Research Article

Research Article

Rethinking Traditional Irrigation Water Equity in Holetta River, Awash River Basin, Ethiopia

Getamesay Shiwenzu, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Ethiopia.

Received Date: May 16, 2019; Published Date: June 11, 2019

Synopsis

The main objective of the study was to assess the equity of Holetta River to traditional irrigation users. In the study both qualitative and quantitative research approaches were used. By Purposive and convenient sampling methods open ended questionnaire and unstructured interview were employed along with direct observation. From the study the range is not serious however there is a problem of equity in water distribution to users. The water distribution doesn’t account for the type of crop and its stage, land hold and distant from the primary channel. Also, farmers unlawful act makes problems on ensuring equity. It worsens that there is no participation of females on equity of water. Thus, to improve equity, the management of the irrigation is important and development of strategies that facilitate resource equity and sustainability in the country among the community and other users should be considered. This study may give community concerns at local level and the future it is imperative to study details of social-economic and legal aspects while developing irrigation system in the country to bring equity and sustainability.

Keywords: Equity; Irrigation; Holetta river

Introduction

Traditional irrigation system has been practiced in the highlands of Konso (Ethiopia) for centuries [1]. Traditional irrigation schemes built through self-help program carried out by farmers on their own initiative and varies from less than 50 ha to 100 ha. Water committees administer the water distribution and coordinate the maintenance activities of the schemes [2]. The total irrigated area under this is estimated to be about 138,000 ha and about 572,000 farmers are involved. It is also very common in peri-urban areas, particularly in Addis Ababa and Bahir Dar, for the production of vegetables for the local market [3].

Current survey reveals evident successes on some schemes, where farmers admitted satisfaction in terms of improvement in incomes, as well as expansion of schemes (farm area) due to increased accessibility to water. However, evidence of conflicts between traditional irrigators and those on modern schemes regarding property rights to water creates a need for clearer water and irrigation management policies, which could be a basic framework for clear definition of water rights. Clearly defined rights to land and water are very crucial and must be considered in project design and implementation, if modest investments from farmers are to be expected in land improvement and other production enhancing activities [4].

In Holetta town of Madda Guddina village (kebele), the traditional irrigation user has water user associations with seven committee representatives. To control the water sharing among four stations the committee and users appoints two water dividers in each station. Each station would get water for 48 hours except station four gets 30 hours which the water moves out to other kebele. They also have irrigation bylaws to punish those who violate the rules.The bylaw is a simple guideline rather than legal rules. From experience farmers not well obey the law of water users’ associations. Thus, the research carries out to assess equity of Holetta river water to its traditional irrigation users. Also, to improve gender effects in water sharing and propose technical and managerial solutions to the problems of equitableness.

Methodology

Holetta is a town in central Ethiopia located in the Oromia region. This town has a latitude and longitude of of 9° 3 0’’ N 38° 300’’ E, , 9.05; 38.5 and an altitude of 2391 meters above sea level. The town also hosts a research station of the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research founded in 1966; this station is the national center for research to improve the yield of barely, highland oil crops, potatoes, and dairy products. Holetta was the first place in Ethiopia to have a permanent water mill, built in 1909 on the Holetta River [5]. Currently the town is divided in to 8 kebeles and different governmental and non-governmental institutions [6].

Based on figures from the Central Statistical Agency (2005), Holetta Genet has an estimated total population of 30,007 (14,825 were men and 15,182 were women) [5]. While from Holetta town Administration (2011), in 2010 census the population is 36,705. In general, Madda Gudina Kebele has 1219 population of which 594 and 625 are male and female, respectively.

Holetta River is a perennial river with catchment area of 156 m2and 64 m3/sec of its maximum probable flood discharge from hydrology analysis. There are 145 households who use the river with furrow irrigation to their 100 hectares of land for horticultural and other field crops production. As seen from the command area the farmers have long experience on traditional irrigation cultivating specially potato and they sell their product at Addis Ababa. Beside on the traditional irrigation in Madda Gudina and 03 Kebele, Holetta research center has a command area of 50 hectares that use the river for irrigation by traditional way [6] (Figure 1).

The minimum and maximum temperature of the site is with range to 6 and 24°c respectively. Annual rainfall is about 1100 mm and altitudes approaches to 2400m and clay loamy/red/ soil exist in the site. From Holetta town administration small scale irrigation project document (2010), recommended crops are potato, onion, garlic and tomatoes on the first cropping seasons with full irrigation. In second cropping also include cereal, wheat, and barely. The recommendation came from physical and social factors.

This study includes one village (Kebele) traditional irrigation users that use Holetta River for agriculture purposes that led by the community through water users’ associations. From Schell (1992), a case study is a research method common in social science. It is based on an in-depth investigation of a single individual, group, or event. Due to this the researcher chooses a case study to raise detail and intensive analysis of the community. Both primary and secondary data sources were utilized in the study. The researcher takes up primary data collected through irrigators and relevant officials at town and kebele level in-person (face-to-face) interviews, questionnaires and direct observation of the site. For interpreting and validating results, combining qualitative and quantitative methods provides a richer, contextual basis [7]. Collecting different kinds of data by different methods from different sources provides a wider range of coverage that may result in a fuller picture of the unit under study than would have been achieved otherwise [8].

Before the households were selected for survey, the researcher made discussion with irrigation and agronomy expertise and certain households. Among 145 households that cultivate 100 hectare of land, 24 households were purposively selected for the questionnaire survey. Also, from the four irrigation stations, the three stations were selected for the study. The selection of households and stations was dependent on the data from reconnaissance findings.

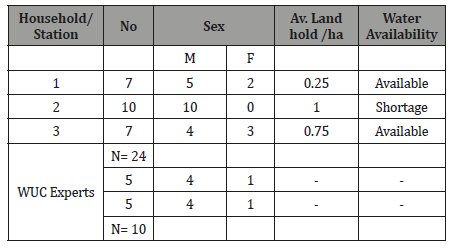

Convenient sampling was used to get 10 respondents for key informant interview to support the questionnaire collected. Five irrigation and agronomy professionals from Holetta town and Wolmera Woreda (district) agriculture office and five water user’s committee members from farmers were interviewed. From both categories one female on each had been get for the interview.

The selection of the household for interview from each station was attributed to the researcher perceptions that came from the prior visit to the study area. The respondents from each station were classified and arranged based on the land size and availability of water. It was difficult to include female-head due to the fact that they mostly have rented in/ shared in their plot to others or they hired to their children. But the researcher tried to include almost 20% from the total interviewed household (See Table 1).

Table 1:Total No of household, water user committee (WUC) and experts interviewed.

The process of analysis has been carried out by using qualitative description and descriptive statistics. To analyze, the data on social aspects, Statistical Package for Social Science /SPSS/ (Version 17) used. Non-quantifiable data from open-ended questions, key informant interviews, and direct observation have been discussed through qualitative description.

Result and Discussion

Water allocation and distribution

From key informant interview result water dividers at the station distribute and allocate water for farmers. The respondents confirmed that water dividers at every station does not distribute and allocate water among the farmers equally. In addition to unfair distribution of water farmer also violates the schedule set by the committee.

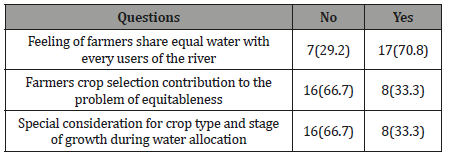

Similarly, about 30 percent of the respondents feel they share unequal water from other users in the irrigation system. They explain that the most important cause is water allocations not performed well and water divider misuse their power. Some of them said also the capacity of the local administration to make the community able to manage the irrigation is very low (Table 2).

Table 2:Water allocation and distribution.

Due to equity problems two groups appeared which get more and less. They further put that station one and three get more due to its proximity to the primary channel. Also, youth, stronger one and who rent their plot get more water by forcefully. Differently those who get less water are, station two, weak, elders, female and female head and also those who has small plot. Farmers said that they do not take anything in response of this but sometimes they would ask the water divider to get more though doesn’t get water. However, water allocation and distribution systems among users should be adjusted by considering problems of female-headed household and elders [2] (Table 2).

While key informant interviewed feel that they share equal water with other. Further explains about responsible organ who ensure equity are complex. Some gives to water user representatives and water divider as responsible body. Others said in cooperation of the committee and the local administration. As well, farmers suggested also that the committee and chief of the committee are responsible.

This might imply that Water Users Association (WUAs) of the new initiatives strategies do not evolve from the traditional system. Instead, the structure is largely imposed by government agencies and the donor community [9]. The long-run sustainability of these institutions often remains questionable. In general, it seems desirable to use existing local organizations. If the existing organizations are insufficient or inadequate for the purpose, careful analysis should lead to the design of facilitating organizations congruent with local culture [10].

In addition, the type of crop which farmers used does not contribute to the problem of equity of water is assumed almost by 66.7% of the interviewed farmers. They divided in to two which halves of them examines that the crop is high water demanding and others say demanding low however both argues the water is enough. The remaining percent of farmers perceived that due to high water demand from the crop all may not get water equally and shortage formed. Though there is no special consideration for crop type and stage of growth for water allocation in some cases this may be seen by the committee and water divider when farmers convince higher need of water for their field. As general rule farmers have to use already given period. All farmers water their crop up to the rates met for their crop growth and development acquiring from long experience.

Water distribution and allocation from experts’ viewpoints was found out that there is no equal distribution of water among the farmers. The bylaw practiced at the localities doesn’t consider the land size of the farmers and it is simply based on the duration of watering the plot. It is possible to ensure the equity of irrigation water through scientific way of water allocations. Hence, the experts responded that improved cropping calendar, propose crop water requirement, construction of modern closed channel and diversion structure, crop intensification and the community awareness toward modern irrigation systems and water allocation based on the size of the land should become in to practices to alleviate the water equity problems existed in the study area [11,12,19].

Sufficiency of the irrigation water

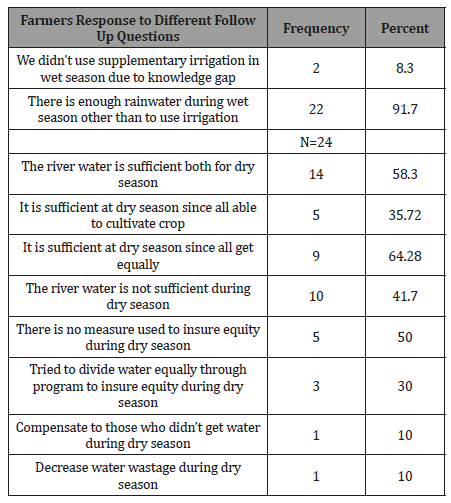

The sustainability of the irrigation water is determined by different factors such as porosity of the soil, the discharge of the river, method of irrigation and others. From Table 3 below, 90 % of farmers not use supplementary irrigation during wet season. The others whereas tried to take use. The main reason for farmers not uses both rain and irrigation at the same time are the rain is enough for production and a smaller number of them has a knowledge gap of how to use it [13].However, other study regards that farmers tried to maximize their benefit through utilizing the synergetic effect of both irrigated and rain fed systems since some crops are sown under irrigated systems but are grown and matured in rainy season and vice versa [2].

From gathered information 58.3 % of farmers believes the river is sufficient in dry seasons. Nevertheless, the others think that there is possibility of water shortage in the dry season. On the other hand, the justifications for its adequacy in dry seasons are all get water equally and there is option for cultivation in the dry season (Table 3)

Table 3:Sufficiency of the river and rainwater for irrigation.

Farmers from experience they have knowledge and understanding when the river water is reduced. Mostly it is reduced from January to May when there is no spring rain and in general they need the irrigation from September to May. In relation to scheme supply of Holetta River, farmers cropping pattern and season showed that highest irrigated area per percentage is at November to February. Whereas percentage of irrigated area is less in March- May including September. During summer there is no irrigation activity since the rain fall is enough [14]. On the other hand, as such a measure not used to ensure equity in dry seasons in the midst of users. Already water distributed by settled programs but in some extent, water may give to those who do not get enough amounts and also decreasing of water wastage being done by maintaining the channels.

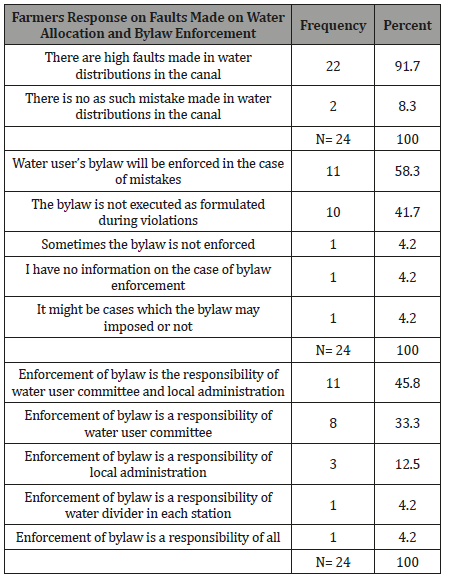

Water distribution faults and irrigation bylaws

As shown in Table 4, farmers violate water distributions in the canals. The degree of faults is high in that area. Types of faults are displacing the canals water to their field.To correct this and other aspects the community bylaws did not executed as of formulated.

All farmers place their assumptions to what the bylaws declare. They did not well understand what statements of bylaws say for diverse condition. In the statement there would be punishment ranging from warning to money up to prison. It penalizes 10-50 Birr those who break water distribution program in/out of stations. In the case of out of the station the punishment is high. Those who are not participating in campaign works and that damage other field would be punished by accounting day labor payment in the area and pay the loss of the product in the field for both circumstances (Table 4).

Table 4:Water distribution faults made by users and enforcements of bylaws.

The weaknesses of enforcing bylaws are going to the village and committee capacity. The committee does not give attention for its enforcement. It is not that much but water distributors and the committee susceptible to corruption. But mostly both fears to punish those who disobey due to not harming their neighborhood and others also not harming the culture of living togetherness. The responsible organ in managing the irrigation by employing the bylaws is quite contradicted by the locality. Both the committee and village administration involved in more cases but including water divider and act in combination.

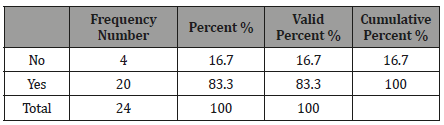

Involvement of female and female heads on equity

Like to male generally female head involved in some events of irrigation water management. They involve in meeting, campaign works and contributing in money for maintenance of the irrigation system (Table 5). However, in a little number of occasions, they fear to take any positions in the water user committee. One of the reasons that does not female involved is also believed by other farmers that the activity is even difficult to male. Similarly, communal irrigation in Tigray (Atsbi Wemberta) and Oromia (Ada’A) districts schemes shows that the participation of female-headed household at forum and leadership is very low [1] (Table 5).

Table 5:Female head household involvement on equity of water.

The information obtained from water user committee shows that special support is not given for female-heads concerning equity. Also, the interview with experts confirmed the same idea raised by WUC. The above problem also shared by Mekuria Tafesse, 2003, that women are not participating, as expected, in irrigation activities. This is mainly because women are mainly engaged (culturally) in household activities such as child rearing, food preparation, water fetching, etc. However, addressing issues relating to gender sensitivity and balance is now a priority in the implementation of community-based projects [2].

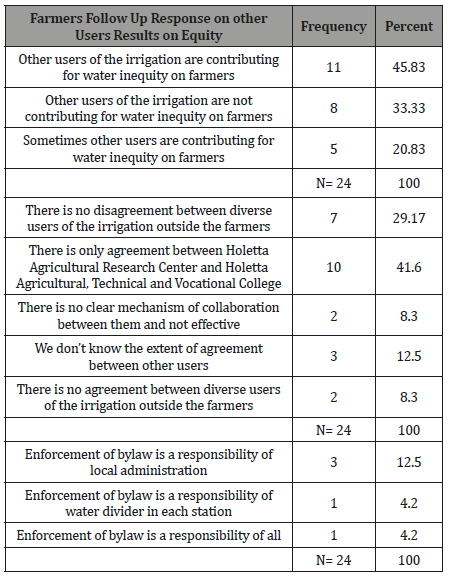

Other users result on equity

As it is states in Water Resources Management Proclamation of Ethiopia domestic use shall have the priority over and above other water uses (Federal democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2000). Consequently, majority of farmers accept all users including government institutions can access to use the river. But its amount and timing have to be accounted not challenging the farmers. Whole of them agreed that investor has to use ground water from the surrounding since they have capacity to exploit available resources. Similarly, a study made by Marrit and Ruerd (2005) in Ethiopia found that irrigation stimulated growth without deepening inequality. However, two irrigation typologies studied on poverty situation in Ethiopia prevails that there was relatively milder among modern irrigation scheme users [15].

Table 6:Other users results on equity of irrigation.

Other users cause water shortage seriously and sometimes slightly. This calls for an investigation to determine a minimum irrigated area that needed to be allotted to a household for sustained poverty reduction and food insecurity eradication [15]. Some of farmers think other users does not cause anything to them. Also, farmers more or less they have agreement with Holetta research centre and some level with Holetta ATVET College regarding with technical support and cost recovery on irrigation water utilization and better management of the irrigation system.

Conclusion

From the study water allocation and distribution is made unequally. These is as the result of misuse of power by water divider and inefficient capacity of the local administration to enable to capable the community to manage the irrigation. Due to this female, female headed and older one affected by this problem. The WUC feel different from surveyed household despite they are hardly to signify who is responsible in managing equitable water allocation and distribution. Majority farmers think that type of the crop under cultivation does not result for the problem of equity. However, experts argue that there is a problem of equity and even farmer crop preference triggered inequity allocation and distribution of irrigation water. Thus, the study revealed that it is a good opportunity to boost a combination of both supplementary and modern irrigation methods to assure equitable sharing of water in dry season.

This community-based irrigation system is also challenged by violation of bylaws among farmers and big conglomerates water users’ affects equity of water use. From the beginning farmers awareness on what the irrigation bylaw said is very law. However, it has a range of penalties to those break water distribution, damage other farmers field, week participation in maintenance and management of the irrigation system. Even though the bylaw place means of implementation their enforcement mechanism is minimal. Also, there is no clear demarcation who should employ the bylaw to the violator from local up to the higher lever as per the legal procedures. On the other hand, without denying female role in minimizing violation, their participation is very low in the irrigation system. Although other water users who has immense capacity are contributing on water inequity and in the future, these will challenge to the livelihoods.

Recommendation

The water sharing principle has to be fixed with farmers land size, crop stage and distance from the primary channel. Those who have large land have to get water by contributing additional cost for the management and utilization of the river. Also, farmers with small lands their interest has to be fulfilled. In the water sharing the committee should include programs that go with crop stage. Not only focusing crop stage but planting perennial crops to those has large lands and annual crops to those who have small lands can be an option. Farming practice directly relate with crops that have high market return related to its cost of irrigation and other inputs are also essential [17]. In water application and timing should be correlated with the crop water demand. To ensure water to farmers that found far from the primary channel should get enough time as compared to others.

The participation of all users is important to improve the management of the river and the irrigation. To overcome this responsible organ has to capacitate the community by training and technical support. Government organ has to work closely with the farmers to increase their production by new technology innovations with integration of farmer prior knowledge of water management. Government should take part in empowering activity involving in the success of community able to fully takeover the irrigation system. But farmers’ decision has to be seen from government and responsible organ for its implications [18].

Female role in the managing and ensuring equity among users need to be seen. From experience and understanding female engage in this activities conflict may be minimized. On the other hand, females are mostly discouraged in farming practices. So, as the main concern the committee should take this as an advantage which female to participate and encouraged.

This present study focuses were farmers in Madda Gudina village. But in the future water demand from different users may come and without go through all users including institutes in the area and others, is not possible to think of equity of the river water. This case study would give insight for wide country level implications. For successful management of community-based irrigation system the government interventions on enabling the community to capture the whole aspects of the irrigations are important.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest

References

- Rahel Deribe (2008) Institutional Analysis of Water Management on Communal. Irrigation Systems in Ethiopia: The Case of Atsbi Wemberta, Tigray Region and Ada’a Woreda, Oromia Region. A Thesis Submitted to Addis Ababa University, School of Graduate Studies, Faculty of Business and Economics.

- Hanibal L, Habtamu Y, Tsedalu J (2008) Analytical Documentation of Traditional Practices and Farmer Innovations in Agricultural Water Management (AWM) in Amhara Region, A case study on two Traditional Irrigation Schemes in North Gondar. Gondar Agricultural Research Center, Gondar, Ethiopia.

- Gall, Le A (2007) Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Irrigation Schemes, the case of Burkaa Alifif, East Hararghe, Ethiopia. Master of Science thesis in Social Water Management and Tropical Agricultural Development.

- Gall, Le A (2007) Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Irrigation Schemes, the case of Burkaa Alifif, East Hararghe, Ethiopia. Master of Science thesis in Social Water Management and Tropical Agricultural Development.

- Holetta Genet Multimedia Information (2010) Internet document.

- Holetta Town Administration (2010) Holetta Small Scale Irrigation Projects, March 2009.

- Sommer B, Sommer R (1997) A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research: Tools and Techniques. Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, USA.

- Kaplan B, Duchon D (1988) Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Information Systems Research: A Case Study. This paper was presented at the Ninth Annual International Conference on Information Systems, Minneapolis, MN, and November 30-December 3, 1988.

- Berehanu Hailu (2009) The Impact of Agricultural Policies on Smallholder Innovation Capacities. The Case of Household Level Irrigation Development in Two Communities of Kilte Awlaelo Woreda, Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis in Communication and Innovation Studies Group, Department of Social Science, Wageningen University, Netherlands.

- Darout Gum (2004) The Socio-Cultural Aspects of Irrigation Management: The Case of Small-Scale Irrigation Schemes in the Upper Tekeze Basin, Tigray Region. A Thesis Submitted to Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Institute of Regional and Local Development Studies.

- FAO (1998) Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for computing crop water requirements. Food and Agricultural Organization. Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56. Rome, Italy.

- Geremew EB (2008) Modeling the Soil Water Balance to Improve Irrigation Management of Traditional Irrigation Schemes in Ethiopia. PhD Dissertation in Agronomy, Department of Plant Production and Soil Science, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

- Bello WB (2008) The Effect of Rain-Fed and Supplementary Irrigation on the Yield and Yield Components of Maize in Mekelle, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 1(2): 1-7.

- Getamesay Shiwenzu (2017) Study of scientific and traditional irrigation water management practices in Holeta River Catchment in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies & Management 10(8): 1022-1033.

- Namara RE, Makombe G, Hogose F, Awulachwe SB (2007) Rural Poverty & Inequality in Ethiopia: Can irrigation make a difference. IIPE Workshop, 27-29 Nov, 2007, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Internet document (2010)

- Mekuria Tafesse (2003) Small-Scale Irrigation for Food Security in Sub- Saharan 20–29 January 2003, CTA Working Document Number 8031. Organised CTA with the support of Tigray Water Resources Development Bureau, Ethiopia, Published and printed by: The ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA). Africa Report and Recommendations of a CTA study visit in Ethiopia.

- Haile Tesfay (2008) Impact of Irrigation Development on Poverty Reduction in Northern Ethiopia. A thesis presented to the Department of Food Business and Development in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, National University of Ireland, and Cork, Ireland.

- Renaualt, D, Hemakumara M, Molden D (2001) Impacts of Water Consumption by Perennial Vegetation in Irrigated Areas of the humid Tropics. A case for Rethinking Traditional Values of Irrigation Design, Management and Performance Assessment, Annual Report 2000-2001. Improving Water and Land Resource Management for Food, Livelihoods.

- Schell C (1992) The Value of the Case Study as a Research Strategy. Manchester, Manchester Business School, England.Lemma Dinku (2004) Smallholders’ Irrigation Practices and Issues of Community Management: The Case of Two Irrigation Systems in Eastern Oromia, Ethiopia. A Thesis Submitted to Addis Ababa University, School of Graduate Studies. Institute of Regional and Local Development Studies.

- Holetta Town Administration. Annual Plan. 2010/2011.

-

Getamesay Shiwenzu. Rethinking Traditional Irrigation Water Equity in Holetta River, Awash River Basin, Ethiopia. Sci J Research & Rev. 1(5): 2019. SJRR.MS.ID.000525.

Platelet, Neonatal sepsis, Mean platelet volume, Pathogenic bacterium, Hypothermia, Hyperthermia, Bradycardia, Tachycardia, Poor perfusion, Hypotension, Chromosomal abnormalities

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.