Mini Review

Mini Review

How Meaning Can Inform Fashion Design – The Semantic Turn

Helge Löbler, Institute for Service and Relationship Management, Leipzig University, Germany.

Received Date: August 24, 2020; Published Date: September 18, 2020

Abstract

This review presents humans-centered design and shows how it can inform fashion design. The core insight of human-centered design is that people do not respond to things (material and immaterial) as they are but act according to what they mean. Thereby meaning is co-created on different levels of artificiality. These levels reach from pure product to any kind of discourse by which people refer to their experiences or thoughts and feelings. One important conclusion is that designers do not create the meaning of the designed alone but with a whole community involved and connected to the designed.

Relevance of meaning

On a BBQ-party, last summer a friend of mine approached me with the question: “Are you Major Tom?” My mother hated blue jeans and so I did not get one when I was a child. For my friend my silver jacket induced his question. My mother associated blue jeans with belonging to the worker class in society. These are just two examples that clothes have meaning not only for the people wearing them. Not only fashioned textiles have meaning but also ordinary clothes without any kind of recognizable label or alike. “The fundamental insight of human-centered design is that people never respond to what things are but act according to what they mean to them” [1]. With his book “The semantic turn; A new foundation for design”, Krippendorff [2] changed design thinking. This thinking and understanding of meaning is applicable in general for the artificial. Thereby “artifacts make possible something that would not come about naturally “ [3]. Artifacts are all human creations weather tangible like clothes or intangible like brands or images. This thinking of design put meaning in its center; “Meaning is the only reality that matters” [1]. The meaning of clothes transcends all areas of the world. It is not limited to artifacts. However here artifacts are in the focus.

Meaning and Artificiality in Design

In postmodern design-thinking meaning is not a characteristic of a thing or an entity. Meaning emerges through a process of recursive operations including interaction and indicating. Löbler and Wloka have shown how meaning emerges when recursive operations are working [4,5]; Following Wittgenstein [6], they found that words either refer to other words or to practices. These references are loops either between words or between practices and words. Think a moment about the word “catwalk”. We know that there are never real cats on a catwalk. Originally, catwalks were minor walkways on ships or backstage in theaters. When one is confronted with this word the first time, one has no idea of its meaning. To understand it meaning the word is connected either to other word (explanations) or to the “reality”. However, to really understand the term one has to see and probably experience what happens with and on a catwalk (connecting the word to a practice).

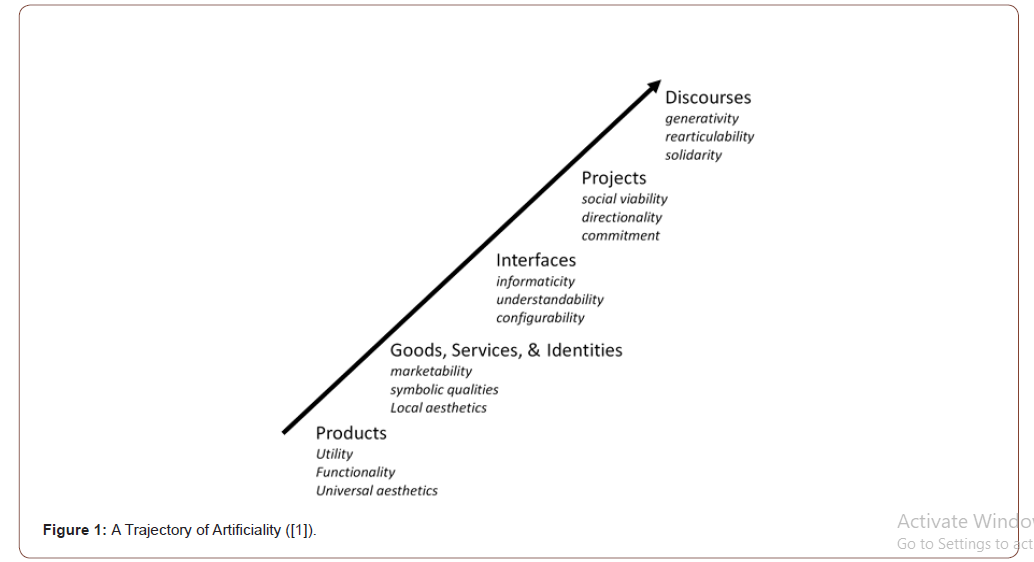

The meaning of a catwalk is very different for models compared to the audience or other actors in the scene. It is important to have a word for the artificial; otherwise, it could not be communicated. “to succeed, artifacts must survive in language or fail” [1]. Therefor Krippendorff described a trajectory of artificiality that goes from product (design of industrial products) to discourse (Figure 1) [1].

Products in the industrial world were designed according to utility, functionality and aesthetic aspects as end products for “endusers”. The textile industry still offers many clothes of this kind from ordinary jeans to simple underwear. These products have meaning mainly for those who wear them.

Goods, services and identities were designed mainly with respect to recognition, attraction and consumption. Important was their marketability and their symbolic qualities. Brands like Gucci, Prada etc. became important and still play a major role. These brands have a high-level of symbolic quality. These goods and services unfold their meaning in society and special events. They are used to signal who the wearer is apposed to be. They create the identities of their wearer.

Interfaces enabled “end-users” to co-design their textiles. Like spread shirt enabled the user co-design t-shirts. Interactivity, understandability and adaptability are of major concern in the design process.

Multi-user-Systems (networks) enable and facilitate cooperation and coordination of human practices across tome and space. These multi-user-systems are indispensable during the corona-pandemic keeping the fashion business running.

Projects reflect the complexity and the cocreation activities of multiple actors in the scene. This is well reflected in the development of fashion design system-products [7] where either UX design refer to users, context and system with the user experience in the center [8] that is communicated by language use and discourses, leading to the final level of the trajectory.

Discourses emerge in communities where social realities are cocreated by use of language. Influencer are often part of these communities.

conclusion

Hence, meaning emerges out of recursive operations between relevant actors in the scene. Designers are no more the master of the meaning of textile artifacts. They become enablers for opportunities of co-design. The meaning of these textile artifacts is co-created by many actors and is the orientation for what people like to wear and like to buy. Particularly in clothes and fashion design “meaning is the only reality that matters” [1]. However, meaning is neither created nor controlled by designers anymore. While Joseph Beuys claimed for everyone to be an artist i.e. to be able to create artificiality, we can now claim that everyone is a designer as everyone is part of a meaning creating community by creating artificiality.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Krippendorff K (2011) Principles of Design and a Trajectory of Artificiality. Journal of Product Innovation Management 28(3): 411-418.

- Krippendorff K (2006) The semantic turn. A new foundation for design. CRC Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, USA.

- Krippendorff K, Bermejo F (2009) On communicating. Otherness, meaning, and information. Routledge: New York, USA.

- Löbler H, Wloka M (2015) Loyalty’ Between Talk and Action – Meaning as Eigenforms of Recursive Operations. In Always ahead: Ideen für das Marketing; Bartsch S, Blümelhuber C (edts), Springer Gabler, Germany.

- Löbler H, Wloka M (2019) Customers’ everyday understanding of ‘value’ from a second-order cybernetic perspective. Journal of Marketing Management 35(11-12): 992-1014.

- Wittgenstein L008) Philosophical investigations. The German text, with a revised English translation, (3rd edn), Blackwell: Oxford, Malden, Mass, USA.

- Visoná PC, De Souza HG (2019) Strategic Design and UX Design Approaches in the Development of Fashion Design Systems-Products. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 3(4): 1-6.

- Kujala S, Roto V, Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila K, Karapanos E, Sinnelä A (2011) UX Curve: A method for evaluating long-term user experience. Interacting with Computers 23(5): 473-483.

-

Helge Löbler. How Meaning Can Inform Fashion Design – The Semantic Turn. 6(5): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000649.

-

Fashion design, Semantic turn, Clothes, Catwalk, Textile, UX design

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.