Short Communication

Short Communication

Black Urban Storytelling: A Personalized Len on Black Experiences

Shanice Robinson Blacknell*

The Graduate College of Education and College of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University, USA

Shanice Robinson Blacknell, The Graduate College of Education and College of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University, USA

Received Date:March 22, 2024; Published Date:April 01, 2024

Abstract

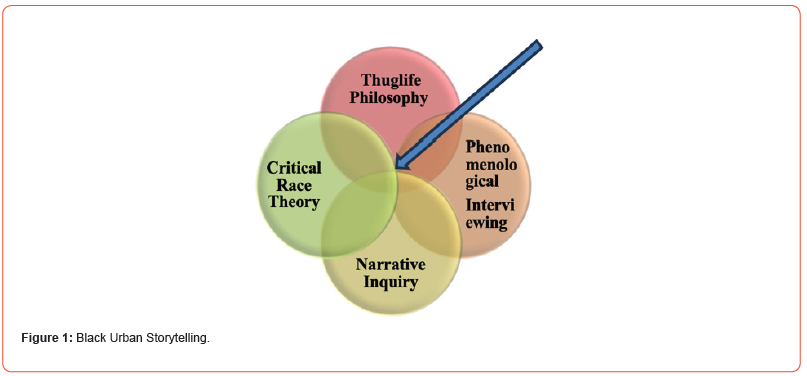

This scholarly article introduces the Black Urban Storytelling (BUS) framework, a conceptual tool devised to address the inherent limitations of Critical Race Theory (CRT) in capturing the nuanced array of Black experiences. The framework, enriched by the integration of Tupac Shakur’s Thug Life philosophy, emanates from an extensive scholarly inquiry, forming the core of my investigation into the successful navigation of Black men escaping the school-to-Prison Pipeline (STPP). This study challenges prevailing misconceptions surrounding the perceived inescapability within the STPP paradigm. Beyond the scope of my dissertation, this article advocates for the broader application of the BUS framework, positioning it as a valuable analytical instrument in higher education and societal contexts. The argument is grounded in the framework’s efficacy in scrutinizing the multifaceted experiences of Black males while extending its scope to encompass the experiences of females within 4-year institutions. The BUS framework presents a distinctive opportunity to capture data on communal experiences that are often overlooked, facilitating examinations into anxiety, depression, microaggressions, and the profound impact of white educators’ perspectives on Black students. This article underscores the scholarly-practitioner perspective, emphasizing the framework’s potential to inform both academic discourse and practical interventions for a more inclusive and equitable educational environment.

Keywords:Black Urban Storytelling; Black Community; Critical Race Theory; Thuglife Philosophy; School-to-Prison Pipeline

Introduction

The Black Urban Storytelling (BUS) framework, originating from my doctoral research, serves as a sophisticated analytical instrument developed during an exploration of how three formerly incarcerated Black males successfully navigated the school-to- Prison Pipeline (STPP). This article endeavors to extend the framework’s scope by investigating and incorporating pillars that address the higher education experiences of both Black males and females, focusing specifically on challenges such as deficit thinking, imposter syndrome, microaggressions, anxiety, and more. The foundational pillars—Bouncing Back, Humanizing Black Identity, and Resisting Oppression—initially identified during the dissertation research, provide the structural basis for the framework’s expansion into the realm of higher education.

The BUS framework, influenced by Critical Race Theory (CRT), diverges from traditional CRT narratives by incorporating diverse media forms and infusing Tupac Shakur’s Thug Life philosophy. This innovative approach enriches understanding of the persistent systemic challenges confronting the Black community [1,2]. BUS facilitates communication and comprehension of the nuanced realities of Black Americans, highlighting the importance of race and racism in societal analysis. Drawing from Crenshaw’s [3] work on intersectionality, BUS provides a powerful lens for examining the higher education experiences of Black males and females. This framework illuminates the overlap between theoretical constructs and everyday life for college students.

The development of BUS emerged from a critical need to address gaps in existing literature, particularly the limitations of traditional CRT storytelling in addressing oppressive practices against Black men. By incorporating Tupac Shakur’s Thug Life philosophy, this framework constructs pillars such as The Bounce Back, Humanizing Black Male Identity, and Resisting Oppression, which offer a comprehensive understanding of participants’ experiences [1]. Contrary to traditional storytelling that predominantly legitimizes the experiences and narratives of marginalized communities, contemporary Black storytelling takes a more proactive role in giving voice to the Black community, challenging existing narratives, and striving for empowerment [4]. In the context of this research, storytelling became a critical tool for understanding the disproportionate application of ZTPs to Black students in low-income communities, shedding light on the harsh realities they face due to punitive disciplinary measures [5,6]. Thus, while CRT remains foundational, contemporary conceptual frameworks like BUS are essential for fully encapsulating the Black experience in America.

Thug Life Philosophy

Shakur posited Thug Life as more than an acronym but a symbol representing the struggles and resilience of the Black community. “The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody” encapsulated Shakur’s belief in systemic injustices’ enduring impact on Black individuals from youth. Shakur’s life reflected the tension between his revolutionary ambitions, influenced by his second-generation Black Panther background, and his affiliation with the thug lifestyle amidst a changing sociopolitical landscape. Critics, such as Dyson [7], raised concerns over Shakur’s glorification of Thug Life, linking it to a perceived decline rooted in the Black Panthers’ legacy. However, Dyson [7] acknowledged Shakur’s perspective, were Thug Life extended Black Panther beliefs in self-defense and class rebellion. Shakur viewed education as a means of self-defense against bigotry and emphasized Black pride not as therapy but as a means of cultivating self-respect, extending to respecting others. Thug Life symbolized resistance, pride, and resilience against societal inequalities.

Shakur’s interpretation of Thug Life resonates with formerly incarcerated Black individuals navigating higher education to reclaim their lives. Thug Life serves as a source of empowerment and resilience for current Black college students from similar backgrounds, offering a framework for overcoming past incarceration, poverty, dysfunctional family dynamics, and unmet educational needs. Shakur’s legacy remains intertwined with societal struggles, maintaining relevance as long as marginalized communities endure hardship. Notably, Shakur’s observations on the rampant incarceration of Black men underscore ongoing discussions on racial disparities within the criminal justice system. As Dyson [7] notes, Black mythologies like Thug Life are challenging to establish and sustain in broader societal contexts, indicating the enduring relevance of Shakur’s philosophy.

The proposed framework serves as a culturally responsive and transformative tool for formerly incarcerated students, extending its utility beyond K-12 education to support their collegiate endeavors. By providing a platform for individuals to refine their narratives and destigmatize their identities as formerly incarcerated, this framework offers a significant avenue for empowerment and growth. Designed with a specific focus on amplifying the voices and lived experiences of Black men and women, this analysis ensures cultural responsiveness to their unique perspectives. Through the utilization of linguistic vernacular rooted in the Black dialect (Williams, 1972) and drawing from cultural experiences, individuals are empowered to articulate systemic and interpersonal inequities they have encountered or witnessed.

Utilizing the BUS framework, individuals harness their voices as tools for advocacy and resistance. By sharing their stories, they not only highlight their struggles but also shed light on the support systems and successes they have experienced. This practice not only serves as a means of self-expression but also as a mechanism for driving positive change within and beyond the prison system. Ultimately, the simplicity yet potency of BUS empowers individuals to advocate for the changes they envision, benefiting not only themselves but also others seeking transformation within the criminal justice system and broader society [8].

Contextualizing the Three Themes

Three themes emerged from the BUS and Thug Life Philosophy

framework, demonstrating integral aspects through the funneling

of directed participant responses. These themes can play a crucial

role in understanding both the Black college students’ engagement

with and their successful navigation away from the STPP. Following

the exposition of the participants’ experiences, the chapter presents

the research findings, organized into three themes:

• The Bounce Back

• Humanizing Black Identity

• Resisting Oppression

Firstly, “The Bounce Back” theme encapsulates resilience, highlighting the capacity of individuals to rebound from adversities encountered on their educational journey. This resilience empowers students to overcome challenges, persist in their pursuit of academic success, and defy the odds stacked against them. Secondly, “Humanizing the Black Identity” sheds light on the importance of dismantling stereotypes surrounding Black masculinity. By affirming the diverse identities of Black male students, this theme fosters a sense of belonging and agency within academic environments, enabling individuals to navigate higher education with confidence and self-assurance. Lastly, “Resisting Oppression” underscores the proactive stance taken by students in challenging systemic injustices and advocating for institutional change. By confronting oppressive structures and policies, individuals assert their rights and demand equitable treatment, paving the way for a more inclusive and supportive educational landscape.

These themes serve as guiding pillars for formerly incarcerated Black male and female college students, offering pathways toward academic success and social empowerment. By embracing resilience, affirming their identities, and challenging oppressive systems, these individuals can navigate higher education with determination and resilience, ultimately transcending the barriers imposed by the STPP.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bell Jr DA (1980) Brown v. Board of Education and the interest-convergence dilemma. Harvard Law Review pp. 518-533.

- Ladson Billings G, Tate WFIV (1995) Toward a critical race theory of education.

- Crenshaw KW (2010) Close encounters of three kinds: On teaching dominance feminism and intersectionality. Tulsa L Rev 46: 151.

- Delgado R, Stefancic J (2017) Critical race theory: An introduction. New York.

- Owusu Bempah A, Gabbidon S (2020) Race, ethnicity, crime, and justice: An realities in adult basic education. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Recommendations for Teacher Education. The Urban Review 49(2): 326-345.

- Valencia RR (1997) The evolution of deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice.

- Dyson ME (2006) Holler if you hear me: Searching for Tupac Shakur. Basic Civitas Education. international dilemma. Routledge 1999(82): 33-48.

- Sheared V (1999) Giving voice: Inclusion of African American students' polyrhythmic Teachers College Record 97(1): 47–68.

- Bryan N (2017) White Teachers’ Role in Sustaining the School-to-Prison Pipeline.

-

Shanice Robinson Blacknell*. Black Urban Storytelling: A Personalized Len on Black Experiences. Iris J of Edu & Res. 2(5): 2024. IJER.MS.ID.000549.

-

Blended learning (hybrid learning); Face-to-face (f2f); Online; Pedagogy; Synchronous learning

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.