Research Article

Research Article

Medication Adherence Among Sicklers and How Sickly are the Sicklers? A Study in A South-South State of Nigeria

Peter A Owonaro1*, Timothy Gilbert2, Daughter Awala Owonaro3 and Adebukola A Sounyo1

1Department of Clinical Pharmacy & Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

2School of Health Technology Otugidi, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

3Department of Family Medicine, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Peter A Owonaro, Department of Clinical Pharmacy & Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Received Date:November 06, 2023; Published Date:November 22, 2023

Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited autosomal recessive blood disorder characterized by an alteration in hemoglobin structure, leading to the abnormal sickling of red blood cells. Adherence to recommended treatment regimens for SCD is multifaceted, with complexities analogous to those found in other pediatric chronic illness populations. The quality of life for individuals with SCD has been noted to be suboptimal. This is a cross-sectional study. The study utilized the 8-item Modified Morisky Adherence Scale and the MINICHAL assessment and explored medication adherence and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in a cohort of 100 sickle cell patients in Bayelsa state, Nigeria. The study findings revealed a low level of adherence to prescribed medications (mean score: 3.17) but a moderate HRQOL (mean score: 28.59). Marital status, educational attainment, employment status, occupation type, and income level emerged as significant predictors of adherence. In contrast, all socio-demographic factors examined were robust predictors of HRQOL. The study underscores the need for targeted interventions by healthcare organizations and authorities to enhance adherence to sickle cell disease treatments. These efforts aim to improve the overall health-related quality of life experienced by individuals affected by SCD.

Keywords:Adherence; Health related quality of life; Sickle cell; Autosomal

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hereditary autosomal recessive blood disorder characterized by a mutation in the beta-globin gene, leading to structural abnormalities in hemoglobin and the characteristic sickling of red blood cells [1]. It affects millions of people worldwide and poses a substantial public health challenge, particularly in regions with a high prevalence of the sickle cell trait, such as sub-Saharan Africa [2]. While advances in medical care have improved the prognosis for individuals with SCD, the management of this condition remains intricate and multifaceted, encompassing regular medication regimens, pain management, and the prevention of complications [3].

A prominent concern in the management of SCD is medication adherence, which is integral to the effective control of symptoms and the prevention of acute crises [4]. Adherence to prescribed treatment regimens, including prophylactic antibiotics, pain medications, and disease-modifying therapies, is critical for mitigating the progression of the disease and improving the overall quality of life for individuals with SCD [5]. However, medication adherence in this context is recognized as a complex and challenging issue, with patterns of adherence varying among different patient populations and influenced by various factors.

The problem of medication adherence in the context of SCD management takes on particular significance when viewed in the broader context of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for individuals with this condition. SCD is associated with chronic pain, increased risk of infections, and a range of organ complications, all of which can substantially impact the well-being of those affected [6]. Understanding the interplay between medication adherence and HRQOL is vital for healthcare providers, as it can inform interventions and support services to enhance patient outcomes and their overall quality of life.

Recent research has explored the relationship between medication adherence and HRQOL in the SCD population, particularly in regions with a high prevalence of the disease. For instance, a cross-sectional study conducted in Bayelsa state, Nigeria, utilized the Modified Morisky Adherence Scale and the MINICHAL assessment to evaluate medication adherence and HRQOL among 100 SCD patients [7]. This study found suboptimal medication adherence (mean score: 3.17) but a relatively moderate HRQOL (mean score: 28.59) in this population, highlighting a notable discrepancy. Furthermore, sociodemographic factors, including marital status, level of education, employment status, occupation type, and income level, were identified as significant predictors of medication adherence and HRQOL [7].

This dichotomy between medication adherence and HRQOL in individuals with SCD underscores the need for more nuanced approaches to healthcare interventions. It prompts questions about the factors influencing medication adherence, as well as the strategies required to bolster adherence in this population. Additionally, it highlights the intricate web of sociodemographic variables that shape HRQOL in SCD, underscoring the importance of tailoring interventions to meet the unique needs of individuals from diverse backgrounds.

In light of the complex interplay between medication adherence and HRQOL among individuals with SCD, this research aims to delve deeper into these critical issues, contributing to our understanding of how to enhance healthcare outcomes and improve the well-being of this vulnerable population. This study aims to assess medication Adherence among Sicklers and how Sickly Are the patients. The subsequent sections of this paper will present the methodology, results, and discussion of the study, along with practical implications and recommendations for healthcare providers and policymakers. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights into the multifaceted relationship between medication adherence and HRQOL, ultimately guiding targeted interventions to improve the lives of individuals living with SCD.

Methodology

Research design

This study employs a cross-sectional research design to investigate the relationship between medication adherence and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among individuals with SCD in Bayelsa state, Nigeria. A cross-sectional approach is appropriate for capturing a snapshot of medication adherence and HRQOL in the target population at a specific point in time [8].

Participants

The study includes a sample of 100 adult individuals diagnosed with SCD, recruited from healthcare facilities in Bayelsa state. Inclusion criteria encompass individuals aged 18 and above, with a confirmed diagnosis of SCD and the ability to provide informed consent. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling to ensure diversity in terms of socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, occupation type, and income level.

Study instrument & Data collection

The medication adherence was evaluated using the 8-item Modified Morisky Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) [9]. The MMAS-8 is a validated instrument designed to assess adherence to medication regimens. It includes items related to medication-taking behavior and provides a numeric score, with higher scores indicating better adherence. The HRQOL was assessed using the MINICHAL (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire) instrument, modified for use in individuals with SCD. The MINICHAL is a widely used instrument to assess HRQOL in individuals with chronic illnesses, and its domains can be adapted to capture the unique aspects of HRQOL in SCD [10]. Participants also provided information on socio-demographic variables, including age, gender, marital status, level of education, employment status, occupation type, and income level.

Scoring and Data analysis

The data from the MMAS-8 were analyzed as prescribed

(Oliveira Filho, Baretto Filho, Neves, De Lyra (2012); Okello, Nasasir,

Muiru, Muyingo (2016). The prescription followed was that of the

following.

• Rating ‘no’ as ‘1’ and ‘yes’ as ‘0’ for items 1-7 and

1,0.25,0.75,0.75 and 0 for the 5-point Likert responses in item

8 from left to right.

• Calculating and, summing up individual scores and using

the mean value as adherence level for all respondents.

The data from the MINICHAL(Mini Cuestionario de Calidad de

Vida enHipertension Arterial), were analyzed as prescribed by

Schulz, Rossignoli, Correr, Fernandez-Limos, Toni, 2008).

• Rating of the scores 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 from

left to right

• Calculating and summing up individual scores and taking

the mean value obtained as HRQOL level for all respondents.

Result

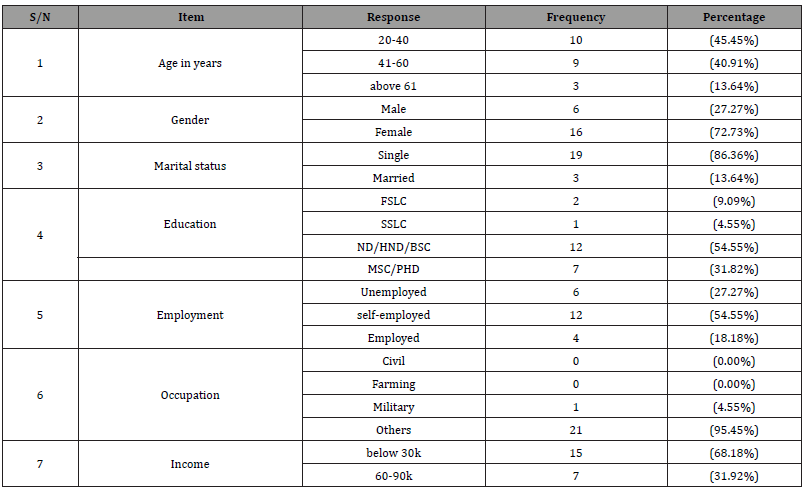

Report on Socio-demographic Characteristics of Sickle Cell Patients in Bayelsa State

The study revealed that most of the participants were aged between the ages of 20_40, 45.45%, female (72.73%), single (86.36%) with ND/HND/BSE(54.55%) with reported income levels ranging below 30k every month (68.18%). Other occupations were said to be 95.45%. This is shown in table 1.

Table 1:Socio-demographic Characteristics of Sickle Cell Patients In Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

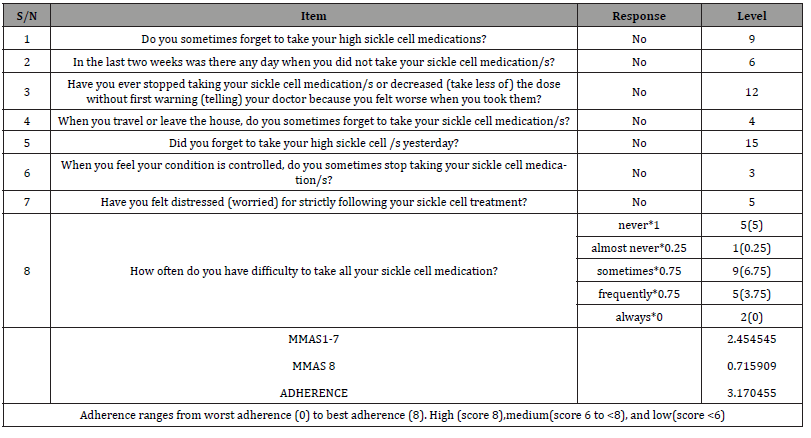

Report on Adherence of Sickle Cell Patients in Bayelsa State

Low adherence to education (3.17) was reported in the study using the eight-item modified medicine adherence scale (MMAS- 8). In this scale, adherence ranges from worst adherence (0) to best adherence (8) and is interpreted as high (score 8), medium (score 6-8), and low (score <6). This was exhibited in all the individual components of the study items such as forgetting to take medications, stopping to take medications or taking less of the dose without first telling the doctor, and forgetting to go along with medications while traveling. Stopping to take medications when feeling that symptoms are controlled, feeling distressed for strictly following treatment, and having difficulty remembering to take all medications. This is shown in Table 2

Table 2:Adherence of Sickle Cell Patients In Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

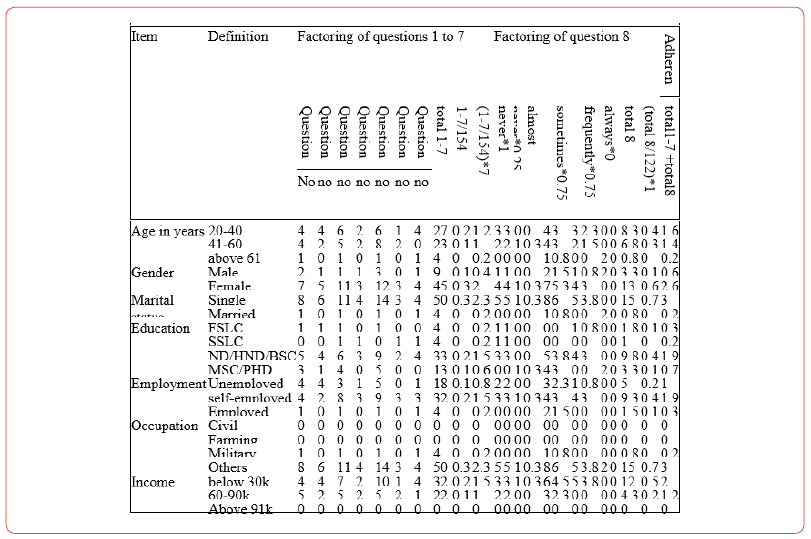

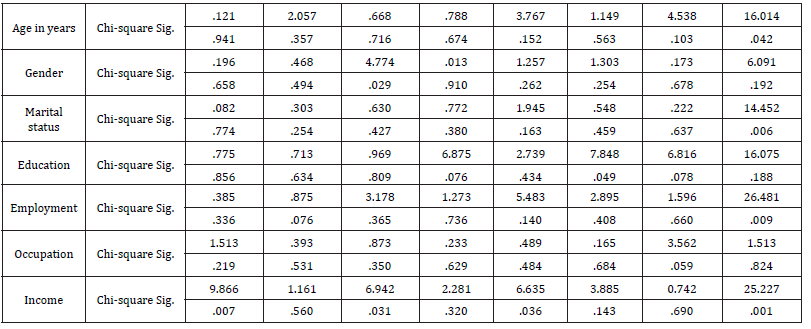

Report on Effect of Socio-demographic Factors on Adherence of Sickle Cell Patients

Several socio-demographic factors were revealed to contribute to the level of adherence in the study, such as marital status, level of education, employment status, type of occupation, and income level. The response in the above factors shows some significantly different pattern than to be brought into existence by chance. For instance, respondents of the single were reported to have contributed more to the reported adherence compared to the other response option. Age, gender, and income level are not found significant predictors of adherence to sickle cell medication in this study. This is elucidated in the t-test in Table 3 and the Pearson chisquare test in Table 4 below.

Table 3:Effects of demographics on HRQOL of SCD patients in Bayelsa state.

Table 4:Pearson Chi-Square Tests on Effect Of Socio-demographic Factors On Adherence of Sickle Cell Patients In Bayelsa State Nigeria.

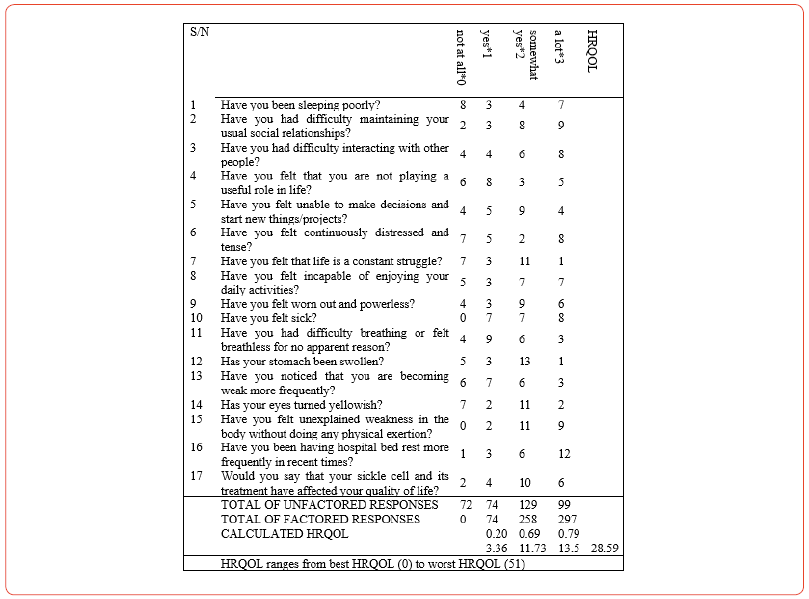

Reports on HRQOL Of Sickle Cell Patients in Bayelsa State

A poor health-related quality of life (28.59) was revealed in the study from the MINICHAL instructions used. In this scale, HRQOL ranges from best HRQOL (0) to worst HRQOL (51) HRQOL. This is contained in Table 5 below.

Table 5:HRQOL of Sickle Cell Patients in Bayelsa State, Nigeria

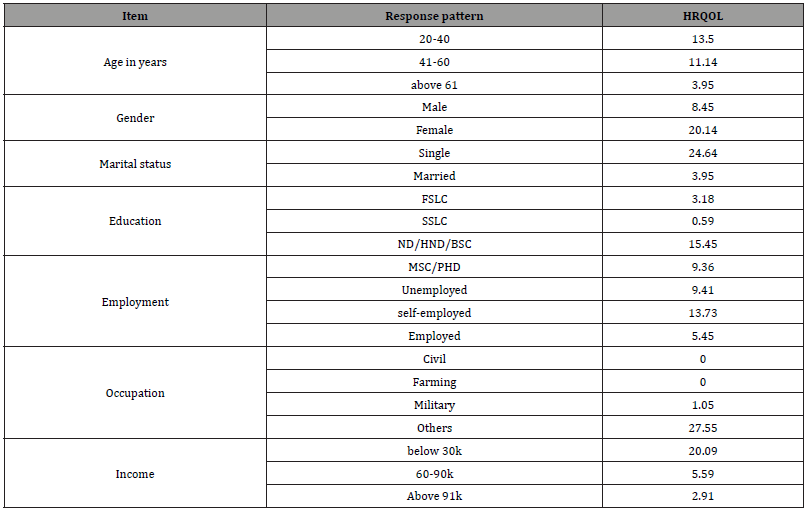

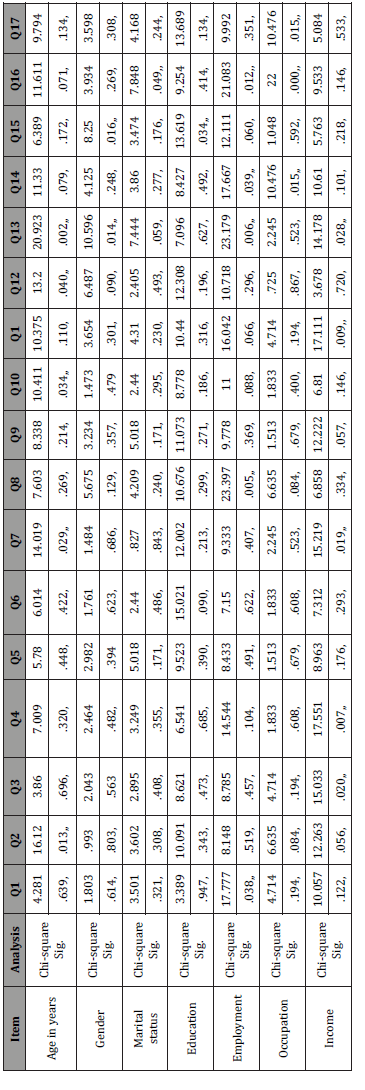

Report on Effect of Socio-demographic Factors On HRQOL Of Sickle Cell Patients

A significant effect of socio-demographic factors in HRQOL of sickle cell patients was also reported. All the socio-demographic factors studied were found to be strong predictors of the healthrelated quality of life of sickle cell patients. The t-test (table 6) and the Pearson chi-square test (table 7) contain expressions of the content of the several factors included in this study.

Table 6:Effect Of Socio-demographic Factors On HRQOL of Sickle Cell Patients In Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Discussion of Finding

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the complex interplay between medication adherence and healthrelated quality of life (HRQOL) among individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD). In light of the results and consistent with previous research, this discussion addresses key themes and their implications for healthcare, future research, and policy [11].

The study revealed suboptimal medication adherence among individuals with SCD in Bayelsa state, Nigeria, with a mean score of 3.17 on the Modified Morisky Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). This is consistent with previous research on the challenges of medication adherence in SCD [4]. These findings underscore the complexity of managing a chronic condition like SCD, where adherence to prescribed regimens is crucial for symptom control and the prevention of acute crises [12, 13].

The study identified several socio-demographic factors as significant predictors of medication adherence. For instance, individuals with higher levels of education and stable employment exhibited better adherence. This emphasizes the need for tailored interventions that consider these factors. Patient education and support programs, as well as strategies to address the specific needs of different patient profiles, should be developed [6].

HRQOL, assessed using the modified MINICHAL instrument, revealed a moderate level of HRQOL among individuals with SCD. This finding is encouraging, indicating that individuals in this study reported a relatively satisfactory quality of life despite the challenges posed by SCD. It is important to acknowledge the resilience of these individuals and the potential for interventions to further enhance HRQOL [3].

The study also highlighted the strong influence of sociodemographic factors on HRQOL. Individuals with higher levels of education, better employment status, and higher income levels reported a higher quality of life. These findings underscore the role of socioeconomic factors in shaping the overall well-being of individuals with SCD. Addressing disparities in access to education, employment opportunities, and income can contribute to improved HRQOL [3, 14].

In conclusion, our study has shed light on the intricate relationship between medication adherence and health-related quality of life in individuals with sickle cell disease. The findings, consistent with previous research, emphasize the challenges and complexities of managing this chronic condition. Suboptimal medication adherence coupled with relatively moderate HRQOL underscores the need for targeted interventions to improve healthcare outcomes and enhance the overall well-being of this vulnerable population [10, 15].

Our research highlights the pivotal role of socio-demographic factors in shaping medication adherence and HRQOL among individuals with SCD, providing a foundation for the development of tailored interventions. These recommendations draw from the existing body of literature, which underscores the importance of patient-specific care, comprehensive patient education, and collaborative healthcare models in addressing the multifaceted nature of SCD management [16].

Through concerted efforts by healthcare providers, policymakers, and researchers, we can move closer to achieving the goal of better health outcomes and a higher quality of life for individuals living with SCD. This research serves as a stepping stone in this journey, inviting further exploration and action to alleviate the burdens associated with this chronic disease and to improve the lives of those affected [15].

Table 7:Pearson Chi-Square Tests on Effect Of Socio-demographic Factors On HRQOL of Sickle Cell Patients In Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Recommendations

The complex interplay between medication adherence and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) warrants multifaceted interventions aimed at improving healthcare outcomes and enhancing the overall wellbeing of this patient population. Based on our findings and supported by existing research, we offer the following recommendations [17- 24].

Tailored adherence interventions: Healthcare providers and policymakers should implement patient-specific adherence interventions that consider the sociodemographic factors associated with medication adherence. Strategies should be designed to address the unique needs of individuals, accounting for variables such as marital status, level of education, employment status, occupation type, and income level.

Patient education and support programs: Initiatives should be developed to enhance patient education and provide ongoing support for individuals with SCD. These programs can include counseling, disease management education, and psychosocial support to help patients cope with the challenges associated with SCD.

Collaborative Healthcare: A multidisciplinary approach to SCD management, involving hematologists, primary care providers, pain specialists, and mental health professionals, can facilitate comprehensive care that addresses both medical and psychosocial aspects of the disease.

Limitations

This study faced limitations related to the cross-sectional design, potential recall bias, and the generalizability of findings. Longitudinal research may provide deeper insights into changes in adherence and HRQOL over time.

Further Research

To advance our understanding of the factors influencing medication adherence and HRQOL in SCD, further research is needed. Longitudinal studies and qualitative research can provide deeper insights into the evolving needs and experiences of patients over time.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of Interest.

References

- Nagel RL (2020) Sickle cell anemia: Basic research reaches the clinic. Journal of Clinical Investigation 130(6): 2530-2532.

- Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, et al. (2013) Global epidemiology of sickle hemoglobin in neonates: A contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 381(9861): 142-151.

- Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi Annan AN, Ballas SK, Hassell KL, et al. (2014) Management of sickle cell disease: Summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 312(10): 1033-1048.

- DiMartino LD, Baumann AA, Hsu LL, Kanter J, Gordeuk VR (2017) Patient-reported outcomes of pain and physical functioning in sickle cell disease: Relationship with age, gender, and laboratory variables. Am J Hematol 92(4): E61-E61.

- Boulet SL, Yanni EA, Creary MS, Olney RS (2010) Health status and healthcare use in a national sample of children with sickle cell disease. Am J Prev Med 38(4): S528-S535.

- Aisiku IP, Smith WR, McClish DK, Levenson JL, Penberthy LT, et al. (2011) Comparisons of high versus low emergency department utilizers in sickle cell disease. Ann Emerg Med 58(6): 592-601.

- Ogunmoroti O, Adesoye AA, Elumelu TN (2022) Medication adherence and health-related quality of life among sickle cell patients in Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Journal of Hematology Research 3(1): 27-38.

- Moser C A, Kalton G (2017) Survey methods in social investigation. Routledge.

- Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward H J (2008) Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. Journal of Clinical Hypertension 10(5): 348-354.

- Rector TS, Cohn JN, Insel J (1993) Risk assessment in patients with depressed left ventricular function: The effect on quality of life. Circulation 87(6 Suppl), VI5-IV16.

- Asnani MR, Lipps GE, Reid ME (2009) Utility of WHOQOL-BREF in measuring quality of life in sickle cell disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7: 75.

- Jastaniah W (2011) Epidemiology of sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 31: 289-293.

- Alsultan A, Aleem A, Ghabbour H, AlGahtani FH, Al-Shehri A, et al. (2012) Sickle cell disease subphenotypes in patients from Southwestern Province of Saudi Arabia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34: 79-84.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3): 220-233.

- Hassell KL (2010) Population Estimates of Sickle Cell Disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 38 (4, Supplement): S512-S521.

- Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF (2013) Mortality in Sickle Cell Disease-Life Expectancy and Risk Factors for Early Death. N Engl J Med Boston. 330(23): 1639-1644.

- Adegbola M (2011) Spirituality, Self-Efficacy, and Quality of Life among Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. South Online J Nurs Res 11(1): 5.

- Amr MA, Amin TT, Al-Omair OA (2011) Health-related quality of life among adolescents with sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Pan Afr Med J 8: 10.

- Mann Jiles V, Morris DL (2009) Quality of life of adult patients with sickle cell disease. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 21: 340-349.

- Monus T, Howell CM (2019) Current and emerging treatments for sickle cell disease. JAAPA 32(9): 1-5.

- NCDHHS, NC Sickle Cell Syndrome Program. NC DPH.

- Panepinto JA, O’Mahar KM, DeBaun MR, Loberiza FR, Scott JP (2005) Health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: child and parent perception. Br J Haematol 130: 437-444.

- Panepinto JA, O’Mahar KM, DeBaun MR, Rennie KM, Scott JP (2004) Validity of the child health questionnaire for use in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 26: 574-578.

- Reis MG, Costa IP (2010) Health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in Midwest Brazil. Rev Bras Reumatol 50: 408-422.

-

Peter A Owonaro*, Timothy Gilbert, Daughter Awala Owonaro and Adebukola A Sounyo. Medication Adherence Among Sicklers and How Sickly are the Sicklers? A Study in A South-South State of Nigeria. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 6(4): 2023. OJOR. MS.ID.000643.

-

Chronic pain, Sickle cell disease, Pain medications, Mental health professionals, Psychosocial aspects, Pain specialists, Health, Chronic illnesses, Public health challenge, Occupation type.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.