Review Article

Review Article

Somatic Tinnitus and Manual Therapy: A Systematic Review

Bonni Lynn Kinne*, Linnea Christine Bays, Kara Lynne Fahlen and Jillian Sue Owens

Department of Physical Therapy, Grand Valley State University, USA

Bonni Lynn Kinne, Department of Physical Therapy, Grand Valley State University, USA.

Received Date: December 14, 2018; Published Date: February 04, 2019

Abstract

Background: In 2016, a systematic review was conducted to examine the effects of physical therapy interventions on individuals with subjective tinnitus. However, the research study investigated subjective tinnitus that may not have had a somatic origin. In addition, only one of the included studies specifically assessed the effectiveness of manual therapy. Objectives: The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effects of manual therapy techniques on individuals with somatic tinnitus.

Methods: A search was performed using the following databases: CINAHL Complete, ProQuest Medical Library, and PubMed. The search terms were “somatic tinnitus” OR “somatosensory tinnitus” AND “manual therapy”. An evaluation of the evidence level for each included article was conducted using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence, and an evaluation of the methodological rigor for each included article was conducted using criteria adapted by Medlicott and Harris.

Results: A qualitative synthesis was ultimately performed on eight articles. The manual therapy techniques included in this systematic review were cervical mobilizations, myofascial techniques, osteopathic manipulations, soft tissue techniques, and manual therapy as developed by the School of Manual Therapy Utrecht. This systematic review also included complementary treatment approaches such as patient education, therapeutic exercise, transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation, and home exercise programs.

Conclusion: Manual therapy appears to be an effective intervention for individuals with somatic tinnitus, especially if they have co-varying tinnitus or tinnitus sensitization. In addition, a multimodal intervention approach may be the ideal way in which to positively impact an individual’s activities of daily living.

Keywords: Manual therapy; Somatic; Somatosensory; Systematic review; Tinnitus

Introduction

Tinnitus is “the perception of sound for which there is no acoustic source external to the head.” [1] The sound associated with tinnitus is most often described as a buzzing, clicking, pulsating, and/or ringing sensation [2]. Tinnitus affects approximately 50 million adults in the United States alone [3]. Although Nondahl et al. [4] discovered that the prevalence of tinnitus was approximately 10%, tinnitus prevalence was found to be over 30% in another research study [5]. Gender does not appear to be directly correlated with the prevalence of tinnitus [6]. However, tinnitus more frequently occurs in older adults and in non-Hispanic Caucasians than in any other groups of individuals [3]. Some of the characteristic risk factors associated with the development of tinnitus include arteriosclerosis, arthritis, dizziness, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, head trauma, noise exposure, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories [3,4,6,7]. The presence of tinnitus tends to have a negative effect upon an individual’s quality of life [6]. Two recent research studies [8,9] reported that individuals with tinnitus often experience concomitant psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression. In addition, insomnia accompanies the tinnitus symptoms in more than half of all individuals with this medical condition [10].

There are several different ways in which tinnitus is classified [2]. Three classification systems include (1) primary tinnitus (idiopathic in nature) vs. secondary tinnitus (related to a known medical issue), (2) recent onset tinnitus (a duration of less than 6 months) vs. persistent tinnitus (a duration of 6 months or more), and (3) bothersome tinnitus (one’s quality of life is negatively affected) vs. non-bothersome tinnitus (one’s quality of life is not affected). Tinnitus may also be described as objective or subjective [11]. Objective tinnitus is able to be detected by the individual with the medical condition as well as by other individuals through the use of a stethoscope. This extremely rare type of tinnitus is caused by an auditory sensation generated within the body. Subjective tinnitus, on the other hand, is only able to be detected by the individual with the medical condition. This more common type of tinnitus is usually related to a peripheral and/or central auditory system disorder. One type of subjective tinnitus is somatic tinnitus.

Although most cases of tinnitus are caused by ear pathology, somatic tinnitus is related to a head and/or neck disorder [12]. The diagnosis of this type of tinnitus is dependent upon the presence of one or more of the following criteria: (1) an injury to the head/neck, (2) tinnitus following the performance of a head/neck manipulation, (3) pain associated with the head/neck, (4) tinnitus following the onset of the head/neck pain, (5) an exacerbation of the tinnitus due to poor posture of the head/neck, and/or (6) severe grinding of the teeth. Researchers have proposed that a connection between the somatosensory system and the auditory system in the region of the dorsal cochlear nucleus is the physiologic mechanism that results in somatic tinnitus [13]. Because of this proposed connection, a tinnitus evaluation should include a comprehensive assessment of the head and neck as well as somatic testing procedures [14]. Somatic testing involves a series of active or resisted extremity, cervical, and temporomandibular movements as well as applied pressure to the head and neck musculature. If any of these assessment procedures increase the intensity of the tinnitus, somatic tinnitus should be suspected. The primary treatment objective in suspected cases of somatic tinnitus is to decrease muscular tightness in the cervical region and in the temporomandibular joint [12,14]. Some of the interventions that have been suggested to achieve this objective are acupuncture treatments, bite splints, cognitive therapy, electrical stimulation, postural education, relaxation techniques, steroid injections, stretching activities, and therapeutic exercise. Manual therapy has also been proposed. However, “as much as [manual therapy] has been receiving more attention in the current literature, it still needs further clarification” [12].

In 2016, a systematic review [15] was conducted to examine the effects of physical therapy interventions on individuals with subjective tinnitus. However, the research study investigated subjective tinnitus that may not have had a somatic origin. In addition, only one of the included studies specifically assessed the effectiveness of manual therapy. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effects of manual therapy techniques on individuals with somatic tinnitus.

Methods

Databases and search terms

A search was performed using the following databases: CINAHL Complete, ProQuest Medical Library, and PubMed. The search terms were “somatic tinnitus” OR “somatosensory tinnitus” AND “manual therapy”. The Cochrane Library was searched to confirm that no previously published systematic reviews had examined the effects of manual therapy on individuals with somatic tinnitus. Studies written in languages other than English were excluded. Therefore, a language bias was potentially introduced.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were comprised of (1) individuals, 18 years of age and older, who had somatic tinnitus; (2) manual therapy as a component of the intervention; (3) other types of therapy or no therapy as the comparison intervention if applicable; (4) valid and reliable tinnitus-specific outcome measures; and (5) studies other than those that used mechanism-based reasoning. The exclusion criteria were comprised of (1) individuals without somatic tinnitus; (2) individuals under the age of 18; (3) no use of manual therapy in the intervention; (4) no use of valid and reliable tinnitus-specific outcome measures; and (5) studies that used mechanism-based reasoning.

Evidence level

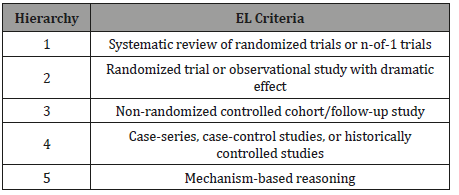

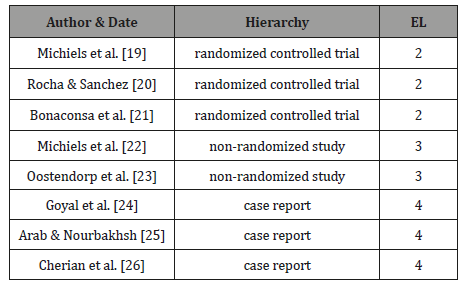

An evaluation of the evidence level for each included article was conducted using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence (Table 1) [16]. The highest level of evidence is level one, and the lowest level of evidence is level five. An independent evaluation of the articles was conducted by each of the four authors to minimize the risk of bias. Any conflicting opinions between the authors were discussed until a unanimous agreement was reached (Table 1).

Table 1: Evidence Level (EL) overview [16].

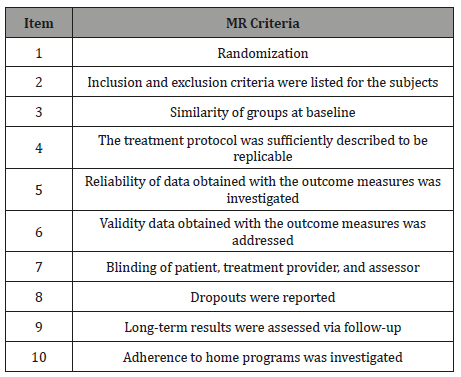

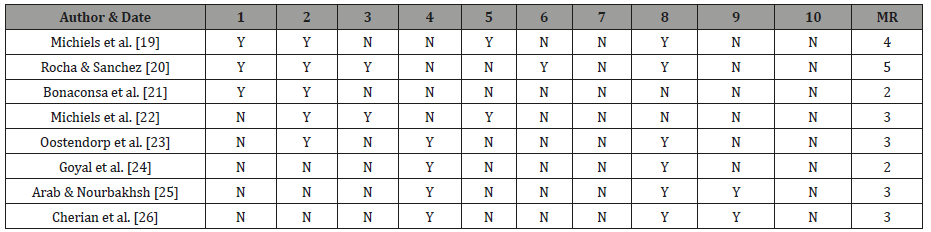

Methodological rigor

An evaluation of the methodological rigor for each included article was conducted using criteria adapted by Medlicott and Harris (Table 2) [17]. This methodological rigor evaluation tool contains 10 items. A point is awarded for an item when the criterion for that particular item is clearly met. The methodological rigor of a study is considered “strong” with a score of 8 to 10, “moderate” with a score of 6 to 7, and “weak” with a score less than or equal to 5. An independent evaluation of the articles was conducted by each of the four authors to minimize the risk of bias. Any conflicting opinions between the authors were discussed until a unanimous agreement was reached (Table 2).

Table 2: Methodological Rigor (MR) overview [17].

Results

Search strategy

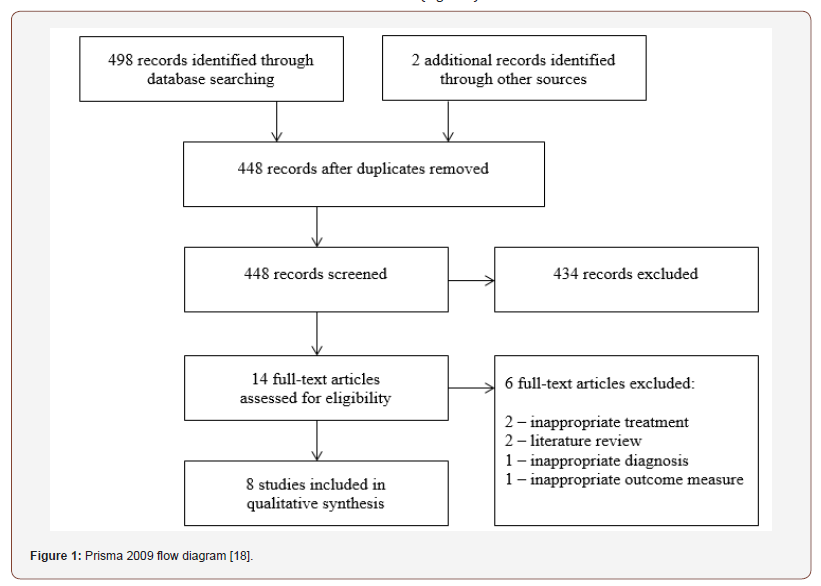

As shown in the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram (Figure 1), [18] an online database search identified 498 articles. Other sources identified two additional articles. Following the elimination of duplicates, 448 article titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. The 14 full-text articles that resulted from the previous step were assessed for eligibility to determine if the inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. A qualitative synthesis was then performed on the eight articles [19-26] that met these criteria (Figure 1).

Evidence level

The 2011 Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Guide [16] was used to identify the evidence level of the eight included research articles. Three studies [19-21] were randomized controlled trials, level 2 evidence. Two studies [22-23] were nonrandomized studies, level 3 evidence. Finally, there were three case reports, [24-26] level 4 evidence (Table 3).

Table 3: Evidence Level (EL) results [16].

Methodological rigor

The methodological rigor was assessed using the adapted Medlicott and Harris scale, [17] and the scores ranged from 2 to 5 for each of the eight studies (Table 4). One study [20] was given a score of 5, one study [19] was given a score of 4, four studies [22,23,25,26] were given a score of 3, and two studies [21,24] were given a score of 2. All of the studies had scores less than or equal to 5, indicating weak methodological rigor (Table 4).

Table 4: Methodological Rigor (MR) results [17].

Item 1 = randomization; Item 2 = inclusion and exclusion criteria were listed for the subjects; Item 3 = similarity of groups at baseline; Item 4 = the treatment protocol was sufficiently described to be replicable; Item 5 = reliability of data obtained with the outcome measures was investigated; Item 6 = validity data obtained with the outcome measures was addressed; Item 7 = blinding of patient, treatment provider, and assessor; Item 8 = dropouts were reported; Item 9 = long-term results were assessed via follow-up; Item 10 = adherence to home programs was investigated.

Summary of Studies

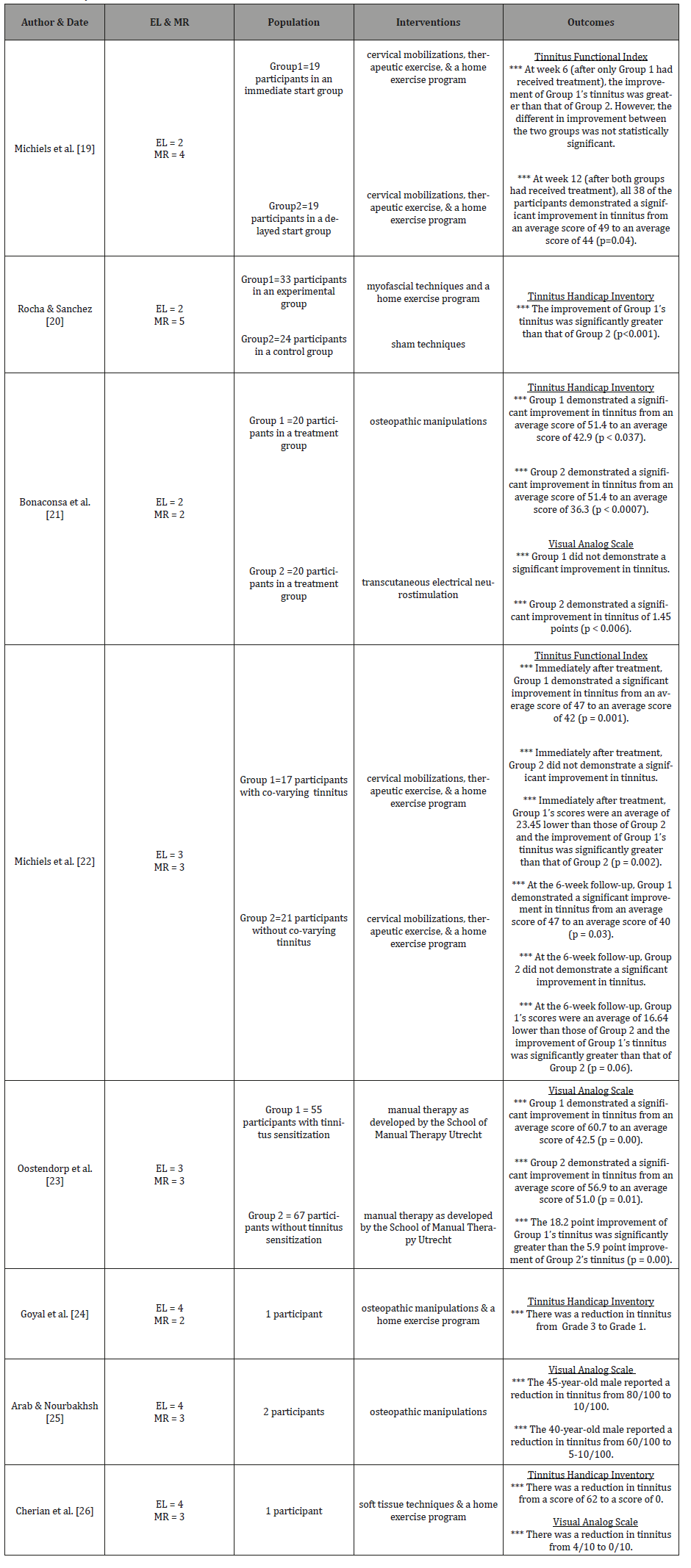

The evidence level, methodological rigor, population, interventions, and outcomes of the eight studies [19-26] are outlined in Table 5 (Table 5).

Table 5: Summary of Studies.

The study by Michiels et al. [19] was a randomized controlled trial. The authors included 38 participants with somatic tinnitus. Nineteen of the participants were randomly assigned to an immediate start group, and 19 of the participants were randomly assigned to a delayed start group. All of the participants received cervical mobilizations, therapeutic exercise, and a home exercise program. The prescribed treatment was 12 sessions over a 6-week period. The immediate start group began treatment at baseline, and the delayed start group began treatment at week 6. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measure was the Tinnitus Functional Index [27]. The Tinnitus Functional Index is a 25-item questionnaire that measures the severity and negative impact of an individual’s tinnitus. Table 3 outlines the results of this randomized controlled trial..

The study by Rocha and Sanchez [20] was a randomized controlled trial. The authors included 57 participants with somatic tinnitus. Thirty-three of the participants were randomly assigned to an experimental group, and 24 of the participants were randomly assigned to a control group. The experimental group received myofascial techniques and a home exercise program, and the control group received sham techniques. The prescribed treatment was 10 sessions over a 10-week period. The primary tinnitusspecific outcome measure was the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [28]. The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory is a 25-item questionnaire that includes functional, emotional, and catastrophic subscales. The total score is then sometimes categorized from Grade 1 to Grade 5 with lower scores indicating less tinnitus and higher scores indicating more tinnitus. Table 3 outlines the results of this randomized controlled trial.

The study by Bonaconsa et al. [21] was a randomized controlled trial. The authors included 40 participants with somatic tinnitus. Twenty participants were randomly assigned to each of two treatment groups. One treatment group received osteopathic manipulations, and the other treatment group received transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation. The prescribed treatment was 8 to 10 sessions over a 2-month period. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measures were the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [28] and a visual analog scale [29] that evaluated tinnitus from 1 (least) to 10 (worst). The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory was described in the Rocha and Sanchez [20] paragraph. Table 3 outlines the results of this randomized controlled trial.

The study by Michiels et al. [22] was a non-randomized study. The authors included 38 participants with somatic tinnitus. Seventeen of the participants had co-varying tinnitus, and 21 of the participants did not. All of the participants received cervical mobilizations, therapeutic exercise, and a home exercise program. The prescribed treatment was 12 sessions over a 6-week period. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measure was the Tinnitus Functional Index [27]. The Tinnitus Functional Index was described in the Michiels et al. [19] paragraph. Table 3 outlines the results of this non-randomized study.

The study by Oostendorp et al. [23] was a non-randomized study. The authors included 122 participants with somatic tinnitus. Fifty-five of the participants had tinnitus sensitization, and 67 of the participants did not. All of the participants received manual therapy as developed by the School of Manual Therapy Utrecht. The prescribed treatment was 6 to 12 sessions over a 12-week period. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measure was a visual analog scale [29] that evaluated tinnitus from 0 (none) to 100 (worst). Table 3 outlines the results of this non-randomized study.

The study by Goyal et al. [24] was a case report. The authors included a 30-year-old female with somatic tinnitus. The participant received osteopathic manipulations and a home exercise program. The prescribed treatment was three sessions over a 3-week period. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measure was the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [28]. The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory was described in the Rocha and Sanchez [20] paragraph. Table 3 outlines the results of this case report.

The study by Arab and Nourbakhsh [25] was a case report. The authors included two males, ages 45 and 40, with somatic tinnitus. The participants each received osteopathic manipulations. The prescribed treatment was five sessions over a 2- to 3-week period. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measure was a visual analog scale [29] that evaluated tinnitus from 1 (least) to 100 (worst). Table 3 outlines the results of this case report.

The study by Cherian et al. [26] was a case report. The authors included a 42-year-old male with somatic tinnitus. The participant received soft tissue techniques and a home exercise program. The prescribed treatment was 10 sessions over a 10-week period. The primary tinnitus-specific outcome measures were the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [28] and a visual analog scale [29] that evaluated tinnitus from 0 (none) to 10 (worst). The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory was described in the Rocha and Sanchez [20] paragraph. Table 3 outlines the results of this case report.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effects of manual therapy techniques on individuals with somatic tinnitus. A qualitative synthesis was performed on eight articles [19-26] that met the inclusion criteria.

Three case reports [24-26] discovered that manual therapy was generally effective for individuals with somatic tinnitus. In the Goyal et al. [24] study, there was a reduction in tinnitus scores on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [28] following a manual therapy intervention of osteopathic manipulations and a home exercise program. In the Arab and Norbakhsh [25] study, the two participants reported a reduction in their tinnitus scores using a visual analog scale [29] following a manual therapy intervention of osteopathic manipulations. Finally, in the Cherian et al. [26] study, there was a reduction in tinnitus scores on both the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [28] and a visual analog scale [29] following a manual therapy intervention of soft tissue techniques and a home exercise program.

Although case reports are inherently limited in terms of providing a cause-and-effect relationship between an intervention and an outcome, three randomized controlled trials [19-21] were included in this systematic review. In the Michiels et al. [19] study, the tinnitus improvement of the immediate start group that received manual therapy techniques during the first 6 weeks of the investigation was greater than the tinnitus improvement of the delayed start group that did not receive manual therapy techniques during this 6-week time frame. In addition, after the delayed start group had received manual therapy techniques during the second 6 weeks of the investigation, all of the participants in the study demonstrated a significant improvement in their tinnitus. In the Rocha and Sanchez [20] study, the tinnitus improvement of the experimental group that received legitimate manual therapy techniques was significantly greater than the tinnitus improvement of the control group that received sham techniques. Finally, in the Bonaconsa et al. [21] study, the treatment group that received transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation generally demonstrated greater improvements in tinnitus than did the treatment group that received manual therapy techniques. However, the manual therapy group’s tinnitus scores were still lower at the end of the investigation than they were at the beginning of the investigation. Because randomized controlled trials are considered the gold standard of experimental designs, the results of these three randomized controlled trials [19-21] support the outcomes of the three case reports [24-26] and suggest a causal relationship between the use of manual therapy and the reduction in somatic tinnitus.

In addition to the three case reports [24-26] and the three randomized controlled trials [19-21] just described, this systematic review also included two non-randomized studies [22-23]. In the Michiels et al. [22] study, the authors provided manual therapy techniques to two groups of participants, one group with covarying tinnitus and one group without. Co-varying tinnitus is a situation in which individuals report that their tinnitus and cervical pain are directly related [12]. The interventions used in this study [22] included cervical mobilizations, therapeutic exercise, and a home exercise program. The results of this study demonstrated that the improvement of the participants with co-varying tinnitus was significantly greater than the improvement of the participants without co-varying tinnitus. This outcome is not surprising because somatic tinnitus is a type of subjective tinnitus related to a head and/or neck disorder [12]. Therefore, if a therapist is able to successfully decrease muscular tightness in the cervical region and/or the temporomandibular joint, the expectation is that patients will report a concurrent decrease in their tinnitus [14]. In the Oostendorp et al. [23] study, the authors provided manual therapy techniques to two groups of participants, one group with tinnitus sensitization and one group without. Tinnitus sensitization is a situation in which individuals report a heightened awareness of their tinnitus that leads to feelings of fear and helplessness [30]. The interventions used in this study [23] included manual therapy as developed by the School of Manual Therapy Utrecht, a treatment method that includes an educational component. The results of this study demonstrated that the improvement of the participants with tinnitus sensitization was significantly greater than the improvement of the participants without tinnitus sensitization. A recent theoretical concept journal publication proposed that the underlying cause of tinnitus sensitization is closely related to that of pain sensitization [31]. Therefore, Oostendorp et al. [23] concluded that “a more cognitive-oriented treatment (transition to information-based advice and explanation on tinnitus), combined with manual therapeutic treatment on the level of impairments in physiological functions (transition to somatosensory functions), may be effective in reducing pain-related fear (transition to tinnitusrelated fear).” In other words, a combination of manual therapy and tinnitus education may be the most effective way in which to treat individuals with somatic tinnitus, especially if tinnitus sensitization is present.

In addition to manual therapy techniques, several other interventions have been recommended for somatic tinnitus [12,14]. In a 2011 randomized controlled trial, [32] 27 participants received acupuncture treatments (the experimental group) and 27 participants received placebo treatments (the control group). In a 2008 randomized controlled trial, [33] 63 participants received cognitive therapy (the experimental group) and 67 participants were placed on a waiting list (the control group). In a 2016 randomized controlled trial, [34] 20 participants received steroid injections (the experimental group) and 20 participants received saline injections (the control group). Finally, a 2010 randomized controlled trial [35] examined the effects of Qigong (an intervention that incorporates postural education, relaxation techniques, stretching activities, and therapeutic exercise) on somatic tinnitus. In this study, 40 participants received Qigong (the experimental group) and 40 participants were placed on a waiting list (the control group). The outcomes of all of these studies demonstrated that the tinnitus improvement of the participants in the experimental groups was significantly greater than that of the participants in the control groups. In addition, electrical stimulation was found to be generally more effective than manual therapy in the Bonaconsa et al. [21] study. Although bite splints may also be a valid treatment modality, [12,14] no recent randomized controlled trials have examined the relationship between the use of bite splints and the improvement of somatic tinnitus.

Strengths and limitations of the systematic review

The following strengths were identified in this systematic review: (1) no similar study had been previously published; (2) the risk of bias was minimized because all four authors actively participated in the evidence level and methodological rigor methods; and (3) several manual therapy techniques were identified for their possible use in clinical practice. The following limitations were identified in this systematic review: (1) only three of the eight studies [19-21] were randomized controlled trials; (2) the methodological rigor of all eight studies [19-26] was classified as “weak”; (3) only two of the eight studies [25-26] provided longterm follow-up results; and (4) because studies written in languages other than English were excluded, a language bias was potentially introduced.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Manual therapy appears to be an effective intervention for individuals with somatic tinnitus, especially if they have covarying tinnitus or tinnitus sensitization. The manual therapy techniques included in this systematic review were cervical mobilizations, [19,22] myofascial techniques, [20] osteopathic manipulations, [21,24,25] soft tissue techniques, [26] and manual therapy as developed by the School of Manual Therapy Utrecht [23]. This systematic review also included complementary treatment approaches such as patient education, [23] therapeutic exercise,[19,22] transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation, [21] and home exercise programs [19,20,22,24,26].

Future research should include randomized controlled trials with high methodological rigor. These randomized controlled trials should compare one type of manual therapy technique vs. another type of manual therapy technique or compare a manual therapy technique combined with a complementary treatment approach vs. the manual therapy technique alone. In addition, it is important that future investigations include a long-term follow-up as well as monitor home exercise program compliance.

Conclusion

Tinnitus affects approximately 50 million adults in the United States alone, [3] and the presence of tinnitus tends to have a negative effect upon an individual’s quality of life [6]. Although most cases of tinnitus are caused by ear pathology, somatic tinnitus is related to a head and/or neck disorder [12]. The primary treatment objective in suspected cases of somatic tinnitus is to decrease muscular tightness in the cervical region and in the temporomandibular joint [12,14]. This systematic review found that manual therapy appears to be an effective intervention for individuals with somatic tinnitus, especially if they have co-varying tinnitus or tinnitus sensitization. The manual therapy techniques included in this systematic review were cervical mobilizations, [19,22] myofascial techniques, [20] osteopathic manipulations, [21,24,25] soft tissue techniques, [26] and manual therapy as developed by the School of Manual Therapy Utrecht [23]. In addition to manual therapy techniques, several other interventions have been recommended for somatic tinnitus [12,14]. Therefore, a multimodal intervention approach may be the ideal way in which to positively impact an individual’s activities of daily living.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Henry JA, Dennis KC, Schechter MA (2005) General review of tinnitus: prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J Speech Lang Hear Res 48(5): 1204-35.

- Tunkel DE, Bauer CA, Sun GH, Rosenfeld RM, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. (2014) Clinical practice guideline: tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 151(2): S1-S40.

- Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR (2010) Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med 123(8): 711-718.

- Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang GH, Klein BEK, Klein R, et al. (2011) Tinnitus and its risk factors in the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Int J Audiol 50(5): 313-320.

- Sindhusake D, Mitchell P, Newall P, Golding M, Rochtchina E, et al. (2003) Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus in older adults: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int J Audiol 42(5): 289-294.

- Negrila Mezei A, Enache R, Sarafoleanu C (2011) Tinnitus in elderly population: clinical correlations and impact upon QoL. J Med Life 4(4): 412-416.

- Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Klein BEK, Klein R, et al. (2010) The ten-year incidence of tinnitus among older adults. Int J Audiol 49(8): 580-585.

- Belli S, Belli H, Bahcebasi T, Ozcetin A, Alpay E, et al. (2008) Assessment of psychopathological aspects and psychiatric comorbidities in patients affected by tinnitus. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 265(3): 279-285.

- Zoger S, Svedlund J, Holgers KM (2006) Relationship between tinnitus severity and psychiatric disorders. Psychosomatics 47(4): 282-288.

- Lasisi AO, Gureje O (2011) Prevalence of insomnia and impact on quality of life among community elderly subjects with tinnitus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 120(4): 226-230.

- Moller AR. (2003) Pathophysiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 36: 249-266.

- Sanchez TG, Rocha CB (2011) Diagnosis and management of somatosensory tinnitus: review article. Clinics 66(6): 1089-1094.

- Levine RA, Abel M, Cheng H (2003) CNS somatosensory-auditory interactions elicit or modulate tinnitus. Exp Brain Res 153(4): 643-648.

- Haider HF, Hoare DJ, Costa RFP, Potgieter I, Kikidis D, et al. (2017) Pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of somatosensory tinnitus: a scoping review. Front Neurosci 11: 1-8.

- Michiels S, Naessens S, Van de Heyning P, Braem M, Visscher CM, et al. (2016) The effect of physical therapy treatment in patients with subjective tinnitus: a systematic review. Front Neurosci 10: 1-8.

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2011) Levels of Evidence. Oxford, England.

- Medlicott MS, Harris SR (2006) A systematic review of the effectiveness of exercise, manual therapy, electrotherapy, relaxation training, and biofeedback in the management of temporomandibular disorder. Phys Ther 86(7): 955-973.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151: 264-269.

- Michiels S, Van de Heyning P, Truijen S, Hallemans A, De Hertogh W (2016) Does multi-modal cervical physical therapy improve tinnitus in patients with cervicogenic somatic tinnitus? Man Ther 26: 125-131.

- Rocha CB, Sanchez TG (2012) Efficacy of myofascial trigger point deactivation for tinnitus control. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 78(6): 21-26.

- Bonaconsa A, Mazzoli M, Magnano SLA, Milanesi C, Babighian G (2010) Posturography measures and efficacy of different physical treatments in somatic tinnitus. Int Tinnitus J 16(1): 44-50.

- Michiels S, Van de Heyning P, Truijen S, Hallemans A, De Hertogh W (2017) Prognostic indicators for decrease in tinnitus severity after cervical physical therapy in patients with cervicogenic somatic tinnitus. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 29: 33-37.

- Oostendorp RAB, Bakker I, Elvers H, Mikolajewska E, Michiels S, et al. (2016) Cervicogenic somatosensory tinnitus: an indication for manual therapy plus education? Part 2: a pilot study. Man Ther 23: 106-113.

- Goyal M, Sharma S, Baisakhiya N, Goyal K (2017) Efficacy of an eccentric osteopathic manipulation treatment in somatic tinnitus. Indian J Otol 23: 125-128.

- Arab AM, Nourbakhsh MR (2014) The effect of cranial osteopathic manual therapy on somatic tinnitus in individuals without otic pathology: two case reports with one year follow up. Int J Osteopath Med 17(2): 123-128.

- Cherian K, Cherian N, Cook C, Kaltenbach JA (2013) Improving tinnitus with mechanical treatment of the cervical spine and jaw. J Am Acad Audiol 24(7): 544-555.

- Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, Stewart BJ, Abrams HB, et al. (2012) The Tinnitus Functional Index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear 33(2): 153-176.

- Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB (1996) Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122(2):143-148.

- Adamchic I, Langguth B, Hauptmann C, Tass PA (2012) Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. Am J Audiol 21(2): 215-225.

- Zenner HP, Pfister M, Birbaumer N (2006) Tinnitus sensitization: sensory and psychophysiological aspects of a new pathway of acquired centralization of chronic tinnitus. Otol Neurotol 27(8): 1054-1063.

- Oostendorp RAB, Bakker I, Elvers H, Mikolajewska E, Michiels S, et al. (2016) Cervicogenic somatosensory tinnitus: an indication for manual therapy? Part 1: theoretical concept. Man Ther 23: 120-123.

- Rogha M, Rezvani M, Khodami AR (2011) The effects of acupuncture on the inner ear originated tinnitus. J Res Med Sci 16(9): 1217-1223.

- Weise C, Heinecke K, Rief W (2008) Biofeedback-based behavioral treatment of chronic tinnitus: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 76(6): 1046-1057.

- Elzayat S, El-Sherif H, Hegazy H, Gabr T, El-Tahan AR (2016) Tinnitus: evaluation of intratympanic injection of combined lidocaine and corticosteroids. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 78(3): 159-166.

- Biesinger E, Kipman U, Schatz S, Langguth B (2010) Qigong for the treatment of tinnitus: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Psychosom Res 69(3): 299-304.

-

Bonni Lynn Kinn, Linnea Christine Bays, Kara Lynne Fahlen, Jillian Sue Owens. Somatic Tinnitus and Manual Therapy: A Systematic Review. 1(2): 2019. OJOR.MS.ID.000510.

-

Somatic Tinnitus, Manual Therapy, Physical Therapy, Somatic Origin, Cervical Mobilizations, Myofascial Techniques, Osteopathic Manipulations, Soft Tissue Techniques, Therapeutic Exercise, Transcutaneous Electrical Neurostimulation, Somatosensory, Systematic Review, Tinnitus Sensitization, Buzzing, Clicking, Pulsating, Arteriosclerosis, Arthritis, Dizziness, Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Head Trauma, Noise Exposure, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories, Anxiety, Depression, Ear Pathology, Head Manipulation, Neck Manipulation, Physiologic Mechanism.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.