Research Article

Research Article

Parthenium (Parthenium Hysterophorus l.) Compost Characterization for Plant Nutrient Contents in Ginir District of East Bale Zone, South-Eastern Ethiopia

Tesfaye Ketema*, Mulugeta Eshetu, Girma Getachew and Regassa Gosa

Sinana Agricultural Research Center, Soil Fertility Improvement, Soil and Water Conservation and Watershed Management Team, P. O. Box 208, Bale-Robe, Ethiopia

Tesfaye Ketema, Sinana Agricultural Research Center, Soil Fertility Improvement, Soil and Water Conservation and Watershed Management Team, P. O. Box 208, Bale-Robe, Ethiopia

Received Date:November, 16, 2023; Published Date:January 19, 2024

Abstract

Parthenium (Parthenium hysterophorus L.) characterization in the southeast of Ethiopia, in the Oromia Region, the compost for Major Plant Nutrient Contents experiment was carried out in the Ginir District of the Bale Zone. As a result, the purpose of this research was to evaluate the quality and nutrient content of compost made from parthenium combined with wheat byproduct and farmyard manure. Before they began to bloom, the parthenium plants were harvested and cut into smaller pieces. As a result, parthenium compost was made using three different methods, including parthenium biomass plus farmyard manure, parthenium biomass plus crop residue, and parthenium biomass plus both farmyard manure and crop residue. Important chemical characteristics like pH, EC, OC, TN, available P, CEC, and exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, K, and Na) and micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn) were examined using standard practice laboratory techniques. The compost had high plant nutrients and significantly varied among the three Parthenium compost preparation techniques, according to the results of the final laboratory analysis of the prepared and harvested Parthenium compost. As a result, Parthenium compost provides multiple benefits, including high nutrient content, weed control, and the general environmental friendliness of using organic fertilizers.

Keywords:Nutrients; Parthenium; Parthenium Compost; Nutrient Quality; Ginir

Introduction

The aggressive invasive alien weed Parthenium (Parthenium hysterophorus L., Asteraceae) is native to America [1] has since spread to Asia, Africa, and Australia. In the 1970s, parthenium weed was first introduced to Ethiopia. The first parthenium weed was discovered in Ethiopia in 1988 at Dire-Dawa in the East and also close to Wolloo-Desse in the Northeast [2, 3] Parthenium weed was thought to have originated in subtropical North America, but its seeds were imported in the 1980s during a time of famine as a contaminant of grain food aid from major food-aid distribution centers [4]. After that, it quickly spreads throughout the entire nation, along roads and railways, in grazing areas, and on arable land, having a significant negative impact on crop production, animals, and biodiversity [5]. Parthenium is now widely distributed throughout southern Ethiopia’s central rift valley and its surrounding communities in the Afar Region, East Shewa, Arsi, and Bale.

To transform the biomass from this species into a useful material that could be used as a soil conditioner and fertilizer source, parthenium composting is an alternative conditioner [6, 7]. Environmentally friendly manures are used in agriculture when farming organically. Although the production was improved by the increased use of chemical fertilizers, the soil fertility is declining as a result of insufficient organic matter The use of organic materials is advised to reclaim this. Composting is a promising method for recycling various weeds and wastes because the finished product increases soil fertility and crop production without harming the environment. It is simple to use, safe for the environment, and helps to lessen pollution issues. [8] Although composting has been a common practice for at least a century, it is only recently that it has come to the attention of organic waste management experts everywhere [9]. In addition to competing with pasture and crop species, parthenium weed has also been identified as the cause of health issues for both humans and livestock [10]. Crop growth and development can be inhibited by parthenium if not completely controlled. In the Ginir area, parthenium weeds are heavily overgrown and impede crop growth. Farmers in the Bale zone refer to it as “Anamalee” (meaning “Only me” in Afaan Oromo) because of its aggressive coverage (Personal Communications). Parthenium, according to various authors, is the spread of this species that has a significant impact on biodiversity, agricultural production, natural ecosystem production, and overall human health [11, 12, 13]. According to several studies, Parthenium compost contains twice as much N, P, and K than Farmyard does when using the nutrient for both weed control and organic fertilizer nutrient [14].

Farmers in the study area do not compost Parthenium weed, despite the area having sufficient supplies of many important macronutrients and micronutrients for plants as well as large amounts of the weed in the area. Additionally, very few or no scientific studies have been done on the uses of parthenium as a compostable material and attempts to find a more effective method of eradicating it by using it to improve crop production. Consequently, this study was carried out with the following objectives: (1), to characterize the quality of compost produced from parthenium, and (2), to characterize the nutrient contents of compost prepared from parthenium combination with wheat residue and animal manure in terms of major plant nutrient.

Material and Methods

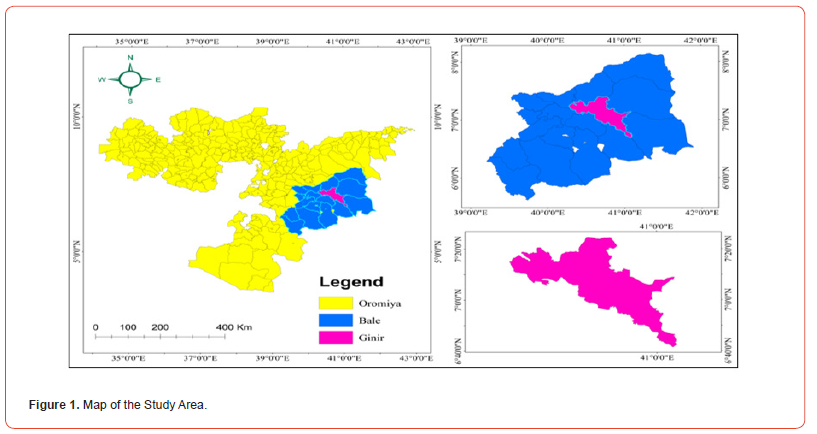

The study was conducted in the Ginir district, one of the Bale highlands in the Oromia Regional State, southeastern Ethiopia. Ginir is 519 km from Addis Ababa; Ginir is located at 07° 15′ North latitude and 40° 66′ East longitude between 1750 and 1986 meters above sea level (Figure 1). Seasonal rainfall is 531 mm and the average annual minimum and maximum temperatures are 13.4 and 25.5 °C, respectively [15]. The soil type is Vertisol. Ginir has a mono-cropping season (main season) that lasts from September to January. Ginir District is very favorable for cereal production, but also legumes, oilseeds, and horticultural crops produced by farmers.

The district’s total population was predicted by the Central Statistical Agency to be 203,751 by the year 2021 (103,592 men and 100,159 women), as stated in [16]. The district’s topography is located between an altitude of 1200 and 2406 meters above sea level. The land configuration of the district is classified as plain, which accounts for roughly 85% of its area, mountain, which accounts for 3%, and rugged and gorge areas, which account for roughly 12% (i.e., roughly 15% of this district’s, area is covered with a valley, gorges, and hills). Similar to this, the district’s land use indicates that 35.6% of the area is forested, 30.5% is arable or cultivable, 31.2% is pasture, and 2.7% is swampy mountainous, or otherwise unusable [17].

Material Used for Compost Preparation

Different substrates, including locally accessible crop residues

like corn, sorghum, haricot beans, wheat straw, teff straw, grasses,

and the entire mixture of straws and grass as a bedding material,

were used to create the compost. Equal amounts of animal Manure

were added to each substrate. To prepare the compost, the biomass

from the collected Parthenium weed was chopped and added to the

pit.

T1 = Parthenium biomass plus animal manure.

T2 = Parthenium biomass plus crop residue

T3 = Parthenium biomass plus animal manure plus crop residue.

Parthenium weed biomass, various farm crop residues, and animal Manure that were collected from the experimental site were the materials used in the experiment. Early in the rainy season, before the plants began to flower, parthenium weeds were collected and cut into pieces that could not be larger than 2.5 cm. Wheat straws were used as a reliable source of carbon to keep the process’s required C/N ratio constant. In the same way, other organic wastes like ash were used to make use of the waste and create more balanced compost.

Compost was created using a total amount and combination ratio of materials that included a parthenium-to-wheat straw ratio of 1:2.78 and a parthenium-to-cow dung ratio of 1:27.78 [14]. Freshly harvested green Parthenium weed biomass was used to make the compost. To speed up the composting process, all of the biomass was chopped into small pieces.

Preparation of Parthenium Compost

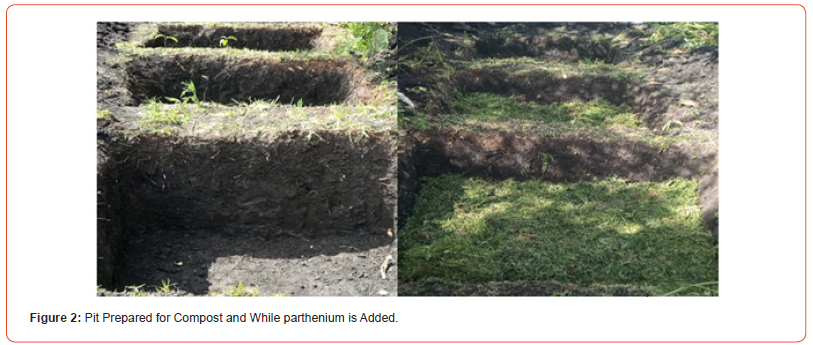

At the Farmers’ home garden, a 1 m x 1 m x 1 m Pit of parthenium compost was established. The composting unit is made of durable materials for ongoing operation. Before flowering, the Parthenium biomass was collected and cut into 1-2 inch-sized pieces. mechanically and for about 60 days with agricultural and animal wastes (Figure 2).

To keep the Parthenium Compost moist during the stacking process, water was sprayed on it. They were maintained in a semi-aerobic environment and plastered with a mixture of wheat straw, dung, and soil at the top. A turning was performed after one month, and the moisture content remained constant. On ideal temperatures and decomposition rates, good quality compost was obtained in 45 to 60 days. Water was sprinkled frequently to maintain the humidity and temperature. The materials were mixed after 20 days. The pit composting method was used to prepare the compost, and the composting process took place over the course of 60 days.

Parthenium Compost Laboratory Analysis

Samples of Parthenium Compost were taken from every compost pit. The samples were sieved before being examined for organic matter content in the Compost carried out at the Baatuu and Sinana Agricultural Research Center soil laboratories. Using a pH and conductivity meter, respectively, the pH and EC of the compost were measured in a supernatant suspension of a 1: 2.5 soil-to-water ratio [18]. [19] technique for calculating organic carbon. The Kjeldahl method, as described by [20] was used to determine the total nitrogen. Total exchangeable bases (Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Na+) were measured using flame photometers for K+ and Na+ and atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) for Ca2+ and Mg2+[21]. Using the method proposed by Chapman [21], cation exchange capacity (CEC) was calculated

Results and Discussion

Selected Chemical Properties of Parthenium Compost The pH and Electrical Conductivity of Parthenium Compost

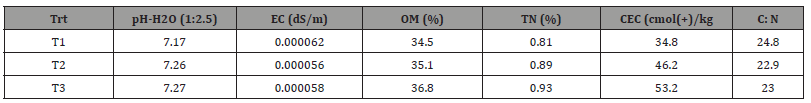

The results showed that the Parthenium biomass combined with animal manure, Parthenium biomass plus animal manure, and Parthenium biomass plus wheat straw had the highest (7.27) and lowest (7.17) pH values, respectively (Table 1). This result is consistent with [22], where the pH range for the compost was between 6.8 to 8.41. According to the research done by Araya [22] and Tadele [23], the high Electrical Conductivity (EC) was caused by a high K level, which is associated with higher pH. The application of Parthenium compost does not affect the pH of the soil, according to the value cited in Hazelton and Murphy, [24],. where it states that the pH values obtained from the Parthenium compost ranges are neutral. There was no significant variation in Electrical conductivity (Ec) values between all treatment arrangements (Table 1). According to Santamaria [25] and Hazelton and Murphy; [24], the EC values of Parthenium compost were free from salinity content. The increase of EC might be due to the slight increase in Potassium ions (K+) and other ions as decomposition proceeds. The increase in EC is due to the release of mineral salts such as phosphates and ammonium ions through the decomposition of organic substances. [26, 24].

Organic Matter, C: N Ratio and Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) of Parthenium Compost

The results revealed that the compost made from Parthenium compost plus animal manure had the lowest mean value of organic matter (34,5%) and the compost made from Parthenium compost combined with manure and crop residue the highest mean value of organic matter (36,8%) (Table 1). When compared to its availability in garden soil, Charman and Roper,[21] claim that the organic matter content in all types of Parthenium compost is extremely high. This result is consistent with the research from [23,26]. Parthenium compost treatments had very high CEC levels, ranging from 34.8 to 53.2 cm kg-1. This outcome is consistent with the research done by [26] which discovered that conventional compost contained 33.23 to 65.43 mol kg-1 of CEC. The amount of EC, OC, NT, and CEC in the compost made from Parthenium, farm yard manure, and crop residue is higher. According to the(veena.2012) report, Parthenium is a protein-rich weed that is beneficial for soil and animal feed. The CEC value recorded from Parthenium compost, according to (Metson) cited in [27] [24] ranged from high to very high, indicating that the application of Parthenium compost increases the soil’s capacity to hold and exchange cations.

Table 1:Chemical characteristics of the compost.

T1 = Parthenium compost + manure; T2 = Parthenium compost + crop residue, T3 = Parthenium compost + manure + crop residue

Total Nitrogen of Parthenium Compost

According to the results of the current investigation, the Parthenium weed’s composition in terms of the major nutrients was estimated to be [24] lowest from Parthenium compost plus farm yard manure at 0.81 and (0.93%). Compost made from Parthenium plants along with farm yard manure and crop residue had the highest nitrogen content. The outcome is consistent with the work of [38, 22 and 14]. According to [3] Values from Parthenium compost range from low to very high total nitrogen.

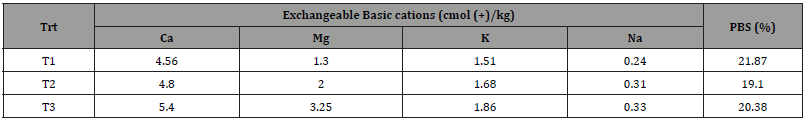

Exchangeable Bases (Ca, Mg, K, and Na) of Parthenium Compost

According to analysis, Ca, Mg, K, and Na exchangeable base values ranged from 4.56 to 5.40 mol (+)/kg, 1.30 to 3.25 mol (+)/ kg, 1.51 to 1.86 mol (+)/kg, and 0.24 to 0.33 mol (+)/kg, respectively (Table 2). The combination of wheat straw and manure with parthenium biomass produced the relatively highest values of exchangeable bases. The least valuable compost was made from parthenium biomass combined with animal manure and wheat straw. This outcome is consistent with the [28] conclusion. In general, compost made from Parthenium and manure combined was richer in exchangeable cations than compost made solely from manure. These results lend support to Amir and Fouzia’s [29] assertion that compost made from parthenium had significantly higher levels of exchangeable bases (Ca, Ma, and K). Compost made with mixed farmyard manure and biomass is obtained from Parthenium compost. The individual cations have been expressed as a percentage of the Effective CEC, according to [27] [24] registrations from Parthenium compost that show very high Ca, high to very high Mg, very low K, and low to low very Na according to [27-35].

Table 2:Exchangeable Basic cations.

Where T1 = Parthenium compost + manure; T2 = Parthenium compost + crop residue, T3 = Parthenium compost + manure + crop residue

Conclusions and Recommendation

Parthenium (Parthenium hysterophorus), which is widely distributed throughout almost all agro-ecologies, has grown to be a serious threat to agricultural productivity and land productivity. There have been numerous attempts by the government and various organizations to stop or slow down this expansion, but so far no appreciable change has been seen. A novel way to get the most out of parthenium weed and, as a result, control its spread is to compost it. Comparing compost to farmyard manure, compost has better macro- and micronutrient content. They significantly boost crop yield while also improving soil fertility. Composting parthenium there will allow it to be used effectively as organic manure and stop its alarming spread. The current studies have identified the use of environmentally friendly technologies for sustainable soil productivity, crop production, and weed control. In comparison to compost made from parthenium biomass alone, parthenium compost made from parthenium biomass along with both farm yard manure and crop residue had better nutrient contents. According to the study, it is generally advised to raise awareness among the general public— especially among farmers—about the impact of Parthenium hysterophorus on ecosystems, agricultural productivity, and management strategies. In general, more research is required to determine the rate of application of Parthenium compost and its impact on crop yields and the physical and chemical characteristics of soil in field experiments.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge the Oromia Agricultural Research Institute for its financial support. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to the staff of Sinana Agricultural Research Center’s soil fertility improvement and soil and water conservation research teams for their active participation in the execution of this experiment. We appreciate the cooperation of the Batu Soil Research Center in our experiments with sampling analysis.

Conflict of Interest

Author declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Kohli RK, Batish DR, Singh HP, Dogra K (2006) Status, invasiveness, and environmental threats of three tropical American invasive Weeds (Parthenium hysterophorus L., Ageratum conyzoides L, Lantana camara L.). Biological Invasions 8: 1501-1510.

- Seifu W/Kidan (1990) Parthenium hysterophorus L A Recently Introduced Noxious Weed to Ethiopia. A Preliminary Reconnaissance Survey Report on Eastern Ethiopia. East Hararge Ministry of Agriculture, Ethiopia.

- Bruce RC, Rayment GE (1982) Analytical methods and interpretations used by the Agricultural Chemistry Branch for Soil and Land Use Surveys. Queensland Department of Primary Industries. Bulletin QB8 (2004), Indooroopilly, Queensland.

- Tamado T, Milberg P (2000) Weed flora in arable fields of eastern Ethiopia with emphasis on the occurrence of Parthenium hysterophorus. Weed Res 40: 507-521.

- Tefera T (2002) Allelopathic effects of Parthenium hysterophorus extracts on seed germination and seedling growth of Eragrostis tef. J Agron Crop Sci 188: 306-310.

- Anbalagan M, Manivannan S (2012) Assessment of the impact of invasive weed Parthenium hysterophorus L. mixed with organic supplements on growth and reproduction preference of Lampito mauritii (Kinberg) through Verm technology. Int. J. Environ. Biol. 2 (2): 88-91.

- Jelin J, Dhanarajan MS (2013) Comparative physicochemical analysis of degrading Parthenium (Parthenium Hysterophorus) and sawdust by a new approach to accelerating the composting rate. Int. J. Chem. Environ. Biol Sci 1 (3): 535-537.

- Biradar CM, Saran S, Raju, PL N, Royb PS (2005) Forest Canopy Density Stratification: How Relevant Is Biophysical Spectral Response Modelling Approach? Geocarto International 20: 1-7.

- Yadav (2015) Assessment of different organic supplements for degradation of Parthenium hysterophorus by vermitechnology Journal of Environmental Health Science & Engineering 13: 4.

- Devi YN, Dutta BK, Sagolshemcha R, Singh NI (2014) Allelopathic effect of Parthenium hysterophorus L. on growth and productivity of Zea mays L. and its phytochemical screening. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 3: 837-846.

- Wabuyele E, Lusweti A, Bisikwa J, Kyenune G, Clark K, et al. (2014) A roadside survey of the invasive weed Parthenium hysterophorus (Asteraceae) in East Africa. Journal of East African Natural History 103(1): 49-57.

- Ayele Shashie, Nigatu, Lisanework, Tana, Tamado, Adkins SW (2014) Impact of parthenium weed (Parthenium hysterophorus L.) on the above-ground and soil seed bank communities of rangelands in Southeast Ethiopia.

- Kumari P, Sahu PK, Soni MY, Awasthi P (2014) Impact of Parthenium hysterophorus L. invasion on species diversity of cultivated fields of Bilaspur (C. G.) India. Agricultural Sciences 5: 754-764.

- Ameta SK, Benjamin S, Ameta R, Ameta SC (2016) Vishishta Composting: A Fastest Method and Eco-Friendly Recipe for Preparing Compost from Parthenium hysterophorus Weed. J EarthEnviron Health Sci 2(3): 103-108.

- Mesfin Boja, Nigusu Girma (2022) The Perception of Local Peoples About Parthenium Hysterophorus Invasion and Its Impacts on Plant Biodiversity in Ginir District, Southeastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Natural Resource Ecology and Management 7(1): pp. 42-53.

- Boja M, Girma Z, Dalle G (2022) Impacts of Parthenium hysterophorus L. on Plant Species Diversity in Ginir District, Southeastern Ethiopia. Diversity 14: 675.

- (2022) Ginnir distinct agricultural office.

- Rhoades JD (1982) Cation Exchanges Capacity. In: Page, A. L., Buxton, R. H. and Miller Keeney, D. R., Eds., Methods of Soil Analysis, Am Soc Agron, Madison: 149-158.

- Walkey A, Black IA, Walkey A, Black IA (1934) Determination of Organic Matter in Soil. Soil Science 37: 549-556.

- Bremner JM, Mulvaney CS (1982) Nitrogen-Total. In: Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties, Page, A. L., Miller, R. H. and Keeney, D. R. Eds., American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America, Madison, Wisconsin: 595-624.

- Charman PE V, Roper MM (2007) Soil organic matter. In ‘Soils – their properties and management’. 3rd (Eds P. E. V. Charman and B. W. Murphy.) pp. 276-285.

- Hailu Araya, Mitiku Haile, Arefayne Asmelash, Sue Edwards, Tewolde Berhan Gebre Egziabher (2015) Overcoming the Challenge of Parthenium Hysterophorus through Composting Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology 1(6): 72-77.

- Tadele Geremu, Habtamu Hailu, Alemayhu Diriba (2020) Evaluation of Nutrient Content of Vermicompost Made from Different Substrates at Mechara Agricultural Research Center on Station, West Hararghe Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 5 (4): 125-130.

- Hazelton P, Murphy B (2007) Interpreting Soil Test Results: What Do All the Numbers Mean? CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood.

- Santamaria RS, Ferrera CR, Almaraz SJJ, Galvis SA, Barois BI (2001) Dynamics and relationships among microorganisms, C-organic and N-total during composting and vermicomposting. Agrociencia-Montecillo 5 (4): 377-384.

- Mulugeta Eshetu, Daniel Abegeja, Tilahun Chibsa, Negash Bedaso (2022) Worm Collection and Characterization of Vermicompost produced using different worm species and waste feeds materials at Sinana on – Station of Bale highland southeastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental and Agriculture Research 8 (2).

- Metson AJ (1961) Methods of chemical analysis for soil survey samples. Soil Bureau Bulletin No. 12, New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research pp. 168–175.

- Channappa Gowda BB, Biradar NR, Patil JB, Gasimani CA (2007) Utilization of weed biomass as an organic source in sorghum. Karnataka J Agric Sci 20: 245-248.

- Amir Khan and Fouzia Ishaq (2011) Chemical nutrient analysis of different composts (Vermicompost and Pitcompost) and their effect on the growth of a vegetative crop Pisumsativum. Asian Journal of Plant Science and Research 1(1): 116-130.

- Derib Kifle, Gemechu Shumi and Abera Degefa (2017) Characterization of Vermicompost for Major Plant Nutrient Contents and Manuring Value. Journal of Science and Sustainable Development 5(2): 97-108.

- Njorge JM (1991) Tolerance of Bidens pilosa and Parthenium hysterophorus l. To paraquat (gramaxone) in Kenya coffee. Kenya Coffee 56: 999-1001.

- Spiers TM, Fietje G (2000) Green waste compost as a component in soilless growing media. Compost Sci Util 8 (1): 19-23.

- Veena BK, Shivani M (2012) Biological utilities of Parthenium hysterophorus. J Appl Natural Sci 4 (1): 137-143.

- Evans HC (1997) Parthenium hysterophorus: A review of its weed status and the possibilities for biological control. Biocon N Info 18: 89-98.

- Okalebo JR, Gathua KW, Woomer PL (2002) Laboratory Methods for Soil and Plant Analysis: A Working Manual. TSBF, Nairobi.

-

Golam Rabbani*, Anindita Hridita, Johayer Mahtab Khan and Khandker Tarin Tahsin. Exploring Climatic Hazards and Adaptation Responses to Address Problems of Climate Migrants in Selected Urban Areas in Bangladesh. Online J Ecol Environ Sci. 1(1): 2023. OJEES. MS.ID.000520.

-

Climate migrants, Vulnerabilities, Adaptation, CBF, Bangladesh, Population movement, Climatic hazards, Urban areas, Storms, Cyclones, Floods, Natural disasters`

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.