Research Article

Research Article

Decoding Prehistoric Art: The Principles of Natural Philosophy on the Tablet of Shamash

Prof. Vahanyan G*

Prof., Doctor of Knowledge Management of the European University in Armenia

Prof. Vahanyan G, Prof., Doctor of Knowledge Management of the European University in Armenia

Received Date: September 27, 2022; Published Date: November 03, 2022

Preface

The methodological basis of our research covers the conception of the model of a clay “vase” (Greek Krater, amphora). Suppose a teacher has made a krater, beautiful in its form and ornamentation. Let name it Noah’s Krater. Three craftsmen has made three new kraters from the same clay in the image and likeness of the original. Let name them the Kraters of Shem, Ham and Japheth. New craftsmen have kept on the traditions of their teachers, creating copies of the Kraters of Shem, Ham and Japheth before the confusion of tongues (according to Biblical tradition), before the construction of the Tower of Babel and Hayk’s resettlement from Babylon (his son was born in Babylon) to the land of his forefathers, to the destroyed house of Askanaz and Torgom (according to Armenian tradition). Hayk and his rival Bel revered one teaching. Yet Bel deviated from this teaching and decided to hold the power and rule the world, imposing his will, introducing idolatry and challenging the Lord.

Suppose, all the kraters are devided into hundreds and thousands of pieces. Each of them might contain a fragment (element) of the ornamental motif, decorating “Noah’s Krater”. It is disputable which of the pieces has better and more intensively preserved the depiction of the motif of the ornament of Noah’s Krater. The article studies the Krater of the first man, the archetype of the further formed Kraters, rather than Noah’s Krater. In the myths clay is considered as the material for the Krater of the first man1. According to Ancient Greek mythology, man was created from clay in the Caucasus by Prometheus.

Foot Notes

1 Vahanyan G., Vahanyan V., Baghdasaryan V. Cognitive meaning, form and conceptual content of the notion “Caucasus”. IV International Congress Of Caucasiologists “Scripts in the Caucasus”, Tbilisi, 1-3 December 2016, http://www.iatp.am/vahanyan/articles/kavkaz-tbilisi-2016-ru.pdf

Vahanyan G., Vahanyan V., Baghdasaryan V. All Arts of Mortals from One Teacher Spring, http://www.iatp.am/-vahanyan/articles/uchenievahagna2017- ru.pdf

The authors have identified that the fragments from the ornamental motif of Noah’s Krater are better preserved on the pieces of Hayk’s Krater. Resettleing in the land of Torgom, Hayk builts the dwelling of God (temple of knowledge). He fights tyrant Bel on this very land and defeats him; later he buries his kinsman with honor at the crater of a volcanic mountain in the vicinity of Lake Van, emphasizing the renaissance of the teaching of his father, i.e. values and traditions of Noah. Thus, the symbols of the teaching of Hayk’s Krater, as well as his language (speech), are the symbols and the language of Torgom (who renamed the house of Askanaz into the house of Torgom) and Askanaz (his elder brother), Tiras (Hayk’s grandfather), Japheth and Noah.

The analysis of the main motif of the depictions on the Tablet of Shamash2 (found in Babylon), shows that the Tablet of Shamash has preserved the sacred values of Hayk’s temple of knowledge. It illustrates the principles of Natural Philosophy and Mataphysics known to Askanaz and Torgom. Liberating territories of Babylon, Mesopotamia and Anatolia from the tyrant, Hayk contributed to the transfer of the “new teaching” among the local civilizations and taught them the Armenian speech3. According to the authors, the Armenian language is the true treasurer, intensive repository of knowledge and information regarding the first teachers, motifs of Noah’s and Hayk’s Kraters, the admonitions of the “ark of the covenant”.

The article reveals of the example of decoding of the prehistoric art, including cognitive content of the ancient Babylonian tablet, depicting Shamash in novel frameworks. It portrays high level of cognition of our ancestors, their artistic and visual thinking, profound understanding of the principles of Natural Philosophy and Metaphysics. The tablet of Shamash shows the paradigms of knowledge, intercultural communication of old civilizations, remaining faithful to the unified teaching4.

New Interpretation of the Tablet of Shamash/Utu

Certain features peculiar to Vahagn5, Indra, Zeus, Shivini and Shamash - the darkness defeaters and cosmos arrangers, allow the authors to distinguish, identify and reconstruct the common cognitive- mythological core of the main motifs. After the destruction of the house of Torgom (the former house of Askanaz)6, the survived inhabitants migrated, taking with them the “kraters” of old knowledge, language, traditions and mythological representations, which were transformed in a new cultural environment, but yet preserved the main features and characteristics.

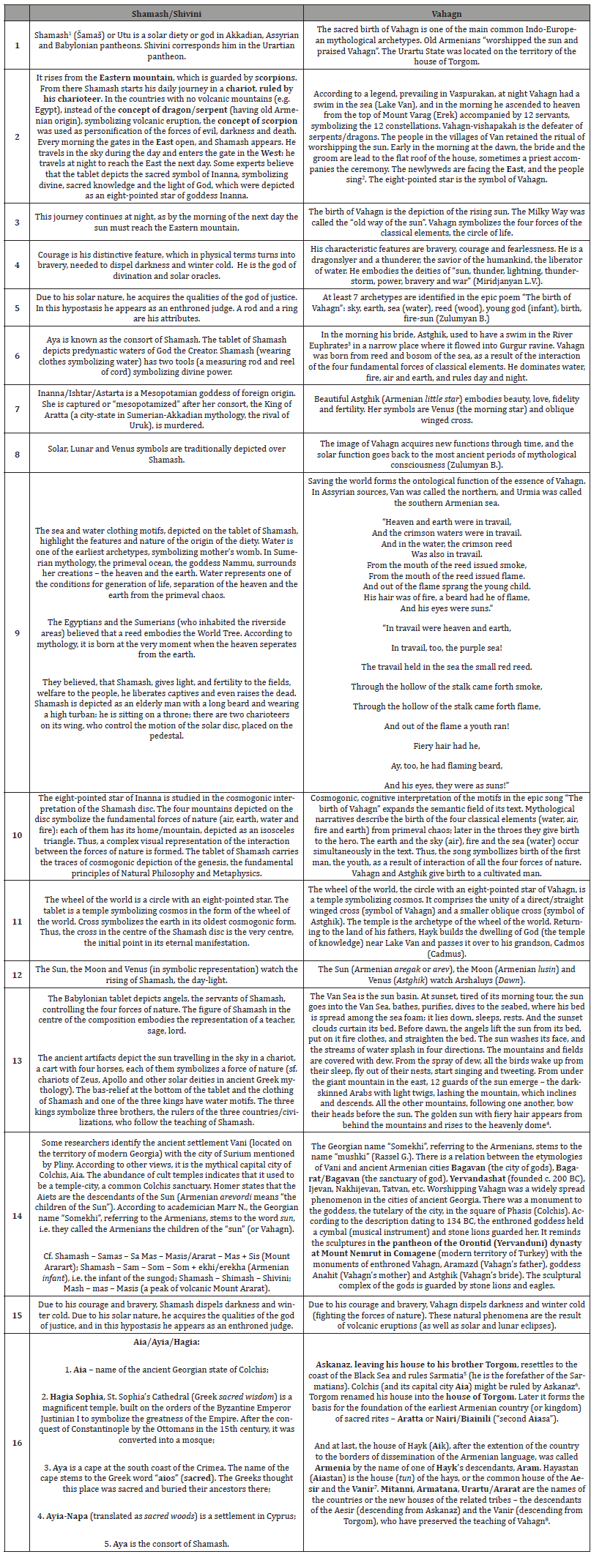

It is widely known, that immediate parallels can be drown between Vahagn and Sumerian Shamash or Utu (cf. Urartu7), as well as with Urartian Shivini. Table 1 shows the comparative characteristics, features and attributes of Shamash/Shivini and Vahagn.

The solar cult in Armenia was observed by Xenophon, who gave his horse to the householder to sacrifice it to the sun. The early hour played an important role in the cult of sun: the time when the “daylight” (cf. Armenian arshaluys meaning “the rising day-light”) was born or rose. It is the Sun rising from the East Mountain, which is guarded vigilantly by the scorpions: here is where Shamash (Sumerian Utu) starts his daily journey in a chariot ruled by his charioteer. This journey does not cease at night, as the sun must reach the Eastern mountain by the morning of the next day.

Utu (Sumerian light, shining, day) is the Sun God. The principle sites of worshipping were Sippar and Larsa. His temples in both cities were called Ebabbar (“white house”). In Sippar Utu was identified with a diety of pre-Sumerian period, considering the fact that Aia is represented as his wife and Bunene – as his son (pre-Sumerian names). The cult of Utu (Shamash) was widely spread especially after the fall of Sumer, when he was worshipped mainly as the god of establishment and application of law8.

As mentioned before, Shamash is the son of the Moon God Nanna (Akkadian Sin) and Ningal (brother of Inanna, Ishtar). His consort is Sumerian Shenirda (or Sudanga) and Akkadian Aia (has an epithet “Aia-bride”; cf. the bride of Vahagn, Astghik); his envoy is Bunene (cf. Biainili or Van). After his daily tour in the sky, Utu hides in the evening and emerges again in the morning from behind the mountains (Mashu, cf. Masis). Usually the two guardian gods show him the way. Utu travels in the underworld, bringing light, water and food to the dead (his Akkadian epithet is “the sun of the dead souls”).

Foot Notes

2 According to the experts, Shamash stems to the Sumerian root Sh-M-Sh (sun).

3 Khorenatsi M. “History of Armenia” // Translation from Grabar and notes: Sargsyan G; Editor: Arevshatyan S. Yerevan, “Hayastan”, 1990.

4 Vahanyan G., Vahanyan V., Baghdasaryan V. The tablet of Shamash and the principles of natural philosophy. Book of abstracts of 20th INTERNATIONAL ROCK ART CONGRESS IFRAO 2018 “Standing on the shoulders of giants / Sulle spalle dei giganti” Valcamonica - Darfo Boario Terme (BS) Italy, 29 August - 2 September 2018.

5 Zulumyan B. Archetype in the pattern of artistic cognition. Monument to Armenian epic poem “The Birth of Vahagn”. Historical-Phylologycal Jpurnal, № 3, 2007, p. 38-55.

6 There are two possible reasons: catastrophic consequences of volcanic eruptions or attacks of the neighbors, the Akkadians and the Sumers. According to the authors, the first version is more persuasive, as in case of the second one Hayk and his family could not have been in a foreign home and have a son in Babylon.

7 In the Armenian language “utu” or “ut-tu” means “give immortality”: the symbol “ut” (Armenian eight) refers to immortality, eternity; cf. Utnapishtim meaning “the hero searching for immortality” (see Vahanyan G. Cultivated heros and their deeds, http://www.iatp.am/news/kamlet/4.pdf).

8 Shamash // The Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary in 86 volumes (82 V. and 4 add.). – Saint Petersburg, 1890-1907.

Table 1:

Foot Notes

1 Shamash/Utu. Encyclopedia of Mythology, http://myfhology.info/gods/shumer/shamash.html

2 The ancient Sumerians believed that Shamash Utu was the Sun God. He was also the all-seeing god of justice, and the god of Sun, justice and oracles in Babylonian-Assyrian religion. A temple of goddess Inanna was built in the city of Uruk (modern Iraq), in the main centre of her cult in 4000- 3100 BC. According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, Shamash is the Sun God in Babylon and Assyria. The ideogram for his name means “the master of the day”. As the god of the second half of the day (beginning in the evening), he concedes to the Moon God, Sin, and was even called his servant. His main cults were at Sippar and Elassar, where his temple stood in V millennium.

3 Miridjanyan L. “The origin of Armenian poetry”, http://armenianhouse.org/mirijanyan/armenian-poetry/2.html

4 It emerges in the mountains of the Armenian Highlands from the confluence of two rivers: Kara Su (Western Euphrates), with its source in the north of Erzurum, and Murat (Eastern Euphrates), with its source in the southwest of Mount Ararat and in the north of Lake Van. The first Sumerian civilizations emerged in the vicinity of Euphrates from c. IV millennium BC. Many important ancient cities were located here: Mari, Sippar, Nippur, Shuruppak, Uruk, Ur and Eridu. The centres of later empires, Babylonia and Assyria, emerged in the river valley. According to Khorenatsi M., the house of Askanaz (house of Torgom) was built at the riverbank.

5 Harutyunyan S. The motifs of Armenian mythology. Translated by Ghazaryan M. Armenian mythology. “Arevik”, Yerevan, 1987, http://www.

armenianhouse.org/harutyunyan/armenian-myths-legends.html6 In “Geography”, Shirakatsi mentions European and Asian Sarmatias.

7 According to the authors’ hypothesis, the new house of Askanaz (or its part) was later called Hayasa (the country of those who speak the language of Askanaz, the Aesir (aies) or hays, i.e. the Armenian language).

The role of Shamash in Akkadian cult is more significant than that of Sumerian Utu. The Utu cult evolved in Uruk. Utu is the founder of the first dynasty of Uruk. Utu is particularly notable in mythical- poetic tradition of Uruk. Utu is the guardian and tutelary god of epic heroes. In an Akkadian myth of Etana, Shamash is a judge, helping the serpent to wreak vengeance on the eagle for violation of the oath; he also assists Etana to save the eagle. The cult of the Sun God is located in the city of Sippar in the north, and in Larsa – in the south. A public temple with lunar diety in Ashura was dedicated to Shamash. The Sun God is more often depicted in iconography, on reliefs and glyptics, rising from behind the mountains. Trials of Utu (Shamash) over different mythical creatures are also depicted. The distinctive features of the god are rays rising from his shoulders and a semilunar saw-toothed knife in his hands9. The tablet of Shamash (length: 29.2 cm, width: 17.8 cm, serrated borders; Neo-Babylonian period, 626-539 BC), placed in an earthenware casket, was discovered during excavations between 1878 and 1883 in Sippar (modern southern Iraq), broken into two large and six small pieces. It is now the British Museum heritage. The tablet was venerated and was possibly kept due to the development of new traditions. In Urartian pantheon Shivini10 corresponds him. Many features of Shamash were transformed into the concept of Mitra . This approach, according to the authors, is outdated and requires revising: many features and characteristics of Vahagn were initially transformed into the concept of Shamash/Shivini, being the prototype of formation of the concept of Mitra11. According to the traditional view of the researchers, the bas-relief on the top of the adverse of the tablet of Shamash (Figure 1) shows Shamash beneath symbols of the Sun, Moon and Venus. He is depicted enthroned in a shrine/tomb, holding forward a disc and a rod (symbols of power). There is another large disc in front of Shamash on an altar, suspended from above on a cord. Of the three kings, the tallest one is dressed the same way as Shamash.

Foot Notes

9 Afanasieva V. K. World Myths // Utu, http://astroschool.pro/?amp;dic_tid=4174&q=myphology-dictionary&-dic_ltr=0KM=&dic_tid=4185

10 Urartu/Ararat (9-7 centuries BC).

11 Mitra1 is the deity of agreement and sun in Iranian, Vedic and Armenian mythologies. Mitre is a type of headgear, ceremonial head-dress of bishops

and certain abbots in traditional Christianity. In the last centuries BC, emerged the cult of Mithra, Mithraism, which was widely spread in Hellenistic

period, from I century AC in Rome, from II century AC in the Roman Empire. It was popular in the border provinces, where the Roman legions

worshipped Mithra, the god bringing victory. There are a number of sanctuary Mithraeums in the

The cuneiform text beneath the stele tells how Sippar and the temple of Shamash had fallen into disrepair with the loss of the statue of the God. This cult image is temporarily replaced with the solar disc. It should be mentioned that the Tablet of Shamash was discovered in an eastern part of the Euphrates , where his statue of lapis lazuli and gold used to stand.

The traditional interpretation of the content of the tablet is admitted by the experts in history of art of Ancient Near East13. Some experts think that a sacred symbol of Inanna, symbolizing divine sacred knowledge and light of the God, is depicted on the tablet. Embodied in an eight-pointed star of goddess Inanna, they were passed to the king, personifying sacred powers. According to them, the tablet depicts pre-dynastic waters of God the Creator.

The cross in a circle is one of the earliest symbols14. Circle is the symbol of both the beginning and the end, it is a complete form, embodying the appearance cycle. The cross in a circle symbolizes cosmos or the world divided into four parts15: the vertical line denotes masculine, spiritual principle, and the horizontal line in a circle denotes matter or feminine principle. Considering the immutable aspect of perpetual motion (see the rope stretched on Shamash’s disc, Figure 1) along with this symbol, the wheel of the world or the swastika are formed. The cross in a circle and the wheel are often identified in Armenian rock art. The ancient inhabitants of the house of Torgom (and Askanaz) knew about the existence of this cosmic symbol long before the appearance of the great Egyptian pyramids16.

authors present another interpretation of the cross in a circle: the circle is considered as a symbol of watersource, as a life-giving environment; the cross symbolizes birth, the winged direct cross (symbol of Vahagn) symbolizes masculine, spiritual principle, and the winged oblique cross symbolizes feminine principle (symbol of Astghik). Their unity (family) is depicted in the representation of an eight-pointed star, symbolizing life, fertility and love.

The complex composition of their union is a visualization of the concept of perpetual motion of the wheel of the world. The winged cross in a circle is a symbol characterizing the interaction of the four forces of nature17. The fundamental principles of Natural Philosophy and Metaphysics18 are implemented in the epic song “The birth of Vahagn”. It is not a coincidence, that the concept “home” in Armenian rock art and ideograms is represented in the form of a mountain, isosceles triangle19. This figure was used in diverse artifacts, ceramics, miniatures, rug and carpet design, decorative arts, household items, weapons, etc.

According to mythology, “dragons/serpents lived” in the Araratian mountains. Their images embodied or modeled natural phenomena: volcanic eruptions and avalanches. These motifs are preserved in folk songs, legends and myths, they have become the evidence of the severe struggle of a premeval man against natural phenomena for survival and development. They are implemented in the culutural traditions, the representation of mythological and religious description of the world, moreover, in the process of intercultural communication they were disseminated with language with nearly no modifications.

The tablet of Shamash depicts typical old Armenian ornamental tradition. It comprises visual motifs of the following concepts: home, family, cross, star, birth (interaction and unity of the fundamental forces of nature, representing the principles of Natural Philosophy and Metaphysics), genesis, struggle against the evil – the serpent, guarding the source of life, sea (the environment of birth), power (cf. Armenian astvats, Astghik, Hayastan, astitshan), rule, the wheel of the world, heavenly angels, sunlight, etc. The tablet of Shamash depicts a stylized cross comprising four houses, symbolizing the four forces of the classical elements: fire, water, air and earth (Figure 1). The star consists of four image clusters of wavy lines – the symbols of water and feminine prin-ciple. These depictions are associated with the symbols of the concept of Astghik, the oblicque cross. Graphic representation of the clusters of wavy lines simultaneously model the sources of the four rivers from a single unity, ecumene of Van Sea, the Araratian mountains20, described in the Bible. It is evident, that the figure of Shamash in the centre of the composition symbolizes the teacher, sage, judge. This corresponds to the features of the image of Vahagn (analogous to solar diety in pagan period). The three kings are the students or the children of Shamash, possibly, the three bogatyrs, born on Mount Masis/Ararat (according to Azhdahak’s dream ). They might as well be Noah’s sons, embodying the resettled Shem and Ham, and Japheth who did not leave the house of his father.

Foot Notes

12 Euphrates (Greek and Latin Euphrates; Hebrew Perat; Armenian Yeprat and Aratsani; Arabic Furat; Old Persian Iphratu) is the greatest river of the Near East, forming its main river system together with the River Thigris. In the Armenian Highlands, it comprises two deep rivers: the shortest (Western) flows from the north and formed the eastern border of the Roman Empire for centuries; and Murat Su (Murâd-Su), the longest (Eastern) flows from Armenia. The source of the first one is located 37 km to the northeastern Erzurum, and the source of the second one lies to the southwestern Diadina, to the north of Lake Van, in Aladagh (2750 m).

13 Woods C.E. 2004. The Sun-God Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina Revisited, JCS 56, p. 23 – 103.

14 Cross and swastika are the most used symbols in the tradition of Armenian rock art.

15 Toramanyan T. Zvartnots. Yerevan, Publishing House “Sovetakan Grogh”, 1978.

16 Tokarskiy N. M. Armenian Architecturee of IV – XIV centuries. Yerevan, Publishing House “Armgosizdat”, 1961.

17 Vahanyan V., Ghazaryan O. Transformation of plant and animal motives in Armenian Medieval (IX-XIV centuries) ornamental art. Monograph, “Astghik Gratun”, Yerevan, 2016, 256 p.

18 Vahanyan G., Vahanyan V. Armenian Rock Art: the Origin of Natural Philosophy and Metaphysics. EXPRESSION N°6. 2014. Quaterly e-journal of Atelier in Cooperation with UISPP, Italy.

19 Vahanyan G., Vahanyan V., Baghdasaryan V. Cognitive aspects of the concept “home”, http://www.iatp.am/vahanyan/ articles/uchenie-vahagna2017- ru.pdf. Book of abstracts of 20th INTERNATIONAL ROCK ART CONGRESS IFRAO 2018 “Standing on the shoulders of giants / Sulle spalle dei giganti” Valcamonica - Darfo Boario Terme (BS) Italy, 29 August - 2 September 2018.

20 According to the Biblical teaching, after the genesis, the first man was settled in the Eden. After the flood, the Noah’s Ark (as a unique temple of knowledge) came to rest on the Araratian mountains.

A serpent figure (Figure 1), in the form of a heaven ideogram, is depicted above Shamash. It rises from the seabed; its head is depicted above the column, possibly erected in honor of victory over the forces of evil and darkness. The column stretches to the very sky, at the bottom it has plant motifs and is located over the sea. The top of the column is also decorated with plant motifs. The surface of the column is covered with stylized serpent/dragon scale. Shamash’s headgear reminds a Phrygian cap, a distinctive attribute of Tiras (father of Askanaz and Torgom), who moved to Phrygia (Thrace). The cap passed over to his descendants (Phrygian warriors), to the image of Mitra22 and to the kings of Armenian Orontid (Yervanduni) dynasty. Shamash is holding a circle/disc with a rod in his left hand. They symbolize divine power. A similar sign is identified in Akkad, Sumer, ancient Kingdom of Comagene, Assyria, Urartu and Egypt. Goddess Inanna is holding similar discs and rods. The Assyrian and Urartian artifacts depict the heroes inside discs. A disc or a circle, as mentioned before, reflect the concept or the idea of both the source of life and united power23 (арм. akunk – ak [disc] and unk [brow]).

The features of Vahagn were transformed into the image of Shamash (Figure 1), and the features of Shamash – that of Mitra. Ornamental fragments from the tablet of Shamash are identified in symbols of nearly every early civilization (Caucasus and Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylon, Hittites and Egypt, Persia and India, Old Europe and Greece, Germany and Nordic countries)24. During the Roman Empire, the Sun God symbols were associated with the symbols of Mitra and Baal25. Still they have old Armenian, Araratian origin and are attributes of the temple of knowledge, built by Hayk.

Of particular interest is the symbol of Mitra’s “birth” from a stone and his “struggle” with a bull: “Mitra, turning away his face, stubs a knife into the victim’s side. When a bull dies, spewing out semen (a scorpion is gnawing the bull’s phallus), a seed grows from its brain that gives bread, and a vine from its blood …” Sina, whose symbol was the crescent moon, was considered wise, and it was believed that, when increasing and waning, the Moon God measured time…”. It should be mentioned that in Armenian tradition Hayk’s rival, Bel, was depicted as a bull. The motifs of birth and struggle of Mitra stem to the transformation of old Armenian motifs26 : the motifs of birth from a rock/stone and of volcanic eruption (scorpion or serpent )27, of water liberation and fertility, of struggle and victory over the vishap/serpent.

Foot Notes

21 Khorenatsi M. History of Armenia, translation from Grabar: Sargsyan G. “Hayastan”, Yerevan, Armenia, 1990.

22 Plutarch writes that the spread of the mysteries of Mithras over the Mediterranean is connected with the activity of the Cilician pirates in the 60s BC.

Mircea Eliade believes that the legendary details of the biography of Mithridates VI of Pontus (and of Cyrus the Great) reflect the representations of Mithraism. According to the mysteries, Mithra was born from stone, and the mysteries are committed in a cave. According to Statius, the Achaemenians call Apollo a Titan, and in the cave of Perseus he is called Mithra, bending the horns. Porphyry notes that Zoroaster was the first to dedicate to Mithra the cave in the mountains, blooming and rich in springs. This cave symbolizes the cosmos created by Mithra, and the inside is the symbol of cosmic elements and cardinal directions (similarly, according to Porphyry, Plato related cosmos to the Pythagorean cave). Mitra wears the sword of Aries (the sign of Ares) and rides the bull of Aphrodite. If the cave is considered as a house/mountain/temple, with an eight-pointed star of Vahagn inside the temple, it will reflect the four cosmic classical elements and the four cardinal directions (authors’ note). According to Tertullian, in the sacraments of Mithra, the offering of bread was performed and the image of the resurrection was presented. According to Celsus, the mysteries present the symbols of motion of stars and planets and the passage of souls through them, with the seven-gate stairway as its symbol (seven gates are connected with seven metals and seven deities). He claims that the Christians borrowed much from this teaching. According to Claudian, Mithra is called rotating the stars, and the emperor Julian the Apostate mentions the secret Chaldean teaching of seven rays. Since the end of II century, Roman emperors (Aurelian and Diocletian) patronized the cult of Mithras. In II-IV centuries, Mithraism was one of the main rivals of Christianity.23 According to the Bible, Moses threw down the staff, and it turned into a snake.

24 Vahanyan G., Vahanyan V. Vanaland, Scandinavia and Russ (the path to self-awareness), ArcaLer, 15.11.2013, http://www.iatp.am/vahanyan/ articles/vanaland.pdf

24 Vahanyan V., Vahanyan G. Intercultural relations between Old Europe and Old Armenia. XXIII Valcamonica Symposium “Making history of prehistory, the role of rock art”, 28 October - 2 November 2009, Italy.

25 Baal (in the Semitic Languages Bl, Old Hebrew Bel, Balu) was a title and honorific meaning “lord”. Emperor Elagabalus transferred his cult to Rome. Baal Hammon is the Sun God. In Carthage he was one of the main gods. The Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD) banned the human sacrifices to Mithras and Baal in the Roman Empire. Vatican was built on the shrine previously dedicated to the worship of Mithras (600 BC). The Orthodox Christian hierarchy is almost identical to the version of Mithras. Almost all the elements of Orthodox rites, e.g. water baptism and doxology, were adopted from Mithra.

26 Vahanyan V., Vahanyan G. All arts of mortals from one teacher spring, ArcaLer, 2017 http://www.iatp.am/vahanyan/articles/uchenie-vahagna2017- ru.pdf

27 Scorpion is used instead of the symbol of dragon/vishap/serpent in areas where there were no volcanic eruptions, e.g. in Egypt or Mesopotamia. The concept of Bull is replaced by the concept of vishap (dragon). Vahagn defeats the earthly and heavenly dragons, liberates waters that flow from his body. Vahagn liberates waters, the source of which was guarded by the dragon (in the Akkadian and Egyptian traditions, a scorpion guards the Eastern Mountain, the source of the Rivers Tigris and Euphrates). The melting of the snow in the Armenian mountains in May causes an overflow in the Rivers Tigris and Euphrates: the waters protrude from the shores and flood the plains, moisturizing and enriching them with silt. This was used for irrigation purposes. In ancient period, Euphrates used to be the main communication and commercial artery between peoples and cities near the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf. Trade incomes here reached enormous amounts (Herodotus, I, 185). Euphrates and Tigris are mentioned in the Bible as two of the rivers in Eden, or Paradise (Gen., 2, 14, etc.).

The Ancient Greeks thought that Colchis was the territory at the Black Sea shore and the name of the country. In the Abaza language, the word Kolkhita is translated as “auriferous country (land)”28. In the Ubykh community of Vardan, in the Black Sea region, there was a village called Hiza Sev (name of a month). Pahu is the name of the area where the fortress of Aia Bga (rock, cliff) was built. N(y) is an ancient form of an independent word, used for defining a country, a land. Hence - Bgany, meaning the land of rocks. This is how the mountainous part of Ashui was called in ancient times. Kh(y)n(y) means the “golden land”.

King Aiet considered himself a descendant (son) of great Marana - the Sun God. In а Greek myth, Aeetes is the son of the Sun God (Greek Helios). According to Turchaninov29, this cannot be a mere coincidence. Probably, calling himself the son of King Ptu (people called him Marana), Aiet was considered the descendant of Helios in Greek mythology as well. Colchis30 could be influenced by prehistoric Hayasa (the country of the descendants of Askanaz) or Aratta (the country of the descendants of Torgom). Hayk lived in Babylon for a particular period. It is known that in Sumerian-Akkadian mythology, Marduk is the supreme deity in the pantheons of Babylonia and Ancient Mesopotamia, the tutelary god of the city of Babylon. In ancient Egypt the names of the pharaohs were often inscribed into a Shen ring, which was called a cartouche. Shen was graphically depicted as a cord with intersecting edges, which formed a tanget to a circle, as depicted in the Mesopotamian tablet in the hands of god Shamash.

Visual model of the concept mountain/home/tun/ glkhatun

In the Armenian tradition the mountain formation is usually anthropomorphous. According to some myths, mountains used to be giant brothers. Every morning they tightened their belts and greeted each other. But over time, they got lazy to get up early, and greeted each other not tightening their belts. The gods punished the brothers and turned them into mountains, and their belts - into green valleys, and their tears – into springs. According to another version, the mountains Masis (Ararat) and Aragats used to be sisters, and Zagros and Taurus used to be horned vishaps (dragons) fighting among themselves.

Figure 2 shows a typical Armenian house/glkhatun. It forms a square ground or semi-underground construction with no windows, with walls made of crude stone and with pyramid-shaped overlap, supported by an internal pillar frame, with a chimney in the centre. In “Anabasis”, Xenophon31 was the first to give the description of the prototype of the dwelling, who visited the region during the Greek campaign. Speaking about what he saw, he noted: “The houses were underground structures with an aperture like the mouth of a well by which to enter, but they were broad and spacious below. The entrance for the beasts of burden was dug out, but the human occupants descended by a ladder.” Such houses are discovered during the excavation in Catalhoyuk. Figure 2 shows the schemes of glkhatun made of stone (a), clay (b) and volcanic mountain (c). Figure 3 shows the scheme of a house/mountain/glkhatun – a burial vault, kurgan/tumulu, built by Antiochus (from the Orontid [Yervanduni] dynasty, the decendants of Hayk and Vahagn), the king of the Kingdom of Comagene (territory of modern Turkey)32. Various solutions for the traditional overlapping of glkhatun – azarashen33, were obtained depending on the region. In particular regions of historical Armenia, the residential and household sections of glkhatun were located in the same construction, in warmer regions they were located separately. The lighting of the dwelling came through an aperture for the chimney (erdik) in the ceiling.

Foot Notes

28 Turchaninova G.F. Monuments of script and peoples of the Caucasus and Eastern Europe, Science, 1971. In the Postscriptum to the book, the author mentions his discovery: the script that he called “Colchian” and interpreted as having Phoenician origin, turned out to be local, created in the north-western Caucasus. This scientific fact convincingly demonstrates the authenticity of the historical data, stated by M. Khorenatsi in the “History of Armenia”. For example, historical data about Tiras (the father of Askanaz and Torgom), the god of writing, science and divination; and about Cadmus, the grandson of Hayk, who inherited the dwelling of the god (the temple of knowledge). According to Herodotus, Cadmus created the Phoenician and Greek alphabets. The Greeks, having stolen the Golden Fleece from Colchis, obtained a script system, enabling them to decode ancient knowledge.

29 Turchaninova G.F. The discovery and deciphering of the earliest script of the Caucasus. Institute of Languages of RAS, Moscow Research Centre of Abkhazian Studies, Moscow, 1999, 263 p.

30 According to Apollonius of Rhodes (second half of III century BC), the “Argonautica” reflects the events of the end of II millennium BC: “...the people of the capital of the Colchis Kingdom, Aea, retain the records of their fathers made on tablets, which show all the paths of water and land for travelers”.

31 Xenophon. Anabasis // Chapter V, http://www.vehi.net/istoriya/grecia/ksenofont/anabazis/01.html

32 In the 40s of I century BC, Antiochus I of Commagene built a fifty-meter-high sanctuary tumulus at the top of Mount Nemrut, with four artificial terraces, monuments, constructions and inscriptions. In the eastern and western terraces there are five stone figures (8-9 m) of enthroned gods.

33 Loburdette J., Ausias D. Armenia. - Le Petit Futé, 2007. - p. 66. Bulletin of Social Sciences, Issues 1-6 // Publishing House of the AS of Armenian SSR, 1982.

There was a clay oven in the ground – tonir, and a wall mounted fireplace – bukhari. Gomi-oda, a room for accepting guests or men’s gatherings, separated from the room for cattle by a thick wall partition, was typical for Western Armenia. The shape of a glkhatun was used by Armenian architects in the construction of cult buildings, in particular church nartexes (gavits). The sanctuary monumental tomb (Figure 3), built by king Antiochus I from Comagene in 62 BC, includes sculptures of heroes/gods surrounded by huge statues and animals (lions and eagles)34. These animals are often identified in rock art, heraldry, reliefs of medieval Armenian monasteries and churches35.

Conclusion

The tablet of Shamash illustrates the principles of Natural Philosophy and reflects the concept of ruling the four forces of nature (fire, air, water and earth). Each of them is visually represented as a triangle- home-mountain. The wheel of the world is the transformed composition of old Armenian eight-pointed star, the symbol of Vahagn and Astghik. The four triangles symbolize the direct cross – the symbol of Vahagn, and water streams symbolize the oblicque cross – the symbol of Astghik.

Foot Notes

2 Vahanyan V., Vahanyan G. Tomb-Sanctuary of Antiochus I Theos of Commagene. https://allinnet.info/antiqui-ties/tomb-sanctuary-of-antiochus-itheos- of-commagene/

34 According to some researchers, among the heroes there are such gods/deities as Hercules-Vahagn, Zeus-Aramazd, Apollo-Mithra, Venus-Aphrodite- Astghik-Anahit, etc. The main god, the father of the family, Aramazd, is enthroned in the center.

35 Vahanyan V., Ghazaryan O. Transformation of plant and animal motives in Armenian Medieval (IX-XIV centuries) ornamental art. Monograph, “Astghik Gratun”, Yerevan, 2016, 256 p.

-

Prof. Vahanyan G*. Decoding Prehistoric Art: The Principles of Natural Philosophy on the Tablet of Shamash. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 3(5): 2022. OAJAA.MS.ID.000571.

-

Natural Philosophy, Greek Krater, day-light, Mythical creatures, Masculine, Spiritual principle, Armenian rock art

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.