Research Article

Research Article

Fearing the Future: A Call to Teach Hope

Karin Richards, Department of Kinesiology, University of the Sciences, 600 South 43rd Street, Philadelphia, USA.

Received Date: December 18, 2020; Published Date:January 25, 2021

Abstract

Evaluation of the level of hope in interprofessional students, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, included: temporality and future; positive readiness and expectancy; and interconnectedness with self and others as well as an overall score of hope. With a total possible score of 48, indicating the maximum level of hope, scores ranged from 30-41. This study identified that while 85% of the participants indicated that had both short and long-term goals, 39% of the participants still felt all alone. Schools cannot neglect the vital component of hope. All higher education healthcare professionals can deviate to developing interventions and curriculum to address hope, specifically the fear of the future and lack of inner strength among our students.

Keywords:Hope, future, fear, alone

Introduction

In spring 2019, the American College of Health Association suggested 67% of college students surveyed (n= 67,972) indicated feeling very lonely and 56% of college students experiencing a lack of hope at least once during the last 12 months [1]. This finding is not unique in previous research [2-4]. Theorizes that the colder months such as after winter break may be particularly disheartening to students due to the leaving of the comforts of home and returning to the assumption of already formed social ties among peers at their respective academic institution [5]. Loneliness and hopelessness may also contribute to concerning mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety and suicide [6-9].

Hopelessness can be defined as having low motivation and disbelief in the ability of oneself to meet desired goals [10]. Having hope, therefore, can be further described as “creating positive feelings and applying inspired action” on a daily basis and especially through challenging, uncertain times [15]. Hope can be a valuable skill to teach especially among future healthcare professionals both for the clinician and the patients with whom the practitioner interacts [9,11]. Hope offers an alternative from feeling a lack of control and from the unknown which may also further improve lifestyle choices and overall well-being [11-13]. Limited research exists on the hope of Gen Z future healthcare students. Now is the time they may need it most.

Materials and Methods

A convenience sample was used consisting of all students (n=18) enrolled in the spring 2020 semester of PE 102-02. No student who chose to participate was eliminated from the study. All questionnaires were completed in their entirety.

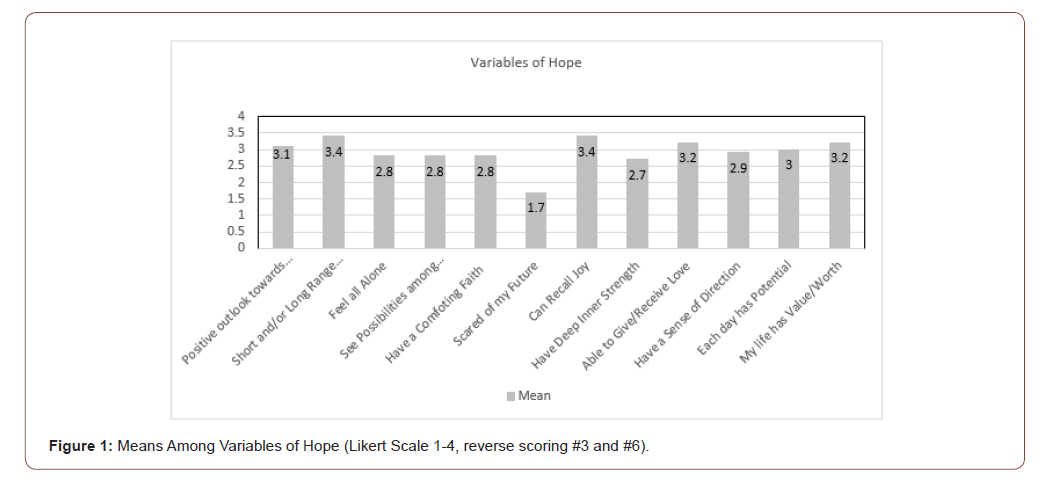

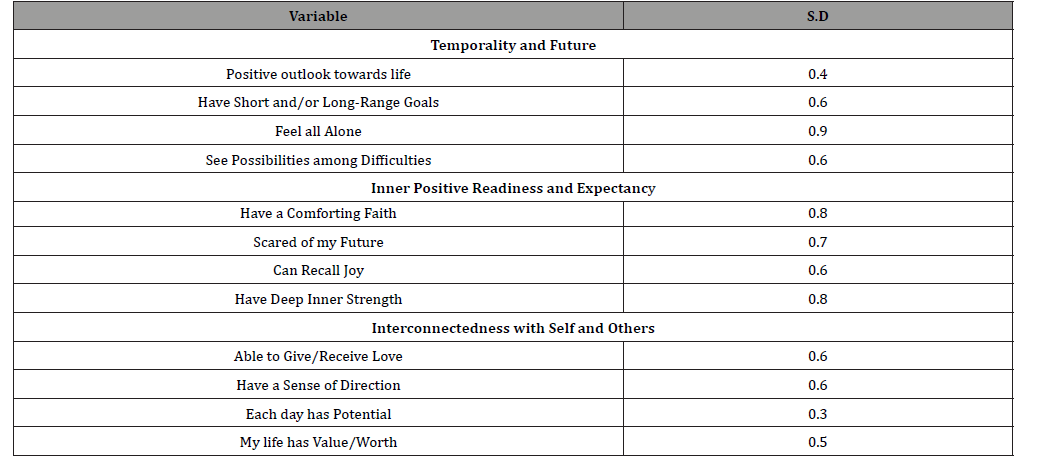

The level of hope was rated through the 12-item, previously validated, 1999 Hope Herth Index Likert scale quantitative assessment tool [14]. Each item on the Herth Index tool is rated between 1-4, (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Disagree), with possible overall scores ranging from 12-48 [14]. Items number three and six on the tool, however, are reversed scored due to the type of negative affirmation utilized in the assessment [14]. Summing all variables results in a degree of hope with higher scores suggesting elevated levels [14]. The individual variables of hope are also grouped into three categories: temporality and future; positive readiness and expectancy; and interconnectedness with self and others [14].

Descriptive statistics were used to report central tendencies and sample standard deviation of variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 26).

Results and Discussion

The majority of participants (94%) rated themselves as having a positive outlook on life, having a high sense of life’s worth and the ability to see potential in each day. Yet 89% were scared of their future and 39% of students reported feeling all alone.

Among the three categories of hope, interconnectedness with self and others was suggested to be the strongest (85%) followed by positive readiness and expectancy (79%); and temporality and future (68%). The average standard deviation among variables was .69, thus indicating little variability.

Research has consistently indicated that hope is a key component of lifelong wellness [8,9,13]. Yet university curriculums lack a focus upon teaching the concepts of hope to its students. Berg et al., (2011) suggest that engagement in healthy behaviors correlate favorably with levels of hope [13]. Ample research exists on the lifestyle choices of college students most notably which is assessed on a seasonal semester basis [1-4]. Teaching and encouraging grit, however, has been suggested to be a more acceptable measure among the academic community [15-17]. Grit has been suggested as resolution and drive towards goals, which is suggested to improve academic achievement, well-being, and personal accomplishment [15-17]. These traits, however, will not help a patient power through the latest experimental drug or cognitive speedbump when all medical effort has been exhausted. Nor will grit provide the connection needed between the healthcare provider and patient. Stitzlein (2020) theorizes that grit is more an individualistic approach to effort-focused goals whereas a hope approach is towards a communal outcome [15]. Additionally, hope has been suggested to be a bonding factor between patient and provider and facilitator of coping mechanisms [18]. Improving patient experiences starts with the healthcare provider, thus teaching how to cultivate hope first to healthcare students could be an opportunity to instill this positive trait within the future practitioner and the ability to transmit hope to the patient. The level of hope has been regularly assessed in patients, yet limited research exists on the hope in students who will one day treat these patients [18,21-23].

Table 1: Standard deviations among Herth Hope Index variables.

Academic institutions could be an ideal setting to enhancing student connection and overall wellbeing [7,8,15,24,25]. Various techniques to cultivate hope have been presented in the literature: positive affirmations, breathing techniques, mindfulness, visualization, journaling, gratitude, giving back, establishing connection among peers, promoting spiritual growth, and creating, as well as developing specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and time-bound (SMART) goals and finding encouragement through action [8,19,20,22,24,25]. Hopeful Minds, for example, is an evidenced-based curriculum designed to teach hope to elementary and middle school students [8,24,25]. Their research suggests that teaching hope is possible and results in an increase in “emotional intelligence, leadership, resiliency, self-esteem, mental health, and the prevention of suicide.” [8,24-26]. This curriculum could be adapted and implemented into higher education courses as well.

Evaluation of the role of hope offers an opportunity to assess university students’ current and future perceptions. Interventions to alleviate anxiety can instill future coping skills as well as professional interactions and realistic encouragement with patients [8,21-23]. Based on the current pilot study, students are fearful of the future. Addressing this trepidation can be integrated into the university curriculum. If academia can instruct how to power through challenges, hope can be taught to find encouraged emotion and action [8,15-17]. Teaching hope may instill the skill and belief in our students, our future healthcare practitioners, that optimism over struggle may play more of a key role in patient and personal outcomes [8,24,25].

Primary limitations of the study include the potential for random error on the part of the observer; the non-coverage bias of the segment sample; and type of sampling frame and segment participants, which limit external validity. Small sample size and sample validity are also limitations of the investigation due to the geographical locations of the university and may not be generalizable to the population. A final limitation of the study is that the study is an observational study rather than an experimental design with researcher intervention [27].

Future research should include the assessment of hope on a larger scale among future healthcare professionals, identification of specific fears of the future as well as interventions to examine the changes of perceptions of hope among students.

Conclusion

Assessing hope can provide valuable insight into students’ current and future perceptions of personal and professional life. Teaching students how to develop a stronger outlook and active skills while lessening anxiety and depression may alleviate the fear of the future and feelings of loneliness while strengthening self-efficacy. While teaching the application of hope is not a typical course in a rigorous university healthcare curriculum, maybe it should be.

Conflict-of-interest Notification

The author of this publication declares no financial, personal or other conflict of interest to this work.

References

- (2019) American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2019.

- (2018) American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2018.

- (2018) American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Reference Group Executive Summary Fall 2018.

- (2017) American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2017.

- Danzman R (2020) Why Are College Students Feeling So Lonely: and what parents can do to help. Psychology Today.

- Coverdale GE, Long AF (2015) Emotional wellbeing and mental health: an exploration into health promotion in young people and families. Perspect Public Health 135(1): 27-36.

- Mushtag R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtag S (2014) Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health: A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J Clin Diagn Res 8(9): WE01-WE04.

- Goetzke K (2020) The biggest little book about hope. Innovative Analysis, LLC.

- Sweeney S, Kirby K, Armour C, Goetzel K, Dunne M, et al. (2019) The Efficacy of ‘Hopeful Minds’: Can teaching hope improve well-being and protective factors in child and early adolescent groups. International Foundation for Research and Education on Depression White Paper.

- Snyder CR (1994) The psychology of hope: You can age there from here. New York, Simon and Schuster.

- Goodman J (2004) The anatomy of hope. The Permanente Journal 8(2): 43-47.

- Weinschenk S (2013) Why having choices makes us feel powerful. Psychology Today.

- Berg CJ, Ritschel LA, Swan DW, An LC, Ahluwalia JS (2011) The role of hope in engaging in healthy behaviors among college students. Am J Health Behav 35(4): 402-415.

- Herth K (1992) Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 17(10): 1251-1259.

- Stitzlein S (2020) Teaching Hope, Not Grit. In Learning How to Hope: Reviving Democracy through our Schools and Civil Society. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Hammond DA (2017) Grit: An important characteristic in learners. Curr Pharm Teach Learn 9(1): 1-3.

- Wolters CA, Hussain M (2015) Investigating grit and its relations with college students’ self-regulated learning and academic achievement. Metacognition Learning 10: 293-311.

- Zawitowski CA (2020) “What Hope Means to Patients.” Healio.

- Snyder CR, Anne B LaPointe, Jeffrey Crowson J, Shannon Early (1998) Preferences of High- and Low-hope People for Self-referential Input. Cognition and Emotion 12(6): 807-823.

- Huppert FA, Johnson DM (2010) A controlled trial of mindfulness training in schools: The importance of practice for an impact on well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 5(4): 264-274.

- Sanatani M, Schreier G, Stitt L (2008) Level and direction of hope in cancer patients: an exploratory longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 16(5): 493-499.

- Tavassoli N, Darvishpour A, Mansour-Ghanaei R, Atrkarroushan Z (2019) A correlational study of hope and its relationship with spiritual health on hemodialysis patients. J Educ Health Promot 8: 146.

- Baczewska B, Block B, Kropornicka B, Niedzielski A, Malm M, et al. (2019) Hope in Hospitalized Patients with Terminal Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(20): 3867.

- Kirby K, Lyons A, Mallett J, Goetzke K, Gibbons D, et al. (2019) The Hopeful Minds Programme: A Mixed-method Evaluation of 10 School Curriculum Based, Theoretically Framed, Lessons to Promote Mental Health and Coping Skills in 8–14-year-olds. Child Care in Practice 25(1).

- iFred (2020) “Hope Research.” Hopeful Minds.

- Resilio-Hopeful Minds (2020) Hope is a teachable subject.

- Aday LA, Cornelius LJ (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: A comprehensive guide (3rd edn). John Wiley & Sons, Inc, San Francisco, CA.

-

Karin Richards. Fearing the Future: A Call to Teach Hope. On J Complement & Alt Med. 5(4): 2021. OJCAM.MS.ID.000616.

-

Hope, Future, Fear, Alone, COVID-19, Hopelessness, Depression, Anxiety, Suicide, Healthcare students, Various techniques, Positive Affirmations, Breathing Techniques, Mindfulness, Visualization, Journaling, Gratitude, Giving back, Promoting Spiritual growth

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.