Research Article

Research Article

Combat Exposure and Self-Efficacy Predicting Psychological Distress Among Military Personnel Exposed to Boko-Haram insurgency: The Moderating Role of Unit Support

James Abel1*, Fredrick Sonter Anongo2, Binan Evans Dami3 and Zubairu Kwambo Dagona4

1 Headquarters, 33 Artillery Brigade, Shadawaka Barracks Bauchi, Bauchi State, Nigeria

2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Nigeria

3Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Officer, International organization for Migration, Gambia

4Director, Centre for Peace and Conflict Management, Nigeria

James Abel, Headquarters, 33 Artillery Brigade, Shadawaka Barracks Bauchi, Nigeria.

Received Date: June 13, 2019; Published Date: June 28, 2019

Abstract

Military deployment come with a host of psychological challenges that affect soldiers’ quality of life and performance in future military operations. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression are conditions commonly associated with combat deployment among military veterans. Previous studies indicate that, a substantial number of military returnees from combat zones experience psychological distress, manifesting in form of anxiety and depression. However, these studies have provided little empirical evidence on the comorbidity in a single population of study. In Nigeria, for instance, there is still unfilled gap as to whether military personnel with combat-related PTSD would also experience depressive symptoms. In addition, little is known about the role of unit social support in the relationships between combat exposure, self-efficacy and the two dimensions of psychological distress. This study therefore investigated the role of combat exposure, self-efficacy on both anxiety and depression components of distress, and the moderating role of unit social support in the relationships between these variables among Nigerian military returnees from Boko-Haram insurgency. A cross-sectional survey method was adopted. Standardized questionnaires were used to collect data from 605 military returnees across six military units in three northern states. Pearson correlation and hierarchical multiple regression were used to analyzed the carefully retrieved data. Results revealed a significant negative relationship between combat exposure (r=.089;<.05) and self-efficacy (r= -.019; <.05) on anxiety. Unit social support showed a significant negative relationship with anxiety (r= -.120; .01) and depression (r= -.115; >.01). Results also indicated that combat exposure independently predicted anxiety (β= .06, t = 1.54, p <.05) and depression (β= .58, t = 1.54, p <.05), while self-efficacy did not predict neither anxiety (β= .01, t = -24, p >.05) nor depression (β= .09, t -24, p >.05). Further results indicated a significant interaction of unit social support and combat exposure on anxiety (ΔR2 = .021, β,.08, t, .47; p >.05) and self-efficacy (ΔR2 = .021, β,-.41, t, -2.00; p >.01) on anxiety component of psychological distress. The influence of self-efficacy on anxiety was low at high level of unit social support compared to when unit social support was low. This shows that providing immediate support during deployment to veterans could attenuate the negative effects of combat and self-efficacy on anxiety. Therefore, Nigerian military authority, colleagues and friends of the personnel should always provide sufficient support particularly during combat to boost solders’ confidence and reduce the deleterious effects of these risk factors on anxiety level of their personnel in order to promote effective performance.

Keywords: Combat exposure, psychological distress, unit social support

Introduction

Globally speaking, military personnel returning from combat operations are faced with several psychosocial challenges capable of affecting their personal functioning and productivity. In recent times, however, empirical reports have shown astronomical rise in psychological consequences of war among military veterans who return from combat operations [1-3]. According to Mirowsky and Ross, psychological distress is a state of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression. Upon return from combat engagement, the traumatic events experienced at combat may make many military veterans to become severely distressed due their impact on mood and healthy psychological functioning. For example, having experiences such as witnessing death, being ambushed, exposure to decomposing bodies and hostile fire may continue to intrude consciousness and be reexperienced many years after a soldier has returned from war the zone. This continuous intrusion could propel guilt, increase anxiety, affect postwar social life, promote suicidal thoughts and ultimately slip a veteran into unavoidable anxiety and depression problem [4].In addition, many of the veterans may lose interest in activities that were once pleasurable, experience loss of appetite, have problems concentrating, remembering details or making decisions, experience relationship difficulties and perform poorly in workplace. Unfortunately, such symptoms are antithetical to the warrior spirit and inconsistent with the behaviors and persona so highly valued in the military environment. Therefore, those who suffer may be reluctant to admit it or seek help, and may rather suffer in silence, numb the pain and ultimately suffer from unimaginable psychological distress.

Research has shown that between 13 to 32% of combat veterans are likely to experience psychological problems after homecoming [5,6]. Particularly, studies among American and Chinese Dai J, et al. [6] Cesur, Sabia & Tekin, South African [2] and Nigerian [7,8] combatants have shown that many military returnees from warzones suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder. In addition to PTSD, studies have also pointed out that exposure to unpleasant combat events can lead to symptoms of depression in military veterans Hoge CW, et al. [9]; Seal, Metzier, Gima, Bertenthal, Maguen, & Marmar. Findings from research exploring psychological distress in operation Afghanistan and Iraqi freedom revealed that, out of the 21.8% veterans who reported PTSD, 17.4% had a full diagnosis of depression Seal, et al. Unfortunately, soldiers who receive this diagnosis have been found to experience other problems, such as lack of job satisfaction, sick leave, increased substance use, negative work, marital conflict Galovski T and Lyons JA [10]; Vinakor, Pierce, Lewandowski, Romp, Hobfoll & Galea, cynicism and aggressive behaviours Meis LA, et al. [11], compromised immune system, risky health behaviors, cardiac-related problems, sleep difficulties and general burnout [1].

Notwithstanding these increased risks, research evidence has shown that in the face of comparable stressors like war trauma, majority of military and police personnel show impressive resilience and are unaffected by trauma while a minority exhibit significantly impaired functioning [12-14]. This suggests that people are not homogenous in their responses to stress and traumatic stress, and points to the direction that individual and social factors might be influential in the development of psychopathology or resilience. Thus, one important factor that emerged in literature on risk and protective factors is the salience of perceived control and its ability to influence psychological distress. Previous studies [14] have consistently demonstrated that the belief that military personnel have concerning their ability or general capacity to handle stressful situations has a significant role in stressful outcome. Perception in one’s ability to successfully execute a given task, has been found to influence performance and mental health [15]. Bandura A [16] defined self-efficacy as the “belief in one’s ability or capability to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment”. According to Bandura A [16] an individual thoughts and beliefs about a traumatic experience play a significant role in influencing behaviour including mental functioning and psychological adjustment to trauma. Military personnel with high perception concerning personal capacity to manage the stress generated by Boko-Haram encounter may mobilize the necessary psychological resources that prevent distressing thoughts, feelings and behaviours, making them less likely to experience psychological strain. Conversely, those who show poor control to the event and see themselves as possessing low abilities may experience adverse mental effect including posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. This notion is supported by Bandura, wherein he asserted that people who display low self-efficacy when confronted with trauma may become extremely anxious and display unpleasant negative emotions that may lead to depression.

Interestingly, availability of a healthy and supportive social network has been found to buffer the negative impact of trauma on distress. Although social support has been widely studied and linked with PTSD and to a lesser degree, depression, less research attention has been given to military unit social support [17,18]. This refers to the instrumental and emotional assistance and encouragement provided by military leaders and unit members to veterans during deployment [19]. This could be in form of material or emotional support that military leaders and colleagues provide to a veteran during deployment. This support is very important to restore tranquility after participating /exposure to hostilities that are imminent of any combat environment. Thus, with high availability of such support, military personnel who encounter these events may have positive coping thoughts, develop more confidence in withstanding the challenges and become less affected by them. According to Schwarzer R and Knoll N [20] availability of social support helps in building self-confidence and modification of coping ability to trauma. This suggest that, with support, selfefficacy may become an insignificant factor in distress. Thus, in military population, high level of support from military units have been shown to protect against the development of PTSD while lack of it has been associated with higher symptoms [21].

Unit support is very important to psychological health because it is the first form of support that military personnel need to have from their military environment to restore tranquility. During combat engagement, military personnel may need some financial, emotional and informational support from their unit leaders and colleagues. Perception that this support will be available may reduce the negative impact of the experiences and low coping abilities on the development of psychological problems. Having a sense of social support in form of discussing one’s distressing deployment experiences with others, including mental health service providers and unit members can reduce the deleterious effect of trauma on psychological health and promote healthy adjustment of a combatant [22].

Examining unit social support became imperative considering the perceived unavailability or inadequate support that most Nigerian soldiers claimed was lacking during the war. This variable has not received sufficient attention as majority of research have focused exclusively on postdeployment social support. In foreign military population, only Polusney MA, et al. [23] attempted to examine the role of unit support in trauma, but like many others, their research was limited to PTSD. Therefore, in Nigeria where military personnel have had repeated encounters with the dreaded Boko-Haram Insurgents with potentially traumatic experiences (being shot at, witnessing human deaths, being ambushed, being exposed to improvised explosive devices (IEDs), experiencing severe injuries amongst others, examining the moderating role of unit social support in preventing psychological distress became necessary. The imperativeness of this is premised research findings revealing that combatants who lack sufficient support and social cohesion find it difficult to adjust even long after deployment [22,24-28]. In addition to lack of domestic research on unit social support, most of the documented studies in military population have focused exclusively on the anxiety (PTSD) component of distress [7,8]. Thus, understanding the role of combat exposure and self-efficacy in both anxiety and depression is lacking particularly in Nigerian setting.

Given the importance of unit social support in distress, and the imminent deleterious effects of psychological distress to the military and security of the populace, this paper examined: (1), the relationship between unit social support, combat exposure and psychological distress- anxiety and depression; (2),whether combat exposure and self-efficacy would predict all the dimensions of psychological distress (anxiety and depression); (3) whether unit social support would moderate the relationship between combat exposure, self-efficacy and two dimensions of psychological distress in military returnees from Boko-Haram insurgency in the North-east.

Method

Design/ Participants

The study adopted a cross-sectional survey, utilizing ex-post facto design to examine association among study variables that were not actively manipulated. Participants represented a sample of the active duty military personnel who had returned from the Boko-Haram operation in the north-east. Six hundred and five (605) returnees were purposively recruited at six military locations/ Barracks across three Northern states of Bauchi (33 Artillary Brigade, 211 Demo Battalion and Nigerian Army school of Armour), Gombe (301 General support Artillery) and Plateau states (3 Armour Division Garrison and 82 battalion). Demographic information revealed that the age range was between 18-56. Concerning participants’ religious affiliation, 445(73.5%) were Christians, while 160(16.5%) were of Islamic religion. Regarding marital status, a total of 490 (80.90%) were married,115(11.1%) were single military personnel. Analysis on participants’ rank revealed that 130(21.5%) were private, 160 (26.4%) Lance corporal, 100 (16.5%) corporal, 117 (19.3%) sergeant, 56(9.2%) staff sergeant while a total of 42 (6.9%) belong to the other ranks.

Instruments

Demographics and contextual variables

Demographic variables measured in this study included age, marital status, rank, religion, educational qualification, family history of mental illness while contextual variables were number of deployments and cumulative length of deployment. Combat exposure. Combat exposure was measured using 7-item self-report combat exposure scale Keane, Caddell, & Taylor. This a widely used measure that assess combat exposure specifically among military population. The scale was designed to measure all forms of combat situations such as wars, peacekeeping operations and terrorism. Items are rated on a 5-point frequency (1= no or never to 5= more than twelve times a week). High scores indicates high combat exposure. The scale has been widely used among military veterans and found to be a sound psychometric measure with Cronbach alpha of .80 reported Keane, Caddell, & Taylor. In Nigerian military population, the scale has been widely used and established as a good measure of combat exposure [3]. Unit social support. Unit social support was assessed using a 12-item self-report instrument developed by Vogt, Smith, King, King, (2012). This instrument measures the amount of instrumental and emotional assistance that military personnel receive from unit leaders and colleagues during deployment and is scored using the 4-point Likert scale. High scores (44.9) indicates high unit social support while scores below the mean infers low support. The scale has demonstrated robust psychometric properties in studies involving military population. In this study, the established internal consistency was .94

Self-efficacy. A 30-item self-efficacy scale Maddox, Mercandante, Prentice-Dunn, Jacobs and Rogers was adopted and used to assess participants’ self-efficacy in the study. The instrument measures peoples’ perception about their personal ability and capacity to deal with stressful challenges. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale and higher scores indicates high self-efficacy. In terms of utility and psychometric properties, Ayodele found it a good measure of selfefficacy in civilian and non-civilian population.

Psychological Distress. Psychological distress was assessed using a 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). This has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of the dimensions of depression, anxiety, and stress separately but also taps into a more general dimension of psychological distress. Scores for depression, anxiety and stress are calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items and multiplying them by two. Items are rated on a 4-point scale showing how much each particular statement applies to the individual. Each of the components is interpreted separately using a cut-off mark ranging between 8-9 for anxiety, 10-13 for depression, 15-18 for stress. The scale has been widely used and found to be a good measure of psychological distress in both clinical and general population.

Procedure

Data collection began as soon as approval was granted by relevant military authorities in the various locations/barracks. One of the researchers, a military officer, who actively participated in the insurgency operation, conducted the recruitment and screening exercise. The exercise took place in six different military units that cut across Bauchi, Gombe and Plateau states. The reason for the choice of these locations was due to the huge presence of returnees domiciled within these states. Available and eligible returnees who met inclusion criteria were provided with a participant information sheet that contained a written description of the study including the study purpose, procedures, duration, risks, benefits, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participants who read and indicated interest were provided with a standardized questionnaire to fill under a conducive atmosphere.

In all, six hundred and five (605) respondents were purposively sampled across the six barracks. The reason for using purposive sampling was because the study specifically targeted only military personnel who actively participated in the counter insurgency operation and met other inclusion criteria. Also, due to the security situation in the country at the time of conducting this study and the nature of military job, the use of a randomized technique was practically impossible. Out of the seven hundred questionnaires administered, only six hundred and five were properly filled and returned. Questionnaires not properly filled were discarded. The study spans for about two weeks after which completed questionnaires were retrieved and subjected to data analysis. The Pearson r correlation statistics was used to establish the relationships between study variables. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-20) was used to analyse data. Particularly, moderated multiple regression statistics was used to test for the independent and moderating influence of unit social support in the relationship between combat exposure, self-efficacy and psychological distress dimensions.

Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Nigerian military authorities in the various locations sampled. Also, through the information provided on the questionnaire, respondents were informed that participation was voluntary, and that the data obtained would be treated with absolute confidentiality. Participants were duly consented and briefed about the study before given questionnaires to fill. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, all the questionnaire copies administered were coded without any form of identification. Only relevant information were collected so as to avoid unnecessary invasion of their privacy. On the issue of risk, no participant was meant to incur any physical risk throughout the study. However, the possibility of minimal economic and social risk, such as stigma and impact on career prospects, made the researchers to adhere strictly to the principle of confidentiality. No name or any obvious means of identification was required. Participation for the study required no cost and was voluntary and the findings would recommend for implementation to improve the wellbeing of the officers.

Results

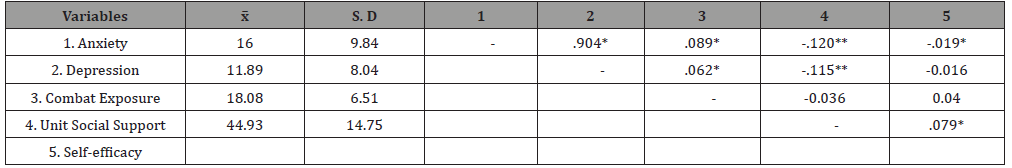

Initial exploratory correlations between the study variables revealed that combat exposure was negatively associated with the anxiety (r=.089;<.05) but not the depression (r=.062; >.05) component of psychological distress. Self-efficacy had a negative relationship with anxiety (r= -.019; <.05) but was not related to depression (r=-.016; >.05). Unit social support indicated a significant negative relationship with anxiety (r= -.120; <.01) and depression (r= -.115; >.01). There was also a significant positive relationship between unit social support and self-efficacy (r= -.079; <.05) (Table 1).

Table 1:Zero-order correlation showing relationship between the independent, moderating and the dependent variables (Anxiety and Depression).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

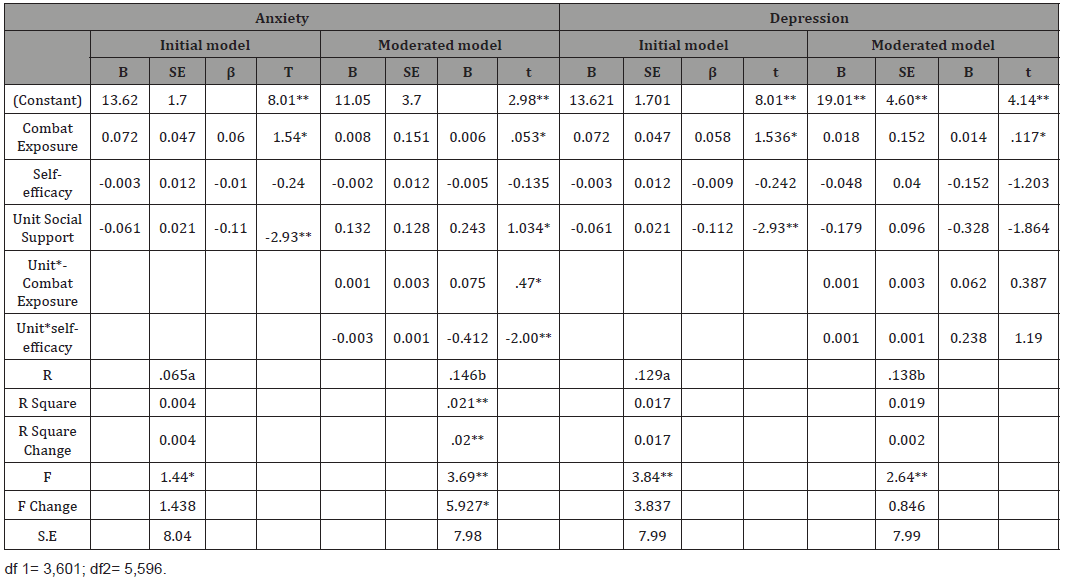

Table 2:Two-step moderated regression analysis showing the moderating influence of unit support on the relationship between combat exposure, self-efficacy and psychological distress (Anxiety and Depression).

Results in (Table 2) explains the predictive role of combat exposure and self-efficacy on the two dimensions of distress (Anxiety and depression) and the moderation role of unit social support in the relationship between the independent variables and the dimensions of the dependent variable. On individual influence, combat exposure independently predicted anxiety (β= .06, t = 1.54, p <0.05) and depression (β= .58, t = 1.54, p <.05). However, self-efficacy did not predict neither anxiety (β= .01, t = -24, p >.05) nor depression (β= .09, t -24, p >.05). Under the anxiety model, we tried to ascertain whether unit social support would moderate the relationship between combat exposure, self-efficacy and symptoms of Anxiety and depression. To test the model, the independent variables and the moderator (Combat exposure, self-efficacy, unit social support) were regressed on anxiety and depression scores. Result indicated that combat exposure, self-efficacy and unit support had a significant joint relationship with anxiety component and accounted for 4% of the variance in the symptoms of the disorder, R2 = .04, F (3, 601) = 1.44, p <.05. This means that a moderating relationship may exist among the variables. To test for moderation, the interaction term between unit social support and combat exposure, unit social support and self-efficacy were included into the second model and result indicated a significant interaction effect, revealing that unit social support moderated the influence of combat exposure (ΔR2 = .021, β,.08, t, .47; p >.05) and self-efficacy (ΔR2 = .021, β,-.41, t, -2.00; p >.001) on anxiety.

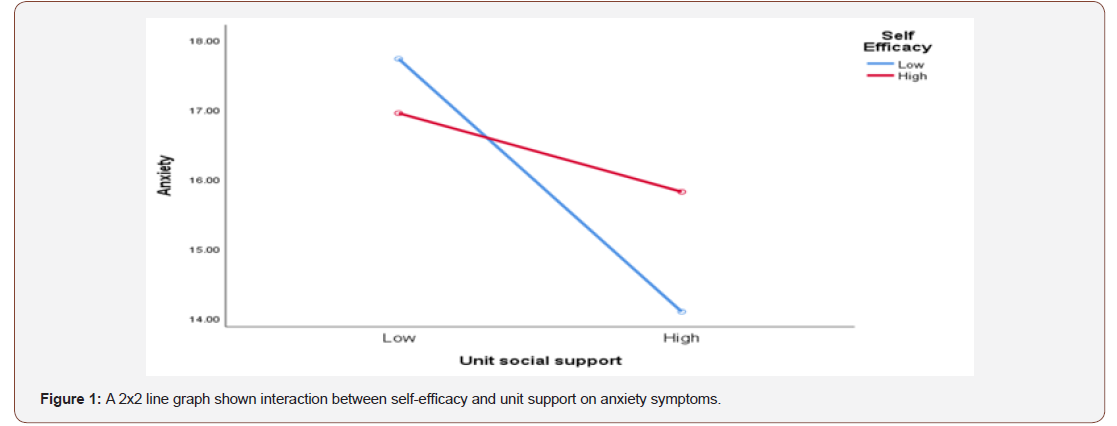

However, in the model under depression, though all the independent variables showed a significant joint relationship with depression R2=.017, F (3,601) = 3.84, p <.05, there was no interaction effect (ΔR2 = .019, ΔF (5, 596) = .85p > .05). Interactions between combat exposure and unit social support (β = 0.62, t = 39, p >.05), self-efficacy and unit social support (β= .24, t = 1.19, p >.05),) on depression were all statistically insignificant. As shown in (Figure 1), the influence of self-efficacy on anxiety was low at high level of unit social support compared to when unit social support was low. Though personnel with low self-efficacy reported lower symptoms compared to those with high self-efficacy at the initial stage, when unit support became low, it reversed this relationship. Thus, at low unit support, military personnel with low coping selfefficacy reported higher symptoms of anxiety compared to those with high self-efficacy. This implies that when there is lack or low availability of support to military veteran during combat, it will increase their vulnerability Anxiety problems.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to examine relationship between unit social support and psychological distress (Anxiety and Depression), determine whether combat exposure and selfefficacy would predict anxiety and depression and to determine whether unit social support would moderate the relationship between combat exposure, self-efficacy and psychological distress among Nigerian military returnees from Boko-Haram insurgency in the North-east. From the associations found between unit social support and the dimensions of psychological distress, result of a multiple correlation revealed a significant negative relationship between unit social support and the two dimensions of anxiety and depression. Conversely, there was a significant negative relationship between unit social support and self-efficacy in this study. The findings from this study provided empirical evidence that increased availability of emotional and instrumental support from military leaders and colleagues to traumatized combatants during deployment can increase their ability to manage combat events and decrease vulnerability to Anxiety and depression. This suggests that providing relevant support to military personnel while in theatre may lead to a consequent reduction in their experience of psychological distress.

In addition, combat exposure predicted all the dimensions of psychological distress. This implies that exposure to combat events has the potential to affect both anxiety and depressive symptoms in military veterans. This finding is in line with Seal, et al, which found that out of 21% American veterans diagnosed with PTSD,17.4% had a full diagnosis of depression. However, self-efficacy was negatively related to anxiety but did not predict neither anxiety nor depression in the repression model. This imply that though poor self-efficacy may increase anxiety, it has less strength to predict any of the dimensions of distress in this population. Unit social support was also found to moderate the negative effects of combat on anxiety among the personnel. Though exposure to high combat events was found to negatively impact anxiety, high availability of support from colleagues and military leaders attenuated this impact. Thus, despite the high stress orchestrated by the exposure, individuals who received high support at combat appeared to remain calm and unaffected behaviorally or emotionally and tended to report lower symptoms of anxiety. In all, these findings may support the findings of Polusyet MA, et al. [22] which found that American military veteran with low unit social support reported high posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Similarly, unit social support also moderated the effect self-efficacy on anxiety such that at low level of unit support, self-efficacy was inversely related to manifestation of anxiety problem. This implies that when there is lack or low availability of support to military veteran during combat, it will it will increase their vulnerability to anxiety. The findings enjoys support from Karney BR, et al. [15] who found that social support has significant role in performance and mental health. This paper therefore concludes that combat exposure can affect both anxiety and depression and that unit social support can help reduce the negative impact of combat and self-efficacy on manifestation of psychological distress among military personnel in Nigeria. Therefore, military authorities should provide sufficient support particularly during combat to boost solders’ confidence and reduce the deleterious effects of these risk factors on anxiety level of their personnel so as to enhance their effective performance.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest

References

- Tackett DP (2011) Resilience factors affecting the readjustment of National Guard soldiers returning from deployment. Dissertation and Thesis Submitted to Antioch University Santa Barbara, pp: 119.

- Cornell MA, Omole O, Subramaney U, Olorunju S (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder and resilience in veterans who served in South African border. Afr J Psychiatry 16(6): 16-33.

- Abel J, Dagona ZK, Omoruri OJ, Dauda AS (2018) The wounds of terrorism among combat military personnel in Nigeria. Psychology Clinic Psychiatry 9(4): 425-429.

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Drescher KD (2015) Spirituality factors in the prediction of outcomes of PTSD treatment for U.S. military veterans. J Trauma Stress 28(1): 57-64.

- Ann M, Nora G (2012) Peer social support and combat-related trauma among returning operation Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Advances in Social Work 13(3): 586-602.

- Dai J, Yu H, Wu J, Wu C, Fu H (2010) Analysis on the association between job stress factors and depression symptoms. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 39: 342- 346.

- Okulate GT, Jones OBE (2006) Post-traumatic stress disorder, survivor guilt and substance use-a study of hospitalized Nigerian army veterans. S Afr Med J 96(2): 144-146.

- Ameh AS, Kareem OT, Addulkarim IB, Olusupo S (2014) Posttraumatic stress disorder among Nigerian military personnel: findings from a post-deployment survey. Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2(1): 56-61.

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, Mc Gurk D, Cotting DI, et al. (2004) Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan: mental health problems and barriers to care. N Engl J Med 351(1): 13-22.

- Galovski T, Lyons JA (2004) Psychological sequelae of combat violence: A review of impact of combat violence on PTSD on veterans family and possible intervention. Aggression and Violent Behaviour 9(5): 477-501.

- Meis LA, Erbes CR, Polusney MA, Compton JS (2010) Intimate relationships among returning soldiers: mediating and moderating roles of negative emotionality, PTSD symptoms and alcohol problems. J Trauma Stress 23(5): 546-572.

- Nugent NR, Saunders BE, Williams LM (2009) Post-traumatic stress symptom trajectories in children living in families reported for family violence. J Trauma Stress 22(5): 460-466.

- De Roon Cassini TA, Mancini AD, Rusch MD, Bonanno GA (2010) Psychopathology and resilience following traumatic injury: A latent growth mixture model analysis. Rehabil Psychol 55(1): 1-11.

- Galatzer Levy IR, Madan A, Neylan TC, Henn Haase C, Marmar CR (2011) Peritraumatic and trait dissociation differentiate police officers with resilient versus symptomatic trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Trauma Stress 24(5): 557-565.

- Karney BR, Ramchand RC, Osilla K, Barnes CL, Burns RM (2008) Predicting the immediate and long-term consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and traumatic brain injury in veterans of operation enduring freedom and operation Iraqi Freedom: in Tanielian T, Jaycox LH(eds.), Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery, Europe.

- Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (10th Edn.), Freeman WH and Company (Edr.), New York.

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(5): 748-766.

- Ozer E, Best SR, Lipsey TL, and Weiss DS (2003) Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 129(1): 57-73.

- King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, Samper RE (2006) Deployment risk and resilience inventory: a collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology 18: 89-120.

- Schwarzer R, Knoll N (2007) Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: a theoretical and empirical review. International Journal of Clinical Psychology 42: 243-252.

- Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, Amoroso P, Kane R, Heeren T, et al. (2006) Neuropsychological outcomes of army personnel following deployment to the Iraq war. JAMA 296(5): 519-529.

- Cunningham GA, Weber AB, Roberts RL, Hejmanowski ST, Griffin DW, et al. (2014) Role of Resilience and Social Support in Predicting Postdeployment Adjustment. Mil Med 179(9): 979-982.

- Polusney MA, Erbes CR, Murdoch M, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, et al. (2011) Protective and risk factors for new-onset posttraumatic stress disorder in National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. Psychol Med 41(4): 687- 698.

- Tsai J, Harpaz Rotem I, Pietrzak R H, Southwick SM (2012) The role of coping.

- Braidley K, Vasterling JJ, Proctor PS, Constans IJ, Friedman JM (2007) PTSD symptoms, Life event, and unit cohesion in U.S. Soldiers: Baseline findings from the neurocognition deployment health study. J Trauma Stress 20(4): 495-503.

- Philippe FL, Lecours S, Beaulieu Pelletier G (2009) Resilience and positive emotions: Examining the role of emotional memories. J Pers 77(1): 139-176.

- Vinokur AD, Pierce PF, Lewandowski Romps L, Hobfoll SE, Galea S (2011) Effects of war exposure on air force personnel’s mental health, job burnout and other organizational related outcomes. J Occup Health Psychol 16(1): 3-17.

- Vogt DS, Samper RE, King DW, King LA, Martin JA (2008b) Deployment stressors and posttraumatic stress symptomology: Comparing Active Duty and National Guard/Reserve personnel from Gulf War I. J Trauma Stress 21(1): 66-74.

-

James Abel, Fredrick Sonter Anongo, Binan Evans Dami, Zubairu Kwambo Dagona. Combat Exposure and Self-Efficacy Predicting Psychological Distress Among Military Personnel Exposed to Boko-Haram insurgency: The Moderating Role of Unit Support. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 2(2): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000532.

Combat Exposure, Self-Efficacy, Psychological Distress, Anxiety, Depression, Regression

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.