Research Article

Research Article

Alcoholism, Gender, And Mental Illness

Thomas J Bechard* and Peggy Howell Beall**

Public Health & Social Work, Slippery Rock University, USA

Thomas J Bechard, Professor in the Social Work department,

119 Dinger Building, PA, USA.

Peggy Howell Beall, Assistant Professor, Public Health & Social Work, 111 Dinger

Building, PA, USA.

Received Date: February 11, 2019; Published Date: March 19, 2019

Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine gender differences in people with an alcohol use disorder with focus on the cognitive dimension. Social learning theory postulates that the “emotional disturbance” associated with an alcohol use disorder is related to “irrational” thinking [1]. The rational-irrational dimension of cognition was chosen to test for gender differences. This is an ex post facto study, comparing treated men and women with an alcohol use disorder on irrationality and intelligence. An analysis of variance with regression was performed to determine gender-modality effects and gender-modality interaction. It was hypothesized that females would score significantly higher than males on a cognitive functioning scale measuring rationality/irrationality. Results revealed a significant modality effect (P <.01), but neither a significant gender effect (.05 level), nor a significant gender treatment modality interaction effect (.05 level).

There was a relationship between modality and irrationality, but not between gender and irrationality. Irrationality scores were significantly higher (P <.0001) in inpatient modalities than in outpatient modalities. There were no significant differences between gender on the lie or the vocabulary scales. There was a significant inverse relationship between intelligence and irrationality for both genders. The relationship between gender, alcoholism and irrationality in this study is equivocal; i.e., one test showed it, the other did not.

Introduction

Alcohol misuse is linked to approximately 88,000 deaths in the United States annually [2]. It is estimated that 8.4% of adult men (9.8 million) and 4.2% of adult women (5.3 million) have an Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). At least twenty million husbands, wives and dependent children are directly affected by the alcoholic members of their families [3].

The third most frequent offense for which people are arrested is “driving under the influence of alcohol” [4]. According to the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, Inc. [5], 40% of violent crimes are linked with AUD, 37% of people currently incarcerated report drinking at the time they were arrested, and 66% of victims who were attacked by someone known to them reported that alcohol was involved in the incident.

The impact of alcoholism on the health care system and social agencies is no less severe. Problem drinkers account for onethird of the male admissions to both state mental hospitals and the psychiatric units of general hospitals and over one-half of the male admissions age forty-five to sixty-four are diagnosed with alcoholism [6]. A considerable proportion of patients admitted to general hospitals have serious drinking problems. In a study of one-hundred consecutive male admissions to a general hospital, over one-quarter of the patients were classified as addicted to alcohol and another nine percent had serious drinking problems [7]. Udo T, et al. [8] reported a significantly higher likelihood for men with a history of alcohol use disorder to be diagnosed with all medical conditions compared to women with a history of alcohol use disorders, but the number of chronic medical conditions did not differ by gender. This study also reported higher mortality in treatment-seeking men with AUD than women, but reported that women with a history of AUD seem to have an elevated risk for myocardial infarction and liver disease.

In the United States and around the world, men drink more alcohol than women Wilsnack RW, et al. [9], but evidence suggests that the gap is narrowing [10]. Smith PH et al. [11] found that women ending a relationship with a problem drinker were likely to decrease their consumption of alcohol. That study also reported that women separating from a partner who was not a problem drinker, were at risk for increasing their alcohol consumption. Smith PH et al. [11] called for more research to understand the complex factors related to women’s consumption of alcohol at stressful life transitions.

Squaglia LM, et al. [12] analyzed the responses of women alcoholics to a drinking-history and symptoms questionnaire and compared the responses with the Jellinek EM [13], alcoholism symptomatology and phaseology derived from men’s responses. The results illustrated statistically significant differences (p 1<.01) between the women’s and men’s symptoms in the early stages: women reported personality change when drinking, drinking before facing a new situation, and feeling more intelligent and capable when drinking; men reported flashes of aggressiveness and grandiosity, sneaking and gulping drinks. Holdsworth C et al. [14] found differences between older men and women. Men not in a partnership drank more than others, but women who lost a partner drank less. Lipsky S, et al. [15] found that intimate personal violence predicted alcohol misuse among white and black women and white men but not black men. Welty LJ, et al. [16] in a 12-year study found a drop in substance use disorders in females compared to males after detention. This difference may be related to females being more likely to have received services [17].

When studies investigated differences between genders in treated clusters, some evidence suggested that women may not prefer mixed-gendered groups that are common in AUD treatment [18,19]. Greenfield Sf, et al. [20] postulated that women benefit more from all-female groups because of differences in interactional styles between women and men.

Other findings suggest that the differences between women and men are related to affective and behavioral dimensions. Women who are diagnosed with alcoholism were said to be more “abnormal,” more “disturbed,” suffer more “affective disorders” and “personality disturbances” than men with the same diagnosis [21- 23]. Harrington M, et al. [24] reviewed the literature for women diagnosed with alcoholism since 1950. Harrington concluded that both men and women diagnosed with alcoholism had experienced a high incidence of disruptive emotional behavior and deprivation as children, but women experienced more negative events. Other researchers note that there are greater degrees of inappropriate feelings and dysfunctional behavior in women who are diagnosed with alcoholism as compared to men with the same diagnosis [25]. Studies suggest that there are gender differences in this population on affective and behavioral dimensions. It is logical to question whether these differences emerge at the cognitive level related to types of psychopathology.

The task of this study is to examine gender differences in people with an alcohol use disorder focusing on the cognitive dimension. Social learning theory postulates that the “emotional disturbance” associated with the behavioral symptom of alcoholism is related to “irrational” thinking about oneself, others, and/or the world [1]. One aspect of cognition, the rational-irrational dimension, has been chosen to determine gender differences. The criteria for rational thinking have been described by Levinson [26]. Rational thinking refers to: (1) thinking which is based on objective reality, or reality which can be checked by or demonstrated to a disinterested person who has the capacity to check or perceive objectively, the demonstration; (2) thinking which is most likely to preserve one’s life; (3) thinking which enables one to achieve most quickly immediate and long-range goals without (4) significant personal emotional conflict; and (5) without significant environmental conflict.

Irrational thinking refers to thinking which has the opposite characteristics. More specifically, irrational thinking has the following aspects:

(1) The individual believes, often devoutly, that the irrational thinking accords with the tenets of reality, although in some important respect it does not.

(2) People who adhere to irrational thinking significantly denigrate or refuse to accept themselves.

(3) Irrational thinking interferes with getting along satisfactorily with members of one’s primary social groups.

(4) It seriously blocks the achievement of the kind of interpersonal relations that one would like to achieve.

(5) It hinders working gainfully and, or fully, at some kind of productive labor.

(6) It interferes with one’s own best interests in other important respects.

The research posits that women experience inappropriate feelings and more dysfunctional behavior than men. The major hypothesis of this study is that women in treatment for an alcohol use disorder will experience more cognitive dysfunction and will score significantly higher on an irrationality scale than men. Irrationality as defined by the cognitive-learning perspective, is the extent to which an individual manifests irrational ideas as measured by a rationality-irrationality scale.

Two variables, vocabulary score (highly correlated with I.Q.) and “lie” tendency have significance in relation to the rationality-irrationality dimension. With respect to vocabulary scores, it was anticipated that the higher the irrationality, the lower the intelligence. The “lie” questionnaire was included as a methodological check based on the tendency not to answer questions truthfully; i.e., to determine whether gender differences in irrationality were real or of the order of artifacts.

Method

All subjects signed The Informed Consent Form. This form (see Appendix A) is explicit that participation in the study was voluntary. Participants were drawn from five treatment facilities- -two outpatient (the Alcoholism Clinic [NCMC-01; Employee Counseling Service INCMCE-01) and three in patient (Recovery House [RH-I]; Plainview Rehabilitation Center [PRC-I]; the Detoxification Unit [NGMCD-I]). These services were administered by the Nassau County Department of Drug and Alcohol Addiction, Nassau County, Long Island, New York.

Design

This study was designed as ex post facto research, comparing treated men and women with an alcohol use disorder on two attributes: irrationality and intelligence. Five samples included males and females receiving counseling for an alcohol use disorder at five treatment facilities--two outpatient, three inpatient units, Plainview Rehabilitation Center, and the Detoxification Unit. Not all individuals who have such an alcohol use disorder seek help, therefore, the samples can be thought of only as representative of those who are forced by circumstances (arrest, probation, and so forth) or who voluntarily seek assistance.

Participation

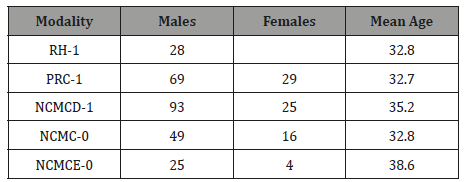

Through the procedure of non-random accidental sampling, subjects who were at hand were recruited until the time period for data collection had terminated. The subjects consisted of 338 individuals: 264 men in treatment for alcoholism, and 74 women in treatment for alcoholism. A frequency distribution of gender and mean age within each modality is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Frequency distribution for modality, gender and mean age.

Variables

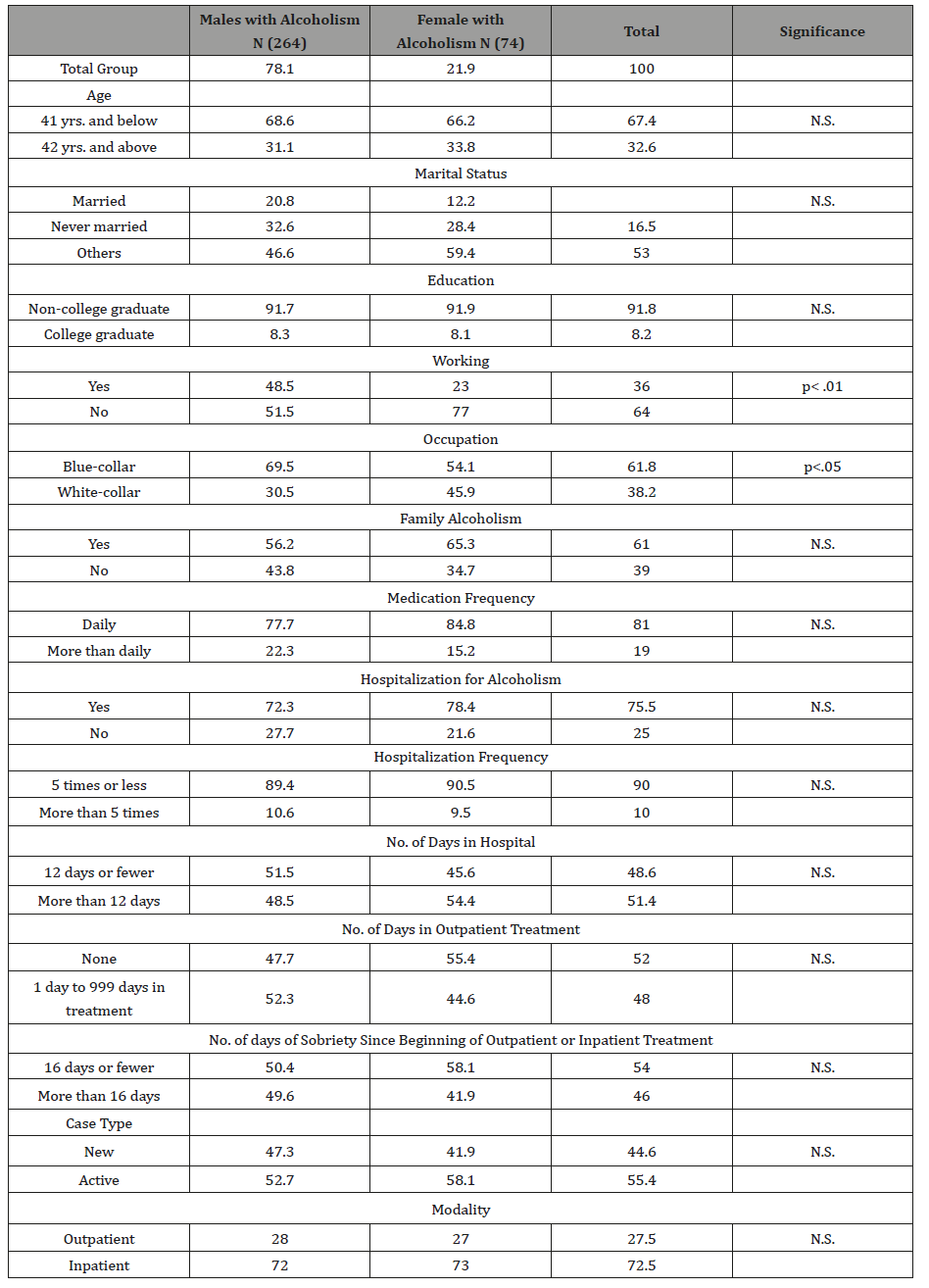

Variables were subjected to a percentage distribution calculation. This procedure yielded variables that are presented in tabular form in Table 2. Of the 21 variables, five variables (work, occupation, suicide attempt, drinking pattern, and drinking problem) emerged with gender differentiation beyond the .05 level of significance.

Table 2: Summary, percentage distribution of the sample according to gender.

1. Men treated for an alcohol use disorder worked more often than women.

2. Men worked more often in blue-collar occupations than; women worked more often in white-collar occupations.

3. Women in treatment reported making suicide attempts more often than men.

4. Men in treatment for alcoholism reported drinking with others more than women; women in treatment for alcoholism reported drinking alone more often than men.

5. Women had a drinking problem for the past four years more often than men; in a 4-10 year period women consistently reported a drinking problem more often than men; and men reported a drinking problem for 10-15 years more often than women. The sample, therefore, was homogenous in relation to 16 of the 21 variables on the gender criterion, but was significantly heterogeneous within five of the 21 variables.

Instruments

The Adult Irrational Ideas (A-I-I) Inventory was constructed by Davies RL, et al. [27]. The response mode of the A-I-I Inventory is the conventional five-point Likert (1932) scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The most rational score is 60; the most irrational, 300. Thus, higher scores indicate a higher degree of “irrationality.”

The Kuder-Richardson formula 20, the KR-20, was calculated on both the pretest and posttest yielding a reliability estimate ranging from .743 to .779. Construct validity was also established by comparing the A-I-I results obtained from three criterion groups: 82 mental hospital patients, 57 alcoholics, and 113 individuals drawn from the general population of Edmonton, Canada.

The Lie Scale is one of the three validating scales: L (lie), F (validity), and K (correction) of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) [28]. It is made up of 15 items which had previously been tested in research on deceit by [29]. A high score on this particular scale reflects a tendency to put oneself in a favorable light. The Lie Scale was included in the testing protocol for this research study to control for dishonesty.

The Vocabulary Scale (see Appendix B) was constructed by Shipley (1940) to provide a quick, objective, self-administering measure of mental deterioration. Reliability coefficients obtained were 0.87 for the vocabulary test, .89 for the abstract-thinking test, and 0.92 for the two combined. The last of these coefficients virtually represents the reliability of the vocabulary scale when used as a measure of intelligence. The vocabulary test was the part of the scale that was used as the last test in the protocol for this research study.

Procedure

Each subject in this study was given five self-administered questionnaires in booklet: An Informed Consent Form (ICF), an Identifying Data Questionnaire (IDQ), the Adult Irrational Ideas Inventory (AIII), the Lie Scale (LS), and the Vocabulary Scale of the Shipley-Hartford Scale for Measuring Intellectual Impairment, and Deterioration (VC). All five questionnaires (ICF, IDQ, AIII, LS and VC) were bound together in a single booklet (protocol) and administered to the subjects in one sitting. All the subjects in each treatment unit were tested, the males along with the females--with the exception of the few (21 or 6% of the total) who decided not to participate because of illiteracy or fatigue. Most of this attrition rate occurred in the Detoxification Unit (NCMCD-I) which had an attrition rate of somewhat less than 18%.

Treatment modality is one of the major control variables; i.e., subjects may be distinguished on the basis of the populations from which they are drawn. The subjects who come from different modalities are not distributed equally; i.e., there are fewer females than males within each modality. The difference in the distribution of males and females across modalities was variable. The range varies from 6:1 to 2.3:1 as compared to an average ratio of 5:1 for the general population with alcoholism.

Results

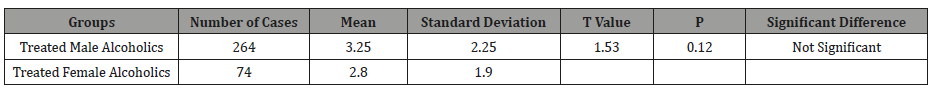

When the “lie” scores of males and females were compared (Table 3), they did not differ significantly (t = 1.53; p = 0.12). Men with alcoholism answered more “Lie” items than women with alcoholism with mean scores of 3.25 and 2.80 “lies” respectively.

Table 3: “Lie” scores for males and females.

Based upon the literature it was hypothesized that women clients with alcoholism would score significantly higher on an irrationality scale than their male counterparts. When mean A-I-I scores are compared with regard to modality and gender, in three out of the four treatment modalities women clients with an alcohol use disorder had higher irrationality scores than their male counterparts.

As a preliminary analysis of the gender effect t tests were performed on A-I-I scores between males and females. The tests were performed on the gender effect separately for each modality. The t values and the degrees of freedom for modalities PRC-I, NCMCD-I, NCMC-0, and NCMCE-0 were respectively: 1.17 (96), 1.46 (116), 1.47 (63), and -.36 (27). None of these tests indicated a significant difference. However, a test of the combined t values from all the treatment modalities (z test based upon individual t values) indicated that the combined t score differed significantly from 0 (z = 1.84; p = .033). This analysis indicated a significant gender effect; i.e., a relationship exists between gender and irrationality; i.e., females had higher irrationality scores than males.

An analysis of variance with regression was performed to determine the gender and modality effects as well as gender and modality interaction. The results revealed a significant modality effect (4.01) but neither a significant gender effect (.05 level) nor a significant gender treatment modality interaction effect (.05 level). There was a relationship between modality and irrationality, but not between gender and irrationality.

There is a discrepancy between the analysis with regression and the “combined t.” The overall conclusion is that whether either statistical procedure is accepted at face value, if there is a gender effect, it is very weak. The major hypothesis is thus rejected.

A modality effect was found. A difference in irrationality between the inpatient and out-patient groups was found. This apparent difference was investigated by a t test procedure and was found to be significant beyond the .01 level.

The concept that irrationality scores are significantly higher in inpatient modalities than in outpatient modalities is refuted in one instance by the mean irrationality score of 172.57 obtained in the RH-I group. This score bears almost exact resemblance to the outpatient mean scores. In all categories in which the two groups were sampled, the mean irrationality scores were higher, but not significantly different for the females than the males with the exception of the NCMCE-0 group in which the reverse was true. These differences may be the result of sampling error instead of a gender effect. If a gender effect is present, it may not be detected because there are not enough observations to discover a significant interaction.

Vocabulary scores of males and females were compared. They were found not to differ in the expected direction (.05 level; t = 0.32; p = 0.74). When males and females were compared on the vocabulary scale, no significant differences were found.

Discussion

The relationship between gender, alcoholism and irrationality in this study is equivocal. Gender differences regarding irrationality within each modality were not significant. The combined t-test of all of the modalities yielded a significant difference between men and women on irrationality scores. Gender might be studied more effectively by using larger samples. In terms of control variables, two variables--treatment modality and vocabulary scores--have been shown to correlate with irrationality in this study. Future studies would be expected to utilize larger samples and single modalities in which treatment modality and vocabulary scores are controlled for the purpose of sample homogeneity.

These findings suggest that further research regarding gender differences and alcohol use disorders may be informative regarding the presence and character of differences between men and women. Social learning theory as applied to alcoholism has definite implications for social work research, especially the efforts to investigate the etiology of the disease. The theory maintains that a client with alcohol problems can be understood in terms of her/his thoughts and emotions and in terms of manifest behavior.

The findings reveal an association between the treatment modality and irrationality; i.e., people were systematically different in irrationality from one modality to another. This implies that the modality effect may be a reflection of degree of pathology; inpatients, presumably with more pathology, showed higher irrationality than outpatients.

The results of this study showed no significant gender differences in intelligence between men and women with an alcohol use disorder. Grant BF, et al. [30] found increases in alcohol use, high risk drinking, and increased alcohol use disorder among women. It is critical to the wellbeing of women that research into the differences between the etiology of alcohol use disorders and differences in treatment effectiveness for women and men proceed vigorously.

The results did uncover a significant inverse relationship between intelligence and irrationality that is applicable to both genders; i.e., the higher the irrationality, the lower the intelligence. There is, however, limited evidence that favors the investigation of factors related to the modality effect and irrationality. These factors include the etiopathogenesis of alcoholism and its relationship to the social learning theory process (precipitants from the psychosocial history related to cognitive, emotive and behavioral processes in a circular fashion).

These variables are relevant to intervention content in the social work curriculum; i.e., the knowledge base for intervention could focus on the circular relationship between these variables and, consequently, their implications for social work intervention in the psycho-social matrix. Finally, the results of the study suggest significant differences between the general population and people with an alcohol use disorder regarding the rationalityirrationality dimension. This finding suggests further investigation of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for people who have alcohol use disorders. Cognitive Behavior Therapy is established as an evidence based practice. The American Psychiatric Association published new practice guidelines in 2018 for the treatment of alcohol use disorders and identifies cognitive behavior therapy as a recommended psychotherapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mar RA (2011) The neural bases of social cognition and story comprehension. Annu Rev Psychol 62: 103-134.

- (2016) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, USA, pp. 1-413.

- Lee JD (2011) Substance use prevalence and screening instrument comparisons in urban primary care. Subst Abus 32 (3): 128-134.

- (2015) National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD).

- Finklea KM (2009) Organized crime in the United States: Trends and issues for Congress. Journal of Current Issues in Crime, Law & Law Enforcement 2 (1): 9-40.

- Laslett AM, Room R, Dietze P, Ferris J (2012) Alcohol’s involvement in recurrent child abuse and neglect cases. Addiction 107(10): 1786-1793.

- Heather N, Adamson SJ, Raistrick D, Slegg GP (2010) Initial preference for drinking goal in the treatment of alcohol problems: I. Baseline differences between abstinence and non-abstinence groups. Alcohol Alcohol 45(2): 128-135.

- Udo T, Vásquez E, Shaw BA (2015) A lifetime history of alcohol use disorder increases risk for chronic medical conditions after stable remission. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 157: 68–74.

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz Holm ND, Gmel G (2009) Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction 104(9): 1487-1500.

- White A, Castle IJP, Chen CM, Shirley M, Roach D, et al. (2015) Converging Patterns of Alcohol Use and Related Outcomes Among Females and Males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39(9): 1712–1726.

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR (2012) Women ending marriage to a problem drinking partner decrease their own risk for problem drinking. Addiction 107(8): 1453-1461.

- Squeglia LM, Sorg SF, Schweinsburg AD, Wetherill RR, Pulido C, et al. (2012) Binge drinking differentially affects adolescent male and female brain morphometry. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 220 (3): 529-539.

- Jellinek EM (1952) Phases of alcohol addiction. Quarterly Journal of Studies in Alcoholism 13: 673-684.

- Holdsworth C, Frisher M, Mendonça M, DE Oliveiria C, Pikhart H, et al. (2017) Lifecourse transitions, gender and drinking in later life. Ageing Soc 37(3): 462-494.

- Lipsky S, Kernic MA, Qiu Q, Wright C, Hasin DS (2014) A two-way street for alcohol use and partner violence: Who’s driving it?. Journal of Family Violence 29(8): 815-828.

- Welty LJ, Harrison AJ, Abram KM, Olson ND, Aaby DA, et al. (2016) Health disparities in drug- and alcohol-use disorders: A 12-year longitudinal study of youths after detention. Am J Public Health 106(5): 872-880.

- Teplin L A, Abram KM, Mc Clelland GM, Washburn JJ, Pikus AK (2005) Detecting Mental Disorder in Juvenile Detainees: Who Receives Services. Am J Public Health 95(10): 1773–1780.

- Cucciare MA, Simpson T, Hoggatt KJ, Gifford E, Timko C (2013) Substance use among women veterans: Epidemiology to evidence-based treatment. J Addict Dis 32(2): 119–139.

- Lewis ET, Jamison AL, Ghaus S, Durazo EM, Frayne SM, et al. (2016) Receptivity to alcohol-related care among U.S. women veterans with alcohol misuse. Journal of Addict Dis 35(4): 226–237.

- Greenfield SF, Pirard S (2009) Gender-specific treatment for women with substance use disorders. In KT Brady, SE Back, SF Greenfield (Eds.), Women and addiction: A comprehensive handbook. The Guilford Press, New York, USA, pp. 289-306.

- Herschl L (2012) Implicit & explicit alcohol-related motivations among college-binge drinking. Psychopharmacology 221(4): 685-693.

- Weichelt SA (2012) Historical trauma among urban American Indians: Impact on substance abuse and family cohesion. Journal of Loss and Trauma 17 (4): 319-336.

- Hubachek JA (2012) Fat mass and obesity-associated to gene and alcohol intake. Addiction 107(6): 1185-1186.

- Harrington M, Baird J, Lee C, Nirenberg T, Longabaugh R, et al. (2012) Identifying subtypes of dual alcohol and marijuana Users: A methodological approach using cluster analysis. Addict Behav 37(1): 119-123.

- Steingrimsson S, Carlsen HK, Sigfusson S, Magnusson A (2012) The changing gender gap in substance use disorder: A total populationbased study of psychiatric in-patients. Addiction 107(11): 1957-1962.

- Levinson MH (2010) Alfred Korzybski and rational emotive behavior therapy. A Review of General Semantics 67 (1): 55-63.

- Davies RL, Zingle HW (1970) Adult Irrational Ideas Inventory (Adult I-I Inventory), University of Alberta, Canada.

- Hathaway SR, Mc Kinley JC (1942) A multiphasic personality schedule. The measurement of symptomatic depression. The Journal of Psychology 14: 73-84.

- Hartshorne H, May MA (1928) The statistical approach to the study of character. In studies in the nature of character, [part] 1: studies in deceit: book 1, general methods and results; book 2, statistical methods and results (3-11).

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, et al (2017) Prevalence of 12-Month Alcohol Use, High-Risk Drinking, and DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 74(9): 911-923.

-

Thomas J Bechard, Peggy Howell Beall. Alcoholism, Gender, And Mental Illness. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 1(5): 2019. OAJAP. MS.ID.000523.

Cognitive, Alcoholism, Alcohol Use Disorder, Drug Dependence, Drinkers, Psychiatric units, Alcoholics, Drinking-history, Autism, Spectrum, Disorder, Social environments, Health Service, Social Services, Intoxicant, Optimism, Physiological ecology, Addiction, Rehabilitation, Behaviour, Optimistic, Neurological, Mental health, Cognitive, Mental capacity

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.