Case Report

Case Report

From An Individual-Medical Perspective to Participation – Considerations on Special Education Assessment in the Field of Physical and Motor Development in Germany

Traugott Böttinger*

Department of Special Education with focus on inclusive education, University of Education Freiburg, Germany

Traugott Böttinger, Department of Special Education with focus on inclusive education, University of Education Freiburg, Germany

Received Date: December 14, 2025; Published Date:December 19, 2025

Abstract

The article looks at the special educational needs assessment procedure in the German school system in the field of physical and motor disabilities as part of an analysis of assessment reports. The inclusion of the bio-psycho-social model of disability within the framework of the ICF and ICF-CY,which relates the individual-medical model of disability and the social model of disability to each other, is considered central. However, the analysis shows that the individual-medical model is particularly influential, and that deficit-oriented perspectives on students and their impairments or disorders are predominant. In addition, specific aspects of learning and education for students with physical disabilities tend to be considered rather superficially. In this context, the assessment procedure serves much more to assign students to certain types of schools than to describe students’ learning development to help take individual learning progress into account in the classroom.

Keywords: Special educational need; Assessment; ICF; Participation; Physical and Motor Disability

Abbreviations:SEN: special educational needs; KMK: Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (Kultusministerkonferenz); UN: United Nations; ICF-CY: International classification of functioning, disability and health - children and youth)

Introduction

Critical Aspects of the Special Education Assessment in Germany

The process of assessing special educational needs (SEN) has always had a significant impact on biographies of students in Germany. From a historical perspective, until the 1970s, a disability could lead to exclusion from compulsory schooling, as school laws (e.g., in Baden-Württemberg from 1976) contained provisions regarding the inability of disabled children and young people to attend school. The question of inclusive schooling also had a clear answer: Students with SEN were automatically placed in different special education programs within special schools, e.g., for intellectual or physical and motor disabilities. Although there are different milestones regarding school development in Germany in the last 20 years (e.g., KMK recommendations on SEN 1994, ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2009, and KMK recommendations on inclusive education for children and young people with disabilities in schools 2011) [1-3], and now there is a focus on inclusive education in the German school system, it still follows the different special educational needs.

Despite the only purpose of the SEN assessment is no longer to select and assign students to different types of schools but to analyse learning requirements and to provide learning support [4] and despite there is a stronger focus on biological, psychological and social factors according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [5], criticism of the assessment procedure has been mounting in recent years. Among other things, the criticism relates to (a) the continuously rising number of students with SEN [6,7], (b) the reinterpretation of complex problem constellations in the context of institutional discrimination as individual problems [8], (c) the strong focus on a deficit-oriented view of students with SEN [9], or (d) the different roles taken by teachers in the assessment process [10].

From a teaching perspective, there is another difficulty to consider in both segregated and inclusive school settings: special education assessments make almost no contribution to supporting students with SEN in the classroom and everyday school life, as the learning environment is given little consideration. This thesis is explored below through the analysis of five SEN assessment reports focusing on students with physical and motor disabilities. The analysis serves as a preliminary step for a more extensive research project on the SEN assessment, which will begin in 2026.

Case Presentation

Special Education Assessment in the Field of Physical and Motor Disabilities

SEN assessment fulfils two functions in the German school system [11]: On the one hand, they form the basis for decisions on school organization, for example, regarding the assignment of students to different special schools or the provision of additional resources in inclusive schools. Second, as a formative assessment tool, it is intended to show students’ learning development and help to take individual learning progress into account in the classroom.

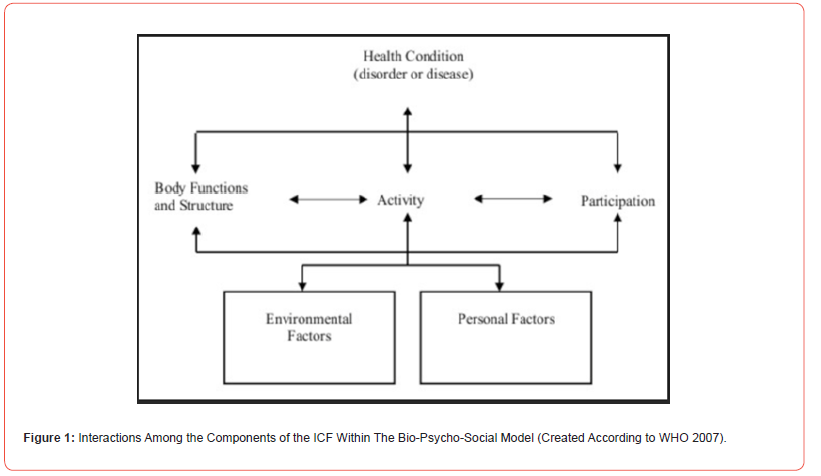

For implementation, reference to the ICF and the ICF-CY (Children and Youth) with a focus on specific developmental processes in childhood and adolescence has proven useful [12,13]. The ICF’s bio-psycho-social model [14,15] combines the individualmedical model of disability (disability as an individual impairment or disorder, e.g., due to a genetic defect) and the social model of disability (disability as a social construct arising from barriers in society, with the reaction of the environment and the individual’s ability to adapt being central). For physical and motor disabilities, the focus is on the interaction between physical impairment and social context factors, as SEN can also arise at the levels of (limited) activity and participation.

An example illustrates the structure of the ICF model (Figure 1): Infantile cerebral palsy is one of the most common physical and motor disabilities [16]. This sensomotoric disorder is caused by early childhood brain damage and leads to impaired interaction between sensory and motor functions in the reception, processing, and transmission of stimuli to muscle cells [17]. The movement disorder has an impact on body functions and body structures, e.g., due to limited mobility a student needs a wheelchair to cover longer distances (activity). Individual actions (e.g., moving from the classroom to the schoolyard) and, as a result, participation as involvement in different life situations may therefore be limited. However, a wheelchair can only be used effectively in an accessible school building with appropriate school equipment (environmental factors). Depending on the age of the student or the personal ability to move around in a wheelchair, the support of another person may also be necessary (personal factors). At the same time, personal factors, which may also include intact body functions, must be considered as resources for activities. The aim is to enable activities to be carried out as independently as possible by analysing barriers to participation and support needs. Since this focus on participation is also central to the school context, the ICF-CY can be used in the context of the SEN assessment [18,19].

Central to physical and motor disabilities is the individual examination of physicality and a specific experience of spatial perception and social interaction, which are caused by an impairment or disorder (e.g., spina bifida, asthma, dysmelia), comorbidities (e.g., speech disorders), and secondary impairments (e.g., difficulties with eating and drinking). Within the framework of the ICF, the areas of learning and applying knowledge (d1), communication (d3), mobility (d4), self-care (d5), and interpersonal interactions and relationships (d7) are particularly significant [11]. Overall, SEN assessments in the field of physical and motor disability should relate three aspects to each other: (a) the student´s individual physical condition, (b) the tasks to be completed at school with their specific requirements, and (c) the learning environment (ibid., p. 157).

Description and Analysis of Assessment Reports

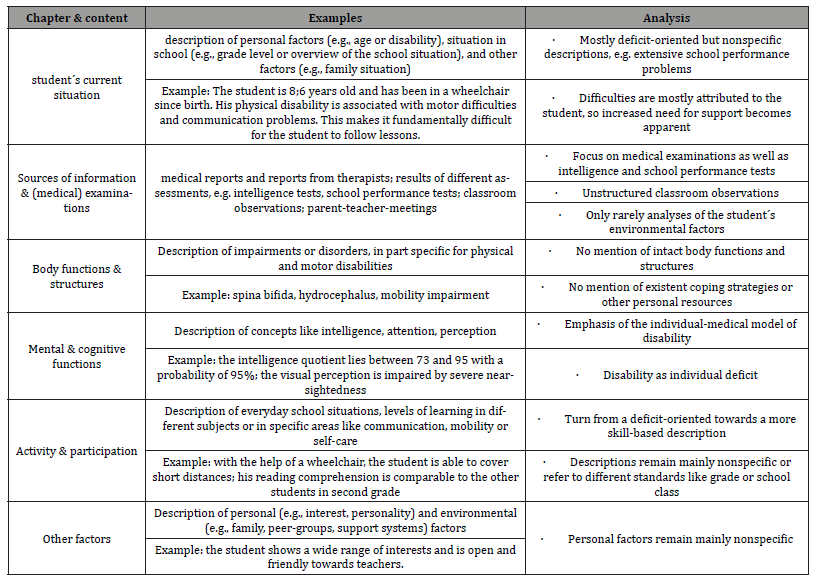

All assessment reports answer the same question, namely whether a primary school student (in most of the federal states in Germany this refers to grades 1 to 4) should be diagnosed with SEN. The organization and implementation of SEN assessments vary across the federal states in Germany [20,21] and thus also the content of the assessment reports. Since the analysed assessment reports all come from one federal state, they are comparable in terms of their structure (Table 1). In all five reports, SEN with focus on physical and motor development was recommended.

Table 1:Description and Analysis of the Assessment Reports.

The analysis in table 1 needs to be specified by further aspects. The SEN assessment reports show a clear medical focus against the backdrop of the students’ physical impairments. The medical model of disability proves to be particularly influential, while the social model of disability, or the view of disability as a social and cultural construct, is nearly non-existent. Although reference is made to the ICF and the model described above, the focus is predominantly on limited body functions and structures as well as mental/cognitive abilities. This would be unproblematic if this view were accompanied by an analysis of the structures and barriers that cause disability and a detailed consideration of participation and activities. However, this is largely missing from the reports analysed. Furthermore, the assessment reports contain only a few statements about the student’s biography or life outside of school or about specific opportunities for individual development, as the deficit-oriented descriptions take up a lot of space. Specific teaching or classroom situations are usually described in a non-specific and, above all, deficit-oriented manner and rarely contain a description of specific learning behaviour. For students with physical and motor disabilities, specific factors influencing learning behaviour can be described: brain development, motor development, cognitive and linguistic development, development of executive functions, opportunities for social participation, and opportunities to be an agent of their own development [22]. Overall, there is a very wide range of learning behaviours, which makes it nearly impossible to make an SEN assessment without structured observations specific to the situation in the classroom. A direct link between physical impairment and reduced intelligence cannot be assumed; rather, factors such as working memory, attention span, memory capacity, self-regulation, and learning strategies must also be considered (ibid., p. 71). Finally, the student’s social environment is said to be very important for support (ibid., p. 72). All these points play a subordinate role in the assessment reports. It becomes apparent that only the individual physical condition of the student is given sufficient attention in a deficit-oriented way, while too little attention is paid to the tasks to be completed at school as well as the learning environment.

The analysis shows that assessment reports primarily fulfil the first function of special education diagnostics, namely the assignment of students to different special schools or the provision of additional resources in inclusive schools. The second function, to show students’ learning development and to help to take individual learning progress into account in the classroom, often is considered very little. What change of perspective could help that the second function, which is of much greater importance to the students than the first one, can also be fulfilled?

Greater emphasis should be placed on the individual circumstances of each student. This involves not only describing individual deficits and impairments, but also analysing the family and social environment or educational background to identify support systems and aspects of successful participation and involvement. The same applies to teaching itself: in which situations can students contribute their skills, abilities and talents? What characterizes these situations? However, this is only possible if disability is considered a social construct: in which situations the disability results of an impairment or disorder, in which situations the student is disabled by barriers? How can these situations be described? It may be helpful to take a more in-depth look at the ICF and the areas that are important for physical and motor disabilities, such as mobility, communication, or self-care (see above).

Discussion”

The SEN assessment process is complex and, in times of teaching staff shortage in Germany, presents various challenges [23]. Even this brief analysis of five assessment reports provides initial indications that the current assessment approach is missing an opportunity to use the process not only as a means of structuring and assigning students within the school system, but also to incorporate the findings into school and teaching development adapted to individual students, e.g., in the context of didactic and methodological decisions to create learning environments that are as barrier-free and individually fitting as possible. The focus should be on participation, as well as on opportunities for the student’s education, rather than primarily on ways of compensating for disabilities within the framework of the individual-medical model of disability. These are undoubtedly necessary within the framework of the assessment but overemphasizing them is not very effective. However, individual education plans for students show that this is often the case in the SEN assessment process. They are usually characterized by deficit-oriented and nonspecific descriptions and loosely fitting support measures [24]. But especially these individual education plans could be an opportunity to implement special education and respond more deeply to individual life situations and learning needs. For the field of physical and motor disability, dealing with changes in physicality is also central, therefore aspects such as identity/self-image, independent living, communication, and learning need to be addressed. The ICF and ICF-CY provide a good starting point here.

It should be noted that the analysis of five SEN assessment reports is by no means representative. It must also be taken into account that the assessments vary greatly due to the different requirements of the federal states [20], the individual administrative districts, and, last but not least, the school authorities. Therefore, the present analysis is intended to raise awareness of the issue and refer to an upcoming comprehensive analysis of more than 100 assessment reports form different SEN programs and administrative districts. The focus is on the question of whether the results can be reproduced or transferred to other areas of special education. For this small pretest, it can be noted that the central results correspond with analyses of assessment reports by other authors [25,26].

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- KMK – Kultusministerkonferenz (2011) Inklusive Bildung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Behinderungen an Schulen. Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom.

- KMK – Kultusministerkonferenz (1994) Empfehlungen zur sonderpädagogischen Förderung in den Schulen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom.

- UN – United Nations (2009) Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities.

- Kornmann R (2018) Von der Auslesediagnostik zur Förderdiagnostik: Entwicklungen, Konzepte, Probleme. In FJ Müller (Hrsg.). Blick zurück nach vorn – WegbereiterInnen der Inklusion. Band 1. Psychosozial Verlag S. 207-226.

- WHO – World Health Organization (2007) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – Children & Youth Version. WHO Press.

- Lepper C, Steinmann V (2024) Status Quo: Inklusion an Deutschlands Schulen. Schuljahr 2022/2023. Factsheet der Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Scheer D, Melzer C (2020) Trendanalyse der KMK-Statistiken zur sonderpädagogischen Förderung 1994 bis 2019. - In Zeitschrift für Heilpädagogik 11: 575-591.

- Adl-Amini K, Gasterstädt J, Kistner A, Klenk FC, Kadel J et al. (2025) Inklusive Diagnostik in Verfahren zur Feststellung sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarfs? Zwischen angemessener Förderung und institutioneller Diskriminierung (InDiVers). In K Beck, RA Ferdigg, D Katzenbach, J Kett-Hauser, S Laux, M Urban (Hrsg.). Förderbezogene Diagnostik in der inklusiven Bildung. Professionalisierung – spezifische Unterstützungsangebote – Übergänge in die berufliche Bildung. Waxmann S. 43-63.

- Galeano Weber E, Aissa R, Moser V, Hasselhorn M (2025) Determining special educational needs in Germany: Current status and the coherence of the rationale of support recommendations. European Journal of Special Needs Education, online first.

- Gasteiger-Klicpera B, Buchner T, Hoffmann M, Hoffmann T, Proyer M (2025) Evaluierung der Vergabepraxis des sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarfs (SPF) in Österreich: Diskussion der zentralen Ergebnisse. In E Besic, D Ender, B Gasteiger-Klicpera (Hrsg.). Resilienz.Inklusion.Lernende.System. Verlag Julius Klinkhardt S. 281-289.

- Thiele A, Erdmann A, Hammer-Schmitt V, Höglinger K (2025) Diagnostik in der inklusiven Schule – Perspektiven aus dem Schwerpunkt Körperlich-motorische Entwicklung. In A Thiele (Hrsg.). Pädagogik und Didaktik bei körperlich-motorischer Beeinträchtigung. Fachliche Expertise für die schulische Inklusion. Kohlhammer S. 149-165.

- Bosse I (2022) Diagnostik und Förderplanung mit Assistiven Technologien (AT) auf Grundlage der ICF?! In M Gebhardt, D Scheer, M Schurig (Hrsg.), Handbuch der sonderpädagogischen Diagnostik: Grundlagen und Konzepte der Statusdiagnostik, Prozessdiagnostik und Förderplanung. Regensburg: Universitätsbibliothek S. 97–110.

- Kölbl S (2025) ICF-CY im sonderpädagogischen Schwerpunkt Geistige Entwicklung. Ein Praxisleitfaden zur Beobachtung und Dokumentation. Hogrefe.

- Pretis M (Hrsg.) (2022) ICF-basierte Gutachten erstellen. Entwicklung im interdisziplinären Team. Reinhardt Verlag.

- Rauner R, Stecher M (2021) Die ICF-CY als Qualitätsleitplanke sonderpädagogischen Handelns im Kontext Schule. In Sonderpädagogische Förderung heute 4: 408-417.

- Moosecker J (2020) Förderschwerpunkt körperliche und motorische Entwicklung. In U Heimlich, E Kiel (Hrsg.). Studienbuch Inklusion. Ein Wegweiser für die Lehrerbildung. Julius Klinkhardt S. 55-72.

- Bergeest H, Boenisch J (2019) Körperbehindertenpädagogik. Grundlagen – Förderung – Inklusion. 6.Auflage. UTB.

- Bernasconi T (2022) ICF‐orientierte Förderplanung. In M Gebhardt, D Scheer, M Schurig (Hrsg.). Handbuch der sonderpädagogischen Diagnostik. Grundlagen und Konzepte der Statusdiagnostik, Prozessdiagnostik und Förderplanung. Regensburg: Universitätsbibliothek S. 733‐748.

- Hollenweger J (2019) ICF als gemeinsame konzeptuelle Grundlage. In: R. Luder, A. Kunz & C. Müller Bösch (Hrsg.), Inklusive Pädagogik und Didaktik Bern: hep S. 30‐54.

- Gasterstädt J, Kistner A, Adl-Amini K (2020) Die Feststellung sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarfs als institutionelle Diskriminierung? Eine Analyse der schulgesetzlichen Regelungen. In Zeitschrift für Inklusion.

- Steinmetz S, Wrase M, Helbig M, Döttinger I (2021) Die Umsetzung schulischer Inklusion nach der UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention in den deutschen Bundesländern. Nomos Verlag.

- Boenisch J (2025) Besonderheiten im Lernverhalten von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Beeinträchtigungen der körperlichen und motorischen Entwicklung. In A. Thiele (Hrsg.). Pädagogik und Didaktik bei körperlich-motorischer Beeinträchtigung. Fachliche Expertise für die schulische Inklusion. Kohlhammer S. 65-81.

- Dworschak W, Kölbl S (2020) Mobile Sonderpädagogische Dienste (MSD). In U Heimlich, E Kiel (Hrsg.). Studienbuch Inklusion. Klinkhardt Verlag S. 158-166.

- Borel S, Adl-Amini K, Gasterstädt J, Kistner A (2025) Förderpläne in der schulischen Praxis. Eine Analyse im Kontext der Feststellung sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarfs. In Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung 18: 33-48.

- Hennes AK, Philippek J, Dortants L, Abel M, Baysel et al. (2024). Sonderpädagogische Diagnostik im Feststellungsprozess: Eine Ist-Stand-Analyse und der Blick nach vorn. In Zeitschrift in Heilpädagogik 7: 288-302.

- Nideröst M, Röösli P, Hövel D, Behringer N, Hennes et al. (2024) Prädestination sonderpädagogischer Gutachtenerstellung? Eine empirische Untersuchung von Gutachten aus dem Förderschwerpunkt Emotionale und Soziale Entwicklung. In Emotionale und soziale Entwicklung in der Pädagogik der Erziehungshilfe und bei Verhaltensstörungen 6: 34-55.

-

Traugott Böttinger*. From An Individual-Medical Perspective to Participation – Considerations on Special Education Assessment in the Field of Physical and Motor Development in Germany. Iris J of Edu & Res. 6(1): 2025. IJER.MS.ID.000626.

-

Special educational need, Assessment, ICF, Participation, Physical and motor disability

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Language Representation in the Brain

- What are the Cognitive and Neural Consequence of Bilingualism?

- Developmental Changes across Lifespan in Bilingualism

- Neuroimaging Tools to Study Bilingualism

- Language Experience and Neuroplasticity

- Conclusion and Future Direction

- Acknowledgment

- Conflict of Interest

- References