Research Article

Research Article

Foragers and Food Production in Africa: A Cross- Cultural and Analytical Perspective

Robert K Hitchcock*

Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Mexico

Robert K Hitchcock, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, Mexico.

Received Date: February 19, 2019; Published Date: March 26, 2019

Abstract

Virtually all hunters and gatherers in Africa today not only depend on foraging for their livelihoods but they also engage in food production and trade of domestic crops, livestock, and other resources. Many of them also take part in various kinds of work for other people in exchange for cash, food, and other goods. Drawing on case studies from western, central, eastern, and southern Africa, this paper assesses the causes and consequences of the shifts from hunting and gathering to agriculture, pastoralism, and small-scale business activities. Today, there are few ‘isolated hunter-gatherers’ who depend completely on foraging and are not enmeshed in the global, national, and local socioeconomic systems. Climate change, globalization, and the expansion of markets are leading to significant changes in local subsistence and livelihood strategies. These and other factors are also contributing to an expansion of innovative efforts to cope with the many serious challenges facing Africa’s indigenous peoples.

Foragers and Food Production in Africa: A Cross-Cultural and Analytical Perspective. Paper for the 48th annual Society for Cross- Cultural Research (SCCR) meetings, Jacksonville, Florida, February 13-16, 2019.

Introduction

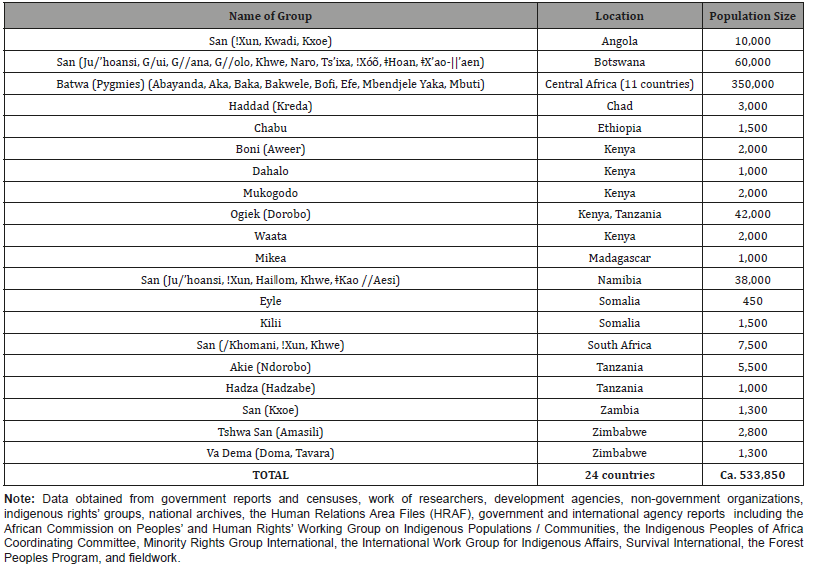

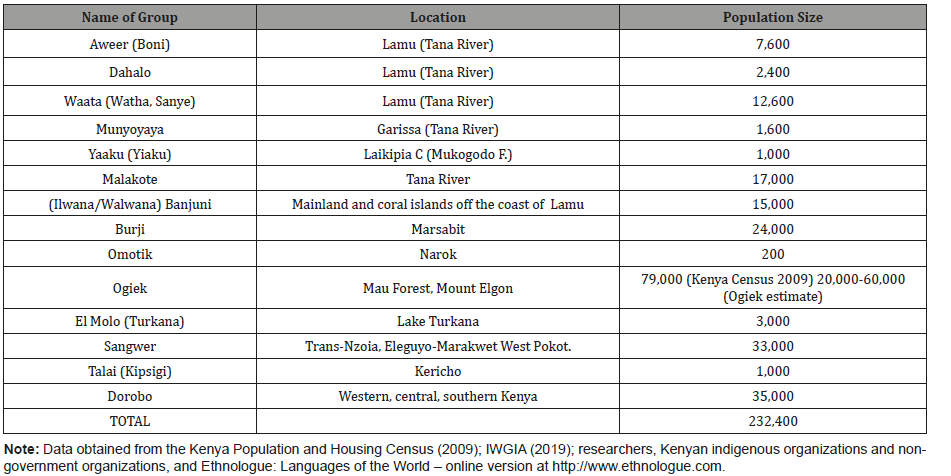

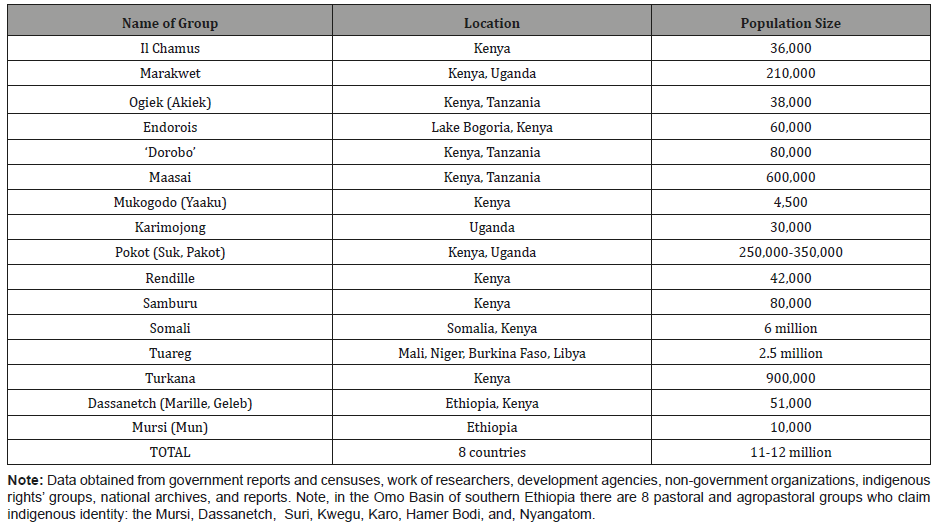

In Africa today, there are approximately 533,850 huntergatherers in 24 different countries on the continent (which contains a total of 54 nation-states) (Table 1). Some of the people who have been defined as hunter-gatherers or foragers include the Batwa (Pygmies) of Central Africa, occupying a dozen countries in the Congo Basin and its surrounding areas. In southern Africa, the San (Bushmen), reside in 7 countries, a large proportion of them in the Kalahari Desert, but some of them are also found in Afromontane areas such as the Maluti-Drakensberg Mountains of Lesotho and South Africa. There are also sizable numbers of former foragers who reside today in Central and East Africa, from the Haddad of Chad [1] to the Hadza of Tanzania [2] and from the Ogiek of Kenya to the Eyle of Somalia [3,4]. Virtually all of the huntergatherers and former foragers in Africa obtain a portion of their livelihoods from agriculture or from trade of wild meat and other forest products for domestic crops. A substantial number of former foragers raise their own crops, as seen, for example, among virtually all San, eastern African hunter-gatherers such as the Chabu and the Boni, and most if not all Batwa [5-8].

Off-label Prescription of Antibiotics

Environmental exposure to antibiotics is increasingly unavoidable in developing countries. Antibiotic use is valuable for livestock survival and if their use were denied a shortage in food products originating from livestock would be expected. Unsanitary conditions at farmhouses exist in rural areas where antibiotics are used to keep animals from becoming ill. Disease risk can be mitigated by improving sanitary conditions for animals, but it would be expensive to raise animals without using antibiotics. However, antibiotic product meant for human or veterinary use applied for unproven indication, or blindly used to get desired results in a manner not specified according to product characteristics, is an offlabel use that can be regarded as unethical. Another off-label use, in the absence of an authentic prescription, occurs when antibiotics are sold to users who (depending on their own knowledge) indulge in self-medication - mostly on a wider scale to include animal husbandry such as poultry, livestock, and humans.

Antibiotics Entering the Environment

Antibiotics, like many pharmaceuticals, enter the environment by many routes: from human use via hospital discharge, local sewerage treatment plants, and leachates from landfills. Antibiotics can enter surface waters from sewerage treatment plants specifically, or they can be exchanged through surface runoff from treated animals [4].

Indiscriminate discharge of water effluents has threatening consequences for public health and the environment. Exposure to polluted water is the prime cause of mortality for an overwhelming number of people. Estimates from the UN indicate that the world’s waterways receive 2 million tons of industrial, sewage, and agricultural waste each year [5]. The sewage muck (biosolids) used as a fertilizer in agricultural land areas can be the prime cause of ground water exposure to antibiotics [6].

Antibiotics may also enter the environment through manure use on soil and discharge by grazing domesticated animals [7]. Yang et al. [8] demonstrated the presence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in animal manures and an increase in antibiotic resistance of soil microbial populations exposed to such manure. Veterinary antibiotics can enter water bodies either specifically if treated animals enter surface water. Many antibiotics are inadequately ingested and not totally utilized in human and other large animals, especially mammals. Considerable antibiotic (30-90%) is discharged in urine and feces shortly after their ingestion as either the parent compound or as residuals [9]. Humans are therefore potentially and continuously exposed to water or soil already having antibiotic concentrations at lethal or sub lethal levels, which could result in human health implications by increasing antibiotic resistance (Figure 1).

Table 1: Population Sizes of Indigenous African Peoples Who Are or Were Foragers (Hunter Gatherers).

Agricultural crops may serve as a buffering resource to wild foods that are obtained through foraging, or they may represent the majority of the diet. The most common domestic crop grown by African forager-farmers is yellow corn (Zea mays, maize) followed by sorghum, millet, ground nuts, water melons and yams. Wild natural resources are managed carefully by African peoples. Some of the management practices include the use of fire to burn off vegetation cover and provide nutrients for soils, particularly tropical ferruginous soils. Planting is often staggered to take advantage of variability in rainfall. Many farmers utilize polyvarieties, planting different varieties of crops such as bananas or yams. Some farmers plant crops in different fields and gardens in order to take advantage of variability in rainfall and soil conditions.

The majority of Africans are small-scale rural farmers. They are all integrated into the local, national, regional and global economic systems. Even those people who reside in urban areas often have gardens where they raise vegetables and fruits and other crops. Most Africans have diversified sources of subsistence and income. The majority of Africa’s people are rural farmers and entrepreneurs who run small businesses such as small general dealerships and who are self-employed

Perspectives on Africa

• The total land area of Africa is 29,648,481 km2 (11,447,338 mi2)

• The current population of Africa is at 1,310,780,134 as of 24 March 2019, based on the latest United Nations estimates.

• The population density in Africa is 43 per km2 (113 people per mi2).

• Africa’s population is equivalent to 16.64% of the total world population.

• Africa ranks number 2 among regions of the world (roughly equivalent to “continents”), ordered by population.

• 40.6 % of the population of Africa is urban (523,004,491 people in 2018). Africa is the fastest urbanizing continent in the world.

• The median age in Africa is 19.4 years, youngest in the world.

• Africa’s working age population will reach 1 billion people by 2030.

Socioeconomic inequalities drive population-wide health disparities in Africa. According to Bread for the World (2016:3) social and economic factors such as housing, education, employment opportunities, and access to healthy food and water have a larger impact on impact on health outcomes than does medical care. Even as hunger rates decline in nearly every region of the developing world, including Africa, wide-scale malnutrition from vitamin and mineral deficiencies continues to impose devastating cost on individuals [9].

The continent of Africa is often seen incorrectly as a continent in decline, a part of the world where droughts, famine, disease, poverty, failed states, economic stagnation, corruption, and poorly thought out development projects are pervasive. The degree to which hunger exists among foragers and farmers varies across the continent (see, for example, [10] with respect to San in southern Africa). One of the issues that people raising grain crops like sorghum and millet deal with is Quelea finches (Quelea quelea the red-billed Quelea) which raid grain-producing areas on a regular basis. As a result, bird-scaring is an important part of the agricultural production process. Bird-scaring is often done by women and children, at least in southern and eastern Africa.

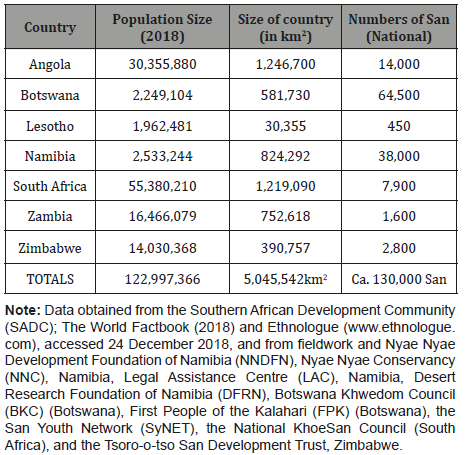

Discussions with local people in Africa provide insights into the various constraints that affect people who are just getting in to farming, or groups who engage in agriculture as a buffering strategy. Among Kalahari San, constraints included issues like elephants (Loxodonta africana) that got into the fields and gardens and destroyed the crops and water facilities. Such events occurred in Nyae Nyae, Namibia, western Ngami land, Botswana, and in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in late 2018. The San, who number some 130,000 people in 7 countries, are involved in agricultural production in a variety of ways, both directly and indirectly. There are cases where San work in the fields of other groups, and ones where they are engaged as agricultural laborers on commercial farms. At the same time, a sizable number of San raise crops of their own or obtain them through exchange with other people. San, like other African former foraging peoples, use a variety of techniques to attain a degree of food self-sufficiency.

Some of the constraints on agricultural production in Africa include spatial and temporal variations in rainfall, temperature variations, soil conditions, periodic droughts, floods, and cold spells, pests of a variety of kinds and plant diseases. Africa has some of the most innovative agriculture in the world [11-15]. Local people employ such innovative conservation agriculture techniques as no tillage systems, use of green mulch, broadcasting of mixes of seeds, plant cross-breeding, seed-saving, and planting a variety of crops in tropical forests where there is a canopy and a number of different vegetation layers, the trees providing shade for crops growing below.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 21 countries in Africa have a single export commodity [16-18]. One example of such an export commodity is cacao (Theobroma cacao), while another is coffee (e.g. Coffea arabica). Africa is the source of major crops that have affected the rest of the world: pearl millet, black-eyed peas, cassava, and ground nuts.

Agriculture varies across the continent, depending on rainfall, soils, fluctuations in temperature, and technological availability [11]. About 22% of Africa is made up of forests and woodlands, while there are also sav annas, deserts, temperate zones. mountainous areas, and inland and coastal deltas (e.g. the Niger Delta, the Sud Swamp in South Sudan, the Okavango Delta, and the Zambezi Delta in Mozambique). Some of the coastal deltas support mangrove swamps. Local farmers raise crops, engage in aquaculture, and fish in both the coastal and inland deltas.

Congo Basin is Africa’s largest contiguous forest and the second-largest tropical rainforest in the world. Covering about 1.3 million square miles (3.4 million square kilometers) the tropical forest contains portions of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Congo Republic, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. It is drained by the Congo River and its tributaries. The most extensive protected area in the Congo Basin is Upper Guinea Forest in Côte d’Ivoire’s 1,275-square-mile Tai National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The basin supports some of the largest undisturbed stands of tropical rainforest on the planet along with some large wetland areas. The climate is equatorial and tropical, with two main rainy seasons that includes high amounts of rainfall inputs and relatively high temperatures year round (Table 2).

Table 2: Numbers of San in Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

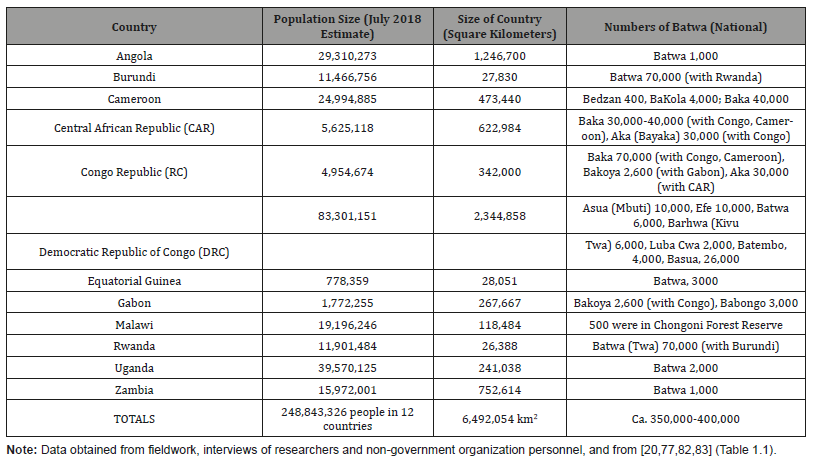

The Batwa (‘Pygmies’) of central Africa are well known to the international community and to researchers [5] (Table 3). Known to some as ‘forest peoples’ the Batwa of Central Africa are found in nearly a dozen countries, stretching from the Democratic Republic of Congo south to the woodlands of northern and western Zambia. Historically the Batwa of central Africa were tropical and subtropical forest hunter-gatherers who interacted to various degrees and in a variety of ways with neighboring farming peoples. Some Batwa are totally dependent on their farmer neighbors; others are semi-dependent, and a few Batwa groups are autonomous from their neighbors [19].

Table 3: Data on Batwa Populations in Central Africa.

It was once thought that tropical forests were the last places other than the high Arctic to be occupied by human populations, presumably because tropical forests lacked high quality starch resources. Tropical forest foraging groups had relatively high residential mobility, moving as frequently as every day or every few days [20,21]. They were or are dependent on a diverse array of resources. In some cases, they depended mainly on certain kinds of high-starch resources such as cassava, while also exchanging bush and forest products with their non-foraging neighbors. The Batwa have been affected substantially by processes of sedentarization, some of which was done at the hands of colonial and post-colonial government authorities.

The productivity of rainforests for hunter-gatherers has been the subject of intense debate [22-24]. In essence, the ‘wild yam’ question revolves around whether hunter-gatherers exploiting wild yams can support themselves in tropical forests, or whether they need to exchange wild meat, honey, and other products for domestic crops from farmers and villagers in order to sustain themselves when they are in the forests. Occupation of tropical forests in Africa appears to have occurred relatively late in hominin history, roughly in the Middle Stone Age (MSA). There is a variety of kinds of yams, but two are very important, the white yam (Dioscorea rotundata) and the yellow yam (Dioscorea cayenensis). These are both African in origin, and they represent the most important cultivated types. There are at least 200 varieties of these yams which are cultivated by Batwa and by farmers in the Central African rainforest and its margins. Cassava (manioc) is now the primary domestic food crop in the wetter western areas of the African continent.

Dry forests collectively account for the majority of Africa’s timbered lands [25,26]. African dry forests are some of the most extensive in the world, and open woodlands cover parts of the continent. The miombo woodland, for example, which is dominated by Brachystegia spp. trees, makes up over a million square miles of the Central and East African plateaus. The miombo woodland is located in areas to the south of the Congolese forests and the East African acacia savannas and stretches down to southern Africa. Agriculture in these areas consists of dryland agriculture, carried out with hand-held tools such as hoes and shovels, and plow agriculture with plowing teams ranging from 2 to 12 or more oxen or sometimes horses or donkeys. Many households have both agriculture fields, which can be up to a hectare in size, and gardens, which may be 100 square meters or more in size.

The mangrove swamps of tropical Africa’s coastlines are important when considering the continent’s forests. These diverse communities, consisting of a number of species of mangrove, trees and shrubs that are uniquely adapted to brackish estuaries and nearshore margins, are very important ecologically as well as socially and economically. The mangrove swamps provide a variety of ecological services, and they function as foraging areas for both terrestrial and marine animals, fish, amphibians, insects, crustaceans, and humans. The most extensive mangrove forest on the continent is along the Niger Delta where Ogoni and Ibibio and other groups forage, hunt, fish, and raise crops. These activities have been very much affected by decades of oil development in the Niger Delta by a series of different oil companies [27]. Biologically diverse mangrove swamps exist along the Indian Ocean coast, most significantly in the Rufiji and Zambezi River deltas. Locally bred rice is cultivated in the Niger Delta, and aquaculture is done in the Zambezi and Rufiji River Deltas.

There is a significant argument in the anthropological literature regarding the issue of abundance of food for huntergatherers [28,29]. Lee [30,31] argues that the Ju/’hoansi had a superabundance of wild plant foods, based on his assessment of the economic returns of foraging which he documented in July of 1964. Other analysts [32-34] argued that there were periods of scarcity and undernutrition over the year among Ju/’hoansi, due in part to seasonal cycling. It is clear that in order to understand the degree of well-being of hunter-gatherers and farmers, one needs to have long-term and multi-season data.

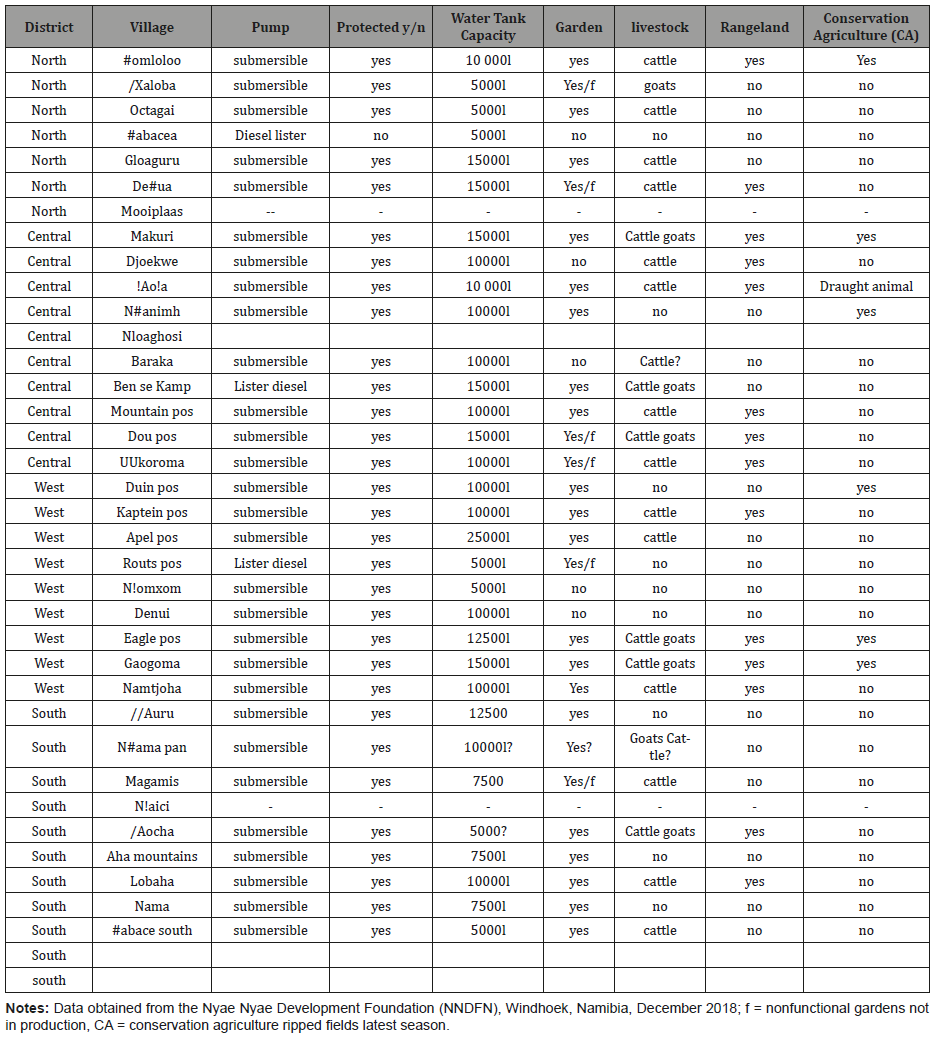

To take an example, using the Ju/’hoansi San of southern Africa, there are oscillations between foraging and farming over time [35,36]. In addition to a certain amount of foraging, some of the important economic activities of the Ju/’hoansi San of the Nyae Nyae region are agriculture and pastoralism [37-40]. In 2018, 27 of the 36 contemporary Nyae Nyae communities had gardens where they raised domestic crops (Table 4). These gardens are small, generally less than half an acre, and they are cultivated using hand tools including hoes, shovels, digging sticks, and pitch forks. Wheelbarrows are used to move crops and to carry plastic containers and buckets that are used for watering gardens. Most of these gardens are rain-fed, but there are also ones that are irrigated by water facilities provided by the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN), the Tradition and Transition Fund (TTF), and the Namibian government (the Ministry of Agriculture, Water, and Forestry). A variety of domestic crops are grown in the gardens which in 2018 numbered 18 species. These include the following:

Table 4: Nyae Nyae Village Water Facilities, Gardens, Livestock, Rangelands, and Conservation Agriculture.

beans (Phaseolus mungo, mung bean, and Phaseolus acutifolius, teppary bean)

beetroot (Beta vulgaris)

cabbage (Brussica oleracea)

cauliflower (Brassica oleracea)

carrot (Daucus carota)

cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata)

guava (Psidum guajaya)

maize (Zea mays)

melon (sweet melon, Cucumis melo)

millet (pearl millet, Pennisetum typhoid’s)

onion (Alliumcepa spp.)

pawpaw (papaya) (Carica papaya)

pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo)

sorghum (Sorghum bicolor)

spanspek (cantaloupe) (Cucumis melo, var. cantalupensis)

sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.)

tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)

tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)

Challenges to the agricultural production systems in Nyae Nyae include spatial and temporal variability in rainfall, periodic drought and floods, limited soil fertility, breakdowns in the water systems, destruction of water points and gardens by wild animals including elephants and other large mammals, and predation of livestock and small stock by lions, leopards, hyenas, and other animals. There are also problems in gardening work due to conflicts among individuals in the communities over access to tools and labor inputs [73]. Overcoming the various constraints and addressing labor and land use conflicts has been an important area of emphasis for the Ju/’hoansi and the organizations with whom they work.

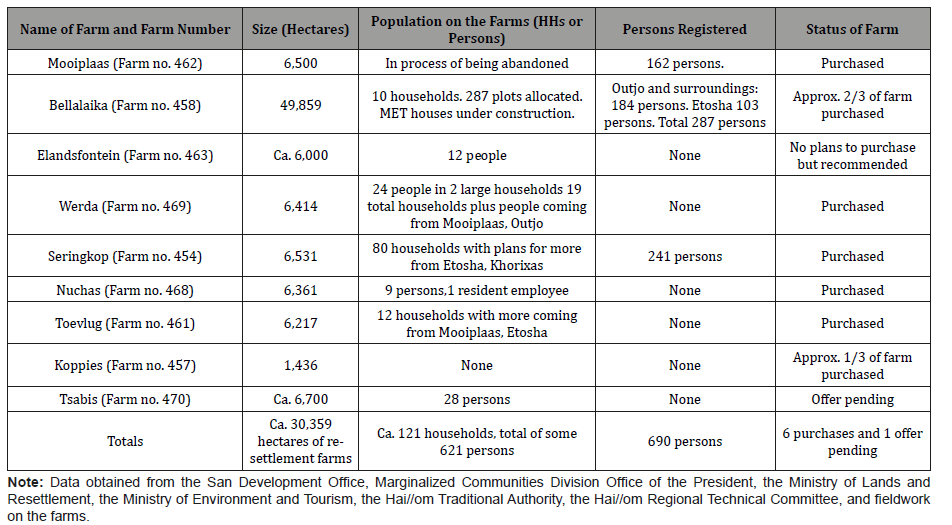

Other examples of San food production range from dryland cultivation of crops in the Central Kalahari of Botswana [41] to irrigated fields and gardens among the Hai//om San in the resettlement farms of central Namibia (Table 5) [10,42-44]. Many of the Hai//om resettlement farmers had worked on commercial (freehold) farms in Namibia where they had learned to care for livestock and to help produce crops, often for the farm owners. It should be stressed that in the Kalahari, some of the San engaged in what was known as majako, working in the fields of other people in exchange for a portion of the crop produced.

Table 5: Hai//om Resettlement Farm Size, Population and Farm Purchase Status.

Conclusion

Several conclusions can be drawn about foraging and food production in Africa. Virtually all people who historically were known as foragers in Africa either produce some domestic crops or obtain them through exchange or purchase. Women and children play important roles in African agriculture, engaging in activities ranging from field preparation to planting, weeding, bird-scaring, harvesting, post-harvest processing, and storage. Those societies which use plows, and which raise livestock (i.e. many of which are agropastoralists) have men involved especially in the plowing and planting process.

The assemblage of crops that can be grown in Africa varies significantly from one ecological zone to another [45-49]. There are roughly five different ecological zones that have different kinds of agriculture: the rain forest, the savanna, the dryland forests, desert areas, and the winter rainfall zone (e.g. portions of North Africa near the Mediterranean and the Cape of South Africa). Swidden (shifting cultivation) techniques are used in the rainforest areas, where portions of the forest are burned off, cultivated, and abandoned, the farmers moving on to other places. As population growth has occurred, forest farmers have had to intensify their production and reduce their mobility. Households of shifting cultivators often have gardens where they grow bananas, pumpkins, mangos, and sweet potatoes. It is not just soil exhaustion that leads to movement of farm households; this also may be due to an increase in weeds and to social issues such as interhousehold disagreements (Table 6&7).

Table 6: Population Sizes of Kenyan Peoples Who Are or Were Hunter Gatherers.

Table 7: Population Sizes of East African Pastoralists and Agropastoralists who are considered indigenous.

In savanna zones, a combination of horticulture and agriculture is practiced. Many of the households have diversified production systems, combining a small amount of foraging with food production, trading, and small-scale business activities. Foragers, farmers, and pastoralists are interconnected in a variety of ways. Farmers allow cattle and other domestic animals to graze on the stubble left in the fields after the harvest, providing high-value nutrients to the domestic animals. A key factor in areas where plow agriculture is practiced is the availability of oxen or other draught animals for plowing purposes. The later one plows, the more likely it is that crop losses will be suffered because of rainfall deficiency. Sometimes in savanna zones planting is done twice or more in order to take advantage of rainfall variation. Manure from livestock is used for fertilizing the fields, and dung is also used as fuel. Water from hand-dug wells is used for domestic crops, and irrigation is practiced in many parts of the savanna zones, some of it using small-scale canals and some of it through piped water, as can be seen, for example, in the Kalahari.

The Chabu of the southwestern highlands of Ethiopia combine foraging and food production [50-53]. Crop failure due to droughts is not uncommon in southwestern Ethiopia, so Chabu, like other hunter-gatherers, rely on agriculture as a buffering strategy. They also trade for agricultural products with villagers. The Haddad of Chad grow a vareity of crops and, like other foragers, their reliance on a diverse range of crops has expanded over time [1]. The same is true for the Tshwa San of western Zimbabwe [54]. It is interesting to note that of the 149 Tshwa households surveyed in Tsholotsho, Zimbabwe, only 4 had cattle of their own, but 90% of them engaged in agriculture.

African hunter-gatherers, like the Pumé of Venezuela, diversify their domestic crops in some cases, or they may replace their wild plant foods with cultivated species [55,56]. Cultigens generally do not completely replace wild foods among hunter-gatherers. Cultivators, too, rely heavily on wild plants, as seen, for example, among the Gwembe Tonga of northern Zimbabwe and southern Zambia [29]. The expansion of large dams in Africa has led to changes in the foraging and food producing practices of large numbers of African people [57].

A major constraint facing foragers and small-scale food producers in Africa relates to the issue of security of land tenure. Most African foragers and farmers live in communal areas of the continent, where they do not have de jure (legal) rights to land. As a result, they often have to seek the right to establish agricultural fields from local traditional authorities or land boards, and they face the possibility of being evicted, something that has happened to former foragers such as the Aweer (Boni) of the Tana River area in Kenya, the Chabu of Ethiopia, the Tshwa of Zimbabwe and northeastern Botswana, the Naro San of Ghanzi and Kgalagadi Districts, Botswana, and the !Xun of northern Namibia. The Khwe San of Bwabwata National Park in the Zambezi Region of Namibia are some of the few African peoples who are allowed to cultivate crops in a national park [57,58]. In most protected areas in Africa, cultivation of crops is not allowed.

Boone [38] and Chimbowu [59] have examined the complex issue of communal land reform, land titling, and land registration in Africa, a subject that Liz Alden Wily and her colleagues in Land Mark have explored in considerable detail [60-63]. Fortunately, collective land ownership rights are being recognized legally in a number of African countries, including Burkina Faso, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda [64- 70]. There are also countries like Botswana, Cameroon, and Gabon where the legislation protecting communal rights is extremely weak, and some countries, such as the Central African Republic, Chad, Eritrea, and Rwanda where there is no discernible legal provision for community landholding [71-76] (Table 3).

Lacking title to land in communal areas of Africa, which make up a considerable portion of the African continent, leaves many African communities vulnerable to expropriation or eviction, issues that have to be faced today by African governments, international organizations, and African peoples. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that many African hunter-gatherers, farmers, and agropastoralists support the right to food [64]. Most of them also want both diversified agricultural development and equitable and socially just land reform programs put in place [77-84].

Acknowledgement

Support of some of the research upon which this paper is based was provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant BCS 1122932), Brot für die Welt (Project No. 2013 0148 G), the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) (Grant No. 2098), the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) (grant No. 2650), the Millennium Challenge-Account-Namibia (MCA-N), the United States Agency for International Development, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the World Bank, and Hivos (The Netherlands).

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Nicolaisen, Ida (2010) Elusive Hunters: The Haddad of Kanem and the Bahr el Ghazal. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Marlowe FW (2010) The Hadza: Hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Stiles, Daniel (1981) Hunters of the northern East African coast: origins and historical processes. Africa 51(4): 848-862.

- Stiles, Daniel (1982) A history of the hunting peoples of the northern East Africa coast: ecological and socio-economic considerations. Paideuma 28: 165-174.

- Hewlett Barry S (2014) Hunter-gatherers of the Congo Basin: Cultures, histories, and biology of African Pygmies.

- Köhler A, J Lewis (2001) Putting hunter-gatherer and farmer relations in perspective: A Commentary from Central Africa. In Ethnicity, huntergatherers, and the ‘other’: Association or Asimilation in Southern Africa? Susan Kent eds. Pp. 276-305.

- Wilkie, David (1988) Hunters and Farmers of the African Forest. In People of the Tropical Rain Forest, Julie Sloan Denslow and Christine Padoch, eds., Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 111-126.

- Wilkie, David (1989) The Impact of Roadside Agriculture on Subsistence Hunting in the Ituri Forest of Zaire. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 78(4): 485 494.

- Bread for the World (2016) Hunger Report: The Nourishing Effect. Ending Hunger, Imposing Health, Reducing Inequality. Washington.

- Dieckmann, Ute (2018) The Status of Food Security and Nutrition of San Communities in Southern Africa. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Christiansen Luc, Lionel Demery (2018) Agriculture in Africa: Telling Myths from Facts.

- Harrison, Paul (1989) The Greening of Africa: Breaking Through in the Battle for Land and Food. London: Grafton Books for the International Institute for Environment and Development (Earthscan).

- Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) (1988) Enhancing Agriculture in Africa: A Role for US Development Assistance. Washington DC: Office of Technology Assessment, Congress of the United States.

- Mc Cann, James C (2005) Maize and Grade: Africa’s Encounter with a New World Crop 1500 to 2000. Cambridge, Massashusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Peters, Charles E (2018) Managing the Wild: Stories of People and Plants and Tropical Forests. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2006) State of Food Insecurity 2006. Rome: The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018a) The State of Food Insecurity and Nutrition in the World: Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2018b) High-Level Expert Seminar on Indigenous Food Systems, Rome, 7-9 November 2018. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Hladik CM, S Bahuchet, I de Garine (1990) Food and Nutrition in the African Rain Forest. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- Bahuchet, Serge (2014) Cultural Diversity of African Pygmies. In Hunter- Gatherers of the Congo Basin: Cultures, Histories, and Biology of African Pygmies, Barry S Hewlett, eds., pp. 1-29.

- Binford Lewis R (2001) Constructing Frames of Reference: An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Ethnographic and Environmental Data Sets.

- Bahuchet SD, Mc Key, I De Garine (1991) Wild Yams Revisited: Is Independence from Agriculture Possible for Rainforest Huntergatherers? Human Ecology 19: 213-243.

- Bailey Robert C, Thomas N Headland (1991) The Tropical Forest: Is it a Productive Environment for Human Foragers? Human Ecology 19(2): 261-285.

- Yasuoka H (2006) Long-term foraging expeditions (molongo) among the Baka hunter-gatherers in the northwestern Congo Basin, with special reference to the “wild yam question.” Human Ecology 34(2): 275-296.

- Wily, Liz Alden, S Mbaya (2001) Land, People and Forests in Eastern and Southern Africa at the Beginning of the 21st Century. Nairobi: IUCN.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2018c) The State of the World’s Forests: Forest Pathways to Sustainable Development. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Watts, Michael eds. (2008) Curse of the Black Gold: 50 Years of Oil in the Niger Delta. Brooklyn: power House Books.

- Sahlins, Marshall D (1968) Notes on the Original Affluent Society. In Man the Hunter, Richard B Lee and Irven DeVore, eds., Chicago, Pp. 85-89.

- Scudder, Thayer (1971) Gathering among African Woodland Savanna Cultivators: A Case Study. Zambia Papers No. 5. Livingstone: Rhodes- Livingstone Institute for African Studies.

- Lee, Richard B (1968) What Hunters Do for a Living, or, How to Make Out on Scarce Resources. In Man the Hunter, Richard B Lee, Irven De Vore, eds., Chicago, pp. 30-48.

- Lee, Richard B (1969) Kung Bushmen Subsistence: An Input Output Analysis. In Environment and Cultural Behavior, Andrew P Vayda, eds., Natural History Press, New York, pp. 47-79.

- Wilmsen, Edwin N (1978) Seasonal Effects of Dietary Intake on Kalahari San. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Proceedings 37(1): 65-72.

- Wilmsen, Edwin N (1982) Studies in Diet, Nutrition, and Fertility among a Group of Kalahari Bushmen in Botswana. Social Science Information 21(1): 95-125.

- Wilmsen, Edwin N (1989) Land Filled with Flies: A Political Economy of the Kalahari. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Campbell AC (1986) The Use of Wild Food Plants, and Drought in Botswana. Journal of Arid Environments 11(1): 8l-9l.

- Wiessner, Polly (1977) Hxaro: A Regional System for Reducing Risk among the !Kung San. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

- Biesele, Megan, Robert K Hitchcock (2013) The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian Independence: Development, Democracy, and Indigenous Voices in Southern Africa. Paperback Edition.

- Boone, Catherine (2019) Legal Empowerment of the Poor through Property Rights Reform: Tensions and Trade-offs of Land Registration and Titling in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Development Studies 55(3): 384-400.

- Wiessner, Polly (2003) Owners of the Future? Calories, Cash, Casualties, and Self-Sufficiency in the Nyae Nyae Area between 1996 And -2003. Visual Anthropology Review 19(1-2): 149-159.

- Wiessner, Polly W (2014) Embers of Society: Firelight Talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(39): 14027-14035.

- Ikeya, Kazonubu (1996) Dry Farming among the San in the Central Kalahari. African Study Monographs Supplement 22: 85-100.

- Dieckmann, Ute Kunene, Oshana, Oshikoto Regions (2014) In “Scraping the pot”: San in Namibia Two Decades after Independence, U Dieckmann, M Thiem E Dirkx, J Hays eds., pp. 173-232.

- Friederich, Reinhard (2014) Etosha: Hai//om Heartland: Ancient Hunter-Gatherers and their Environment. Horst Lempp, editor. Windhoek: Namibia Publishing House.

- Lawry, Steven, Ben Begbie Clench, Robert K Hitchcock (2012) Hai// om Resettlement Farms: Strategy and Action Plan. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism and Millennium Challenge Corporation, September 2012.

- Grove AT (1989) The Changing Geography of Africa. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Harris David R (1969) Agricultural Systems, Ecosystems, and the Origins of Agriculture. In the Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals, Peter J Ucko and GW Dimbleby eds. pp. 3-15.

- Harris David R (1972) The Origins of Agriculture in the Tropics. American Scientist 60: 180-193.

- Harris David R, Gordon C Hillman, eds. (1989) Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation. London: Unwin Hyman.

- Nyerges A Endre (1997) The Ecology of Practice: Studies of Food Crop Production in Sub-Saharan West Africa. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers.

- Dira, Samuel Jilo (2016) Learning to survive social-ecological risks: cultural resilience among Sidams farmers and Chabu forager-farmers in Southwestern Ethiopia. PhD thesis. Vancouver, Washington: Washington State University.

- Dira, Samuel Jilo, Barry S Hewlett (2016) Learning to Spear Hunt Among Ethiopian Chabu Adolescent Hunter-Gatherers. In Social Learning and Innovation in Contemporary Hunter-Gatherers: Evolutionary and Ethnographic PerspectivesHideaki Terashima, Barry S Hewlett eds, pp. 71-82.

- Dira, Samuel Jilo, Barry S Hewlett (2017) The Chabu hunter-gatherers of the highland forests of Southwestern Ethiopia. Hunter-Gatherer Research 3(2): 323-352.

- Dira, Samuel Jilo, Barry S Hewlett (2018) Cultural Resilience among the Chabu Foragers in Southwestern Ethiopia. African Study Monographs 39(3): 97-120.

- Hitchcock, Robert K, Begbie Clench, Benjamin, Ashton Murwira (2016) The San in Zimbabwe: Livelihoods, Land and Human Rights. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) and Johannesburg: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA), and Harare: University of Zimbabwe. IWGIA Report 22.

- Kramer, Karen L, Russell D Greaves (2016) Diversify or Replace: What Happens to Wild Foods when Cultigens are Introduced into Hunter- Gatherer Diets. In Why Forage? Hunting and Gathering in the 21st Century, Brian F. Codding and Karen L. Kramer, eds, pp. 15-42.

- Kramer, Karen L, Russell D Greaves (2017) Why Pumé Foragers Retain a Hunting and Gathering Way of Life. In Hunters and Gatherers in a Changing World, Victoria Reyes García, Aili Pyhälä, eds., pp. 109-126. London.

- Scudder, Thayer (2019) Large Dams: Long Term Impacts on Riverine Communities and Free Flowing Rivers. Cham, Springer.

- Paksi, Attila and Aili Pyhälä (2018) Socio-economic Impacts of a National Park on Local Indigenous Livelihoods: The Case of the Bwabwata National Park in Namibia. In Research and Activism among the Kalahari San Today: Ideals, Challenges, and Debates, Fleming R Puckett and Kazunobu Ikeya, eds. pp. 197-214.

- Chimhowu Admos (2019) The ‘new’ African customary land tenure. Characteristic, features and policy implications of a new paradigm. Land Use Policy 81: 897-903.

- Wily, Liz Alden (2011) ‘The Law is to Blame’: The Vulnerable Status of Common Property Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa. Devevelopment and Change 42(3): 733-757.

- Wily, Liz Alden (2012) Customary Land Tenure in the Modern World. Washington DC: Rights and Resources Initiative.

- Wily, Liz Alden (2015) Estimating National Percentages of Indigenous and Community Lands: Methods and Findings for Africa. Washington, DC: LandMark.

- Wily, Liz Alden (2018) Collective Land Ownership in the 21st Century: Overview of Global Trends. 7(2): 68.

- Wily, Liz Alden (2018) Collective Land Ownership in the 21st Century: Overview of Global Trends. 7(2): 68.

- Lambek Nadia, P Claeys, A Wong, L Brilyamyer (2014) Rethinking Food Systems: Structural Challenges, New Strategies and the Law. New York and London: Springer.

- Alvarez, Stephanie, Carl J Timler, Mirja Michalscheck, Wim Paas, Katrien Descheemaeker, et al. (2018) Capturing farm diversity with hypothesisbased typologies: An innovative methodological framework for farming system typology development. PLoS ONE 13(5): e0194757.

- Binns, Tony, Kenneth Lynch, Etienne Nel, eds. (2018) The Routledge Handbook of African Development. New York: Routledge.

- Greta C Dargie, Simon L Lewis, Ian T Lawson, Edward TA Mitchard, Susan E Page, et al. (2017) Age, extent and carbon storage of the central Congo Basin peatland complex. Nature 542: 86-90.

- Flannery Kent V (1972) The Cultural Evolution of Civilizations. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3: 399-426.

- Flannery, Kent V (1973) Origins of Agriculture. Annual Review of Anthropology 2: 271-310.

- Food and Agricultural Organization (2005) Voluntary Guidelines to support the progressive realization of the right to adequate food in the context of national food security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Food Insecurity Vulnerability Mapping System (FIVIMS) (2003) Proceedings: Measurement and Assessment of Food Deprivation and Undernutrition. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization.

- Hitchcock, Robert K. (2019) Domestic Crop Production among the Ju/’hoansi San of Nyae Nyae, Namibia: Ethnoarchaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives. Paper prepared for a symposium titled ‘Archaeology on the Edge(s): Transitions, Boundaries, Changes, and Causes.’ Pei Lin Yu, Matthew Schmader, Robert K Hitchcock, organizers. Society for American Archaeology (SAA) 84th annual meetings, Albuquerque, New Mexico, pp. 10-14.

- Jacquelin Andersen, Pamela, ed. (2018) The Indigenous World 2018. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Lee, Richard B (2016) ‘In the Bush, the Food is Free: The Ju/’hoansi and Tsumkwe in the Twenty-First Century. In Why Forage? Hunting and Gathering in the Twenty First Century, Brian F Codding and Karen L. Kramer, eds., University of New Mexico Press, pp. 61-87.

- Mäkelä, Laura (2018) Gardening Opportunities as a Part of the Khwe San People’s Food Security in the East Bwabwata National Park. Master’s thesis Department of Agriculture Sciences Agroecology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

- Olivero, Jesús, John E Fa, Miguel A Farfán, Jerome Lewis, et al. (2016) Distribution and Numbers of Pygmies in Central African Forests. PLOS One 11(1).

- Patin E, Siddle KJ, Laval G, Quach H, Harmant C, et al. (2014) The impact of agricultural emergence on the genetic history of African rainforest hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists. Nature Communications 5: 3163.

- Sahlins, Marshall D (1972) Stone Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine.

- Taylor, Scott D (2019) Can Business Rights Alleviate Group-Based Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa? Understanding the Limits to Reform. The Journal of Development Studies 55(3): 420-436.

- Tauli Corpuz, Victoria (2018) Concept Note: Report by the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Ms. Victoria Tauli- Corpuz on the Criminalization and attacks (on) indigenous peoples Defending their Rights: Proposals for Action to Prevent and Protect. Geneva: Office of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous peoples.

- World Bank (2015) Botswana Poverty Assessment. Washington, DC: The World Bank, March 2015.

- World Bank (2018) The State of Social Safety Nets 2018. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- WWAP (United Nations World Water Assessment Programme)/UNWater (2018) The United Nations World Water Development Report 2018: Nature-Based Solutions for Water. Paris, UNESCO.

-

Robert K Hitchcock. Foragers and Food Production in Africa: A Cross-Cultural and Analytical Perspective. World J Agri & Soil Sci. 1(5): 2019. WJASS.MS.ID.000522.

-

Foragers, Food Production, Cross-Cultural, Analytical Perspective, Climate change, Globalization, Agricultural crops, Rain fall, Soil, Vegetables and fruits

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.