Research Article

Research Article

Alcohol Use Disorder Recovery in Ethiopia

JAmanuel Haile Asfaw1* and Jane Warren2

1Department of Psychological Science and Counselling, USA

2Department of Counselling, USA

Amanuel Haile Asfaw, Department of Psychological Science and Counselling, USA.

Received Date: August 01, 2019 Published Date: August 26, 2019

Abstract

This hermeneutic phenomenological study explored the lived experiences of six people in Ethiopia who succeeded in recovery from alcohol use disorder. Their stories enhance our understanding of longterm recovery. Implications for counselor education and suggestions for further research are discussed.

Keywords:Alcohol use disorder; Long-term recovery; Hermeneutic phenomenology

Introduction

Alcohol overuse and abuse is a global challenge; not just a problem in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration SAMHSA [1]. This study attempted to understand the lived experiences of six Ethiopian recovering persons recovering from alcohol use disorder and to offer a multicultural view of recovery. The country of Ethiopia has problems with substance use and overuse. Alcohol and khat leaves (Catha edulis) are widely abused substances that cause people to seek psychiatric treatments [2-6]. CSA & ICF International [12] reported the prevalence of alcohol use in 53% of men and 45% of women in Ethiopia. Additionally, the WHO [8] revealed that 9.3 percent of Ethiopians practice heavy and hazardous drinking. In many developing countries like Ethiopia, there are alcohol overuse patterns. Patel V [10] described developing countries’ drinking patterns as hazardous, heavily gendered towards men, high-risk and often manifested through drinking alone and binging. Access to use is a cultural phenomenon in Ethiopia given that drinking on holidays and during festivals is socially acceptable; people can easily get homebrewed drinks or buy from liquor stores mostly without age restrictions. Across all cultures overuse of alcohol and other drugs is often associated with physical, mental, economic, and social negative consequences [11-14]. In some studies, substance overuse is associated with crime, anti-social behaviors, unemployment, lost occupational productivity, HIV/AIDS, early childhood traumas, and personal and family problems [15-21]. There is considerable research on how recovery from substance overuse and abuse is achieved. For instance, research results reveal Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) to be an effective treatment for a wide range of overuse of substances [22-25]. Strategies as prayer in AA have been found correlated with reductions in cravings [26]. Other research findings suggest the effectiveness of various individual and group interventions such as Motivational Interviewing (MI), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (Dutra et al, 2008), mindfulness-based interventions Witkiewitz K, et al. [27], and family-based substance abuse treatment [28]. In addition, research supports numerous factors that support recovery such as cultural background Pruett JM, et al [29], spiritual perspectives Warren J [30], and exposure to people with substance abuse disorders [31].

Previous studies in the western culture focused on evidenced based short-term treatments, medications, and self-help groups to identify what works to help a person initiate and sustain shortterm recovery however, a short-term focus leaves a gap in knowing what maintains long-term alcohol recovery [26,32]. In addition, questions remain on how does a person recover from alcohol use disorder in a setting where there is low access to treatment, poor health care, lack of support group, and substantial poverty? If success in abstaining from alcohol use does happen when there is not treatment, medications or support groups easily available, what can we learn? Through hermeneutic phenomenology, this study focused on understanding how six Ethiopian men stayed in recovery from alcohol use disorder for at least 10 years. Diverse aspects of their challenges and successes such as stigmas, coping mechanisms, feelings, and support systems were explored. Research that studies the lived experiences of people in long-term recovery from alcohol use disorder is lacking [25]. Although El-Guebaly N [33] completed a 10-year review of recovery literature and found numerous definitions, an agreement on a single definition of recovery was not found [34]. For this study, recovery was defined as a personal condition of abstaining from alcohol and not as a specific treatment approach outcome [35]. Since extended abstinence is predictive of sustained recovery NIDA [14], the abstinence model of recovery (not using any alcohol) was used in this research.

Method

Following obtaining permission from the university’s Institutional Board Review (IRB), this study was conducted from June 2014 through April 2015. The interviews were all done in person and in Ethiopia by the primary researcher (the first author), who himself grew up in Ethiopia and defines himself as Ethiopian. He was able to speak the native language of the participants.

Participants

Through word of mouth and radio, six residents of Ethiopia were selected. They were all screened for an alcohol use disorder using the DSM-5 APA [36] and reported having a minimum of 10 years of clean time from alcohol and drugs. None of the participants had attended treatment before and they all reported they were recovering on their own. The participants were all male, ranging in age from 30 to 73 years, with their years in addiction ranging from 2-20 years, and their years in recovery varied from 11 to 27 years. In order to ensure confidentiality, participants were given pseudonyms. This study was limited to recovery from alcohol use disorder, excluding recovery from other drugs.

Research Methodology

Procedures

A written informed consent was provided to the participants before the start of any data collection process. The informed consent (e.g. the purpose of the study, the benefits and risks of participating in the study, the timeline of the study, and the use of pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality) was discussed with each participant and the primary researcher answered participants’ questions about the research process. The data collection was done in a private and confidential place that each participant chose in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. In order to understand the lived experiences of people in long-term recovery from an alcohol use disorder, the primary researcher conducted two unstructured phenomenological interviews, each lasting 60-90 minutes, with each participant. The interviews began with open-ended prompts and additional follow-up questions were asked. In addition to two lived experience interviews and an additional telephone check in lasting 45-60 minutes to inform participants with emerging themes, the researcher was also the primary source of data collection in this qualitative study [37]. The data were audio-recorded, translated, and transcribed.

Data analysis

A qualitative approach was used because it allowed participants to construct their own meanings about their experiences. Green J and Thorogood N [38], Liamputtong P [39] stated that qualitative research examines subjective human experiences and the interpretations people have about their lives and world. Rooted on the philosophy of Edmund Husserl, descriptive phenomenology aims at “depict[ing] the essence or basic structure of experience” by bracketing previous beliefs about the phenomena [37]. Although a pure phenomenological research claims to describe a phenomenon free from biases and prejudices Silverman HJ [40], there are always biases in researchers and writers [41-43]. This study employed a hermeneutic phenomenological approach combining features of description and interpretation Cohen MZ, et al. [44] while seeking to attain a deeper understanding and meaning of the lived experiences Kafle NP [45] of people in long-term recovery from alcohol use disorder in Ethiopia. During this analysis work, the primary researcher moved back and forth between the parts of the lived experience descriptions and the overall recovery narratives. From this interchange, an understanding emerged [46]. This process involved several tasks such as underlining and coloring chunks with similar meanings, grouping similar segments, giving name to the chunks/groups, exploring the relationships between and among themes, and conceptualizing the participants’ lived experiences by linking it with literature [47]. Structural analysis helped to uncover substantial issues about how narratives are told that could otherwise be easily overlooked in thematic analysis [48]. This analysis assisted in understanding participants’ lived experiences by considering how their stories were structured and presented in their cultural and textual contexts.

Trustworthiness

To ensure trustworthiness and address the researcher biases, numerous strategies were used including member checking, peer review by the secondary author, reflective journal, adequate engagement in the data collection, and triangulation [49]. Member checking seeks to gain feedback from the participants on the emerging findings of the study [39]. The member checking process offered the primary researcher a second chance to validate the findings by engaging in further conversations with the participants. Peer debriefing which involves “asking a colleague to scan some of the raw data and assess whether the findings are plausible based on the data” was employed in this research [37]. This type of review offered feedback on the initial findings and the relationships between the codes, themes, and emerging findings [39]. The primary peer reviewer in this study was the secondary author, who scanned the anonymous participants’ data and offered insights throughout the study.

Use of a reflective journal refers to “critical self-reflection by the researcher regarding assumptions, world views, biases, and theoretical orientations, and relationships to the study that may affect the investigation” [37]. Reflecting on personal assumptions regarding the phenomena being studied will help illustrate how the researcher arrived at a meaning or understanding [37]. The first author identified assumptions related to addictions and recovery that may influence not only the data collection process, but the analysis and result presentation and reflected on them throughout this study. In addition, the first author also documented his ideas, feelings, experiences, and initial reactions during interviews and the interpretation work in order to decrease subjective interpretations and gain good understanding of participants’ perspectives of their lived experiences. The information from the reflective journal was mindfully infused throughout the analysis process. Two additional means were employed in this study to increase trustworthiness. One was triangulation, which is “using multiple investigators, sources of data, or data collection methods to confirm emerging themes” and the second was adequate engagement in data collection, which suggests “adequate time [be] spent collecting data such that the data becomes saturated” [37]. The first author met with participants twice to collect thick data regarding their lived experience descriptions and contacted the participants to obtain their feedback and input on the emerging findings as part of the member check process.

Findings

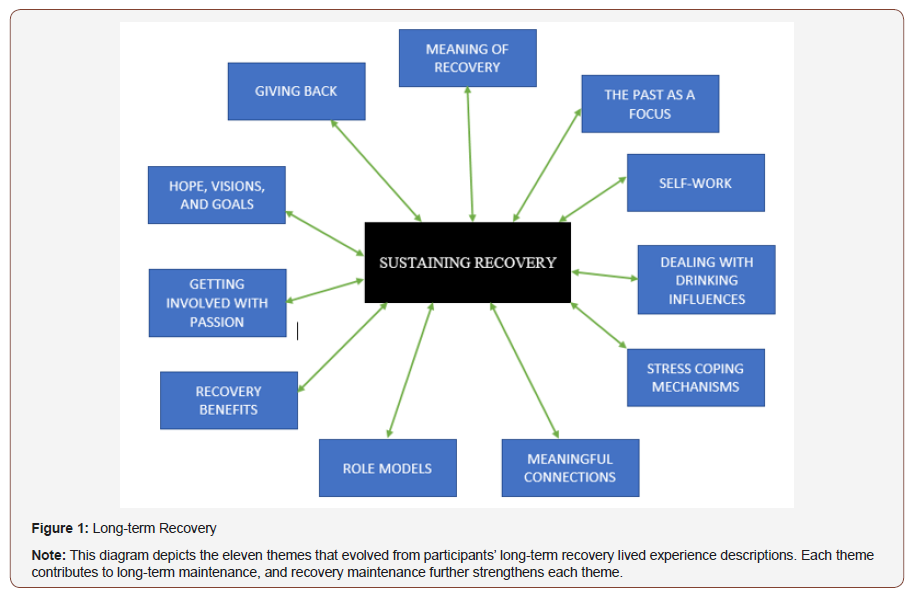

The finding revealed that long-term recovery was complex and included eleven themes (Figure 1).

Meaning of recovery: Participants reported that recovery is more than abstaining from alcohol. They all offered special meanings and definitions of their recovery experience. For instance, one participant mentioned that taking a drink meant: losing the “battle” he had been fighting since quitting alcohol, and for others quitting recovery meant losing “childhood wishes,” “self-confidence and self-worth,” and giving up their “hopes, dreams, goals, and visions.” Another participant reflected that recovery meant “connection” with himself and experiencing “real feelings,” which he was unable to experience during his pre-recovery times, while another stated that recovery is “re-birth and re-living” and reusing alcohol would mean going back to the “dark time” [period of addiction]. Although participants had different meanings and values for recovery, they all described that taking a drink does not equal a drink; it equals “addictions,” “struggles and destructions,” “losing family and higher power connections,” and losing one’s “peace of mind.”

The Past as a Focus: The focus on the past was present in almost every aspect of the participants’ descriptions. One participant described: In the past, I would get headaches, experience sleep problems, and get grumpy and aggressive to others. I was not able to manage and save money properly, and I had a lot of struggles. Furthermore, I did not have good interaction with my family and would feel stressed about life in general. Now, things are different… my sleeping pattern has changed a lot. I go to bed early and wake up early...and have a peaceful day. I read the Holy Bible before I go to bed and this keeps me away from being slaves to evil spirit. It is kind of problem free life.

All the participants had previous negative consequences from their alcohol use disorder. As a child, one participant reported he chugged the “Areke [homebrewed alcohol]” made by his sister, however he passed out for a long time, experiencing the negatives of alcohol use early in his life. He commented on the negative consequences of his problem drinking as, “Looking back what I did, I now ask myself “was I a human being or an animal? .... I came to learn that I was infected with HIV/AIDS…” In addition to experiencing the multi-faceted negative consequences from alcohol use, most of the participants reported times in the past when they experienced embarrassing moments. As one participant shared, “When I woke up at 3 am in the morning, I was sleeping outside my house. I was shocked and regretted my decision to drink alcohol.” Other issues which participants experienced in the past include suicide, financial stressors, and judgment from others.

Alcohol overuse was viewed as a trap: Your brain would make a final decision [not to drink alcohol] and [you]would blame yourself for what happened [for drinking again regardless of your decision not to drink … I blamed myself too much and contemplated and prepared to kill myself with the pistol I owned [ showing a picture of it]. I had planned to shoot a beer bottle [first] to show [others] that it’s alcohol that ruined my life and kill myself afterwards. To get out of this trap of alcohol use disorder, all of the participants had to do considerable work on themselves.

Self-Work: Engaging in self-work was an important part of all participants’ recovery journey. One participant’s self-work was to continue using every opportunity possible to honor the decision he made to quit his alcohol use. He reported pride about his decision to quit alcohol and stressed that due to his recovery, he is currently living in “Heaven” and able to avoid being hurt in “Hell.” “If I had continued drinking alcohol, I wouldn’t have lived for one year, let alone twenty-seven years.” For another participant, selfwork was focused on being more assertive and committed to his recovery journey. In general, recovery from their alcohol use was the combined effect of participants’ self-work with support for no use from others; however, sometimes the others were influencing participants to reuse alcohol.

Dealing with Drinking Influences: Participants’ recovery journey helped them to develop new ways of dealing with drinking urges such as “assertiveness,” “use of humor,” telling others that they were “told not to drink by doctors,” respecting their own “decision not to drink alcohol,” and “avoiding” those who make fun of them for abstaining from alcohol. One participant said drinking is “always a no for me.” And he added, “people suggest [to me] that doctors recommend drinking some alcohol daily for better health.” However, in summary he responded, “I had more than enough in the past and I should be able to use some of it daily.” Another participant described, “When my new friends asked me to go with them and get some drinks, I turned them down and told them how much I would appreciate if they stopped asking me again.” The participants reported they were better equipped with strategies to deal with drinking influences at parties, ceremonies, and social and cultural gatherings. Although successfully coping with drinking pressures was related to not using, the participants all reported they also used new ways of coping with stress in their lives.

Stress Coping Mechanisms: Many of the participants revealed that they had alternative stress coping mechanisms to cope with non-drinking related stressful events in their lives. One participant commented, “There are valleys and peaks in life, and the first thing I would do when I feel down or sad is prayer.” He continued, “It is prayer that answers everything about life’s mystery.” Another participant added, “When I have stressful issues in life, I would go to a church and pray for me and others. I forgive people and pray for them as well.” Prayer was used as an important coping method to face life struggles after quitting their alcohol use. After carefully exploring the different strategies to support his decision to quit alcohol, three techniques that seemed to resonate with one participant were: “going to a religious center,” “staying away from people who were addicted,” and “practicing staying at home.” To test the strength of these techniques, this participant moved to his brother’s place, “which was 100 kilometers away” from where he used to live. By moving to a new place, he did not only change the places where he would hang out, but found new “friends,” “experiences,” “lifestyle,” and “daily routines.”

Meaningful Connections: The connections the participants established and maintained with themselves, friends, family, and a higher power, were important to their recovery. Before when they overused alcohol, they seemed to be isolated, withdrawn, and disconnected; now they had new connections at churches, homes, and workplaces. One participant met his “good friends at the church” and considered them as his “meaningful group of friends.” For others, their connection was focused on restoring the family relationships. One participant mentioned his goal in his remaining life was to maintain his spiritual connection with God and to continue living in his temple. Almost all the participants mentioned repairing and protecting relationships was their daily priority.

Role Models: The participants reported that they had positive role models such as “Jesus Christ,” and “Mother Theresa,” who impacted their lives positively. One participant switched his prerecovery role model, “Bob Marley,” to a new recovery model, “Jesus Christ.” He mentioned, “The way [Jesus Christ] behaved in this world for 33 years was my model.” He follows the teachings of Jesus Christ and strives to treat himself and others with “love” and “respect.” In addition to changing their own role models, the participants themselves became role models for others. For instance, a participant stated, “Many people would come to me and say, ‘You’re our model,’ and we stopped our alcohol use because of your advice on the TV and radio.”

Recovery Benefits: To help them not use alcohol again, the participants reported multi-faceted benefits of recovery. One participant mentioned how his recovery improved his relationships: “My decision to stop alcohol made my wife proud and we became happy in our life.” His previous “distant” relationship with his children improved greatly after quitting his alcohol use. The various “social,” “financial,” “physical,” “emotional,” “spiritual,” and “occupational” benefits of recovery helped strengthen participants’ commitment and dedication to maintaining their recovery journeys. The participants’ lived experience interviews indicated that the longer they stayed in recovery and the more benefits they discovered, the more they enjoyed talking about their recovery.

Getting Involved with Passion: Participants were now staying busy with passionate endeavors. Some were involved in work and business, while others participated in spirituality, sports, and humanitarian activities. One participant described things he loved doing on a daily basis: I begin my day with Morning Prayer at the church. Then, I read the Holy Bible at home, take a nap for a while, eat lunch, take a walk, and end my day by going to the church and thanking God. Religion is at the center of my life. Although spirituality was an important part participants’ recovery journey, they reported other activities they passionately practice such as “frequent travel,” “sports,” “education,” and “business.” Most participants reported the benefits of workouts; one participant described his involvement in workouts, “my workouts cured my addiction.”

Hopes, Visions, and Goals: All the participants reported that their recovery journey was filled with new hopes, visions, and goals. Although their pre-recovery times were characterized by traps of hopelessness, self-hatred, suicidal thoughts, and addictions, recovery granted them new purposes that they strived to accomplish every single day of their life. For instance, one participant’s new goal was to fight the “evil spirit” that caused his addiction through “prayers, fasting, and the Holy Water.” He woke up every morning with a mission to accomplish- “fighting the evil spirit.” Four other participants found purpose in “helping others.”

Giving Back: Every participant indicated that they engaged in various giving-back activities. Some of them now teach and advise others about the consequences of addiction; while others mentioned that they serve their community through volunteer activities. One participant described, “…I used to run to bars, but now I run to doing humanitarian charity work.” He added, “I do volunteer work for a local NGO [in Ethiopia] …. I meet higher officials …to advocate for others.” In addition to serving others, their involvement in giving back work assisted them to build new names in their society and reclaim social acceptance and respect.

Discussion

Results from this study validate that the recovery experience is a complex and multilayered process. This complexity means that no single factor is adequate to capture the lived experiences of people in long-term recovery from alcohol use disorder. In this study, there were eleven themes that described participants’ lived experiences of initiating and sustaining their long-term recovery. These findings are consistent with a view that no single pathway works for everyone [34, 42]. This study’s results show that people who are in long-term alcohol use disorder recovery view their successes in unique ways; they have different meanings and values associated with their recovery. For the participants, recovery was more than abstaining from a drink; it was a process of “repenting” and a way to get closer to God and remain connected with him. People in alcohol recovery differ on how they understand and value recovery the same way addiction professionals differ on their conceptualization and definition of recovery [33, 35, 42, 50, 51].

Sustaining long-term recovery learns from the past and focuses on the future and is a continuous process [34] requiring people to engage in an ongoing self-work. The participants’ lived experience descriptions indicated that recovery is less about blaming oneself for past mistakes and destructions and more about building on the current accomplishments, self- efficacy, assertiveness, and commitment. It became evident from this study that people in long-term recovery from alcohol use disorder have different selfwork issues at different stages of recovery. The lived experience descriptions indicated that they used adaptive stress coping mechanisms when faced with daily life challenges and drinking pressures. Initially in their addictions journey, participants relied heavily on excessive alcohol use to deal with negative events in life which is similar to findings from studies about alcohol overuse. Alternative stress coping mechanisms such as prayer, forgiveness, walking, swimming, and workouts were critical to not reusing alcohol. These results support that there are many ways people stay recovered [24, 26, 29-31].

The findings revealed that alcohol recovery required the ability to deal with drinking pressures at social and cultural gatherings. In dealing with drinking pressures during holidays and social gatherings, the participants reported using a variety of techniques such as being more assertive, avoiding pressuring friends, respecting one’s decision and increasing commitment, using a sense of humor, and focusing on fun activities such as dancing and singing. Establishing and maintaining connection was deemed helpful by participants as they were sustaining their recovery journey. Restoring broken relationships with their families and/or establishing new connections at church, work, or place of residence were important to the recovery. The participants reported establishing new relationships or restoring their old relationships that alcohol destroyed in the past. Although the participants in this study may not have had the opportunity to establish a therapeutic relationship with a counselor, research suggests that a therapeutic relationship is an important reason connected to how people change [1,22,50,54]. The new or restored connections participants established were considered their primary support systems and facilitated recovery journeys. This is consistent with Brewer MK [55] finding that developing support system fosters the recovery process. Relationships were important to recovery; in addition, ways to cope with life was also important.

A big part of succeeding with long-term recovery from alcohol use disorder was getting involved in passionate activities and giving back. Participants reported with great pride and sense of accomplishment how their active giving back involvement in school, work, business, or spiritual activities was related to their recovery. Be it school, business, church, or volunteer work, they all reported something that interested them. In addition to keeping themselves busy with their passionate activities, the participants mentioned their continuous involvement in humanitarian services. Compared to their hopeless and purposeless life experiences most of the participants had when they were practicing problem alcohol use, their recovery lives were filled with new hopes and goals. It was evident from the lived experiences that the goals and visions the participants had chosen were granting them things such as respect, privilege, dignity, health, and happiness, which alcohol took away from them. Sharing recovery success stories with the public and using it to educate others helps both the recovering person and the society [55]. Through their involvement in giving back activities, the participants successfully reclaimed the self Laudet AB [54], social acceptance, and regained their good name that problem alcohol use stole from them. In fact, some of the participants have been considered as recovering role models by their society. Consistent with SAMHSA [1] recommendation for sustaining recovery, the participants stay connected with their community through their giving back and sharing activities. Moving from being labeled as the “drunk and useless” to becoming a “role model” gives participants a sense of “respect,” “love,” and “value.” From switching models, to becoming role models to others, the participants appreciate the benefits that recovery granted them. Research has shown that people in natural recovery, without formal treatment access, have good social support, better stress coping mechanisms, and engage in positive self-talk, self-work, and introspection without receiving professional support [56].

Limitations

The primary limitations in this study were the small sample and the lack of the research participants’ gender diversity, indicating that the findings cannot be generalized. Lack of having women who were willing to participate in this study may have come from high addiction related stigma and stereotypes in women. Therefore, all the participants were men, and this limited the depth and breadth of our understanding of the lived experiences of people in longterm recovery from alcohol use disorder. Another limitation of the study is that it was limited to alcohol recovery and, therefore, excluded recovery from other drugs.

Implications

Despite differences in conceptualizing recovery, not overusing alcohol is a hope for millions of people [58, 59]. Although there are millions of people recovering from substance abuse, studies that investigate what supports long-term recovery are limited [22]. Most research is done in treatment facilities and the reality is many persons do not use or have access to formal treatment, but we can learn from them. The findings from this research offers knowledge about in-depth insight into longer term recovery journeys and is beneficial to inform practitioners and other interested groups to assist people to recover from alcohol use disorder. At the time this study was done, there was not a single study conducted in Ethiopia to understand the experience of people with ten or more years of recovery from alcohol use disorder. This research bridges a gap in long term recovery and serves as a foundation for developing a culturally relevant framework for understanding recovery that is Afro-centric and specifically Ethiopian. For counselors in practice and counselor educators it is important to hear stories of persons struggling with alcohol use disorder. This listening sets a strong foundation for conducting a comprehensive assessment of the physical, social, emotional, spiritual, and financial consequences of their problem alcohol use. Stories themselves can be assessment tools; they are about change and serve to be recovery strategies themselves. In addition, stories are powerful, and a core part of recovery. The stories told in AA is one of the reasons it can be such a beneficial experience for many participants. One of the ways people sustain their recovery is by sharing their stories and become role models to others. Counselors need to work with religious leaders, community figures, journalists, teachers and other professionals to create opportunities for people in recovery to share their recovery journeys with others [60-68].

It is important to understand how one views recovery. Recovery is more than abstaining from alcohol; people in recovery have different meanings and values for it including “life,” “heaven,” “rebirth,” and “reliving.” Sustaining recovery is linked with establishing and maintaining connections. It is wise for counselors and supervisors to know that clients maintain their recovery when they restore or maintain connections with themselves, their families, and communities. Contribution can give meaning and purpose to life. A big part of recovery is engaging in humanitarian and giving back work. Addiction counselors and health professionals need to encourage their clients explore ways to get involved in giving back activities and stay connected with their community. Service learning can provide many benefits. All humans have strengths. Lived experiences descriptions indicate that recovery is less about blaming oneself for past mistakes and destructions and more about building on the current accomplishments, self-efficacy, assertiveness, and commitment. Hence, clients’ self-work remains an important focus in addictions counseling. Recovery is more than just abstaining from use of alcohol and drugs; it is about gaining freedom to live, love, and belong.

Future Research

This study explored the lived experiences of people in longterm recovery from alcohol use disorder in Ethiopia. There could be studies investigating the lived experiences of longterm recovery from other drugs. Another research opportunity for future researchers is to incorporate women in their lived experience studies. Since this study explored the lived experiences of six men in alcohol long-term recovery, future studies can expand upon this research and increase understanding of women in longterm recovery from alcohol and other drugs. As the scope of the present study was limited to people in alcohol recovery in Ethiopia, future researchers might include people in long-term recovery from alcohol and other drugs from different countries to increase understanding of recovery lived experiences cross-culturally.

Conclusion

It seems that no matter where the location, the experiences of recovery are important. They go beyond the walls of one country. Recovery, while not universally defined, is complex and multilayered. Being in recovery includes maintaining self-work; having better stress coping mechanisms; changing role models, routines, and lifestyles; getting involved in passionate activities; having new goals, purposes, visions, and dreams; and giving back to the society.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2013) Results from the 2012 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings.

- Abebe D, Debella A, Dejene A, Degefa A, Abebe A, et al. (2005) Khat chewing habit as a possible risk behavior for HIV infection: A casecontrol study. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 19: 174-181.

- Alem A, Kebede D, Kullgren G (1999) The prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of khat chewing in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 397: 84-91.

- Alem A, Teshome S (1997) Khat induced psychosis and its medico-legal implications: A case report. Ethiopian Medical Journal 35(2): 137-141.

- Fekadu A, Alem A, Hanlon C (2007a) Alcohol and drug abuse in Ethiopia: Past, present and future. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies 61: 39-53.

- Gelaw Y, Haile Amlak A (2004) Khat chewing and its socio-demographic correlates among the staff of Jimma University. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 18: 179-183.

- Gelaw Y, Haile Amlak A (2004) Khat chewing and its socio-demographic correlates among the staff of Jimma University. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 18: 179-183.

- World Health Organization (2004) Global Status Report on Alcohol. Country profiles.

- World Health Organization (2010) Resource for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. Atlas on substance use.

- Patel V (2007) Alcohol use and mental health in developing countries. Annals of Epidemiology 17(5S): S87-S92.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2013) Alcohol and public health: Alcohol- related disease impact.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2012) Alcohol use and health.

- National Drug Intelligence Center [NDIC] (2010) Impacts of drug on society.

- NIDA (2008) Addiction science: From molecules to managed care.

- Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B (2010) Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse Negl 34(6): 454-464.

- Conner K, Beautrias A, Conwell Y (2003) Risk factors for suicide and medically serious suicide attempts among alcoholics: Analyses of canterbury suicide project data. J Stud Alcohol 64(4): 551-554.

- Down ET, Rugle L (2007) Substance abuse: A practitioner guide to comparative treatments.

- Felitti VJ (2009) Adverse childhood experiences and adult death. Academic Pediatrics 9: 131-132.

- Schaffer M, Jeglic EL, Stanley B (2008) The relationship between suicide behavior, ideation, and binge drinking among college students. Arch Suicide Res 12(2): 124-132.

- Singleton RA, Wolfson AR (2009) Alcohol consumption, sleep, and academic performance among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drug 70(3): 355- 363.

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H (2000) College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of public health 1999 college alcohol study. Journal of American College Health 48(5): 199-210.

- Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR (2001) A longitudinal model of intake symptomatology, AA participation and outcome: Retrospective study of the project MATCH outpatient and aftercare samples. J Stud Alcohol 62(6): 817–825.

- Miller WR, Janet C’ De Baca (2001) Quantum change. Guilford Press, New York.

- Kelly JF, White WI (2012) Broadening the base of addictions mutualhelp organizations. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery 7(2-4): 82-101.

- Moos RH (2003) Addictive disorders in context: Principles and puzzles of effective treatment and recovery. Psychol Addict Behav 17(1): 3-12.

- Galanter M, Josipovic Z, Dermatis H, Weber J, Millard MA (2016) An initial fMRI study on neural correlates of prayer in members of Alcoholics Anonymous. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1-11.

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, Walker D (2005) Mindfullness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disorders. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly 3: 211-228.

- Morgan TB, Crane RD (2010) Cost-effectiveness of family-based substance abuse treatment. J Marital Fam Ther 36(4): 486-498.

- Pruett JM, Nishimura NJ, Priest R (2007) The role of meditation in addiction recovery. Counseling and Values 52: 71-84.

- Warren J (2012) Applying Buddhist practices to recovery: What I learned from skiing with a little Buddha wisdom. Journal of Addictions and Offender Counseling 33(1): 34-47.

- Koch DS, Sneed Z, Davis SJ, Benshoff JJ (2007) A pilot study of the relationship between counselor trainees’ characteristics and attitudes toward substance abuse. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions 5: 97-100.

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, et al. (2008) A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 165(2): 179-187.

- El Guebaly N (2012) The meanings of recovery from addiction: Evolution and promises. J Addict Med 6(1): 1-9.

- Witbrodt J, Kaskutas LA, Grella CE (2015) How do recovery definitions distinguish recovering individuals? Five typologies. Drug Alcohol Depend 148: 109-117.

- Betty Ford Center (2010) What is the difference between alcohol abuse and dependence?

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. 5th(edn), American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Merriam SB (2009) Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. The Jossey-Bass, USA.

- Green J, Thorogood N (2014) Qualitative methods for health research. Sage, UK.

- Liamputtong P (2013) Qualitative research methods 4th (edn.). Oxford University Press, Australia.

- Silverman HJ (1994) Textualities: Between hermeneutics and deconstruction. Routledge Press, New York.

- Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A (2011) Qualitative research methods. Sage, UK.

- Mc Kim C, Warren J, Asfaw AH, Balich R, Nolte M, et al. (2014) An integrative model of recovery: A qualitative study of the perceptions of six counseling doctoral students. RPBS 2(1): 17-23.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage, USA.

- Cohen MZ, Kahn DL, Steeves RH (2000) Hermeneutic phenomenology research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. In: International Education and Professional Publisher, UK.

- Kafle NP (2011) Hermeneutic phenomenological research method simplified. Bodhi: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5(1): 181-200.

- Ajjawi R, Higgs J (2007) Using hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate how experienced practitioners learn to communicate clinical reasoning. The Qualitative Report 12: 612-638.

- Grbich C (2013) Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Sage, UK.

- Duque RL (2009) Review: Catherine Kohler Riessman. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 11(1).

- Author (2015).

- Laudet A, Morgen K, White W (2006) The role of social supports, spirituality and affiliation in 12-step groups in life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug use. Alcohol Treat Q 24(1- 2): 33-73.

- White WL (2007) Addiction recovery: Its definition and conceptual boundaries. J Subst Abuse Treat 33(3): 229-241.

- White WL, Kurtz E (2006) The Varieties of Recovery Experience: A Primer for Addiction Treatment Professionals and Recovery Advocates. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care 3(1-2): 21-61

- White WL (2004) Addiction recovery mutual aid groups: An enduring international phenomenon. Addiction 99(5): 532-553.

- Laudet AB (2007) What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. J Subst Abuse Treat 33(3): 243–256.

- Laudet AB (2007) What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. J Subst Abuse Treat 33(3): 243–256.

- Rebgetz S, Hides L, Kavanagh D, Choudhary A (2015) Natural recovery from cannabis use in people with psychosis: A qualitative study. J Dual Diagn 11(3-4): 179-183.

- Spinelli C, Thyer BA (2017) Is recovery from alcoholism without treatment possible? A review of literature. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 35(4): 426-444.

- Koehn C, Cutcliffe JR (2012) The inspiration of hope in substance abuse counseling. Journal of Humanistic Counseling 51: 78-98.

- Larsen DJ, Stege R (2011) Client accounts of hope in early counseling sessions: A qualitative study. Journal of Counseling and Development 90(1): 45-54.

- Brownell KD, Marlatt GA, Lichtenstein E, Wilson G T (1986) Understanding and preventing relapse. Am Psychol 41(7): 765-782.

- De Pue MK, Finch AJ, & Nation M (2014) The bottoming-out experience and the turning point: A phenomenology of the cognitive shift from drinker to nondrinker. Journal of Addictions and Offender Counseling 35: 38-56.

- Domino KB, Hornbein TF, Polissar NL, Renner G, Johnson J, et al. (2005) Risk factors for relapse in health care professionals with substance use disorders. JAMA 293(12): 1453-1460.

- Fekadu A, Desta M, Alem A, Prince M (2007b) A descriptive analysis of admissions to Amanuel Psychiatric Hospital in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health and Development 21: 173-178.

- Fetting M (2012) Perspectives on addiction: An integrative treatment model with clinical case studies, USA.

- Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA (1999) Relapse prevention: Overview of Marlatt’s cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Res Health 23(2): 151-160.

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL (2004) Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 291(10): 1238-1245.

- NIAAA (1997) Ninth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. Department of Health and Human Services, USA.

- Whitesell M, Bachand A, Peei J, Brown M (2013) Familial, social, and individual factors contributing to risk for adolescent substance use. J Addict.

-

Amanuel Haile Asfaw, Jane Warren. Alcohol Use Disorder Recovery in Ethiopia. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 2(4): 2019. OAJAP. MS.ID.000542.

Alcohol use disorder, Long-term recovery, Hermeneutic phenomenology, Alcohol abuse, Alcoholics, Behavioral Therapy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.