Research Article

Research Article

The Association of Elevated Serum IgE and Xerostomia with Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Waleed Yahya Ahmed Al Kassar1, Yahya Alhadi2, Hassan Abdulwahab Al Shamahy1* and Mohsen Al Hamzy3

1Department of Basic Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, Republic of Yemen

22Department of Oral and Maxillo-Facial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Republic of Yemen

3Department of Conservative Dentistry and Oral Health, Faculty of Dentistry, Republic of Yemen

Hassan Abdulwahab Al Shamahy, Faculty of Dentistry, Sana’a University, Yemen.

Received Date: March 14, 2019; Published Date: March 29, 2019

Abstract

Background and objectives: Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS) is one of the most common oral mucosal diseases. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of RAS, the association of Immunoglobulin E with RAS and potential risk factors of RAS in patients at dental clinics of Sana’a universities in Sana’a city, Yemen.

Subjects and methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted from January to December 2017 and includes 2164 patients. The patients interviewed and examined by dentists and 72 were clinically diagnosed to have RAS. The patients with RAS responded to a questionnaire that included demographic background, Qat chewing habits, smoking habits, history and course of RAS episodes. They were also subjected to laboratory tests, including determination of serum IgE levels and xerostomia.

Results: The crude prevalence of RAS was 3.3%; female prevalence was 3.8% slightly higher than 2.4% of the male. There was a higher rate of RAS in age group 16-25 years (12.3%) and age group 26-35 years (9.3%) with OR=7 times and 4.1 times respectively (p<0.001). While lower rates of RAS were occurred in children under 15 years (0.41%) and older age (0.4%), (<0.001). The Mean±SD of IgE level for major RAS patients was 233±15.3IU/ml; while for minor was 127±17.3IU/ml. There was association between elevated IgE, Xerostomia, smoking habit, and chewing Qat and occurrence of major RAS (OR=6.4, 3.3, 26.8, and 7.1 respectively).

Conclusion: Elevated IgE levels and xerostomia may be considered as part of the RAS patient’s work‐up. Further research is needed to identify biological mechanisms that account for the observed associations.

Keywords: Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS); Elevated IgE; Xerostomia; Yemen

Introduction

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS), or Recurrent oral ulceration (ROU), is one of the most common oral mucosal diseases. It is the most common recurring idiopathic intra oral ulcerative disease in different parts of the world [1,2]. The prevalence of RAS in the general population ranges between 5 and 25%. Such significant differences have been reported depending on the origin of the examined groups and populations as well as on the studies’ design and methodology [3-6]. Aphthae are located on nonkeratinized mucosa; the ulcers have well circumscribed margins, erythematous haloes and yellow or grey floors. They appear first in childhood or adolescence and heal naturally within 7-14 days [7]. Aphthae are painful and interfere with daily oral behavior such as eating, speaking and swallowing [8]. The etiology of RAS lesions is unknown, but several local, systemic, immunologic, genetic, allergic, nutritional and microbial factors have been proposed as causative agents [9,10]. An association has also been proposed between RAS and psychological stress and anxiety [11-13]. Allergy has been suspected as a cause of RAS, and hypersensitivity to certain foo substances, oral microbes such as Streptococcus sanguis, and microbial heat-shock proteins have been suggested as possible causative factors [10]. Elevated IgE is pathogenesis of many allergic diseases and has role as a potential biomarker in atherosclerosis, pulmonary hypertension, ischemic reperfusion injury, male infertility, nociception, anxiety, Alzheimer’s disease, auto-immune diseases, obesity and diabetes [14]. Moreover, Almoznino, et al [15] found elevated serum IgE in RAS and associations with RAS characteristics. Lack of epidemiological research on the topic in our country Yemen has encouraged us to conduct a populationbased study to assess its prevalence, the association of elevated Immunoglobulin E, Xerostomia and potential risk factors of RAS in patients at dental clinics of Sana’a universities in Sana’a city, Yemen.

Subjects and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at dental clinics of Sana’a University and University of Science and Technology in Sana’a city, Yemen, during the period from January to December 2017. The study includes 2164 patients attending clinics in the time of the study. The patients interviewed and examined by dentists and 72 were clinically diagnosed to have RAS (minor or major). The patients with RAS responded to a questionnaire that included demographic background, Qat chewing habits, smoking habits, history and course of RAS episodes. They were also subjected to laboratory tests, including determination of serum IgE levels and xerostomia [16].

Inclusion criteria

All patients of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (infected more than two times) of any age and both sex. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis was diagnosed by dentists. Xerostomia was diagnosed according to references [16].

Exclusion criteria

Any patient having allergy (Hypersensitivity I) according to questionnaire.

Methods

Serum samples were collected from RAS patients and tested for the IgE level by determines quantitative total immunoglobulin E by the electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay “ECLIA” on cobas e 411 immunoassay analyzers (Roche diagnostic).

Data analysis

Analysis of the data was performed by using SPSS (Version 21) and the quantitative data with normal distribution was expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). Odds ratio and 95% CI were used to determine the association of RAS with Qat chewing habits, smoking habits, age, sex, elevated IgE and xerostomia. Chisquare (χ2) test was used for categorical variables and fisher exact used if any cell < 5 to determine the p ≤ 0.05 that was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research & Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences at Sana’a University. All data, including patient identification and clinical outcomes, were kept confidential.

Results

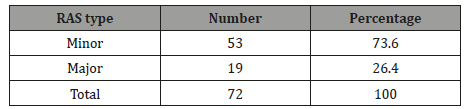

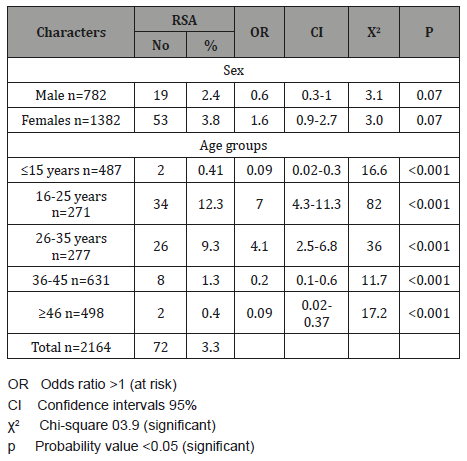

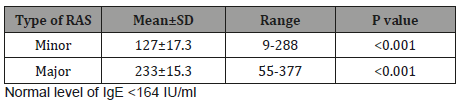

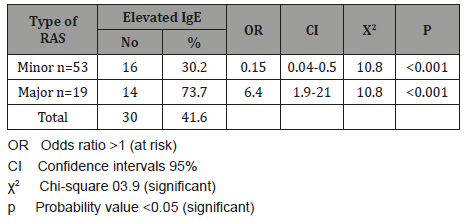

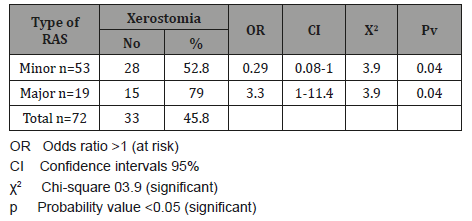

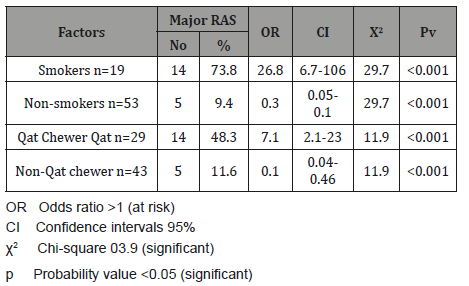

(Table 1) shows the frequency of minor and major RAS among our patients. 53 (73.6%) patients were suffering from minor RAS and 19 (26.4%) were suffering from major RAS. The crude prevalence of RAS in the current study was 3.3%; female prevalence was 3.8% slightly higher than 2.4% of male prevalence. There was no significant association of RAS with patient’s sex. When age groups were considered, a higher rate of RAS (12.3%) was occurred in age group 16-25 years with significant associated OR equal to 7 times, 95%CI =4.3-11.3 (p<0.001). The second-high rate of RAS was 9.3% for age group 26-35 years with significant associated OR equal to 4.1 times, 95%CI =2.5-6.8 (p<0.001). While lower rates of RAS were occurred in children under 15 years (0.41%) and older age groups as ≥46 years (0.4%, <0.001) (Table 2). The Mean±SD of IgE level for major RAS patients was 233±15.3IU/ml; and ranged from 55-377IU/ml, while for minor RAS the Mean±SD of IgE level was 127±17.3IU/ml; and ranged from 9-288IU/ml (p<0.001) (Table 3). The total rate of elevated IgE was 41.6%; in major RAS was 73.7% with significant associated OR equal to 6.4 times, 95%CI =1.9-21 (p<0.001) comparing with 30.2% for minor RAS without associated OR (Table 4). The total rate of Xerostomia among RAS patients was 45.8%; and it was 79% among major RAS patients (OR= 3.3 times, 95%CI =1.0-11.4, p=0.04) comparing with 52.8% for minor RAS (Table 5). There was significant association between major RAS and smoking habit (OR=26.8 times, 95%CI =6.7- 106, p<0.001). Also, there was significant association between major RAS and chewing Qat. (OR=7.1 times, 95%CI =2.1- 23, p<0.001).

Table 1: The frequency of minor and major Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis among RAS diagnosed patients in Sana’a city, Yemen.

Table 2: The prevalence of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis among different sex and age groups of patients attending dental clinics, Sana’a city Yemen.

Table 3: The IgE serum levels (IU/ml) among Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis patients in Sana’a city, Yemen.

Table 4: The association between elevated IgE and the type of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis.

Table 5: The association between Xerostomia and the type of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis.

Discussion

Recurrent Aphthous stomatitis includes periodic painful oral ulcers at breaks of a few months to a few days. RAS is common disorder and observed worldwide, seldom associated with systemic disease. In the current study 72 RAS patients have been diagnosed and classified to the 2 types of RAS in which 53 patients 73.6% were Minor RAS and 19 patients 26.4% were Major RAS. These results were roughly similar to studies carried out by Boldo, [17] and Tarakji, et al [18] where the rate of Minor RAS was 85% and Major was 15%. RAS remains the most common ulcerative disease of the oral mucosa [9]. The point crude prevalence of RAS in the current study during the study period was 3.3%; the female prevalence was 3.8% slightly higher than 2.4% of male prevalence. Our result is lower than that reported from Tur¬key [19], the prevalence was 22.8% (11,360 respondents); from Iran [20], 25.2% (10,291 respondents); and from Jordan [21], 37.3% (2,175 respondents). Also our result is lowered than that reported in the general population in different parts of the world in which RAS ranges between 5 and 25 %. [3- 6]. In this study, the female prevalence of RAS was 3.8% slightly higher than 2.4% of male prevalence with non significant variation. Our result is agreed with a study carried by Edgar, et al [22] in which they found equal rates in both males and females. However, this result disagreed with a study carried by Naikoo, et al [23] in which female RAS rate was higher than that of male rate. In the current study, when age groups were considered, a higher rate of RAS (12.3%) was occurred in age group 16-25 years with significant associated OR=7 times, 95%CI =4.3-11.3 (p<0.001) and 9.3% in age group 26-35 years (OR=4.1 times, 95%CI =2.5-6.8 (p<0.001). While lower rates of RAS were occurred in children under 15 years (0.41%) and older age groups as ≥46 years (0.4%, <0.001). Our study results were consistent with the several studies worldwide [11, 24].

One of basic aim of our study was to investigate association between elevated serum IgE levels and RAS episodes. There was statistically significant elevated serum levels IgE in RAS. The elevated levels were more common in patients with major RAS (more frequent recurrences and more severity of lesions). Scully, et al [25] in their study observed higher levels of IgE and IgD in patients of RAS than in normal controls or patients with other 14 ulcerative conditions. Also our result is agreed with studies carried by Almoznino, et al [15]; and Naikoo, et al [23] in which elevated IgE was associated with RAS. The total rate of Xerostomia among RAS patients was 45.8%; and it was 79% among major RAS patients with significant associated OR= 3.3 times, 95%CI =1.0- 11.4, p=0.04) (Table 6). This result is in agreement with others studies that reported a significant association between Xerostomia and RAS [26,27]. This result can be explained by the fact that almost all of potential factors of RAS occur combine with another symptom which is mouth dryness (Xerostomia), which might be having a role in RAS occurrence. Also the atopic background of the condition has been suggested [3,15]. In the current study, there was significant association between major RAS and smoking habit (OR=26.8 times, 95%CI =6.7- 106, p<0.001). This result is different from that reported by Ciçek, et al [19], Davatchi, et al [20], Darwazeh and Pillai [21], Axéll and Henricsson [28] and Grady, et al [29] in Turkey, Iran, Jordan, Sweden and USA in which smoking is associated with protective effect towards RAS. In the current study, there was significant association between major RAS and chewing Qat (OR=7.1 times, 95%CI =2.1- 23, p<0.001). Our study is the first study that reported Qat chewing as risk factor of major RAS.

Table 6: The association between major RAS and chewing Qat and smoking.

Conclusion

In conclusion high prevalence of RAS in Yemeni young adults, with association with smoking and Qat chewing habits. Also, elevated IgE levels and xerostomia may be considered as part of the RAS patient’s work‐up. Further research is needed to identify biological mechanisms that account for the observed associations.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Sana’a University, Sana’a, Yemen which supported this work.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest associated with this work.

References

- Schroeder Jr HW, Cavacini L (2010) Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125(2): S41-S52.

- Baccaglini L, Lalla RV, Bruce AJ, Sartori Valinotti JC, Latortue MC et al (2011) Urban legends: recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Oral Dis 17(8): 755-770.

- Rogers RS (1997) Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: clinical characteristics and associated systemic disorders. Semin Cutan Med Surg 16(4): 278- 283.

- Shashy RG, Ridley MB (2000) Aphthous ulcers: a difficult clinical entity. Am J Otolaryngol 21(6): 389-393.

- Scully C, Gorsky M, Lozada Nur F (2003) The diagnosis and management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a consensus approach. J Am Dent Assoc 134(2): 200-207.

- Liang MW, Neoh CY (2012) Oral aphthosis: management gaps and recent advances. Ann Acad Med Singapore 41(10): 463-470.

- Scully C, Porter S (2008) Oral mucosal disease: recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46(3): 198-206.

- Krisdapong S, Sheiham A, Tsakos G (2012) Impacts of recurrent aphthous stomatitis on quality of life of 12-and 15-year-old Thai children. Qual Life Res 21(1): 71-76.

- Akintoye SO, Greenberg MS (2005) Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dental Clinics 49(1): 31-47.

- Chavan M, Jain H, Diwan N, Khedkar S, Shete A, et al (2012) Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a review. J Oral Pathol Med 41(8): 577-583.

- Mc Cullough MJ, Abdel Hafeth S, Scully C (2007) Recurrent aphthous stomatitis revisited; clinical features, associations, and new association with infant feeding practices?. J Oral Pathol Med 36(10): 615-620.

- Huling L B, Baccaglini L, Choquette L, Feinn RS, Lalla R V (2012). Effect of stressful life events on the onset and duration of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med 41(2): 149-152.

- Picek P, Buljan D, Andabak Rogulj A, Stipetić Ovčarićek J, Čatić A, Pleština S et al (2012) Psychological status and recurrent aphthous ulceration. Coll Antropol 36(1): 157-159.

- Anand P, Singh B, Jaggi AS, Singh N (2012) Mast cells: an expanding pathophysiological role from allergy to other disorders. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 385(7): 657-670.

- Almoznino G, Zini A, Mizrahi Y, Aframian D (2014) Elevated serum I g E in recurrent aphthous stomatitis and associations with disease characteristics. Oral Dis 20(4): 386-394.

- Villa A, Connell CL, Abati S (2015) Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Ther Clin Risk Manag 11: 45-51.

- Boldo A (2008) Major recurrent aphthous ulceration: case report and review of the literature. Conn Med 72(5): 271-273.

- Tarakji B, Gazal G, Al Maweri SA, Azzeghaiby SN, Alaizari N (2015) Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis for dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health 7(5): 74-80.

- Ciçek Y, Canakçi V, Ozgöz M, Ertas U, Canakçi E (2004) Prevalence and handedness correlates of recurrent aphthous stomatitis in the Turkish population. J Public Health Dent 64(3): 151-156.

- Davatchi F, Tehrani Banihashemi A, Jamshidi AR, Chams Davatchi C, Gholami J, et al (2008) The prevalence of oral aphthosis in a normal population in Iran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. Arch Iran Med 11(2): 207-209.

- Darwazeh AM, Pillai K (1998) Oral lesions in a Jordanian population. Int Dent J 48(2): 84-88.

- Edgar NR, Saleh D, Miller RA (2017) Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 10(3):26-36.

- Naikoo F (2017) IgE levels in recurrent aphthous stomatitis in kashmiri popultion. Paripex - Indian Journal of Research 6(2): 413-414.

- Chattopadhyay A, Chatterjee S (2007) Risk indicators for recurrent aphthous ulcers among adults in the US. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 35(2): 152–159.

- Scully C, Yap PL, Boyle P (1983) IgE and IgD concentrations in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Arch Dermatol 119(1): 31–34.

- Du Q, Ni S, Fu Y, Liu S (2018) Analysis of Dietary Related Factors of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis among College Students. Evidence- Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 1-7.

- Mukatash Nimri GE, Al Nimri MA, Al Jadeed OG, Al Zobe ZR, Aburumman KK, et al (2017) Patients with burning mouth sensations. A clinical investigation of causative factors in a group of “compete denture wearers” Jordanian population. Saudi Dent J 29(1): 24-28.

- Axéll T, Henricsson V (1985) The occurrence of recurrent aphthous ulcers in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand 43(2): 121- 125.

- Grady D, Ernster VL, Stillman L, Greenspan J (1992) Smokeless tobacco use prevents aphthous stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 74(4): 463-465.

-

WAl Kassar WYA, Alhadi Y, Al Shamahy HA, Al Hamzy M. The Association of Elevated Serum IgE and Xerostomia with Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis. On J Dent & Oral Health. 2(1): 2019. OJDOH.MS.ID.000529.

-

Molar impaction, Teeth predispose, Periodontal disease, Pericoronitis, Periodontitis, Cystic lesions, Neoplasm, Root resorption, Detrimental effects, Yemeni population, Eruption, Impaction state, Angulation, Yemeni adult, Mandibular

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.