Review Article

Review Article

Mapping of Dietary Risks in Indigenous People: A Scoping Review

Shruti Sharma and Ravi Naidu*

Global Centre for Environmental Risk Assessment and Remediation (GCER), The University of Newcastle, Australia

Ravi Naidu, Global Centre for Environmental Risk Assessment and Remediation (GCER), The University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia

Received Date:March 10, 2022; Published Date:April 12, 2022

Abstract

Indigenous people across the globe suffer major health disparities compared to non-indigenous people. Historic acculturation and discrimination in almost every aspect of living, is the major determinant. On the same note, change of dietary habits in this population, from traditional to modern, has been a much-discussed topic in literature. The information on current dietary patterns and related nutritional disorders are thus crucial and hence forms the scope of present review. The key question that we intend to explore through this literature review is the trend of dietary habits in indigenous people from the countries where such information is available. Online literature databases, government repositories & reports were searched for collection of papers published from 2009 to 2019. Findings indicate – Almost 55% of retrieved literature from mentioned sources were from 5 countries -Australia, Canada, United States, New Zealand and India. Result shows that macronutrients and micronutrient deficiencies are major concern with respect to the prevailing nutritional disorders in the indigenous people However, more comparative research is needed to proclaim the effect of a dietary aspect as a causation of prevailing nutrition related disease. We recommend that a nutrient balanced system is the need of hour and that there must be unique food environment planning strategies in place to serve vulnerable populations.

Keyword:Dietary risks; Review literature; Indigenous nutrition; Indigenous diet; Indigenous health

Introduction

Around 370 million indigenous people worldwide are the most marginalized people; members of the group die relatively younger than their non-indigenous compatriots [1-4]. During 2009-2013, 81% of indigenous Australians died before the age of 75 years, compared with 34% of the non-indigenous Australian [5]. Indigenous peoples’ early deaths in most of the nations across the globe result in significant life expectancy gaps (LEG) compared to the rest of the population, including some of the wealthiest countries of the world [6-9]. There was a time when Indigenous people lived in their healthiest state [10]. Many studies relate wellbeing to their traditional way of living – largely described by consumption of traditional food and intense physical activity due to leading hunter-gatherer life style [11-13]. Traditional foods had special value among indigenous communities. It was a way to keep their relationships with their environment, cultures and traditions. The concept of being able to consume traditional food was related to their overall health [14]. However, the modern lifestyle does not support their old way of living any more. The change from a traditional food based diet energy dense processed food witnessed introduction of alien diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and cancers in varied populations across the globe [15-17]. Therefore, in the present review, we focus to study literature surrounding indigenous health and their dietary habits in modern age to suggest future solutions to indigenous health.

Method

We conducted scoping review based on the available literature

to assess breadth of the topic, identify any gaps and summarise our

findings [18]. The idea was to provide an overview of the work performed

in this area, and its extent [19]. The stages for conducting

scoping review was as follows:

I. Identification of the research question

II. Identification of relevant studies

III. Study selection

IV. Charting the data

V. Summarizing and reporting of data

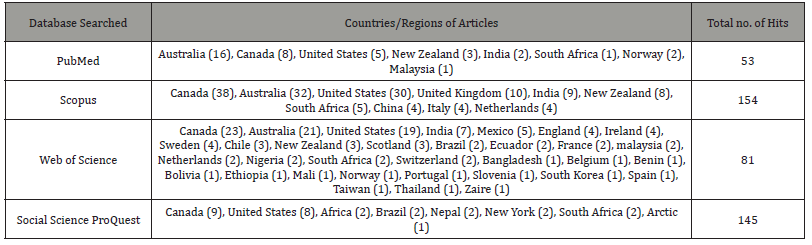

Online databases - PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Social Science ProQuest were searched for indigenous people’s dietary intake information (Table 1). National repositories and reports were searched by accessing country national websites. Manual searching was also conducted on Google Scholar to avoid missing of important relevant articles. The search strategy for electronic databases was developed with the requisite skill in devising appropriate search strategies. The first author holds experience in searching databases and is equipped with literature search experience. Two search strategies were developed in order to fetch the relevant articles for conducting scoping review of the concept. 1. Nutritional health issues related articles. 2. Dietary intake related articles. Keyword used along with Boolean operators-indigenous, tribal, diet, dietary intake, food, food intake, health problem, health issue, health, disease, aboriginal, aboriginal and torres strait islander, disease, diabetes, overweight, obesity, hypertension, undernutrition, malnutrition, traditional food, over nutrition, energy intake, nutritional disorder. Inclusion and Exclusion criteria: Those articles/documents which mentioned about the food intake and nutritional disorders in indigenous people were retained. The literature were selected for last 10 years and anything prior to that was excluded. Any article other than diet and existing health condition information was excluded from further analysis. Any non-English documents and duplicates were also excluded during refining process. Most importantly, the articles that showed a comparison between indigenous and non-indigenous populations in the same region were retained.

Table 1:

The Review

Amongst, all the combinations, INDIGENOUS AND “DIETARY INTAKE” keyword combination yielded the best relevant results for information pertaining to diet in indigenous population. Hence, the number of results were used to analyze the number of articles from source countries. In article title Scopus-7documents were retrieved but after applying a filter for last 10 years 5 articles appeared in the search results. After removal of duplicates and non-English literature, 2 articles were retained for analysis and they were both from Australia. The articles discusses about disparities in dietary intake and anthropometric measurements. In Abstract when searched, 84 documents appeared however for the last 10 years 47 articles were extracted for analysis. Out of 47 records in Abstract filter, one article from Norway reported no ethnic differences in the dietary intakes of indigenous and non-indigenous populations. The article when searched in PubMed had 53 records for the last 10 years. Out of these articles, 52 had these keywords in the abstract section. Two articles were from India-1. Oraon tribal women, Jharkhand, and 2. Santhal community Jharkhand. Both estimated indigenous food consumption to dietary consumption in tribal women. Two articles were retained from Canada 1. Study among Cree people in norther Quebec, and 2. First nations in 4 Canadian provinces. Two articles, both from Australia, were duplicated as of Scopus results. Similar Norway study of no ethnic disparity in dietary intake was obtained during PubMed search. In Web of Science search, 40 articles belonged to the field of “Nutritional Dietetics”, 25 in “Public Environmental and Occupational Health”, 8 in “Environmental Sciences”, 5 in “Food Science and Technology” and 4 in “Anthropology”. When searched in “Nutritional dietetics”, 11 articles were already been retrieved during Scopus and PubMed searches. 7 new articles were included from Web of Science search. Social Science ProQuest database search yielded Cultural Anthropology (34), Physical Anthropology (29), Public health (26), Nutrition (25), Studies (22), Food (18), Diet (16), Food Supply (14), and Humans (11) related articles. One article was replicated in the search result. 4 new articles were included from social science database ProQuest search results. Maximum number of articles from above databases were from Canada (78), Australia (69), United States (62), New Zealand (14) and India (18). 241 articles came from these 5 countries out of 433 total articles retrieved. The diseases related to nutritional disorders were mapped in the above mentioned countries. Search keywords included- diabetes, obesity, hypertension, high blood pressure, malnutrition, and excess nutrition. 40 articles were included which discussed the prevalence of nutrition related health problems in indigenous populations [20-87] (Table 2).

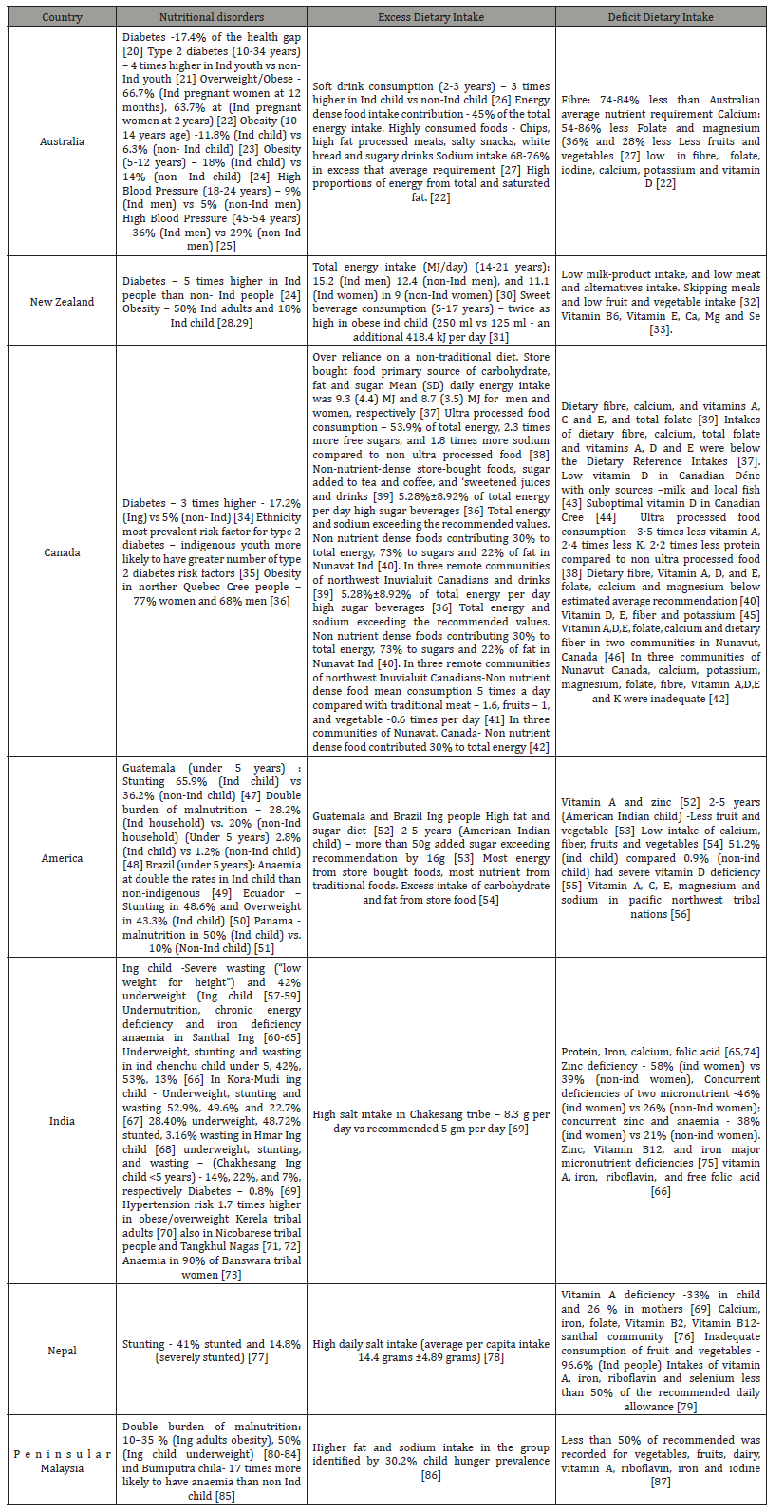

Table 2:

Studies Reporting Dietary Intakes in Association with Metabolic Risk Factors

Only one study was found which contained both dietary intake and anthropometric measurements from Australia [22]. Another, study in northern Australia reported overweight/obese Ind youth were 1.89 times more likely to eat dugong (a traditional food –sea mammal) [88]. Increase in market food consumption and BMI was reported in a study from Canadian indigenous people [89]. In the northern Quebec Cree population, where obesity rates were significantly high, individuals drank high sugar containing beverage everyday contributing 5.28%±8.98% to total energy intake [36]. Ultra-processed food was highly related with metabolic syndrome in Cree of northern Québec, Canada [90]. In three Cree communities of northern Quebec, reported as 67.6% overweight prevalent region, 96.8% people consumed 39% of total energy from high fat foods, and 92.8% consumed 12.8% of total energy from high sugar foods [91]. In three communities of Nunavat Canada, where obesity prevalence was ˃ 70%, non-nutrient dense foods were primary source of fat, carbohydrates and sugar [42]. In New Zealand, Obese Ind child’s medium sweet beverage consumption is reported in comparison with nonindigenous child [31]. Overweight vs normal weight children reported significantly more sweetened beverage intake (8.0±0.10 vs 5.28±0.08 oz/day, P<0.01) [53]. In India, maternal malnutrition post-natal high salt intake is thought to be associated with hypertension [92]. This is based on the hypothesis that similar results have been observed in animals, wherein animal the deficiency of macro and micronutrients led to nephron endowment which made them susceptible to high salt sensitive and both of these factors together predispose to hypertension. This basis has been applied to suggest similar effects on population affected by malnutrition endemic. Especially countries like India where poor rural and vulnerable population face significant burden of malnutrition. In Mandla district of India, in 3090 adult tribals, hypertension was strongly associated with increase in BMI especially those BMI who had greater than 25. The prevalence of hypertension was significantly greater among those whose salt intake was more than 10 g per day [93]..

Traditional Food (TF) Intake-Benefits and Negatives

when TF was consumed, there was a higher intake of protein, iron, vitamins A, C, D minerals such as magnesium and a lower intake of carbohydrates, saturated fat, and fiber and a lower sodium: potassium ratio (P≤0.05) [36,94]. Traditional food contributed 56% of protein and 49% of iron in three communities of Nunavat, Canada [40] and 40% and 42% respectively in other two commu nities for protein and iron respectively [46]. In santhal Community women in Jharkhand, India – those women who consumed indigenous food in past two days of survey had higher intake levels of calcium and iron levels [65]. In three communities of Nunavat, Canada, traditional food for 21% energy and ˃ 50% intakes of protein and iron [42]. Consumption of native marine foods has decreased significantly in Alaskan native women since 1960 and is highly associated with serum vitamin levels [95]. Among Inuits, lead exposure was associated as a potential cause of Unexplained Anaemia, where the participants were not iron deficit. The unexplained anaemia was highest in traditional regions [96]. Lead intake - 1.7 times higher in Ind vs non-Ind [97] and Methylmercury - 1.6 times higher in Ind vs non-Ind [98].

Socioeconomic Condition and Metabolic Risk Factors

Low education and income people groups including American Indians/Alaskan Natives are vulnerable to added sugar [99]. In Thangkhul in Manipur, North east, overweight (25.1%) in tribal women was associated with higher socioeconomic status especially occupation and income – when compared to their non-tribal counterparts [100]. A study in Peninsular Malaysia, food insecure group is significantly associated with higher BMI with multivariate analysis of covariance and also in a group where child hunger was most prevalent high fat and sodium intake scores were reported than food secure groups [86]. In contrast, Income and wealth were significantly associated with fatness measures. They also reported income and adiposity increase during 1962-2006 in Xavante people in Brazilion Amazon [101].

Summary

There have been 16 studies reporting differences in nutrition related health problems of indigenous people compared to non-indigenous people in respect of type 2 diabetes, obesity, blood pressure, stunting, malnutrition, double burden of malnutrition, anaemia. 3 studies discussed nutritional discrepancies in terms of excess consumption of an unhealthy diet pattern- sweet beverage consumption (2) and total energy intake (1). Saturated fat and sodium leading contributors in the etiologies of nutrition related health issues [102-104] were not compared in the two populations. 2 articles compared indigenous person’s micronutrient deficiency in comparison with non-indigenous individual. Other studies report these deficiencies in comparison with recommended nutritional values. Total 18 studies reported unhealthy excess intake of at least one of the items - saturated fat, sugary food, salt or sodium, and non-nutrient dense/store bought/highly processed food. 8 studies – 6 from Canada, 1 from Australia and 1 from America discussed about consumption of store bought or highly processed or non-nutrient dense food. 6 studies discussed high sweet beverage consumption or added sugar exceeding the recommended limit or sugar contribution from high processed foods. 5 articles discussed about high fat consumption. 5 articles discussed excess salt or sodium intake out of which three were from India, Nepal and Malaysia. We did not find excess intake of any other macronutrient in studies from India and Nepal. One study from peninsular Malaysia reported excess intake of both fat and salt in child hunger group and higher BMI’s association in food insecure group. Total 25 articles reported vitamin and mineral deficiencies in these countries, with some concurrent deficiency articles in India. Deficiencies are common in all the countries included in the present study - Australia (2), New Zealand (2), Canada (9), America (5), India (6), Nepal (1), and Peninsular Malaysia (1). Canada and India has maximum number of articles published. The vitamins found deficient in these population were Vitamin A, C, D, E, K, B6, B12, folate, riboflavin. Minerals such as iron, calcium, magnesium, potassium, zinc. Less than adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables & fibre is reported in 3 articles. Protein is the only macronutrient whose deficiency is reported in an article from Indian subcontinent. Two studies reported deficiencies in comparison with their non-indigenous counterparts. Three studies report vitamin A & D deficiency and inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption in indigenous child, two from Canada and one from India. 1 study assessed dietary intake and anthropometric measurement directly. 9 studies find indirect association of exploring high intake consumption patterns in obesity prevalent regions. Two studies in India aim to relate hypertension with salt intake by an indirect association. 7 articles discussed the potential benefits of traditional food consumption in communities today. It increased intake of vitamins and minerals including protein and decreased intake of carbohydrate, fat and sodium. One study from Canada reports less intake while on ultra- processed food compared to being on non-processed diet in terms of Vitamin A, K and protein intake. 3 studies discussed low income, education and food insecure group as vulnerable for high fat, sugar and sodium intake and therefore increase in BMI. In India, 1 study related increased overweight in tribal women with an increase in income.

Strengths and Limitations

The attempt to study dietary patterns across indigenous populations and identify any trend is the major strength of this review. Indigenous culture is diverse and unique however, the health gap is common in most of the countries of their presence. Hence, with the help of present study, we intended to collect as much information available to look for patterns that could help stakeholders take informed decisions. Use of online databases, systematic search of relevant articles, manual searching to identify any missing article during database search, refining and extraction of appropriate data and working of two authors individually to screen relevant articles were crucial aspects during the study. The limitation exist, in the exclusion of articles in indigenous languages that could have added to the trends discovered in the present study. Additionally, indigenous people are widely spread and lack of data pertaining to diet from all those countries and indigenous communities within the same country is a major limitation.

Conclusion

Nutrition related health disorders are prevalent in indigenous people and their contribution to causing health gap is obvious in light of the comparisons presented with respect to non-indigenous people in the same region. Non-nutritive dense food appears to be a major contributor to the imbalanced health factors. However, the strong evidential support comparing dietary and metabolic risk factor in the indigenous and non-indigenous population remain scarce. Sugar, saturated fat and sodium are major contributors of imbalanced energy intake in indigenous people, the primary source being store bought non nutrient dense foods in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and America. Excess intakes are hardly reported in studies from India and Nepal except salt but they are nowhere less in terms of reporting deficiencies. Based on available articles, we can say that micronutrient deficiencies are profound in indigenous people across regions whereas excess consumption is significant in affluent nations. Since low income, education and food unsecure groups might show vulnerability towards developing unhealthy consumption behavior, the increase in the socioeconomic status of indigenous people in developing economies should be targeted for creating healthy food environment models where excess consumption can be avoided and deficiencies could be balanced with nutrient dense diet system. More studies are needed to validate the excess consumption behavior and micronutrient deficiencies guided by highly processed foods in indigenous population. However, the research base is sound to support traditional food’s association with increased intakes of vitamins and minerals. In a population, where traditional foods have diminished and there in inadequate fruits and vegetable intake as the source of rich vitamins and minerals, appropriate strategies are needed to develop a system for providing balanced nutrients.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Drs Prashant Srivastava, Dane Lamb, Ayanka Wijayawardena and Morrow Dong for their support during research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of Interest to declare.

References

- (2006) The Indigenous World. International Working Group on Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), ECOSOC Consultative Status. p. 10.

- UN (2007) Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Voices. Fact sheet. United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

- WHO (2007) Health of indigenous peoples. In: Media center Fact sheet N° The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- IWGIA (2018) The indigenous world, international work group for indigenous affairs, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- AIHW (2015) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework 2014: data tables. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- UN (2009) State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development, Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, New York.

- UN (2014) The Health of Indigenous Peoples. Inter-Agency Support Group on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues. New York.

- Silburn K, Reich H, Anderson I (2016) A Global Snapshot of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples’ Health. Melbourne: The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Collaboration.

- (2017) The Lancet. Big challenges ahead for Indigenous health in Australia 389(10071): 764.

- Eaton SB, Konner M, Shostak M (1988) Stone agers in the fast lane: chronic degenerative diseases in evolutionary perspective. Am J Med 84(4): 739-749.

- Leonard WR, Robertson ML (1997) Comparative primate energetics and hominid evolution. Am J Phys Anthropol 102(2): 265-281.

- Murray SS, Schoeninger MJ, Bunn HT, Pickering TR, Marlett JA (2001) Nutritional composition of some wild plant foods and honey used by Hadza foragers of Tanzania. J Food Compos Anal 14(1): 3-13.

- Pontzer H, Wood BM, Raichlen DA (2018) Hunter‐gatherers as models in public health Obes Rev 19(Suppl 1): 24-35.

- UN (2010) Indigenous peoples: Poverty and Well-being. State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Press Release Produced by the United Nations Department of Public Information. New York.

- Barnard ND, Nicholson A, Howard JL (1995) The medical costs attributable to meat consumption. Prev Med 24(6): 646-655.

- Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, et al. (2000) Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr 72(4): 912-921.

- Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M (2005) The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ 83(2): 100-108.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5(1): 1-9.

- Arksey H, O Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(19): e32.

- AIHW (2017) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework: supplementary online tables. Cat. no. WEB 170.

- AIHW (2014) Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014. Type 2 diabetes in Australia’s children and young people: a working paper. Diabetes Series no. 21. Cat. No. CVD 64.

- Ashman AM, Collins CE, Weatherall LJ, Keogh L, Brown LJ, et al. (2016) Dietary intakes and anthropometric measures of Indigenous Australian women and their infants in the Gomeroi gaaynggal cohort. J Dev Orig Health Dis 7(5): 481-497.

- ABS (2013) Updated Results, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey. Catalogue 4727.0.55.006. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Ministry of Health (2015) Māori health data and stats. Annual update of key results 2014/15: New Zealand health survey. Wellington, New Zealand.

- (2014) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2014 Report. High blood pressure. Figure 1.07-3 measured high blood pressure, by Indigenous status, age, and sex.

- ABS (2015) Nutrition results - food and nutrients, 2012-13. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey. Catalogue 4727.0.55.005. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Josephine D Gwynn, Victoria M Flood, Catherine A D'Este, John R Attia, Nicole Turner, et al. (2012) Poor food and nutrient intake among Indigenous and non-Indigenous rural Australian children. BMC Pediatr 12: 12.

- (2008) Obesity - Social Report. Ministry of Social Development.

- (2017) Ministry of Health “Obesity statistics". Annual Update of Key Results 2016/17: New Zealand Health Survey.

- Sluyter JD, Schaaf D, Metcalf PA, Scragg RKR (2010) Dietary intakes of Pacific, Māori, Asian and European adolescents: the Auckland High School Heart Survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 34(1): 32-37.

- Anderson YC, Wynter LE, Butler MS, Grant CC, Stewart JM, et al. (2016) Dietary Intake and Eating Behaviours of Obese New Zealand Children and Adolescents Enrolled in a Community-Based Intervention Programme. PLoS One 11(11): e0166996.

- McElnay C, Marshall B, O’Sullivan J, Jones L, Ashworth T (2012) Nutritional risk amongst community-living Maori and non-Maori older people in Hawke’s Bay. J Prim Health Care 4(4): 299-305.

- Carol Wham, Ruth Teh, Simon A Moyes, Anna Rolleston, Marama Muru-Lanning, et al. (2016) Micronutrient intake in advanced age: Te Pua-waitanga o Nga- Tapuwae Kiaora Tonu, Life and Living in Advanced Age: A Cohort Study in New Zealand (LiLACS NZ). Br J Nutr 116: 1754-1769.

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2011) Diabetes in Canada: Fact and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Kolahdooz F, Nader F, Daemi M, Johnston N, Sharma S (2019) Prevalence of Known Risk Factors for Type Diabetes Mellitus in Multiethnic Urban Youth in Edmonton: Findings From the WHY ACT NOW Project. Can J Diabetes 43(3): 207-214.

- Johnson Down LM, Egeland GM (2013) How is nutrition transition affecting dietary adequacy in Eeyouch (Cree) adults of Northern Quebec, Canada? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 38(3): 300-305.

- Hopping BN, Mead E, E Erber, Sheehy C, C Roache, et al. (2010) Dietary adequacy of Inuit in the Canadian Arctic. J Hum Nutr Diet 23(Suppl 1): 27-34.

- Batal M, Johnson-Down L, Moubarac JC, Ing A, Fediuk K, et al. (2018) Quantifying associations of the dietary share of ultra-processed foods with overall diet quality in First Nations peoples in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario. Public Health Nutr 21(1): 103-113.

- Sangita Sharma, Elsie De Roose, Xia Cao, Anita Pokiak, Joel Gittelsohn, et al. (2009) Dietary Intake in a Population Undergoing a Rapid Transition in Diet and Lifestyle: The Inuvialuit in the Northwest Territories of Arctic Canada. Can J Public Health 100(6): 442-448.

- Sharma S, Hopping BN, Roache C, Sheehy T (2013) Nutrient intakes, major food sources and dietary inadequacies of Inuit adults living in three remote communities in Nunavut, Canada. J Hum Nutr Diet 26(6): 578-586.

- Francis Zotor, Tony Sheehy, Madalina Lupu, Fariba Kolahdooz, Andre Corriveau, et al. (2012) Frequency of consumption of foods and beverages by Inuvialuit adults in Northwest Territories, Arctic Canada. Int J Food Sci Nutr 63(7): 782-789.

- Schaefer SE, Erber E, Trzaskos JP, Roache C, Osborne G, et al. (2011) Sources of Food Affect Dietary Adequacy of Inuit Women of Childbearing Age in Arctic Canada. J Health Popul Nutr 29(5): 454-464.

- Slater J, Larcombe L, Green C, Slivinski C, Singer M, et al. (2013) Dietary intake of vitamin D in a northern Canadian Dené First Nation community. Int J Circumpolar Health 5: 72.

- Riverin B, Dewailly E, Côté S, Johnson-Down L, Morin S (2013) Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency and Associated Factors Among Canadian Cree: A Cross-sectional Study. Can J Public Health 104(4): e291-297.

- Kolahdooz F, Mathe N, Katunga LA, Beck L, Sheehy T Corriveau, et al. (2013) Smoking and dietary inadequacy among Inuvialuit women of child bearing age in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Nutrition Journal 12: 27.

- Sharma S, Cao X, Roache C, Buchan A, Reid R, et al. (2010) Assessing dietary intake in a population undergoing a rapid transition in diet and lifestyle: the Arctic Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. Br J Nutr 103(5): 749-759.

- Fukuda‐Parr S (2016) Re‐framing food security as if gender equality and sustainability mattered. In M. Leach (Eds.), Gender equality and sustainable development. London & New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 82-104.

- C Corvalán, ML Garmendia, J Jones-Smith, C K Lutter, J J Miranda, et al. (2017) Nutrition status of children in Latin America. Obesity Reviews 18(2): 7-18.

- Maurício S Leite, Andrey M Cardoso, Carlos EA Coimbra, James R Welch, Silvia A Gugelmin, et al. (2013) Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among indigenous children in Brazil: results from the First National Survey of Indigenous People's Health and Nutrition. Nutr J 12: 69.

- Jemie Walrod, Erica Seccareccia, Iván Sarmiento, Juan Pablo Pimentel, Shivali Misra, et al. (2018) Community factors associated with stunting, overweight and food insecurity: a community-based mixed-method study in four Andean indigenous communities in Ecuador. BMJ Open 8(7): e020760.

- Donald (2015) Prevalence of obesity in panama: some risk factors and associated diseases. BMC Public Health 15: 1075.

- Carvalho CA, Fonsêca PC, Priore SE, Franceschini SC, Novaes JF (2015) Food consumption and nutritional adequacy in Brazilian children: a systematic review. Rev Paul Pediatr 33(2): 211-221.

- LaRowe TL, Adams AK, Jobe JB, Cronin KA, Vannatter SM, et al. (2010) Dietary Intakes and physical Activity among Preschool-Aged Children Living in Rural American Indian Communities before a Family-Based Healthy Lifestyle Intervention. journal of the American Dietetic Association 110(7):1049-1057.

- Johnson JS, Nobmann ED, Asay E, Lanier AP (2009) Dietary intake of Alaska Native people in two regions and implications for health: the Alaska Native Dietary and Subsistence Food Assessment Project. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 68(2): 109-122.

- Hirschler V, Maccallini G, Aranda C, Fernando S, Molinari C (2013) Association of vitamin D with glucose levels in indigenous and mixed population Argentinean boys. Clinical Biochemistry 46(3): 197-201.

- Fialkowski MK, McCrory MA, Roberts SM, Tracy JK, Grattan LM, et al. (2010) Estimated Nutrient Intakes from Food Generally Do Not Meet Dietary Reference Intakes among Adult Members of Pacific Northwest Tribal Nations. Journal Of Nutrition 140(5): 992-998.

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) (2007) Macro International 2007 Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences.

- Das MB, Hall G, Kapoor S, Nikitin D (2012) India: The Scheduled Tribes. In Hall G, Patrinos HA (Eds.), Indigenous Peoples, Poverty, and Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ministry of Health and family Welfare (2018) Report of the expert committee on tribal health. Tribal health in India. Bridging the gap and a roadmap for the future.

- Bose K, Chakraborty F, Mitra K, Bisai S (2006) Nutritional status of adult Santal men in Keonjhar District, Orissa, India. Food Nutr Bull 27(4): 353-356.

- Rao T, Vijay T (2006) Malnutrition and anemia in tribal pediatric population of Purnia district (Bihar). Indian Pediatr 43(2): 181-182.

- Dutta CS, Chakraboraty T, Ghosh T (2008) Prevalence of under nutrition in Santal children of Puriliya district West Bengal. Indian Pediatr 45(1): 43-46.

- Chakraborty U, Dutta CS, Dutta G (2008) A comparative study of physical growth and nutritional status in Santal children of Ghatsila and Bolpur. Tribes Tribals 2: 79-86.

- Chatterjee S, Dhar S, Sengupta B (2011) Coexistence of haemoglobinopathies and iron deficiency in the development of anemias in the tribal population eastern India. Stud Tribes Tribals 9: 111-121.

- Ghosh-Jerath S, Singh A, Magsumbol MS, Lyngdoh T, Kamboj P, et al. (2016) Contribution of indigenous foods towards nutrient intakes and nutritional status of women in the Santhal tribal community of Jharkhand, India. Public Health Nutr 19(12): 2256-2267.

- Rao KM, Kumar RH, Krishna KS, Bhaskar V, Laxmaiah A (2015) Diet & nutrition profile of Chenchu population - a vulnerable tribe in Telangana & Andhra Pradesh, India Indian. J Med Res 141(5): 688-696.

- Bisai S, Mallick C (2011) Prevalence of undernutrition among Kora-Mudi children aged 2–13 years in Paschim Medinipur District, West Bengal India. World Journal of Pediatrics 7(1): 31-36.

- Maken T, Varte LR (2012) Nutritional status of children as indicated by z-scores of the Hmars: A tribe of N.E. India. Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology 8(1):1973-2880.

- Longvah T, Khutsoh B, Meshram II, Krishna S, Kodali V, et al. (2017) Mother and child nutrition among the Chakhesang tribe in the state of Nagaland, North‐East India. Matern Child Nutr 13(S3): e12558.

- Meshram II, Arlappa N, Balkrishna N, Rao KM, Laxmaiah A, et al. (2012) Prevalence of hypertension, its correlates and awareness among adult tribal population of Kerala state, India. 58(4): 255-261.

- Manimunda SP, Sugunan AP, Benegal V, Balakrishna N, Rao MV, et al. (2011) Association of hypertension with risk factors & hypertension related behaviour among the aboriginal Nicobarese tribe living in Car Nicobar Island, India. Indian J Med Res 133(3): 287-293.

- Mungreiphy NK, Kapoor S, Sinha R (2011) Association between BMI, Blood Pressure, and Age: Study among Tangkhul Naga Tribal Males of Northeast India. Journal of Anthropology, p. 6.

- Sharma V, Ninama R (2015) Status of Anaemia in Tribal Women of Banswara District, Rajasthan. Journal of Life Sciences 7: 1-2.

- Ghosh S (2014) Deficiency and sources of nutrition among an Indian tribal population. Coll Antropol 38(3): 847-853.

- Menon KC, Skeaff SA, Thomson C, Gray A, Ferguson E, et al. (2011) Concurrent micronutrient deficiencies are prevalent in nonpregnant rural and tribal women from central India. Nutrition 27(4): 496-502.

- Ghosh-Jerath S, Singh A, Magsumbol MS, Lyngdoh T, Kamboj P, et al. (2016) Contribution of indigenous foods towards nutrient intakes and nutritional status of women in the Santhal tribal community of Jharkhand, India. Public Health Nutrition 19(12): 2256-2267.

- Lahurnip, Iwgia (2014) A Study on the Socio-Economic Status of Indigenous Peoples in Nepal. Lawyers' Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (Lahurnip) and the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

- Dhungana RR, Devkota S, Khanal MK, Gurung Y, Giri RK, et al. (2014) Prevalence of cardiovascular health risk behaviors in a remote rural community of Sindhuli district, Nepal. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14: 92.

- Parajuli RP, Umezaki M, Watanabe C (2012) Diet Among People in the Terai Region of Nepal, An Area of Micronutrient Deficiency. 44(4): 401-415.

- Shashikala S, Kandiah M, Zalilah MS, Khor GL (2005) Nutritional status of 1–3-year-old child and maternal care behaviours in the Orang Asli Malaysia. S Afr J Clin Nutr 18: 173-180.

- Hayati MY, Ting SC, Roshita I, Safiih L (2007) Anthropometric indices and lifestyle practices of the indigenous Orang Asli adults in Lembah Belum, Grik of Peninsular Malaysia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 16(1): 49-55.

- Haemamalar K, Zalilah MS, Neng AA (2010) Nutritional status of Orang Asli (Che Wong tribe) adults in Krau Wildlife Reserve, Pahang. Mal J Nutr 16(1): 55-68.

- Chua EY, Zalilah MS, Chin YS, Norhasmah S (2012) Dietary diversity is associated with nutritional status of Orang Asli children in Krau Wildlife Reserve, Pahang. Mal J Nutr 18(1): 1-13.

- Wong CY, Zalilah MS, Chua EY, Norhasmah S, Chin YS, et al. (2015) Double-burden of malnutrition among the indigenous peoples (Orang Asli) of Peninsular Malaysia. BMC Public Health 15: 680.

- Shanita SN, Hanisa AS, Noor Afifah AR, Lee ST, Chong KH, et al. (2018) Prevalence of Anaemia and Iron Deficiency among Primary Schoolchildren in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(11): 2332.

- Pei CS, Appannah G, Sulaiman N (2018) Household food insecurity, diet quality, and weight status among indigenous women (Mah Meri) in Peninsular Malaysia. Nutrition Research and Practice 12(2): 135-142.

- Tanislaus AC, Dhanapal A, Subapriya MS, Aung HP (2018) Household Food and Nutrient Intake of Semai Aborigines of Peninsular Malaysia. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 11(4).

- Valery PC, Ibiebele T, Harris M, Green AC, Cotterill A, et al. (2012) Diet, physical activity, and obesity in school-aged indigenous youths in northern australia. J Obes, pp. 893508.

- Sheikh N, Egeland GM, Louise Johnson-Down L, Kuhnlein HV (2011) Changing dietary patterns and body mass index over time in Canadian Inuit communities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 70(5):511-519.

- Lavigne-Robichaud M, Moubarac, JC, Lantagne-Lopez S, Laouan Sidi EA, Batal M, et al. (2018) Diet quality indices in relation to metabolic syndrome in an Indigenous Cree (Eeyouch) population in northern Québec, Canada. Public Health Nutrition 21(1): 172-180.

- Khalil CB, Johnson-Down L, Egeland GM (2010) Emerging obesity and dietary habits among James Bay Cree youth. Public Health Nutr 13(11): 1829-1837.

- Thrift AG, Srikanth V, Fitzgerald SM, Kalyanram K, Kartik K, et al. (2010) Potential roles of high salt intake and maternal malnutrition in the development of hypertension in disadvantaged populations. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37(2): e78-90.

- Chakma T, Kavishwar A, Sharma RK, Rao PV (2017) High prevalence of hypertension and its selected risk factors among adult tribal population in Central India. Pathog Glob Health 111(7): 343-350.

- Egeland GM, Johnson-Down L, Cao ZR, Sheikh N, Weiler H (2011) Food Insecurity and Nutrition Transition Combine to Affect Nutrient Intakes in Canadian Arctic Communities. The Journal of Nutrition 141(9): 1746-1753.

- O’Brien DM, Thummel KE, Bulkow LR, Wang Z, Corbin B, et al. (2017) Declines in traditional marine food intake and vitamin D levels from the 1960s to present in young Alaska Native women. Public Health Nutr 20(10): 1738-1745.

- Jamieson JA, Weiler HA, Kuhnlein, HV, Egeland GM (2016) Prevalence of unexplained anaemia in Inuit men and Inuit post-menopausal women in Northern Labrador: International Polar Year Inuit Health Survey. Canadian Journal of Public Health 107(1): e81-e87.

- Amanda AK, Batal M, David W, Sharp D, Schwartz H, et al. (2018) Risk assessment of dietary lead exposure among First Nations people living on-reserve in Ontario, Canada using a total diet study and a probabilistic approach. Journal of Hazardous Materials 344: 55-63.

- Amanda K, Juric MB, David W, Sharp D, Schwartz H, et al. (2017) A total diet study and probabilistic assessment risk assessment of dietary mercury exposure among First Nations living on-reserve in Ontario, Canada. Environmental Research 158: 409-420.

- Frances E Thompson, Timothy S McNeel, Emily C Dowling, Douglas Midthune, Meredith Morrissette, et al. (2009) Interrelationships of Added Sugars Intake, Socioeconomic Status, and Race/Ethnicity in Adults in the United States: National Health Interview Survey. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 109(8): 1376-1383.

- Mungreiphy NK, Kapoor S (2010) Socioeconomic Changes as Covariates of Overweight and Obesity Among Tangkhul Naga Tribal Women Of Manipur. North-East India 42(3): 289-305.

- Welch JR, Ferreira AA, Santos RV, Gugelmin SA, Werneck G (2009) Nutrition Transition, Socioeconomic Differentiation, and Gender among Adult Xavante Indians, Brazilian Amazon. Human Ecology New York 37(1): 13-26.

- Ma Y, He FJ, MacGregor GA (2015) High Salt Intake Independent Risk factor for Obesity. Hypertension 66(4): 843-849.

- Jiang S, Lu W, Zong X, Ruan H, Liu Y (2016) Obesity and hypertension. Exp Ther Med 12(4): 2395-2399.

- Briggs MA, Petersen KS, Kris-Etherton PM (2017) Saturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease: Replacements for Saturated Fat to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. Healthcare (Basel) 5(2): 29.

-

Shruti Sharma, Ravi Naidu. Mapping of Dietary Risks in Indigenous People: A Scoping Review. Glob J Nutri Food Sci. 3(5): 2022. GJNFS.MS.ID.000572.

-

Dietary risks, Review literature, Indigenous nutrition, Indigenous diet, Indigenous health, dietary patterns, Traditional food, Diabetes, Hypertension, Cardiovascular disease, Overweight, Obesity, Hypertension, Undernutrition, Malnutrition

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.