Research Article

Research Article

Post-deployment Social Support Predicting Successful Adjustment among Nigerian Military Returnees from Boko-Haram Insurgency

Fredrick Sonter Anongo1, James Abel2*, Binan Evans Dami3 and Aboh James Ogbole4

1 Department of Psychology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

2Department of Psychology, Shadawaka Barracks Bauchi, Nigeria

3Department of Psychology and Mental Health, International organization for Migration, Gambia

4Department of Psychology, Psychological services centre Operation LAFIYA DOLE, Maiduguri

James Abel, Department of Psychology, Shadawaka Barracks Bauchi, Bauchi State, Nigeria.

Received Date: June 13, 2019; Published Date: June 28, 2019

Abstract

GReturning from combat deployment can be a very turbulent moment for military combatants, especially when there is prolonged stay that unavoidably bring about long detachment from the society. Upon homecoming, military personnel may find it difficult to fully adjust and achieve effective societal integration, thus affecting family relationship, robust social interaction and productivity. However, existing studies have focused more on the psychological effects of war, as a result, little is known about the role that social support play in post-deployment adjustment of military personnel upon return from combat operations. This study therefore, examined the role of post-deployment social support in post-war adjustment among Nigerian military personnel exposed to Boko-Haram insurgency. Data were collected using standardized questionnaires on a sample of 322 participants. Three hypotheses were stated and analyzed using Pearson correlation and hierarchical multiple regression, and results on hypothesis one revealed a significant negative relationship between combat exposure and post-deployment social adjustment(r= -.37;p<.05), while post-deployment social support was positively associated with post-deployment social adjustment(r= .44;p<.01).Additional findings indicated a significant joint influence of combat exposure and post-deployment social support on adjustment [F(2,317 ) =29.838;R2=.27; p<.01].Result also indicated a significant interaction between Post-deployment social support and combat exposure on adjustment [ΔR2=.29, F (1, 316) =.26.16; p<.01; β= -.15, t= -2.93]. Participants who experienced combat events but had high post-deployment social support reported better adjustment( x̅ =116.47) compared to those who reported low support( x̅ =110.32). This shows that increased combat exposure could lead to poor adjustment, but providing instrumental and emotional support to the veterans after homecoming could buffer the effect of combat and increase their ability to swiftly adapt and integrate fully into the society. Therefore, Nigerian military authority, colleagues and friends of the personnel should always provide sufficient and timely support to soldiers and officers who are returning from combat operations to ensure better adjustment to the society for improved social, family and work-place performance.

Keywords: Combat exposure, post-deployment adjustment, military personnel.

Introduction

Globally, there has been a growing interest and concerns among military authorities and researchers in understanding association between military deployment and its association with subsequent psychological adjustment [1,2]. In Nigeria, for instance, research evidence suggests that a significant number of military personnel experience severe psychological problems after deployment [3,4]. However, most current knowledge of the postwar military adjustment process is has focused exclusively on psychological effects, particularly on the development of posttraumatic stress disorder [3,4].Interestingly, research evidence suggests that apart from the usual distress experience by combatants, returnee military personnel experience several changes that impede adjustment and successful societal integration [5]. Post-deployment adjustment involves successful adaptation and positive functioning in meeting challenges and responding to changes in a social environment and workplace after homecoming [6]. This includes readjustment to personal, family, work life after long period of stay in a seemingly hostile combat environment. In a normal military and societal setting where military personnel has not experienced war, he may have more time and robust interaction with his family and work, experience less anxiety and physical health concerns and be more responsive to changes in his social environment and work setting. However, after a long detachment from the society and attachment to unpleasant and unique war environment, soldiers orientation may change, and as a result, recently returned members may feel isolated or disconnected from the rest of the world thus making adjustment difficult and societal reintegration difficult [5].

Globally, there has been a growing interest and concerns among military authorities and researchers in understanding association between military deployment and its association with subsequent psychological adjustment [1,2]. In Nigeria, for instance, research evidence suggests that a significant number of military personnel experience severe psychological problems after deployment [3,4]. However, most current knowledge of the postwar military adjustment process is has focused exclusively on psychological effects, particularly on the development of posttraumatic stress disorder [3,4].Interestingly, research evidence suggests that apart from the usual distress experience by combatants, returnee military personnel experience several changes that impede adjustment and successful societal integration [5]. Post-deployment adjustment involves successful adaptation and positive functioning in meeting challenges and responding to changes in a social environment and workplace after homecoming [6]. This includes readjustment to personal, family, work life after long period of stay in a seemingly hostile combat environment. In a normal military and societal setting where military personnel has not experienced war, he may have more time and robust interaction with his family and work, experience less anxiety and physical health concerns and be more responsive to changes in his social environment and work setting. However, after a long detachment from the society and attachment to unpleasant and unique war environment, soldiers orientation may change, and as a result, recently returned members may feel isolated or disconnected from the rest of the world thus making adjustment difficult and societal reintegration difficult [5]. personnel who experience adjustment problems have been found to show greater feelings of obligation (as opposed to desire) to remain in the military, higher levels of negative job-related affect (particularly in the work domain), and greater intentions to leave the military [9].This suggests that for military personnel to perform optimally in the work-place and enjoy a robust social wellbeing after deployment, they have to adjust and be integrated fully into the society. Thus, identifying what enhance post-deployment adjustment is key for promoting reintegration and operational efficiency of military returnees from combat operations.

Interestingly, previous research have demonstrated that the support of family, friends and community members has a significant restorative role in the adaptation of military combatants [10]. [11] reported that military veterans with long-term adjustment problems are those who experience additional stress, high combat events and poor social support network. Moreover, Thompson and Gignac 2002 reported that if military members return to a unit where other members did not deploy, they may face a lack of support from their colleagues .This suggests that many returnees from the insurgency operation may be experiencing lack of social support from colleagues, especially that not every one of them was deployed. According to [4] many military personnel who have returned from the north-east have vehemently complained about lack of support and have also shown unusual aggression and cynicism, indulged in use of harmful drugs and have become a problem in their respective barracks. This suggest that, many of these personnel (with reported lack of support) may be experiencing adjustment problems, yet, little is known about the role that social support play in enhancing successful adjustment in this population. Furthermore, previous understanding on the problem of military adjustment comes from foreign studies, most of whom are conducted many years after homecoming [12]. This may make the problem unattended to for long, bringing imminent consequences on the health and inability to effectively handle prevailing situations. Short-term post-deployment adjustment is important because those who have returned needs to adapt swiftly and attend to other increasing security challenges facing the nation. Thus, short-term adaptation is crucial not just for the psychosocial wellbeing but also for its ability to guarantee rapid operational efficiency of military personnel in emerging security challenges. Incidentally, domestic studies implicate poor post-deployment social support to psychological distress among Nigerian security personnel [13]. This also suggests that inadequate social support to the returnee veterans may play a major role in their adjustment process.

During the Boko-Haram operation, military personnel were faced with devastating situations ranging from killings, witnessing death of colleagues, exposure to improvised explosives [4]. These events are extraordinary because they may overwhelm the ordinary human adaptations to life and produce profound and lasting changes in physiological arousal, emotion, cognition that may affect social life and occupational functioning. In addition, given their intense nature, traumatic experiences can alter individuals’ psychological, biological, and social equilibrium making adaptation difficult [14]. However, published researches have focused majorly on how exposure to these experiences has affected the physical and psychological health symptoms [13]. There have been little research examining the impact of psychological factors, particularly, on the role post-deployment that post-deployment social support play in military personnel’s adjustment to major areas of family work and the society. Given the deleterious effects that poor adjustment portends for the military personnel, their families and the general security of the country, and existing paucity of research especially in Nigeria where there is high number of military returnees in recent times, this paper empirically examined

1. The relationship between combat exposure, postdeployment social support and post-deployment adjustment among military returnees from Boko-Haram insurgency

2. whether combat exposure and post-deployment social support will have a significant joint influence on shortterm (6-12-months) adjustment among military personnel who had returned from the insurgency operation

3. We hypothesized that military personnel who experienced combat events but reported higher levels of post-deployment social support would experience better adaptation within one year of homecoming.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study represented a sample of the active duty military service personnel who had returned from the Boko-Haram operation in the north-east. A total of 322 military personnel were purposively sampled in a cross-sectional survey at six different military locations within Bauchi, Gombe and Plateau states. Demographic information revealed that 88(27.3%) were single, 226(70.2%) married while 8(2.5%) were divorced. Analysis on participants’ rank revealed that 70(21.7%) were private, 46(14.3%) Lance corporal, 92 (28.6%) corporal, 72 (22.4%) sergeant, 10(3.1%) staff sergeant 32(9.9%) belong to the other ranks. Concerning location of deployment, a total of 98(30.4%) were deployed to Bornu, 200(62.1%) went to Yobe, while 25(7.5%) went to other locations. Participants’ length of deployment ranged between 1 to 3 years and all of the participants have been deployed for more than two times for the operation.

Measurement

Demographic variables

Participants demographic data were obtained using a section of the questionnaire which requested information on age, rank, marital status, location of deployment, number of deployments and cumulative duration that each participant spend in the deployment.

Combat exposure

Combat exposure was measured using 7-item self-report combat exposure scale [15]. This a widely used measure that assess combat exposure specifically among military and paramilitary personnel. The scale was designed to measure all forms of combat situations such as wars, peacekeeping operations and terrorism. Items are rated on a 5-point frequency (1= no or never to 5= more than twelve times a week). Scores above the mean (Mean=18.39) indicates high combat exposure while scores below it indicates low combat exposure. The scale has been widely used among military veterans and found to be a sound psychometric measure with Cronbach alpha of .80 reported (Keane, Caddell, & Taylor, 1988). In Nigerian military population, the scale has been used and found to be good measure of combat exposure [4].

Post-deployment social support

Post-deployment social support was measured using the postdeployment social support scale [16], which is a 10-item selfreport measure that assess the level of emotional and instrumental assistance provided to a combatant by his family, friends and significant others upon returning from combat operations. Respondents indicated how much they agreed or disagreed with a set of statements related to social support after deployment. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with responses that ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Respondents were asked to “Please decide how much you agree or disagree with each statement and circle the number that best fits your choice. Sample questions include; “My family and friends understand what I went through in the Armed Forces”, “My family members or friends would lend me money if I needed it”. High scores indicate high social support while scores below the mean was used to infer low social support. Internal consistency as reported by the authors is 74 [16].

Post-deployment adjustment

Post-deployment adjustment was assessed using the Postdeployment Readjustment Inventory [17]. This is a 36-item selfreport measure on which respondents rated their agreement with how true they were able to adjust in four major domains of functioning since returning from deployment. These areas include adjustment to personal life (i.e., feeling like oneself again), family (i.e., feeling like a member of the family again), work (i.e., adjusting back to normal military work life), and cultural or social adjustment. All the items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all to 5 = completely. Participants were required to rate how true each of the items was related to them since their return from the operation. All items were scored and summed for a total score that could range from 36 to 180 with higher scores indicating greater or better postdeployment adjustment/ reintegration. The instrument has been widely used among military population and found to have very sound psychometric properties with cronbach alphas for the whole items (domains) ranging between .78 to .89, suggesting that, in line with past findings, moderate to high internal consistency of the scores (Blaise, Thompson & McCreary,2006).

Covariates

The covariates that were measured were selected because they represent factors that from a military standpoint were likely to be an added source of poor adjustment or have the potential to affect adjustment of military personnel in the society. These covariates included number of deployments and the cumulative length of deployment experienced by each veteran.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the relevant military authorities, the researchers approached the participants in their respective locations for screening interview. One of the researchers, a military officer, who actively participated in the insurgency operation, conducted the recruitment and screening exercise. The exercise took place six different military units that cut across Bauchi, Gombe and Plateau states and included only members who returned between six months and one year period. The reason for choosing military barracks within these states was due to the fact that a sizeable number of returnees resides within these zones for emergency purposes. All service members who met inclusion criteria were provided with a participant information sheet that contained a written description of the study including the study purpose, procedures, duration, risks, benefits, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participants who read and indicated interest were provided with a standardized questionnaire to fill under a conducive atmosphere.

In all, three hundred and twenty-two (322) respondents were purposively sampled across the six barracks. The reason for using purposive sampling was because the study specifically targeted only military personnel who actively participated in the counter insurgency operation and met other inclusion criteria. Also, due to the security situation in the country at the time of conducting this study and the nature of military job, the use of a randomized technique was practically impossible. Out of the four hundred questionnaires administered, only three hundred and twentytwo were properly filled. Questionnaires not properly filled were discarded. The study spans for about two weeks after which completed questionnaires were retrieved and subjected to data analysis.

The Pearson r correlation statistics was used to establish the relationships between study variables. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-20) was used to analyse data. Particularly, Hierarchical multiple regression statistics was used to test for the independent role of combat exposure and social support on postdeployment adjustment. The moderating effect of social support in the relationship between combat exposure and adjustment was also tested with hierarchical regression analysis.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Nigerian military authorities in the various locations sampled. Also, through the information provided on the questionnaire, respondents were informed that participation was voluntary and that the data obtained would be treated with absolute confidentiality. Participants were duly consented and briefed about the study before given questionnaires to fill. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, all the questionnaire copies administered were coded without any form of identification. Only relevant information were collected so as to avoid unnecessary invasion of their privacy. Participants were not subjected to any form of physical or psychological harm throughout the study period.

Results

(Table 1)

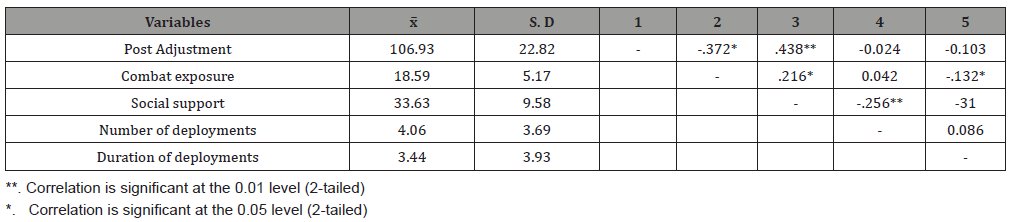

Result showing correlations between the study variables revealed that combat exposure was negatively associated with postdeployment adjustment (r= -.372; p<.05) while social support has a significant positive relationship with post-deployment adjustment (r= .438; p<.01). There was no significant relationship between number of deployments (r=-.024; p>.05), duration of deployments (r= -.103; p>.05) and post-deployment adjustment in this study.

Table 1: Zero-order correlation showing relationship between the independent, moderating and the dependent variable.

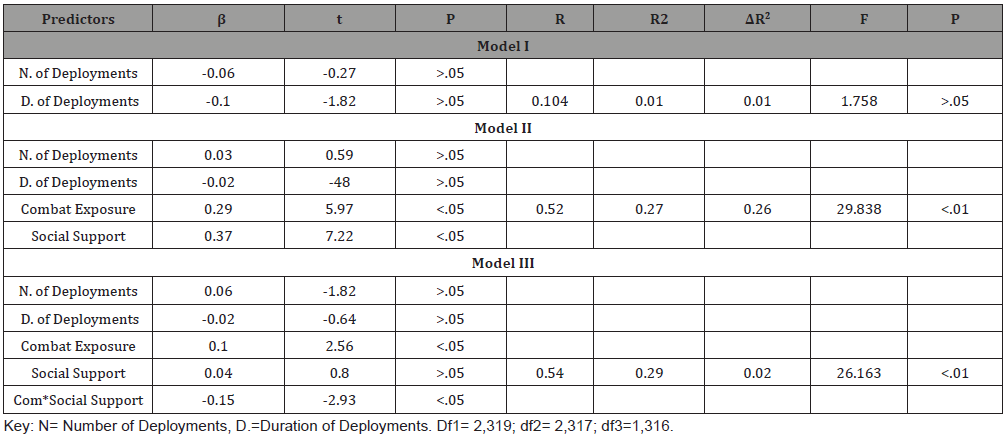

Table 2: Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis Showing the Moderating role of Social support in the influence of Combat Exposure on Postdeployment Adjustment.

(Table2)

Results on the above table reveals that, in the first model (model I), variables that has the potential to influence post-deployment adjustment were entered into the model as covariates and result indicated that number of deployments (β = -.06, t= -.27; p > .05) and cumulative length of deployment (β = -.10, t= -1.82; p > .05) has no independent nor joint influence [F(2,319 ) = 1.758; R2=.01; p>.05] on post-deployment adjustment. In the second model containing the main independent variable and moderator (model II), result indicated that combat exposure (β = 29, t= 5.97; p <.05) and post-deployment social support (β = .37, t= 7.22; p< .05) are significantly associated with and have joint influence [F(2,317 ) = 29.838; R2= .27; p<.01] on post-deployment adjustment. These influences are independent of number of deployments and duration of deployments (covariates) whose results were still insignificant. This establishment of a significant relationship implies that a moderation relationship may exist. Thus, in the third model (model III), the interaction term between combat exposure and social support was included and result indicted a significant interaction effect [ΔR2=.29, ΔF (1, 316) =.26.163p <.01; β= -.15, t= -2.93]. This result means that post-deployment social support moderated the negative influence of combat exposure on post-deployment adjustment of the military personnel.

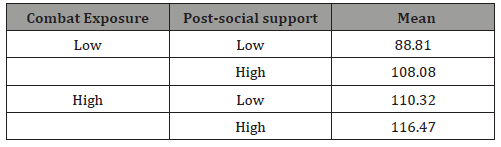

Table 3: Descriptive table showing the mean scores on post-deployment adjustment based on interaction between combat exposure and postdeployment social support.

To determine the direction of the moderation, a table of mean scores that shows the conditional effect of combat exposure on adjustment at two levels of social support is presented in (Table 3).

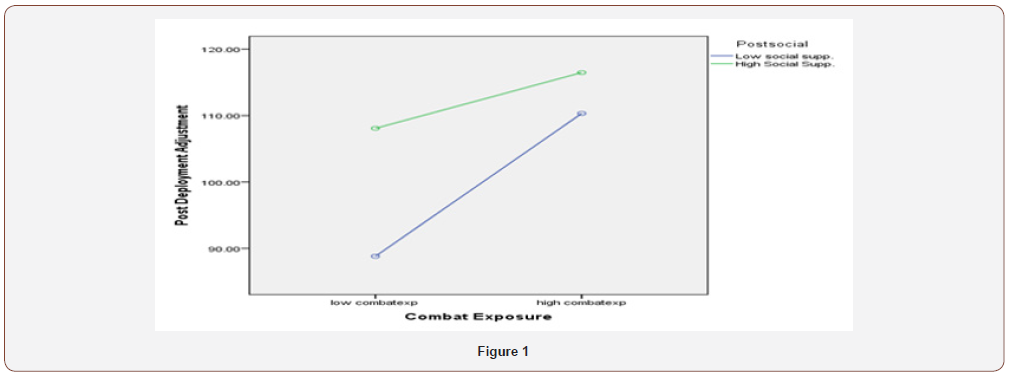

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, military combatants who were exposed to high combat but received high post-deployment social support reported better adjustment compared to those with high combat exposure but low social support. This result indicates that when there is high presence and provision of social support to returnes combatants, the traumatic experiences from combat exposure would be buffered and this will help the returnees adjust better in their families, work and society in general. A graphical illustration is shown in (Figure 1).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship and to ascertain if social support can predict better adjustment among Nigerian military personnel exposed to Boko-Haram insurgency. Specifically, the study investigated if there is significant relationship between combat exposure and post-deployment adjustment and whether this relationship can be moderated by post-deployment social support. From the results of correlational analysis, it was found that combat exposure has a significant negative relationship with post-deployment adjustment while social support was found to have a significant positive association with the criterion variable. This finding implies that the higher military personnel experience combat events during deployment, the poorer they will tend to adjust to societal life. Further results revealed a significant positive relationship between social support and postdeployment adjustment, implying that an increased in provision of post-deployment social support from family, military leaders and colleagues to returnee combatants will lead to immediate improvement in their adjustment to family, work and social life. In all, these results appear to align with [12] findings which reported that military veterans with long-term adjustment problems were those who experience additional stress, high combat events and poor social support network.

In addition, result revealed that combat exposure and social support are related and have a significant joint influence on shortterm post-deployment adjustment of returnee combatants. This result implies social support and combat exposure has the capacity to influence adjustment among military veterans. In other words, the availability of social support has a role in determining how returnee military combatants would adjust successfully into the society. This result also aligns with [12] which found poor support and experience of high combat events as key factors that affect adjustments among military personnel.

Interestingly, the negative association between combat exposure and post-deployment adjustment was moderated by social support in this study. Though exposure to high combat events was found to negatively impact post-deployment adjustment, social support moderated this impact. Specifically, personnel who reported high social support were found to adjust better irrespective of their level of combat exposure. On the other hand, those who reported lower support from family, friends and military leadership scored very low on adjustment, meaning that poor support to these personnel can affect their ability to quickly adjust and prepare for future challenges. The findings from this study provided empirical evidence that increased availability of emotional and instrumental support from military leaders and colleagues to traumatized combatants immediately after deployment can increase their ability to swiftly adapt and integrate fully into the society. Empirically, this result enjoys support from [10] which found support of family, friends and community members as having a significant restorative role in the adaptation of military combatants.

Conclusion

The paper therefore concluded that increased combat exposure can decrease soldiers’ ability to adapt in the society, especially in the first year of homecoming; however, providing emotional and instrumental support to them could buffer the negative impact of combat, thereby enhancing their adaptation to family, work and social life. Therefore, Nigerian military authorities, colleagues and friends of the personnel should always provide sufficient and timely support to soldiers and officers who are returning from the insurgency so as to help them adjust quickly and continue to render effectively, indispensable security services to the nation.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest

References

- Dai J, Yu H, Wu J, Wu C, Fu H (2010) Analysis on the association between job stress factors and depression symptoms. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 39(3): 342-346.

- Tackett DP (2011) Resilience factors affecting the readjustment of National Guard soldiers returning from deployment. Dissertation and Thesis: Antioch University Santa Barbara Paper, USA, pp. 119.

- Ameh AS, Kareem OT, Addulkarim IB, Olusupo S (2014) Posttraumatic stress disorder among Nigerian military personnel: findings from a post-deployment survey. Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2(1): 56-61.

- Abel J, Dagona ZK, Omoruri OJ, Dauda AS (2018) The wounds of terrorism among combat military personnel in Nigeria. Psychology Clinic Psychiatry 9(4): 425-429.

- Bolton EE, Litz B, Glenn MD, Orsillo MS (2002) The impact of homecoming reception on the adaptation of peacekeepers following deployment. Military Psychology 14(3): 241-251.

- Bowling UB, Shermian MD (2008) Welcoming them home: supporting service members and their families in navigating the tasks of reintegration. Journal of Psychological Research 39: 451-458.

- Johnson DR, H Lubin, R Rosenheck, A Fontana, S Southwick, et al. (1997) The impact of the homecoming reception on the development of posttraumatic stress disorder: the West Haven Homecoming Stress Scale. J Trauma Stress 10(2): 259-277.

- Cunningham GA, Weber AB, Roberts RL, Hejmanowski ST, Griffin DW, et al. (2014) Role of Resilience and Social Support in Predicting Postdeployment Adjustment. Mil Med 179(9): 979-982.

- Renée A, Megan B, Donald T, McCreary R (2006) The postdeployment reintegration scale: Association with organizational commitment, Jobrelated effect and career intensions. Defence Research and Development Toronto, Canada, pp. 192-196.

- Fontana A, Rosenheck R (1994) Trauma, change in strength of religious faith, and mental health service use among veterans treated for PTSD. J Nerv Ment Dis 192(2): 579-584.

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM (2009) Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depress Anxiety 26(8): 745-751.

- Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Southwick SM (2010) Structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and psychosocial functioning in veterans of operations enduring freedom and Iraqi freedom. Psychiatry Res 178(2): 323-329.

- Aremu AO (2014) Policing and terrorism: challenges and issues in intelligence. Orogun Stirling-Horden publishers, Nigeria.

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS (2007) Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295(9): 1023- 1032.

- Cesur R, Sabia JJ, Tekin E (2013) The psychological costs of war: Military combat and mental health. J Health Econ 32(1): 51-65.

- Katz LS, Cojucar G, Davenport CT, Pedram C, Lind C (2010) Postdeployment readjustment inventory: reliability, validity, and gender differences. Military Psychology 22: 41-56.

- King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Keane TM, Fairbank JA (1999) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans: Risk factors, war-zone stressors, and resilience-recovery variables. J Abnorm Psychol 108(1): 164-70.

-

Fredrick Sonter Anongo, James Abel, Binan Evans Dami, Aboh James Ogbole. Post-deployment Social Support Predicting Successful Adjustment among Nigerian Military Returnees from Boko-Haram Insurgency. 2(2): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000533.

Post-deployment, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Combatants, Returnee military, Coworkers, Obligation, Reintegration, Aggression, Cynicism, Barracks, Challenges, Incidentally, Domestic studies, Questionnaires

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.