Research Article

Research Article

Pre‑Service Teachers’ Engagement with Generative AI in Early Years Education: A Multiple-Case Study from Hong Kong

Anika SAXENA* and Yujie WEI

Department of Early Childhood Education, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Anika SAXENA, Department of Early Childhood Education, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Received Date: December 16, 2025; Published Date:December 18, 2025

Abstract

This study investigates how pre‑service teachers utilise generative artificial intelligence (AI) in early-years lesson planning, how AI is integrated into classroom activities, and the training needs to prepare future educators for the responsible use of AI. A qualitative case study design was used, drawing on in‑depth responses from six pre‑service teachers enrolled in an early childhood education programme. Data were analysed using a structured thematic coding matrix aligned with three research questions, ensuring full thematic saturation and cross‑case comparison. Generative AI supported lesson planning through ideation, resource creation, and differentiation, with participants using tools such as ChatGPT, Canva AI, and DALL·E to generate stories, worksheets, and personalised learning materials. Classroom integration remained cautious and primarily indirect, with AI outputs used as teacher‑mediated resources rather than tools for direct child interaction. Ethical concerns—including bias, age appropriateness, and data privacy—arose among all participants. Pre‑service teachers emphasised the need for practical, hands‑on AI training, clear ethical guidelines, and mentor‑supported practicum experiences. Teacher education programmes should embed AI literacy, ethical frameworks, and experiential learning opportunities to prepare educators to integrate AI safely and developmentally appropriately in early years settings. This study provides one of the first early‑years‑focused analyses of the use of generative AI by pre‑service teachers, offering actionable insights for curriculum design and policy development.

Keywords: Generative AI; Early childhood education; Pre-service teachers; Lesson planning; Teaching materials; Convenience sampling; Case study; AI integration; Teacher education; Thematic analysis

Abbreviations:Generative AI; Early childhood education; Pre-service teachers; Lesson planning; Teaching materials; Convenience sampling; Case study; AI integration; Teacher education; Thematic analysis

Introduction

This study examines how pre-service teachers in early childhood education use generative AI in practice. It focuses on three main areas: how teachers use AI to plan lessons and create materials; how they incorporate AI as a teaching tool in their lesson plans; and how teacher education programs can support future teachers in using AI effectively. The research was motivated by the rapid growth of generative AI in K–12 education and the need for evidence-based guidance in early childhood settings.

Literature Review

GenAI as a Lesson-Planning Assistive Tool: Lesson planning is essential for effective teaching, serving as a guide to keep instruction on track [1]. Yet it requires substantial time and demands both subject-matter knowledge and teaching skills [2]. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), which uses algorithms to generate text, images, and other content, is changing how teachers approach tasks such as lesson preparation. This review examines how large language models (LLMs) in GenAI tools are used for lesson planning and the implications for early childhood education (ECE).

Gen AI offers new options for curriculum planning. Its main advantage is efficiency, as it can quickly create learning goals, activities, and assessments. This helps teachers spend more time on important decisions and with their students [3]. GenAI also fosters creativity by providing teachers with numerous ideas to make lessons more engaging [4]. Because it can create and adapt content, teachers can better match materials to students’ needs, interests, and skill levels, thereby supporting diverse learning approaches.

Collaborative lesson planning, where teachers work together to design lessons and share ideas, plays a key role in professional growth [5,6]. For pre-service teachers, working in groups provides an opportunity to develop lessons collaboratively and discuss teaching concepts with peers [5]. Studies show that collaboration helps pre-service teachers discuss teaching challenges, participate in curriculum decisions, and develop well-structured lesson plans [7,8].

Teachers’ thinking during lesson planning can be studied at both broad and detailed levels [1]. At a broad level, lesson design follows a set of steps: setting goals, selecting content, planning strategies, and determining how to assess students [9]. These steps require teachers to add new ideas and make changes [10] continually. GenAI can support this ongoing process by providing real-time feedback and suggesting content [11].

On a detailed level, Tang and Hew [12] found four types of cognitive engagement: operation (basic understanding), wayfinding (making connections), meaning-making (seeing patterns), and innovation (creating new ideas). In group planning, pre-service teachers work together by talking, solving problems collaboratively, and providing one another with feedback [13]. Digital tools can support these activities [14], but honest reflection requires ongoing effort and repeated improvement. It is still unclear how GenAI influences these thinking processes during group lesson planning.

From Personal Experience to Professional Practice: Educational technology research suggests that teachers’ personal experience with digital tools significantly influences their professional practices and their willingness to integrate technology [15,16]. This implies that familiarity with GenAI in personal or academic contexts may reduce barriers to adoption in professional settings. Early studies support this, showing that greater AI understanding and more frequent AI use correlate with higher future use intentions [17].

However, emerging evidence complicates this narrative. A study of Irish primary school teachers found no significant correlation between personal use of GenAI and perceptions of opportunities, challenges, ethical issues, or professional development needs in lesson planning. Conversely, academic GenAI use was positively correlated with perceived opportunities and professional development needs, but negatively correlated with perceived challenges and ethical concerns [18]. This suggests that while academic use may enhance efficacy, it may also create blind spots regarding limitations and moral implications.

Pre-service Teachers’ Professional Perceptions of GenAI: Understanding pre-service teachers’ willingness to integrate technology requires examining their multifaceted perceptions [19]. This study adopts a framework synthesising four interconnected dimensions: perceived opportunities, perceived challenges, ethical considerations, and perceived professional development needs [20,21].

Perceived opportunities include time savings, efficiency improvements, and stimulation of creativity [3]. Perceived challenges include concerns about the accuracy and reliability of AIgenerated content, the risk of overreliance that undermines teacher autonomy, and potential negative impacts on student learning [22]. Ethical considerations address educational equity, data privacy, and transparency of AI applications [23]. Finally, perceived professional development needs reflect recognition that the practical and ethical use of GenAI requires training [24].

The Hong Kong Early Childhood Education Context: Hong Kong’s unique sociocultural and educational environment critically shapes how pre-service teachers engage with GenAI. The local curriculum framework emphasises play-based learning and holistic child development, prioritising hands-on activities and sensory experiences over direct instruction [25]. This pedagogical orientation poses challenges for GenAI, which primarily operates in digital and textual domains. Text-based activity generation tools may be perceived as less applicable to early childhood teachers than to academically focused educational stages [26].

Additionally, Hong Kong’s bilingual and trilingual (Cantonese, Mandarin, English) policy environment add complexity. Preservice teachers may use GenAI to create bilingual resources, but its proficiency and cultural appropriateness in Chinese may affect reliance and perceived practicality [27]. These contextual factors may moderate relationships between application domains and professional perceptions. For example, experience using GenAI for English academic writing may not translate into designing culturally resonant, play-based Chinese activities, potentially weakening correlations observed in other contexts.

Research Gap and Study Purpose: While GenAI’s integration into lesson planning shows promise, critical gaps remain. First, how pre-service teachers utilise GenAI tools to create teaching materials and resources for the early years remains largely unexplored. Second, the ways in which teachers incorporate GenAI as a teaching tool—rather than merely a planning assistant—in lesson plans require investigation. Third, the implications for teacher training programs that prepare pre-service teachers for effective GenAI integration require clarification.

This study addresses these gaps by examining pre-service early

childhood teachers in Hong Kong and exploring three questions:

RQ 1. How do PSTs use GenAI in lesson planning and material

creation?

RQ2. How is GenAI integrated as a teaching tool?

RQ3. What recommendations can support teacher training

programs in preparing future teachers for effective use of GenAI?

By presenting evidence from Hong Kong, the study aims to inform the global understanding of the integration of GenAI into teaching.

Method

Design

This study uses an exploratory multiple-case approach to examine how PSTs understand and engage with GenAI-facilitated practices. It is a method that allows detailed elaboration of the complexity and characteristics of a small number of cases. This approach provides a rich description of each case and a deeper understanding of the issue [28]. Six participants were chosen for semi-structured interviews. They were recruited and took part in semi-structured interviews conducted in English, which was the shared first language of both the interviewer and the interviewees. Each interview lasted between 50 minutes and one hour. The interview protocols were based on existing literature.

They included three parts: PSTs’ understanding of GenAI, their general and teaching-related GenAI practices, and their GenAI practices in relation to identity. Before the interviews, participants were asked to share screenshots of their GenAI practices. These were discussed during the interviews. This helped the interviewer explore the conditions and contexts that shaped their GenAI practices, particularly with respect to identity and investment.

Participants and context of the study

The sample consisted of six ECE pre-service teachers (n=6). Inclusion criteria required participants to demonstrate willingness to use or reflect on generative AI tools and to provide consent to share anonymised lesson artefacts and to participate in interviews. Convenience sampling was employed based on accessibility within a single cohort. The participants had similar educational backgrounds. There were two male and four female PSTs. Their ages ranged from 20 to 23 years. All participants signed consent forms and were assigned pseudonyms. Although some had experience with AI tools in their personal lives, none had previously used AI to generate lesson plans for young learners.

Data collection and analysis

This research employed an interpretive approach better to understand PSTs’ views and experiences with GenAI. A qualitative research design was used to answer the three research questions. Individual semi-structured interviews (Appendix A) enabled deeper exploration of the topic. The study used convenience sampling. The first author invited instructors from a technology-based course at a university in Hong Kong to participate..

The following definition was used: ‘Generative artificial

intelligence (AI) describes algorithms (such as ChatGPT) that can

be used to create new content, including audio, code, images, text,

simulations and videos’ [29]. The interview guide included the

following questions:

The data sources comprised: (a) AI-assisted lesson plans and

teaching materials, (b) a semi-structured interview protocol, (c)

reflective memos, and (d) optional planning logs or screenshots of

AI prompts and outputs.

Procedures

The procedures consisted of four phases: (1) recruiting participants and obtaining consent, (2) collecting lesson artefacts and planning logs over a period of two to four weeks; (3) conducting interviews lasting 30 to 45 minutes; and (4) member-checking of thematic summaries.

The interviews were conducted in English and lasted 30- 45 minutes each. Each interview was audio-recorded and then analysed using a manual, step-by-step thematic approach. This analysis method [30] provided a thorough, detailed understanding of the data. The recordings were first transcribed into written form. These transcripts were then shared with participants for an initial member check. After that, the three authors carefully reviewed and re-examined the transcripts to become familiar with the data.

Next, each author independently coded the transcripts and created initial codes. They shared, discussed, and refined these codes together using Google Docs. They agreed on the main themes and sub-themes. A code-and-recode strategy was used to improve the consistency and reliability of the findings [31]. Both authors reviewed the data again and re-coded it two weeks after the first round of coding. The near-identical results confirmed the integrity of the findings. A second member check was conducted to enhance the reliability of the data further. Participants received a summary of the study’s findings, which included the identified themes and sample quotations. None of the language instructors suggested or requested any changes during either of the two member checks.

Data analysis employed an inductive-deductive thematic approach, using a coding framework aligned with the research questions, including usage types, levels of pedagogical integration, and perceived benefits and challenges. Cross-case matrices were used to support pattern matching. Trustworthiness was established through triangulation, maintaining an audit trail, member checking, and peer debriefing.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations included obtaining informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, securely storing artefacts, anonymising AI prompts and outputs, disclosing the tool’s limitations, and adhering to school policies on children’s data.

Data Analysis, Findings and Discussion”

Participants regularly used generative AI for lesson planning, classroom activities, and preparing for teaching in early years education. Each of the six participants contributed to all sub-themes, indicating that the analysis was thorough and well-organised. We have grouped the results into four main themes that emerged from the analysis. Based on the study of the six participants’ data, a comprehensive thematic mapping table was developed to organise the coding structure across three main research questions (RQ1- RQ3) and fourteen sub-themes (Appendix B: Table 1-Data Coding for Six Participants in a Case Study on Generative AI Use in Early Years Education)

Core Mapping Structure

The data coding table uses a thematic framework to organise participant responses around three main research questions. For RQ1, which looks at how generative AI is used in lesson planning, responses fall into three sub-themes: ideation and brainstorming, resource and material creation, and differentiation and personalisation. These sub-themes illustrate the different ways in which preservice teachers (PSTs) used AI tools to support planning and content adaptation. RQ2, which focuses on the ethical considerations of AI in early education, is divided into three sub-themes: accuracy and age appropriateness, bias and representation, and ethical concerns. This section highlights participants’ reflections and concerns regarding the suitability of AI for early years settings and its potential effects. RQ3 on teacher training needs for AI integration comprises four sub-themes: curriculum integration, ethical guidelines, practical training, and policy recommendations. This last category captures participants’ suggestions for building AI literacy and preparing teachers through education programs.

Key Findings from Mapping

The mapping showed that all six participants responded to all six sub-themes across the three research questions. This comprehensive coverage highlights the strength of the coding framework and its sustained engagement with the main issues. All participants, no matter their views or experience with AI, raised ethical concerns. This indicates a shared understanding of the risks and responsibilities associated with the use of AI in early childhood settings. Participants also emphasised the importance of practical, hands-on training over purely abstract or theoretical instruction. They recommended simulations, practicum experience, and mentor-led approaches as the most effective means to help educators use AI meaningfully and responsibly.

Data Analysis, Findings and Discussion Use of Generative AI in Lesson Planning

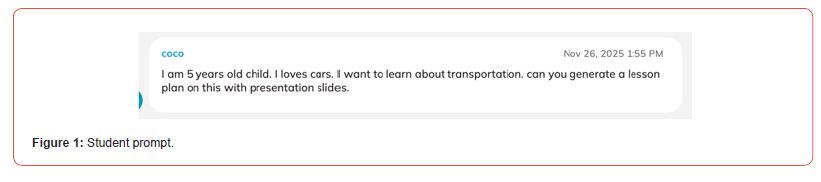

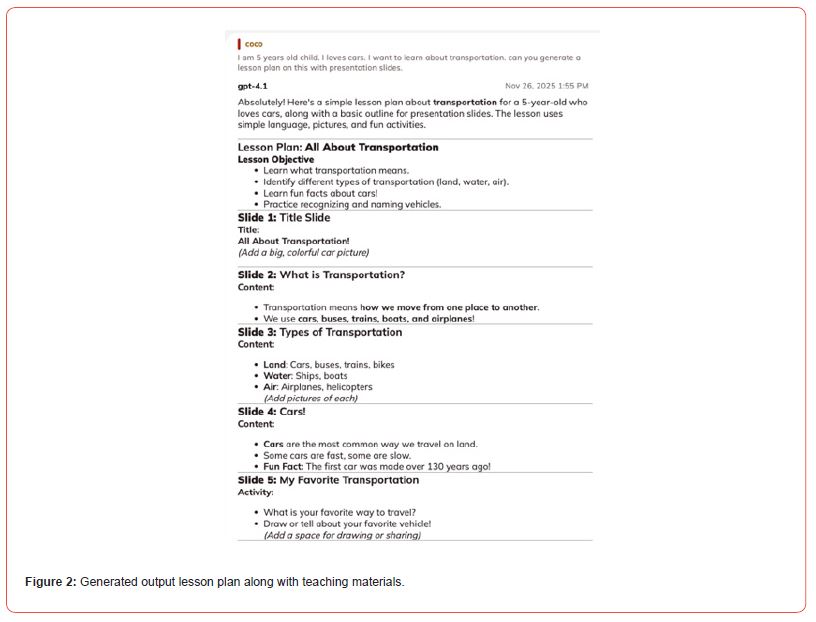

Generative AI facilitated brainstorming, material creation, and lesson adaptation. Participants used ChatGPT to generate story prompts, rhyming songs, science experiments, and math games, demonstrating its creative use in early childhood education [32,33]. Canva AI, Yochatgpt and DALL·E made it easier to produce worksheets, flashcards, and illustrations, but teachers still needed to check the materials [34]. Teachers also used AI to adapt stories to different language levels and to tailor science activities to students with varying abilities, which aligns with research on AI-supported personalisation [35]. Participants stressed the need to review AIgenerated materials for accuracy, cultural relevance, and suitability for young children. Figure 1 shows the student prompt, and Figure 2 shows the generated lesson plan along with teaching materials.

Integration of AI in Classroom Activities

Teachers mostly used AI indirectly in classroom activities, such as making props, handouts, flashcards, and visual prompts. This careful approach aligns with trends in K–12 education, where teachers guide the use of AI to maintain control over instruction and ensure that content is appropriate for students’ age [36]. Participants were hesitant to allow students to use AI directly because they were concerned about students’ readiness, potential bias, and unpredictable results. These findings align with recommendations for teachers to guide the use of AI in early years education [37].

The analysis revealed that pre‑service teachers used generative AI not only to streamline lesson planning but also to personalise learning experiences based on children’s individual interests. Participants described how AI tools such as ChatGPT could quickly adapt a standard activity into a themed version aligned with a child’s preferences—for example, transforming a counting exercise into a “Hello Kitty counting adventure” or redesigning a science exploration around dinosaurs. This capacity for rapid customisation enabled teachers to create highly engaging and relatable learning materials with minimal preparation time. Such practices align with emerging research showing that AI can support interest‑driven learning by generating contextually relevant narratives and examples that resonate with young children’s motivations [32,35]. Participants emphasised that these personalised adaptations made lessons more enjoyable and meaningful for young learners, while also reducing the workload associated with manual differentiation.

The ability of generative AI to personalise lesson content based on children’s interests has critical pedagogical implications. Interest‑driven learning is widely recognised as a catalyst for deeper engagement, intrinsic motivation, and sustained attention in early childhood education, and AI appears to offer a practical mechanism for embedding such personalisation into everyday teaching [32]. The findings suggest that AI can function as a flexible pedagogical assistant, enabling teachers to tailor activities quickly without compromising developmental appropriateness. However, consistent with the existing literature, participants also exercised caution, noting that AI‑generated content still requires teacher oversight to ensure cultural relevance, accuracy, and alignment with early-years learning goals [28,33]. While AI offers unprecedented efficiency in adapting lessons to children’s interests, its responsible use depends on teachers’ professional judgement and their ability to evaluate AI outputs critically. This underscores the need for teacher education programmes to incorporate training on both the creative and ethical dimensions of AI‑supported personalisation.

Recommendations for Teacher Education Programs

Participants suggested that teacher education programs should provide more practical, hands-on training in AI. They recommended adding modules, workshops, and AI-related assignments to different subjects. These ideas align with UNESCO’s AI Competency Framework, which emphasises learning by doing and ethical understanding [38]. Participants also sought clear rules, privacy protections, and mechanisms to verify AI outputs, consistent with international standards for trustworthy AI [39,40]. Practice with mentors and simulation exercises is considered necessary for building confidence and encouraging responsible AI use in classrooms, as RAND also supports [41].

Cross‑Cutting Insights

Ethical issues, including bias, age appropriateness, and privacy, arose across all themes, indicating that teacher training should address ethical considerations. The findings highlight the need to balance the benefits of AI with careful use in early childhood education. Teachers used AI for planning, but its use in the classroom was limited and closely watched. In short, generative AI supports lesson planning and resource development, but effective use requires rigorous training, ethical awareness, and professional judgment.

Conclusion, Implications, and Limitations

This study explored how pre-service teachers used generative AI for lesson planning, classroom activities, and preparation in early years education. The findings indicate that generative AI is already a helpful teaching tool, particularly for generating ideas, creating resources, and supporting diverse learning needs. Participants used AI to generate story prompts, science activities, math games, and visual materials, which suggests that AI can help teachers be more creative and efficient when used thoughtfully [32,42,43]. They also relied on their professional judgement to edit AI outputs so they were appropriate for children’s development, culturally relevant, and accurate. This aligns with recent research highlighting the importance of teachers guiding AI-supported planning [35,44].

Despite these benefits, teachers were cautious and mainly used AI in indirect ways in the classroom. They used AI-generated materials as props or handouts. Still, according to Bergdahl & Sjöberg [45], the data did not permit children to interact directly with the AI because of concerns about children’s readiness, as well as potential bias and unpredictability. All participants raised ethical concerns, particularly regarding data privacy, bias, and the suitability of AI for young children, which supports global calls for trustworthy, human-centred AI in education [38-40].

These findings have important implications for teacher education. There is a clear need for practical, hands-on AI training that goes beyond theory. Participants preferred workshops, practicum projects, and mentorship, which support Kolb’s view that learning by doing is essential for AI readiness [46]. Teacher preparation should also include robust ethical training, clear policies, data privacy regulations, and mechanisms for evaluating the use of AI. Including AI across all subject-methods courses, rather than teaching it separately, will help pre-service teachers use AI tools in real-world teaching contexts.

This study has some limitations. First, only six pre-service teachers from a single program participated, so the results may not be generalised to other programs or groups. While the main themes were addressed, the views expressed may not reflect broader trends. Second, because the study relied on selfreported data, there may be bias if participants provided socially desirable responses about AI or differed in their experience with AI. Observing classrooms or reviewing actual teaching materials could provide a deeper understanding. Third, because AI is evolving rapidly, these experiences are merely a snapshot in time. Future AI tools may present both opportunities and challenges. Finally, because the study focused on early years education, which introduces additional developmental and ethical concerns, the findings may not generalise to primary or secondary schools, where students may interact more with AI. In summary, generative AI has strong potential to support early years educators, but effective use requires careful planning, ethical awareness, and high-quality teacher training. As AI advances, teacher education programs must keep pace so that new teachers are prepared to use, assess, and responsibly incorporate AI tools into early childhood teaching.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating pre-service and mentor teachers for their time and openness.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu SQ, Zou DD (2014) Preliminary study on collaborative lesson planning based on a cloud platform. Applied Mechanics and Materials 548-549: 1433-1437.

- Alanazi MH (2019) A Study of the Pre-Service Trainee Teachers Problems in Designing Lesson Plans. Arab World English Journal 10(1): 166-182.

- Van den Berg G, Du Plessis E (2023) ChatGPT and Generative AI: Possibilities for Its Contribution to Lesson Planning, Critical Thinking and Openness in Teacher Education. Education Sciences 13(10): 998.

- Kılıçkaya F, Kic-Drgas J (2025) Pre-service language teachers’ experiences and perceptions of integrating generative AI in practicum-based lesson study. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12(1).

- Guo C, Chen X, Chen J (2025) Enhancing prospective teachers’ professional development through shared collaborative lesson planning. Behavioural Sciences 15(6): 753.

- Backfisch I, Franke U, Ohla K, Scholtz N, Lachner A (2023) Collaborative design practices in pre-service teacher education for technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): Group composition matters. Unterrichtswissenschaft 51: 579–604.

- Pepin B, Kohanová I, Lada M (2025) Developing pre-service teachers’ capacity for lesson planning with the support of curriculum resources. ZDM — Mathematics Education, 57: 1003–1017.

- Gutierez SB (2020) Collaborative lesson planning as a positive ‘dissonance’ to the teachers’ individual planning practices: Characterizing the features through reflections-on-action. Teacher Development.

- Krepf M, König J (2022) Structuring the lesson: an empirical investigation of pre-service teacher decision-making during the planning of a demonstration lesson. Journal of Education for Teaching International Research and Pedagogy 49(5): 911–926.

- Fujii T (2016) Designing and adapting tasks in lesson planning: a critical process of Lesson Study. ZDM 48(4): 411–423.

- Bai S, Lo CK, Yang C (2024) Enhancing instructional design learning: a comparative study of scaffolding by a 5E instructional model-informed artificial intelligence chatbot and a human teacher. Interactive Learning Environments 33(3): 2738–2757.

- Tang Y, Hew KF (2022) Effects of using mobile instant messaging on student behavioural, emotional, and cognitive engagement: a quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 19(1): 3.

- Yan J, Goh HH (2023) Exploring the cognitive processes in teacher candidates’ collaborative task-based lesson planning. Teaching and Teacher Education 136: 104365.

- Hrastinski S (2021) Digital tools to support teacher professional development in lesson studies: a systematic literature review. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies 10(2): 138–149.

- Otterbreit-Leftwich AT, Brush TA, Strycker J (2012) Preparation versus Practice: How Do Teacher Education Programs and Practicing Teachers Align in Their Use of Technology to Support Teaching and Learning?. Computers & Education 59(2): 399-411.

- Ertmer PA (1999) Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educational Technology Research and Development 47(4): 47–61.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD (2003) User acceptance of information Technology: toward a unified view. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Hsu Hsiao-Ping, et al. (2024) Preliminary Study on pre-service teachers’ applications and perceptions of generative artificial intelligence for lesson planning. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 32(3): 409-437.

- Farjon D, Smits A, Voogt J (2019) Technology integration among pre-service teachers: explained by attitudes and beliefs, competencies, access, and experience. Computers & Education 130: 81-93.

- Chan CKY, Zhou W (2023) An expectancy value theory (EVT) based instrument for measuring student perceptions of generative AI. Smart Learning Environments 10(1): 64.

- Zhang C, Schießl J, Plößl L, Hofmann F, Gläser-Zikuda M (2023) Acceptance of artificial intelligence among pre-service teachers: a multigroup analysis. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 20(1): 49.

- Moorhouse BL, Kohnke L (2024) The effects of generative AI on initial language teacher education: The perceptions of teacher educators. System 122: 103290.

- Whalen J, Mouza C (2023) ChatGPT: Challenges, opportunities, and implications for teacher education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 23(1): 1-23.

- Gatlin M (2023) Assessing Pre-service Teachers’ Attitudes and Perceptions of Using Artificial Intelligence in the Classroom. Texas Educator Preparation 7(2): 1-8.

- Hong Kong Curriculum Development Council (2017) Kindergarten education curriculum guide. The Education Bureau, HKSAR.

- Keung CPC, Cheung ACK (2019) Towards Holistic Supporting of Play-Based Learning Implementation in Kindergartens: A Mixed Method Study. Early Childhood Education Journal 47(5): 627–640.

- Li DCS (2022) Trilingual and biliterate language education policy in Hong Kong: past, present and future. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education 7(1).

- Duff PA (2014) Case study research on language learning and use. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 34: 233–255.

- McKinsey & Company. What Is Generative AI? McKinsey & Company.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J (2014) Qualitative data analysis a methods sourcebook.

- Uğraş H, Uğraş M, Papadakis S, Kalogiannakis M (2024) Innovative Early Childhood STEM Education with ChatGPT: Teacher Perspectives. Technology Knowledge and Learning 30(2): 809–831.

- Zeeshan K, Hämäläinen T, Neittaanmäki P (2024) ChatGPT for STEM Education: A Working Framework. International Journal of Learning and Teaching pp. 544–548.

- Workman J (2023) The power of Canva AI: A game changer in content creation. Artificial Intelligence in Education Conference: Shaping Future Classrooms (pressbook chapter).

- Jauhiainen JS, Garagorry Guerra A (2024) Generative AI and education: Dynamic personalisation of pupils’ school learning material with ChatGPT. Frontiers in Education 9: 1288723.

- Diliberti MK, Schwartz HL, Doan S, Shapiro A, Rainey LR, et al. (2024) Using artificial intelligence tools in K–12 classrooms (Research report). RAND Corporation.

- Mst JVC (2025) The influence of privacy, bias, and surveillance concerns on teachers’ willingness to use artificial intelligence in education. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science IX(IIIS): 3192–3208.

- UNESCO (2024) AI competency framework for teachers. UNESCO.

- European Commission High‑Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (2019) Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. European Commission.

- Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) (2019) OECD principles on artificial intelligence. OECD.

- Goff WM (2025) Immersive learning in teacher Education: simulated environments, tools, and practices: Simulated Environments, Tools, and Practices. IGI Global.

- ElSayary A, Kuhail MA, Hojeij Z (2025) Examining the role of prompt engineering in utilizing generative AI tools for lesson planning: insights from teachers’ experiences and perceptions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2025(1).

- Nikolopoulou K (2025) Child-centered integration of generative AI in early learning: balancing promises and challenges. AI Brain Child 1(21).

- Jauhiainen JS, Guerra AG (2024) Generative AI and education: dynamic personalization of pupils’ school learning material with ChatGPT. Frontiers in Education, 9.

- Bergdahl N, Sjöberg J (2025) Transformation, support needs and AI, in K-12 education. Educ Inf Technol.

- Kolb DA (1983) Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development.

-

Anika SAXENA* and Yujie WEI. Pre‑Service Teachers’ Engagement with Generative AI in Early Years Education: A Multiple-Case Study from Hong Kong. Iris J of Edu & Res. 6(1): 2025. IJER.MS.ID.000625.

-

Generative AI, Early childhood education, Pre-service teachers, Lesson planning, Teaching materials, Convenience sampling, Case study, AI integration, Teacher education, Thematic analysis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Language Representation in the Brain

- What are the Cognitive and Neural Consequence of Bilingualism?

- Developmental Changes across Lifespan in Bilingualism

- Neuroimaging Tools to Study Bilingualism

- Language Experience and Neuroplasticity

- Conclusion and Future Direction

- Acknowledgment

- Conflict of Interest

- References