Research Article

Research Article

Healthy Lifestyle of Fare Collectors and Bus Drivers in Akure, Nigeria

Adeniran Adetayo Olaniyi1*, Ilugbami Joseph Olanrewaju2, Fakunle Olutayo Sunday3 and Tayo Ladega Oluwadamisi4

1Department of Logistics and Transport Technology, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria

2Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo-Rector’s Office, Nigeria

3Department of Sociology, Redeemers University Ede, Nigeria

4University of Bangor, United Kingdom

Adeniran Adetayo Olaniyi, Department of Logistics and Transport Technology, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria.

Received Date: February 06, 2023; Published Date: February 10, 2023

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to delve into the healthy lifestyle of public fare collectors and bus drivers in Akure, Nigeria. A cross-sectional study of 33 bus drivers and 33 fare collectors from the bus terminal situated in FUTA North gate, Cathedral, Ilesa garage, Benin garage, and Old garage was quantitatively analyzed. Anamnesis and the Individual Lifestyle Profile (ILP) questionnaire were used to establish the scores for nutrition, preventive behaviour, stress control, and social relationship. Quantitative data collection emanates from 1st October to 31st October 2022. The confidence level adopted for this study was 95% (p≤0.05), and chi-square was employed for data analysis. The study found that there was a significant difference (p>0.001) between fare collectors and bus drivers for a time in the transport union (11.7±5.53; 5.24±4.45 years), time on the job (9.36±7.42; 5.03±4.35 years) and age (41.46±7.46; 32.41±7.77 years). The study also found that there were no associations between the answers regarding the job (p>0.05). Concerning the four ILPs, the fare collectors and bus drivers presented negative behaviour for nutrition (p=0.79), preventive behaviour (p=0.08), stress control (p=0.87), and social relationships (p=0.56) with no associations between groups. In conclusion, it was discovered that there were associations between time on the job and age, but there was no association in the healthy lifestyle as regards the comparison of fare collectors and bus drivers. Finally, public fare collectors and bus drivers have a negative lifestyle profile regarding nutrition.

Keywords:Health Promotion; Life Style; Public Bus Drivers; Fare Collectors

Introduction

The term “lifestyle” refers to a collection of habits that represent certain values, behaviours, and possibilities in people’s lives [1]. An ideal lifestyle includes good eating practices, frequent exercise, preventative healthcare, and other elements that increase life expectancy and promote healthy aging [2]. Long work hours, poor posture, inactivity, unhealthy eating habits, shift work, and changes in the circadian cycle all contribute to a lifestyle that is known to be negatively correlated with wellbeing. These factors also increase the risk of obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperleptinemia, hepatic steatosis, hyperglycemia, and hypoinsulinemia [3]. Given the length of time employees spend there, the workplace has to offer regular health routines to encourage a healthier way of life.

According to worldwide research (32% on average) and domestic studies (24% on average), there is a significant incidence of obesity among those who work in public transportation (Souza, Assunço, and Pimenta, 2019) [4]. According to Assunço and Medeiros [5], Moura, Netoand, and Silva [6], and Battiston, Cruz, and Hoffmann [7], this may be connected to high levels of psychological stress being exposed to. Drivers and bus collectors have been classified as a high-risk category for health concerns due to stressful working circumstances, long hours spent sitting, and other factors connected to their jobs [8,9]. Due to the collective duty of their activity: everyday passenger transportation, these professionals are an exceptionally essential occupational group, especially in the most urbanized cultures [7,8,9].

To avoid accidents, being a bus driver needs continual attention and driving skills: accuracy, self-control, quick response time, and the ability to comprehend the surrounding environment [6]. In addition, the onboard fare collector’s job is to support the bus driver during the course of his shift [10]. They develop musculoskeletal ailments and occupational diseases as a result of prolonged exposure to stressful situations [11,12]. Several studies in this area examine various viewpoints, such as aggression against drivers, health, and working circumstances [4, 6,7], cardiovascular risk-taking into account race [9] or workday [10], the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain [11], food and anthropometric profile [13], physiological aspects, for example, heart rate fluctuation [14], the risk associated with work-related injuries [15], metabolic and urinary profile [16] or stress [17].

The significance of the studies mentioned above in terms of the various perspectives is undeniable; however, in order to better understand these professionals, it is necessary to look into the various lifestyle perspectives. This is because people’s attitudes and values, which are directly related to their quality of life, are influenced by a set of habits and lifestyle choices that have only been partially discussed in previous studies (Nahas, Barros and Francalacci, 2019). As a result, the more knowledge that is known about the variables that affect these professionals’ lifestyles, the more knowledge is available to provide these employees with health promotion measures [18]. The methods for creating safe and healthy environments in the workplace continue to evolve as a result of ongoing activities [19]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the health pattern of bus drivers and fare collectors in Akure, Nigeria.

Methods

This study adopted a cross-sectional research design and a quantitative strategy. Data collected from 33 bus drivers and 33 fare collectors from the bus terminal in FUTA North gate, Cathedral, Ilesa garage, Benin garage, and Old garage were quantitatively analyzed. The I anamnesis and LP questionnaires were employed to establish the scores for nutrition, preventive behaviour, stress control, and social relationship.

There has been a change in traffic, which has resulted in poor comfort and agility in public transportation, as well as more irate individuals (drivers, fare collectors, and passengers) and increased employee responsibility (Faria, Amorim and Vancea, 2007). These realities may help to alter the lifestyle of these workers who spend long periods stuck in traffic (Faria, Amorim and Vancea, 2007).

Quantitative data collection emanates from 1st October to 31st October 2022. All active employees were invited to participate in this study through informative posters. The confidence level adopted for this study was 95% (p≤0.05), and chi-square was employed for data analysis. The chief researcher supplied the research tools after the invitation. At the outset of each work shift, employees were given a questionnaire, an anamnesis sheet, and a consent form to complete. Before data collection, no pilot research was conducted. The devices were sent to a total of 66 personnel, including 33 bus drivers and 33 ticket collectors.

The following were the study’s inclusion criteria:

a) being involved in the task;

b) correctly completing the questionnaire; and

c) returning the questionnaire within 7 hours of receiving it.

A total of 28 bus drivers (65.1%) and 15 fare collectors (34.9%) returned a valid questionnaire for data analysis and reporting. For data gathering, two instruments were used. The initial instrument was an anamnesis sheet created by the author. The subjects supplied some basic data for sample characterisation during anamnesis: name; business identification number; date of birth; age; sex; occupation (driver or collector); working hours (3 hours, 6 hours, or more than 6 hours); physical activity practice and the number of hours per week of physical activity; time on the job. Information on previous work experience and first employment were enquired.

The ILP [1] is a fifteen-question questionnaire that assesses five key areas of lifestyle: diet, physical activity, preventative behaviour, social relationships, and stress management. Each component consists of three questions, to which the participant must assign a number ranging from

(0) not part of your lifestyle,

(1) occasionally matching your behavior,

(2) almost always matching your behavior, and

(3) the assertion is always true in your day-to-day activities as part of your lifestyle.

The bus drivers’ and fare collectors’ lives were evaluated using the average answers to each question. Scores on the scale of 0 to 3 indicated how badly the habit affected one’s quality of life and how hazardous it was to their health. Positive behavior was defined as behavior between 2 and 3, whereas normal behavior was defined as behavior between 1 and 1.99 [1]. The values for each component were then added together to create a lifestyle profile that could be analyzed. The scale went from 0 to 9, with 0 - 3.99 denoting a terrible lifestyle, 4 - 6.99 denoting a typical lifestyle, and 7 - 9 denoting a positive lifestyle [22]. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normal distribution of the data, which were provided as means and standard deviations (SD).

The independent t-test was used to compare the results between drivers and fare collectors, and the chi-squared test was employed to check for significant connections between the responses and the work completed. The alpha of 0.05 was used as the significance criterion for all statistical studies. IBM SPSS, version 21, was used to conduct all statistical analyses (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Participants were 66 public transport employees (33 bus drivers and 33 fare collectors) from the bus terminal in FUTA North gate, Cathedral, Ilesa garage, Benin garage, and Old garage in Akure, Ondo state, Nigeria. A total of 28 bus drivers (65.1%) and 15 fare collectors (34.9%) returned a valid questionnaire for data analysis and reporting. The majority of the bus drivers who took part in the study were men (28; 100%), and their average age was 41.46 (±7.46). The fare collectors who took part in the study had a preponderance of men (15; 100%), and their average age was 32.41 (±7.77) years. Between the study’s participant worker groups, there was a connection in age (p < 0.001). Fare collectors were younger than bus drivers in age (mean difference of 9.05 years).

The majority of employees (bus drivers: 60.71%; fare collectors: 66.67%), including both bus drivers and fare collectors (No: 57.14%; Yes: 42.86%), did not engage in regular physical exercise. Bus drivers engaged in an average of 6.78 (6.4) hours of physical activity per week, whereas fare collectors engaged in an average of 5.33 (4.2) hours per week, with no significant differences between the two groups. Soccer, cycling, strolling, jogging, different combat sports, swimming, and strength training were among the physical activities that the workers engaged in.

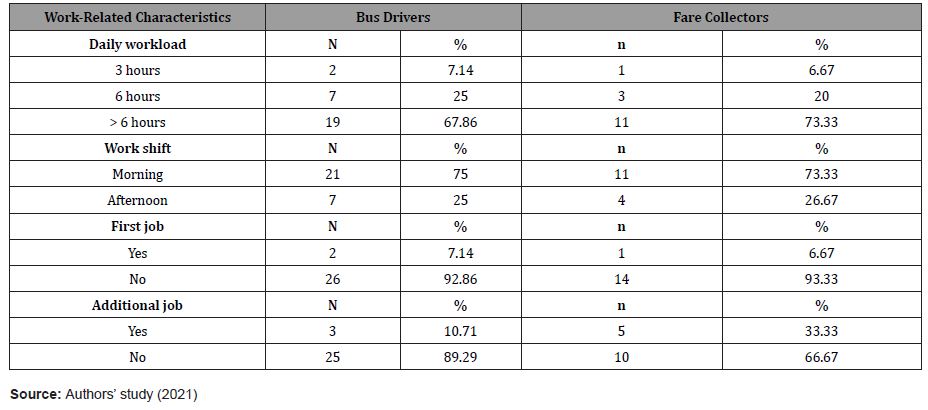

Table 1 presents the per cent values and/or the mean and standard deviation for the work characteristics. Majority of the bus drivers (67.86%) and fare collectors (73.33%) work for more than 6 hours daily. Most bus drivers (75%) and fare collectors (73.33%) worked the morning shift, were not on their first jobs (bus drivers = 92.86%; fare collectors = 93.33%) and did not have an additional job (bus drivers = 89.29%; fare collectors = 66.67%).

Table 1:Work-related characteristics of collective transport workers.

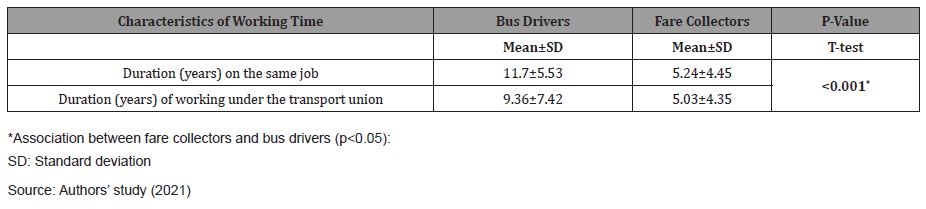

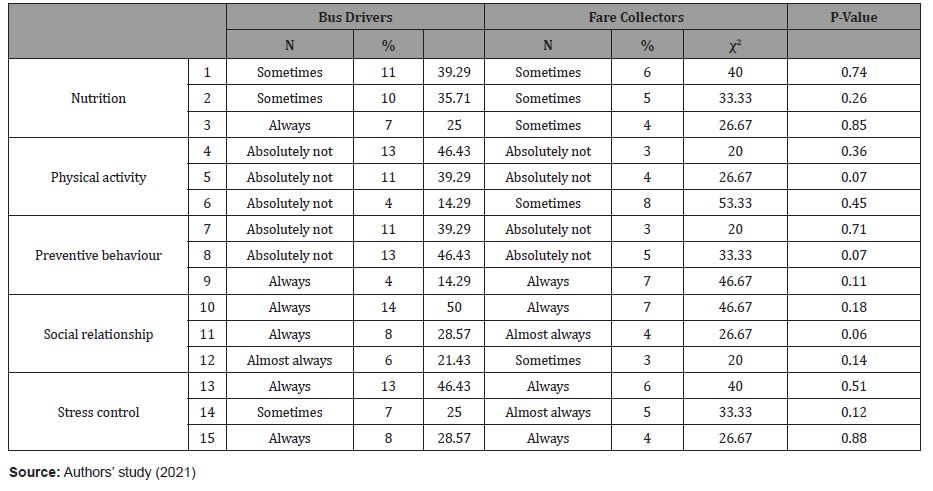

Time spent working and time spent with the company were related (p< 0.001). According to Table 2, bus drivers had been employed for a longer period of time than fare collectors (11.7±5.53 years vs 5.24±4.45 years), and they had also been affiliated with the transport union for a longer period of time (9.36±7.42 years versus 5.03±4.35 years). For each ILP question, the most popular response and its percentage value are displayed in Table 3. There was no relationship between the work completed and the answers to the ILP questionnaire.

Table 2:Working time characteristics of public transport workers.

Table 3:Association of the answer to each question of the ILP.

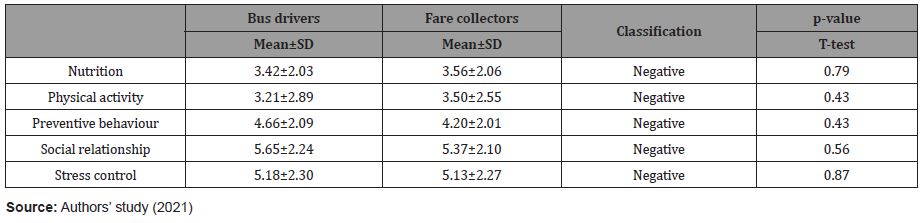

There were no associations between fare collectors and bus drivers, and the workers displayed negative behavior for the components nutrition (3.42 and 3.56; p=0.79) and physical activity (3.21 and 3.50; p=0.43) and regular behavior for the components preventive behavior (4.66 and 4.10; p=0.08), social relationships (5.65 and 5.37; p=0.56), and stress control (5.18 and 5.13; p=0.87) (Table 4).

Table 4:Mean score assigned by bus drivers and fare collectors.

Discussion

Nearly all of the workers on the jobs examined in this study were men. This result is in line with earlier studies on these professions [4, 7,11,12], and it seems to be related to the inherent danger of the work, as shown by the high rate of robberies and traffic accidents (Assunço and Medeiros, 2015). Due to the hierarchy of the profession and the need that applicants be 18 years of age or older to get a bus driving license Class D in Nigeria, the average age of bus drivers was also higher than that of fare collectors.

In this study, the percentages of occurrence for the five lifestyle factors did not change between the two jobs, and the food and physical activity parameters in both groups showed the most concern. When asked if they consume five servings of fruits or vegetables every day, many professionals periodically said “rarely,” indicating that their nutritional profile is inadequate and that they should change the way they eat. According to previous study, this behaviour may be explained by the little amount of time they have to eat and the difficulty in finding wholesome food at the bus line’s last stop [13] (Brito and Martins, 2012).

Additionally, more than half of the individuals did not engage in the weekly requirement of 150 minutes of physical activity for health promotion (Moura, Neto and Silva, 2012). Other research [4, 5,6,10,21] have shown sizeable percentages of workers who do not exercise, with mean values ranging from 25 to 66 percent. Regardless of their line of work, the people exhibited higher rates of inactivity than the male population (between 35 and 40 percent) [22].

Particularly fare collectors and bus drivers, their jobs need them to stand up often and sit for extended amounts of time [613]. According to Souza, Assunço, and Pimenta [4], [23], the main factor that promotes low levels of physical activity may be a lack of interest in or information about the benefits and motivation. Prior studies found that 29.1% of bus drivers did not engage in the minimum recommended level of physical activity before beginning their jobs, and this number increased to 56.4% once they were promoted to bus drivers [13].

Exposure to these conditions, in combination with the psychological strain of the job and poor eating habits, tends to increase the risk of depression or anxiety disorders, as well as overweight and obesity, which can lead to the development of cardiometabolic disorders like cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes [4,21, 23,24]. The PNPS [18] contains measures aimed at healthy nutrition, regular physical exercise, smoking prevention and control, and lowering alcohol and other drug usage in order to lower these risks. ILP domains provide as a good foundation for these efforts [18]. Professionals can also receive health benefits through occupational health promotion programs [25].

Government spending on workers’ health can increase with the introduction of health promotion policies and educational initiatives that benefit employees, employers, and the general public [24,25,26]. Some tactics, such as providing secure and convenient bike parking, guaranteeing appropriate and acceptable restroom facilities, allowing enough time to eat healthily, and developing a lifestyle awareness project, could encourage employees to walk and cycle to work and establish healthy eating habits [8,12]. In line with the principles and ideals outlined in the Health Promotion Policy for Workers, Managers, and Citizens [18], these new choices are being implemented to support specialized education, vocational training, and health promotion practices.

According to the research on the preventive behavior parameter, the workers who were questioned showed low compliance with blood pressure and cholesterol levels. These results are in line with recent study, which revealed that 31% of Brazilian men do not regularly check their health or seek assistance for illness prevention [26]. Lack of attention to physical and mental health is made worse by the stress that come with working in one of the unhealthiest professions and by ineffective coping mechanisms.

However, most drivers and fare collectors said that they use seat belts, adhere to traffic laws, and refrain from drinking before or while working when it comes to safety. These are important factors to take into account because accidents and incidents involving transit workers are categorized as public health problems [26]. A small percentage of workers in public transportation, ranging from 13 to 14 percent in various regions of Brazil, have been found to use alcohol [4,5]. Employees who reported less involvement in social activities had higher rates of alcohol addiction and dependency, according to a previous study [26]. This data supports our findings since it demonstrates that drinking, making friends, and general relationship contentment are all positive outcomes. The majority of workers claimed to have a healthy balance between work and leisure, which reduces stress.

In this study, prolonged periods of sitting, high percentages of inactivity, and poor nutritional quality were all noted. Data from earlier studies with this population in various Nigerian cities support similar findings. Few research have examined the lives of fare collectors and bus drivers who utilize the ILP, which limits the ability to compare our findings with their findings. Data from other studies that didn’t use a validated instrument may be compared with the data on physical inactivity, poor nutrition, a lack of healthcare, great social interactions, and stress management [4,8].

New studies on a variety of aspects of quality of life should be conducted over time. The effectiveness of physical and psychological intervention programs implemented by public sector organizations, such as active commuting, regular physical activity, improved working conditions (such as the adequacy of work breaks), and improved traffic and safety conditions, also needs to be studied [4,6,22,8]. The fact that everyone who was questioned worked for the same organization is one of the study’s shortcomings (Road Transport Workers). Additionally, socioeconomic status information was not included in the study; however, since the kind of job was limited to shared transportation, this impact was probably diminished [28].

Conclusion

This study compared bus drivers and fare collectors, and it found that there were disparities in age, length of employment, and organizational tenure, but not in lifestyle. Public transportation employees lead unhealthy lifestyles in terms of diet (fewer fruits and vegetables consumed, more fat consumed) and physical activity (inactive displacement and failure to meet minimum health recommendations). It is therefore recommended that fare collectors and bus drivers should eat enough fruits and vegetables, and reduce fat intake. The bus terminal managers should invite nutritionists and health managers to their terminal for health monitoring and sensitizations periodically.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of interest.

References

- Nahas MV, Barros MVG, Francalacci VO (2019) Pentagram of Well-Being: conceptual basis for evaluating the lifestyle of individuals or groups. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde 5(2): 48- 59.

- McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, et al. (2016) Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 17(3): 567-580.

- Bae SA, Fang MZ, Rustgi V, Zarbl H, Androulakis IP (2019) At the interface of lifestyle, behaviour, and circadian rhythms: metabolic implications. Front Nutr 6(132): 1-17.

- Souza LPS, Assunção AA, Pimenta AM (2019) Factors associated with obesity in road users in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol 22: 1-15.

- Assunção AA, Medeiros AM (2015) Violence against metropolitan fare collectors and bus drivers in Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública 49(11): 1-10.

- Moura AB, Neto M, Silva MC (2012) Diagnosis of working conditions, health and lifestyle indicators of public transport workers in the city of Pelotas RS. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde 5(17): 347-358.

- Battiston M Cruz, RM Hoffmann, MH (2006) Condições de trabalho e saúde de motoristas de transporte coletivo urbano Estud Psicol 11(3): 333-343.

- Chung YS, Wong JT (2011) Developing effective professional bus driver health programs: An investigation of self-rated health. Accid Anal Prev 43(6): 2093-2103.

- Winkleby MA, Ragland DR, Fisher JM, Syme SL (1988) Excess risk of sickness and disease in bus drivers: a review and synthesis of epidemiological studies. Int J Epidemiol 17(2): 255-262.

- Souza MGC, Silva CL, Pirschner F, Contarato GL, Braga LW, et al. (2009) Correlation of some lifestyle habits and working hours with blood pressure measured in urban public transport drivers. Rev Bras Med Work 5(6): 28-38.

- Simões MR, Assunção AA, Medeiros AM (2018) Musculoskeletal pain in bus drivers and conductors in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Ciênc Saúde Colet 23(5): 1363-1374

- Ghasemi S, Pirzadeh A (2019) Effectiveness of educational physical activity intervention for prevention of musculoskeletal disorders in bus drivers. Int J Prev Med 10(132): 1-15.

- Faria BK, Amorim G, Vancea DMM (2007) Food and anthropometric profile of bus drivers from the public transport company Jotur/Palhoça-SC. Rev Bras Obesity Nourish Weight Loss (1): 11-20.

- Tarane K, Fredrick J, Gaur GS, Aruna R, Dhanalakshmi Y (2019) Heart rate variability among long-distance bus drivers after a night shift. Int J Physiol. 7(2):50-4.

- Wei C, Gerberich SG, Ryan AD, Alexander BH, Church TR, Manser M (2017) Risk factors for unintentional occupational injury among urban transit bus drivers: a cohort longitudinal study. Ann Epidemiol 27(12): 763-770.

- Pradhan CK, Chakraborty I, Thakur S, Mukherjee S (2018) Physiological and metabolic status of bus drivers. In: Ray G, Iqbal R, Ganguli A, Khanzode V (2018) Ergonomics in Caring for People. [Switzerland]: Springer Singapore, pp. 161-167

- Almeida NDV (2010) Considerações acerca da incidência do estresse em motoristas profissionais. Rev Psicol 1(1): 75-84.

- Ministério BR (2014) Secretary of Health Surveillance, Secretary of Health Care. National Health Promotion Policy: review of the Ministry of Health Ordinance.

- Carvalho AFS, Dias EC (2012) Health promotion in the workplace: systematic literature review. Rev Bras Promoç Saúde 25(1): 116-126.

- Silva EM, Sousa AC, Kumpel C, Souza JS, Porto EF (2018) Lifestyle of individuals using the unified health system. LifeStyle J 5(2): 61-75.

- Pinto ECT, Bueno MB (2019) Nutritional assessment and eating habits of public transport drivers in the city of Jundiaí-SP. Rev Assoc Bras Nutr 10(1): 53-58.

- Silva ICM, Mielke GI, Bertoldi AD, Arrais P, Luiza VL, et al. (2018) Overall and leisure-time physical activity among Brazilian adults: a national survey based on the global physical activity questionnaire. J. of Phys Act Health 15(3): 212-218.

- French SA, Harnack L, Toomey TL, Hannan PJ (2007) Association between body weight, physical activity and food choices among metropolitan transit workers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 4(52): 1-12.

- Morais RA, Souza DT, Ferron AJT, Souza CT, Francisqueti FV (2018) Characterization of the dietary pattern and nutritional status of public transport drivers in the city of Bauru-SP. Rev Bras Obesidade Nutr Rev Bras Promoç Saúde 32: 9733, 12(71): 293-300.

- Brito ECO, Martins CO (2012) Perception of participants in the Labor Gymnastics program on flexibility and factors related to a healthy lifestyle. Rev Bras Promoç Saúde 25(4): 445-454.

- Cunha NO, Giatti L, Assunção GA (2016) Factors associated with alcohol abuse and dependence among public transport workers in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte. Int Arch Occup Environment Health 89(6): 881-890.

- Ministério BR (2016) More than 70% of workers do not exercise regularly Brasília: Ministério da Saú

- Guterres A, Duarte D, Siqueira FV, Silva MC (2011) Prevalence and factors associated with back pain in drivers and collectors in the city of Pelotas-RS. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde 3(16): 240-245.

-

Adeniran Adetayo Olaniyi*, Ilugbami Joseph Olanrewaju, Fakunle Olutayo Sunday and Tayo Ladega Oluwadamisi. Healthy Lifestyle of Fare Collectors and Bus Drivers in Akure, Nigeria. On J of Arts & Soc Sci. 1(1): 2023. IOJASS.MS.ID.000503.

-

Hyperlipidemia, Hyperleptinemia, Hepatic steatosis, Accuracy, Self-control,

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.