Mini Review

Mini Review

The New Representations of Chinese Aesthetic: A Case Study of Four Chinese Fashion Brands

Viahsta Jiyue Yuan3, Magnum Man-lok Lam2*, Eric PH Li1 and Wing-sun Liu2

1Faculty of Management, University of British Columbia – Okanagan Campus, Canada

2Institute of Textiles and Clothing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

3Faculty of Management, University of British Columbia – Okanagan Campus, Canada

Magnum Man-lok Lam, Research Assistant Professor (Fashion Business), Room ST702, Core S, Institute of Textiles and Clothing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

Received Date: July 09, 2021; Published Date: July 21, 2021

Abstract

Fashion is widely recognized as a mirror of contemporary culture, as it not only reflects the socio-cultural conditions of the time but also shapes social preferences and lifestyle. Consequently, by determining the next lifestyle trends, fashion designers play a central role in this cultural production process. This paper focuses on four Chinese fashion designers and brands and their role in representing and reinterpreting Chinese culture through their collections. Our findings show that Chinese fashion designers have adapted various symbols from different subsets of Chinese heritage culture in their designs. At the same time, the contemporary Chinese fashion designers are taking an active role in recreating the representation and interpretation of Chinese culture through their design process. Through these four case studies, we identified four sources of aesthetic production and the mechanism of cultural production of Chinese aesthetic. Our study thus advances the current understanding on fashion and cultural heritage in the marketplace.

Keywords:Fashion design; Chinese design; Fashion branding; Cultural heritage; Case study; Aesthetics

Introduction

In the past few decades, Asian fashion designers have drawn tremendous attention from the global consumers [1]. Since the early 1980s, several Japanese designers, including Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, and Rei Kawakubo, have gained tremendous success in the Western fashion world by introducing oriental design elements and philosophies. However, rapid globalization has accelerated the cultural exchange and interpretation between the East and the West. Asian fashion designers, such as Uma Wang, Laura Kim, Chitose Abe, Huishan Zhang, and Shiatzy Chen, have brought influential designs that intertextualize Asian- Western aesthetic, knowledge, and craftsmanship, while bringing new ideas into the fashion industry [2].

The emergence of Asian fashion is partly driven by the rapidly growing economies in the region, with China, India, and South-east Asia creating new market opportunities for both international and local fashion designers [3]. Local manufacturers and designers are no longer solely responsible for producing low-end goods for the rest of the world but have rather become new competitors for well-established global brands by offering high quality and unique designs. China, in particular, is presently the world’s largest luxury market for fashion, jewelry, watches, and beauty products [4]. While the appetite for luxury international fashion brands continues to surge in a post-pandemic China [5], recent years have also witnessed a considerable increase in Chinese national pride, giving rise to a new fashion phenomenon in the country promoting China Chic (i.e., Guochao). Indeed, according to the available evidence, Chinese consumers are increasingly interested in patriotic consumption and are highly supportive of domestic fashion and home-grown designers, while abandoning foreign icons [6]. As a result, international fashion brands are struggling to regain customer trust and loyalty, prompting them to engage in a variety of strategies rooted in a better understanding of Chinese culture.

As the rise of Chinese fashion is still a mystery to many global brands, the identity of Asian fashion is polysemous. To capture a better understanding of the new representation of Asian designs, the aim of this paper is to elucidate how Chinese fashion designers incorporate their cultural heritage to establish their brands in the global and local markets. We argue that fashion is both a mirror and a determinant of the formation of contemporary consumer culture [7]. Guided by this premise, we examine how this new fashion representation of Chineseness offers symbolic resources for consumers to construct, or even upscale, their national identities. To accomplish this goal, we employed a case study method guided by aesthetic and fashion theories to analyze how fashion designers redefine and reconstruct “Chineseness” in the fashion industry. We argue that the culturally embedded fashion system enables consumers to understand the meanings and ideologies of the associated culture that aligns with the notions of transformation, hybridization, and localization presented in extant global consumer culture literature [8].

Literature Review

The Sociology of fashion

The conventional understanding of fashion is primarily concerned with the use-value of commodities for exchange and transaction. This economistic perspective focuses on the material (e.g., a piece of garment) and immaterial (e.g., design concepts and styling practices) aspects of fashion-clothing in satisfying the pragmatic, utilitarian functions such as body protection, comfort, camouflage, and so forth. From a Marxist perspective, the pursuit of fashion is regarded as a form of false consciousness where libidinal consumers chase after the trivial and the unreal in the capitalistic society [9]. In a similar vein, Veblen [10] perceived fashion as a wasteful social practice sustaining an illusion that one can uplift his/her social class through conspicuous consumption and by assimilating into the upper-class lifestyle.

The contemporary understanding of fashion has experienced a radical semantic turn largely shaped by the work of Baudrillard [11], according to whom all types of consumption carry a metaphysical value (i.e., sign-value) beyond use-value. Baudrillard has drawn attention to the ideological and symbolic aspect of fashion as inscribed in everyday consumer experiences. More recently, Godart [12] pointed out that “fashion is a total social fact and a phenomenon where most spheres of social life interact”, suggesting existence of an inextricable link between fashion and culture. As a form of wearable art, fashion apparel not only performs utilitarian function, but also helps satisfy normative social needs, including self-expression and identity construction [13], establishing social relationship [14], as well as communicating cultural affiliations and meanings embedded in the norms, values, and traditions associated with a particular socio-cultural context [15]. As distinct from mere apparel, fashion not only allows individuals to interpret their personal and social identities, but also serves as an ideological domain in providing consumers with diverse, or even countervailing, meanings in fashion discourses. It also enables consumers to forge and make sense of their identities, as well as enact the immediate interpersonal dynamics in their immediate social sphere [16].

The interpretation of countervailing fashion meanings is always influenced by various factors. Murray [17] argues that consumerperceived fashion meanings are developed from the broader sociocultural history and the current social spheres they engage in. From individual consumers’ perspective, fashion mediates the tensions created by cultural pluralism and complexity. Thus, from a design perspective, the historical cultural background and current sociocultural experience are hybridized and infused into a meaningful fashion style, thus becoming an expression of the designer self and defining designers’ creativity and positioning. Further, the transferal of cultural meanings can be shaped for symbolic purpose, whereby individuals share a similar fundamental socio-cultural context and incorporate their own values and beliefs in order to form a so-called cultural meaning transfer system [15]. Kawamura Y [18] suggested that fashion can be consumer-generated content as individuals utilize mass-produced fashion products as a resource to forge unique personas that reveal their perspectives, tastes, experiences, and values.

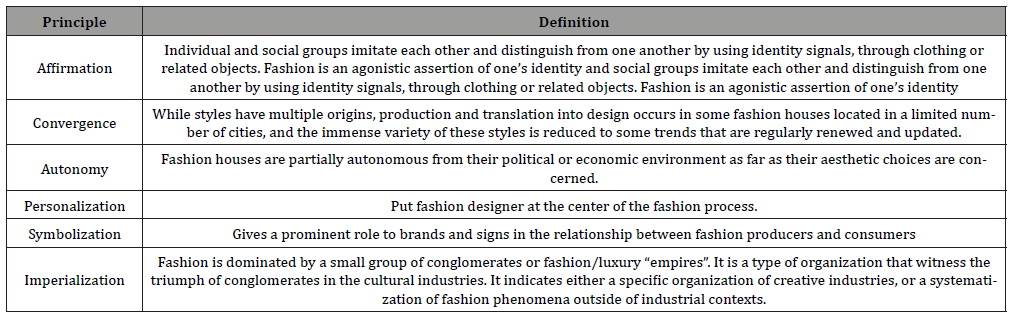

Table 1:Six Principles of Fashion [12].

The creation and diffusion of these countervailing meanings require active participation of individual consumers. However, fashion designers and other fashion “diffusion agents” such as mass media and consumer opinion leaders also play an essential role in the construction and diffusion of fashion meanings [19,20]. Godart [12] identified six principles of fashion meanings, namely affirmation, convergence, autonomy, personalization, symbolization, and imperialization (Table 1). Fashion producers and agents also serve as sources of cultural meanings, while consumers experience the plurality and complexity of consumer culture as a whole. They mediate diverse and sometimes opposing cultural contexts through the framing and production of relevant fashion meanings and transfer them to the consumers in a dialogical way. To better understand the impact of globalization and the growing interesting in designers’ creative process, the present study seeks to answer the research question: How do Chinese designers re-define and re-configure the “Chineseness” and “aesthetic DNA” in their designs? In this study, we examine four Chinese designer brands to understand the adoption and transferal of specific fashion meanings from fashion producers and agents’ perspectives (Table 1).

Transformation of fashion in Chinese society

The fashion industry experienced a series of transformation in the past century in the Chinese consumer society. Fashion styles in China have often reflected the socio-cultural context of various historical period. For instance, during the Cultural Revolution (mid-1960s to mid-1970s), the Chinese society experienced an anti-fashion sentiment. The sartorial code during that period was considered as “deadly fashion” dominated by three iconic styles, namely the Zhongshan zhuang (Mao suit), the qingnian zhuang (youth jacket), and the jun bianzhuang (casual army jacket) [21]. The emphasis on uniformity and unisex clothing reflected the prevailing political ideology that influenced by the former PRC President Mao’s desire to “sweep away” the past and allow a new China to emerge. The Mao suit was also associated with Lenin suit and had become a political statement [22]. In other words, the popularity of these public attires signified the need for conformity under the influence of the Communist Party ideologies.

Since the late 1970s, the new market socialist mechanism in mainland China not only opened up the Chinese markets to international brands and investors but also imported commodities, media, ideologies, and cultures that liberated the Chinese consumers and provided them with a wide variety of consumption choices. Fashion was embraced by Chinese consumers who appreciated the variety of style available to them. New fashion styles, usually influenced by the Western or Japanese consumer practices, were brought to the Chinese market together with other cultural commodities such as Hollywood movies, music, TV drama, arts, and manga/animation. Bell-bottom pants, xiaojie shan (Miss Shirt), Shenshi Xue (Gentleman Boots) as well as other oversized clothing styles became popular in the Chinese fashion market [21]. Since then, Western brands and fashion styles have become the dominant fashion images in the Chinese fashion market and mass media. Consequently, being fashionable is perceived as equivalent to being modern and affluent and has become an important social capital for emerging Chinese consumers. In response to this growing trend, luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Kenzo, Donna Karan, and Fendi have established their retail outlets in China. Luxury consumption in China began to thrive in the 2000s and Chinese economy has since become the second largest in the world [4]. The consequent rise of middle and upper-middle class as well as the growth in the number of “super-wealthy” Chinese citizens has created a promising market for luxury brands [23]. The desire for exclusivity and uniqueness has also opened up new market opportunities for local brands and designers. In addition to using Western brands to flaunt their wealth, affluent Chinese consumers have started to hire local fashion celebrity designers to customize their outfits. “Designed in China” is thus slowly becoming a strong identity marker for Chinese consumers [24].

The current Chinese fashion industry is experiencing the “renaissance” period as Chinese fashion designers are increasingly incorporating all aspects of everyday life in their collections, such as Chinese product design, characters and symbols, architecture, and other art forms, including calligraphy, painting, Beijing Opera, face drawing, shadow play, and so forth. Some designers are also exploring the heritage of regional cultures, ethnic minorities, and different generations, as well as Western fashion and arts. In sum, the Made in China concept is gradually being replaced by the Created in China label [25]. Many Chinese designers are reconnecting with ethnic communities in order to show the internal cultural diversity of the Chinese fashion system, as well as to acknowledge these original contributors to the so-called “Chinese aesthetics.” Well-established designers such as Wu Haiyan, Zhang Tianai, Zhang Zhaoda, and Chen Jiaqing, and fashion brands such as Red Phoenix (Beijing), Pu Jade (Beijing), Tong Ran (Guangzhou), Fish (Shenzhen), and Heaven (Shenzhen) have adapted ethnic themes in their collections [26]. Lindgren T [22] concluded that Chinese designers either strive to emulate roles like those in the Euro-centric fashion system or seek ways to reference the structures of the global fashion system with alternative aesthetic with significant global ramifications. In this process, the concept of “heritage” is generally defined as “the representation of the past” and is thus reconnected to a number of topics such as popular history and the construction of national or regional identity, as well as the development of tourism and consumption [27]. However, rather than being a fixed entity, heritage or history is widely understood an activity or an outcome of social construction [28]. Ashworth GJ, et al. [25] also pointed out that heritage is dissonant, as it is always held in tension between competing ideologies as well as between group and individual interests. Brett D [26] similarly argued that heritage is “a product of the process of modernization” as the re-articulation of the past and the differentiation of traditions or old and new reflects the forwardness of cultural development.

Case Study Method

In conducting this investigation, we employed a case study approach [29] as our goal was to understand the role of cultural heritage such as symbols and philosophies in the Chinese designers’ collections. Four Chinese fashion brands/designers—Shanghai Tang, Vivienne Tam, Qiu Hao, and JNBY—were chosen for this analysis, which primarily focused on comparing and contrasting different design themes, design features, and key symbols employed in their previous collections. When interpreting our findings, our aim was to elucidate how these design elements reflect Chinese culture and Chinese aesthetics in the fashion market.

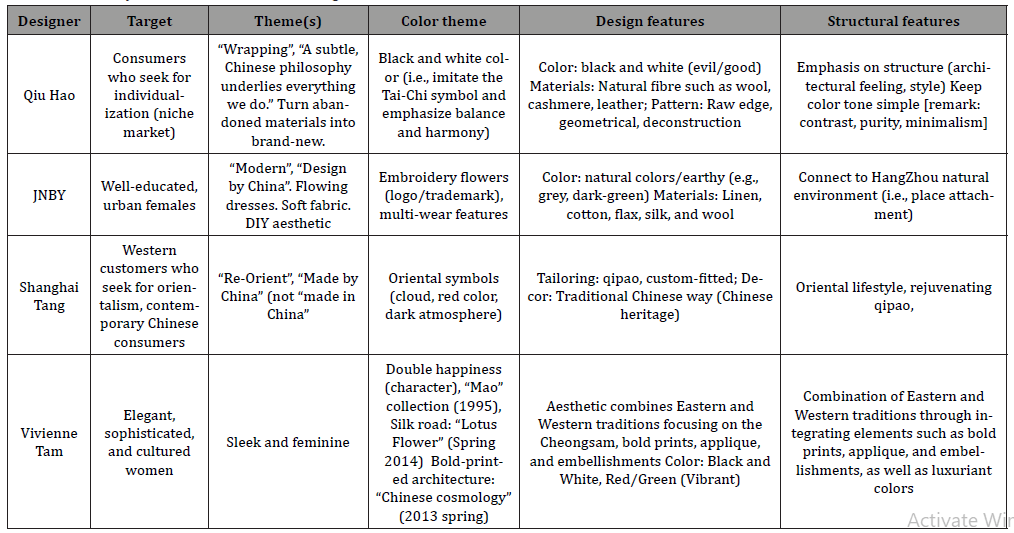

In addition to analyzing the aforementioned fashion designers’ collections and branding strategies, we also examined how “diffusion agents” [18] such as fashion journalists, editors, advertisers, and publicists portray the studied brands and collections to different audiences. During this process, we adopted the approach proposed by Marcus [30] to tracking the “flow” of the brands and designs. The data employed in these analyses is mainly sourced from archival records accessible through designers’ or brands’ official websites and fashion-specific media sources (e.g., print ads, media interviews with designers, editorials/commentaries) published between 2010 and 2014. As our investigation focused on determining how design concepts, brand meanings, and promotional messages circulate in the marketplace [31], we also conducted visual analysis to provide insight into the role of non-textual elements in the construction of Chinese aesthetic. By analyzing the origins and the changing design themes and vision, as well as by investigating different design features (such as the structural characteristics, visual patterns, color themes, material choice, fabrics, and finishing techniques), we seek to provide a holistic understanding of the inter-relationship of Chinese design and cultural heritage. A summary of the four case studies is provided in Table 2.

Table 2:Summary of Four Chinese fashion designers.

Subtlety of Chinese: Qiu Hao

Qiu Hao is a Chinese fashion designer who stared gaining global attention after receiving the Woolmark Prize at Paris Fashion Week in 2008. This was a great honor, given that the recipients of this prestigious prize include world-leading fashion designers such as Karl Lagerfeld, Donna Karan, and Giorgio Armani. Qiu was also named as one of the most important people in the Chinese fashion industry by Forbes magazine in 2010. In 2011, He was nominated for the Breakthrough Designer Award at the Global Fashion Awards held by WGSN, a London-based fashion trend forecasting editorial site. relying on vibrant colors and embroidery featuring dragons or flowers, Hao nonetheless successfully conveyed the “subtle Chinese philosophy” that underlies everything he does [33]. This approach to fashion design is exemplified by the woven leather skirt from his 2014 Spring-Summer collection, which was constructed by cutting leather into thin pieces using laser and folding them into a straw mat pattern. The skirt edge was left untreated to form a cowboy style fringe, but Hao used a special leather folding technique to ensure that the leather strips would not soften over time upon exposure to grease. The underlying theme of this collection was using discarded materials to create something new. Moreover, as raw edges and fringes made of leather can be easily damaged, Hao employed new techniques to avoid this unfavorable feature. In his 2014 Autumn−Winter collection, he continued with this theme, whereby he relied on wool shrinkage to create a soft, silky, and flowing look to emphasize the feminine side of his design.

Qiu once expressed that fashion designers often abandoned the old traditions when they are chasing after new techniques and materials. Qiu argued that fashion designers need to constantly adopt a new way of thinking in order to turn traditions into brandnew worldviews. With this underlying philosophy, Qui celebrates his inherited Chinese culture by giving it a brand-new representation without explicitly showing any elements or stereotypical symbols that signify China. However, every piece of his design still carries a strong sense of orientalism, allowing people who share similar backgrounds and beliefs with him to better understand his ideologies.

Crossing the boundaries: Vivienne Tam

As a Chinese fashion designer, Vivienne Tam is a pioneer in combining Chinese and Western aesthetics. She entered the Western fashion world in 1995 with her Mao collection and soon became one of the iconic Chinese fashion designers on the global stage. She is seen as radical, novel, and forward-thinking designer due to her use of political icons’ portraits in her design. She was named as one of the “World’s 50 Most Beautiful People” by People magazine and was listed as one of the “Top 25 Chinese Americans in Business” by Forbes [34].

Tam’s design strategically combines Eastern and Western traditions, integrating elements such as bold prints, applique, and embellishments, as well as luxuriant colors to create an unconventional aesthetic experience. This cultural clash and hybridity are a consistent theme in her collections. In her Spring 2015 ready-to-wear collection, models were clad in modern athletic outfits that were unconventionally decorated with magnificent Chinese-style floral embroidery and prints. The color tone of the fabric was deliberately simple and natural to allow vibrant and elegant embellishments to stand out. Such cultural hybridity was also evident in Tam’s 2014 FW collection during the Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week. Models wore tall leather boots, long A-line skirts, and fur accessories, but the entire look was highly sophisticated due to the delicate embellishments featuring lotus, origami-like lace and prints.

Tam frequently incorporates others’ design and creation into her collections. For example, when she printed Mao’s portraits across her fabrics, she subtly expressed her views on the political situation in China through echoing Andy Warhol’s artwork “[no title] From Mao Tse-Tung”. Tam’s adoption of Andy Warhol’s famous screen-printing techniques to re-create Chairman Mao’s portraits, on the one hand, aimed to illustrate the restrictions Mao’s regime imposed on people’s creativity and to show Mao as the only icon Chinese people were supposed to worship at the time. On the other hand, Tam was keen to tell the world that China was rapidly changing. The Mao’s portraits on her dresses were manipulated with a sense of humor, conveying her desire to make fun of this political leader in a provocative manner. At the same time, the different look of the portraits reflected her disagreement with Warhol, indicating that creativity and diversity are widely accepted in modern China, where people are now able to express their thoughts without being restrained by the government.

Besides arts, Tam also actively engages in bringing technology into the fashion world. In 2014, she collaborated with WeChat, one of the most popular social media platforms in China, to invite her fans to model in her fashion show or visit her backstage. She is also incorporating high-tech features into her designs, as exemplified by printing a QR code together with a pattern inspired by Chinese cave paintings on the back of an iPhone case.

Re-orientalization: Shanghai Tang

Shanghai Tang is a brand created in 1994 by the late Hong Kongbased entrepreneur David Tang in response to the global fashion trend of orientalism. He envisaged Shanghai Tang as the first luxury Chinese brand in the international market. By revitalizing the imagery of Shanghai at its peak of modernity and international trade in the 1900s, Shanghai Tang successfully targeted mainly Western consumers, including Princess Diana and Kate Moss. Although the company was hurt by the financial crisis in 1997 and sold a majority of its shares to Richemont group, its expansion did not cease.

As noted by Clark [35], the brand is successful in reviving traditional Chinese culture, as it is interpreting and expressing Chineseness visually, materially, spatially, and texturally. As its designs are inspired by 1930s Shanghai, the tailoring techniques are reminiscent of “The Imperial Tailor” who specialized in making custom-fitted cheongsam or qipao in order to echo the identity of traditional Chineseness. The design features also include red and gold color, traditional Chinese characters and symbols, prints, embroidery, and materials such as silk and wool, which usually give consumers a strong feeling of Imperial China. For the same purpose, a bamboo belt was used as an accessory in the 2013−2014 Fall and Winter as well as 2015 Summer collection [36]. The qipao collar and the Chinese-style button pan kou are also utilized in many of its collections. The brand also started incorporating more contemporary elements, while also focusing on the utilitarian function of clothing. For instance, a men’s sporty bomber jacket was shown as a part of Shanghai Tang’s 2015 Spring and Summer collection, and the women’s wear line was leaning towards contemporary urban style.

Shanghai Tang’s retail outlets are also carefully decorated with red or warm color tones to reflect its brand identity. The use of wooden or bamboo furniture, dark atmosphere, and oriental symbols such as clouds and the character “shou” further contribute to an Asian or Oriental aura [36]. In line with the retail stores that pay homage to Chinese culture, the fashion shows express strong orientalist ideology. From the decoration of the runway (using gold, red, and teal color reminiscent of the Imperial China) to the choice of models (exclusively Asian) and music (featuring traditional Chinese instruments such as Chinese plucked zither GuZheng and Bamboo Flute), every component is carefully selected to convey the Chineseness of the design. From the tailoring techniques to the fabrics it uses, as well as the fashion shows and architectural spaces in stores, Shanghai Tang consistently engages in rejuvenating Chinese heritage and culture by explicitly employing orientalist components, thus proudly making a statement for “made-by- Chinese” to the world [37].

Improvising contemporary Chinese: JNBY

In 2012, JNBY entered the global market by opening over 600 stores worldwide and holding its first fashion show during Tokyo Fashion Week in 2010. In 2019, the Chinese designer brand launched the men’s wear and kids’ wear brand, A Personal Note 73, to attract the fast-growing and fashion-forward consumers in China [36]. With its modern and conceptual designs and emphasis on product quality, JNBY makes Chinese designs appealing to the global fashion industry. For JNBY, Chineseness is not only conveyed through the use of red color, dragon patterns, or qipao. Instead, the brand employs materials and styles that are worn every day by the general public in order to create a nostalgic vibe. In contrast to Shanghai Tang or Qiu Hao’s masculine and structural design features, JNBY emphasizes the gentle and feminine imagery of a woman by focusing on loose-fitting clothes reminiscent of an army of soft-skinned Transformers [38].

JNBY is an acronym denoting “Just Naturally Be Yourself”— message that is embodied in the design and culture of the brand. The brand relies on simple and earthy color tones, natural materials such as linen, silk, cotton and wool, and the concept of convertible clothing. Its designs are associated with a simple but meaningful imagery. Unlike other modern fashion labels, JNBY focuses on quality, comfort, and utilitarian function of its apparel. Its masterful designs allow consumers to convert a single piece of cloth into different garments such as a top, a cardigan, a shawl, or even a blanket. Without striving to follow fashion trends, JNBY stays true to its own style, which usually involves soft and draping fabric, flowing dresses and small embroidered areas, which have become recognizable as the company’s trademark. Such meaningful and consistent design theme first emerged from a collective of 12 art and design students, including the brand’s founder Li Lin, all of whom originated from the City of Hangzhou. Their strong emotional attachment to the city is evident in all their collections. Hangzhou is always associated with a grayish color tone and a gentle, feminine imagery, due to the misty rainy weather, and the heritage constructions and quartzite roads the city has preserved. To capture this unique atmosphere, JNBY’s designs consistently employ earthy colors such as gray, taupe, and navy, as well as small but sophisticated embroideries.

JNBY’s designs usually feature patterns, cutting, embroidery, and fabrics that were used to make clothes for laborers and farmers, and generally people of lower social standing in China. For instance, in both 2014 SS and 2014/2015 FW collections, JNBY used the rugate fabric to create a nostalgic feeling, making the clothes look like they have been stored in the closet for many years and are now ready to be passed on to the next generation. Moreover, the application of scratches on the fabric as a kind of embellishment used in its 2014/2015 FW collection enhanced the association with the image of lower-class laborers, since they were usually exposed to tough working conditions where clothes can be easily damaged [38]. Although these designs remind people of low-class and low-income workers of the past, they satisfy consumers’ desire for differentiation in the market oversaturated by luxury. They also evoke consumers’ nostalgic feeling, as well as enhance the natureoriented concept, which differentiates the JNBY aesthetics from those of the other three brands discussed above.

Discussion

Our discussion summarizes our findings and addresses the key elements in this cultural production process. We show that the Chinese cultural heritage, as a source of identity, also inspires fashion designers to reinterpret their own culture in their design and brand production process. The design, as the material representation of designers’ interpretation of their own culture, not only becomes an identity of the designer/brand but also creates a new frame of reference for cultural and/or national identities of fashion consumers. The four Chinese designers presented here demonstrate how creative individuals can dynamically engage in the reconfiguration of Chinese aesthetics in the marketplace.

Sources of aesthetic production: design concepts and inspirations

Cultural heritage: Chinese culture provides a repertoire of symbols and narratives to inspire fashion designers’ creativity. For instance, designers are often inspired by the rituals (special events, celebrations, weddings, festivals), icons (royal/political figures) and language (e.g., double-happiness) that were used by both royal families and general public in ancient China. Designers are either inspired by the inherited traditions that have not been previously established within their internal knowledge system or are reminded by the cultures that are deeply-rooted in their memory. For example, Qiu Hao’s “Retiring from the World” collection featured key elements of the traditional costume of the Yi ethnic group in China [39]. As Yi ethnic culture was not a part of Hao’s personal experience, the designer chose to interpret it imaginatively. Vivienne Tam’s Spring 2015 ready-to-wear collection similarly incorporated the traditional Chinese paintings and symbols she had seen in the Forbidden City with cutting and materials used for modern athletic wear to visually reflect a cultural crash. In some cases, fashion designers inherit Chinese culture internally and present it in a manner that would only be appreciated by people who share a similar background. For example, JNBY’s Hang style (Hangpai) design consistently reveals a strong emotional attachment with the city of Hangzhou by emphasizing the feminine and grassroots features of the clothes. JNBY’s stores and fashion shows also aim to capture the city’s atmosphere. Since many of the brand’s designers have background related with Hangzhou, they are trying to convey their emotional attachment to the city and its perceived meanings to the consumers, mainly by evoking and strengthening people’s memory of the culture and stories associated with the place.

Aesthetic/fashion knowledge: Fashion designers often take references from other art forms [12]. Our findings show that Chinese designers also adopt other artistic works or cultural artefacts from other cultures in their collections. Vivienne Tam, for instance, employed Andy Warhol’s approach in her early Mao collection, which became an example of Western-inspired hybrid Chinese design. The integration of the Warhol’s unique color theme and printing style and the iconic Chinese political figure shows Tam’s courage in crossing the aesthetic and political boundaries. In fashion design, material knowledge is also an important source of inspiration, given that design development and the production methods in the fashion industry have changed very little since the early days, as “they remain largely manual and require extensive technical craftsmanship”. Fashion designers carefully choose the materials, color themes, silhouette, and other finishing (e.g., patterns, embroidery, prints) to communicate their ideas to fashion consumers as well as the general public. Fabric is key in fashion design and the selection of materials is crucial in reflecting the design concept as well as in conveying the culture of the design [40]. For instance, silk features frequently in Shanghai Tang’s designs as it symbolizes aesthetic refinement and purity in Asian cultures. The use of neoprene material also demonstrates Tam’s pioneering spirit and her preference for untraditional materials. JNBY’s use of natural fibers such as wool, silk, and linen represents the simplicity of agriculture-based way of life in ancient China. Similarly, Shanghai Tang and Qiu Hao heavily rely on traditional materials and symbols to convey their Chinese identity.

Individual experience: Designers’ individual experiences or insights are the other sources of internal knowledge that contribute to the construction of design elements. As discussed previously, inspiration could be drawn from new ideas that allow designers to convey a sense of novelty, or from embedded memory that will evoke their nostalgic feeling. The creation of the Shanghai Tang brand, for instance, has a very interesting story behind it. The name was inspired by one of the most popular TV series in the 1980s China, The Bund (Shanghai Tan/Shanghai Beach, HK-TVB), which told a story of Shanghai businessmen and spy during the peak of the city’s economic development in the 1920s. As soon as the TV series was released in Hong Kong, it became a big hit and its popularity rapidly spread across mainland China. The Shanghai Tang brand shares a similar background and design theme with the TV series, and the brand name is pronounced similarly as well. This deliberate reference to a popular TV show generates a nostalgic association, since consumers will be reminded of the positive emotions the TV series evoked when exposed to the Shanghai Tang brand.

Market demand: Although design is primarily an artistic endeavor, as it has a commercial purpose, its every aspect (elaboration, interpretation, and execution) is influenced by market demand. One of the ongoing phenomena around the world that influences the design process is the orientalization of both market demand and global fashion trends. The rise of Asian market and economy, China in particular, not only attracts more international brands to the marketplace, but also brings opportunities for the emergence, development, and expansion of domestic fashion brands. While Shanghai Tang decided to open the largest store in Shanghai in order to repatriate and capture the emerging Chinese market, Qiu Hao also claimed that he would like to expand organically in China rather than entering the international market. The use of WeChat during Vivienne Tam’s fashion show clearly demonstrates that fashion designers can express their creativity via the augmented services that are connected to Chinese fashion consumers. The rise of the Chinese influence in the global market also brings Chinese designs and its designers under the world spotlight. The emergence of young Chinese designers, such as Qiu Hao, Uma Wang, and Masha Ma, has turned China into a new fashion capital. As consumers are increasingly appreciating Chinese fashion designs, JNBY responded to this trend by expanding into the international market. This strategic move allows the brand to significantly improve its recognition and market share, while enhancing the customer-perceived value of its garments by marketing itself as an international fashion brand instead of a local business.

Identity and representation: The construction of Chinese aesthetic

In this section, we present a comprehensive analysis of the design process by examining how Chinese designers interpret, elaborate, and transform their design concepts via the actual design (materialization). For this purpose, we critically analyze the positioning strategies of the studied Chinese designers/brands in the global fashion marketplace. Hobsbawn EJ, et al. [41] introduced the concept of “invention of traditions” through the distinction of “spontaneous generation” and “invention”. In this study, we argue that Chinese fashion designers are key agents in “inventing” both “traditional” and “contemporary” Chinese aesthetic. The combination of cultural heritage (historical aesthetic) and modern design elements (“new Chinese”) indicates that the Chinese culture industry is experiencing a dynamic transition period.

Our findings show that Chinese aesthetic is a fluid construct. Chinese designers creatively re-interpret and re-present Chinese culture through their own creations. The Chinese designers are active in developing their brands in the fashion industry by redefining Chinese aesthetic in their own way. Having their “voices” and “identities” circulate within the fashion market is crucial for the new generation of Chinese designers. Vivienne Tam and Shanghai Tang are representing Chinese cultural heritage to non-Chinese consumers through their collections. In Vivienne Tam’s case, the mix of art, fashion, and politics has allowed her to successfully forge a unique identity in the global fashion industry. Moving from the controversial “Mao collection” (1995) to the latest “Obama collection” (2014), Tam has introduced her way of “East meets West” to the fashion world. On the other hand, Shanghai Tang employs re-orientalization strategies as the brand has changed the meanings and concepts of the word “double happiness.” Instead of focusing on the linguistic meaning of the Chinese character, “double happiness” is now recognized as a Chinese character and an icon that represents Chinese culture to the world audiences.

Qui Hao and JNBY have adopted a different strategy, whereby they are passing their understanding of Chinese philosophies to the new Chinese consumers by not using any iconic Chinese cultural symbols (e.g., red color, dragons, floral prints). Instead, these designers are striving to provoke a nostalgic feeling and the nature-oriented concepts through color and material choices. According to Godart FC [12], fashion is a process of imitation and distinction. Our findings show that Chinese designers are imitating past designs or clothing styles in their collections in order to convey the sense of continuity in the process of creating the “Designed in China” label. At the same time, they add new elements, either from their own lived experience, via reinterpretation of Chinese culture, or from the Western fashion world, to their repertoire to create a rich design element database for contemporary Chinese designers. Our findings show that Chinese identity and Chinese aesthetic are still being redefined and negotiated. Fashion designers or brands, together with local and international media, are co-defining the meanings of concepts such as “Chinese-ness”, “Chinese aesthetic”, and “Chinese design” in the fashion marketplace. In that sense, Chinese fashion designers are recreating Chinese heritage through ongoing design process, thus celebrating “the past in the present” [42].

Conclusion: Democratization of Fashion

In summary, our findings indicate that Chinese aesthetics, heritage, and representations are undergoing constant cultural reconstruction processes. Cultural heritage, in this sense, is no longer a fixed construct. It is a fluid construct [43] and is determined by designers’ selection, interpretation, and elaboration, as well as reinterpretation and circulation in the media [31].

Stevenson [44] points out an inseparable and mercurial nature of the terms “new” and “fashion.” The emerging Chinese fashion industry reflects the democratization of thinking in the contemporary Chinese society [45]. The rise of the creative class, or cultural creative [46], in China represents a new era of enlightenment, empowerment, and critical thinking. Creative space is being developed and reinforced under the new market socialist framework in the contemporary China context. Fashion, for instance, is not only a product or trend innovation process, but rather a dynamic process of identity seeking and negotiating, and production. As mentioned in the preceding sections, redefining “Made in China” label involves a continuous national identity searching, negotiating, and representing process. Fashion designers in the current context illustrate the freedom and empowerment in constructing the “Chinese design” in both local and global markets. Our findings also demonstrate that the design elements are not limited to well-recognized symbols but also designers’ own interpretation and elaboration of Chinese culture. The unlimited space for creativity also presents the political transformation of Chinese society. The Chinese fashion industry is at the intersection of socialism and capitalism, which opened up a new way of Chinese re-presentation in the global fashion industry. The multiplicity of “Chinese” representations also contradicts the uniform state-created Chinese image. Moreover, the diversity of cultural interpretation and elaboration represents the role of the new creative class in China. In summary, the democratization of fashion in China does not reflect the challenges to the ruling power or represent the weakened governmentality. In fact, the tolerance for and acceptance of multiplicity and diversity demonstrate the confidence of the current government and the country’s ability to meet global expectations.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu Z, Borgerson J, Schroeder J (2013) From Chinese brand culture to global brands: Insights from aesthetics, fashion, and history. Palgrave Macmillan: New York.

- Tatler Hong Kong (2020) 18 Asian fashion designers who are doing us proud.

- Sheth JN (2011) Impact of emerging markets on marketing: Rethinking existing perspectives and practices. Journal of Marketing 75(4): 166-182.

- Forbes (2020) China is headed to the world’s largest luxury market by 2025, but American brands may miss out.

- South China Morning Post (2021) Why China is leading the global rebound in luxury spending: More e-commerce, and a growing consumer appetite for shopping rather than experiences.

- Business of Fashion (2020) Patriotic consumers are changing the Chinese market: Here’s how.

- Tse T, Tsang LT (2018) Reconceptualising prosumption beyond the ‘cultural turn’: Passive fashion prosumption in Korea and China. Journal of Consumer Culture.

- Cayla J, Eckhardt GM (2008) Asian brands and the shaping of a transnational imagined community. Journal of Consumer Research 35(2): 216-230.

- Barnard M (2014) Fashion theory: An introduction. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Veblen T (1957) The theory of leisure class. Allen and Unwin, London, UK.

- Baudrillard J (1981) For a critique of the political economy of the sign, translated by Levin, C., Telos Press, St Louis, MO, USA.

- Godart FC (2012) Unveiling fashion: Business, culture, and identity in the most glamorous industry. INSEAD Business Press, New York, USA.

- Crane D (2000) Fashion and its social agendas: Class, gender, and identity in clothing. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Simmel G (1957) Fashion. American Journal of Sociology 62(6): 541-558.

- McCracken G (1986) Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research 13(1): 73-84.

- Thompson CJ, Haytko DL (1997) Speaking of fashion: Consumers' uses of fashion discourses and the appropriation of countervailing cultural meanings. Journal of Consumer Research 24(1): 15-42.

- Murray JB (2002) The politics of consumption: A re‐inquiry on Thompson and Haytko’s (1997) speaking of fashion. Journal of Consumer Research 29(3): 427-440.

- Kawamura Y (2005) Fashion-ology: An introduction to fashion studies. South-Western College Publishing, Oxford, New York, USA.

- Tse T (2015) An ethnographic study of glocal fashion communication in Hong Kong and greater China. International Journal of Fashion Studies 2(2): 245–266.

- Tse T (2016) Consistent inconsistency in fashion magazines: The socialization of fashionability in Hong Kong. The Journal of Business Anthropology 5(1): 154–179.

- Wu J (2009) Chinese fashion: From Mao to now. Berg, Oxford, New York, USA.

- Lindgren T (2013) Chinese fashion designers in Shanghai: A New Perspective. In Heaton S (edt), Fashioning identities: Cultures of exchange, Inter-Disciplinary Press, Oxford, UK.

- Khan O (2015) Luxury consumption moves East. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 19(4): 347-359.

- Ferrero-Regis T, Lindgren T (2015) Branding ‘created in China’: The rise of Chinese fashion designers. Fashion Practices 4 (1): 71-94.

- Ashworth GJ, Graham BJ (2005) Sense of place: Senses of time, Ashgate, Aldershot.

- Li Y (2008) A study on the application elements of ethnic dress in modern fashion design. Cross-Cultural Communication 4(3): 23-26.

- Brett D (1996) The construction of heritage. Cork University Press, Cork, Ireland.

- Prats L (2009) Heritage according to scale. In Heritage and identity: Engagement and demission in the contemporary world; Anico M, Peralta E (edts), Routledge, London, New York, USA.

- Yin RK (1994) Case study research: Design and methods (2nd edn), Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- JNBY (2015) News.

- du Gay P, Hall S, Janes L, Mackay H, Negus, K (1997) Doing cultural studies: The story of the Sony Walkman. Sage, London, UK.

- JustLuxe (2012) Fashion designer Qiu Hao debuts Serpens collection.

- Business of Fashion (2008) Qiu Hao and Helen Lee: Diversity in design, comrades in commerce.

- com (2014) The history of Hong Kong fashion: A look back at 60 years of Hong Kong’s style evolution.

- Clark H (2012) Chinese fashion designers: Questions of ethnicity and place in the twenty-first century. Fashion Practice 4(1): 41-56.

- Jing Daily (2013) Shanghai Tang: The Definitive Chinese Luxury Brand?

- WWD (2019) China’s JNBY introduces brand with Andrea Pompilio.

- The New York Times (2010) Shape shifters that mutate with you.

- Harrell S (2012) Studies on ethnic groups in China: Ways of being ethnic in Southwest China. University of Washington Press, Vancouver, BC, USA.

- Jarman N (1998) Material of culture, fabric of identity. In Material cultures: Why some things matter; Miller D (ed.), Chicago University Press, Chicago, USA.

- Hobsbawn EJ, Ranger, TO (1983) The invention of tradition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Cambridgeshire, New York, usa.

- Butler B (2006) Heritage and the present past. In The handbook of material culture; Tilley C, Keuchler S, Rowlands M (edts.), Sage Publications, London, UK.

- Bauman Z (2000) Liquid modernity, Polity, Cambridge, UK.

- Stevenson NJ (2011) The chronology of fashion: From empire dress to ethical design. A&C Black Publishers, London, UK.

- Von Hippel E (2006) Democratizing innovation, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Ray PH, Anderson SR (2000) The cultural creatives: How 50 million people are changing the world, Three Rivers Press, New York, USA.

-

Viahsta Jiyue Yuan, Magnum Man-lok Lam, Eric PH Li, Wing-sun Liu. The New Representations of Chinese Aesthetic: Case Study of Four Chinese Fashion Brands. 8(5): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000698.

-

Fashion, Environment, Supercritical fluid, Microbial dyes, Sustainable

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.