Research Article

Research Article

Tunisian English Language Teachers’ Attitudes and Self-Reported Efficacy Beliefs: Washback of the High- Stakes English Baccalaureate Exam

Hanen Dammak1*, Ali Khatibi2 and SM Ferdous Azam3

1Institute of Higher Commercial Studies of Carthage, University of Carthage, Tunisia

2Management and Science University, University Drive, Off Persiaran Olahraga, Section 13, 40100, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

3Management and Science University, University Drive, Off Persiaran Olahraga, Section 13, 40100, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Hanen Dammak, Institute of Higher Commercial Studies of Carthage, University of Carthage, Tunisia.

Received Date:August 11, 2023; Published Date: August 28, 2023

Abstract

Researchers have shifted their attention from the quality of the design of the test to beliefs because of the power of beliefs in shaping what is taught and how it is taught. The effect of teacher-related factors has triggered wide research, especially in high-stakes examinations. This paper examines the attitudes of ELTs towards the high-stakes English Baccalaureate exam and their self-reported efficacy beliefs and their teaching practices. For so doing, a questionnaire was administered to English language teachers teaching the 4th form of secondary school (N= 364 ELTs randomly selected). In the hope of reaching a deeper understanding of the respondents’ personal accounts of their perceptions, a follow-up study (resulting from classroom observations and semi-structured interviews, N=4 ELTs) enabled a close reading of the aspects relevant to the question. Using SPSS version 23 for data analysis, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient and simple and multiple linear regression models were computed. As a result, statistically significant links were found between teachers’ attitudes and their self-reported efficacy beliefs on the one hand, and their teaching practices on the other hand. The findings are liable to guide different stakeholders and policymakers to establish appropriate policies for effective teaching practices to be deployed.

Keywords:Washback; Attitude; High-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam; Self-reported efficacy beliefs

Introduction

Washback or backwash, the impact of examinations on the different facets of a classroom—including participants, process, and product—has been the subject of extensive research in different educational settings [1]. High-stakes examinations have typically been used as catalysts for educational reform to assist in the implementation of innovative practices, to establish accountability purposes, and to influence teachers to align to the requirements of the reform, and consequently to adapt and develop innovative teaching practices. “It is testing that becomes the driving force behind what is learned and how it is learned” [1].

Language testing can be approached from two different perspectives: conventional testing and use-oriented testing [2,3]. Traditionally, test designers and users have placed great value on the quality of the design of the test in order to ensure its usefulness and improve teaching strategies [4-7]. However, researchers have argued that adjusting exam designs will not necessarily result in enhancing teaching and ensuring better learning. There will still be a washback effect regardless of the quality of the design of the test. Researchers become more interested in how tests are used in educational, social, and political contexts and in explaining the factors that hinder the teaching of English and influence the teaching-learning process.

There appears to be an agreement among researchers that washback exists, but they disagree on its nature, scope, mechanism, or incentives. They have acknowledged that washback is usually triggered by the behavior of several independent and mediating factors other than the test itself. Other variables rather than the exam itself, such as students, teachers, parents, and the school environment undoubtedly contribute to the washback effect and impede the intended and desired changes [8,9]. Teachers as key agents play a key role in educational reform and contribute significantly to the generation of washback. Their base knowledge, understanding of the principles, their knowledge of the principles underlying the test, and levels of resourcing within the education system are likely to impact the teaching process. Although it is generally acknowledged that the teacher-related factors play a key role in the washback process, little is known about the phenomena. Hence, as high-stakes tests continue to be important and influence the fate of thousands of students, it is of paramount significance to examine teachers’ attitudes and beliefs since these are factors that shape and determine their teaching.

Literature Review

This section reviews the literature related to research that informs the present study.

Scholars have examined teacher cognition and the link between their cognition and their teaching practices [10-14]. Because of the ever-growing body of research on teacher cognition, several definitions of beliefs have been elaborated. However, the current study adopts the general agreement about the construct beliefs. Hence, beliefs are the perceptions, views, ideas, thoughts, knowledge, and understandings that teachers hold [15-17]. Teachers’ beliefs are related to their pedagogical viewpoints, which are connected to thoughts about teaching and learning languages (Borg 2001). Their beliefs predict and explain their teaching strategies, resources, activities, classroom materials and all other aspects of their classroom in general.

Researchers claim that teacher-related factors including personal, social, psychological, and environmental realities of the school and the classroom “are determinant of actions” and they influence teachers’ instructional practices [15,16]. Within the corpus of language teaching-learning literature, there are several studies that claim the existence of significant relationships between beliefs and practices, while some others argue that there is no connection between beliefs and actions.

The first type of belief that gained some attention in the literature is teachers’ attitudes towards the high-stakes examinations. Previous studies on the perceived impact of high-stakes tests have yielded contradictory results about teachers’ attitudes toward exams in terms of feelings, beliefs, and perceptions. Teachers show a range of mixed and contradictory attitudes (e.g., Chou, 2017; Tanguay, 2020), ranging from negative [Barnes, 2017; 8, 16, 18-20) to positive (e.g., Cholis & Rizqi, 2018; 21).

Gunn et al. [22] investigated the washback effect of high-stakes exams on teachers’ perceptions and emotions in a Midwestern state in the United States using a mixed-methods approach. Teachers were under stress and had a negative attitude toward the test, according to their findings. Likewise, in Libya, Ahmed [8] conducted a preliminary investigation into the washback of the Secondary Education Certificate Examination (SECE). The findings revealed that the participants believed their goal was to achieve high exam scores and teach English as a subject rather than to boost students’ performance. Similarly, Nguyen and Gu [19] examined the perceived impact of the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) on the teaching of English. The results of their study showed that there was no significant variation in how individual teachers responded to the test. In Riyadh Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a research study was conducted by Binnahedh to investigate both students’ and teachers’ attitudes toward a new type of testing called e-tests, as well as students’ washback effects of e-tests. Using two different versions of questionnaires for teachers and students, the researcher also looked into what may affect students, teachers, the educational environment, and the curriculum. The findings of the research show that e-tests had an impact on both teachers and students, as well as their perceptions and the materials used. Furthermore, the widespread use of multiple-choice questions (MCQs) has discouraged students from being creative and innovative, along with teachers’ inclination to teach and cover only what is included or related to the exam (2022). Binnahedh found out that the exam generally made teachers feel overwhelmed and worried and worked hard to align to the requirements of the test.

Contrary to the aforementioned studies, Hartaty conducted a case study in a public junior high school in Indonesia to investigate the implementation of a new policy of the National Examination (NE). The findings point toward the fact that the 2015 new policy might have shifted the NE from a high-stakes test to a lower-stakes test and the new policy generated a positive washback on English language teaching. Likewise, using a questionnaire, Cholis and Rizqi (2018) examined how a high-stakes test Seleksi Bersama Masuk Perguruan Tinggi Negeri, the Entrance Exam of Universities (EEU) in Indonesia (SBMPTN) may influence teachers’ attitudes and their instructional strategies. The results of their study show that SBMPTN had a positive washback effect on teachers’ attitudes and their teaching practices. Equally, Estaji & Alikhani [18] examined what teachers and students believed about the impact of the First Cambridge in English (FCE) exam on the class materials and preparation books. The findings indicate that both the teachers and students had positive opinions on the washback of the FCE exam on their course materials and teaching. Overall, most of the teachers (90%) stated that the FCE exam had an impact on their teaching and that they favored preparing their lessons in alignment with the FCE assessment methods. Their teaching integrates both general English and test-taking strategies in order to prepare their students for the test.

The second type of belief refers to teachers’ self-reported efficacy beliefs that may affect their instructional behaviour. Selfefficacy is one of the self-belief systems which plays a major role in the manner of dealing with an issue, achieving a goal, or dealing with a specific matter. Studies on self-efficacy yielded inconsistent results. Some research studies [e.g., Ghaith & Yaghi, 1997; 23-25] reveal the absence of a significant relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and their teaching practices, asserting that “there is no evidence that teachers’ sense of self-efficacy increases or decreases with experience” [23]; other research [26-30] show a significant correlation between teachers’ self-efficacy and their teaching behavior.

Ortaçtepe & Akyel [24] sought first to investigate the connection between EFLs’ self-efficacy and their self-reported teaching practices, and then to evaluate the effects of an in-service teacher education program on their self-efficacy and actual teaching practices, using a self-reported questionnaire administered to 50 EFLs and observing 20 teachers. The results revealed a statistically insignificant relationship between teachers’ efficacy and their teaching practices. They also showed that in-service teacher education programs increased instructors’ self-efficacy but had no impact on their instructional practices. Similarly, using two criteria: gender difference and teaching experience, Mashhadlou and Izadpanah [25] studied EFL teachers’ performance. The findings of their study indicate that there is not any significant difference between less experienced teachers (less than 5 years) and experienced teachers (more than 5 years).

Unlike the above-mentioned researchers, Jäger et al. [31] conducted a longitudinal quasi-experimental study in two German states to examine the impact of low-stakes examination. The findings of their study revealed that the teachers with high selfefficacy who believe that they can teach very demanding students were likely to narrow the content and respond to the exam more than those who did not hold self-efficacy beliefs. Recently, Shahzad and Naureen [32] looked into the effect of teacher self-efficacy on teaching practices and subsequently on student achievement. Teachers’ self-efficacy influences their teaching practices. Teachers with a high level of self-efficacy are more confident and can control their emotions and their teaching behavior. Equally, Gebril and Eid [9] conducted a quantitative-qualitative study to examine English language teachers’ perceptions and practices about test preparation. They state that self-efficacy is a key factor in determining the teachers’ positive beliefs about test preparation. Hence, those who have high self-esteem are more exam oriented. Likewise, Al Amin and Greenwood [26] conducted a quantitative study investigating teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about what makes an effective teacher, their understanding of the curriculum and their instructional behavior. They identified the various barriers to curriculum implementation, such as teacher preparation and experience, as well as the prevailing misconceptions regarding the Communicative Language Teaching approach. They also highlighted the differences between the respondents’ stated understanding of the curriculum and their teaching practices. This is further confirmed by Koizumi [28] who recently investigated the variables that hinder teaching and the use of summative and formative assessment. It was found that (a) teacher factors like self-efficacy and training, (b) the nature of assessment, and (c) contextual factors that make classroom assessment challenging are the three factors that influence and determine the nature of classroom teaching and assessment. He concluded that the more experienced teachers are more self-assured, exam-focused, and negatively influenced. They align their teaching with the requirements of the test and disregard the principles and objectives of the curriculum, feeling better qualified to determine what is useful and practical in their teaching and educational settings.

Teaching practices

Teaching practices refer to what and how EL teachers teach using the strategies and techniques to achieve the objectives of a particular lesson. Generally, teaching approaches are classified into two broad approaches using a variety of criteria. These features might include classrooms that are more learner- or teacher-centered [33]. The traditional classroom is described as a teacher-dominated environment where teachers transmit knowledge. Learners in the learner-centered classroom are active and engaged in problem-solving activities with the teacher serving as a facilitator and guide. Hence, when planning teachers consider the teaching materials, the activities, the skills to be taught, and the interaction pattern. When teaching, they create a friendly and encouraging atmosphere, present material in manageable units with opportunities for practice, encourage communication, boost creativity and critical thinking. The present paper uses the terms teaching practices, instructional practices, instructional behavior, strategies, and actions interchangeably to describe how and what teachers teach in real classrooms.

Although the washback effect has received substantial attention in many educational contexts, researchers still encourage conducting further research on the role of teacher-related factors in the educational contexts where exams have been operating for a long time (ref). Understanding the beliefs of teachers who are at the front line and the correlation between their beliefs and their teaching practices would help determine strategies for improving English instructions, fostering the development of students’ skills, and improving their English proficiency. Hence, exploring the impact of teacher-related factors on their teaching practices is still an area that requires further investigation, as in the Tunisian context where the English Baccalaureate Exam has not been taken into consideration. The present research makes a step toward an under-researched area in the local Tunisian educational context by investigating the role of teacher-related factors within the context of the English Baccalaureate Exam and assessing the correlations between teachers’ attitudes, and self-reported efficacy beliefs and their teaching practices.

Assessment Context in Tunisia

The field of language testing in Tunisia is still in its infancy. There has been very little research in applied linguistics; and language teaching and testing have only recently shown interest in classroom assessment. Language assessment is primarily conceived as summative (Hidri, 2015, p.34). The Tunisian education system is characterized as exam-oriented, in which assessment is “a way to evaluate students on whether they pass or fail rather than a way to develop their critical thinking skills to overcome the various language problem-solving tasks that tests may contain” (Hidri, 2015, p.34). This research was conducted in secondary schools in Tunisia within the context of the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam (EBE). This section gives worldwide readers some background information about this educational context, the teaching and testing of English.

Influenced by the French education system, the Ministry of Education (MoE) in Tunisia continues to use the Baccalaureate Exam (BE) as a secondary school leaving and an admission exam to higher education which has been around for more than a century [34,35]. All students must take the challenging BE at the end of the fourth form of secondary education.

High-stakes exams in Tunisia as in other Arab country, are used to assess students and they determine the future of thousands of students each school year. There are three standardized national exams: Primary Education Certificate (PEC), Basic Education Certificate (BEC), and Baccalaureate Certificate (BC). Students in primary and lower secondary levels who want to attend pioneer middle and secondary schools must take and pass the PEC and BEC exams. However, all students must sit for the BE, a gatekeeper exam, at the end of the 4th form of secondary education. The BE is managed and administered by the education board, the exams council, and regional examining boards in June at the end of the academic year. The MoE external agencies assess, administer, and grade the exam scripts anonymously to ensure equal chances for all candidates and to ensure fairness.

Owing to the importance of English in the global market, the Tunisian Ministry of Education (MoE) committed itself to adhere to the international norms and subsequently to reform the teaching of English. When compared to other countries in the MENA region, Tunisia has significantly invested in the education system since its Independence in 1956 to promote educational innovation and meet international standards. Political, social, and economic changes all contribute to ongoing changes in the status of the English language. At all educational levels, the teaching of English has become increasingly important for Tunisians.

Given its importance in education, research and professional and vocational skills market, English, a core subject, is taught as a foreign language in elementary, middle, secondary, and higher education. However, despite the continuous efforts of the MoE to improve students’ language learning, particularly English, and to give teachers, who are on the front lines and in charge of carrying out the curriculum, the knowledge and skills that they need to teach more efficiently, students’ performance remains low [36,37].

Several policies reforming Tunisia’s linguistic status have been issued since 1994. The teaching of English was particularly promoted [38]. Consequently, there was a reform in language teaching and testing; a shift in the pedagogical focus from the conventional approach to the communicative approach of language teaching to enhance language proficiency. Additionally, it sought to involve students in the learning process, foster critical thinking and creativity, and solve real-world problems. As a result, rather than being teacher-centered, the classroom becomes learner-dominated. Public and private schools alike in Tunisia use the same texts and curriculum, which highlights the core objectives and principles of teaching English (Department of Pedagogy and Norms of Basic and Secondary Education). Like many other countries, the education system in Tunisia has defined the principles and standards of teaching English. It has adopted a principled and reflective Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach using a Task- Based Language Teaching (TBLT) methodology: pre-task, whiletask, and post-task to vary and improve the teaching techniques and strategies and serve different learning styles. The main aim was to develop the four language skills (reading, listening, speaking, and writing) in an integrated way, including various sub-skills and strategies. The role of the teacher is mainly to facilitate and guide learners through the process of learning by creating a friendly and positive environment that encourages communication, presenting authentic materials that enhance real-life communication, providing opportunities for learners to practice, and supporting creativity and critical thinking. Communicative language teaching encourages the learner to express themselves and connect with other students, enabling access to global culture by exposing them to appropriate English-speaking environments. Meaningful linguistic input primarily aids in the learner’s development of their spoken and written language skills.

The exam was originally intended to measure students’ English proficiency at the end of their 4th form of secondary education. Getting high scores in national examinations opens wide doors to students by entitling them to get their first choice of the college, university, and discipline to follow. The fact that scores determine admission decisions causes teachers to feel frustrated and anxious about ensuring high scores. Because of its detrimental effect, all parties involved—directly or indirectly— are concerned and seek to ensure that students receive high marks. This race for high scores in the high-stakes Baccalaureate exam is akin to paranoia, and it is on the verge of becoming a national social phobia in scope and breadth [39]. In this distressing exam context, the improvement of exam scores is placed ahead of the teaching objectives. Working from this perspective and since “beliefs are considered to be one of, if not the most influential factor on teachers’ instructional practices,” teachers’ perceptions of the exam, their self-efficacy beliefs and how they behave accordingly may lead to different practices with varying degrees [15]. In other words, in order to ensure that their students receive high grades and to open up a world of possibilities for them, allowing them to choose their college, university and discipline of study, teachers tailor their teaching practices and do not have much of a choice but “to do things they would not otherwise do” to ensure that their students receive high grades [40].

A main session and a re-sit session are held in the month of June. In order to offer students time to unwind and better prepare, the main session lasts six days. All students who received at least an average score of 7 out of 20 are eligible for the re-sit session that lasts 4 days. It often begins two or three days after the dissemination of the results of the main session. Usually, students sit for a physical education test in addition to written and practical tests. Generally, they sit for at least six core subjects and two electives with varying durations and coefficients [41]. The current English Baccalaureate Exam has been in operation for more than 14 years.

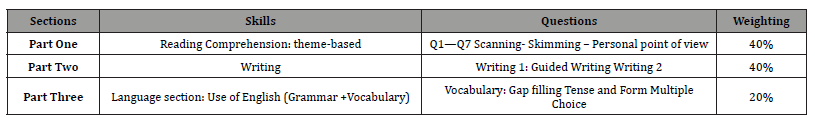

The English Baccalaureate Exam is composed of three parts: reading comprehension (40%), writing (40%), and language (20%). There are seven questions in the reading comprehension section. Writing makes up Part 2 of the test and is broken down into two questions that assess the students’ writing skills. Part 3 is the language part, which has three tasks. The different components of the exam are described in Table 1. Regardless of the intended goal behind adopting the English Baccalaureate Exam and applying the communicative method, the test fails to assess two essential skills: speaking and listening for practicality reasons (Table 1).

Table 1:An Overview of the English Baccalaureate Exam.

Nonetheless, though the English Baccalaureate Exam has been generally used as an exit and entrance exam and a condition for job applications, neither the structure nor the content of the test have been validated. They seem to be developed in conformity with previous tests rather than according to theory informed test specifications [42]. Little is known about the impact of English Baccalaureate Exam on classroom teaching practices. There is a significant gap in the current literature and research on the washback effect of the English Baccalaureate Exam and the different factors that may contribute to and affect classroom instruction in the Tunisian context. Because of the power of the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam, it is urgent to examine what is happening within the classroom context that leads to the mismatch between high scores in the English Baccalaureate Exam and low English proficiency.

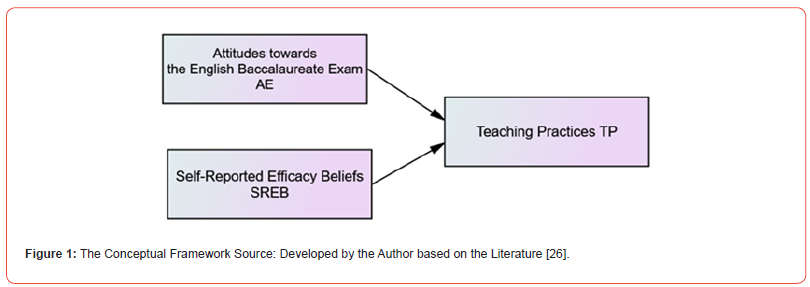

Given the dearth of research on the impact of the English Baccalaureate Exam in Tunisia and the many variables that can have an impact on the teachers’ teaching practices, the present research is limited to examining two factors mainly teachers’ perceived effects of the English Baccalaureate Exam and their self-efficacy beliefs. Another objective was to examine the relationships between teachers’ different beliefs --specifically, their attitudes towards the exam and their self-efficacy beliefs-- and their instructional practices. Consequently, two hypotheses were developed to help understand the overall goal which is to fill a substantial research gap and investigate the impact of (i) teachers’ attitudes toward the English Baccalaureate Exam (AE), and (ii) their self-reported efficacy beliefs (SREB) on their teaching practices (TPs). The knowledge gained from such a study would be useful in determining the relationship between teachers’ selfbelief system as well as their teaching practices. It would also be beneficial to a number of stakeholders, including teachers, students and policymakers. This study could add to the limited literature in language teaching and assessment so as to understand the nature of this problem and how it affects teaching practices.

Research Questions

The present study addressed the following research questions:

• Do ELTs’ attitudes towards the English Baccalaureate

Exam affect their instructional practices?

• Do ELTs’ self-reported efficacy beliefs affect their teaching

practices?

Methodology

To achieve the research objectives of the current study, two relationships were developed based on the suggested conceptual framework. Figure 1 illustrates an adapted conceptual framework that was developed in view of previous related studies (Figure 1).

Research Design

Motivated by the discrepancies of the different research finding and in order to investigate the impact of ELTs’ attitudes toward the English Baccalaureate Exam and their self-reported efficacy beliefs (SREB) on their teaching practices (TPs), the current study relied on a deductive quantitative approach using a selfreported questionnaire, non-participant classroom observations, and semi-structured interviews during two phases. During Phase 1, a questionnaire was administered to 4th form English language teachers to investigate the perceived effects of the highstakes English Baccalaureate Exam and identify the significant relationships between teacher-related variables and their teaching practices. In the second, qualitative phase, from February to May 2020, four teachers of 4th form classes were interviewed after they were observed to get a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. The original quantitative results of the survey were discussed, explained, and explored in greater depth.

Participants

In order to reduce the probability bias and to make a generalization, this study followed probability random sampling; any English teacher teaching the 4th form of secondary school would be eligible to participate in the study. Using Krejcie and Morgan’s table that ensures an appropriate choice of sample size [43], a sample of 327 ELTs from a total of 2078 ELTs is considered adequate. However, in order to obtain a confidence level of 95% that the real value is within 5% of the measured value, 335 is the adequate sample size required. Hence, 450 questionnaires were administered to 4th form ELTs throughout the country. A total of 364 teachers filled and returned the questionnaire from 26 regional educational commissions. The overall response rate was around 81%. After data cleaning, 8 invalid questionnaires from the 364 returned questionnaires were not considered in the analysis of 356 valid questionnaires.

Of the 356 participants, 72.2% were females and 27.8 % were males. The vast majority were in their late middle age. 78.4% of the teachers were 41 and above. For academic qualifications, the majority (78.4 %) of the respondents have a Bachelor’s degree in English, 21.3 % have a Master’s degree, and.3% have a Ph.D. 88.5% of the respondents have been teaching the 4th form of secondary education for more than ten years. While only 11.5% have been teaching for less than 6 years. In terms of professional development, 46.4% of the participants had attended more than 10 workshops within the past five years compared to 11.2% who did not attend any training.

Research Instruments Phase 1: Self-reported Questionnaire

As the English Baccalaureate Exam is very typical in Tunisia, a questionnaire was developed based on prior research studies in the field. Most of the questionnaire items were adopted and adapted from established questionnaires on perceived effects of the exam (Pedulla et al., 2003), self-efficacy beliefs [9,31], and the teaching practices statements [Lai & Waltman, 2008; 9]. The current survey consisted of only closed-ended questions to explore two major themes: ELTs’ beliefs and their practices. The first section collected the most important demographic data, such as age, gender, teaching experience, and educational background. The purpose of section two was to get ELTs’ thoughts on the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam and its impact. Sections three, four and five were designed to (i) fully understand the common practices used by ELTs in their classrooms and how much time they spent working on various skills on a typical day, (ii) identify the common practices used by ELTs in their classrooms to prepare their students for the Baccalaureate Exam, and (iii) truly comprehend the frequency and time frame in which ELTs prepare their students for the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam. Section six elicited the respondents’ self-efficacy beliefs

Phase 2: Classroom Observations and Semi-Structured Interviews

Classroom Observation: classroom observations were carried out to learn more about the participants’ actual teaching practices and to look for any relationships, consistency issues, and any discrepancies between their attitudes, self-reported beliefs, and their actual behaviors. Only four teachers who answered the questionnaire volunteered to accept the researcher to observe their classrooms from February to May 2021. Using a structured classroom observation checklist and a voice-recorder, each lesson was recorded, transcribed, and examined.

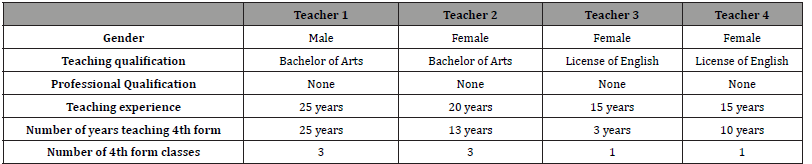

The description of the teachers who participated in the followup study, their gender, education and professional qualification, their teaching experience as well as the number of years teaching the 4th form of secondary education are displayed in table 2. For anonymity, participants are numbered as T1, T2, etc (Table 2).

Table 2:Demographic Details of the Observed Teachers.

All 4 teachers were EFL teachers working in the same school. Of the 4 participants, only one teacher was male. The ELTs had a wide range of teaching experience teaching the 4th form of secondary school ranging from 3 to 25 years.

Semi-Structured Interviews: The goal of the semi-structured interviews was to get a better understanding of ELTs’ accounts of their perceptions of the English Baccalaureate Exam. The 4 ELTs who agreed to allow the researcher to observe their classes were interviewed. All four interviews were recorded, transcribed, and sent to the interviewees to double-check their answers and give their approval.

Testing and Item Modification

As the questionnaire was adopted and adapted, it went through a cyclic thorough validation process. Five experts from the field of language teaching and testing were emailed and requested to judge the quality of the instruments, give their feedback in terms of face validity, content validity, criterion-based validity, and construct validity, to check whether the various data collection instruments, i.e., the questionnaire, the classroom observation and semistructured interviews measure the concept and not something else, and to add any additional comments that might improve the quality of the instruments [44]. Three ELTs of the same background of the target population were asked to read the questionnaire loudly, to give their feedback and to check the wording, ambiguity, and suitability of the questions. Due to a lack of clarity, some questions were revised, while others were removed as a result of the testing. Besides, some wording changes were made so that the target audience would not have trouble understanding specific constructs, and some important concepts were replaced with nontechnical terms.

Piloting

An iterative process of testing and retesting of the questionnaire was followed. Following the general rule, thirty ELTs with similar backgrounds in language teaching 4th form of secondary school assisted in testing the reliability of the questionnaire and improving the quality of the data collection instrument. The pilot study helped identify flaws and improve the quality of the data collection instruments. Before the final version was finalized, the data collection instruments were tested a second time after being modified as needed. Finally, the modified version of the questionnaire was re-administered to the same group of ELTs to ensure consistency, correctness, and efficiency.

Data Collection Procedures

With the Covid-19 outbreak and in response to the measures taken, it was not possible to contact the participants in person. Upon written approval from the MOE, English language teacher educators were contacted to assist in distributing the questionnaire to 4th form English language teachers. Having committed themselves to assist and to be neutral and not to exercise any type of pressure on the participants, the teacher educators were given an overview of the purpose of the study. In their meeting in October 2020, ELTs were requested to fill out the questionnaire and submit it. Among those who answered the questionnaire, some ELTs volunteered to participate in the follow-up study. Given the time and cost involved in observing and interviewing, the researcher chose participants in the closest governorate who (i) answered the self-reported questionnaire in Phase 1, (ii) expressed their willingness to participate in the follow-up study, (iii) had some individual variance, and (iv) represented heterogeneity such as gender, teaching experience, and the number of years teaching the 4th form of secondary education.

Data Analysis Quantitative Analysis

To get a full understanding of the multi-faceted phenomenon, SPSS 23 was used to analyze the quantitative data collected through the questionnaire. Negatively worded items were reverse coded before the analysis. Both descriptive and inferential analyses were used. As for the qualitative data gathered from both the classroom observations and the interviews and prior to any analysis, both the researcher and the intercoder agreed on a predefined set of codes or concept-driven coding to select what serves the present research. Despite the data being highly structured, intercoder consistency was used to provide confidence by representing a reliable description of the data and increasing the consistency and comparability of the coding process.

Prior to any statistical analysis, different tests for various assumptions were performed to ensure that the data were suitable for inferential statistical analysis. After checking the different assumptions and as the data deemed to meet the assumptions that the model must satisfy, meaningful conclusions about the population can be obtained from the sample. Hence, Pearson Product-Moment Correlation and simple linear regression and multiple linear regression were computed to check if one or more predictor variables, i.e, AE or SREB, could explain the dependent variable TPs.

Abbreviations were used to avoid being too wordy; AE and RSEB were used to refer to the teachers’ attitudes and self-reported efficacy beliefs, while TPs were used to refer to the teachers’ stated teaching practices.

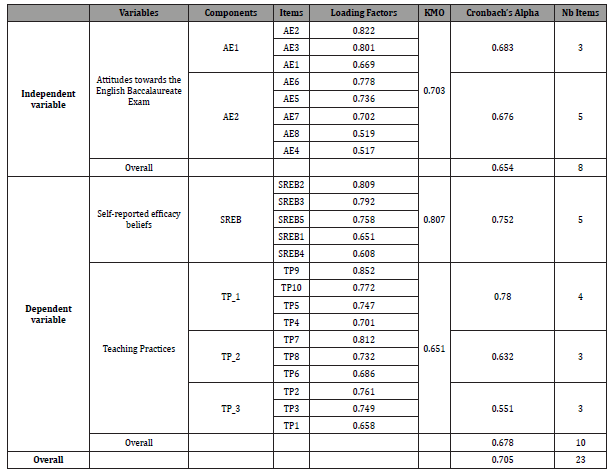

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to recognize the common factors that explain the structure of measured variables (Fabrigar &Wegener, 2012; Watkins, 2018) [45]. To extract factors, three main criteria were used: (i) a minimum of three items in one factor with an eigenvalue of 1 or greater; (ii) factor loadings of less than.4 were excluded and not counted in any factor; and (iii) items with double loadings were deleted. The criteria variables within a single component are highly connected, and there are no significant cross-loadings between factors, ensuring both convergent and discriminant validity in factor extraction. A principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted to recognize the common structure of the factors obtained from the different variables and to check whether they represented a single construct.

A PCA on the 9 survey questions AE1 through AE 9 generated two factors: factor one with an eigenvalue of 2.377, accounting for 29.718%, factor two with an eigenvalue of 1.787, accounting for 22.342% of the total variance. 8 survey questions clustered together around teachers’ attitudes. Item 9 was excluded from factor extraction due to the requirement of a minimum of three items. Two factors were extracted and retained for further analysis. The sampling adequacy KMO value is.703and its Cronbach’s alpha is .654.

Besides, the 10 items to measure the teachers’ teaching practices were subjected to a PCA to check if they represented a single construct. The analysis yielded three factors, factor one, with an eigenvalue of 2.784, accounted for 27.836% of the total variance; factor two, with an eigenvalue of 1.604, accounted for 16.038%, and factor three, with an eigenvalue of 1.445, accounted for 14.452%.

As for the SREB, the analysis yielded a single factor with an eigenvalue of 2.649, accounting for 52.988% of the total variance. Five survey questions clustered together around teachers’ selfefficacy beliefs. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs are reported in items SREB 1 through SREB 5. A summary of the factors obtained their loading factors, their sampling adequacy KMO value, and the Cronbach’s Alpha for each factor are given in (Table 3).

Table 3:Summary of AE, SREB and TPs Factor: Loading Factors, KMO and Internal Reliability.

To examine the relationship between the teachers’ attitudes and their teaching practices and to make generalizations about the larger population from the sample of participants, inferential statistics were used. Pearson Correlation coefficient, SLR and MLR were calculated to test the strength of the relationships between teachers’ attitudes and beliefs and their teaching practices.

Qualitative Analysis

The researcher and the inter-coder agreed on the codes after discussing the pre-established coding framework obtained from the literature. All of the Tran scripted interviews were initially entered into an Excel spreadsheet that included a section for individual reflections and comments. Following the deductive theme analysis and utilizing the already defined coding framework, the analysis was completed in stages by allocating different colors for each group and highlighting comments. By using the same codes for the entire data set, the data was first coded. Following data interpretation, numerous units of meaning were classified, categorized, and ordered in accordance with the research questions [46].

The researcher focused on specific behaviors and acts and sought regularities and irregularities in relation to the basic principles of the CLT approach and TBLT methodology. In other words, the purpose was to examine the extent to which the teaching practices were communicatively oriented, with a focus on the methodology, content, skills, activities, and pattern of interaction. To secure accurate data, the researcher and the intra-rater both examined the codes and the coding rubric and worked on samples. They regularly met following each observation to review and discuss the data collected to gauge their degree of agreement and “to ensure that the observational categories themselves are appropriate, exhaustive, discrete, unambiguous and effectively operationalize the purpose,” which was to better report ELTs’ teaching practices and to objectively report events and actions that occurred in the classrooms [47].

Results

The following sections report the findings from the different

data collection methods, i.e., questionnaire, classroom observations

and semi-structured interviews.

RQ1: Do ELTs’ attitudes towards the English Baccalaureate

Exam affect their teaching practices?

Descriptive analysis The statistical analysis shows that the mean of the responses for the 8 items of teachers’ AE is approximately equal to four which suggests more agreement among teachers and that they share the same attitudes toward English Baccalaureate Exam. The participants in QAE1 were asked to express their views on the English Baccalaureate Exam in terms of the exam’s intended purpose, specifically whether the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam evaluates the English knowledge and skills that 4th form students should have learned. The findings revealed that 76.1% believed that the English Baccalaureate Exam measures English knowledge and skills that 4th graders should have learned.

QAE2 and QAE3 asked the participants to express their thoughts on the impact of the English Baccalaureate Exam on their teaching practices in terms of WHAT and HOW they teach. 59.3% and 58.4% of the participants reported that the English Baccalaureate Exam respectively determined what they taught and how they taught it. Likewise, 69.9% of the respondents stated that the English Baccalaureate Exam incited them to teach to the exam.

QAE5, QAE6, and QAE7 asked the respondents about the time allocated for teaching each skill. 75.3 % of the respondents stated that they would have allocated time differently to teach each skill (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) if the English Baccalaureate Exam were cancelled. 76.1 % agreed that they were obliged to increase the amount of time spent on grammar and vocabulary. 77.8% stated that they devoted less time to teaching speaking and listening. QAE8 asked the participants whether the English Baccalaureate Exam affected the way they prepare their tests. 90.2% admitted that their tests must have the same content as the English Baccalaureate Exam. The findings from descriptive statistics revealed that the participants held both positive and negative attitudes. Most of them believed that the English Baccalaureate Exam affected the way they taught, the time allocated to different skills, and their classroom-based assessment.

ELTs’ Reported Teaching Practices

The respondents were given a series of teaching practices and asked to rate their frequency of use on a scale ranging from NEVER to ALWAYS, as well as report their teaching practices. The frequency and percentage of “Never” and “Occasionally” were categorized and estimated as one group to refer to teachers who spent 0 to 30% of class time teaching a particular skill or activity, compared to “Often,” “Usually,” and “Always” as another group to refer to teachers who spent 60 to 100% of class time teaching a particular skill or activity.

Teachers may employ a combination of techniques and strategies as long as they respect and adhere to the core communicative principles of English language teaching, and themebased content with integrated skills, which were identified by an advisory panel and deployed by teacher educators. Teachers must promote constructive learning, emphasize group work, engage learners through student-centered classrooms by integrating skills and creating a supportive climate, and provide formative feedback. The findings from descriptive statistics revealed that the majority of participants (91.6%) stated that they spent 80 to 100 % of their class time teaching the exam. They reported that the most common teaching practices that they used included providing practice and activities based on the English Baccalaureate Exam, teaching students’ strategies to answer multiple-choice questions, and teaching exam-taking skills. Non-tested skills (listening and speaking) were disregarded. The teachers focused on what might help students achieve better scores on the exam rather than developing their performance. 80% stated that they provided written production samples to their students to prepare them for the writing section. Similarly, 90% of teachers reported that they taught their students how to answer multiple-choice questions with strategies.

QTP6 and QTP10 inquired about the best time to provide and use activities and practice from previous exam papers. 30.3 % and 43 % stated that they provided and used past exam activities during lessons throughout the year. Almost 57 % of the respondents stated that they gave samples of written productions to their students to help them prepare for the writing. Approximately 62 % and 64.6 % stated that they taught their students strategies to answer multiple-choice questions, and some exam-taking strategies during the lessons throughout the year. Generally, the teachers ended up focusing on the skills and content that could help students improve their scores.

Pearson Correlation & Regression Analysis

The study aimed to check the first hypothesis whether or not there is a significant relationship between ELTs’ AE and their TPs.

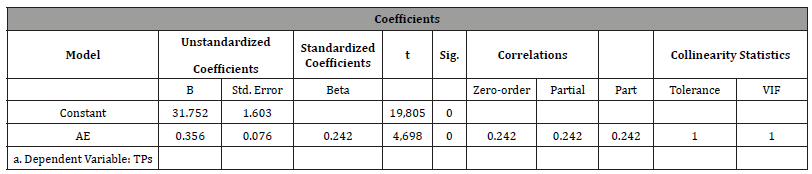

Pearson Correlation coefficient was first calculated to prove or nullify the first hypothesis that there is a relationship between AE and TPs. A significant positive correlation was found between the two variables (r (AE) and TPs =.242 p.005), indicating a significant linear relationship between them. Besides, an SLR equation was also computed to validate the positive relationship between AE and TPs. Table 4 displays the regression coefficient for the prediction of TPs and AE. Given the significance of AE, a significant regression equation was found: Y=31.752+.356(AE) (Table 4).

Table 4:Regression Coefficient for Prediction of TPs from AE.

AE has an unstandardized regression coefficient of.356; it is statistically significant (p<.05). As a result, an increase of one unit on the AE measure is expected to be accompanied by a.356-unit increase in Teaching Practices (TPs). The hypothesis that there is a significant relationship between teachers’ attitudes toward the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam and their teaching practices is supported by statistical findings. Intriguingly, AE is a statistically significant predictor of the teachers’ teaching practices.

Classroom Observation

In light of the examination of what happened in the classroom, only a few aspects of the classroom activities were examined, including the adopted method, materials—exam-related teaching materials—content—teaching skills and activities—time given to certain skills—and interaction patterns. Other aspects were not particularly important in the current study.

Generally, the four teachers did not utilize the student’s textbook. Some teachers developed their own worksheets in accordance with the high-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam, while others used their own materials in tandem with other materials prepared by their colleagues. In all the observed classes, only one teacher (T3) used the textbook only one time. When developing their handouts, the observed teachers emphasized mostly language forms (vocabulary, grammar) and content, i.e., statements, to be employed in the writing part. They disregarded the tasks and activities that were not directly related to English Baccalaureate Exam. They tailored their worksheets and activities to the requirements of the exam. To varying degrees and from time to time, the observed teachers provided their students with exam-taking strategies and tips on how to deal with the types of questions if they feature on the English Baccalaureate Exam. They devoted a lot of time to explaining how to read instructions, how to answer the different exam questions and especially how to score high. All observed teachers followed the same pattern. They usually started their lesson by introducing and practicing new words, collocations, and phrases, and they devoted the second part of the class period to teaching language forms. Besides, the most common type of interaction in the classes that were observed was Teacher-Students/Teacher Whole Class Interaction. The teacher had complete control over the content in each of these classes. The primary goal of classes was to prepare students for their exams.

Semi-Structured Interviews

To explain the findings of the quantitative analysis and from classroom observation, the data obtained from semi-structured interviews revealed that the majority of the observed teachers had mixed and contradictory feelings about the English Baccalaureate Exam, varying from negative to positive. The teachers were uncertain. On the one hand, they expressed an urgent call for the MoE, saying “we need to think again about the baccalaureate exam in general and the English exam in particular. Hence, some reforms in the syllabus and curriculum are required and must be implemented to improve the teaching of English. One of the teachers (T1) claimed that “the Bac exam should not be the only assessment tool to measure the student’s performance, because we need to add other tasks and skills like speaking, listening, and other practices”. On the other hand, they contended that “It would be too much to test listening and speaking,” and that “it is quite enough to test reading, language and writing.”

T4 expressed the pressure that they and their students underwent.

Our students themselves feel lots of pressure as they have to pass the exam. We as teachers feel the same pressure since we want our students to score high grades so that they can pursue their dream careers. The Bac exam is haunting every 4th form teacher! Even those that spot weaknesses and want to address them, feel pressured to ‘catch up with everyone else otherwise they’d be behind schedule.

Overall, their attitudes towards the exam were overwhelmingly negative and convergent. They expressed apprehension, dissatisfaction, and unease. They were dissatisfied with their teaching methodology and the feeling of being haunted by the exam. They expressed an attitude of being obsessed with exam-related activities. They felt compelled to teach to the exam to improve their students’ scores as their accountability would be measured by their students’ success.

Both quantitative and qualitative results revealed interesting findings. A statistically significant link between ELTs’ AE and their classroom TPs was found. Besides, the qualitative data analysis showed that teachers’ attitudes were mirrored in their teaching practices. They extensively used materials that they developed based on previous exam papers, activities and exam questions administered in the previous years. They placed much emphasis on language form, vocabulary, grammar, and writing, and disregarded some skills such as listening. They also showed mixed feelings about the English Baccalaureate Exam. The study aimed also to check whether there is a significant relationship between ELTs’ SREB and their TPs.

RQ2: Do ELTs’ self-reported efficacy beliefs affect their teaching practices?

Both the questionnaire and the semi-structured interview data were used to answer this question. They were used to assess the quality and self-efficacy of teachers. Teachers were asked to rate how much they agreed with each of the different self-efficacy items on a five-point Likert scale.

Descriptive Statistics

In QSREB1, 57.3 % of teachers expressed high self-confidence in teaching the English Baccalaureate Exam materials to even the weakest students. 83.4%, 84.3 %, and 78.7% of respondents said they were confident in their ability to handle any problem or unexpected situation related to exam preparation. Similarly, a higher percentage (80.9 %) reported that they were able to maintain a balance between adhering to the objectives of the syllabus and achieving the objectives of exam preparation concurrently. Only 5.6 % to 29.2% showed low self-esteem.

Pearson Correlation & Regression Analysis

To check whether their self-reported efficacy beliefs have influenced their teaching practices, the participants were asked to report their teaching practices on a frequency scale. Table 5 shows the regression coefficient for the prediction of TPs from SREB. Given the fact that SREB was significant, a significant regression equation was found: Y=13.160+.262(SREB) (Table 5).

In conclusion, the SLR was calculated to predict the participants’ TPs based on their SREB. A significant regression equation was found (F (7.690) = 7.690, p < .05), with an R2 of .021. The participants’ predicted TPs are equal to 13.160.

Semi-Structured Interviews

The interviewed teachers reported that they could handle any exam-related problems and could cover the material with even low achievers, which helped explain the quantitative findings and assess teachers’ self-efficacy. They showed high self-efficacy in dealing with unexpected situations that arose during exam preparation. Besides, they expressed confidence in their knowledge and abilities to help students believe in themselves.

T1 reported that: When the administration, the teacher educators, and students believe in you as you make good results and your own students recompense your efforts by scoring high, is motivating me, and putting some stress that pushes me to work more and more with my students.

Teachers’ perceptions of themselves and their high self-efficacy influence how they teach to the test, how they prepare students for the test using past exam papers, and how they affect their students’ learning. The teachers stated that they believed they were accountable for the success of their students. Their self-efficacy is a key factor in handling and dealing with unexpected situations related to exam preparation. They not only expressed their high selfesteem in their TPs and confidence in knowing the subject matter, but they also mentioned that they required no additional training. Their overall attitudes reflected a high sense of self-efficacy.

T1 stated: Training? It is a waste of time, Name whatever you want except training. They add nothing to me personally. I prefer to do some research, read, and attend a webinar though not all the time free to attend du Bla Bla. (a French word that means all talk for nothing).

As a novice teacher teaching 4th form for less than 5 years compared to the other teachers, T3 appeared to be less influenced by the English Baccalaureate Exam and expressed her need for continuous professional development saying:

I have been teaching Bac classes for about 3 years and it is a challenge. It is a new experience and I think I need it. It is an absolute necessity. I need more materials and training to teach Bac classes and I need to know how to make a balance between preparing students for the exam and teaching the curriculum. I, most of the time, feel worried, the scores my students get in the Bac exam reflect who I am.

To predict the participants’ teaching practices, a multiple linear regression equation was computed based on their AE and BSE. A significant regression equation was found (F = 15.324, p = .000), with an R2 of .080. The participants’ predicted TE is equal to 26.773. As AE and SREB are significant, a significant regression equation was found: Y=26.773+.356 (AE)+.262 (SREB) (Table 6).

Discussion

This paper is part of a larger study on the impact of teacherrelated factors on their teaching practices within the context of the English Baccalaureate Exam. It was intended to examine the extent to which Tunisian English language teachers’ attitudes and beliefs explain their teaching practices. Interesting results from both quantitative and qualitative analyses were found. The first objective was to examine the impact of ELTs’ attitudes towards the English Baccalaureate Exam on their teaching practices. Descriptive and inferential statistics indicated that ELTs’ attitudes had a direct, substantial impact on teacher behavior. The number of teachers who disagreed with the statements (QAE2 and QAE3) that the EBE determines what and how they teach was roughly proportional to the number who agreed. 59.3% and 58.4% agreed that the EBE respectively determines what and how they teach. Such data entails that individual variation between teachers may be the cause of the absence of uniformity and personal diversity.

It was also found that the teachers expressed mixed and contradictory feelings about the English Baccalaureate Exam, ranging from negative to positive. 76% stated that the EBE is an accurate measure of the English knowledge and skills that 4th-form students should learn. Teachers’ perceived effect of the English Baccalaureate Exam has a significant impact on how they approach teaching. The majority of respondents had a negative opinion of the English Baccalaureate Exam and how it affected “how to teach” in the classroom (70%). The respondents reported that the English Baccalaureate Exam impacted different aspects of their teaching practices in terms of their classroom assessment so that their tests must be similar to the English Baccalaureate Exam (90%), more time devoted to skills on the exam (76%) and less time to nontested skills (78%).

Results from qualitative data analysis revealed that the perceived effect of the English Baccalaureate Exam did not cause all teachers to experience the same type and intensity of washback. The finding of the present study, that teachers were haunted by the exam and subsequently were exam-oriented using the traditional methods, supports the previous findings [8,9,20,26] that assert the connection between teachers’ attitudes and their teaching practices. Besides, this finding provides more evidence that the perceived washback of the English Baccalaureate Exam and the forms it takes vary from one teacher to another and to different degrees. Teachers’ negative attitudes regarding the examination influenced various aspects of the classroom [20].

The second question in this research explored the potential existence of a relationship between ELTs’ beliefs about their selfefficacy and their teaching behavior. The participants expressed high self-esteem in teaching the materials even to the weakest students (57%) and can stick to the objectives of the syllabus and accomplish the exam preparation goals concurrently (81%). The majority were self-confident and admitted that they can usually handle any problem related to exam preparation (83%), can deal with unanticipated situations related to exam preparation (84%), and remain calm when they confront a problem related to exam preparation (79%).

The quantitative findings showed a very negligible relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and their TPs, but statistically, it is significant. Teaching experience and self-efficacy played an important role in shaping teachers’ teaching practices. The teachers’ influence varied; those who had a lot of experience teaching the 4th form of secondary education were more exam oriented. T3, who had a shorter teaching experience teaching the 4th form of secondary school seemed to be less exam oriented. She was the only one of the observed teachers who (i) used the official textbook, (ii) taught listening once, (iii) used materials developed by her colleagues, (iv) taught her class writing as a process, and (v) expressed her need for more training and continuous professional development workshops.

The significant relationship between SREB and TPs backs up the claims of researchers like Bandura [48], Gebril & Eid [9], who state that teachers with high self-efficacy are more likely to teach to the test. Generally, experienced teachers show high self-esteem, are more subjected to negative washback and act in accordance with their beliefs. Teachers with high self-efficacy, in contrast to novice teachers, are more confident, align to the requirements of the exam, and become exam slaves. However, this finding contradicts what Mashhadlou and Izadpanah [25] found about the difference between experienced and novice teachers, claiming that there was insignificant difference between experienced and novice teachers. The result also goes counter to what Nguyen and Gu [19] revealed in terms of experience, claiming that they presumed more experienced teachers approached teaching more traditionally than less experienced ones, but surprisingly, the results indicated that the more experienced the teachers were, the more communicative their methods were [49-53].

Additionally, two conflicting views from the case study data appeared. The first view is that of the novice teachers who saw the importance of the scheduled professional development and training meetings planned by the MoE. The second view is that of the experienced teachers who considered the training workshops inadequate. As teachers who had a long experience teaching the 4th form of secondary school did not believe in CPD planned by the MoE, they tended to participate in CPD less frequently, restricted themselves from updating their knowledge, reflecting, and cooperating with colleagues. For that reason, they may not receive ample training and may not have a good understanding of the objective of the curriculum and language assessment. Although ELTs have to attend pedagogic training workshops weekly, several teachers did not attend these workshops at all. Teachers’ disengagement from professional development can be explained by their personal beliefs, as well as two major facts: (i) first, there has been no rigorous, administrative follow-up in the aftermath of the Arab Spring in 2011; (ii) second, the continuous spread of the Covid-19 pandemic waves over the country put further strains on exchange and sharing among ELTs [53-58].

Conclusion and Recommendations for Future Research

The findings of the current study are significant in terms of teachers’ perceptions, self-efficacy beliefs, and language teaching practices. Teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, and teaching behaviors were found to have statistically significant relationships. Teachers’ beliefs about their self-efficacy and their attitudes towards the high-stakes English baccalaureate exam both predict their teaching practices. Given the fact that teachers’ cognition-attitudes and beliefs have an impact on their teaching practices, modifying teachers’ cognition is highly recommended to achieve the ultimate goals of the national curriculum of teaching English. Teachers play a significant role in determining the washback effect and are responsible for helping students learn English and prepare them for the English Baccalaureate Exam, they should be trained to strike a balance between their beliefs and preferences and the requirements and scope of the English curriculum, so that they can adapt their practices accordingly. Hence, examining and understanding what teachers believe helps policymakers set up appropriate and efficient policies. Nevertheless, the process of modifying and changing teachers’ beliefs requires both time and careful planning. Therefore, continuous professional development is required to assist teachers in reflecting on their current teaching and assessment practices and developing positive attitudes and action plans so that they become more effective. Regardless of the training that the MoE plans, an open-bottom-up debate particularly about language testing and teacher assessment literacy is still needed and should be designed to motivate teachers to participate in and learn how to prepare their students for the English Baccalaureate Exam without generating negative washback [59-62].

The current study does have some limitations, some of which are primarily methodological and others which are due to time constraints. Only factors specific to teachers were taken into account. Other variables may have been considered, such as the quality of the design of the test, social and educational contexts, and students’ roles, etc. The current research did not address the topic from other participants’ perspectives [63-66].

In view of the findings, understanding and modifying teachers’ attitudes and beliefs will lead to improved teaching practices. Future research may examine other factors such as learners’ perceptions and learning strategies, and the school environment that can help improve English language teaching and can influence teachers’ teaching behavior [67-69].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Booth DK (2018) The sociocultural activity of high stakes standardized language testing TOEIC washback in a South Korean context. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Shohamy E (2014) The power of tests: A critical perspective on the uses of language tests. London: Longman.

- Shohamy E (2017) Critical language testing. In Elana Shohamy, Iair G. Or & Stephen May (Eds.) Language testing and assessment, (pp. 1-15). UK: Springer International Publishing.

- Bachman LF, Palmer AS (2002) Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brown HD (2004) Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

- Messick S (1989) Validity. In Robert L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement. (pp. 13-103). New York: American Council on education and Macmillan.

- Weir CJ (2005) Language testing and validation: An evidence-based approach. Houndgrave, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Ahmed AAM (2018) Washback: Examining English language teaching and learning in Libyan secondary school education. (Ph.D dissertation). University of Huddersfield, United Kingdom.

- Gebril A, Eid M (2017) Test preparation beliefs and practices in a high-stakes context: A teacher’s perspective. Language Assessment Quarterly 14(4): 360-379.

- Borg S (1998) Teachers’ pedagogical systems and grammar teaching: A qualitative study. TESOL Quarterly 32(1): 9-38.

- Borg S (2003) Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching 36: 81–109.

- Borg S (2005) Teacher Cognition in Language Teaching. In Keith Johnson (ed.), Expertise in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 190-209. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tsagari D (2011) Washback of a high-stakes English exam on teachers’ perceptions and practices, 431-445. Selected Papers from the 19th International Symposium on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, pp. 431-445.

- Wall D (2000) The impact of high stakes testing on teaching and learning: Can this be predicted or controlled? System 28: 499-509.

- Cross Francis DI (2014) Dispelling the notion of inconsistencies in teachers’ mathematics beliefs and practices: A 3-year case study. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education 18(2): 173–201.

- Roose I, Vantieghem W, Vanderlinde R, Van Avermaet P (2019) Beliefs as filters for comparing inclusive classroom situations. Connecting teachers’ beliefs about teaching diverse learners to their noticing of inclusive classroom characteristics in videoclips. Contemporary Educational Psychology 56: 140–151.

- Pajares MF (1995) Self-efficacy in academic settings. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, April p.18-22.

- Estaji M, Alikhani H (2020) The First Certificate in English Textbook Washback Effect: A Comparison of Teachers' and Learners' Perceptions.

- Nguyen H, Gu Y (2020) Impact of TOEIC listening and reading as a university exit test in Vietnam. Language Assessment Quarterly 17(2): 147–167.

- Rahman KA, Seraj PMI, Hasan MK, Namaziandost E, Tilwani SA (2021) Washback of assessment on English teaching-learning practice at secondary schools. Language Testing in Asia 11(1).

- Hartaty W (2017) The impacts of the 2015 national examination policy in Indonesia on English language teaching. Proceedings of the Fifth International Seminar on English Language and Teaching (ISELT-5), pp.355-358.

- Gunn J, Al-Bataineh A, Abu Al-Rub M (2016) Teachers’ perceptions of high-stakes testing. International Journal of Teaching and Education 4(2): 49-62.

- Kagan DM (1990) Ways of evaluating teacher cognition: Inferences concerning the goldilocks principle. Review of Educational Research 60(3): 419-469.

- Ortaçtepe D, Akyel AS (2015) The Effects of a professional development program on English as a foreign language teachers’ efficacy and classroom practice. TESOL Journal 6(4): 680–706.

- Mashhadlou H, Izadpanah S (2021) Assessing Iranian EFL teachers’ educational performance based on gender and years of teaching experience. Language Testing in Asia 11(23): 1-26.

- Al Amin M, Greenwood J (2018) The examination system in Bangladesh and its impact: on curriculum, students, teachers, and society. Language Testing in Asia, 8(1).

- Choi E, Lee J (2017) EFL teachers’ self-efficacy and teaching practices. ELT Journal 72(2): 175–186.

- Koizumi R (2022) L2 Speaking Assessment in Secondary School Classrooms in Japan. Language Assessment Quarterly 19(2): 142-161.

- Hartell E (2018) Teachers’ Self-efficacy in assessment in technology education. In MJ de Vries (Ed.), Handbook of Technology Education, pp. 785–800.

- Mirmojarabian MS, Rezvani E (2021) EFL teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and their (non)-communicative instructional practices. In TEFLIN Journal 32(2): 267- 294.

- Jäger D, Merki K, Oerke B, Holmeier M (2012) Statewide low-stakes tests and a teaching to the test effect? An analysis of teacher survey data from two German states. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 19(4): 451–467.

- Shahzad K, Naureen S (2017) Impact of Teacher Self-Efficacy on Secondary School Students’ Academic Achievement. Journal of Education and Educational Development 4(1): 48-72.

- Rao X (2018) University English for Academic Purposes in China a Phenomenological Interview Study. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. and Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press.

- Al-Khatib MA (2008) Innovative second and foreign language education in the Middle East and North Africa. In Nelleke Van Deusen-Scholl & Nancy H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, 2nd edition, volume 4: Second and foreign language education (pp. 227–37).

- Battenburg J (2006) Tunisia: Language Situation. 145-146.

- OECD (2015-2016) Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Bouhlila DS (2021) Education in Tunisia: Past progress, present decline, and future challenges.

- Boukadi S, Troudi S (2017) English Education Policy in Tunisia, Issues of Language Policy in Post-revolution Tunisia. In Robert Kirkpatrick, (Ed.), English Language Education Policy in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 257–277). Springer International Publishing AG.

- Cherif MC (2022) 10 Reasons Why the Tunisian Education System Desperately Needs Reform. In Carthage Magazine.

- Messick S (1996) Validity and washback in language testing. Language Testing 13(3): 241–256.

- Bouhouch H, Akrout M (2014) The Tunisian Baccalaureate 2014.

- Athimni M, Labben A (2015) Revisiting the Tunisian Baccalaureate: Between a changing educational policy and historical stagnation. A conference paper presented at EALTA 2015 Policy and Practice in Language Testing and Assessment.

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW (1970) Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30: 607-610.

- Ruel E, Wagner WE, Gillespie BJ (2016) The Practice of Survey Research Theory and Applications. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Hair Jr JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2019) Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th Publisher: Annabel Ainscow.

- Kiger ME, Varpio L (2020) Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher 42(8): 846-854.

- Cohen C, Manion, L, Morrison K (2018) Research methods in education (8th ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

- Bandura A (1994) Self-Efficacy. In Vilayanur S Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Human Behavior 4: 71-81.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewoods Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Basturkmen H (2012) Review of research into the correspondence between language teachers’ stated beliefs and practices. System 40: 282-295.

- Binnahedh IB (2022) E-assessment: Wash-Back Effects and Challenges (Examining Students’ and Teachers’ Attitudes Towards E-tests). Theory and Practice in Language Studies 12(1): 203-211.

- Copp DT (2019) Accountability testing in Canada: Aligning provincial policy objectives with teacher practices. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy 188: 15-35.

- Copp DT (2018) Teaching to the test: a mixed methods study of instructional change from large-scale testing in Canadian schools. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 25(5): 468–487.

- Creswell JW, Plano VC (2018) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Dhaoui I (2015) Efficiency of the Tunisian education system: Analyses et perspectives. Note et Analyses de l’ITCEQ,29.

- Farrell TSC, Ives J (2015) Exploring teacher beliefs and classroom practices through reflective practice: A case study. Language Teaching Research 19(5): 594-610.

- Fish J (1988) Responses to mandated standardized testing. (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation), University of California, Los Angeles

- Gökhan Ö (2015) Language teacher cognition, classroom practices and institutional context: A qualitative case study on three EFL teachers. (PhD dissertation). Middle East Technical University, Turkey.

- Hughes A (2003) Testing for language teachers. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lam HP, Ki CS (1995) Methodology washback- an Insider's view. In D. Nunan, Berry R, & Berry V. (Eds.), Bringing about changes in language education: Proceedings of the International Language in Education Conference 1994 (83-102). Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Department of Curriculum Studies.

- Read J, Hayes B (2003) The impact of IELTS on preparation for academic study in New Zealand. IELTS International English Language Testing System Research Reports 4: 153-206.

- Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhi A (2016) Research methods for business students. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- Tavakoli M, Baniasad-Azad S (2016) Teachers’ conceptions of effective teaching and their teaching practices: a mixed-method approach. Teachers and Teaching 23(6): 674–688.

- (2018) TfST Teaching for Success, Tunisia.

- Tsagari K (2006) Investigating the washback effect of a high-stakes EFL exam in the Greek context: Participants’ perceptions, material design and classroom applications. (PhD dissertation). Lancaster University, UK.

- Wisdom S (2018) Teachers’ perceptions about the influence of high stakes testing on students. (Doctor of Education project study). Walden University, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States.

- Xie Q (2013) Does Test Preparation Work? Implications for Score Validity. Language Assessment Quarterly 10(2): 196–218.

- Xie Q (2015) Do component weighting and testing method affect time management and approaches to test preparation? A study on the washback mechanism. System 50: 56–68.

- Yaagoubi M, Talbi S, Laamari S, Ben Slimane R (2013) Analysis of the Tunisian education system.

-

Hanen Dammak*, Ali Khatibi and SM Ferdous Azam. Tunisian English Language Teachers’ Attitudes and Self-Reported Efficacy Beliefs: Washback of the High-Stakes English Baccalaureate Exam. Iris J of Edu & Res. 1(3): 2023. IJER.MS.ID.000512.

-

Washback, Attitude, High-stakes English Baccalaureate Exam, Self-reported efficacy beliefs, Literature Review, Secondary Education Certificate Examination, Multiple-choice questions

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.