Review Article

Review Article

Now and Then: The Fascinating Narrative of Fashion and Clothing Advertisements

Damayanthie Eluwawalage, Assistant professor, department of human ecology, Delaware State University, USA.

Received Date: June 29, 2019; Published Date: July 05, 2019

Introduction

This paper explores the nature of the texts and images associated with advertising throughout the histories, including commercial images, artistic and literary representations, photographs and postcards, the printed word and the visual arts in the fashion and clothing context (Figure 1).

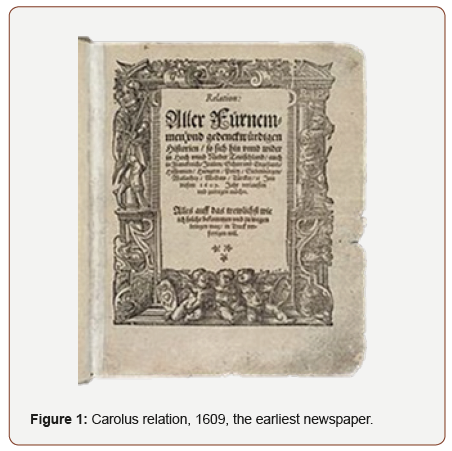

The term newspaper became popular sine the 17th century. Publications that we would consider to be newspaper publications today were appearing as early as the 16th century in Germany [1]. The Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien, printed from 1605 onwards by Johann Carolus in Strasbourg in German language, is regarded as the first printed, dated, appeared at regular and frequent publication intervals newspaper [2].

On 7 November 1665, The London Gazette (at first called The Oxford Gazette) began publication. It is considered to be the newspaper that decisively changed the look of English news printing. In 1731, The Gentleman’s Magazine, the first English language magazine published in London (Figure 2).

The exciting and fascinating narrative of the world press requires clarification as Raymond in his study of the Invention of the Newspapers explained, the initial appearance of newsbooks on 29 November 1641, caused the invention of the newspaper as we know it today. The first notebooks had title-pages and later developed the usage of section headings to indicate the date, and place of origin of letters [3,4]. Through the second half of the seventeenth century, c1665, the newspaper emerged and evolved. In the United Kingdom between 1830-1855, four hundred and fifteen newspapers were published. Between 1855-1861 about four hundred and ninety-two newspapers were published [5]. The power of the press in the nineteenth century and its capability and effectiveness to influence and govern certain aspects of social life is accepted and acceded to by many historians and writers, such as Raymond, Jones, and Cranfield. The contents of these newspapers were extensive. Subject matter including English culture, religious observances, popular amusement, leisure, education and law and crime were regularly depicted.

Review

Newspaper is one of the compensating forces of modern life, helping to draw us all together, tend to make us better, it is helpful, softening humanizing Christian influence, wrote Rev. Brook Herford in 1866 [6]. As Cranfield analyses, the narrative of the press is based on three main themes: intelligence, instruction and entertainment. All have meant different things to different people at different times [7]. Initially, the deficiency of literacy, especially amongst the inferior classes, justified the newspapers as a privileged and prestigious novelty to the elevated classes. As Cranfield described, more and more numbers of the working class were able to read. The appearance of the English (British) newspapers were transformed and adapted according to their novel audience [8].

The press has been, for the most part, the instrument of kings, priests, aristocrats, and imbeciles in carrying out their irrational, ambitious, uncivilized and uncivilising designs. - The Compositors Chronicle, 1842 [9]. For much of the nineteenth century, newspapers remained under the control and surveillance of governments. Nevertheless, the image of the newspaper as a harbinger, or indeed the active agent, of change, exerted a powerful hold over the contemporary imagination [10].

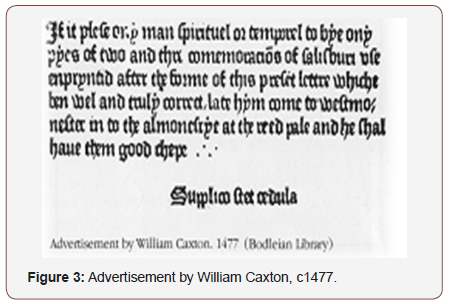

The Victorian advertisement exposes materialistic fantasies. It tells of goods that excited the imagination and of mundane realities of everyday life [11]. Advertising has had a long and vivid history. One of the earliest actual evidences of advertising is an inscription in the form of propaganda found on a 3000BC Egyptian tomb. There were signs customarily hang outside tailors’ shops in the Medieval era (Figure 3).

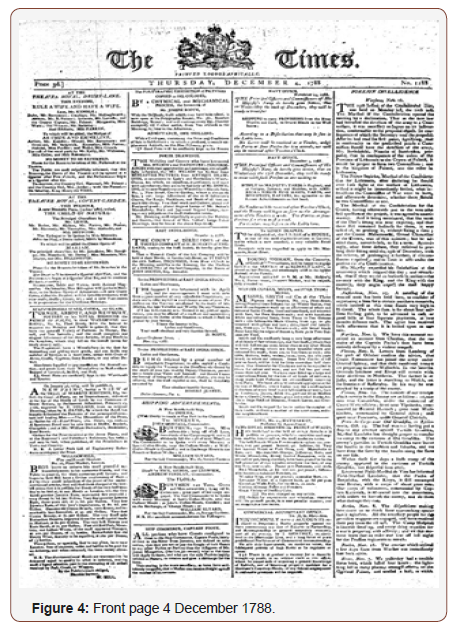

The history was made in 1477 when William Caxton pulled from his hand press the first ad to be printed in the English language. In time, tradesmen such as tailors were ordering printed announcements in the form of bills or cards for exhibition purposes or to handout to the passerby. At first, these ads were straight type designs, later becoming fancier, with Roman script and flowing characters. In 1788, ‘The Times’ published two shipping advertisements, each illustrated with a small line drawing, the first ever illustrated ads.

The illustrations for printed ads had to be rendered in line and reproduced by means of a hand-carved woodblock or metal engraving. The power press, invented in 1818, had replaced the hand operated press.

Advertising could be defined as a means of giving information about goods and services [12]. Of all the classes of media available, the press is regarded as the most potent means of persuasion. Modern newspapers are ranked among the most important means of opinion formation [13]. Magazine and newspaper advertisements developed into inevitable paraphernalia of the ever mutating nineteenth century. Advertising benefited both consumers/readers as well as the publishing industry. Nineteenth-century advertisers increasingly became an essential pre-condition for the survival and growth of the publishing industry [14]. Prior to the 1850s in Britain, advertisements were small, unillustrated and confined to the back pages. By 1880, advertisements were presented with spectacular illustrations (Figure 4).

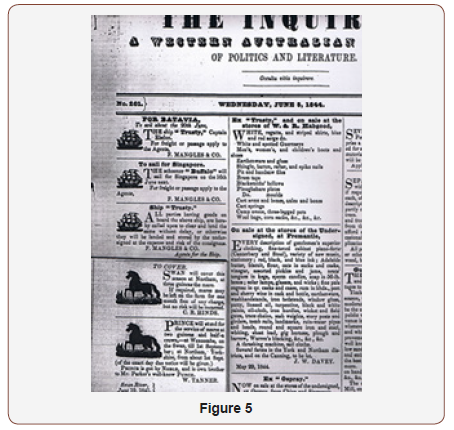

Advertising became an increasingly important aspect of retailing through the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century, not least as the range of printed media steadily expanded. Three modes of advertising stand out: notices placed in the growing number of local newspapers; trade cards and bill heads (often illustrated); and, from the early nineteenth century, advertisements placed within trade directories. The Victorian advertisement exposes materialistic fantasies. It tells of goods that excited the imagination and of mundane realities of everyday life. Fashion advertisements during the mid-nineteenth century were small and not more than a price list or itemized inventory, but by the late 1880s, illustrated advertisements were clearly amongst the most visually arresting in the Victorian periodical press, and reflected consumer interest and the effectiveness of advertising. Although most advertisements were for expensive goods which could only be afforded by the affluent, the illustrated fashion advertisements would have been available to a cross-section of society. From the journals of the day we see that the richer the Victorians became in the latter half of the century, the fussier were their clothes. The bolder and heavier the printers’ typefaces became, the more extravagant the advertisers claim (Figure 5).

In early ads, a person addressed whoever might be interested in his offer. Until the mid-1870s, the majority of clothing advertising was on the front page of newspapers which suggests their importance in society. These advertisements focused directly on material quantity and variety, rather than on convincing readers to purchase goods. Part of the function of advertisers has always been to sell dreams, and the dream they induce with the greatest success is the dream of beauty. In newspaper, journal and magazine advertising, when the attention of women was desired, it was still common practice to start advertisements with the line, “To the Ladies”. An agate-cap heading such as “A Notice to the Ladies- Furs, Furs, Furs” combined the woman interest with the iteration idea.

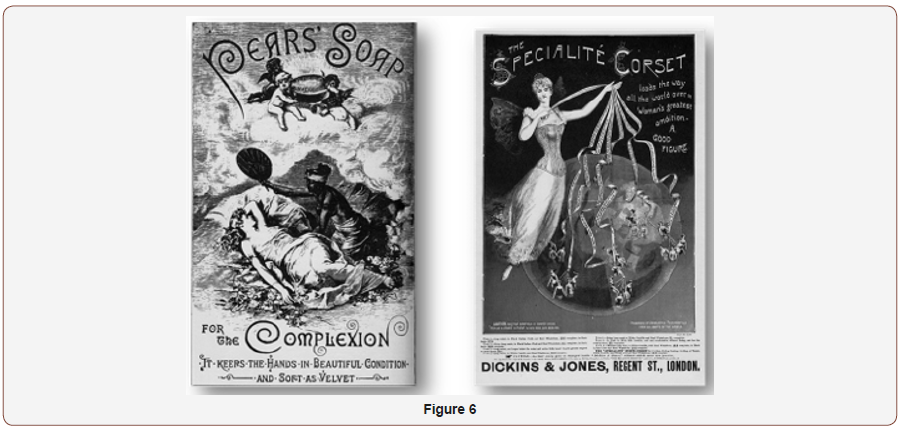

Women were the primary audience for most nineteenthcentury advertisements. Advertisements and related notices in the newspapers and magazines about clothing and finery were an invaluable resource for women. The advertisement became both mirror and instrument of the social ideal. It was possible to create the illusion of the ‘perfect lady’, a beacon of Victorian affluence, via advertisements. Such advertisements would suggest fringes to improve the coiffure, corsets to mould the female figure, baby food which closely resembled human milk in composition, and matching soap for the hands and complexion.

The discourse of advertising soon became a persuading mechanism. Corsets were prepared by a new and scientific process, soaps transformed into magic cleansers for rich and poor alike and nutritious drinks became the liquid life. Influential social icons, i.e., royals, actors, soldiers, beauties, politicians and scholars were also recruited to persuade consumers to purchase goods (Figure 6).

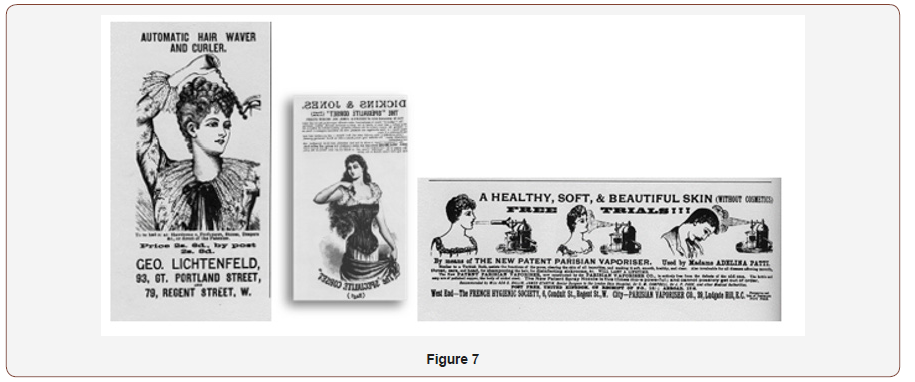

Many Victorian advertisements in Europe was concerned with luxury goods- furs, diamonds, silver, couturier clothes and were primarily focused on the affluent upper-classes of society bringing about conspicuous consumption which enhanced and elevated social status rather than simply satisfying needs. “The consumption of more excellent goods is an evidence of wealth. Elegant dress serves its purpose of elegance not only in that it is expensive, but also because it is the insignia of leisure.” Unquestionably, the upper classes seemed the most probable objective for fashion advertisements, because of their desire to be fashionable and their financial capacity to purchase the advertised items (Figure 7).

Discussion

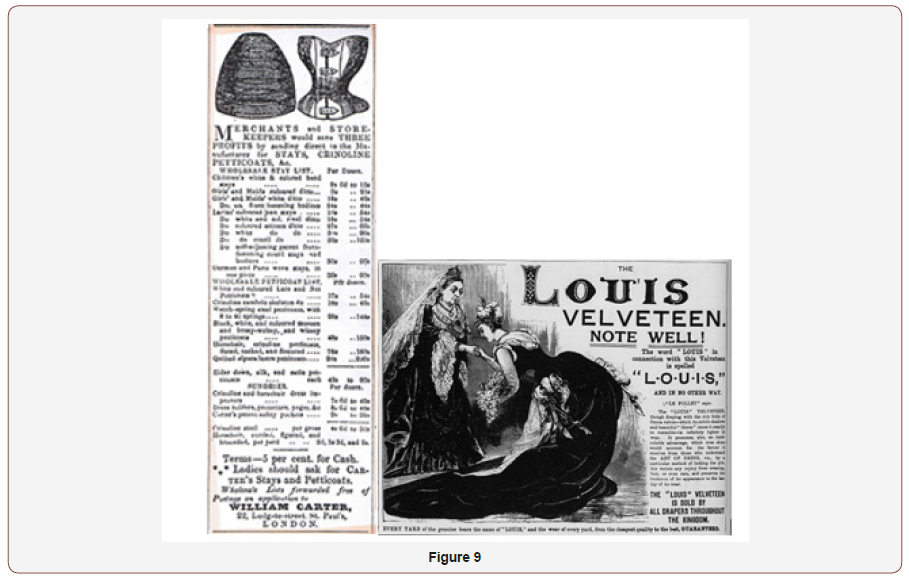

In the early days they advertised a small range of products and brand names began to emerge from 1880. From about the 1880s, the power of advertising replaced the home produced, locally made production with brand-named, nationally distributed goods. Consumers were informed of brand-named clothing, flour, oats, cereals, soap etc., through national advertising. For example, Ladies should ask for Carter’s stays and petticoats. Advertisement from William Carter of London. Nineteenth-century advertisements reflected a domestic ideology and an idealized feminine appearance and were directed towards women, i.e., fashion advertisements including elegant apparel, coiffured hair, adorned hair, fine fabrics, a variety of packaged/convenience food and medicines primarily attracted female consumers.

As Garvey explains, from about the 1880s, the power of advertising replaced the home produced, locally made production with brand-named, nationally distributed goods. Consumers were informed of brand-named flour, oats, cereals, soap etc., through national advertising [15].

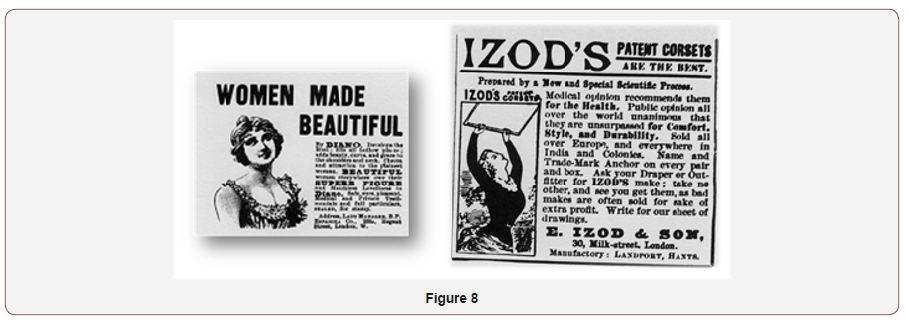

In Victorian Europe, the appearance of monthly articles on the fashions of the day was a significant feature, which delivered information to a circle which had been content to be shut off from such elevating knowledge. The mere fact that such sources of information flourished and multiplied is in itself evidence of a growing taste for refinement of costume, which had hitherto been restricted to a selected few. Contrary to the pre 1852, when the singular fashions had obsessed a small and selected group, during 1852-1865 the rule of fashion was elevated and extended, primarily because of the invention and development of railways, mobility and increasing numbers of ladies’ magazines providing the current fashionable news from the fashion front to the various classes (Figure 8).

As many writers accepted (Leob, Gill, Garvey, Wills and Midgley), women were the audience and the primary objective for most nineteenth-century advertisements. According to Leob, the advertisement became both mirror and instrument of the social ideal. The advertisements would suggest fringes to improve the coiffure, corsets to mould the female figure, baby food which closely resembled human milk in composition, soap which matches for the hands and complexion. “It was possible to create the illusion of the ‘perfect lady’, a beacon of Victorian affluence, via advertisements” [16].

Innovation of advertising methods, such as the use of concoctive phraseology, was a persuading mechanism. Corsets were suddenly prepared by a new and scientific process [17], soaps transformed into the magic cleanser for rich and poor alike [18], nutritious drinks became a liquid life [19]. The influential social icons such as, royals, actors, soldiers, beauties, politicians and scholars were utilized to persuade and induce the consumer who read the advertising. A large part of the Victorian advertisements in Britain was concerned with luxury goods- furs, diamonds, silver, couturier clothes [20].

Most advertisements in relation to fashionable finery were primarily focused on the affluent upper classes of society. For the upper-classes, conspicuous consumption enhanced and elevated their social status rather than simply satisfying their needs. According to Veblen’s theory, “The consumption of more excellent goods is an evidence of wealth. Elegant dress serves its purpose of elegance not only in that it is expensive, but also because it is the insignia of leisure” [21]. Unquestionably, the upper classes seemed the most probable objective for these fashion advertisements, because of their desire to be fashionable and their financial capacity of purchasing (Figure 9).

Fashion advertisements during the mid-century were small and not more than a price list or itemized inventory. By the late 1880s, illustrated fashion advertisements were clearly amongst the most visually arresting in the Victorian periodical press, which portrayed the consumer interest and their conviction as well as the effectiveness of advertising. Perhaps these advertisements or this advertising must have served the whole society, regardless of the class and position. Although most advertisements were involved in the opulence and splendor of goods, only affordable by the affluent, the illustrated fashion advertisements would have indulged a crosssection of society, despite their social standard or literacy. In the colonial context, in relation to colonial Australia, illustrations began appearing in Australian newspapers from 1841 as tiny sketches of horses, ships, logos and trademarks. The first-ever fashion/attire illustration in an advertisement was presented during the 1860s, with the sketched pictures of stays and crinoline petticoats [22]. The Queen appeared or was mentioned in some advertising, nevertheless no other prominent figure was portrayed.

In scrutinizing the pattern of early newspaper advertisements in relation to clothing, approximately ninety-nine per-cent of the advertising was on the front page of all existing newspapers until the mid-1870s, which suggested their importance and position in society. These advertisements focused very directly on material quantity and variety, rather than the manner of pleasing, pleading or convincing the consumers/readers.

Ladies should ask for Carter’s stays and petticoats. Advertisement from William Carter of London [23]. There were advertisements, with brand names, for food, beverages, medicine, hardware and clothing throughout the nineteenth century. In relation to clothing, the underwear; stays, crinolines, and petticoats; textiles such as Louis’ Velveteen [24], were some of the imported brand-named clothing merchandise in nineteenth-century.

The gender aspect of the early advertisements was significant. The nineteenth-century advertisements indeed a commercial interpretation of the domestic ideology and the commercially idealized feminine appearance, were directed towards women rather than men. As scarcely any advertisement illustrated the class or leisured ideal, the regular advertisements such as fashion advertisements; including elegant apparel, coiffured hair, adorned hair, fine fabrics, variety of packaged/convenience food, and remedial medicines, which primarily attracted and facilitated female consumers, revealed the female targeted and subjected cultural/consuming pattern.

In scrutinizing the British advertising culture at the era, although it was centered on gender, the denotation of class and status was detectable. The numerously advertised luxury merchandises; elaborate finery, elegant furniture, expensive food, which could facilitate leisure; was a reflection of social status and position, as well as a graphic depiction of materialistic desires of the wealthy English upper society.

Scientific methods of constructing patterns by the use of body measurements and mathematical calculations were initially introduced to men’s clothing only. An advertisement for Le Somatometre of 1839 shows a framework to be filled over the body to obtain exact measurements for the tailor. From 1870 onwards scientific systems were utilized for women’s patternmaking as well [25].

In nineteenth-century Britain, male fashions were tremendously popular as they published several fashion magazines with illustrated advertisements such as, Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion 1829-1850, Gentleman’s Herald of Fashion 1851-1862, Minister’s Gazette of Fashion 1857-1867, West-End Gazette of Fashion 1865-1877, The Tailor & Cutter 1868-1900, A. Lyne’s Journal 1869-1876, Tailoring World 1895-1899 and The London Tailor 1898; all exclusive to gentlemen [26-38].

Conclusion

In comparing with today’s world, we observe almost identical mentalities and attitudes in modern day consumers, even though the methods, the methodologies and the techniques has changed.

Printing became much cheaper and that propelled advertising practices to another level, and advertising became a business unto itself. As advertising is integrated into each medium, the chronology of modern-day commercialization initiated with the radio in the 1920, video in the 1950s, then the TV and the internet.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Jones A (1996) The Power of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth Century England. Scolar Press, New York, USA, p. 98.

- History of Newspapers. Collier’s Encyclopedia.

- Raymond J (1999) The Invention of the Newspapers: English Notebooks 1641-1649, Clarendon Press, London, p. 20.

- Raymond J (1999) The Invention of the Newspapers: English Notebooks 1641-1649, Clarendon Press, London. P. 9.

- Jones A (1996) The Power of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth Century England, Scolar Press, New York, USA p. 23.

- Jones A (1996) The Power of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth Century. England, Scolar Press, New York. P. 98.

- Cranfield GA (1978) The Press and Society from Caxton to Northcliffe, Longman, London. P. 222.

- Cranfield GA (1978) The Press and Society from Caxton to Northcliffe, Longman, New York, USA, p.224

- Jones A (1996) The Power of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth Century England. Scolar Press, New York, USA, p. 213.

- Jones A (1996) The Power of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth Century England. Scolar Press, New York, USA, pp. 9.

- Leob LA (1994) Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Women, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 5.

- Gill LE (1954) Advertising and Psychology, Hutchinson’s University Press, London, UK, pp. 12-18

- Brembeck WL, Howell WS (1976) Persuasion: A Means of Social Influence (2nd Edn), Prentice Hall, New Jersey, USA, pp. 39-44

- Jones A (1996) Powers of the Press: Newspaper, Power and the Public in Nineteenth Century England, Scolar Press, London, New York, p. 180.

- Garvey EG (1996) The Adman in the Parlour, Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture 1880s to 1910s, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, p. 17.

- Leob LA (1994) Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Women, Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA, p.10.

- (1890) Illustrated London News.

- (1885) Family Circle of the Christian World.

- (1900) Illustrated London News.

- Leob LA (1994) Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Women, Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA, p. 164.

- Veblen T (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class, Unwin Books, London. pp. 64 & 121.

- (1861) The Inquirer.

- (1861) The Inquirer. p. 1.

- (1887) The Western Mail. P. 20.

- Arnold J (1973) A Handbook of Costume, Macmillan, New York, USA, pp. 119-124.

- Kidwell CB (1979) Cutting a Fashionable Fit: Dressmakers’ Drafting System in the United States, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, USA, pp. 11-99.

- Cunnington P (1959) Handbook of English Costume in the Nineteenth Century, Faber and Faber, London, UK.

- Waugh N (1968) The Cut of Women’s Clothes 1600-1930, Faber and Faber, London, UK.

- Ewing E (1984) Everyday Dress 1650-1900, Anchor Brendon Ltd, London, UK.

- Adburgham A (1981) Shops and Shopping 1800-1914, George Allen and Unwin, London, UK.

- Cunnington CW (1948) The Perfect Lady, Max Parrish and Co Ltd, London, UK.

- Garvey EG (1996) The Adman in the Parlour, Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture 1880s to 1910s, Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Gill LE (1954) Advertising and Psychology, Hutchinson’s University Press, London, UK.

- Leob LA (1994) Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Women, Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA.

- Ohmann R (1996) Selling Culture. Verso, London, UK.

- Veblen T (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class, Unwin Books, London, UK.

- Vries L (1968) Victorian Advertisements, John Murray, London, UK.

-

Damayanthie Eluwawalage. Now and Then: The Fascinating Narrative of Fashion and Clothing Advertisements. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 3(2): 2019. JTSFT.MS.ID.000556.

-

Fascinating, Fashion, Clothing, Humanizing, Compositors, Contemporary, Materialistic

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.