Mini Review

Mini Review

The New New? Curated Second Hand as a (Re)Construction Principle for Notre-Dame de Paris

Daniel Stockhammer, Assistant Professor for Heritage & Cycle- Oriented Architecture, University of Liechtenstein, Liechtenstein.

Received Date: April 22, 2021; Published Date: May 17, 2021

Mini Review

In view of ever-increasing environmental and climate problems, a sustainable approach to dealing with the world’s resources is indeed being discussed, but the focus is placed primarily on the conservation of physical resources and much less on the reuse of intangible, non-reproducible cultural resources. In architecture, however, recycling cannot be reduced to atoms because both material and immaterial values are embodied within residual building mass [1]. When designing, reuse entails working and building with the past and its meaning for today. The more we understand the existing, “the less we must stand in opposition to it,” says Hermann Czech, “and the easier it will be to understand our decisions as a continuation of a whole” [2].

As a clever recycling of semiotics and both history and narratives, spoliation and assemblage are, according to our thesis, capable of expanding the principle of reuse and repurposing from the level of materiality to immaterial values, and of calling into question the understanding of an architecture of uniqueness, originality, and insularity. An intellectual game using the example of Notre-Dame de Paris creates an impetus to re-examine the used not only with an admiring or averted eye, but also with an eye for how to utilize it.

Categories of the Twentieth Century

How little the existing built fabric has been regarded as an immaterial resource to date and how much the discourse still is determined by categories from the last century can be exemplified by the reconstruction debate surrounding the Paris cathedral: On the one side are the so-called progressive forces, driven by the potent myth of novel forms, following the modern paradigms of replacement (buildings), authorship, originality, and establishing distance from the old. This stands in contrast to the ideal of reconstruction, a longing that wrestles with the questions of “how” or “which original” and “of what”; because ultimately, as Georg Simmel asserts, only the past itself, “with its destinies and transformations,” can be “gathered into this instant of an aesthetically perceptible present” [3].

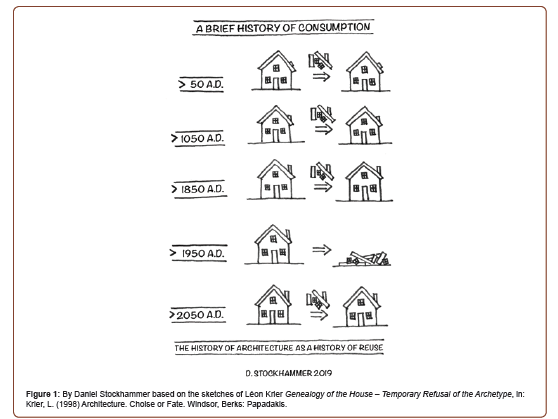

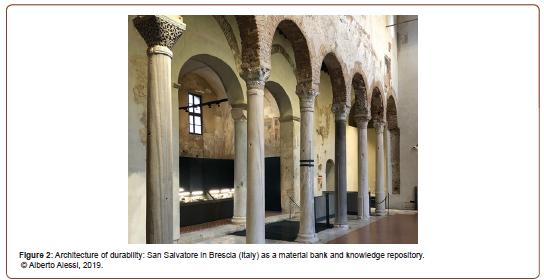

Yet with the principle of reuse and repurposing – addressing the contradictions and frictions between different epochs, ways of thinking, and patterns of use – both positions, whether so-called restoration or subsequent addition, have excluded a central theme of cathedral architecture. The reason is that, as Georg Mörsch writes, for new buildings as well as reconstructions, “we always give only the little that we know, and often only that which we need” [4] (Figures 1,2).

We is more – A Communal Process

Reuse is more complex than building something new and is “by definition a subject that lies between disciplines,” [5] according to Arnold Esch. Traditionally, it has been the task of archaeology and building research to temporally and spatially map out displaced parts, the missing pieces in the old context. Questions about the motive and the circumstances of the translocation are dealt with by historical research, and the new context is usually the subject of art history [6]. Lastly, the thoughtful clarification of complexity and design repercussions falls within the scope of architecture, in collaboration with the arts of engineering and craft. Thus, designing with the used requires the combined efforts of many disciplines; it necessitates a communal, open process where all the contributors’ skills and perspectives have to be united to establish shared insight and emergence. But for those who design buildings, to regard their undertakings as the project (and intellectual property) of many also means a shift from being a creator to a contributor; it means to rethinking traditional certainties and concepts, renegotiating role models, and asking the question: How can the design of the processes themselves become a central task of the scholarly and design disciplines and how can an understanding of reuse that is developed from within architecture influence other fields related to construction (urban development, engineering, monumental preservation, etc.)?

The Existing Built Fabric as a Repository of Resources – Transmission as Program

The spoliation of an intact building that still functions and provides utility in order to hand down tradition would unquestionably be foolish. But should its ravaging be prohibited when the building is about to be demolished? Would it not make sense in that case to despoil material and know-how from other epochs and make it fruitful for today’s ventures?

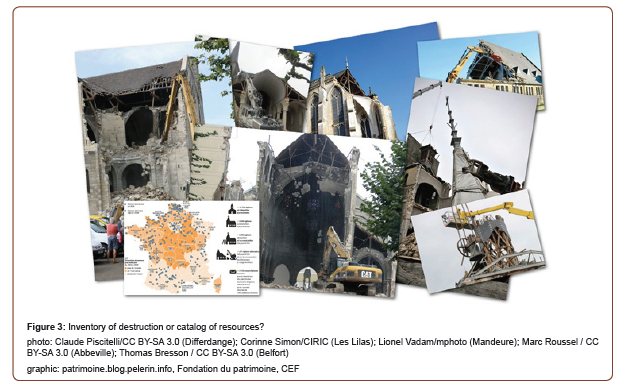

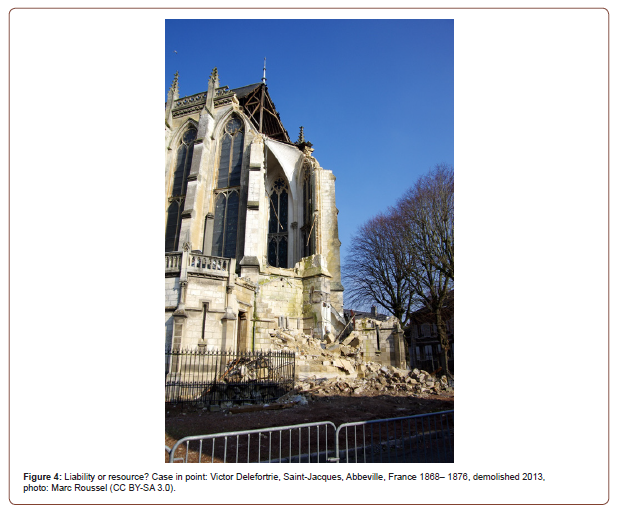

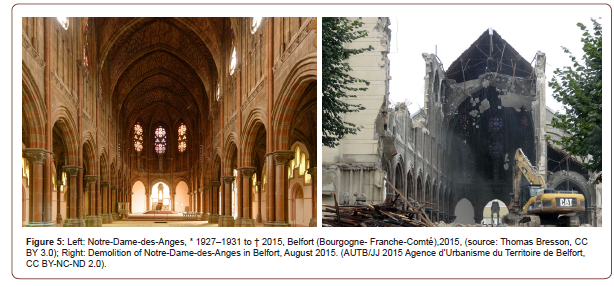

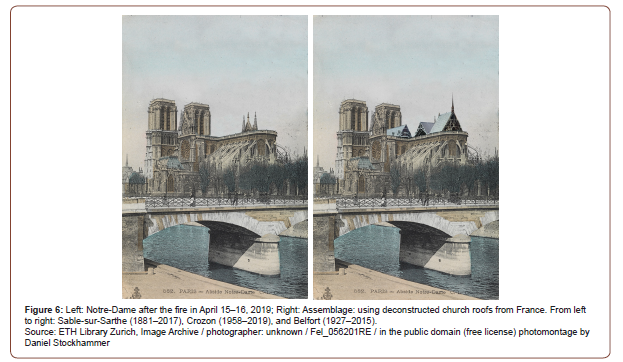

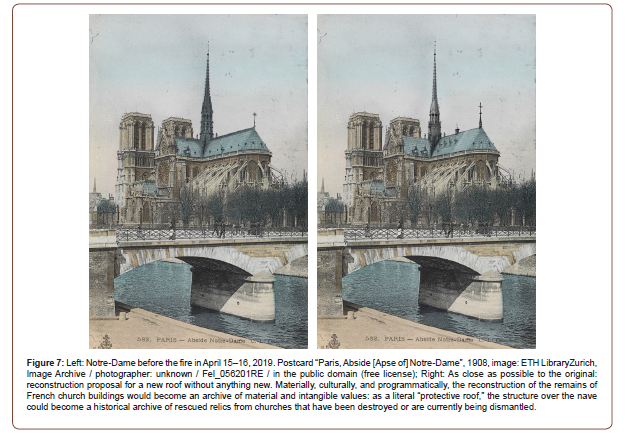

Societal changes and a lack of funds for maintenance make France’s stock of church buildings a particular focus of such thoughts. After all, France’s “Loi Combes,” the 1905 law on the separation of church and state, had declared the church and religious communities in France to be institutions under private law. Ever since then, the state no longer collects church taxes, is the owner of all ecclesiastical buildings erected before 1905 (especially the churches) and is responsible for their maintenance. The long-term implications can be seen today in the condition of many of these more than 40,000 houses of God. Valuable edifices, some of which are centrally located, cannot be sufficiently maintained anymore, lose their utility, and are ultimately razed [7]. In view of an image that alternates between (neglected) conservation culture in general or (over)protection in particular, we should pose the question of whether reconstruction of the Notre-Dame de Paris should be given further thought and discussed within the framework of all the threatened church buildings in the country: as an assemblage of France’s derelict stock of church buildings (Figures 4-7).

Afterlife – Paths to Ambiguity and Multiplicity of Meaning

Everything is exposed to both the peril and the opportunity of reuse and repurposing. In the spirit of historicism – the architectural style of many of the razed churches – the 2019 blaze that ravaged Notre Dame should be seized as an opportunity to create something new from the old; not as a singular event in its own temporal domain but understood diachronically in its entire historical-cultural extent. One may “survive” a disaster “and then stand around; yet that says nothing about what happens afterward.” But an afterlife by means of clever recomposition is far more, “that which lives on continues to have an effect, it changes itself and other things, it lives on” [8]. The continued creative and qualitative utilization of the used is able to ignite new and surprising aspects in architecture, thereby contributing to: the conservation of material resources and knowledge of building culture, safeguarding the continuity of history, places, and buildings; promoting a culture of remembrance and identity, as well as fostering social continuity, cooperation, and a sense of community; producing architectural relevance through superimposition, complexity, and multiplicity of meaning (instead of form) and demanding and thus nurturing a long-term orientation through the simplicity and longevity of constructive design, building materials, and technology.

Reuse as a Design Principle – From Project to Process

Applying the principle of reuse and repurposing to the example of the redesign of Notre Dame would mean understanding the reconstruction not as a self-contained project in itself but as a process, determined by continual uncertainty, that could be categorized into different fields of work, such as:

1. the inventory – the stock of endangered church buildings in France would be logged and then documented and preserved as a repository of building parts;

2. the kit of parts – the material bank would become the basis for an interdisciplinary, broad-based discourse on the selection of the building parts, their meanings, and their histories; and

3. the assemblage – the artistic consequence of recomposing the parts–would lastly be negotiated by architecture together with the arts of engineering and craft.

This would be done with the goal of assimilating subtle irregularities in the use of materials and in the formal design of the roof and the crossing tower, slight variations in the ridge height, or moments of surprise from transposed relics such as ridge turrets and dormers – the total sum of the spoliations – to form a new, visually harmonious whole. The end result would be a new building with no new parts, a ‘new’ way of building that breaks away from the dogma of the new build. Materially and culturally as well as programmatically, reconstruction would become a growing archive of resources: As a literal ‘protective roof,’ the roof construction above the nave could become a walk-through repository – for rescued relics and the remnants of French church buildings that have been destroyed or are currently being dismantled – where the contents are on display. Complementing this, a central exhibition space above the transept would serve as a venue for discussing individual specimens and curated collections [9].

According to Walter Benjamin, it is repeatedly necessary to reclaim “tradition anew from the conformism which is on the point of overwhelming it” [10]. A reversion to and consciousness of the principle of reuse and repurposing is not tantamount to holding conservative values, but is instead the overcoming of onedimensionality, transience, and the cult of authorship through emergence, permanence, and transdisciplinary dialogue.

“Anyone wishing to convey new ideas cannot simultaneously make use of a new language to do so,[11] says Czech. Hence, we should no longer confront the challenges of the twenty-first century with architecture as an imperative, but with building culture as a verb.

Acknowledgement

This essay is based on results from the research project “Renewable Architecture” funded by Liechtenstein’s API Foundation and from the upcycling studio “Hi story! Notre-Dame reloaded” conducted by Daniel Stockhammer and Cornelia Faisst at the Institute of Architecture and Planning at the University of Liechtenstein in the winter semester, Germany.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Uta Hassler (1999) Particularly noteworthy in this regard is the research of Uta Hassler. Conversion, mortality and long-term dynamics. In: Uta Hassler, Niklaus Kohler, Wilfried Wang (eds.): Conversion: About the future of the building stock, pp: 39-59.

- Hermann Czech, Zur Abwechslung (1973) In: Hermann Czech: Zur Abwechslung: Ausgewählte Schriften zur Architektur, Vienna 1996 (1977), pp: 76–79. Translated by Michael Loudon as “For a Change,” In: Kenneth Frampton (ed.), A New Wave of Austrian Architecture, Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) catalogue 13, New York, pp. 59-60. On the topic of reconstruction, refer also to other brilliant essays written by Czech from the 1960s onward, collected in: Hermann Czech, Essays on Architecture and City Planning, (edn.) and trans. by Elise Feiersinger, Zurich 2019.

- (2019/20) This essay is based on results from the research project “Renewable Architecture” funded by Liechtenstein’s API Foundation and from the upcycling studio “Hi story! Notre-Dame reloaded” conducted by Cornelia Faisst and Daniel Stockhammer at the Institute of Architecture and Planning at the University of Liechtenstein in the winter semester, Germany.

- Georg Simmel (1907) Die Ruine: Ein ästhetischer Versuch. In: Der Tag, no. 96, Berlin, Translated by David Kettler in “Two Essays: The Handle, and The Ruin,” Hudson Review, 1958.

- Georg Mörsch (1998) Ist Rekonstruktion erlaubt?. In: Adrian von Buttlar, Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper, Michael S Falser (Eds.), Denkmalpflege statt Attrappenkult: Gegen die Rekonstruktion von Baudenkmälern; Eine Anthologie. Bauwelt Fundamente, 2010, 146, pp. 39-41.

- Arnold Esch (2005) Reuse of Antiquity in the Middle Ages: The Archaeologist's View and the Historian's View. Berlin, Germany, pp: 1-12.

- On the different tasks of scholarly disciplines, Esch, pp: 11–60.

- On this topic, see especially Observatoire du Patrimoine Religieux’s inventory of endangered and demolished churches in France and information from Fondation du Patrimoine. Some of the most recent demolitions in France include Notre-Dame-du-Rosaire, Les Lilas (Île-de-France), 1887–2011; Notre-Dame-des-Anges, Belfort, 1927–2015; Sainte-Thérèse de Beaulieu, Mandeure, 1936-2015; and Notre-Dame-de-Gwel-Mor, Crozon, 1958-2019, among many others.

- Arnold Esch (see note 6), pp: 1-21.

- The program for this potential use builds on research by Berta Beketova and Hanna Kuzniatsova, students from the previously mentioned studio (see note 3).

- Walter Benjamin (1940) Über den Begriff der Geschichte. In: Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften (ed.) by Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhäuser, Frankfurt / M. 1978, 1-2, p. 695. Essay translated by Dennis Redmond in 2005 as “On the Concept of History,” marxists.org, accessed September 1, 2020.

- Hermann Czech (1989) Transformation, The Cultural Aspect in Essays (see note 2), pp. 185-191.

-

Daniel Stockhammer. The New New? Curated Second Hand as a (Re)Construction Principle for Notre-Dame de Paris. Cur Trends Civil & Struct Eng. 7(3): 2021. CTCSE.MS.ID.000662.

-

Construction, Notre-Dame, Environment, Buildings, Resources

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Mini Review

- Categories of the Twentieth Century

- We is more – A Communal Process

- The Existing Built Fabric as a Repository of Resources – Transmission as Program

- Afterlife – Paths to Ambiguity and Multiplicity of Meaning

- Reuse as a Design Principle – From Project to Process

- Acknowledgement

- Conflicts of Interest

- References