Research Article

Research Article

Reimagining the Luxury Department Store: Investigating the Millennial Luxury Consumer and the Luxury Department Store from a Systems Perspective

Kelcie Slaton and Linda S Niehm*

Department of Apparel, Events, and Hospitality Management, Iowa State University, USA

Linda S Niehm, Department of Apparel, Events, and Hospitality Management, Iowa State University, USA.

Received Date: February 10, 2020; Published Date: February 21, 2020

Abstract

Observed shifts in consumer behavior have created disruptions and comprehensive change in retailing processes as a whole. The most dramatic change in consumer shopping behavior lies within the Millennial cohort. As a result, luxury department stores have struggled to find relevancy with these younger consumers. Millennials seemingly have an increased desire for luxury, items yet hold negative attitudes towards luxury department stores. Currently, no literature addresses Millennial luxury consumers, their connection with disruptions in the retailing industry, and particularly in regard to the luxury department store. Therefore, the authors propose a model to investigate the Millennial luxury consumer and the luxury department store based on systems theory. The proposed model will be used to understand the interactions and interdependence between the Millennial consumer, the fashion retailing industry, and specifically the luxury department store, from a holistic systems perspective. Additionally, the model can be valuable to the luxury department store retailer as it will provide support for strategic adaptations to ensure consumer attainment and business sustainability.

Keywords: Luxury Retailing; Millennial Consumer; Luxury Department Stores; General Systems Theory; Business Sustainability

Introduction

While emerging consumer and technology trends have been positive for online retailers (e.g. the Amazon effect), discounters, and fast-fashion retailers, other retail formats have been significantly challenged. Department stores, for example, have struggled to maintain relevancy in a changing environment, leading to store closures and downsizing [1]. Past industry wide practices encouraged retailers to hold large store portfolios, and growth was achieved through the expansion of selling space. While major department stores have experienced downturns, closures, and condensation, luxury department stores have also had their share of woes.

Traditional department stores typically stock many varieties of goods in different divisions or departments. While luxury department stores are similar in format, they distribute clothing, accessories and other lifestyle products which are exclusively designed and/or manufactured by/ or for the retailer, perceived to be of a superior design, quality and craftsmanship, priced significantly higher than the market norm, and sold within prestigious retail settings [2]. Luxury department stores, such as Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue, have recently experienced revenue declines in their full-line brick and mortar stores [3]. Marzilli et al. [4] suggest potential contributors to this decline include limited customer and transaction growth, growing competition, and growth of omni-channel strategies.

While industry and macro-environmental disruptions have stimulated comprehensive change in retailing processes, there has been a simultaneous observed shift in consumer behavior. The most dramatic change in consumer shopping behavior lies within the Millennials (born 1980-2000), the largest and most influential generational cohort to date [5]. Millennial consumers are motivated by social shopping, personal gratification, and unique products; they expect experiences, personalization, and integrated technology from the retailers they patronize [5]. Currently, there are 80 million Millennials in the US. The Millennial cohort spends an estimated $600 billion each year on retail purchases. This amount is projected to grow to $1.4 trillion by 2020, reflecting 30 percent of total retail sales. Thus, Millennials will have major purchasing power and impact on the economy for many years to come, making them a highly important customer segment for retailers [6].

Consumers have generally demonstrated an increasing desire for luxury products and services [7]. Specifically, demand for luxury products in the US is up 16 points since 2015. Further, Millennial consumers have shown an increased desire for luxury items and are buying these items at a much younger age. This cohort is brand conscience and willing to invest in luxury products [8]. However, Millennial consumers tend to have a negative attitude towards luxury department stores [4], despite their expressed preferences for luxury goods sold by these retailers. Therefore, identifying new sources of competitive advantage is critical for the luxury department store’s sustainability. Creating product, brand, and store differentiation, together with attainment of loyal target consumer groups like Millennials, are key strategic suggestions for the sustainability of luxury department stores [9]. No existing literature addresses Millennial luxury consumers, their connection with disruptions in the retailing industry, and competitive challenges faced by the luxury department store. Therefore, the authors propose a model to investigate the interactions and interdependencies between Millennial luxury consumers and the luxury department store from a systems theory perspective.

Background

Evolution of retailing

Retailing is defined as the “set of activities that markets products or services to consumers for their own or personal household use. It does this by organizing their availability on a fairly large scale and supplying them to consumers on a relatively small scale” [10]. This paper focuses on fashion retailing, or retailing that involves selling clothing, apparel, and related accessories to consumers [11]. Retailing as an industry is vital to most nations’ economies and has a strong influence on the consumer. The earliest forms of retailing date back to simple markets and basic operations where traders would sell goods to local consumers [12]. Trading grew so quickly that permanent stores were developed in markets close to many consumers bringing the need for skilled craftsmen in clothing and footwear [13]. In the 1800s, the general store was established selling a broad range of merchandise, but then was transformed into specialty stores selling a more specialized assortment [13]. The twentieth century brought forth the concept of the department store, which was clothing-based, but evolved into varied merchandise as the store format became more popular [14].

The evolution of retailing has been notable and rapid over the last 50 years as the balance of power has shifted from manufacturers, to retailers, and more recently to consumers. Additionally, as retailers were initially establishments where consumers could simply buy goods, they are now powerful entities and heavily involved in the marketing of their business and proprietary brands [15]. Recently, fashion retailers have faced shorter product life cycles and rapid technological transformations across the industry [15]. Consumers of all ages and social groups are enthusiastic about adopting these new forms of retailing (i.e., online and mobile), and as a result, clothing has become the fastest growing online category [15]. The rise of online shopping has negatively impacted the number of brick and mortar retail locations and increased the demand for additional channels such as online and mobile. In fact, most retailers today operate in multiple channels out of necessity. Increasingly retailers are moving towards a seamless, omni-channel business platform which integrates the different ways of buying merchandise and interactions between consumers and retailers [15].

The combined forces of change in consumer behavior, online shopping, and related technology have disrupted the fashion retailing industry and spurred subsequent trends [16]. According to Amed I, et al. [16], major retailing disruptions include digitization across the value chain, acceleration of industry pace, brands experimenting with direct-to-consumer, new innovated models, brick and mortar traffic decline leading to reinvent the store, and proliferation of data. Further, these disruptions drive trends in the fashion retailing industry, including the introduction of artificial intelligence, environmental sustainability, the rise of off-price, and a start-up mindset for retailers. Consumers of all ages and social groups are enthusiastic about adopting these new forms of retailing, and as a result, clothing has become the fastest growing online category [15]. While these changes have been positive for online retailers, discounters, and fast-fashion retailers such as Zara, they have been troublesome for fashion retailers, such as department stores, who have struggled to maintain relevancy [1].

Based on Census data, in 1999 department stores reported total annual sales of $230 billion but has declined since as 2016 reported total annual sales of $155.5 billion [17]. Additionally, these disruptions have resulted in many store closings; more than 3,800 retail stores in 2018 [18]. According to Percy [19], a new model for the department store is needed to ensure future success. Baird [20] concurs with the need for a new model, suggesting that the value provided by the concept store-within-a-store has been eroded by growth in online shopping.

While major department stores have experienced struggles due to industry and consumer change, luxury department stores have also experienced a downturn in their business [17]. Luxury department stores, such as Neiman Marcus, have experienced a decline in sales [3]and purchase consideration by consumers for luxury department stores has also dropped [4]. According to Dennis [3], reasons for the decline in luxury department stores include not only the noted major industry disruptions, but also the strong dollar’s impact on foreign tourism, a weak oil market, and competition. Demographic shifts demonstrated by Millennial consumers, who favor experiences and are motivated by online capabilities, have also presented challenges for luxury department store retailers.

Luxury department stores

According to Lindsey [2], luxury brands traditionally needed to sell their products in a luxury department store to signal that they had “made it” and were able to be successful. Examples of luxury department stores include Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, Barneys New York, and Bergdorf Goodman. These luxury department stores attracted a large amount of foot traffic as they held a large amount of inventory and helped introduce brands to consumers. Interestingly, there has been a decline in the overall luxury department store segment, yet an observed increase in growth of the luxury market by 32 percent, over the last decade [22]. To meet this market demand, luxury brands are looking for new distribution opportunities online and expanding their own branded retail stores [21]. There is a decided shortage of research on luxury department store retailing and virtually no existing literature on how the luxury department store may strategically address the changing consumer and competitive environment.

Millennial consumers

According to Giovannini, Xu, and Thomas [22], the luxury market in the United States is growing. The growth can be attributed to the emergence of a new luxury [23]. These “newcomers” do not fall into the wealthy segment that defined traditional luxury consumers but are purchasing luxury products at a younger age [24] and spending about $300 on each purchase [25]. While luxury marketers are still interested in the affluent Baby Boomer generation, this group is aging, and a larger, more powerful newcomer consumer cohort, the Millennials, is becoming strategically important [26]. The Millennial generation is comprised of consumers born between 1980 and 2000. Currently, there are 80 million Millennial individuals in the US, and they spend an estimated $600 billion each year on consumer goods, which will grow to $1.4 trillion by 2020. This will represent 30 percent of total retail sales in 2020. Thus, Millennials will have major purchasing power and impact on the economy; a segment retailer will need to capture for future success [5].

Despite the fact that Millennial consumers are young and just entering the workforce with lower earnings, they are brand conscience and willing to invest in luxury products [8,27]. According to Pitta [28], Millennials are digitally savvy which helps this generation inform how they think, what they like, and how they want products and services. Further, social media is a considered definitional to Millennials [28]. According to Kilian, Hennigs, and Langner [29], Millennials participation in and identification with social media is generally high and they use social media considerably different from other generations. Additionally, Millennial consumers want products now, they want to them to be perfectly tuned to their preferences, want to obtain them in the most convenient ways, and they want information from trusted individuals. Further, Millennials are attracted to brands that provide them with a desirable experience as it provides value and attracts them on an emotional level [30]. This observation is supported by research of Pine and Gilmore [31], who describe in their treatise on the “Experience Economy” that consumer preferences are moving from communities, goods, and services to experiences.

Millennial consumers are also categorized as having high levels a materialism, brand-signaling importance [32], and status consumption [33]. Additionally, this generation of consumers exude high levels of self-monitoring, low levels of dispositional guilt, high levels empathic concern [32], high levels of self-esteem [34], and high public self-consciousness who tend to make purchase decisions based on the influence and opinion of their peers [35]. Millennial consumers, while brand conscious [32] are less loyal than other generations and tend to purchase a wide range of merchandise at various prices [36]. For retailers to effectively reach the Millennial consumers, they need to speak the same language, reach them wherever they are, use the communication they use such as social media, and understand the complex combination of experiences and preferences that define them [28].

While there is ample literature on Baby Boomer consumers and luxury consumption, there is little involving Millennial consumers, especially in the context of the luxury department store. As previously noted, Millennial consumers hold starkly different attitudes towards luxury department stores [4]. As the retail industry is projected to see ongoing and unprecedented change, such as the increase in desire for luxury, increase of distribution channels, and the socio demographic characteristics of the luxury consumers and their behaviors [37,38,27,39]. Thus, the need for more in-depth studies concerning Millennial consumer behavior and luxury retailing.

Proposed Conceptual Model

The goal of this conceptual paper is to propose a new model to examine the interactions and interdependencies of the Millennial luxury consumer and the luxury department store, within the context of the evolving retail environment. Therefore, the authors drew from von Bertalanffy’s [40], general systems theory to propose an explanatory model. According to von Bertalanffy [41], general systems theory views systems and sub-systems as a set of interrelated and interdependent parts. A system may be defined as “a set of elements standing in interrelation among themselves and with the environment” [40]. General systems theory is well suited to understand the complex interdependent relationship in the areas of natural and social sciences, including retailing and consumer behavior. Further, the theory explains that everything within a system, and its small sub-systems, should work together for successful system outputs. Additionally, the goal of general systems theory is to describe and explain how organizations work and define multiple ways to accomplish various goals [41]. While other theories use linear thinking, von Bertalanffy’s [41] general systems theory recognizes that the interconnections of entities rather than a singular view and cause and effect relationships. According to Prokhorov [42], a need for an approach like this is important especially for business as economic changes cannot be predicted by traditional linear models. By utilizing this theory and looking at a system(s) and its processes as independent and intertwined rather than separate, it is possible to shed light on how businesses can learn, grow, and sustain themselves [43].

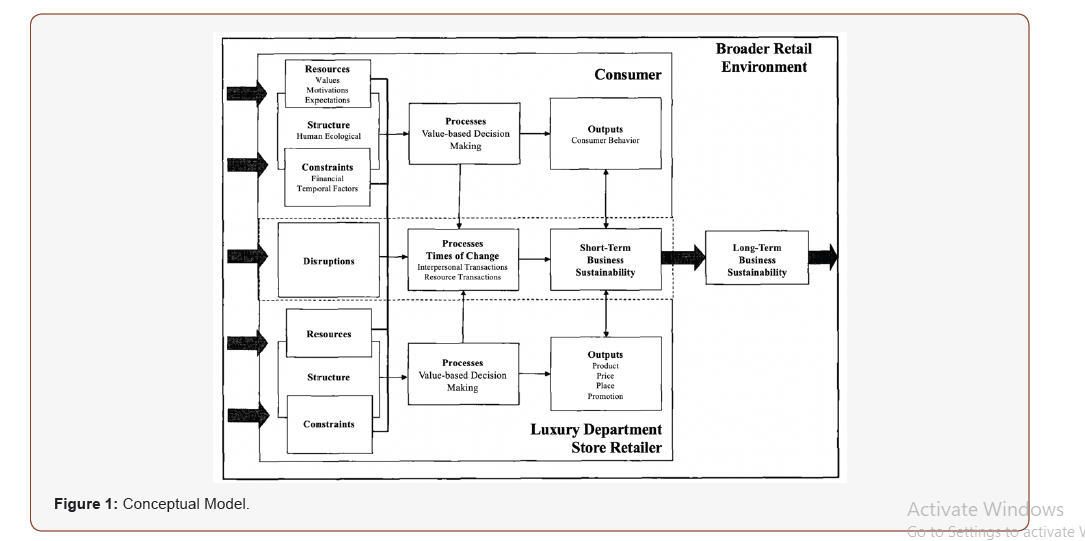

According to general systems theory, a system is organized by inputs, throughputs or processes, and outputs [41]. Inputs are resources and information that is needed to supply the system. Hobfoll [44], explains that resources can be categorized as objects, characteristics, conditions or energies that are valued as they contribute to the valued output of the system. Constraints are those elements that are potentially threatening to the system and may contribute to an actual loss [44]. Werbal and Danes [45], note that system structure overlaps resources and constraints as it is thought to encompass both. General systems theory explains that systems have different processes (decision-making, conflict management, problem solving) during times of both stability and change [45]. Additionally, processes are activities within a system that facilitate getting work done [41]. Finally, according to von Bertalanffy [41], outputs are outcomes, products, and services, created and delivered by the organization (Figure 1).

Drawing from general systems theory [41] will allow for a holistic understanding of the interactions and interdependencies of the Millennial luxury consumer, luxury retail department stores, and their operational environment. Using a systems perspective to understand luxury retailer and consumer relationships is unique to the literature. The proposed conceptual model will advance the fashion retailing literature and provide competitive insight to aid in sustaining the luxury department store’s business. This holistic approach is particularly important and timely give the magnitude of unprecedented change being experienced by contemporary retailers, especially department stores.

Future Research and Implications

Future research will allow for refinement and testing of the proposed model. First, a thorough review of luxury department store case studies and qualitative interviews will determine the variables and relationships to be specified within the model. Second, the model will be tested quantitatively with a survey of consumers and industry executives.

The paper makes a contribution to not only the luxury department store and consumer behavior literature, but also provides strategic guidance for fashion luxury retailers coping with the impacts of unprecedented retail change. Specifically, this model holistically will be used to understand the dynamic Millennial consumer, the fashion retailing industry, and specifically the luxury department store, from an all-inclusive systems perspective. The proposed model will provide valuable information on Millennial consumers whose spending power is set to rise to 1.4 trillion by 2020 and will represent 30% of the consumer population. This information will include their target customer profile, shopping and product preferences, and customer expectations that all retailers will need to understand to drive satisfaction, continued patronage, and their bottom line.

The conceptual model has both academic and industry implications. From an academic perspective, a new model, such as the one proposed, can be utilized in future retailing study to gain a better understanding of the retailer and the consumer in many different contexts. Specifically, academicians will be able to conduct further research on this phenomenon, using the proposed model, and increasing the available literature. Additionally, this information will provide valuable additions to course curricula that will enable students to learn more about the changing industry and obtain skills that will be desirable and useful when they enter the workforce.

Ultimately, testing the proposed model will take into account the changes within the industry and the changing consumer preferences and provide valuable information that the luxury department store practitioner will need to sustain the luxury department store. This information is valuable to the luxury department practitioner as it will provide support for strategic adaptations to ensure consumer attainment and business sustainability. These adaptations may lead to a new store model that will increase foot traffic of the dynamic Millennial consumer group and aid the luxury department store in overcoming challenges experienced in the evolving retail marketplace.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Kapferer JN, Bastien V (2009) The specificity of luxury management: Turning marketing upside down. Journal of Brand Management 16: 311-322.

- Lindsey K (2015) Why the relationship between department stores and luxury brands is changing. Deep Dive.

- Jay E (2012) New breed of consumer shakes up luxury fashion. Mobile Marketer.

- Blázquez M (2014) Fashion shopping in multichannel retail: The role of technology in enhancing the customer experience. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 18(4): 97-116.

- Eastman JK, Liu J (2012) The impact of generational cohorts on status consumption: an exploratory look at generational cohort and demographics on status consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29(2): 93-102.

- Prokhorov AB (2001) Nonlinear dynamics and chaos theory in economics: A historical perspective. Quantile 4: 79-92.

- Silverstein MJ, Fiske N (2003) Trading up: The new American luxury. New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin Group.

- Fernandez PR (2009) Impact of branding on Gen Y’s choice of clothing. Journal of the South East Asia Research 1(1): 79-95.

- Peterson H (2018) More than 3,800 stores will close in 2018-here’s the full list. Business Insider.

- Donnelly C, Scaff R (2013) Who are the millennial shoppers? And what do they really want? Accenture.

- Logan G (2008) Anatomy of a gen y-er. Personnel Today: 24-25.

- Fourrier FH (2017) World luxury tracking. Do you speak luxury? Consumer new luxury culture. Ipsos.

- Werbal JD, Danes SM (2010) Work family conflict in new business ventures: The moderating effect of spousal commitment to the new business venture. Journal of Small Business Management 48(3): 421-440.

- Loroz PS, Helgeson JG (2013) Boomers and their babies: an exploratory study comparing psychological profiles and advertising appeal effectiveness across two generations. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 21(3): 289-306.

- Marzilli T, Harris JL (2017) Despite challenges for luxury department stores, opportunity still exists among rich Millennials. Forbes.

- Townsend M, Surane J, Orr E, Cannon C (2017) America’s ‘retail apocalypse’ is really just beginning. Bloomberg, New York, USA.

- Grotts AS, Johnson TW (2012) Millennial consumers’ status consumption of handbags. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 17(3): 280-293.

- Percy I (2015) What’s killing department stores? Forbes.

- Fromm J (2017) How brands can win with Millennials in the experience economy. Forbes.

- Little K (2012) Young and fashionable: Gen y flocks to online luxury. CNBC.

- Stein J, Sanburn J (2013) The new greatest generation. Time International (Atlantic edtn) 181(19): 26-33.

- Samli A (1989) Retail marketing strategy: Planning, implementation, and control. Greenwood Press, New York, USA.

- Pitta D (2012) The challenges and opportunities of marketing to Millennials. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29(2).

- Dennis S (2017) Luxury retail hits the wall. Forbes.

- Baird N (2018) A cautious future for department stores in 2018. Forbes.

- Garton J, Fromm C (2013) Marketing to Millennials: Reach the largest and most influential generation of consumers ever. American Management Association, New York, NY, USA.

- Sun J, Wu S, Yang K (2018) An ecosystemic framework for business sustainability. Business Horizons 61(1): 59-71.

- Moore CM, Doherty AM (2007) The international flagship stores of luxury fashion retailers, in Hines T, Bruce M (Edts), Butterworth Heinemann, London: Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues.

- Lewis BR, Hawksley A (1990) Gaining a competitive advantage in fashion retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 18(4).

- Kilian T, Hennigs N, Langner S (2012) Do Millennials read books or blogs? Introducing a media usage typology of the internet generation. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29(2): 114-125.

- Pine JB, Gilmore JH (1999) The experience economy: Work is theatre and every business a stage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, USA.

- Panteva N (2011) Luxury spending drives recovery. Ibis World.

- Bertalanffy LV (1972) The history and status of general systems theory. The Academy of Management Journal 15(4): 407-426.

- Hobfoll SE (1989) Conservation of resources. American Psychologist 44(3): 513-524.

- Okonkwo U (2007) Luxury fashion branding: trends, tactics, techniques. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Newman A, Cullen P (2002) Retailing: Environment & operations. EMEA, Andover: Cengage Learning.

- Wahba P (2017) Can the American department store survive? Forbes.

- Amed I, Berg A (2017) The state of fashion. Business of Fashion: McKinsey & Company, USA.

- Jackson T (2011) Luxury consumer snapshot: Newcomers. WGSN.

- Tse KK (1985) Marks & Spencer: Anatomy of Britain’s most efficiently managed company. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK.

- Bertalanffy LV (1968) General System Theory. Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller: New York, USA.

- Vickers JS, Renand F (2003) The marketing of luxury goods: An exploratory study- three conceptual dimension. The Marketing Review 3(4): 459- 478.

- Kent T, Omar O (2003) Retailing. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, UK.

- (2018) What is fashion retailing. IGI Global Disseminator of Knowledge.

- Giovannini S, Xu Y, Thomas J (2015) Luxury fashion consumption and Generation Y consumers: Self, brand consciousness, and consumption motivations. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 9(1): 22-40.

-

Niehm LS, Slaton K. Reimagining the Luxury Department Store: Investigating the Millennial Luxury Consumer and the Luxury Department Store from a Systems Perspective. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 4(5): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000600.

-

Luxury retailing, Millennial consumer, Luxury department stores, General systems theory, Business sustainability

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.