Mini Review

Mini Review

Effects of Pattern Maker’s Work Experience with Designer on Clothing Creation

Umer Hameed1*, SaimaUmer2 and Usman Hameed2

1National Textile University, Pakistan

2Punjab University Lahore, Pakistan

Umer Hameed, National Textile University, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Received Date: September 05, 2020; Published Date: October 07, 2020

Abstract

The effects of a patternmaker’s prior experience working with a designer on their patternmaking was investigated by comparing two patternmakers’ (P1 and P2) work processes. P1 had considerable experience working with the designer involved, while P2 had none. We asked both patternmakers to make patterns for two garments and observed their work processes. We compared the results after their first and second session working with the designer. P1 had a high level of understanding of the design and required less verification of points by the designer. Few modifications were required. Conversely, P2 asked the designer more questions and the designer requested more modifications following the toile check. However, P2 required less points confirmed by the designer following the second session compared with the first session. It was shown that greater experience working with a designer enabled a patternmaker to obtain a better understanding of the designer’s intention in a design. Thus, the patternmaker was able to make a pattern that satisfied the designer’s requirements more quickly and with fewer modifications. This finding increases our understanding of the effects of interactions between designers and patternmakers on efficient garment design.

Keywords: Patternmaker; Creation; Experience; Designer; Garment

Introduction

A patternmaker constructs a three-dimensional garment from a two-dimensional illustration. During the patternmaking process, there are many interactions between a designer and a patternmaker to create a beautiful and comfortable garment [1,2]. The gathering and processing of information between designers and patternmakers is important to enable efficient fashion creation and manufacturing [3].

We have been investigating the effects of patternmakers’ work processes on clothing design [4]. A proficient patternmaker was able to identify potential problems and then consider possible solutions to those problems. We also investigated the effect of a patternmaker’s proficiency on garment creation. We asked two patternmakers to make two patterns from the same design and compared the patternmaking processes and the resulting manufactured garments [5].

Although a designer tries to describe their intentions in a design brief, this information is not enough, especially in the creation stage. More detailed specifications are developed through interactions with the patternmaker. However, the contents of those interactions and their effect on the patternmaker’s proficiency are unclear.

Therefore, in the present study, the effects of a patternmaker’s experience working with a designer on garment design was investigated. We employed two expert patternmakers who had different levels of experience working with a designer. By comparing the interactions during the patternmakers’ work processes between their first and second session working with the designer, we investigated how patternmakers are able to improve their understanding of a designer’s intention and the efficiency of garment design.

Experimental Method

To investigate the influence of a patternmaker’s experience working with a designer on their patternmaking, one designer and two patternmakers, P1 and P2, were employed. The designer has more than 15 years of experience and manages a self-brand in France. The patternmakers have different levels of experience working with this designer. P1 has 13 years of experience working in France and has worked with the designer many times. P2 has worked in Japan and the United States for more than 20 years but has had no experience working with this designer.

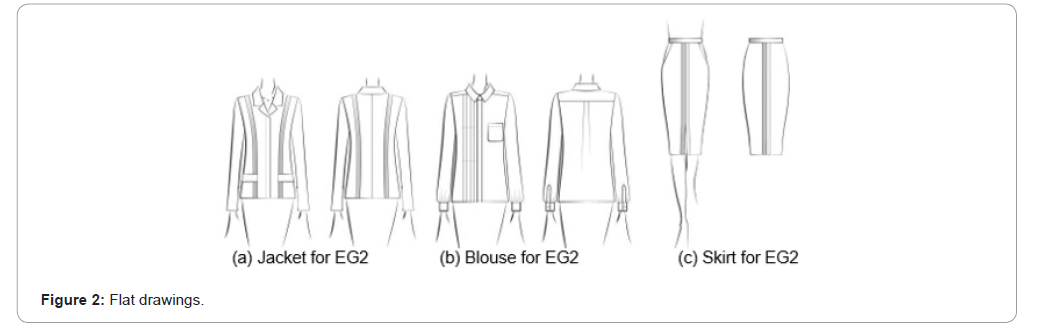

The designer designed two sets of garments for a luxury maison in France, named EG1 and EG2. EG1 consists of a jacket and a skirt and was used in a previous study [5]. EG2 consists of a jacket, a blouse, and a skirt. She was also asked to select the textiles for the garments. Figures 1 and 2 show illustrations and flat drawings for EG2. The illustrations, flat drawings, and swatches of the fabrics that the designer selected were presented to the patternmakers. In addition, French size 38 (bust 87cm, waist 68cm, hip 93cm) was specified. First, the patternmakers were asked to make patterns for EG1. This was the first time P2 had worked with this designer. After the patterns for EG1 had been made and the samples had been approved by the designer, we asked the patternmakers to make patterns for EG2. We investigated the patternmaking method and the interactions between the patternmakers and the designer by listening to and observing them while they worked. The differences between the patternmaking processes and their interactions with the designer while making patterns for EG1 and EG2 were examined.

In this study, the patternmaking processes used for EG2 were compared with those used for EG1. The patternmakers made each pattern based on the conditions specified. After the patterns had been made, the patternmakers checked a toile and modified it. Following these modifications, the designer checked the toiles. The designer only needed to check P1’s toile once. However, the designer checked P2’s toile twice because further modifications were required. The first check was undertaken using e-mail and photos of the toiles, and the designer inspected P2’s actual toile the second time. We recorded the designer’s opinions regarding the toiles.

Work Process of Patternmakers

Information recognition

We questioned them regarding the points they confirmed and the decisions they made before starting to make the pattern. Their replies were as follows.

Confirmed points and decisions of P1: P1 confirmed the textiles and the size specifications for each garment design. Measurements were set according to the sizes specified and the proportions shown in the flat drawings. Dimensions such as skirt length and jacket shoulder width of EG2 were set to the sizes specified in EG1. Although the sleeve of the jacket was shown as a one-piece sleeve on the drawing, P1 decided to make a two-piece sleeve because this made it easier to create the desired silhouette.

Confirmed points and decisions of P2: P2 set the measurements for EG2 based on the sizes and design of EG1. P2 wanted to ask the designer whether the sleeve was intended to be a one-piece sleeve or a two-piece sleeve, but the designer was unavailable, so for convenience we instructed P2 to use her discretion. She decided to make a two-piece sleeve for the same reason as that cited by P1.

Patternmaking

P1: In the patternmaking process, P1 used a basic pattern that has been used previously and drafted it by hand. P1 set the sizes by taking into account the flat drawings and the proportions on them. Fabric properties were not considered because P1 thought that this was the responsibility of the sewing division of the atelier in France.

P2: P2 used patterns that had been made in the past. For EG1, P2 noticed that the designer gave higher priority to the feeling and silhouette of the illustration than the flat drawings. Thus, she also gave higher priority to the illustration. The model height was not specified by the designer, thus P2 set the back length of the jacket based on a model height of 158cm, which is the average height of Japanese women in their twenties. However, for EG2, P2 set this measurement at 167cm because she heard the designer mention that the average height of French women is 167cm while the designer was checking the toile for EG1. P2 commented that it took less time to understand the designer’s intentions for EG2 than for EG1. The details of the patternmaking process for each item are as follows.

a) Jacket

P2 recognized that the feeling conveyed by the illustration for the jacket was straight and stylish. For EG1, the designer emphasized the feeling of the illustration. Thus, P2 also emphasized the feeling of the illustration. The width of the narrow panels in the bodice was set to 3cm, taking into account the fabric pattern and the illustration. The same shoulder pads used in EG1 were used in EG2 because they were approved by the designer. The sleeves and armholes used in EG1 were also used with some modifications to sizes.

b) Skirt

A basic pattern for a tight skirt was used. The length used for EG1 was also used for EG2 because it was approved by the designer. In addition, P2 considered the fabric properties. Although the fastener was positioned at the side in the illustration, it was changed to the center of the back after taking into account the sewing and seam allowance because P2 expected that the designer would approve the change if the desired silhouette was retained.

c) Blouse

P2 noticed differences between the flat drawings and the illustration. In the flat drawings, the outside curve of the collar was round and set away from the neck to look like a blouse. However, the illustration showed a linear collar line that looked more like a shirt. Because the designer gave priority to the illustration for EG1, P2 followed the illustration for EG2. The armhole line was drawn based on her previous experience. Because this was the first time P2 had made a pattern for a blouse by this designer, it took more time to set the size and silhouette for the blouse than for the jacket.

Toilet checking and modification

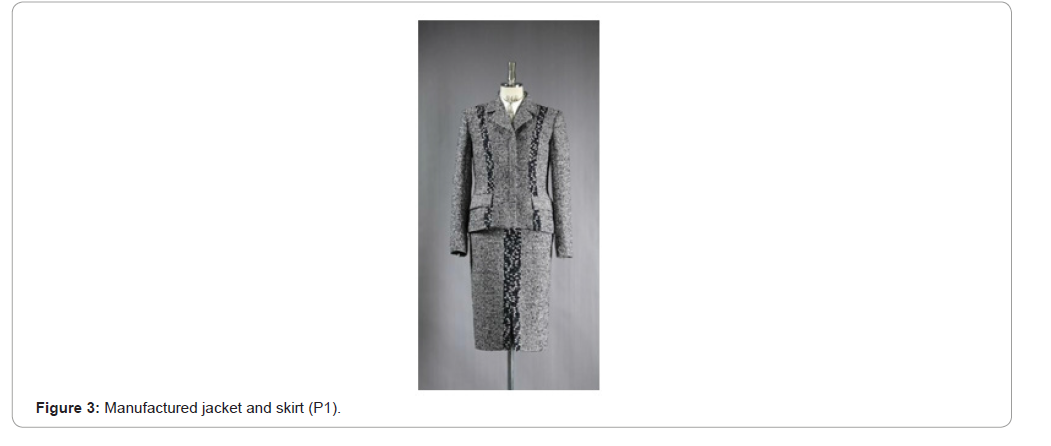

P1: The designer decided that the jacket did not need any modification. For the skirt, the designer instructed P1 to increase the width and reduce the length. For the blouse, the designer asked P1 to add one more pleat. Figure 3 shows the manufactured garments.

P2 – the first check: The designer checked P2’s toile twice. The first time, this was done by photos sent via e- mail. P2 asked the designer questions and obtained responses by e-mail. The questions and responses are as follows.

a) Jacket P2 informed the designer about details such as the fly front and a stitch because P2 had used her discretion in relation to these issues. In addition, P2 also informed the designer that she had made a two-piece sleeve with a slit opening. The designer replied that the cuffs required a concealed fastener. In addition, she asked P2 to lower the return point of the lapel, and P2 made this modification. Regarding the sleeves, P2 thought that the sleeve silhouette would be too narrow if a concealed fastener was attached. Thus, P2 increased the width of the cuffs to make a silhouette closer to that shown in the illustration, even though the designer had provided no instruction on cuff width.

b) Skirt P2 informed the designer that she had inserted waist darts because it was a tight skirt. P2 also informed the designer that the width of the narrow panel of the skirt was the same as that of the jacket and that the fastener was set at the center of the back. Regarding the fastener position, the designer asked P2 to check for seam slippage because it was a thin tweed fabric. After testing, P2 confirmed that there was slippage of the fabric. Thus, P2 suggested bonding interlining, which the designer approved. P2 modified the patterns as instructed.

c) Blouse P2 informed the designer about the placement of the top button, the front fly, the edge stitch on the yoke, and the three-winding of 1cm at the hem. The designer instructed P2 to reduce the width of the sleeves, to add one pleat, to narrow the cuff width a little, to lower the position of the pocket a little, and to shorten the length of the blouse a little. P2 modified the pattern as instructed. Compared with the jacket and the skirt, there were many alterations requested.

P2 – the second check: The second time, the designer checked the actual toile while a model was wearing it. The designer instructed P2 to increase the size of the jacket armhole while retaining the same shape. The designer also instructed P2 to increase the width of the jacket sleeve and to reinstate the previous cuff silhouette. P2 modified the pattern as instructed. The final garments are shown in Figure 4.

Effect of Prior Interactions on Garment Design

P1, who had considerable prior experience working with the designer, was able to recognize the features of the designer’s illustrations. When the designer checked the toiles, less modifications were required for P1’s patterns than for those of P2. The modifications that were requested mainly related to minor details.

P2 needed more time for patternmaking on EG1 than on EG2. Based on the interview with P2, the design features obtained from the illustration and flat drawings for EG1 did not accurately reflect the designer’s intentions, and it took more time to set the vertical dimensions such as the back and sleeve length. Moreover, the designer’s preferences and points of consideration for a garment were not well understood.

In the case of the jacket and skirt for EG2, it was possible to understand the designer’s intentions from the illustration and the flat drawings. The time required to set the dimensions was less than that for EG1 because the same dimensions could be repeated. In addition, the armhole and sleeve patterns the designer approved for EG1 were able to be used with minimal modification, which reduced the time required. However, there were numerous requests for modifications to the blouse pattern because P2 had no previous experience working on a blouse by this designer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it was shown that increased interaction between a patternmaker and a designer made it possible for the patternmaker to more clearly understand the designer’s intentions from the design illustration. Having access to patterns retained from previous experiences working with a designer also improved the efficiency of patternmaking. Thus, a patternmaker who had extensive prior experience working with a designer was able to make a pattern that satisfied the designer quickly and accurately. In addition, the nature of the interactions between the patternmaker and the designer were clarified by this study. Experience working with a designer reduces a patternmaker’s need to proceed by trial and error. This finding will improve our understanding of the effects of interactions between designers and patternmakers on efficient garment design.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- LaBat KL, Sokolowski SL (1999) A three-stage design process applied to an industry- university textile product design project. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 17(1): 11-20.

- McKinney EC, Bye E, LaBat K (2012) Building patternmaking theory: a case study of published patternmaking practices for pants. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 5(3): 153-167.

- Rissanen T (2007) Types of fashion design and patternmaking practice. University of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Kim KO, Takatera M, Otani T (2014) Effect of a Patternmaker’s Proficiency on Clothing Production. Global Fashion Conference, Ghent, Belgium.

- Kim KO, Takatera M, Otani T (2016) Effect of patternmaker's proficiency on the creation of clothing. Autex Research Journal.

-

Umer Hameed, SaimaUmer, Usman Hameed. Effects of Pattern Maker’s Work Experience with Designer on Clothing Creation. 7(1): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000651.

-

Patternmaker, Creation, Experience, Designer; Garment

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.