Research Article

Research Article

Impact of Mastoidectomy in the Repair of Tympanic Perforation in Patients with Chronic Non- Cholesteatomatous Otitis Media with Sclerotic Mastoid Bone

González Quintana J1, Lugo Machado JA2*, Martínez Villa FA3, Portillo Flores JA1 and Rubio Espinoza A1

1Department of Otolaryngology and head and neck surgery, Mexican Institute of Social Security, Mexico

2Department of Otolaryngology, Mexican Social Security Institute Cd Obregón, Mexico

3Hospital of Family Medicine, Mexican Institute of Social Security, Mexico

Lugo Machado JA, Department of Otolaryngology, Mexican Institute of Social Security Prolongación Hidalgo y Sahuaripa S/N Colonia Bellavista, Cajeme, 85130, Cd Obregón, Sonora, Mexico.

Received Date: June 12, 2019; Published Date: June 21, 2019

Abstract

Objective: To describe the clinical characteristics and results obtained in patients who underwent repair of tympanic perforation secondary to chronic non-cholesteatomatous otitis media with sclerotic mastoid bone, with and without mastoidectomy.

Material and methods: comparative cross-sectional study, with a non-probabilistic sampling by consecutive series of cases. We reviewed the files of patients who meet the inclusion criteria in the period from January 2015 to May 2016. Data was collected such as; age, sex, state of origin, history of smoking, cause of perforation, duration of dry ear, data to otoscopy, presence of trans operative and postoperative otorrhea, state of the mucosa, presence of tympanosclerosis or miringoesclerosis, perforation or retraction of the graft.

Results: A total of 48 patients were selected; 31 of the female sex and 17 of the male sex, with an average age of 43.25 years, the follow-up was 3 months. When comparing the group of patients with and without mastoidectomy, no statistically significant difference was found in the success of the surgery (graft perforation RR 1.2, p 1, postoperative otorrhea RR 2.26, p 0.68 and graft retraction RR 0.76, p 1). We found that the characteristics during and before surgery did not influence the final result, presenting an overall average of 94% of graft integration.

Conclusion: The mastoidectomy shows no additional benefit in tympanic membrane repair, the characteristics during and prior to surgery did not influence the final result.

Keywords: Chronic otitis media; Mastoidectomy; Tympanoplasty

Introduction

According to the time of evolution, otitis media is subdivided into; Acute when the process lasts less than 3 weeks. Subacute when the infection lasts from 3 weeks to 3 months and Chronic when the disease lasts for more than 3 months [1]. Chronic otitis media is an insidious, slow-moving mucoperiosteal inflammatory process that affects the structures of the middle ear cavity, mastoid cells and eustachian tube1. It may precede suppurative processes and affect the tympanic membrane with perforation or scarring (neotimpano or tympanosclerosis) and even with osteolytic lesions. According to clinical findings, chronic otitis media is classified as cholesteatomatous or non-cholesteatomatous [1].

The chronic cholesteatomatous otitis media can be

a. Congenital, which is less frequent, it is diagnosed when there is embryogenic residue of scaly tissue in the tympanic cavity.

b. Acquired, which in turn can be primary or secondary [1].

Tympanic perforation can have other etiologies besides the infectious one, such as traumatic, neoplastic or iatrogenic defects and in turn the perforation sites can be marginal or central, whose nomination depends on the existence or not of peripheral remnant at the site of the perforation [2,3]. Chronic otitis media is a disease frequently seen throughout the world, it is not known exactly the incidence of this entity in the general population, it is estimated that 0.5% of people over 15 suffer from any of its forms suppurative, and around 4% some type of tympanic perforation, the distribution between sexes and ages (in the adult stage) is apparently homogeneous1. Malnutrition, lack of hygiene, poor housing, and high population density are factors that are associated with a higher incidence of middle ear infections [4].

Although the incidence of the disease and its complications have decreased due to the widespread use of antibacterial agents, in order to completely cure the disease, surgical means are necessary in some cases [1,5]. However, the surgical treatment of chronic non-cholesteatomatous otitis media is still controversial, it is well accepted that the main objective of the operation is to obtain a permanently dry ear and close the perforation, with other objectives being to remove the pathological tissues, restore the normal functions of the middle ear and eradicate the disease from the mastoid cells [5,6]. Tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy has been identified as an effective method for the treatment of chronic ear infection resistant to antibiotic treatment, but the effect of mastoidectomy in patients no evidence of active infectious disease remains highly debated and unproven [6]. Some of the indications for mastoidectomy are the eradication of chronic infection and as an approach for various neuro- logical procedures [6].

Mastoidectomy was first described by Louis Petit in the 1700s, although the concept did not gain acceptance until 1958, with cortical mastoidectomy popularized by William House [6]. Tympanoplasty is a common surgical procedure to close the perforations of the tympanic membrane [7]. The main objectives of tympanoplasty are to obtain a stable intact tympanic membrane, eradicate middle ear disease and to improve hearing [7]. The modern tympanoplasty was introduced in 1950 by Zollner and Wullstein, since then, different techniques were developed for the repair of the tympanic membrane, being Tabb and Shea who performed the first medial placement of the graft in reference to the hammer and the rest of the membrane tympanic [2]. The results of tympanic membrane repair, although generally favorable, can vary significantly depending on multiple factors, including age, active infection at the time of surgery, eustachian tube dysfunction, variations in surgical technique. , the size and location of the perforation; cause of the perforation, the condition of the ossicular chain and the mucous membrane of the middle ear, the condition of the contralateral ear, the experience of the surgeon, the duration of the dry ear period prior to surgery, smoking and the presence of myenterosclerosis or tympanosclerosis [7-10].

Nowadays, two classic methods are applied in tympanoplasty that includes underlay and overlay 2 techniques. In the underlay method, the graft is medial to the hammer and the rest of the eardrum and in the overlay technique, the graft is placed lateral to the annulus and the fibrotic layer of the tympanic membrane [2]. The underlay technique is more recommended for subsequent perforations, has less risk of lateralization, and more acceptable success rate and the technique of overlay, not only is suitable for all types of perforations, but also saves the volume of the middle ear, has a good success rate especially in large and previous drilling [2]. The definition of success after tympanoplasty is not well established, but most authors refer to it as; the integrity of the graft or the tympanic membrane, the increase in the postoperative auditory threshold or the preservation of the hearing, the complete healing, which is manifested by the graft located in the correct anatomical position, without atelectasis or presence of otorrhea and recreation of the aeration of the middle ear [3,8,11].

Tympanoplasty by using temporary fascia as a graft material with different techniques has a success rate that ranges from 75% to 90% and even much higher in small perforations (less than 25%), because of its accessibility and its characteristics of elasticity and thickness, is the ideal material to rebuild the tympanic membrane, this is because the temporal fascia has no or low metabolic activity, coupled with a low viability that facilitates the growth of the medium fibrous layer of the membrane tympanic membrane and results in the formation of very strong neotympanics [12,13]. The contribution of mastoid pneumatization remains controversial, and the role of mastoidectomy in the treatment of perforations of the tympanic membrane continues to be the subject of debate, particularly in cases of chronic suppurative otitis media in the absence of cholesteatoma [7].

Some authors think that mastoidectomy is justified in case of chronic suppurative otitis media that have been refractory to antibiotic therapy, others have argued that the closure of tympanic membrane perforations and the elimination of chronic otorrhea can be achieved effectively when performs tympanoplasty with or without mastoidectomy [14,15]. Many otolaryngologists continue to routinely perform mastoidectomy with tympanoplasty, arguing that surgical aeration of the mastoid will improve the results, providing a means that can dampen pressure changes in the middle ear according to Boyle’s law, improve drainage of the middle ear and mastoid cells and in addition, it can allow surgical debridement of infected and devitalized tissues that can lead to diseases of the persistent middle ear [5,7].

The functional advantage of a large pneumatized mastoid cavity was suggested for the first time by Holmquist and Bergstrom and Ingelstedt, et al. and, later, it was motivated by Sade, et al. and Richards, et al. They theorized that when a well-pneumatized mastoid cavity communicates well with the middle ear, it acts as a buffer system to reduce the impact of pressure changes experienced by the middle ear, this allows patients with tubal dysfunction Intermittent eustachian tolerate better the negative pressure generated by periods of malfunction of the Eustachian tube [14]. Some studies show that the volume of the mastoid cells is indirectly related to the predisposition of the middle ear to certain pathological conditions [16]. Holmquist reported that the myringoplasty success correlated directly with the volume of the mastoid air chamber, taking into account only 22% of Successful closure of the perforations of the tympanic membrane when the volume of the mastoid air chamber was <5 cm2 [15].

Some other publications show that a cavity does not function as a pressure absorber and, furthermore, that the high negative pressure is caused, not by the diffusion of gases, but by evacuation of the ear during inhalation in this sense, a large cavity does not offer no benefit at all [15]. Furthermore, it has also been shown that removal of the mastoid cavity reduces residual infection and recurrent cholesteatoma and is associated with fewer secondary operations and improve functional outcome in addition to removing the mastoid cavity it alters the exchange of CO2 through the mucosa of the middle ear cavity, and this in turn can reduce the negative pressure in the graft [17].

Some other authors recommend not routinely done mastoidectomy in patients with chronic otitis media without cholesteatoma the risks caused by mastoidectomy as is sensorineural hearing loss may be due to trauma milling, meningitis that can occur due to trauma dura mater the zone of the tympanic or mastoid tegmen, massive hemorrhage that can occur due to trauma to the sigmoid sinus and facial nerve injury [5]. It has also been suggested that mastoidectomy is not only unnecessary in the treatment of non-cholesteatomatous chronic suppurative otitis media, but also increases the risks of patients with little or no significant advantage in the clinical outcome [14].

Anecdotal evidence and empirical has resulted in the common practice of making mastoidectomy with tympanoplasty for the treatment of tympanic membrane secondary to chronic suppurative otitis media colesteatomatosa [18]. Como not evidenced in the literature, tympanoplasty alone may be sufficient to repair of uncomplicated simple tympanic membrane perforations [18]. On a systematic review that was conducted in 2013 by Steven J. Eliades of a patient with chronic non-cholesteatomatous otitis media who underwent only tympanoplasty or mastoidectomy with tympanoplasty, it was concluded that there is no additional benefit in performing mastoidectomy together with tympanoplasty in uncomplicated tympanic perforations, but patient with tympanic perforations more complicated if they can benefit from the addition of mastoidectomy to tympanoplasty [7].

Another retrospective study conducted in 2015 by Rıza Dündar included 146 patients who underwent tympanic membrane repair divided into 2 groups; one where only timoanoplasty was performed and another where mastoidectomy plus tympanoplasty was performed, concluded that mastoidectomy does not create statistically significant differences in the success of the graft and the postoperative hearing results, otherwise it prolongs the duration of the surgery, increase the costs and risks to which the patient is subjected [5].

Material and Methods

The study was carried out by reviewing the complete files of the patients with the diagnosis of non-cholesteatomatous chronic otitis media who underwent mastoidectomy plus tympanoplasty or only tympanoplasty treated in the Medical Unit of High Specialty No.2 and who met the criteria of selection, during the period of time comprised between January 2015 to May 2017 by the otolaryngology medical team. This work was subject to evaluation and authorization by the hospital committee. Data were taken such as age, sex, state of origin, history of smoking, cause of perforation of the tympanic membrane, duration of dry ear prior to surgery, trans operative otoscopy, presence of otorrhea at the time of surgery, state of mucosa at the time of surgery, presence of tympanosclerosis or miringoesclerosis in the operated ear, presence of postoperative otorrhea, presence of perforation or retraction of the graft.

Statistical analysis

The data was collected in an Excel spreadsheet. We use measures of central tendency and dispersion for the quantitative variables. We use frequency and percentages for qualitative variables. We look for significant difference between the variables of the groups, which will be determined according to the realization or not of mastoidectomy, for this we will use Ch2. We compare the variables in related groups (before and after the intervention) by Mc Nemar’s test to analyze significant difference before and after the intervention. For the comparison of the quantitative variables as time of evolution between the two groups we used Student’s T or Mann Whitney U according to the distribution of the data. The analysis was carried out with the statistical package SPSS version 21 in English.

Results

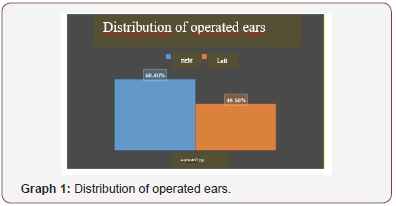

The follow-up of the patients was 3 months after the surgical procedure. A total of 48 patients were selected for the study; 31 of the female sex and 17 of the male sex, their average age was 43.25 years, with a minimum of 20 years and a maximum of 76 years. With respect to feminine gender in 33% I was performed only tympanoplasty and 31% mastoidectomy with tympanoplasty, male 11% to be performed only tympanoplasty and 25% mastoidectomy with tympanoplasty, without significant difference (p 0.13). Regarding the federative entity of origin 54% (26 patients) were from the state of Sinaloa, 40% (19 patients) from Sonora, 4% (2 patients) from Baja California Sur and 2% (1 patient) from Baja California Norte The right ear was the one that was most often operated with 60.4% compared to the left ear with 39.5% (Graph 1).

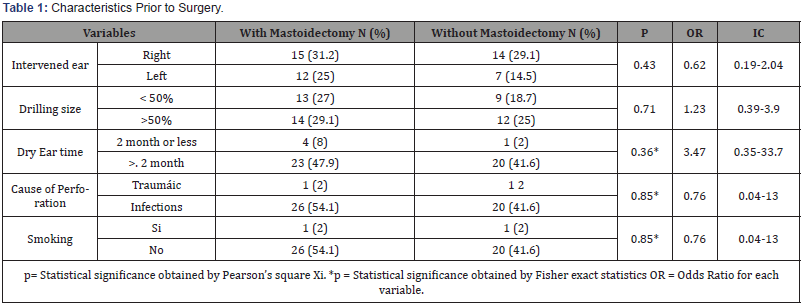

As indicated in (Table 1) regarding the characteristics prior to surgery, of the total of patients with mastoidectomy, 15 surgeries were in the right ear and 12 in the left ear and of the patients without mastoiectomy, 14 surgeries were in the right ear and 7 in the left ear, showing no significant difference (p 0.43, OR 0.6, CI 0.19-2.04). Within the group of patients with mastoidectomy, 13 (27%) patients had a perforation size less than 50% and 14 (29.1%) patients greater than 50%, and in the group of patients without mastoidecimia 9 (18.7%) had perforation. less than 50% and 12 (25%) greater than 50%, without showing a significant difference when both groups are compared (p 0.71, OR 1.23, CI 0.39-3.9). Of the patients with mastoidectomy, 4 (8%) patients had 2 months or less with dry ear prior to surgery and 23 (47.9%) patients had more than 2 months with dry ear prior to surgery, as for patients without mastoidectomy, 1 (2%) only patient had dry ear less than 2 months and 20 (41.6%) patients had dry ear more than 2 months, without significant difference between both groups (p 0.36, OR 3.47, IC 0.35 -33.7).

A close to the cause of tympanic perforation in the group of patients with mastoidectomy in 26 (54.1%) patients was of infectious origin and only 1 (2%) was of traumatic origin, in the group without mastoiectomy 20 (41.6%) were an infectious origin and only 1 (2%) of traumatic origin, without showing significant differences (p 0.85, OR 0.76, CI 0.04-13). When investigating the history of smoking only 1 patient in the mastoidectomy group with tympanoplasty had it and 1 patient in the group without mastoiectomy referred it, without showing significant difference (p 0.85, OR 0.76, CI 0.04-13).

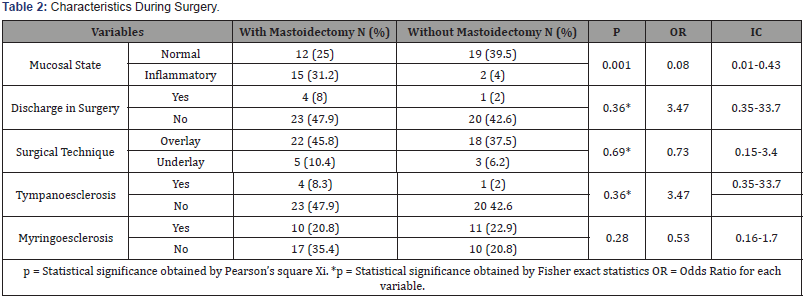

We compared both groups the variables of findings during surgery; 15 (31.5%) patients in the group with mastoiectomy had inflammatory mucosa and 12 (25%) had normal mucosa and only 2 (4%) patients in the group without mastoidectomy had inflammatory mucosal status and 19 (39.5) %) normal, showing significant difference (p 0.001, OR 0.08, IC 0.01-0.43). In 4 (8%) patients in the group with mastoidectomy they presented otorrhea at the time of surgery and only 1 (2%) in the group without mastoidecotmia, without showing significant difference (p 0.36, OR 3.47, CI 0.37-33.7). In patients with mastoidectomy 22 (45.8%) the technique was used overlay and in 5 (10.4%) the technique underlay, and in the group without mastoidecotmia in 18 (37.5%) the technique was used overlay and in 3 (6.2%) the underlay technique, without showing significant difference (p 0.69, OR 0.73, CI 0.15-3.4).

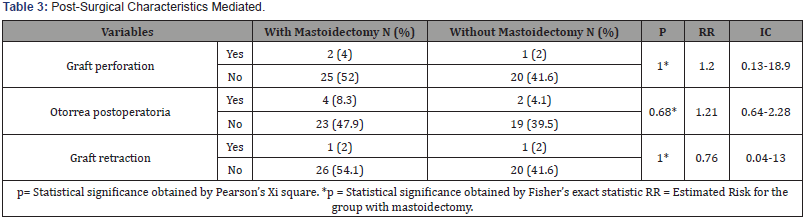

In 4 (8.3%) patients in the group with mastoidectomy they presented tympanosclerosis and only 1 (2%) in the group without mastoidectomy, without showing significant difference (p 0.36, OR 3.47, CI 0.35-33-7). In 10 (20.8%) patients had miringoesclerosis in the group with mastoidectomy and 11 (22.9%) in the group without mastoidectomy, without showing significant difference (p 0.28, OR 0.53, CI 0.16-1.7) (Table 2). Both groups were confronted on postoperative characteristics, in terms of graft perforation only 2 (4%) patients presented it in the mastoidectomy group and only 1 (2) patient in the group without mastoidecomia, without showing significant difference (p 1 , RR 1.2, CI 0.13-18.9), in 4 (8.3%) presented postoperative otorrhea in the group of patients with mastoidectomy and 2 (4.1%) patients in the patient group without mastoidectomy without showing significant difference (p 0.68, RR 1.21 , CI 0.64-2.28), only 1 (2%) presented retraction of the graft in the mastoidectomy group and 1 (2%) in the group without mastoidectomy, without showing significant difference (p 1, RR 0.76, CI 0.04-13).

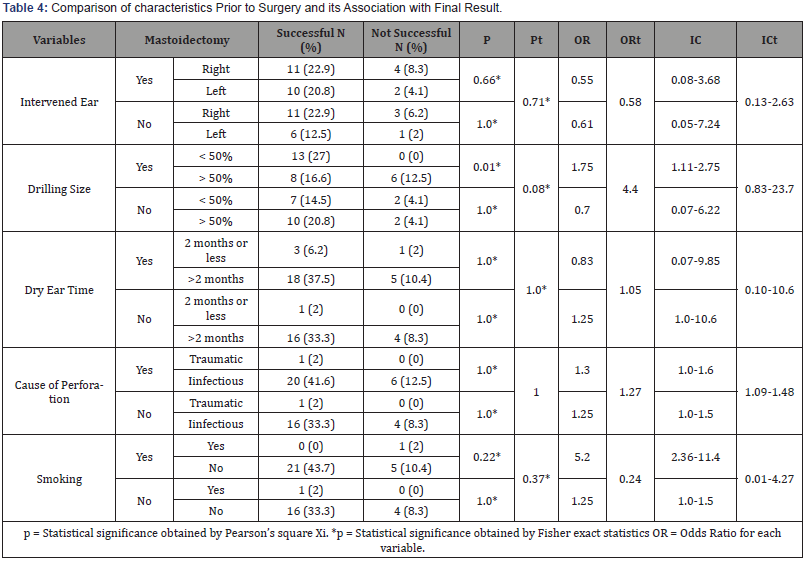

As shown in (Table 3), where we compared patients with and without mastoidectomy in terms of the characteristics prior to surgery and its association with the final result, we observed that there is no significant difference in terms of the ear operated on in patients with mastoidectomy (ear right: 11 successful and 4 unsuccessful, left ear: 10 successful and 2 unsuccessful, P 0.66, OR 0.55, IC 0.08-3.68), and without mastoidectomy (right ear: 11 successful and 3 unsuccessful, left ear: 6 successful and 1 not successful, P 1.0, OR 0.61, CI 0.05-7.24) comparing both groups there is no significant difference Pt 0.71, ORt 0.58, ICt 0.13-2.63.

The size of the tympanic perforation showed no significant difference in patients who underwent mastoidectomy (<50%, 13 successful and none unsuccessful,> 50%, 8 successful and 6 unsuccessful) with a P 0.01, OR 1.75, IC 1.11 -2.75, no, so in patients who did not undergo mastoidectomy (<50%, 7 successful and 2 unsuccessful,> 50%, 10 successful and 2 unsuccessful) with a P 1.0, OR 0.70, CI 0.07-6.22, comparing both groups there was no significant difference in the final result and the size of the perforation; Pt 0.08, ORt 4.4, ICt 0.83-23.7.

The duration of dry hearing prior to surgery (Table 4) showed no significant difference in the final result in a patient with mastoidectomy (≤ 2 months; 3 successful, 1 unsuccessful, >2 months; 18 successful and 5 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 0.83, CI 0.10- 10.6, or patients without mastoidectomy (≤ 2 months, 1 successful, 0 unsuccessful,> 2 months, 16 successful and 4 unsuccessful), comparing both groups, there was no significant difference in the final result and duration of the study. dry ear prior to surgery Pt 1.0, OR 1.05, ICt 0.10-10.6.

The cause of tympanic perforation showed no significant difference in the final result in patients with mastoidectomy (Traumatic, 1 successful, none unsuccessful, Infectious, 20 successful and 6 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 1.3, CI 1.0-1.6, or in patients without mastoidectomy (Traumatic, 1 successful, none unsuccessful, Infectious, 16 successful and 4 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 1.25, CI 1.0-1.5, comparing both groups there was no significant difference in the final result and the cause of perforation tympanic Pt 1.0, ORt 1.27, ICt 1.09-1.48. Smoking did not show significant difference in relation to the final result in patients who underwent mastoidectomy (Yes, none successful, 1 unsuccessful, No, 21 successful, 5 unsuccessful) P 0.22, OR 5.2, IC 2.36-11.4, neither in patients without mastoidectomy (Yes, 1 successful and none unsuccessful, No, 16 successful, 4 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 1.25, CI 1.0-1.5, comparing both groups there was no significant difference Pt 0.37, ORt 0.24, ICt 0.01-4.27.

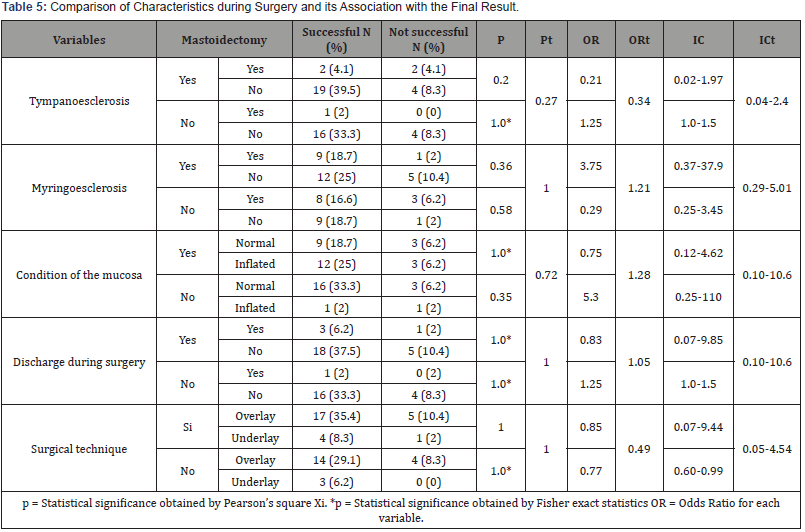

In (Table 5) we compared patients with and without mastoidectomy in terms of characteristics during surgery and its association with the final result, observing that there is no significant difference in the presence of tympanosclerosis and its final result in patients with mastoidectomy. (Yes, 2 successful and 2 unsuccessful, No, 19 successful and 4 unsuccessful) P 0.20, OR 0.21, CI 0.02- 1.97, or in patients without mastoidectomy (Yes, 1 successful, and 0 unsuccessful, no; 16 successful and 4 not successful) P 1.0, OR 1.25, CI 1.0-1.5, comparing both groups there was no significant difference between them either; Pt 0.27, ORt 0.34, ICt 0.04-2.4. The presence of myenterosclerosis showed no significant difference in the final result in patients with mastoidectomy (Yes, 9 successful and 1 unsuccessful, No, 12 successful and 5 unsuccessful) P 0.35, OR 3.75, CI 0.37-37.9, or in patients without mastoidectomy (Yes, 8 successful and 3 unsuccessful, No, 19 successful and 1 unsuccessful) P 0.58, OR 0.29, CI 0.25-3.45, comparing both groups there was no significant difference either; Pt 1.0, ORt 1.21, ICt 0.29- 5.01. The state of the mucosa showed no significant difference in the final result in patients with mastoidectomy (normal mucosa, 9 successful and 3 unsuccessful, inflammatory mucosa, 12 successful and 3 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 0.75, CI 0.12-4.62, neither in patients without mastoidectomy (normal mucosa, 16 successful and 3 unsuccessful, inflammatory mucosa, 1 successful and 1 unsuccessful) P 0.35, OR 5.3, CI 0.25.110, comparing both groups there was no significant difference either; Pt 0.72, ORt 1.28, ICC 0.30-5.36.

The otorrhea during the surgery showed no significant difference in the final result in patients with mastoidectomy (Yes, 3 successful, and 1 unsuccessful, No, 18 successful and 5 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 0.83, CI 0.07-9.85, nor in patients without mastoidectomy (Yes, 1 successful, and none unsuccessful, No, 16 successful and 4 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 1.25, CI 1.0-1.5, comparing both groups there was no significant difference either; Pt 1.0, ORt 1.05, ICt 0.10- 10.6. The surgical technique showed no significant difference in the final result in patients with mastoidectomy (Overlay, 17 successful and 5 unsuccessful, Underlay, 4 successful and 1 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 0.85, CI 0.07.9.44, or in patients without mastoidectomy (Overlay, 14 successful and 4 unsuccessful, Underlay, 3 successful and 0 unsuccessful) P 1.0, OR 0.77, CI 0.100-0.99, comparing both groups did not show significant difference either; Pt 1.0, ORt 0.49, ICt 0.05-4.54.

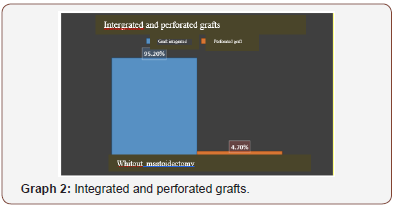

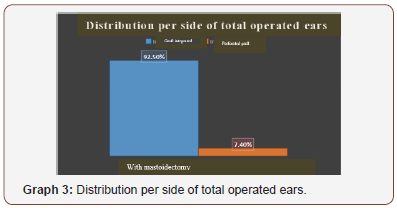

Of the 48 patients who had follow-up, 80% were considered successful (absence of postoperative otorrhea, absence of graft retraction and complete grafting), 12% presented postoperative otorrhea, 6% graft perforation and 2% graft retraction of the 48 tympanoplasty in relation to the integration of the graft, we observed that 94% had the complete graft and 6% perforated (Graph 2). When separated by group, patients who did not undergo mastoidectomy had 95% of intact grafts and 4.7% of perforated grafts (Graph 3) and patients who underwent mastoidectomy had 92.5% of grafts and a 7.4 % of perforated grafts.

Conclusion

In the surgical treatment of OMC, especially in noncholesteatomatous cases, mastoidectomy is not always a necessary intervention, being one of the most important justification that this operation would provide a better drainage of the middle ear effusion, and open mastoid air cells would increase aeration, which would facilitate the regression of the disease [5]. In our hospital, we obtain TAC of temporal bone for all patients with OMC who will undergo surgery for at least 12 months prior to surgery. We performed tympanomastoidectomy through a postauricular approach, however mastoidectomy in patients programmed especially for tympanoplasty remains controversial. Dündar R, et al found that in cases of patients without cholesteatoma programmed for tympanoplasty, the mastoidectomy does not create statistically significant differences with respect to the success of the graft and the results of the postoperative hearing [5].

In a systematic review conducted by Eliades and Limb in 2013 on the results of tympanoplasty with and without mastoidectomy in patients with perforation of the tympanic membrane without cholesteatoma concluded that the available data do not show any additional benefit for performing a mastoidectomy with tympanoplasty for uncomplicated perforations, 7 similar to that found in our study. case series. In this work, we evaluated patients with sclerotic mastoid bone detected by CT who had undergone tympanoplasty with or without mastoidectomy, we did not find any statistically significant difference between both groups regarding the success of the surgery.

Of the unsuccessful patients 4 presented postoperative otorrhea in the group of patients with mastoidectomy and 2 patients in the group without mastoidectomy, we considered that the follow-up of the study was very short-term, since most of the otorrhea were treated with medical treatment as throughout its evolution. When comparing the success of the surgery obtained only by the integration of the tympanic graft in our study, it resulted in 95.2% in patients without mastoidectomy and 92.5% in patients with mastoidectomy, with a global average of 94% in follow-up. 3 months after surgery, against 75-90% reported in the international literature [12]. In Mexico, a retrospective study conducted by Solórzano BJV that included 56 patients found a success in the integration of the tympanic graft of 85.7% [13].

When comparing both groups, the association of the characteristics prior to surgery, such as perforation size, dry ear time prior to surgery, cause of perforation and smoking history, we did not find any statistically significant difference with the result of the surgery. However, when comparing by group we found that the size of the tympanic perforation in the group of patients with mastoidectomy did influence the final result, with worse results with perforations greater than 50% with a p 0.01. Active otorrhea at the time of surgery presumably reflects active infection more recently compared to patients with dry ears, in a systematic review conducted by Steven J.

Eliades evaluated the role of mastoidectomy performed with tympanoplasty for tympanic perforation where they were reviewed 26 articles of which 8 compared otorrhea at the time of surgery vs dry ear, showing worse graft success rates for active disease in six studies and better in two 7. In that same review, 5 studies compared the results based in the size of the perforation of the tympanic membrane, there was a general tendency towards poorer results, both in the success of the repair and in the hearing with larger perforations [7].

In a retrospective study conducted by Molina Pichardo H and García Enríquez B in Mexico, where the objective was to determine the relationship between drilling tympanic graft after tympanoplasty and the smoking rate, found that smoking increases the likelihood of perforation of the tympanic graft after tympanoplasty, with increased risk when smoking 10 or more cigarettes a day 10. When comparing both groups, the association of the characteristics during the surgery as Presence of tympanosclerosis, miringoesclerosis, state of the middle ear mucosa, otorrhea during the surgery, and surgical techniques type Overlay and Underlay did not find any statistically significant difference with the result end of surgery. In a study conducted by Yurttafl V, et al in 2015 where different factors that could affect the success of the graft in the tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy were evaluated, they concluded that the infection of the middle ear and the morphology of the tympanic membrane and muco.

Conclusion

In our series of cases, the mastoidectomy shows no additional benefit in the repair of the tympanic membrane in patients with chronic non-cholesteatomatous otitis media with sclerotic mastoid bone, since it does not create statistically significant differences with respect to graft success. The addition of mastoidectomy to tympanoplasty may carry unnecessary additional risks and increase surgical time and costs. Our results show that the characteristics during and before surgery did not influence the final result when comparing both groups contrary to what the literature reports. Within the limitations of our results, they are associated with a limited number of cases, which influences obtaining results with greater bias, we also consider making a longer follow-up period can add value to the present study. With this work we propose to carry out a study with a larger number of cases and a longer follow-up to obtain more conclusive results and less bias.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Campos Navarro LA, Barrón Soto M, Fajardo Dolcic G (2014) Acute and chronic otitis media, a frequent and avoidable disease. Rev Fac Med 5: 5-14.

- Rogha M, Berjis N, Taherinia A, Eshaghian A (2014) Comparison of tympanic membrane grafting medial or lateral to malleus handle. Adv Biomed Res 3: 56.

- Felipe Vega JC, Ríos Nava JR, Meléndez Valderrama S (2010) Timpanoplastia “intercapas” y cierre de membrana timpánica. Estudio comparativo y aleatorio. Grupo piloto An Orl Mex 55: 37-42.

- Fernandes de Azevedo A, Castro Soares AB, Correa Garchet HQ, Alves de Sousa NJ (2013) Tympanomastoidectomy: Comparison between canal wall-down and canal wall-up techniques in surgery for chronic otitis media. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 17: 242-245.

- Dündar R, Kulduk E, Soy FK, Yazıcı H, Sakarya EU, et al. (2016) Necessity of mastoidectomy in patients with chronic otitis media having sclerotic mastoid bone: a retrospective clinical study. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg 25: 152-157.

- Abdel Tawab HM, Mahmoud Gharib F, Algarf TM, ElSharkawy LS (2014) Myringoplasty with and without Cortical Mastoidectomy in Treatment of Non-cholesteatomatous Chronic Otitis Media: A Comparative Study. Clin Med Insights Ear Nose Throat 12: 19-23.

- Eliades SJ, Limb CJ (2013) The Role of Mastoidectomy in Outcomes Following Tympanic Membrane Repair: A Review. Laryngoscope 123: 1787-1802.

- Boronat Echeverría NE, Reyes García E, Sevilla Delgado Y, Aguirre Mariscal H, Mejía-Aranguré JM (2012) Prognostic factors of successful tympanoplasty in pediatric patients: a cohort study BMC Pediatr 67: 1-6.

- Yurttafl V, Ural A, Kutluhan A, Bozdemir K (2015) Factors that may affect graft success in tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy. ENT Updates 5: 9-12.

- Molina PH, García EB (2009) Effects of smoking on the surgical results of tympanoplasty. An Orl Mex 54: 45-50.

- Rekabi H, Najarzadeh M, Lotfi S, Saki N (2016) The comparison of Tympanoplasty with or without Mastoidectomy in patients with dry Chronic Otitis Media: A randomized superiority clinical trial. Int J Pharm Res Allied Sci 5: 165-170.

- Bidkar VG, Jalisatigi RR, Naik AS, Shanbag RD, Siddappa R, et al. (2014) Perioperative Only Versus Extended Antimicrobial Usage in Tympanomastoid Surgery: A Randomized Trial. Laryngoscope 124: 1459-1463.

- Solórzano BJV, Reynoso OJ (2009) Tympanoplasty: five years of experience in a teaching hospital. An Orl Mex 54: 125-128.

- McGrew BM, Jackson CG, Glasscock ME (2004) Impact of Mastoidectomy on Simple Tympanic Membrane Perforation Repair. Laryngoscope 114: 506-511.

- Toros SZ, Habesoglu TE, Habesoglu M, Bolukbasi S, Naiboglu B, et al. (2010) Do patients with sclerotic mastoids require aeration to improve success of tympanoplasty? Acta Otolaryngol 130: 909-912.

- Swarts JD, Cullen Doyle BM, Alper CM, Doyle WJ (2010) Surface Area- Volume Relationships for the Mastoid Air Cell System and Tympanum in Adult Humans: Implications for Mastoid Function. Acta Otolaryngol 130: 1230-1236.

- Redleaf MI (2014) Air Space Reduction Tympanomastoidectomy Repairs Difficult Perforations More Reliably Than Tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope 124: 1-13.

- Hall JE, McRackan TR, Labadie RF (2011) Does concomitant mastoidectomy improve outcomes for patients undergoing repair of tympanic membrane perforations? Laringoscope 121: 1598-1600.

-

González Q, Lugo M J, Martínez V F, Portillo F J, Rubio E A. Impact of Mastoidectomy in the Repair of Tympanic Perforation in Patients with Chronic Non-Cholesteatomatous Otitis Media with Sclerotic Mastoid Bone. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 1(4): 2019. OJOR.MS.ID.000518.

-

Tympanoplasty, Sigmoid sinus, Otoscopy, Mucous membrane, Malnutrition, Cholesteatomatous, Otorrhea, Mastoidectomy, Tympanic membrane, Mastoid pneumatization.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.