Research Article

Research Article

Idea Exchange in The Pleats- The Pleating Workshop as a Research Method

Tsai-Chun Huang*

Institute of Textiles and Clothing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Tsai-Chun Huang, Research Assistant Professor, Institute of Textiles and Clothing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong.

Received Date: October 10, 2020; Published Date: January 27, 2021

Abstract

This paper shares first-hand experience of feedback collection from workshop participants to revise the pleating technique.

Pleating is a sophisticated fabric manipulation that has been practiced for thousands of years. In his 2016 exhibition ‘Manus X Machina’, Andrew Bolton listed pleating as an important couture technique along with embroidery, leather work and other garment production techniques. How pleating advances with technology and the new way to pleat have become issues in the garment production industry.

Workshop preparation offers an opportunity to locate the study in a nonformal ‘laboratory’ condition in which concepts are challenged, presented and examined. Through working with the local community and a design professional in higher education, this research searches for unconventional perspectives from conducting experiments in academic and non-academic contexts and inspirations for future study

Keywords: Workshop; Pleating; Participants; Practice-led research

Introduction

As a type of textile manipulation, pleating progresses with material and technology advancement, and this process can sometimes gain inspiration in workshops with participants from different fields. This research takes the workshop as a research method and reflects on how the process reveals the inspiration to revise the pleating technique. Technological developments in manufacturing processes also affect the way in which we understand the meaning of textiles [1]. Therefore, this study also examines how the perception of pleats and pleating has been changed through the alternatives methods of thermally pleating a piece of fabric.

Literature Review

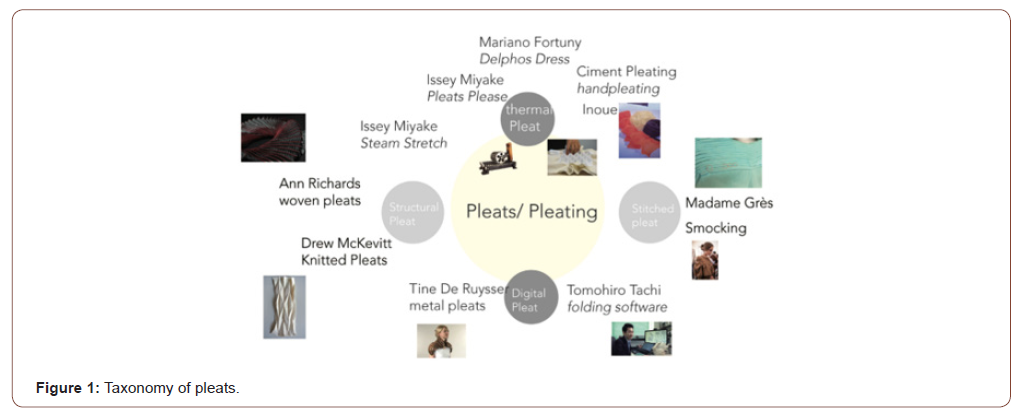

From their exhibition catalogue ‘Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles’ (1999) Matilda McQuaid and Sharon Baurely (for their PhD research, An Exploration Into Technological Methods to Achieve Three-Dimensional Form in Textiles, Fashion and Textiles, Royal College of Art, 1997) [2] categorized pleats into three groups according to the production method. The first type is ‘manual processing’ and refers to the pleats that are heat pressed by irons with hands. The second type is the ‘continuous machine method’ which refers to the pleats that are achieved through automatic machines. This type is currently the most common method of producing pleats in the industry. The last type of pleats is the ‘hand pleating method’ which uses two pieces of kraft paper moulds to sandwich the textile and through which heat sets the form via steaming [3]. All three types of pleats are thermally realized, and the classification criteria depends on if the pleat is formed by hand, machines or kraft paper, with the exclusion of other ways of producing pleats. Given the recent technology development, I propose an alternative taxonomy according to the mechanism of construction and the way in which the pleat is formed. I classify pleats into four types: ‘stitched[1]’, ‘thermal[2]’, ‘structural[3]’ and ‘digital ’ pleats (Figure 1). These classification helps to demonstrate and reconsider how makers move between hand, machine and textile manufacturing. This paper would focus on teaching the production of ‘thermal’ pleats and how the workshop experience helps me revise the pleating method.

We can trace the history of thermal pleats to ancient Egyptian and Greek clothing. Before the use of flat irons, people in ancient Greece used thumbnails to crease and fix the pleats. This way of producing pleats is still applied in some rural areas in Greece, where peasant women pleat their national dress bonnets[4][4]. The ancient Egyptians (approx. 500-450 BC) would hand-fold the fabric and then use strings to stabilize the pleats. Later, the tied fabric is soaked in thin starch and then dried under the sun.

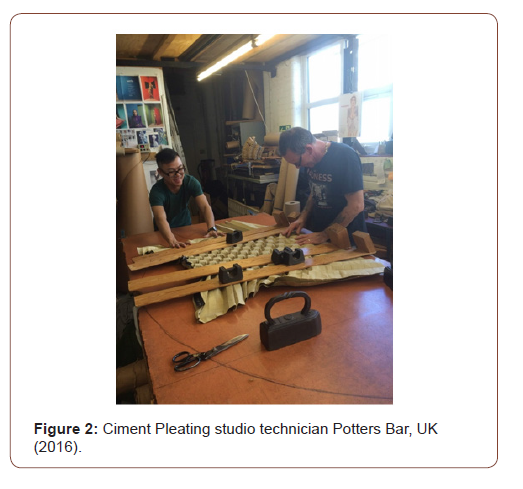

In my pleating workshop, I incorporate the hand pleating technique I learnt as a studio technician in Ciment Pleating Ltd. in 2016. During hand pleating, the fabric is sandwiched between two kraft paper moulds, stabilized by strings and then fixed by steams. This procedure is how general thermal pleats are produced. Polyester fabric optimally reacts to this method as this type of synthetic material contains heat-set mouldability [5].

Methods

Learning to pleat in a professional pleating studio (Figure 2) and producing pleats through my own hands are indeed efficient ways to learn pleating, and this research has benefited from these two research methods of understanding pleats and pleating quickly. However, to collect fresh ideas to produce pleats in a novel way, I needed to interact with people who are new to pleats and the pleating technique to observe how they respond to this fabric manipulation. Furthermore, this study situates itself as a projectled research, so the method applied could be more flexible than just traditional field study , consulting references or conducting reference reviews.

Foot Notes

1‘Stitched pleats’ can be more easily understood if it is connected to smocking. When producing smocking, threading is necessary to fix the pattern, thereby making the structure and the fold static rather than mobile. Madame Gres’ works demonstrate a good example of stitched pleats. In her design, each pleat is creased by hand and stabilized by threading underneath, as observed from the reverse side of the garment.

2‘Structural pleats’ is a unique category that I distinguish from the other types of pleats. This type involves thoughtful calculation of woven or knitted structures. Structured pleat textiles will contract into the calculated forms upon emerging from the loom machines or the needles. This outcome arises because of the tension of the stretch yarns or the position of threads. This pleat type is distinct as it is not readily affected by humidity and pressures like the post thermal produced pleats which predominates in the market. The Miyake’s steam stretch and Richards’ woven pleats are woven pleats, and knitted pleats have been taught as a fundamental knitting technique in textile design education.

3Digital pleat is a category specific for creating for the digital ages in which designers adopt digital tools to produce or prototype their pleated samples in tangible and virtual forms. Examples include Tine de Ruysser’s metal pleats and Tomohiro Tachi’s dedication on pleating software research.

4In their book ‘Fortuny’, the reference Historie du costume dans l’antiquite antique by Leon Huezey was mistakenly cited by Deschodt and Poli. The correct title is Historie du costume antique d’apres des etudes sur le modele viviant.

Jane Mills encourages researchers conducting qualitative research to develop their own research method through adopting and adapting existing methodologies to match their research contexts.

Flexibility in the use of qualitative methodologies is essential to create a best-fit with the research question, and to optimize the desired outcome [6].

As a practice-led research, this study seeks to expand not only the methodology, but also the fundamental research methods to obtain the tacit knowledge embedded in the production process.

Ørngreen R, et al. proposed the workshop as a means, practice and research methodology that offers nuances in its own existence. As a research methodology, the workshop is ‘designed to fulfil a research purpose: to produce reliable and valid data about the domain in question [7]. They believe that workshops could be viewed as a platform that help researchers identify and explore complex work and knowledge.

Workshops enable researchers to potentially draw out fruitful information from participants to enrich the study [8]. In addition, constructive feedback and a collaborative discussion between facilitator and participants are crucial elements for a successful workshop [9]. Specifically, Ahmed and Asraf suggest that it is important to let participants feel their voices are heard and the written feedback could help improve the consecutive sessions.

A workshop for art and design research is a place to elicit thoughts [10], and knowledge flow should not be a didactic or unilateral [11]. A workshop should be a form of encounter for knowledge democratization and reciprocity (ibid., p.412), enrich the design process and provide spaces for shared exploration [12]. For this type of skill-teaching workshop with a certain level of exploration, the process itself is the actual end result [13].

Therefore, this research would like to reflect on how workshop experiences lead to new thoughts and give room for fresh ideas on novel pleating methods to flourish.

The Workshop Processes

After conducting a few pilot workshops with research colleagues as trial sessions, the workshop format emerged organically. The responses from colleagues after the trial sessions provided practical suggestions on how to deliver the content in a clear structure and in time to reach suitable workshop management.

Workshops usually start with a brief introduction to pleating history, key designers who adopt pleats for their design, paper folding practice to produce their own paper moulds, pleating with a piece of fabric, garment making and pleating an entire garment with large size paper moulds. By following this structure, participants need not visit a professional pleating studio where they can acquire a sense of the complete pleating process from beginning to end [14- 16].

The workshops are delivered in two levels. The entry level workshop is a walk-in activity in which participants hand-fold preprinted thick paper as paper moulds and use the fabric provided (such as chiffon, organza and plain weave polyester) to experiment. The advance workshop could include garment- or accessorymaking, and this type requires a certain knowledge of pattern making and sewing skills [17,18].

Advance workshops usually end with a group critique whilst participants wear their own design (Figure 3). This part generates positive feedback through group discussion, and participants gain better understanding of different pleating techniques in relation to some samples showed at the beginning at the workshop, for example, Miyake’s Pleats Please collection.

The data in this research were collected participant interviews during the hands-on folding process. Since October 2015, I have held several pleating workshops: 1 in the Czech Republic, 4 in the US, 6 in the UK, 24 in Taiwan and 23 in China[5][19-21].

Result and Discussion

The research participants come from a wide range of backgrounds, including those completely new to design or members of fashion design educators. However, the current participants are more or less uniformly ‘new leaners’ in relation to pleating technique. This situation creates an advantage in that the participants are unencumbered by the principles of pleating I teach and could offer fresh perspectives for the creation and usage of pleated fabrics. For example, one costume designer who attended the 2019 Prague Quadrennial workshop disregarded the regulation about the size of the garments to be pleated, so she received the outcome of partially pleated section for which a 3D-pleated form emerged from the flat plane of the textiles. Furthermore, she decided to cut and sew sections of pleated fabric together, thereby creating a drapery 3D structure (Figure 4).

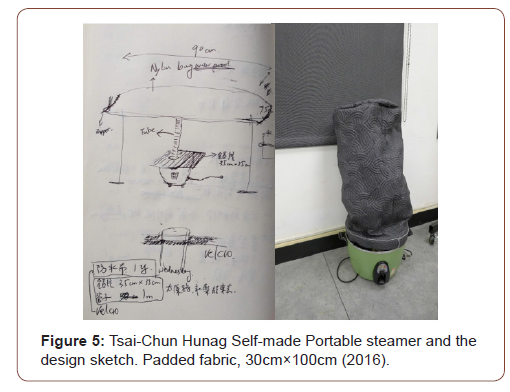

More invitations to lead workshops resulted from participants’ positive feedback and recommendations. This circumstance fed back to my study for adopting the workshop as an essential research method into the investigation of pleating techniques. Collective experiences with workshop participants by using minimal resources has challenged me to redevelop the possibility of pleating without professional machinery and industrial tools and under time limits with undeveloped skill sets. Under such an abnormal environment to conduct pleating, I had the opportunity to test different approaches and methods. The pressure to deliver workshops in a domestic environment also encouraged me to invent a portable steamer to facilitate the conduct of pleating workshop in different countries (Figure 5).

In a workshop for the Design for Stage and Film course at the Tisch School of Arts in New York University, I tested testing different types of machine pleating technologies together with the participants. After demonstrating a Geneva hand-rocker fluter from 1868 (Figure 6) and showing Fortuny’s patent diagrams, an MFA student asked whether I had thought about producing my own pleating machines and applying patents for them. This question really struck me such that I began to consider the functions of nextgeneration pleating machines. Perhaps, one of those machines can pleat a 4-way stretch folding structure, so that I could replace the kraft paper technique to save hand-labour. This rethinking also helped me to undertake deeper investigation and analysis of the fundamental qualities of pleats and pleating in terms of the way the fold patterns stretch and when a pleat become a pleat.

Back in my hometown of Taiwan, I incorporated a studio visit for workshop participants. Sinta, a long-standing pleating factory in Taiwan, is located in New Taipei City. During the visit, participants not only acquired knowledge of the local hand-pleating method which differed from that of the Ciment Pleating in London, but also obtained a basic proficiency of machine pleating. Furthermore, participants enthusiastically asked the CEO, Leo Liu, questions which opened new and useful thoughts for this research.

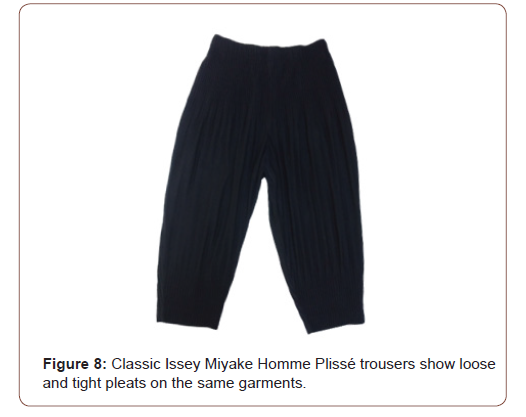

During the 13 August 2016 visit, a participant with a fashion design background asked, ‘How [can] a single machine produce different types of pleats?’ Liu then demonstrated the mechanism of the machine that could vary the density and the scale of the pleats. By changing the number of clamps on the same row (Figure 7), the machine can create tight and tiny pleats together with loose and large pleats on the same piece of fabric. It was through

Foot Notes

5The workshop in the Czech Republic transpired during the Prague Quadrennial. In the US, these workshops took place at the Design for Stage and Film at Tisch School of Arts NYU, Fashion Design at Parsons School of Design, and for the faculty members at the Fashion Institute of Technology. In the UK, the workshops were offered at ‘Across RCA’ and ‘Work in Progress Show’, Royal College of Art, Instituto Marangoni London, East Coast College (Lowestoft Campus) and at ‘Shaping Your Area’ in the Roman Road Yard Market organized by St Margaret’s House. In Taiwan, the workshops were held at the Xue Xue Institute, Shih-Chien University, ‘In Circle’, Songshan Cultural Creative Park and Municipal Hongrenguomin Junior High School. In China, the workshop locations include ACG Chongqing, ACG Changdu, ACG Guangzhou, ACG Shenzhen, ACG Shanghai, ACG Zhengzhou, ACG Dalian, ACG Hangzhou, Southwest University, Shanghai Design College of China Academy of Fine Arts, Sichuan Normal University, International School of Nanshan Shenzhen, Sanda University, China Construction Bank Dalian Branch and Zhengzhou No.1 High School.

this occurrence that I understood how the Issey Miyake Homme Plissé trousers (Figure 8) were made. This experience helped me comprehend the possibilities and restrictions of machine pleating better than before [22].

6This ‘discovery’ became part of my research into understanding Fortuny’s pleating technique and I later established a series of workshops on Fortuny on the basis of this encounter

Another participant, an office worker without any design experience, asked ‘What is the history of the pleating industry in Taiwan?’ The answer gave us a brief understanding of how Taiwan adapted Western technologies as part of the manufacturing boom around the mid-late 20th century. In the 1970s, clothing factories in Taiwan had high demand for machines to meet the large production requirements. Liu explained that Taiwan was the world factory for the garment industry at that time and produced bulk quantities of clothing. However, these manufacturers did not have the budget to purchase pricey German pleating machines. Hsin Tai Cloth Folding Co. Ltd. imported one machine from Germany and it to study the structure to build their own version of a pleating machine to supply the industry in Taiwan. After that successful experience, Taiwan began to export pleating machines to foreign countries [23]

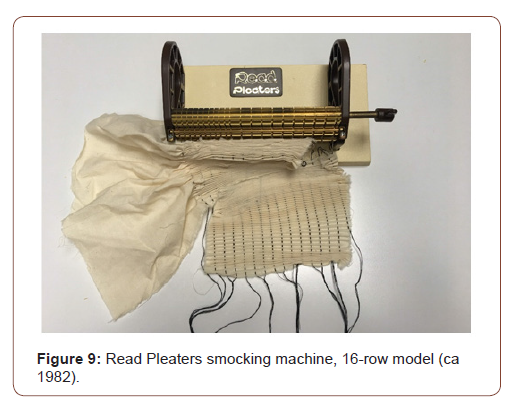

The last example is from the workshop at the Xue Xue Institute, Taiwan, in 2017. A 9-year-old child asked me the difference between nui shibori, a type of shibori technique that requires needles to thread the fabric to tie the design, and smocking, after demonstrating a 16-row Read Pleaters machine (Figure 9). I realized then that both techniques need threading to contract the fabric, and shibori and pleating many similarities and contrasts as well.

These two fabric manipulations are fundamentally similar as the shibori is actually a type of natural fibre pleating which is ironed flat after dying to focus on the colour pattern whilst pleating maintains the 3D structure after thermal fixation. Shibori can be understood as a kind of pleating which uses a hot dye solution to replace steam as another way to thermally mould the textiles.

Henceforth, I viewed shibori from another perspective and explored it as one of the potential pleating methods with workshop Participants[6] (Figure 10).

From the workshops above, participants can be divided into two categories according to their background (design and non-design related) and demonstrate distinct perspectives on the questions they ask. Participants with design-related experience tend to adopt the rules they just learned and adapt them to their own designs, thereby creating novel silhouettes. In addition, the ideas they offer are more likely related to pleating machines and their mechanism and are very insightful for this pleating research. Participants without design-related backgrounds tend to ask questions that are related to the history of the technique or the industry from an archaeological perspective. Furthermore, these participants would question the differences of existing techniques which would build connections between these skills that I have not conceived of.

Conclusions

As facilitator in several pleating workshops, I have communicated and learned alongside participants. The entire journey helps me create my own pleating techniques. These techniques include a portable steamer and adopting shibori as a pleating method to experiment with Fortuny pleats. More than that, the process of rethinking pleats and pleating also provides me new thoughts about how pleats can be represented in ways other than the conventional kraft paper molding method. The discourse is embedded in the pleats which helps shape the research in the future.

The workshop as a research method also offers a remarkable opportunity to incorporate historical, theoretical and practical materials, such that the interaction and overlap of these fields can be discovered. On the one hand, the demand to prepare the workshop clearly forces the facilitator to condense the knowledge in a clear and deliverable way. On the other hand, the process of conducting a workshop with participants offers the effect of locating the study in an informal ‘laboratory’ condition in which concepts are challenged, presented and examined, thereby rejecting the traditions of professional dialogue in the academic and practice setting.

Workshop preparation is a stimulus to reorganize the study on pleats and pleating. This endeavor is how the category of pleats – stitched, thermal, structural and digital–emerged. This categorization not only enables participants to use this taxonomy as a principle to distinguish and understand the different types of pleats they encounter, but also paves a distinct route for future researchers who conduct pleating study to position themselves on which type of pleats need greater attention.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Igoe E (2018) Change matters: theories of postdigital textiles and material design. Design Research Society 2018 International Conference: Catalyst. Design Research Society, Limerick, Ireland.

- MCcarty C, MCquaid M (1999) Structure and surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles. Museum of Modern Art, New York: Museum of Modern Art, USA.

- Baurley S (1997a) An exploration into technological methods to achieve three-dimensional form in textiles. PhD Thesis. Royal College of Art, UK.

- Deschodt AM, Poli DD (2000) Fortuny. New York: Abrams, USA.

- Hopkins D (2008) A Teacher’s Guide to classroom research. Maidenhead: Open University Press, UK.

- Mills J (2014) Methodology and Methods. Mills J, Birks M (edt), Qualitative Methodology: A Practical Guide. London: Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 31-44.

- Ørngreen R, Levinsen K (2017) Workshops as a Research Methodology. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning 15(1): 70-81.

- Ahmed S, Asraf RM (2018) The workshop as a qualitative research approach: lessons learnt from a “critical thinking through writing” workshop. The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication pp.1504-1510.

- Spagnoletti C, Spencer A, Bonnema R, Mcnamara M, McNeil, M (2020) Workshop Preparation and Presentation: A Valuable Form of Scholarship for the Academic Physician.

- Openshaw J (2015) Postdigital Artisans: craftsmanship with a new aesthetic in fashion, art, design and architecture. Amsterdam: Frame Publishers, Netherlands.

- Richards A (2012) Weaving Textiles That Shape Themselves. Marlborough: The Crowood Press, UK.

- Heuzey L (1922) Histoire du Costume Antique. Paris: Edouard Champion, UK.

- Johnston L (2015) Digital Handmade: craftsmanship in the new industrial revolution. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, UK.

- Baurley S (1997b) Some aspects of contemporary Japanese Textiles. Textile Forum 97: 35-36.

- Bolton A (2016) Manus X Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: The Met Publishing, USA.

- Braddock Clarke SE, O'Mahony M (2005) Techno Textiles 2: Revolutionary Fabrics for Fashion and Design. London: Thames & Hudson, UK.

- Desveaux D (1998) Fortuny. London: Thames & Hudson, UK.

- Finley S, Knowles JG (1995) Research as Artist/ Artist as Researcher. Qualitative Inquiry 1(1): 110-142.

- Kalajian L, Kalajian G (2017) Pleating: Fundamentals for Fashion Design, Atglen. PA: Schiffer Fashion Press, USA.

- Keay D (1985) The Book of Smocking. London: Collins.

- Koike K (2016) Issey Miyake. Kitamura M (edt), Koln: Taschen. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, UK.

- Savin-Baden M, Major CH (2013) Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. Oxford UK: Routledge.

- Thompson R (2014) Manufacturing Processes for Textile and Fashion Design Professionals.

-

Tsai-Chun Huang. Idea Exchange in The Pleats- The Pleating Workshop as a Research Method. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 7(4): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000667.

-

Workshop, Pleating, Participants, Practice-led research

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.