Short Communication

Short Communication

Legal Consultancy in Forensic Archaeology: An Introduction to Italian Regulations and Professional Ethics

Pier Matteo Barone*

1Department of Archaeology and Classics Program, American University of Rome, Italy

2Department of Forensic Geoscience, Italy

3Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forensi (AcISF), Italy

Pier Matteo Barone, Archaeology and Classics Program, American University of Rome, Italy.

Received Date: February 15, 2019; Published Date: February 21, 2019

Abstract

In recent years, professional archaeologists have increasingly been called upon by civil and criminal Courts to act as courtappointed experts all over the world. In Italy, in particular, this professional profile seems to be less popular due to some misunderstandings related to both the tasks and the roles. This article will clarify some legal aspect of being a forensic archaeologist in Italy from theoretical and practical points of view.

Keywords: Forensic archaeology; Italy; Court; Law; Consultancy; Expert

Introduction

The development of the role of archaeologist in the field of forensics can be linked to two main factors: judges are becoming increasingly aware of the fact that archaeological expertise can play a crucial role in shedding light on various cases of civil and criminal offenses [1]. Normally, forensic archaeologists are employed to search for missing persons and/or to find/recover said persons. However, reports of archaeological/cultural offenses (such as violations of the Italian Code of Cultural Heritage or Article 733 of the Italian Penal Code) are on the rise, thus requiring the involvement of archaeologists or cultural heritage experts [2,3].

In this context, it follows that professional archaeologists will become increasingly involved in the field of forensics. They will require the appropriate knowledge of certain regulatory and ethical matters in order to carry out incontestable expert work and provide the Courts with reports of a high standard in terms of both form and substance [1]. In both civil and criminal cases, Judges have the power to appoint a professional, expert or technician as their assistant when they need to settle complex technical issues, carry out investigations or acquire data or judgments that require specific technical, scientific or artistic skills (Article 221 of the Italian Code of Criminal Procedure, hereafter CCrP, and Article 61 of the Italian Code of Civil Procedure, hereafter CCiP) [1].

The role of appointed experts is not simply to report to the Judge, but rather to provide the Judge with knowledge that the latter does not possess, such as a scientific rule or technique that may be necessary in the course of proceedings to verify and/or evaluate a situation or a problem [1-4]. Within this framework, professionals appointed by Judges act on the basis of the proceedings and in the higher interests of justice. Their technical reports must therefore be neutral in nature and not classifiable as either in favor of or against the defendant or the parties. These reports fall outside the scope of the principle of party disposition and must essentially be placed at the Judge’s discretion. For this reason, those acting as expert assistants to Judges in both civil and criminal cases must take an oath when accepting the task: “to carry out the tasks entrusted to them faithfully and well with the sole aim of making the truth known to the judge(s)” (Art. 193 of the CCiP). This oath obliges the Judge’s assistant to take on certain responsibilities and to keep strictly to ethical and moral rules [1].

It should be noted that professionals who belong to the Register of Civil Court Experts and/or the Register of Criminal Court Experts cannot refuse to fulfill a mandate assigned to them by a Judge (Art. 63 of the CCiP and Art. 221 of the CCrP), except in cases where the grounds for mandatory abstention as required by law apply (Art. 51 of the CCiP and Art. 36 of the CCrP), in which case the professional is obliged to declare it. As such, experts who apply for membership of the aforementioned registers essentially consent in advance to carrying out these tasks if requested [1-4]. The following sections illustrate the distinction between the tasks assigned in civil and criminal cases in order to then define the relative responsibilities.

Tasks assigned to CTUs

In civil cases, the expert appointed by the Judge is known in Italian as a “Consulente Tecnico d’Ufficio” (an official legal consultant, hereafter CTU); their appointment is regulated mainly by Articles 61 and 191 of the CCiP. The CTU must be chosen from the professionals listed in the appropriate Register of Experts at each civil Court. Judges are not obliged to select a CTU from the aforementioned register; they can nominate an expert registered with a different court or one who is not registered at all [3,4]. At the hearing set for the taking of the oath and the appointment of the CTU, the Judge, in addition to reminding the expert of the importance of his/her tasks and hearing the oath, takes additional measures such as: determining, together with the CTU, the start date, time and place for the expert’s work; explaining the question and defining the expert’s investigative powers; authorizing the CTU to collect paperwork from the parties or copies of documents from the court files where necessary; setting a deadline for the submission of the draft technical report to the parties and for the filing of the final technical report; assigning the task in order to instigate the attempt at mediation between the parties; making a decision on the request for an extension to the deadline for the appointment of party-appointed experts (where this deadline has not already passed); authorizing any requests from the CTU (use of own vehicle, collaboration with assistants, access to places, advance for expenses, etc.) [1,3,4].

The CTU’s work involves three phases:

1. the CTU’s report (complete but in draft form) is sent to the Parties by the deadline set by the Judge during the task appointment hearing

2. the Parties send the expert their observations on the CTU report by the following deadline set by the Judge

3. by the following deadline set by the Judge, the expert must file the report, the parties’ observations and a brief final assessment of these observations at the office of the clerk of the Court [1,3,4].

When finalizing their work, CTUs must therefore take into account the observations of the parties, acknowledging them in the main body of the final report and providing answers or clarifications as necessary. Once the CTU’s report has been filed, the Judge is not strictly bound to adhere to the conclusions reached by the CTU. In fact, the Judge may: adhere to the CTU’s conclusions without giving any particular reason; deviate from them, giving an appropriate reason; adhere to the CTU’s conclusions while providing an appropriate reason if the court-appointed expert’s report did not respond to criticisms raised by a party-appointed expert [3,4].

Tasks assigned to experts

In criminal cases, the professional appointed by the Judge is known in Italian as a “Perito” (hereafter simply Expert); their appointment is regulated by Articles 220 to 232 and 508 of the CCrP. The Expert must be chosen from the professionals listed in the appropriate Register of Experts at each criminal Court. As a strictly secondary consideration, persons with particular expertise in the field may be chosen [1]. An expert opinion can be provided at various stages of a criminal trial: at the special evidentiary hearing; at the preliminary hearing; at the simplified and shortened proceedings; at the trial; at the enforcement proceedings; at the rehearing [1, 2]. At the hearing where the task is to be assigned to the Expert, the Judge, having ascertained the Expert’s details, asks him/her if any of the conditions for incapacity or incompatibility apply, informs him/her of the obligations and responsibilities set out by criminal law (including secrecy in carrying out expert work) and invites him/her to take the following oath: “I, being aware of the moral and legal responsibility that I take on in carrying out this task, undertake to fulfill my duty with the sole aim of making the truth known”. Moreover, during the same hearing, the Judge: formulates the questions after listening to the court-appointed Expert, the party-appointed experts, the State Prosecutor and the counsel for the defense; authorizes the Expert to examine the records, documents and evidence produced by the parties, which the law states must be included in the trial file; determines that the Expert must immediately proceed with the necessary investigations and answer the questions by way of an opinion given on the record and/ or grants a deadline (of which the parties and appointed experts must be informed), which may not exceed ninety days and may be extended by the Judge; authorizes any requests from the Expert (being present for the questioning of the parties and the taking of evidence, using trusted assistants, etc.). With regard to the work of the Expert’s collaborators, the regulations specifically indicate that this should be limited only to carrying out material activities not involving assessment and evaluation, and to laboratory analysis (Art. 228 of the CCrP) [1,2].

Art. 227 of the CCrP establishes that the Expert’s opinion must be expressed orally, with statements placed on record, and may only be expressed by means of a written report in exceptional circumstances. Although in practice, this second way of clarifying the results of the Expert’s work constitutes the rule, filing the written report remains secondary with respect to the Expert’s presentation of his/her opinion in oral form. The reading of the Expert’s report is therefore arranged only after the Expert has been questioned orally. This is a necessary condition for the admission of evidence (Art. 511 of the CCrP); in fact, according to law (Art. 501 of the CCrP), oral questioning of the Expert at the trial falls within the provisions set out with regard to the questioning of witnesses, and a failure to carry this out results in the evidence being inadmissible, or at the least in interim nullification due to the violation of the parties’ rights of defense [1].

Ethical Approach and Responsibilities of CTUs and Experts

Judges’ assistants must fulfill certain essential requirements, including:

i. proven and incontestable professional experience

ii. knowledge of legal procedures in order to adhere to said procedures and see to it that the parties’ rights are respected

iii. the ability to analyze and synthesize information

iv. continuing professional development

v. integrity and impartiality

vi. independent judgment [5]

The expert opinions provided, and the work carried out by the CTU/Expert must be incontestable from a procedural standpoint. It is to be emphasized that the duty of the Judge’s assistant is not to provide legal assessments or ascribe responsibility, but rather to develop the technical foundations on which the judgment of the competent Judge will be based [1,5]. In performing their duties, CTUs and Experts can incur three types of liability: disciplinary liability, civil liability and criminal liability. The disciplinary liability of CTUs/Experts is assessed by the presiding Judge of the Court and concerns the following aspects: not having displayed “exemplary moral conduct” (regarding cases not necessarily related to violations of the CTU’s task); not having fulfilled the obligations resulting from the assignments received (Art. 19 Implementing Provisions of CCiP and Arts. 69 and 70 Implementing Provisions of CCrP). The disciplinary sanctions applicable to CTUs and Experts are: a warning; suspension from the register for a period not exceeding one year; removal from the register (Art. 20 Implementing Provisions of CCiP and Art. 70 Implementing Provisions of CCrP) [5].

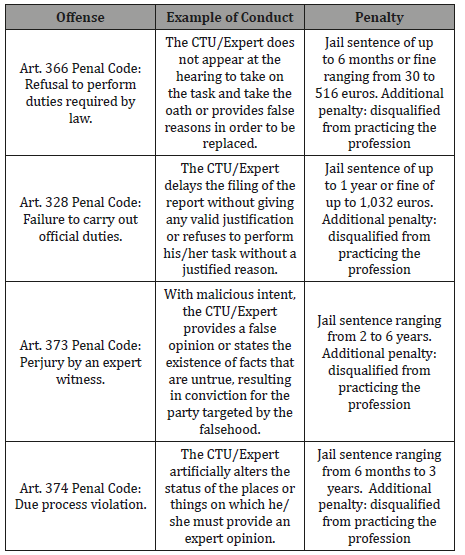

Civil liability obliges the CTU or Expert to pay compensation for damage caused to the parties due to his/her conduct in having violated the duties of diligence and correctness or in not having carried out the task faithfully and well. This is based on Art. 64 of the CCiP, according to which “CTUs who display gross negligence in performing the deeds asked of them will be punished with a period of imprisonment of up to one year or a fine of up to 10,329 euros [...] In any case, compensation is due for the damage caused to the parties” [2]. CTUs and/or Experts are criminally liable due to the fact that, as the Judge’s assistant, they hold the position of public official in accordance with the definition given in Art. 357 of the Italian Penal Code, according to which “for the purposes of criminal law, public officials are those who exercise a public legislative, judicial or administrative function”. The types of criminal offense linked to this particular position (e.g. embezzlement, extortion, corruption, abuse of power, forgery of the origin or content of documents, etc.) therefore apply to Judges’ assistants. Table 1 shows the most common types of criminal offenses committed by CTUs and Experts [1] (Table 1).

the offense of perjury by an expert witness, governed by Art. 373 of the Italian Penal Code, according to which “experts or interpreters who, having been appointed by the judicial authority, give false opinions or interpretations, or state facts that do not conform to reality, will be subject to the penalties set out in the previous article . In addition to being banned from holding public office, those convicted will also be disqualified from the profession or craft” [1, 4]. It should be noted that the Expert can commit the offense of perjury by an expert witness by: concealing his/ her incompetence; concealing the fact that he/she is temporarily or legally incapable of drawing up the expert opinion; failing to mention that he/she fulfills the conditions for incompatibility; not engaging in the necessary investigations; failing to provide certain evaluative elements or providing interpretations summarized in statements that do not correspond to reality [1,4].

Table 1: Main types of criminal offenses committed by CTUs and Experts (after [4]).

Generally, for cases in which a criminal offense committed by a CTU or an Expert must be investigated, the Judge reserves the right to appoint his/her own Expert. Naturally, the Expert appointed to establish the existence of a criminal offense in the work or expert opinion of another Expert or CTU must necessarily exercise the same profession as the expert being investigated. This particularly delicate matter determines the Judge’s decision, in choosing an Expert, to appoint a professional who is not a member of the same regional professional Register as the expert under investigation. [1- 5]

Ancient or not?

In one civil case, the assigned CTU, having provided an expert opinion, was reported for perjury by one of the parties, according to whom the expert opinion contained false claims. The CTU had been asked to ascertain whether some archaeological finds, discovered in the alleged possession of certain civilians in a field, were of genuine archaeological value or not. In response to the judge’s question, the CTU stated that, based on his experience and an autopsy analysis, the finds could be considered ancient and therefore of cultural value.

The judge for the preliminary investigations then ordered an expert opinion to establish if there was adequate evidence in the CTU’s report for a committal to trial. The Expert was asked to ascertain whether the content of the CTU’s technical report contained false claims or interpretations summarized in statements that did not correspond to reality, or any clear disparities with respect to historical facts or data ignored in the evaluation and overall interpretation of events. The Expert highlighted several critical issues in the CTU’s report. Firstly, the CTU had signed an official report with a date prior to the alleged crime committed (a typical copy/paste error that indicates a certain degree of superficiality). Subsequently, this report presented an assessment of the antiquity and authenticity of the find based solely on the alleged experience of the CTU and on a very trivial autopsy analysis of the finds, omitting not only a possible comparison with similar materials of the same age, but also (and above all!) an archaeometric analysis of the aforementioned finds in order to obtain and submit to the judges scientific and quantifiable data to corroborate (or refute) the authenticity/antiquity of the remains. Furthermore, the CTU’s lack of knowledge of basic procedures led to the omission of a photographic appendix within the report, and also to a superficial approach during the trial, with the CTU only presenting black and white photographs of the finds to the Judge.

The CTU’s massive cognitive bias, whereby any question raised to him by the judge always had to be answered at the expense of the defendant(s), obviously led to an erroneous analysis procedure and an embarrassingly superficial approach. In conclusion, the expert opinion highlighted that the CTU, in viewing the finds and describing all the elements and circumstances useful in order to establish their authenticity/antiquity, had reported false claims and interpretations summarized in statements that did not correspond to reality in the overall content of the expert report, and that the CTU had often gone so far as to make baseless statements not backed up by objective evidence. Moreover, some of the CTU’s arguments showed clear discrepancies with respect to historical facts (see the comments about the closing date of the document). Finally, the CTU had ignored data found in the case records and documents; this data should have played a fundamental role in the overall evaluation and interpretation of the events and had an impact on the final technical considerations. The CTU had not discussed this data with appropriate technical arguments or counter-arguments in order to refute its value and/or express his disagreement or refusal.

Conclusion

It seems clear that in the work of CTUs and Experts, the morals and professional ethics of the assigned technician are of primary importance, not only to avoid “unpleasant incidents” that could undermine the practice of the profession, but also to provide judges with a means that is correct in terms of both procedure and substance and that can aid justice and thus society..

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Brescia G (2018) Manuale del perito e del consulente tecnico nel processo civile e penale, Maggioli Editore, Rimini.

- Consiglio Nazionale dei Dottori Commercialisti e degli Esperti Contabili (2012) La perizia e la consulenza tecnica nel processo penale, CNCDEC, Roma.

- Secchi E (2011) La CTU nel processo civile, Percorsi giurisprudenziali, Ed. Giuffrè, Milano.

- Bujani E (2012) La Perizia e la Consulenza Tecnica nel Processo Civile, Corso di Formazione per CTU, Ordine degli Ingegneri della Provincia di Pistoia, Pistoia.

- Barone PM, Groen M (2018) Multidisciplinary Approaches to Forensic Archaelology. Topics discussed during the European Meetings on Forensic Archaeology (EMFA).

-

Pier Matteo Barone. Legal Consultancy in Forensic Archaeology: An Introduction to Italian Regulations and Professional Ethics. Glob J of Forensic Sci & Med 1(3): 2019. GJFSM.MS.ID.000511.

-

Forensic archaeology, Italy, Court, Law, Consultancy, Expert, investigation, criminal cases, evidence, Expert's opinion, Defense.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.