Research Article

Research Article

Imaging in Simple Nasal Trauma. Is Current Practice Uniform Worldwide? –A Survey of Global Practices

Rachna Chawla, Northwick Park Hospital, UK.

Received Date: February 11, 2019; Published Date: February 19, 2019

Abstract

Background: Currently in the UK, it is accepted that imaging is no longer routinely undertaken if nasal injuries are suspected clinically. The argument for this is that it does not affect management in a clinically obvious fracture. Occasionally, nasal and septal fractures may be an incidental finding following CT head or facial bones and this can opportunistically help plan treatment. Whilst this rationale for a relatively straight forward clinical problem is generally agreed within the UK, anecdotally it appeared that this is not always the case overseas. We therefore set out to see if there was indeed a significant diversity of opinion in the assessment of what is essentially a ‘simple’ injury.

Methodology: A questionnaire was sent to surgeons across the globe. Questions included the role of imaging in the assessment of acute nasal fractures, experience of ORIF and imaging of secondary nasal deformity in their day-to-day clinical practice.

Results: 343 responses were received from 95 countries from a range of specialties: A&E, plastic surgery, ENT, OMFS and general surgery. Interestingly, in many countries plain films are still undertaken in the assessment of simple acute nasal trauma. CT imaging is occasionally performed for secondary corrective procedures.

Conclusion: Internationally, the practice and need for imaging in the assessment of nasal injuries vary greatly. Even in 2018, there still does not appear to be universally agreed diagnostic pathways for what most clinicians would consider to be a common and simple injury. Historic practice and personal opinion seem to still trump any evidence base.

Keywords: Nasal fracture; Facial trauma; International study

Introduction

Nasal fractures are one of the most common facial fractures in an adult population [1] and have been reported to be the third most common fracture of the body after the clavicle and wrist. The aetiology is varied but is mostly due to falls, fights and motor vehicle collisions [2]. The peak incidence is between the ages of 15 to 25 years [3]. In the United Kingdom (UK), the incidence continues to increase, particularly in women and may be partly attributed to an increase in ‘ladette’ culture [4].

The role of imaging in the assessment of isolated nasal trauma has evolved over the years. In the UK, many specialists today consider that isolated nasal fractures can usually be diagnosed on clinical examination alone, a rationale which is supported by the literature [5-8]. It has also been reported that even in the presence of clinically displaced nasal fractures, abnormalities may not be detected on plain films due to lack of sensitivity. In the UK therefore, imaging is generally no longer undertaken routinely for suspected isolated nasal fractures. Instead, it is argued that clinical examination is sensitive enough to diagnose fractures which require surgery (manipulation under anaesthesia) making the need for imaging obsolete. It is also widely accepted that X-rays (XR) for ‘medicolegal purposes’ should no longer be taken [9].

Whilst these arguments appear to form the basis of a generally agreed pathway within the UK, anecdotally it has been our experience that this philosophy is not always applied by our overseas colleagues. One would have thought that by now, in 2018, assessment of a relatively ‘simple’ problem would not be so controversial. The aim of this pilot survey was therefore to explore this variance in opinion further and ascertain the current philosophy and practice in the use of imaging (or not) from a global perspective. How well is the evidence base being followed elsewhere?

Methodology

Over a period of 5 months a SurveyMonkey® questionnaire consisting of 10 questions was sent to clinicians worldwide who are actively and regularly involved in the management of nasal fractures. Recruitment was achieved using the social media site LinkedIn®, where a wide variety of countries were targeted (with English speaking surgeons). Because of the differences in referral and management pathways for these injuries internationally, specialties invited to take part in this study included Accident and Emergency (A&E), plastic surgery, Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS). Over 1500 invitations to partake in the study were sent out.

At the same time a separate study was also carried out, directed only at clinicians working in the Emergency Department but those findings will not be discussed in this paper.

The questions asked in the survey were:

Q1: What is your specialty?

Q2: What country are you from?

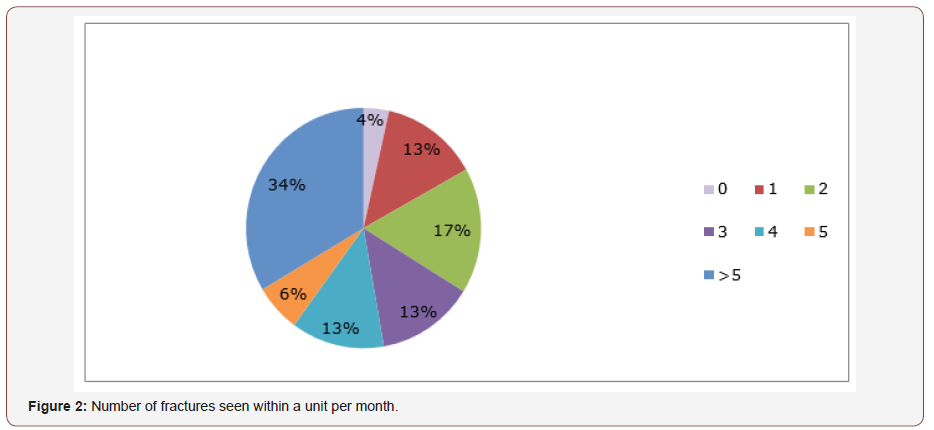

Q3: How many fractured noses do you see each month within your unit?

Q4: Have you ever seen or performed open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of a fractured nose?

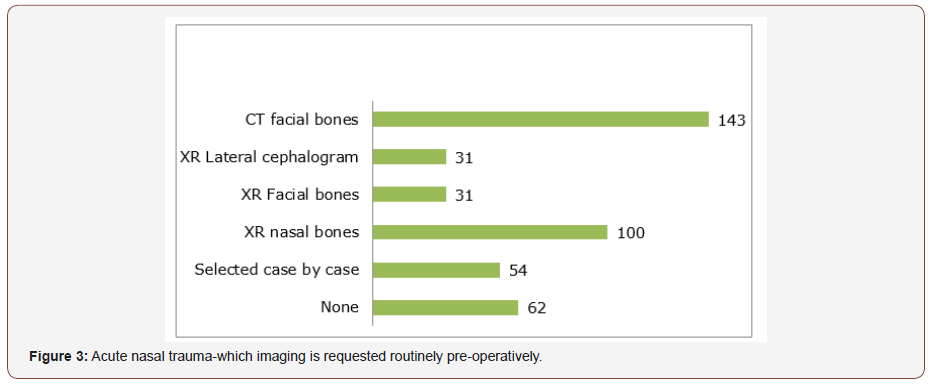

Q5: Acute nasal trauma-Do you routinely request imaging preoperatively, which views?

Q6: If no, why do you not use imaging for acute nasal injuries?

Q7: Post traumatic-Do you routinely request imaging to assess nasal deformity that requires secondary corrective surgery? If so, which views do you request?

Q8: Post traumatic-If no, why do you not use imaging?

Q9: After surgery, do you image post operatively for nasal trauma?

Q10: When would you consider a CT of the facial bones in a patient with nasal injuries?

Results

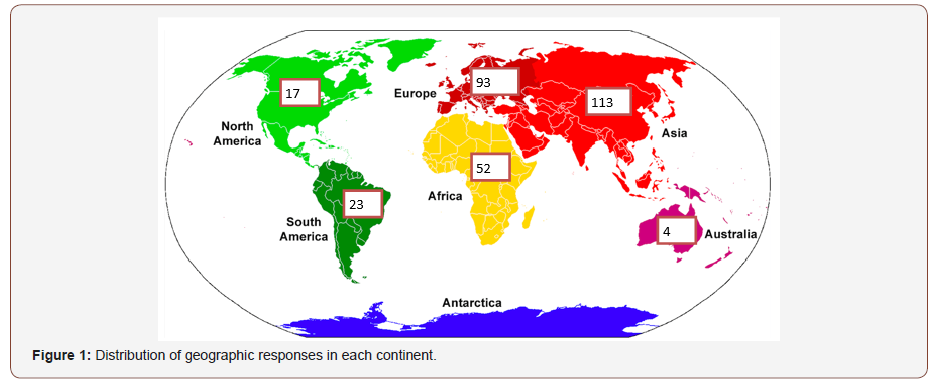

A total of 343 responses were collected from 95 countries worldwide. Of these, 123 were from the UK.

Type of Specialty: ENT (176), OMFS (103), Plastics (55), General Surgery (3), A and E (2), other (4).

177 (52%) have seen or performed Open Reduction Internal Fixation (ORIF) of nasal bones and 166 (48%) have not.

Regarding post operative imaging, it is carried out by 4 (1%) of partipants in acute nasal trauma, 24 (7%) in post trauma, 51 (15%) carried out in both acute and post nasal trauma and none is carried out in 264 (77%) of cases.

Discussion

Nasal fractures often present with an array of symptoms, commonly epistaxis, deformity or deviation, tenderness, ecchymosis and swelling. The majority of patients will initially present to their local emergency department. However, some fractures may go undiagnosed in patients who are relatively asymptomatic or unconcerned. These may be subsequently identified purely by chance later, on radiographic imaging of other facial injuries. Untreated, nasal fractures can lead to impaired function with nasal obstruction and congestion, as well as aesthetic concerns [10].

In some patients’ nasal fractures may be an incidental finding following Computer Tomography (CT) of the head or facial bones undertaken for some other reason, and this information can often be useful in counselling patients, excluding ‘deeper’ extension of the fractures (into the orbits and anterior cranial fossa) and in planning treatment. Nevertheless, routine use of CT and plain films is generally felt not to be necessary for surgical planning in apparent isolated injuries. The literature suggests that XR has a reliability only of 82% [11].

This study was conceived following a number of informal discussions between the senior author and overseas colleagues. We had long assumed that from a global perspective we were all “singing from the same song sheet” and the practice of X-raying for nasal fractures was now obsolete. However, discussions indicated this is clearly not the case out with the UK. Interestingly the results of this limited study seem to confirm that even in 2018 there is still a significantly varied approach to the assessment of nasal trauma from clinicians across the globe. Europe provided the highest number of responses of which 123 were from the UK. This may reflect a higher incidence of nasal fractures, a greater willingness to respond to the questionnaire, or a higher proportion of Englishspeaking surgeons.

Our results would suggest that nasal fractures are very commonly seen in many units across the world. The vast majority of respondents belonged to the ENT department (176 (51%)). This was followed by OMFS at 103 (30%). This confirms that nasal fractures are still predominantly managed by head and neck specialties, although some variation is noted within units and across the world.

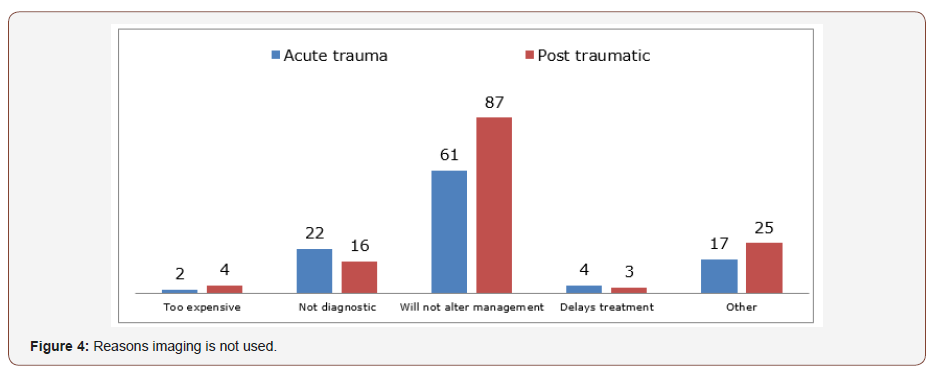

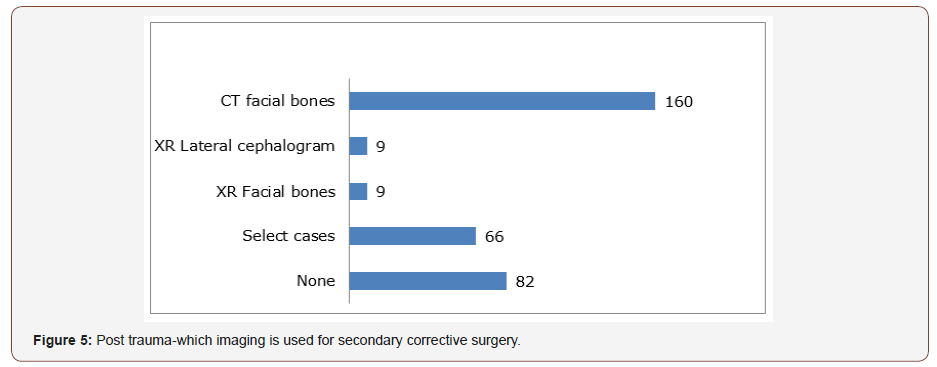

For those surgeons that did not routinely request imaging (in both acute and delayed trauma), the overriding justification was that it does not alter management. This is supported by much of the literature. When plain films were taken, these included XR facial bones/XR lateral cephalometry and XR nasal bones. XR nasal bones is still a commonly requested film. CT is usually reserved for more high energy injuries, to assess for associated injuries, the nasal septum and in severely displaced fractures. Imaging was more commonly undertaken in the acute setting. Whilst 142 (42%) of clinicians advocated the use of CT in acute nasal trauma, for post traumatic assessment this figure increased to 160 (47%) (Figure 1-3).

It has been argued that CT facial bones is only of benefit if nasal fractures are associated with other injuries [12]. The results from this study suggest that 93 (27%) of clinicians agree with this argument. High resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis of nasal fractures has also been suggested as an alternative to x-rays [13]. It is interesting to note that this has been reported to be superior to CT scan, with 100% of nasal fractures being identified, compared to 92.1% with CT. This has the obvious additional benefit of minimising radiation risks to patients (Figure 4-6).

In terms of management, there was an almost equal split in the respondents who have and have not seen/performed ORIF. This suggests that ORIF is not commonly carried out and intervention tends to mostly involve manipulation. There is currently no available evidence in the literature to support routine use of ORIF.

This was a pilot study and clearly has some limitations. One is that some countries may have limited or no access to the social media network LinkedIn and have therefore will have been excluded. Consequently, our findings may not reflect the entire global preference.

The fact that different specialties across the world operate differently is noteworthy because of the litigious nature of society and without uniformly agreed protocols it is difficult to offer a defence of practice if complications arose. There is an increase in the need to follow evidence base protocols which often forms the basis of litigation made against a clinician, making this study very relevant.

Outcomes following nasal fracture are not the same. There is a wide range of outcomes and satisfaction rates from even simple MUA. Some published studies have shown an overall deformity rate of 10.4% ± 4.8% [14] making this a significant clinical problem. Clinicians now work in an evidence-based culture, which can be used to support or attack clinical practice from a medicolegal perspective if results are poor.

The guidelines in the UK for nasal bone imaging are limited. However, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Radiology Department, Heart of England NHS Trust and the “Referral guidelines for imaging” produced in accordance with the UK Royal College of Radiologists have published that XR should not be indicated in trauma and clinical management alone is suffice [6-8].

At present, no evidence was found that imaging provides any benefit to surgical outcomes. There is, however, evidence to suggest that certain imaging modalities are more effective at the diagnosis of fracture, for instance CT over conventional imaging [15].

Conclusion

This study reveals that imaging of isolated nasal fractures both in acute and post traumatic fractures is still common practice across the world. Choice of imaging also varies. It would appear therefore that even a ‘straightforward’ clinical problem, such as the diagnosis of an isolated broken nose is still not universally agreed. More education and debate are therefore needed between countries and specialties to determine what clinical value, if any, there is to routine use of imaging to define which patients will benefit from imaging and to reduce inappropriate irradiation in patients where there is no clinical benefit. In many countries plain films of the nose are still undertaken routinely for simple fractures and CT imaging is more frequently performed for secondary corrective procedures. Whilst this paper has not explored in detail the reasons behind this variation, it would be suspected that cultural, economic, legislative and patient expectations to be major driving forces.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank all participants that kindly contributed to this study. I would like to extend my gratitude to London North West Healthcare Trust for funding membership of the SurveyMonkey® account to collect data for this study.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Yabe T, Tsuda T, Hirose S, Ozawa T (2012) Comparison of Pediatric and Adult Nasal Fractures. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 23(5): 1364-1366.

- Green KM (2001) Reduction of nasal fractures under local anaesthetic. Rhinology 39(1): 43-46.

- Fornazieri MA, Yamaguti HY, Moreira JH, Navarro PL, Heshiki RE, et al. (2008) Fracture of Nasal Bones: An Epidemiologic Analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 12(4): 498-501.

- Trinidade A, Buchanan M, Farboud A, Andreou Z, Ewart S, et al. (2013). Is there a change in the epidemiology of nasal fractures in females in the UK? The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 127(11): 1084-1087.

- Smith J, Perez C (2018) Nasal Fracture Imaging: Practice Essentials, Radiography, Computed Tomography.

- Anthony S, Ostlere S (2011) Justification of exposure including referral criteria and exposure protocols guideline.

- Reynolds J (2015) Radiographic Standard Operating Protocols.

- Radiation protection 118 (2000) Luxembourg: European Commission, Directorate-General for the Environment.

- Jaberoo M, Joseph J, Korgaonkar G, Mylvaganam K, Adams B, et al. (2013) Medico-legal and ethical aspects of nasal fractures secondary to assault: do we owe a duty of care to advise patients to have a facial x-ray? J Med Ethics 39(2):125-126.

- Bremke M, Gedeon H, Windfuhr J, Werner J, Sesterhenn A (2009) Die Fraktur des Os nasale: Unfallmechanismen, Diagnostik, Therapie und Komplikationen. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 88(11): 711-716.

- Hwang K, You S, Kim S, Lee S (2006) Analysis of Nasal Bone Fractures; A Six-year Study of 503 Patients. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 17(2): 261-264.

- Kucik CJ, Clenney T, Phelan J (2004) Management of acute nasal fractures. Am Fam Physician 70(7): 1315-1320.

- Lee M, Cha J, Hong H, Lee J, Park S, et al. (2009) Comparison of High- Resolution Ultrasonography and Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Nasal Fractures. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 28(6): 717-723.

- Hwang K, Yeom S, Hwang S (2017) Complications of Nasal Bone Fractures. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 28(3): 803-805.

- Baek H, Kim D, Ryu J, Lee Y (2013) Identification of Nasal Bone Fractures on Conventional Radiography and Facial CT: Comparison of the Diagnostic Accuracy in Different Imaging Modalities and Analysis of Interobserver Reliability. Iranian Journal of Radiology 10(3):140-147.

-

Rachna Chawla, Michael Perry. Imaging in Simple Nasal Trauma. Is Current Practice Uniform Worldwide? –A Survey of Global Practices. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 1(3): 2019. OJOR.MS.ID.000512.

-

CT Imaging, Nasal Trauma, Nasal Injuries, Septal Fractures, Facial Bones, Plastic Surgery, OMF Sand General Surgery, Nasal Fractures, Facial Trauma, International Study, Clavicle, Wrist, Ladette Culture, Diagnosis, Medicolegal Purposes, Ear, Nose, Throat, Maxillofacial Surgery, Open Reduction Internal Fixation, General Surgery, Nasal Bones, Regarding Post Operative Imaging, Partipants In Acute Nasal Trauma, Array of Symptoms, Deviation, Tenderness, Ecchymosis, Swelling

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.