Short Communication

Short Communication

Avoiding Traditional Psychoanalysis: An insolence Founded on Misconstruction

Saeed Shoja Shafti, Department of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Iran.

Received Date: June 17, 2019; Published Date: July 03, 2019

Summary

Status quo of psychoanalysis and similar insight-oriented techniques is not alike in developed and developing nations, due to a number of cultural or scholastic reasons, along with shortage of required facilities. The outcome of such a state of affairs might be nothing except than nearly complete ignorance of this genuine exploratory technique and substituting it with more superficial psychotherapeutic approaches like cognitive therapy, behavior therapy and etc., which operate just at the conscious and subconscious levels of mind. Furthermore, decline of enactment of psychotherapy by psychiatrists in developed societies possibly will be even more discouraging for therapists in undeveloped ones. In this article, which is devoted mainly to developing, traditional or conservative states, a number of obstacles against training and development of applied (clinical) psychoanalysis and related procedures has been discussed concisely.

Keywords: Psychoanalysis; Psychodynamic psychotherapy; Developing societies; Developed societies; Core curriculums

Short Communication

Psychoanalysis and its modified versions like psychodynamic psychotherapy constitute important components of modern psychotherapy. Psychodynamic theories stress that early childhood experiences are crucial in shaping the personality. In psychodynamic approaches unconscious conflicts are explored and the insight gained aims to change patients’ maladaptive behavior. The main goals of such kind of psychotherapies are symptom relief and personality modification through exploration of the unconscious. So, the relationship between the therapist and patient is crucially important. Therapies can be offered on an individual, couple, group and therapeutic residential community basis. Psychodynamic psychotherapy has been shown to be a highly efficacious treatment in a range of psychological disorders but patient selection for therapy is important, with consideration of psychological mindedness and a concern with the antecedents as well as the relational contexts of the presenting problem being key [1].

Generally, for trainees in psychiatry, an understanding of psychological therapies is important for many reasons. Early exposure to psychotherapy is important for trainees to decide whether they want to specialize in this field. For psychiatrists who do not go on to specialize in psychotherapy, experience of this area also represents an essential part of their training. For all psychiatrists there is likely to be a psychological component to the presentations of most patients seen in mental health services, and for some there will be significant transference and countertransference reactions. To care for these patients, doctors will need to be able to understand and deal with these factors appropriately. Psychodynamic factors are also important in many interactions within mental health teams, both community- and ward-based. Doctors who can perceive these, and adapt to them, will make better leaders within these teams. Another relevant factor relates to appropriate referrals for psychological therapies. One model of psychological therapy does not fit every problem, or every patient. Psychiatrists will frequently be responsible for assessing and diagnosing a patient, and deciding on a course of treatment, which may be biological, psychological or both. To assess and refer appropriately the treating psychiatrist must understand the indications for a particular therapy and be able to have an idea of its likely success in a particular patient. But training in psychotherapy is likely to be more consuming of resources than other areas of postgraduate study in psychiatry. For example, an area such as psychopharmacology can be learnt in a more self-directed way, relying mainly on written information, whereas the main activity of psychotherapy training is seeing patients, and being supervised in their treatment. With the financial challenges of recent times, mental health services as a whole are likely to be asked to make significant cuts to services. Psychotherapy, particularly longer models, may be a target for reduced services, leading to a further restriction in the availability of training [2].

Psychoanalysis, as second historical revolution in psychiatry, first systematic psychotherapeutic approach, and an essential exploratory tool for study of deeply rooted unconscious mental processes plays a key role. But in spite of its central position among different styles of psychotherapy, its situation as training curriculum is not the same in developed and developing societies, due to a number of clashes between its various theoretical aspects and usual cultural ideals. Some aspects of this topic have been discussed previously in another article regarding process of appearance and progression of psychoanalysis in Iran, as a prototypical developing society in the region [3]. For sure, such a historical process could have more or less similar characteristics and /or problems around the world, particularly with respect to conservative societies. The aforesaid clashes are based on a mixture of valid and non-valid believes, hold by superintendents and/or psychotherapists.

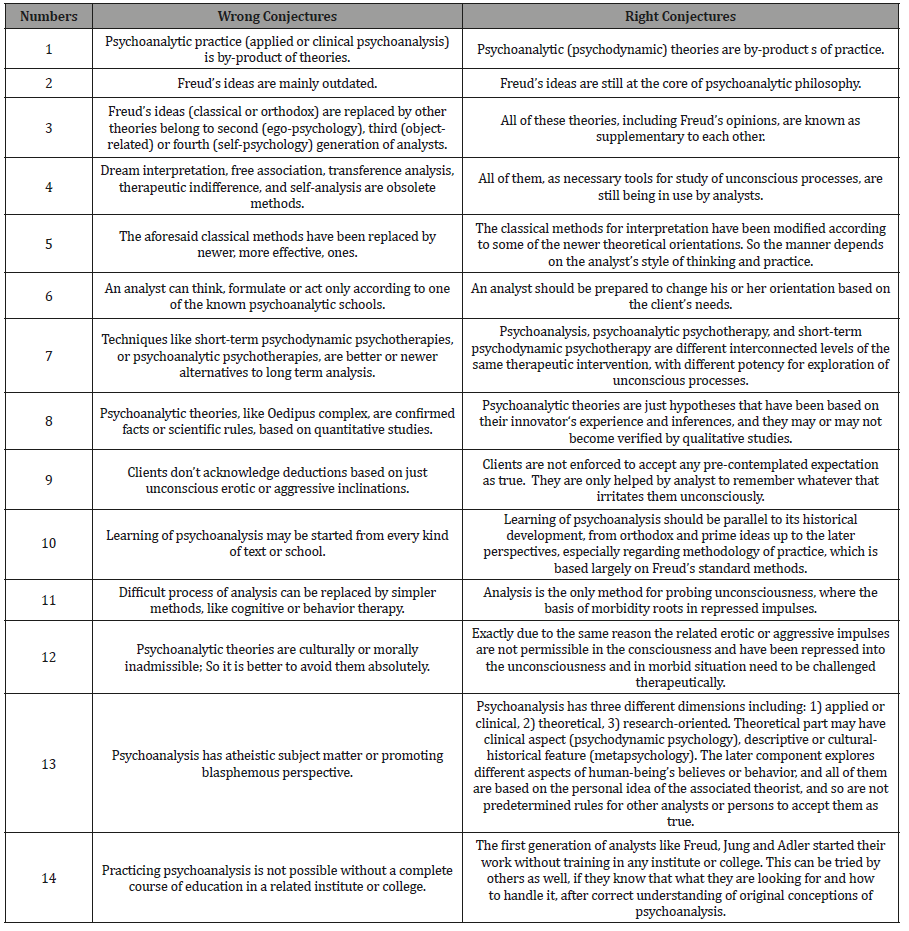

The justifiable part of this challenge involves the necessity of special kind of setting, lack of suitable supervision or qualified supervisors, troubles regarding monetary issues and financial assistance or coverage by insurance companies, and above all, lack of qualified institutes for training skillful analysts. The mistaken part of that clash is based mainly on misinterpretation or distorted inference of psychoanalytic theories or overindulgence in them without any experimental or practical proof or perspective. The end result of such a disturbing circle could be nothing except than general ignorance of this deeply investigative method and replacing it with more superficial individual psychotherapeutic methods like Cognitive therapy, behavior therapy and etc., which basically never penetrate so deep into the mental strata and act only at conscious and subconscious levels. While psychoanalysis probe absolutely in the district of unconsciousness, with numerous swinging in the midst of conscious and subconscious levels, all of the other methods starting from conscious layer and reside constantly there or operate maximally at the subconscious level of mind. For a therapist who believes in unconscious processes this means nothing than obvious shortcoming of therapeutic intervention in instances where deep analytical method is mandatory. Although some believe that long-established cultural values or slow psycho-social stage of development may play an important role against progression of psychoanalysis in developing societies, it cannot be ignored that wrong or distorted understanding of the matter is not an unimportant subject (Table 1). Why such a wrong comprehension is common among psychotherapists of developing societies? It seems to be rather due to deviation from fundamental literature and particularly circumnavigating Freud’s basic and pragmatic writings. Psychoanalysis had been introduced to the world by ‘studies on hysteria ‘, valuable work of Freud S & Breuer J [4], and then in around two decades extended overseas up to America. The aforesaid book with a clear medical aspect for treatment of psychoneuroses (hysteria, phobia and obsession), though apparently dated, is still the opening point of teaching and practicing analysis, and this is the same as regards other practical works of Freud as well [5-12].

Table 1: Some common erroneous conjectures about psychoanalysis.

Touching and probing unconsciousness is not practicable without methodical exploration and interpretation of associations on coach, and such a skill is not attainable without resorting to original works. An enthusiastic psychotherapist must be able to differentiate between what may enhance potentiality for interpretation and construction and what that may just increase reader’s psychological knowledge. So, the first task of every psychotherapist is broadening his or her personal insight. Slowmoving and unmethodical progression of clinical psychoanalysis and its modified versions in conservative societies’ scholastic centers, in spite of availability of necessary resources, shows that simple knowledge or resource is not enough for founding a method. In an unsuccessful forced training program for persuading a small group of psychiatric residents for starting classical method of analysis, lack of enthusiasm and venture were more apparent than lack of setting and knowledge, while some of them had formerly educated additional hours of theoretical lessons in other academic centers, and had stated frankly their inclination for performing analysis.

Exaggerated interest to theoretical aspects of psychoanalysis, instead of its pragmatic aspects, could demonstrate an inaccurate understanding of the subject by them. This state of affairs proves once more that wishing and knowledge are not equivalent to capability and talent, and motivation is something different from enthusiasm. Showing a sufficient amount of endeavor for performing a job, adequate curiosity for complete study of known references [13-18], or prominent interest for clinical evaluation of its effectiveness can reflect interior passion of trainees. Moreover, their expressed inclination to applied psychoanalysis was not easily differentiable from other methods of psychotherapy. This shows that untimely training, as like as unsystematic approach, may not attain the desired goals. It is understandable that how a psychiatric resident may become easily confused in facing with a large number of psychotherapeutic methods during the educational curriculum. So, it takes time for him or her to become familiar with all of them and to choose among them the technique which is best fitting with the participant’s character and objectives, a hope that, however, may never be fulfilled in numerous cases. So, acquiring knowledge regarding different styles of psychotherapy during collegiate era possibly will conserve time and energy in post-graduation years. In addition, there are a number of crucial dissimilarities between psychotherapy and psycho-pharmacotherapy, including speed of response, intervening variables regarding therapist’s personality or cultural background and patient’s motivation or conformity, which may altogether stop absolutely psychiatric resident or graduated psychiatrist from perusing psychotherapy throughout his or her profession. While in developed societies such a dilemma has been compensated mainly by other experts in the sphere of mental health, such a solution does not seem to be achievable easily in developing societies, since their position in this regard has not been effectively recognized. Besides, their training is not independent from general educational policies of their society. On the other hand, since practicing psychotherapy in developed societies, as a basic therapeutic instrument, was widespread before emergence of psycho-pharmacotherapy, so existence of some promoting sociocultural aspects in this regard in that societies is plausible. But such an advantage in developing societies that want to promote psychotherapy, years after practicing psycho-pharmacotherapy, is not as easy as the developed ones, especially with respect to the abovementioned different speed of achievement between these dissimilar methods. It must not be ignored that practicing psychotherapy, firstly must be acknowledged by psychiatrist as something comparable to a full job, not an overtime task or option, and secondly demands additional insight for accounting of unconscious aspect of morbidity plus its phenomenological aspect. So, modification of clinical perspective of learners, as well, is very important, if educational system really wants to promote deep psychotherapeutic methods in training curriculum. Moreover, non-compulsory feature of psychotherapy, in opposite to obligatory aspect of psycho-pharmacotherapy in medical practice is an important reason against its development. Decreasing rate of practice of psychotherapy by psychiatrist in developed societies also can be dissuading for interested therapists in developing countries. According to Chisolm MS, from department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, while psychotherapy has long been an integral treatment modality for patients with psychiatric conditions, recent evidence suggests that the practice of psychotherapy by psychiatrists has greatly diminished. Between 1996 and 2005, the percentage of psychiatry office visits involving psychotherapy decreased from about 44% to 29%, a 35% reduction in less than 10 years. Although the increasing availability of medications to treat psychiatric disorders has played a role in this decline, it is not the only factor. This essay reviewed the multiple forces affecting this shift and highlights the limited knowledge base regarding the impact of this change on patients. The aforesaid article concluded with a call for research to prevent unintended and potentially harmful consequences to patients and to inform the continued role of psychotherapy in residency education [19].

Certainly, this condition is not in harmony with the academic aspiration of integrating psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy in training curriculums of medical schools, particularly in developing countries. Amid this, psychoanalysis has the most defenselessness. Flawed academic curriculums and lack of appropriate setting or qualified supervisor for teaching psychoanalysis or psychoanalytic psychotherapy to psychiatric residents or zealous graduated psychiatrist or other capable psychotherapists, alongside lack of official psychoanalytic association, institute, and psychotherapy departments in the school system are amongst the major impediments in developing countries that prevent promotion of applied or clinical psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy among talented psychotherapists, including psychiatrists. The only factor that can overcome such unwanted impediments is the passionate of insightful therapists. If a therapist knows what to do and how to handle the process of analysis, then neither of the abovementioned personal or social barriers can prohibit him or her from probing unconsciousness. If the list of references configures according to the historical process of development of psychoanalysis, then no misrepresentation or distorted assertion may devastate his or her enthusiasm. Bypassing Freud and his methodology, or failure to distinguish between his pragmatic hints and metapsychological remarks has founded a big dilemma in the course of training or practicing clinical psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy in developing societies, particularly in traditional ones. If such a trouble does not resolve wisely, then the progression of psychoanalysis and its modified versions will not succeed smoothly, in spite of its historical and vital position in the realm of psychotherapy and its scientific and logical independence from public morals. Methodical study, training and practice of psychoanalysis, as the highest level of psychodynamic approaches, is the only possible and effective way for supporting and promotion of psychodynamic perspective in conservative developing societies. Ignorance of genuine and pragmatic literatures, based on any kind of reason or motivation, may not have any outcome except than divergence from true pathway and falling behind the contemporary strategy. Bio-psychsocial approach in modern psychiatry cannot be attainable without sensible and clinical considering of ‘unconsciousness’.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest

References

- Fonagy P (2010) Psychotherapy research: do we know what works for whom? Br J Psychiatry 197: 83-85.

- Oakley C, Ryan L, Mc Voy M (2012) Training in psychotherapy: where are we now? in How to Succeed in Psychiatry: A Guide to Training and Practice. In: Wiley-Blackwell (ed), 1st (edn) pp: 50-63.

- Shafti S (2005) Psychoanalysis in Persia. Am J Psychother 59(4): 385- 389.

- Freud S, Breuer J (1893) Studies on Hysteria. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 2-307.

- Freud S (1900) The Interpretation of Dreams. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds.) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp:5-623.

- Freud S (1901) The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 6-291.

- Freud S (1905) Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria. In: Strachey, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 3-122.

- Freud S (1909) Analysis of a phobia in a five-year-old-boy. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 3-149.

- Freud S (1909) Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 153-318.

- Freud S (1911) Psycho-analytic notes on an autobiographical account of a case of paranoia (dementia paranoides). In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, The Hogart Press, London, pp: 3-82.

- Freud S (1911) From the history of an infantile neurosis. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 3-12.

- Freud S (1912) Papers on technique. In: Strachey J, et al. (eds) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogart Press, London, pp: 111-120.

- Shoja Shafti S (2011) Studies on Freudian psychology. In: 3rd (edn), Amir Kabir Press, Iran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2015) Essentials of clinical psychoanalysis. In: 8th (edn), Ghoghnoos Press, Iran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2015) The most important educative papers in the history of psychoanalysis. In: 6th (edn), Ghoghnoos Press, Iran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2015) Application of free association in classical psychoanalysis. In: 8th (edn), Ghoghnoos Press, Iran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2014) An introduction to short term dynamic psychotherapy. In: 1st (edn), Amir Kabir Press, Iran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2019) Psychoanalytic Analysis of Psychopathology. In: 1st (edn), Jami Press, Iran.

- Chisolm MS (2011) Prescribing psychotherapy. Perspect Biol Med 54(2): 168-175.

-

Saeed Shoja Shafti. Avoiding Traditional Psychoanalysis: An insolence Founded on Misconstruction. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 2(2): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000534.

Psychoanalysis; Psychodynamic psychotherapy; Developing societies; Developed societies; Core curriculums

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.