Research Article

Research Article

Fashion Design Entrepreneurship: Skills and Solutions to Create a Fashion Business

Clara Eloise Fernandes, Associate professor, University of Beira Interior, Portugal.

Received Date: June 21, 2019; Published Date: June 28, 2019

Abstract

Purpose: This study proposes a vision of entrepreneurship in fashion design. Higher-education courses have adapted, and fashion design courses have evolved and moved to a more entrepreneurial concept, as a generation of fashion designers has transformed past experiences and professional vision to become entrepreneurs. Authors and reports linked to entrepreneurship observe more than ever the importance and necessity to bring entrepreneurship very early to classrooms. Studies are more divided on that opinion and show that the introduction of such concepts in early stages of education can be prejudicial for the future of entrepreneurship if those concepts are poorly taught to students.

Methodology: This study employed a mixed-methods approach, as it considered the use of questionnaires to collect data from students and recently graduated students from fashion design schools, in Portugal and abroad; and semi-structured interviews to collect opinions of three main groups of industry professionals: fashion design entrepreneurs, solvers, and specialists. Linear regression & multivariate linear regression was used to analyse the quantitative data obtained, using SPSS. For the qualitative data obtained through interviews, QSR NVivo was used to analyse and encode answers. Finally, a project methodology was used to create a digital platform, proposed as a solution in this study.

Findings: Findings obtained in this study show a lack of support from entities for fashion-related ventures, as well as an evident lack of entrepreneurial thinking in fashion design courses, translated by enormous difficulties for young fashion designers willing to create their own business. Therefore, the need for a solution helping fashion design entrepreneurs was also clearly highlighted by the results obtained. Considering the results obtained through this study, a model for the creation of an entrepreneurship platform will be proposed to create value in the fashion industry.

Research limitations: The main limitation of this study is related to the definition of entrepreneurship itself, as many authors still diverge on this subject. Adding fashion to this topic is also controversial, as the definition of a fashion entrepreneur as yet to be made. Although highereducation courses have made transparency efforts in order to clarify their curricula, this study shows that the specificities presented on the courses and institutions official pages are not very easy to dissect, as many courses present business creation as a potential outcome, without referencing any specific topic on this subject in their curriculum.

Originality/value: This study inserts itself in a multidisciplinary field, mainly composed of two great areas: fashion design and entrepreneurship. The creation of this new subject and the parallelism created between design thinking and entrepreneurial thinking is also crucial. Moreover, the creation of value in the fashion design industry is the main goal here, as it is believed that fashion design SMEs can change the very controversial fashion and textile industry by adding new solutions and value to this billion-dollar market.

Introduction

The Portuguese textile and clothing industry have indubitably experienced many changes in the last few years. After the international crisis that stroke hard the economy of many countries, the crisis has been the catalyst for unemployment and austerity as its consequence. However, countries like Portugal are showing a real evolution since those dark times. The textile industry of Portugal has ended the year 2016 with 5063 million euros in exportations, a number that had not been reached since the beginning of the century [1], encouraging and pushing the Portuguese textile and clothing industry further into former previsions made by the director of ATP (Textile and clothing industry association), Paulo Vaz. Such encouraging numbers are also going towards ATP’s recent investment and plan to gain even more visibility and promote a “Made in Portugal” strategy [2].

Portugal has also experienced a major augmentation regarding higher-education demand from students. Fields like fashion, apparel and textile design have seen the number of entering students increase in their higher-education courses, considering years 2009/2010 in comparison to 2015/2016 [3,4].

Entrepreneurship has also been unquestionably one of the most used words in the past few years, in Portugal and internationally. In Portugal, such affirmation can be confirmed through the number of entrepreneurial models and incentives proposed and created, most of the times linked to regulatory proposals made to emphasize such ventures [5]. In this context, entrepreneurship has become more than something achievable with “luck” and is now considered by public opinion on a global scale as an objective of improvement by many countries, seeing an opportunity and solutions through the growth of entrepreneurship.

More generally, students coming from various fields related to creative arts may benefit considerably from an entrepreneurial mindset, as innovation and multidisciplinary contents are part as these fields as they are part of entrepreneurship itself and can very well lead to a variety of jobs [6]. On the other side, the fashion design field has come to adopt entrepreneurship in another way for the past few years, in the sense that it can be conceded that some individuals have always created their businesses in the field, even if entrepreneurship cannot be reduced to such definition.

In such circumstances, the fashion industry has come to understand the need to innovate in an ever-changing field that comes across crisis on a daily-basis [7], even if on a national level, many are the family SMBs that cannot evolve and grow through innovation, entangled in their traditions, many times associated with the need for family union and only decider of the business’s future [7].

As governmental entities have understood the importance of entrepreneurship for the future, many studies are also being made to determine whether or not entrepreneurship education can be the engine for a new generation of entrepreneurs [8-12].

Years after the most recent economic crisis that stroke the world, it is important to reflect on the current reality in which our society inserts itself, as well as how the powerful fashion industry has seen a new generation of fashion design entrepreneur rise, in order to change a paradigm where only fast-fashion and historical luxury brands were in.

Even with the recent numbers of unemployment keeping at their lowest since 2009 [13], Portugal is still sixth in the ranking of highest unemployment rates in the European Union, and fourth when only considering the Eurozone [14]. More importantly, youth unemployment is still a massive problem for the country, as its rate was 28% in the last trimester of 2016, according to the National Statistics Institute (INE), putting young people between the ages of 15 and 24 years old in a critical place [15].

According to Thomas Friedman, editorialist at The New York Times, paradigms have changed, and generation used to the reality of finding a position after graduation are now in need to create their way into the job market by becoming self-employed, in comparison to the previous generation that “had it easy” [16]. In Portugal, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) lead the numbers, generating low rates of employment at the time [17]. As the socioeconomic frame in which we are inserted has come to create an impulse and evidence the necessity to develop alternatives to traditional jobs or, when they do not exist, created through new businesses, entrepreneurship can become a solution.

According to the European Commission 2008 report on entrepreneurship education, up to 20% of students who participate in an entrepreneurship education program in secondary school will later start their own company. However, as the primary objective of this investigation aims to understand entrepreneurship as a potential solution for young fashion designers, entrepreneurship education will be approached in the higher education environment. Moreover, this study will also approach the definition of the word entrepreneur [18,19], as many still reduce it to the creation of a business, yet, being an entrepreneur is far more than creating selfemployment [20-24].

Furthermore, by exploring entrepreneurship in the fashion design field, this study has for objectives, firstly, to clarify if fashion design higher education programs are prepared for the new challenges of a society always more directed to entrepreneurship; secondly, to understand what specific skills and attitudes young fashion designers lack when it comes to creating their venture in the industry and finally, and thirdly, an exploration of existing solutions aiming to help fashion design entrepreneurs will be made as well as a search for qualities and functions that could be gamechanging.

This study inserts itself in a research gap, where very few studies address fashion design entrepreneurship as a field. This topic, which is very new regarding scientific research, is approached locally and globally, to contribute to the scientific exploration of fashion design and entrepreneurial activity in the field. Moreover, this study seeks to understand who are these fashion design entrepreneurs in Portugal and abroad, as well as comprehending their stories, the point of view as professionals of the industry, the main difficulties they encountered in their journey, and most importantly, if fashion design higher-education can contribute to the increase of such behaviour.

A mixed-method approach is used to cover as much information on both sides of this issue [25]; fashion design students in their senior year will be inquired as well as recently graduated students and on the other side of the fence. On the qualitative analysis side, three groups of distinctive professionals related to the fashion industry will be interviewed to understand the crossroads between entrepreneurship and fashion design.

The results obtained through this analysis aim to contribute to the scientific research in the field by choosing a topic of investigation socially relevant, a problem that belongs to the disciplinary field of design, using a model that can be applied in future investigations, and finally, a process involving users [26]; as the results obtained will directly contribute to the creation of a solution, proposed here as a model, aiming to help fashion design entrepreneurs.

Research Questions

In an interview on the French late show “On n’est pas couché” [27], Olivier Rousteing, creative director at Balmain reflected on his dream as a young child, knowing that he liked to design clothes at a very young age and declared that for him, having a passion was great, but it would be even better to turn it into a job. Rousteing also proclaimed that he senses that this is an actual issue among young people nowadays, as many of them dream to turn that dream into a profession but are never able to. As the scientific field of fashion studies is still very recent [28] the study of multidisciplinary topics involving fashion design is crucial, this study inserts itself in this logic, as it aims to comprehend the relation between fashion design and entrepreneurship.

The challenges and opportunities that come into the path of Fashion Designers is the core of this investigation, considering higher education and its transcription on the job market. The discussion of such thematic develops itself around a set of research lines, considering the education of Fashion Designers: youth unemployment that affects almost every field of activity, the professional skills of these students leaving the educational system, the lack of experience from these young people at the end of their education, as well as the perspective of self-employment.

Considering for that matter fashion design as the nucleus of this research and the particularities of fashion design research [29,30], the following research questions appear: are fashion design higher education courses prepared for the new challenges ahead, in a society that is more entrepreneurial than ever? What specific skills, knowledge and attitudes do young designers lack of to be finally able to launch their venture in this particular field? What are the solutions that are created or can be created to help young designers aspiring to become entrepreneurs? These are the main lines in which this study inserts itself.

The research questions are based on all the previous investigation made to this moment, and it is believed that they reflect what Moreira da Silva interprets as the four conditions essential to produce an investigative work in design: “the problem must belong to the disciplinary field of design, the methods used must construct themselves into a model that can be applied in futures investigations or in the profession of design itself; the topic of investigation must be socially relevant, the process must involve the users” [26]. The four conditions presented by Moreira da Silva were adapted in the context of this study and were used as a guide to elaborate the following figure, demonstrating the importance and articulation of the research questions.

In Figure 1, it can be observed that the first question reflects the necessity to understand if students from higher educational programs developed the necessary skills to face the challenges of an entrepreneurial society. For Frideman T [31], developing skills and being innovative is crucial, as being able to use information that has been taught in the classroom is more important than the information itself. Through the research that was previously conducted, it can be noticed that many factors are contributing to a devaluation of education, as it was the case for the Bolonha process. This depreciation that was also the object of study of many researchers of the design field, namely Alexandra Cruchinho, who approached this thematic in her doctoral thesis entitled “Design- A construção continua de competências” [32].

The second question approaches the necessity to bet on developing new skills that will allow students to create their own brand or business, during the process of graduation, a time when the designer must take a decision regarding the path to follow: joining the industry or starting an entrepreneurial career.

“The education of designers should not be exclusively about the know-how, focusing on technical abilities, technologies and methodologies that are not sufficient on their own, but should focus on knowledge, knowing how to be, how to interact and communicate, with the dominance of skills related to leadership and coordination in teams, with innovation and creativity, skills that are more directed to their insertion and adaptation in the corporate ground” [33].

The third question approaches more concretely the selfcreation of brands and other ventures from fashion designers, as well the questioning of the tools allowing designers to apply their ideas on the market as well as the role of educators [34] that is essential in the development of the tomorrow’s designers [35]. The problem of this investigation is molded around these investigation questions, articulating with four main axes: higher education, the specific skills associated with business creation, the job market and entrepreneurship.

The choice made on this thematic is linked by the fact that Portugal has lost, in the last 10 years, important positions regarding employment in the textile industry. With the most recent economic crisis, many were the segments of the textile and clothing industry that saw their exportations getting disturbed. As the fields of threads, home textiles knit clothing (a field that still represented 40% of exportations in 2013) and woven clothing are some of the fields that lost the most between 2007 and 2013. However, the issue was minimized due to good results in the technical woven sector, which shows the importance to bet on educating people and continue to develop this kind of sector among others.

The factor of internationalization developed by associations of the field or even by businesses of this industry has promoted the stability of the commercial balance with the increase of exportations from enterprises implemented in the international market. Though, the low rate of national consumerism [36] has not allowed the development of small businesses created by young designers as well as the immovability of long-lasting enterprises with a history of financial issues at a very difficult period worldwide. Nevertheless, the internationalization of businesses to new markets outside Europe has allowed the insertion of fashion designers in enterprises for the last few years, though with some fragilities regarding wages and functions attributed, creating a growth in exportations apparently stable for the last 3 years.

The choice of this thematic is also justified by the increasing role that fashion design education programs play in Portugal as well as a growing recognition of the fashion design field, nationally and internationally. In this context, many names have promoted the Portuguese fashion design scene. Although many have chosen foreign countries to improve their skills and design education, names like Marques’ Almeida (winners of the LVMH prize) or internationally renowned Filipe Oliveira Batista are some of the people changing the fashion game [37].

This thematic was also chosen with the idea of demystifying the idea of “easy employment” of the field, that many young students have when beginning their academic process, as it is vital to understand that the reality is quite different from the stereotypes produced many times by society [18]. On the other side, belonging to a generation that faces many employment challenges but also believes that an entrepreneurial and creative vision can overcome this crisis, is also the one of the reasons for the choice of such thematic [38], in a complex and challenging sector that belongs to one of the most powerful industry of the world’s economic system [39].

It is also believed that this study will help in mapping a reality that still needs to be analysed, approaching a problem of multidisciplinary content, with a logic of investigation-action, as it is important to highlight concerning the treatment of this subject.

Considering the subject and the problem of investigation of this study, the following work will observe a structure regarding these contributions:

a. to contribute to a discussion about youth employment and opportunities after graduation;

b. to reflect on entrepreneurship education and learning, considering the fashion design field in Portugal and abroad;

c. to understand the skills needed by fashion designers to create value and innovation in such a challenging industry;

d. to identify alternative models and solutions of professional development through the creation of new business and author brands;

e. to propose new solutions to promote a successful transition from formation to the job market as well as the development of new businesses in the fashion industry.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

This study starts with detailed research on fashion design higher-education curricula, as well as the specificities these courses on the matter of entrepreneurship and its approach. The study was conducted on fashion design higher-education courses in Portugal and abroad, considering The Business of Fashion’s ranking of best fashion design courses around the globe [40]. Considering this approach on fashion design courses in Portugal and abroad, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1

Fashion design higher-education programs prepare their students to think and act like entrepreneurs.

This first hypothesis considers the exploration made on fashion design higher-education programs in Portugal and abroad, and the observation made on their curricula to understand if such programs are preparing young designers to think and act like entrepreneurs inside the classroom, challenging them to know more than what they are expected to. This first hypothesis is also based on studies on fashion design studies entrepreneurship, as well as models proposed by authors [41-43].

In the meantime, these courses were also studied, this time considering the outcomes, skills and attitudes presented in each curriculum. The same higher-education courses were observed, to create a map of the professional outcomes presented, as well as the skills and attitudes considered necessary in each course. This second analysis of fashion design courses, this time focusing on vocational outcomes, skills, and attitudes, revealed the second hypothesis of the study:

H2

Young fashion designers entering the industry after a fashion design course are equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to create their own business.

The second hypothesis proposes to observe if young fashion designers are prepared for the challenges and difficulties associated with the creation of a business in a competitive and fast-moving industry, considering higher-education courses and the reality of the fashion industry. This second hypothesis is also constructed on opinions on apparel higher-education courses implications in the creation of businesses, shared by authors such as [44,18,45].

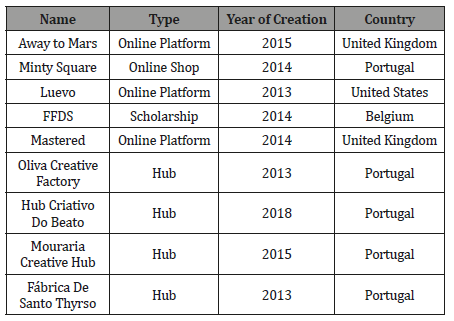

Besides approaching existing solutions such as Portugal Fashion and Moda Lisboa, this study explored new solutions that are described in the following table (Table 1):

Table 1:Explored solutions for fashion design entrepreneurs.

Concluding this review of existing incentives, platforms and hubs aiming to propose solutions for fashion design entrepreneurs, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H3

Existing incentives and solutions created to help entrepreneurs are adapted for fashion design entrepreneurs.

The third and last hypothesis aims to approach the existence of incentives for entrepreneurship, as well as other solutions created to help entrepreneurs, in order to perceive their differences as well as their level of adaptation for the specificities of fashion design entrepreneurship. This last hypothesis is also supported by recent studies and reports [46,47], as well as responses obtained through this study.

Methods

In this study, the use of a mixed-methods approach was privileged, considering the research field, as well as the implications obtained in the literature review. Moreover, the possibility to acquire results from two very different perspectives was crucial in this investigation.

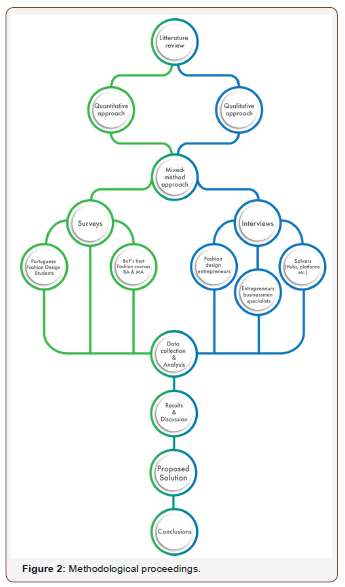

For this particular study and considering the field in which the work is inserted, the choice of methodology is directly related to design methodologies, choosing for that matter, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, as both can explore the data needed in a multidisciplinary field. To clarify the all process of investigation since its beginning, a figure was made (Figure 2).

Each phase of the investigation is presented, separating the first phase of investigation previously shown in the project, before the actual thesis, and the second phase of the investigation, given in this study. Based on the literature review, the choice of a mixedmethods approach was made, reflecting both sides of the problem [48,49,25].

As previously explained, a mixed methodology was used in this study to approach both sides of the problem. The first approach with secondary data analysis was made, as a detailed research was built on fashion design course curricula in Portugal and abroad, studying a total of nine Portuguese higher education courses, and ten international institutions.

As the quantitative research focused on students and former students of fashion design courses through the use of surveys, two different groups were observed: the first one focuses on Portuguese fashion courses and the second explores international fashion courses.

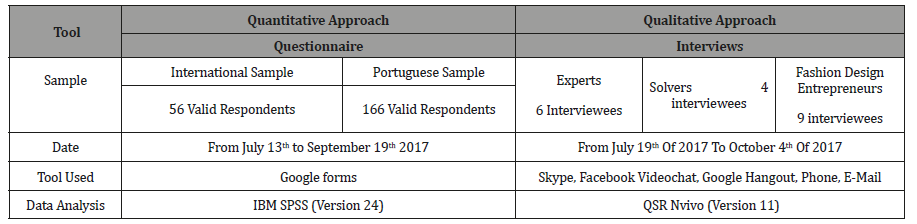

Passing on to the qualitative approach, interviews were held, focusing on three main groups: “fashion design entrepreneurs” from Portugal and abroad, “experts” and professionals of the fashion industry as well as entrepreneurs of the field and finally, a group of “solvers”, creators or contributors to existing solutions aiming to help fashion design entrepreneurs. Data collection and its analysis will lead to results, answer research questions to conclude this study with the proposition of a solution for fashion design entrepreneurs, based on the results obtained through this study (Table 2).

Table 2:Representation of the mixed-methods approach (based on primary data analysis).

Data Analysis and Discussion of Results

Starting with the quantitative analysis of this study, data obtained among fashion design students and former students highlight the need for courses to improve their curricula regarding entrepreneurship, as a majority of respondents declared the necessity to develop their knowledge on this topic [50].

Respondents also declared a need for higher-education fashion design courses to improve the follow-up of students, their access to the job market, as well as hubs and incentives, also demanding a better access to the creation of fashion ventures, as well as entrepreneurship education specific for fashion design. Students also declared their unpreparedness for the job market and agreed on the need for fashion design courses to stay close to the industry, in order to be updated to its fast-paced changes. Finally, respondents also highlighted the importance of the creation of platforms for fashion design entrepreneurs.

Passing on to the qualitative analysis, 14 different sources considered fashion design graduated not prepared for the reality of the industry, as well as the creation fashion businesses in general, rejecting H2 in the sense that young fashion designers entering the industry after a fashion design course are not equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to create their own business.

Continuing in that line, results regarding the preparation for entrepreneurial activities of higher-education fashion courses as 12 different sources for a total of 25 references stated that the training was not sufficient, also considering that other interviewees hardly mad any declaration on this subject at all in comparison. Nevertheless, these results reject H1 in the sense that fashion design higher-education programs do not prepare their students to think and act like entrepreneurs sufficiently, a statement also going in the same direction as the observation made through the quantitative data obtained.

Concerning the existing solutions at the service of fashion design entrepreneurs, the opinions on whether or not these solutions are adapted to the specificities of fashion design businesses, as 7 sources agreed with their adaptation, against 10 sources disagreeing, however, it can also be observed that among the fashion designer entrepreneurs group, the majority declared that such solutions were not adapted, rejecting H3 in the sense that existing incentives and solutions created to help entrepreneurs are not adapted for fashion design entrepreneurs, an idea also highlighted by the quantitative data.

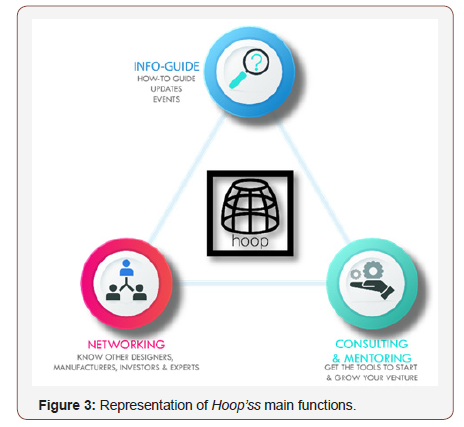

A digital platform was also proposed as a solution, to complement this study and answer to the issues detected through the research. The solution proposed is a fashion design entrepreneurship platform called “hoop”. The platform’s main options were obtained through the qualitative analysis, as interviewees were asked to reflect on the most needed solutions that should be provided on such platform. The results are presented in the following figure (Figure 3):

Considering the results obtained and explored in the previous part, the following functions are being considered for this model are represented in figure 3. The functionalities obtained with the qualitative data were reduced to three main purposes:

The first mission is to inform the visitors by providing updated information on upcoming events such as contests and forthcoming awards, conferences, scholarships, new incentives, as well as fashion events such as Portugal Fashion, Moda Lisboa, etc. The platform will also provide specific information that could be useful for fashion design entrepreneurs, such as entrepreneurship workshops and conferences, crash courses and online courses, as well as entrepreneurship gatherings and other events that were approached during the interviews process. This first functionality will also provide a “how-to guide”, with tips and tricks that are frequently asked on several topics such as intellectual propriety, legal matters, incentives, contests, etc.

The second purpose is to provide networking possibilities for fashion designers in need of new contacts, specific profiles, as well as to introduce interesting professionals to each other, always respecting a collaborative logic, as well as using other professional networking platforms such as Linkedin.

The third purpose will explore a consulting and virtual mentoring space, where professionals will share their issues and doubts to obtain the right tools and guidelines to overcome a specific phase or problem.

The platform appears as an innovative solution for fashion design entrepreneurs, entirely based on their needs and expectations, as well as recurrent problems detected, in order to present a complete solution for the industry. As this study approached fashion design entrepreneurship, considering various experiences and points of view, the platform aims to solve the main issues detected through this research.

The pre-launch version of the platform is available online for consideration at the following link: www.hoop-portugal.com

Conclusion

As the main objective of this investigation was to comprehend entrepreneurship as a potential solution for young fashion designers, entrepreneurship education was also approached in the higher education environment, to contextualize the skills and knowledge gained by emerging fashion designers during their education.

Furthermore, by exploring entrepreneurship in the fashion design field, this study aimed firstly, to clarify if fashion design higher education programs are prepared for the new challenges of a society always more directed to entrepreneurship. Secondly, to understand what specific skills and attitudes young fashion designers lack when it comes to creating their venture in the industry. Thirdly, an exploration of existing solutions aiming to help fashion design entrepreneurs was made, as well as a search for qualities and functions that could be game-changing for fashion design entrepreneurs.

Since definitions on entrepreneurship are still different from author to author, this study highlighted the fact that not every fashion design entrepreneur wants to start their brand, as entrepreneurship is a state of mind, a motivation, and an attitude. Through the literature review, this study also related entrepreneurship with the will to design, create and innovate. The fashion designer of tomorrow will have to reunite the skills that any fashion designer is supposed to have after graduation but also attending to the needs of the society and the ever-changing character of it, the fashion designer will have to possibility to be much more than a creator, as its pro-active character and entrepreneur mindset will be more than ever, tools to make the difference. Fashion designers should always think in terms of value, the importance to create higher value for people, to improve their lives and their everyday moves through garments, once again, a correlation between entrepreneurship and apparel design [50,51].

With the use of secondary sources to collect data on fashion design higher education programs around the world and in Portugal, this study was able to encounter a lack of entrepreneurship education applied to fashion. Moreover, the data collected from surveys revealed that students and former students of fashion design courses feel a real need to learn how to work, think and act like entrepreneurs, in a field as challenging as the fashion industry, considering the fact that most respondents declared their lack of entrepreneurial skills and knowledge, and acknowledged the high importance of entrepreneurship for fashion design courses. These results also were confronted with the curricula presented by the courses observed, as the skills and future outcomes displayed by these fashion design institutions reflected this gap. Therefore, it can be concluded that fashion design higher-education courses are still not prepared for the new challenges of a society always more directed to entrepreneurship, answering the first research question.

These courses must have a base to create the foundations of the program, and also attend to all the characteristics involved, such as the level of education, the type of course in which entrepreneurship is taught, the teachers involved in the program as well as the activities proposed to students [22].

As it was observed throughout the results, it is crucial that young designers develop contact and ability to find external resources as soon as possible. For that, it is critical to educate these future professionals in the classroom, as institutions should be linked directly to the industry and show their students this connection, which would also turn it easier to connect with enterprises through partnerships, internships or other activities outside the classroom, involving the students as well as the educators. It is also highly relevant to keep in mind the important differences between generations, as there is an existing gap between educators and students, which can be translated to misconceptions of the fashion design course itself and the expectations that students have when entering a fashion design program compared to what is expected of them by their educators [29].

As a result, data obtained in the surveys also showed that students and former students estimated that their courses had not prepared them correctly for the job market. Moreover, designers already working on the market and experts find a lack of knowledge, as well as general financial difficulties, issues concerning sourcing and production for small quantities in early stages, as well as challenges in production, marketing, and development of small businesses.

Some referred the option for a master’s degree was related with the potentiality to create a business in the future, as it is considered a crucial part of education, a conclusion also made by author Alexandra [8].

It is consensual that entrepreneurship should be a part of education programs as a way to think and act, however, it could be proposed as an actual discipline for students in an optional choice.

The evident issues of teaching parties in fashion design courses can be related to the actual lack of entrepreneurs inside these courses, who could become motors for these higher education programs, as opposed to other educational systems or private institutions that facilitate the access of teaching positions to people directly related to a specific market. For higher-education institutions, the lack of connection with the industry could also be one of the causes of this issue. The creation of partnerships with enterprises, retail brands, and fashion designers could beneficiate all parties and create new ventures, as well as motivate these young designers to develop their own business in the future.

As the industry deals with daily challenges such as competition, globalization, marketing, innovation or sustainability, young fashion designers are pushed into an ever-evolving machine, where being creative is only part of the solution, as globalization is crucial to understand this ever-changing field. Innovation is key for the future of fashion as it is vital to the future of entrepreneurship, as well as intrapreneurship as it was previously seen in the ITV field research. So-called “intrapreneurs” are no more than entrepreneurial mindsets who work for other parties [18]. Therefore, it is more than ever crucial to develop the minds of fashion design students for the use of these skills and make them understand that entrepreneurship is not only about creating their brand but also how to be successful, innovative and forward-thinking as a contributor of the fashion industry [44]. As a result, it can also be concluded that young fashion designers lack entrepreneurial skills and attitudes, which could benefit them in the creation of their project, as well as working for other parties, responding to the second research question.

As this study is coming to an end, Portuguese universities are once again gaining more students. It is imperative for fashion design courses to develop solutions to grow awareness among their students of the difficulties and solutions that come in the way of entrepreneurs as students continue to be lured into courses promising them a career as entrepreneurs, even if entrepreneurship is not part of the curricula nor is it taught as a way to think. It is therefore imperative for higher education to define the grounds on which fashion design courses must operate in the future.

Fashion design entrepreneurship is still a recent topic investigation-wise, meaning that the scientific community of the field must investigate further on this multidisciplinary subject. This study has evidenced the need for fashion design courses to re-adapt their curricula, considering this new paradigm in the industry.

This need for entrepreneurial contents in fashion design courses also translates itself years after, for fashion designers who strive in beginning their venture, as evidenced during the interview process, whether in Portugal or abroad, as many professionals stated that there is an evident lack of entrepreneurial contents in fashion design courses, a lack of information that could have benefitted them when starting their brand or project, a gap also highly evidenced by the quantitative data obtained in the surveys.

Moreover, this study has established the need for incentives and platforms specially directed to fashion design ventures, as global associations for entrepreneurs cannot always help the specificities experienced in the fashion industry. On the other side, alreadyexisting physical platforms like Moda Lisboa or Portugal Fashion can only help emerging designers to project their collections for a limited time and cannot help fashion design entrepreneurs on specific matters like IP, funding, administrative processes, etc., a reality highly evidenced by the qualitative data collected during the interviews.

Therefore, based on both qualitative and quantitative data resulting from interviews and surveys, a solution was proposed to fill the gap evidenced by this study. The study also explored existing solutions in Portugal and abroad, that intend to help fashion design entrepreneurs in different ways. These investigated solutions were also part of the third research question and evidenced the lack of information available for fashion design entrepreneurs starting a new venture was blatant and therefore, the proposed model, hoop, is a first draft of what could become the missing link for these emerging fashion ventures. This study also gained precise information through the data collected interviews, that are the base for the platform, as its design and functionalities followed an accurate process, obtained through encoding.

The creation of hoop is not only beneficial for fashion design entrepreneurs as an informative tool, it can also contribute to the discussion on fashion design entrepreneurship and create a safe setting for the future of this field, by building a participative and collaborative network of professionals, willing to change the fashion design industry into a more positive and sustainable environment, by giving information and providing opportunities to emerging fashion designers ready to create value through fashion design.

Limitations and Future Recommendations

The limitations associated with this study are related to the need to improve further this investigation. It is important to remind the fact that a real the present study came from a real lack of information on fashion design entrepreneurs, as the study of this topic is still very recent. The improvement of scientific investigation on fashion design entrepreneurship is therefore crucial.

Another matter was related to the application of interviews and surveys. For the interview process, a long list of people was contacted, but very few responded to the first contact made, however, this is only part of the difficulties encountered when applying interviews, as the interviewer always depends on the will of others. Future investigations could apply a similar model in other countries to add complementary results.

It also seems very important to introduce the data obtained in this study and continue to add more data in the future, by keeping contact with the people interviewed and inquired to get an evolution of the results in the next few years. To increase the level of data to be obtained in the future, a document was created to keep track of the alumni inquired during the inquiring process, as well as another record for every person interviewed during that time, as keeping data from alumni for the next 10 years would definitely be an essential part of potential future research in order to understand the extent of results produced by fashion design programs [33].

Moreover, it is crucial for this field to develop into other studies and programs, linking education, industry professionals, and market experts and see how this network can evolve in the future, as well as creating new ventures, new projects and the opportunity for interesting studies to make.

An important part of this study resided in comprehending how can young fashion designers be encouraged to become entrepreneurs, as this study also pointed out the lack of entrepreneurial curricula among fashion design courses. Following this logic, further studies on this topic should focus on this breach and propose an entrepreneurial model to be applied and tested in fashion design courses and observe the differences among the alumni after a few years.

Considering the growing amount of studies focusing on this multidisciplinary topic, as well as the new solutions appearing each day on the market to facilitate entrepreneurship in fashion design, reviewing this state of the art in a few years will be very interesting. As fashion design will continue to grow, new technologies will appear, innovation-driven solutions will appear on the market to create new paradigms of fashion entrepreneurship.

The solution proposed will also have to be revised in the future, considering the changes and new technologies to come, as well as specific needs and issues for the fashion design entrepreneurs of tomorrow. As the platform is under construction and needs further testing, visitors are welcome to send their opinion on the initiative. The goal is also to protect the brand, as the register is currently in process.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- ANJE (2017) Associação Nacional de Jovens Empresários.

- Agis D, Vaz P, Dinis AP (2014) Plano estratégico têxtil 2020: projetar o desenvolvimento da fileira têxtil e vestuário até 2020. ATP-Associação Têxtil e Vestuário de Portugal, Vila Nova de Famalicão.

- (2016) Estatísticas do Concurso Nacional de Acesso de 2016: comparação por curso, Lisbon, Portugal.

- (2010) Estatísticas do Concurso Nacional de Acesso de 2010: comparação por curso.

- (2017) IAPMEI 2017.

- European Commission (2008) Entrepreneurship in higher education, especially within non-business studies. Final Report of the Expert Group.

- Vieira DA, Marques AP (2014) Preparados para trabalhar?

- Mwasalwiba E (2012) Entrepreneurship education: a review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. education + Training 40(2): 72–94.

- European Commission (2008) Entrepreneurship in higher education, especially within non-business studies. Final Report of the Expert Group.

- European Commission (2013) Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan Reigniting the entrepreneurial spirit in Europe. COM (2012) 795 final.

- (2016) Uma nova imagem para an ITV.

- (2017) Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2017) Global Report 2016/2017.

- Caetano E (2017) Portugal com a segunda maior queda da taxa de desemprego na zona euro. Observador. Lisbon, Portugal.

- Eurostat (2017) Têxtil: um setor que anda mais depressa do que o país. Economia Online. Lisbon, Portugal.

- de Sousa JF (2017) Desemprego jovem: um flagelo a combater. Diário de Notícias.

- Friedman T (2013) Need a Job? Invent It. The New York Times. New York City, USA.

- Runco MA (2007) Creativity Theories and themes: Research, development, and practice. Academic Press. Schiemann M (2006) SMEs and entrepreneurship in the EU. EUROSTAT report.

- Sousa G (2015) Empreendedorismo e(m) Design de Moda: uma visão estratégica para o Ensino Superior. [Online]. Thesis Project from the Architecture Faculty of the University of Lisbon, Portugal.

- Correia Santos SH (2013) Early stages in the entrepreneurship nexus: Business opportunities and individual characteristics. Instituto Universitário de Lisboa.

- Knight FH (1921) Risk, uncertainty and profit. New York City: NY: Hougthon Mifflin, USA.

- Schumpeter JA (1949) “Economic theory and entrepreneurial history”, in Wohl, RR, Change and the entrepreneur: postulates and the patterns for entrepreneurial history, Research Centre in Entrepreneurial History, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, USA.

- Kirzner IM (1973) Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, USA.

- Drucker PF, Noel JL (1993) Innovation and entrepreneurship: Practices and principles. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 34(1): 22- 23.Hisrich RD (1990) Entrepreneurship / Intrapreneurship. American Psychologist 45(2): 209–222.

- Hisrich RD (1990) Entrepreneurship / Intrapreneurship. American Psychologist 45(2): 209–222.

- Coutinho CP (2015) Metodologia de investigação em ciências sociais humanas: teoria e prática. Coimbra: (Edt) Almedina, p. 412.

- Moreira Da Silva F (2010) Investigar em design versus investigar pela prática do design– um novo desafio científico. INGEPRO– Inovação, Gestão e Produção 2(4): 82-91.

- On n’est pas couché (2016) Olivier Rousteing on n’est pas couché.

- Tseëlon E (2010) Outlining a fashion studies project. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty 1(1): 3–53.

- Kawamura Y (2011) Doing Research in Fashion and Dress. An Introduction to Qualitative Methods. (1st edn) Oxford, Berg, United Kingdom.

- Silva S (2017) Há sete anos que não entravam tantos alunos no ensino superior. Público.

- Caetano E (2017) Portugal com a segunda maior queda da taxa de desemprego na zona euro. Observador. Lisbon, Portugal.

- Cruchinho A (2009) Design - A Construção Contínua de Competências. Tese de Doutoramento em engenheira Têxtil, Escola de Engenheira da Universidade do Minho, Portugal.

- Aspers P (2009) Using design for upgrading in the fashion industry. Journal of Economic Geography 10(2): 189-207.

- Kozar JM, Connell KH (2013) The Millennial graduate student: implications for educators in the fashion discipline. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 6(3): 149-159.

- Manzini E (2011) Design schools as agents of (sustainable) change: A Design Labs Network for an Open Design Program.

- Beard ND (2008) The branding of ethical fashion and the consumer: A luxury niche or mass-market reality? Fashion Theory - Journal of Dress Body and Culture 12(4): 447-468.

- Clark H (2008) SLOW + FASHION — an Oxymoron — or a Promise for the future? Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body and Culture 12(4): 427-446.

- Runco MA (2007) Creativity Theories and themes: Research, development, and practice. Academic Press. Schiemann M (2006) SMEs and entrepreneurship in the EU. EUROSTAT report.

- Teodoro JO (2013) O Ensino do Design de Moda em Portugal: Contribuição para uma Análise Crítica da Educação para a Sustentabilidade. Faculty of Arts from the University of Lisbon, Portugal.

- The Business of Fashion (2015) Do You Really Want to Start a Fashion Business?

- Nielsen SL, Stovang P (2013) DesUni: university entrepreneurship education through design thinking. Education + Training 57(8): 977- 991.

- Kurz E (2010) Analysis on fashion design entrepreneurship: challenges and supporting models. Master’s dissertation of Science in Fashion Management. University of Borås, Sweden.

- Cruchinho A (2009) Design - A Construção Contínua de Competências. Tese de Doutoramento em engenheira Têxtil, Escola de Engenheira da Universidade do Minho, Portugal.

- Mills CE (2012) Navigating the interface between design education and fashion business start‐up. Education + Training, 54(8/9): 761–777.

- Hodges N, Watchravesringkan K, Yurchisin J, Karpova E, Marcketti S, et al. (2016) An exploration of success factors from the perspective of global apparel entrepreneurs and small business owners: Implications for apparel programmes in higher education. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 9(1): 71–81.

- (2017) IAPMEI 2017.

- Wenting R (2008) Spinoff dynamics and the spatial formation of the fashion design industry, 1858-2005. Journal of Economic Geography 8(5): 593–614.

- Morgan DL (2007) Paradigms Lost and Pragmatism Regained: Methodological Implications of Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1(1): 48–76.

- Holloway I, Wheeler S (2009) The nature and utility of qualitative research. In Introduction to Qualitative Research: Initial Stages, pp. pp. 3-20.

- Segonds F, Mantelet F, Maranzana N, Gaillard S (2014) Early stages of apparel design: how to define collaborative needs for PLM and fashion? International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 7(2): 1-10.

- Silva S (2017) Há sete anos que não entravam tantos alunos no ensino superior. Público.

-

Clara Eloise Fernandes. Fashion Design Entrepreneurship: Skills and Solutions to Create a Fashion Business. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 3(1): 2019. JTSFT.MS.ID.000533.

-

Fashion Design, Entrepreneurship, Design, Linear regression, Creative arts

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.