laboratory test results continue to occur after 8 weeks of delivery. Even if a liver biopsy is performed in patients with ICP, the liver biopsy will indicate cholestasis with minimal or no inflammatory changes. Her pathological result of liver biopsy was suspected to be diagnosed as ICP. According to all the results, we had to continue to treat her with the ICP treatment principles. Fortunately, after one more week, the patient’s liver function gradually returned to normal.

Conclusion

ICP is a relatively popular hepatic disorder in pregnancy. The prominent contradiction in this case we reported was the rare elevated transaminase, which was also the reason for the difficult diagnosis. The second important point was that the patient’s condition did not relieve but worsened one week after delivery, which was very different from the condition of most ICP patients. The particularity of the onset and outcome of this case, compared with the conventional ICP case, which gives us a new perspective on ICP.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the pregnant woman and midwifes involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declare that they do not have any conflict.

References

- Nilsson CG, HaukkamaaM, VierolaH, Luukkainen T (1983) Tissue concentrations of levonorgestrel in women using a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Clin Endocrinol 17(6): 529-536.

- Bednarek PH, Jensen JT (2009) Safety, efficacy and patient acceptability of the contraceptive and non-contraceptive uses of the LNG-IUS. Int J Womens Health 1:45-58.

- M Yang, H Xu, N Chu, Cao L, Gui Y, et al. (2013) Bioequivalence of compound levonorgestrel tablets in healthy volunteers. Pharmaceutical Care & Research 13(2): 133-135.

- Rutanen EM (1998) Endometrial response to intrauterine release of levonorgestrel. Gynecol Forum 3(1): 11-14.

- Qi Jie, Fan Limei, Lu Xue (2015) Basic research on Levonorgestrel-releasing Intrauterine system. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 30(21): 3751-3754.

- Shan D, Jinghe L (2004) The clinical function and related basic research of Levonorgestrel-releasing Intrauterine system.Foreign Medical Sciences(Obstet Gynecol Fascicle) 31(5): 285-288.

- Gardner FJ, Konje JC, Abrams KR, Brown LJ, Khanna S, et al. (2000) Endometrial protection from tamoxifen-stimulated changes by a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: a randomised controlled trail. Lancet 356(9243): 1711-1717.

- Luukkainen T,Lähteenmäki P, Toivonen J (1990) Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Ann med 22(2): 85-90.

- Xiao B, Zeng T, Wu S, Sun H, Xiao N (1995) Effect of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device on hormonal profile and menstrual pattern after long-term use. Contraception 51(6):359-365.

- Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E (1995) Ovarian function after seven years' use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept 11(2):85-95.

- Pakarinen PI, Lähteenmäki P, Lehtonen E, Reima I (1998) The ultrastructure of human endometrium is altered by administration of intrauterine levonorgestrel. Hum Reprod 13(7): 1846-1853.

- Luukkainen T, Pakarinen P, Toivonen J (2001) Progestin-releasing intrauterine system. Semi Reprod Med 19(4): 355-363.

- Huang He, Tian Qinjie (2016) The clinical application of Levonorgestrel-releasing Intrauterine system in gynecological diseases. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 25(6): 580-584.

- Tian Qinjie, Wang Chunqing (2014) Application progress of Levonorgestrel-releasing Intrauterine system in abnormal uterine bleeding. Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 49(7): 553-555.

- Xiaoyan Z, Weiyang Z, Huifang M (2016) Application progress of Mirena in endometrial precancerous lesions. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 31(7): 1568-1570.

- Gallos ID, Shehmar M, Thangaratinam S, Papapostolou TK, Coomarasamy A, et al. (2010) Oralprogestogens vs levonorgestrel- releasing intrauterine system forendometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203(6): 1-10.

- Zhang P,Song K,Li L, Yukuwa K, Kong B (2013) Efficacy of combined levonorgestrel- releasing intrauterine system with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for the treatment of adenomyosis. Med Princ Pract 22(5):480-483.

- Abu Hashim H, Zayed A, Ghayaty E, Rakhawy ME (2013) LNG-IUS treatment of non- atypical endometrial hyperplasia in perimenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. J Gynecol Oncol 24(2): 128-134.

- Bahamondes L, Valeria Bahamondes M, Shulman LP (2015) Noncontraceptive benefits of hormonal and intrauterine reversible contraceptive methods. Hum Reprod Update 21(5): 640-651.

- Shi Q, Li J, Li M, Wu J, Yao Q, et al. (2014) The role of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer taking tamoxifen. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 35(5): 492-498.

- Fu Y, Zhuang Z (2014) Long-term effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7(10): 6419-6429.

- El Behery MM, Saleh HS, Ibrahiem MA, Kamal EM, Kassem GA, et al. (2015) Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus dydrogesterone for management of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. Reprod Sci 22(3): 329-334.

- Kim MK, Seong SJ, Kim JW, Jeon S, Choi HS, et al. (2016) Management of Endometrial Hyperplasia with a Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System: A Korean Gynecologic-Oncology Group Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 26(4): 711-715.

- Soini T, Hurskainen R, Grénman S (2016) Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and the risk of breast cancer: A nationwide cohort study.Acta Oncol 55(2): 188-192.

- (2016) Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecological Endoscopy (BSGE). Management of endometrial hyperplasia green-top guideline 67 RCOG/BSGE joint guideline. London:

- (2017) Reproductive Endocrinology Group of the Women and Children Health Industry Branch of the National Health Industry Enterprise Management Association. Consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of endometrial hyperplasia in China. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 26(10): 957-959.

- (2009) Endocrinology Group, Chinese Medical Association Obstetrics and Gynecology Branch. Guidelines for clinical diagnosis and treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 44(3): 234-236.

- (2014) Gynecological Endocrinology Group, Chinese Medical Association Obstetrics and Gynecology Branch. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding. Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 49(11): 801-806.

- Yu Qi (2013) Interpretation of gynecological endocrine diagnosis and treatment guidelines-case analysis. People's Medical Publishing House.

- Lara-Torre E Spotswood L Correia N Weiss PM (2011) Intrauterine contraception in adolescents and young women: a descriptive study of use, side effects, and compliance. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 24(1): 39-41.

-

Guolin He, Xibiao Jia, Ran Cheng, Jinfeng Xu, Yu Xuan, Bing Peng. A Case Report of Severe Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy with Severe Liver Damage as the Main Manifestation. 5(1): 2021. WJGWH.MS.ID.000603.

ICP, Pregnancy, Prognosis, Bile acids, Liver transaminases aspartate aminotransferase, Liver alanine aminotransferase

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.