Research Article

Research Article

Primary Osteosarcoma of Testis and Para-Testicular Tissues: A Review and Update of the Literature

Anthony Kodzo Grey Venyo*

Department of Urology, North Manchester General Hospital, UK

Anthony Kodzo Grey Venyo, Department of Urology, North Manchester General Hospital, UK.

Received Date: May 13, 2019; Published Date: June 06, 2019

Abstract

Osteosarcoma of the testis and para-testicular tissue is a terminology that refers to a malignant tumor that contains pure osteoid forming malignant cells with no skeletal origin that affect the testis or para-testicular tissues. These tumors tends to present as an intra-scrotal or testicular mass which is non-specific. It may also present in association with a hydrocele. Clinical examination may reveal a firm to hard mass in the testis or in the affected para-testicular tissue. The inguinal glands may be normal but on rare occasions there may be lymph node enlargement in advanced cases. If there is an associated hydrocele there may be clinical examination evidence of a hydrocele. The full blood count, serum urea and electrolytes and liver function tests would tend to normal unless there are un-related pathologies which would need to be investigated accordingly. Nevertheless, if there are multiple liver metastases the liver function test results may show derangement in one or more elements of the liver function tests. The serum Beta Human Chorionic gonadotrophin, alpha fetoprotein, and lactate dehydrogenase levels would tend to normal unless the osteosarcoma is associated with a synchronous Germ cell tumor which does happen occasionally. Radiology imaging could show evidence of a heterogeneous mass within the testis in the case of a testicular tumor or in an intra-scrotal area at the site of the lesion and the mass tends to be associated with calcification. Treatment tends to be radical orchidectomy for localized tumors involving the testis only, but para-testicular osteosarcomas tend to be treated by radical orchidectomy plus en bloc excision of the para-testicular tissue. If there is evidence of metastasis then adjuvant therapy can be given. Gross examination of specimens of an excised osteosarcoma of the testis would tend to show a well-circumscribed, firm, solid, whitish tan, expansile mass which had compressed the surrounding parenchyma of the testis. Microscopic examination of primary osteosarcoma of the testis specimen would tend to show sheets of pleomorphic round to spindle cells that contain prominent nucleoli, areas of osteoid and scattered areas of mineralization, high mitotic activity and atypical mitosis, osteoid and at times osteoclasts among the area of osteoid. Immunohistochemistry studies of osteosarcoma of the testis or any para-testicular structures would tend to show the tumor cells stain positively for vimentin, but the tumor cells would stain negatively for: smooth muscle actin, CD34, cytokeratin, desmin, inhibin, myo-D1, and S-100 proteins.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma; Testis; Epididymis; Tpermatic cord; Tara-testicular tissues; Vimentin; Radical orchidectomy; Spindle cells; Pleomorphic; Computed tomography scan; Magnetic resonance imaging scan; Ultrasound scan

Introduction

It has been stated that genitourinary sarcomas are not common in adults and that they had been estimated at less than 2.7% of all sarcomas. [1-2] It had also been iterated that extra-osseous paratesticular soft tissue osteosarcoma is an extremely uncommon type of malignant tumor. Hong R, et al. [3] stated that due to the rarity of para-testicular osteosarcoma; its histogenesis; treatment; and as well as its specific survival rates were not available. Osteosarcoma of the testis refers to a testicular tumor that is composed of pure osteoid forming malignant cells with no skeletal origin. Gordetsky J [4] Due to the extreme rarity of primary and metastatic osteosarcomas of the testis and the scrotal contents; it would be envisaged that majority of clinicians globally would not be familiar with the presentation; diagnosis; treatment and biological behaviour of the disease. The ensuing article on primary osteosarcoma of testis and para-testicular tissues: a review and update of the Literature is divided into two parts: (A) Overview and (B) Miscellaneous narrations; summations; and discussions related to case reports; case series; and studies related to osteosarcomas of the testis and para-testicular tissues.

Aim

To review and update the literature on primary osteosarcomas of the testis and Para testicular tissues.

Method

Internet data bases were searched including Google; Google Scholar; Yahoo and PUBMED. The search words that were used included: Primary osteosarcoma of testis; osteosarcoma of testis; primary osteosarcoma of epididymis; osteosarcoma of tunica vaginalis; osteosarcoma; osteosarcoma of tunica albuginea; osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord; para-testicular osteosarcoma; intra-scrotal osteosarcoma; and scrotal content osteosarcoma.

Result- Review and Update of Literature

Overview

Definition/general comments: Osteosarcoma of the testis refers to a tumor of the testis which is comprised of pure osteoid forming malignant tumoral cells which do not have any skeletal origin [4].

Epidemiology

• Pure primary osteosarcoma is an extremely uncommon disease [pathology outlines]

• The sporadic cases of osteosarcoma of the testis which had been reported had been reported in males whose ages had ranged between 30 years and 78 years and the mean age of the patients was 59 years [4].

Pathophysiology

• It has been postulated that osteosarcoma of the testis; usually tends to be derived from sarcomatous transformation of germ cells tumors which are also called teratomas [4].

• It had also been suggested that osteosarcoma of the testis could also develop as a component of malignant mixed sex cord / stromal tumor [4].

• It has been additionally stated that pure primary osteosarcomas of the testis without teratoma elements had been reported in which it had been indicated that the tumors could arise from primitive stromal cells of the testis or from metaplastic stromal cells [2,4-5].

Clinical features

Presentation

• Primary osteosarcoma of the testis tends to present as an intra-scrotal mass or a mass within the testis [4].

Laboratory investigations

a. Urine

• Urinalysis; urine microscopy; urine culture and sensitivity form part of the initial screening assessments of patients who have primary or metastatic intra-scrotal osteosarcomas bit generally the results would tend to be normal but if there is any evidence of urinary tract infection it would be treated with the most appropriate antibiotics based upon the antibiotic sensitivity pattern of the cultured organism and the allergy status of the patient to improve the general condition of the patient.

b. Hematology blood tests

• Full blood count and coagulation screen are routine tests that tend to be undertaken as part of the general assessment of patients who have primary intra-scrotal osteosarcoma and generally the results would tend to be normal but if there is any abnormality found it would be investigated appropriately and the most appropriate treatment would be given to improve upon the general condition of the patient.

• Full blood count and coagulation screen are routine tests that tend to be undertaken as part of the general assessment of patients who have primary intra-scrotal osteosarcoma and generally the results would tend to be normal but if there is any abnormality found it would be investigated appropriately and the most appropriate treatment would be given to improve upon the general condition of the patient.

c. Biochemistry blood tests

• Serum urea and electrolytes; blood glucose; and liver function tests are routine tests that are undertaken as part of the general assessment of patients who have primary intrascrotal osteosarcoma and most often the results would be normal but if there is any evidence of an abnormality with regard to any of the tests it would be thoroughly investigated and the an appropriate treatment would be given to improve the general condition of the patient.

• Serum Beta Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin; Alpha Fetoprotein; and Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) are general tests undertaken in testicular tumors to exclude Germ Cell Tumors of the testis.

d. Radiology investigations

• It has been stated that generally; radiology imaging of the scrotal contents would tend to show heterogeneous intratesticular solid mass which tends to contain calcifications [4]

e. Chest x-ray

• Chest x-ray is a general screening investigation that can be taken in the initial assessment of patients to be sure they do not have pulmonary metastases and as part of the followup assessment to exclude pulmonary metastasis. However; utilization of chest x-ray has been superseded by CT scan and MRI scan of thorax; abdomen and pelvis in the initial staging and follow-up assessment of patients who have primary intrascrotal osteosarcomas

f. Ultrasound scan

• Ultrasound scan of the scrotal contents would define the lesion in the testis or within the para-testicular area and would tend to reveal a heterogeneous mass within the testis or within the scrotum related to the site of the lesion. The size of the lesion and its relation to the surrounding structures would be shown by the ultrasound scan. Even though contrast enhanced ultrasound scan (CEUS) is not undertaken in most centres; in centres where contrast enhanced ultrasound scan is undertaken the ultrasound scan would also show contrast enhancement of the testicular or intra-scrotal lesion in addition to evidence of calcification.

• Ultrasound scan of abdomen and pelvis and renal tract could be done as part of the general assessment / staging of the tumor to ascertain if there are metastases within the abdomen and pelvis including lymph node involvement by the tumor.

• Ultrasound scan of scrotum plus abdomen and pelvis can be done as part of the regular follow-up assessment of patients who have undergone radical orchidectomy or radical orchidectomy plus en bloc excision of a para-testicular osteosarcoma to ascertain whether or not the individual has developed metastasis.

g. Computed tomography (CT) scan

• CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis and scrotal contents would show calcification in a lesion that may be in the testis; or within the scrotal lesion where the tumor is as well as a heterogenous lesion in the area of the tumor. The CT scan would demonstrate the location and size of the lesion as well as its relation to the surrounding structures; presence or absence of enlarged lymph nodes within the pelvis retroperitoneum; or para-aortic regions as well as presence or absence of metastasis within the abdomen in any of the abdominal organs. If there is any synchronous tumor elsewhere in the abdomen and pelvis the CT scan would show it.

• CT scan of thorax; abdomen; and pelvis can be undertaken as part of the initial staging of the osteosarcoma and also to illustrate that that there is no other tumor anywhere else that could constitute a primary osteosarcoma with the tumor within the scrotum being a metastatic lesion. Additionally CT Scan of thorax; abdomen; and pelvis tends be undertaken regularly as part of the follow-up assessment of patients who have undergone surgical treatment for intra-scrotal primary osteosarcomas.

h. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

• MRI scan of the abdomen and pelvis and scrotal contents would show calcification in a lesion that may be in the testis; or within the scrotal lesion where the tumor is as well as a heterogenous lesion in the area of the tumor. The MRI scan would demonstrate the location and size of the lesion as well as its relation to the surrounding structures; presence or absence of enlarged lymph nodes within the pelvis retroperitoneum; or para-aortic regions as well as presence or absence of metastasis within the abdomen in any of the abdominal organs. If there is any synchronous tumor elsewhere in the abdomen and pelvis the MRI scan would show it.

• MRI scan of thorax; abdomen; and pelvis can be undertaken as part of the initial staging of the osteosarcoma and to illustrate that that there is no other tumor anywhere else that could constitute a primary osteosarcoma with the tumor within the scrotum being a metastatic lesion. Additionally, MRI Scan of thorax; abdomen; and pelvis tends be undertaken regularly as part of the follow-up assessment of patients who have undergone surgical treatment for intra-scrotal primary osteosarcomas.

i. Positron emission tomography (PET-CT) scan

• PET-CT scan can be done as part of the follow-up assessment of patients who have undergone treatment for intra-scrotal osteosarcomas, but this has been superseded by CT and MRI scans of thorax; abdomen and pelvis.

j. Isotope bone scan

• Isotope bone scan tends to be undertaken to confirm or negate presence of bone metastasis.

Treatment

• Treatment of primary osteosarcoma of the testis whether it is diagnosed pre-operatively from biopsy of the lesion or is being treated as a testicular tumor without knowing the type testicular would tend to be by radical orchidectomy.

• Para-testicular osteosarcoma would tend to be associated with radical orchidectomy with en bloc complete excision of the extra-testicular or para-testicular lesion.

• If there is evidence of metastasis then adjuvant chemotherapy plus or minus adjuvant chemotherapy could be given but considering that some osteosarcomas develop many years after radiotherapy has been given to organs adjacent to the site of the osteosarcoma some clinicians could prefer adjuvant chemotherapy.

a. Macroscopic features: Macroscopic examination of specimens of an excised osteosarcoma of the testis would tend to show a wellcircumscribed; firm; solid; whitish tan; expansile mass which had compressed the surrounding parenchyma of the testis [4].

b. Microscopic features

• It has been stated that microscopic examination of primary osteosarcoma of the testis specimen would tend to show sheets of pleomorphic round to spindle cells that contain prominent nucleoli [4].

• It has also been stated that microscopic examination of osteosarcoma of the testis would also show areas of osteoid and scattered areas of mineralization [4].

• Additionally, it has been documented that microscopic examination of osteosarcoma of the testis would reveal high mitotic activity and atypical mitosis [4].

• Furthermore; it has been iterated that microscopic examination of osteosarcoma of the testis would show osteoclasts among the area of osteoid [4].

c. Immunohistochemistry features

i. Positive staining: Strong cytoplasmic positivity for Vimentin [6].

ii. Negative staining

• Pan CK

• EMA

• SMA

• Desmin

• Bc12

• CD99

• CD117

• CD30

• Alfa fetoprotein

• NSE

• NF1

• S100

• PGP9.5

d. Molecular and genetics studies: It has been stated that in primary osteosarcoma of the testis; re-arrangement of p53 at 17p13 could be of importance in oncogenesis of osteosarcoma [2].

e. Prognostic factors: It has been stated that primary osteosarcomas of the testis that are confined to the testis tends to be associated a favorable prognosis [4].

f. Differential diagnoses: Some of the documented differential diagnoses include: [4]

• Metastatic osteosarcoma of testis [4].

• Sex cord / stromal tumor with sarcomatous transformation [4].

• Teratoma with sarcomatous transformation [4].

• Malignant neural tumor of testis. [4].

• Leiomyosarcoma of testis [4].

• Synovial sarcoma of testis [4].

g. Outcome

With regard to the outcome of patients who have had radical orchidectomy for osteosarcomas of the testis and radical orchidectomy plus en bloc excision of para-testicular localized primary osteosarcomas short term and medium-term survival without local recurrence and metastasis has been reported with up to 44 months survival but because few cases have been reported without long term follow-up one cannot be dogmatic about the long-term outcome of the disease. It is known that osteosarcomas can recur 11 years after an apparent complete and successful treatment it would be envisaged that unless adjuvant combination chemotherapy is utilized in the initial treatment of a localized primary intra-scrotal osteosarcoma there is the likelihood that late metastases of osteosarcoma could develop. Clinicians should be encouraged to report cases of osteosarcomas of scrotal content organs they treat in order to elucidate the biological behaviour of the disease with the knowledge that most cases of primary osteosarcomas of other organs have generally portended a poor prognosis.

Miscellaneous narrations; summations and discussions from case reports; case series; and studies related to osteosarcoma of the testis

Zukerberg LR and Young RH [7] reported the clinical and pathology features of two cases of pure sarcomas of the testis. They reported that one tumor was an osteosarcoma which was found in a 30-year-old man; and the second case was a fibrosarcoma which was found in an 86-year-old man. Both patients were treated by means of orchidectomy and high ligation of the spermatic cord and they did not receive any post-operative adjuvant therapy. Both patients were reported to be alive and well without any evidence of local recurrence or metastasis at 6 months and five and half months respectively pursuant to orchidectomy. The authors stated that majority of sarcomas of the testis do arise from a teratoma; or less commonly they tend to arise from a spermatocytic seminoma; nevertheless; their two cases and rare reported cases had shown that pure sarcomas do occur occasionally and they could be associated with a favorable prognosis. It could be argued that the two cases were reported with a short period of follow-up only and hence the long-term outcome of both patients was not available. It would also be argued that this case report is not strong enough to make any confident statement related to the outcome of osteosarcoma of the testis and some clinicians could also argue that considering that primary osteosarcomas elsewhere in the body tend to be associated with poor long-term outcome the patient who had primary osteosarcoma of the testis should have been considered for adjuvant chemotherapy to ensure his long-term survival.

Tazi H, et al. [2] reported the case of primary osteosarcoma of the testis in a 60-year-old man who was treated by means of transinguinal orchidectomy without any adjuvant therapy. The reported patient was alive and well without any evidence of local recurrence or metastasis at his 18-month post-operative follow-up. Tazi H, et al. [2] stated that 2at the time of report of their case only 3 cases of primary osteosarcoma of the testis had been reported. Tazi H, et al. [2] additionally stated that the origin of primary osteosarcoma of the testis from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells or from a malignant transformation of a pre-existing teratoma element was not clear as well as management guidelines of osteosarcoma of the testis are difficult to establish in view of the rarity of such tumors; nevertheless; in their opinion inguinal orchidectomy with careful follow-up would appear to be sufficient treatment for the tumor. Some people would argue that the case was reported with 18 months follow-up only and hence the long-term outcome would not be known and perhaps the patient should have been offered adjuvant chemotherapy with the aim of destroying any possible microscopic metastases that could develop into overt clinical metastasis in the future. Considering that there is no consensus opinion related to the treatment of primary osteosarcoma of the testis and the fact that primary osteosarcomas elsewhere generally have been associated with poor prognosis pursuant to surgical excision some people would argue that there is an urgent global need for the establishment of a multi-centre trial of different treatment options with a long-term follow-up in order to ascertain the best treatment options for localized and metastatic osteosarcomas of the testis.

Hong R, et al. [3] reported a 78-year-old man who had presented with a right hemi-scrotal swelling. He had ultrasound scan of scrotal contents which showed a hydrocele and a heterogeneous solid mass with focal calcification in his right testis. He underwent right inguinal orchidectomy and pathology examination of the specimen confirmed a diagnosis of osteosarcoma of testis. He also underwent retroperitoneal lymph node dissection and pathology examination of the specimen did not show evidence of any tumoral metastasis. Upon thorough examination of the tumor there was no evidence of any additional histological components of tumor. He remained well without any evidence of local recurrence or metastasis at his 44-month post-operative follow-up. Hong R, et al. [3] stated the following:

• Primary osteosarcoma of the testis is a rare malignancy.

• Up to the time of the report of their case only two cases of primary osteosarcoma of the testis had been reported.

• They had reported the 3rd case of primary osteosarcoma of the testis which in their case was complicated a hydrocele.

• It was unlikely that their case did arise from teratoma or mixed sex-cord / stromal tumor in view of the fact that no other neoplastic tumoral elements had been found in whole sampling of the tumor.

• Their case had shown that primary pure testicular osteosarcoma could be associated with favorable prognosis.

Some people would state that it was re-assuring that the patient was alive at his 44-month post-operative follow-up but considering that some tumors do metastasis after a period of time longer than 44 months the long term outcome of the disease could not be known and perhaps the patient should have been offered adjuvant combination chemotherapy which is aimed at the destruction of possible microscopic metastases that may grow slowly and manifest in an overt clinical disease after a long time. There is no quick answer to this dilemma and for this reason a global multicentre trial of various treatment options for primary osteosarcoma of the testis should be established. Considering the rarity of the disease it would be a good idea if a global sarcoma group could establish a data base of primary osteosarcomas of the testis that have been reported and they should also subsequently at regular intervals obtain further outcome reports related to all cases that had been reported in order to understand the biological behaviour of the malignancy affecting the testis.

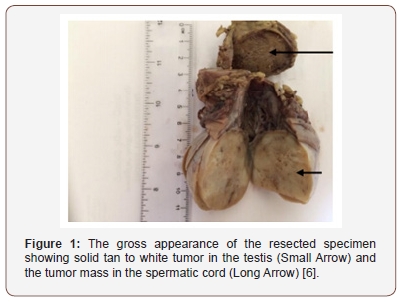

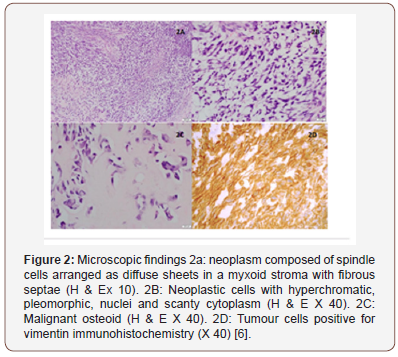

Mathew T and Prabhakaran K [8] reported a case of osteosarcoma of testis. They stated that the tumor either did originate from indifferent mesenchymal cells or it did represent a one-sided monomorphic development of a teratoma. reported a 73-year-old previously healthy man who presented with a painless scrotal lump of 2 months duration [6]. He was asymptomatic otherwise and he did not have any significant past medical history or family history. His general and systematic examinations were normal; He was otherwise found to have a few enlarged right sided inguinal lymph nodes. His scrotal examination revealed a right testicular hard mass which measured 3.5cmx3.4cm, and which did not trans-illuminate. The results of his routine full blood count; liver function tests; renal function test; and chest x-ray were normal He had abdominal ultrasound scan which was normal. He had scrotal ultrasound scan which revealed a solid heterogeneous mass which did measure 3.5cmx3cmx4cm which was suspicious for malignancy. He underwent right trans-inguinal radical orchidectomy without any post-operative problems. He was however; lost to followup. Gross macroscopic examination of the specimen showed a testis that measured 4cmx2.2cmx2.cm; epididymis that measured 4cmx1.8cmx1cm; and spermatic cord that measured 8 cm. The cut sections of the specimen revealed a solid tan to white tumor that measured 3.5cmx2.5cmx2cm with spotty necrosis. The tunica albuginea and tunica vaginalis looked normal. The spermatic cord contained a similar mass that measured 3cmx2.4cmx2cm which was located 1 cm proximal to the end of resection site (Figure 1). Microscopy examination of the testicular tumor showed a tumor which comprised of spindle cells that had been arranged as diffuse sheets of within a myxoid stroma that contained fibrous septa (Figure 2A). The tumor cells did contain hyperchromatic; pleomorphic nuclei and scanty cytoplasm (Figure 2B). Upon extensive sampling of the tumor; focal areas of osteoid visualized (Figure 2C). Mitotic activity and foci of necrosis were visualized. There was evidence of infiltration of the epididymis. The spermatic cord tumoral mass revealed a morphology that was like that of the testicular tumor which was suggestive of tumor deposit from the testicular tumor. Microscopic examination of the tumors did not reveal any elements of germ cell tumor or sex cord stromal tumor. The resection margin of the spermatic cord and tunica albuginea were normal. Very atrophic testicular tissue was visualized focally. Immunohistochemistry staining studies of the tumor showed strong cytoplasmic staining for vimentin in the tumoral cells (Figure 2D). Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumors showed that the tumor cells had stained negatively for: Pan CK; EMA; SMA; Desmin; Bc12; CD99; CD117; CD30; Alfa fetoprotein; NSE; NF1; S100; PGP9.5. A diagnosis of primary osteosarcoma of the testis with tumor deposits in the spermatic cord was made. Some people would argue that considering that primary osteosarcomas of organs elsewhere; the fact that with regard to the reported case there was evidence of testicular osteosarcoma deposits in the spermatic cord the patient should have been offered adjuvant chemotherapy, but the patient was lost to follow-up.

Resorlu B, et al. [9] reported a 63-year-old man who had presented with a large painless left inguinal left inguinal and scrotal mass. His clinical examination showed a palpable large hard mass which had involved the left groin and scrotum. He had ultrasound scan which showed a 16 cm heterogeneous solid mass within his left testis which was suggestive of left testicular tumor. The results of his serum alpha fetoprotein; and serum beta human chorionic gonadotrophin levels were within normal range. He underwent trans-inguinal left radical orchidectomy with high ligation of the spermatic cord. Macroscopic pathology examination of the specimen revealed a capsulated tumor which had arisen from the left testis and which was in continuity with the left spermatic cord. Microscopic examination of the sections of the testis revealed a highly vascular tumor that had osteoid and bone formation. The tumor was visualized as extremely cellular and as containing round to spindle cells that exhibited nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli; frequently that had demonstrated atypical mitotic figures. Normal testicular tissues were visualized adjacent to the tumoral lesion. The tumor was diagnosed as osteosarcoma with negative surgical margins which did not contain tumor at the surgical margins. He had various radiology imaging including isotope bone scan which did not reveal any malignancy anywhere else in the body that could constitute a primary tumor. He was well at his 12-month follow-up without any clinical or radiology imaging evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis. Even though there was no evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis at his 12-month pot-operative follow-up; it could be argued that the case was reported with a short follow-up and no one would know the long-term outcome of the individual. Some clinicians would also argue that the patient who had such an extensive tumor should have been considered for adjuvant chemotherapy. The solution to the dilemma of what the best treatment option for primary osteosarcoma of the testis would require establishment of a global multi-centre trial of various treatment options including radical orchidectomy alone and radical orchidectomy plus various combination chemotherapy medicaments.

Para-testicular osteosarcomas: Hong R, et al. [3] reported a 52-year-old man who had complained about a painless swelling and a palpable in his left hemi-scrotum which had steadily enlarged over a period of one year. His clinical examination revealed a hard and non-tender mass within his left hemi-scrotum. A provisional diagnosis of testicular tumor was made. He had a CT scan of the pelvis which showed a large para-testicular mass which contained calcification and internal necrosis in his left hemi-scrotum that had displaced his left testis inferiorly. There was no evidence of any enlarged lymph node. He had ultrasound scan of the scrotal contents which showed a heterogeneous mass within his left hemi-scrotum and the features of the mass was reported as being consistent with sarcoma of the left spermatic cord. He did undergo left orchidectomy. The specimen measured 14.0cm x 5.5cm x 5.0cm and this contained the left testis; left spermatic cord; and a grey tan coloured mass. Upon sectioning the mass was found to measure 6.5 cm x 5.0 cm and it had displaced the left testis inferiorly. The tumor mass was well-circumscribed by a thick fibrous capsule which was firm and solid and had focal necrosis as well as haemorrhage. The testis; spermatic cord and epididymis were intact. Microscopic histopathology examination of the specimen showed that the tumoral cells were very cellular and they contained spindled or polyhedral cells which were cytologically atypical and mitotically active as well as frequently revealing atypical mitotic figures. Portions of osteoid and marked bone differentiation were frequently visualized. Immunohistochemistry studies showed that the tumor cells had stained positively for vimentin, but the tumor cells had stained negatively for: smooth muscle actin; CD34; cytokeratin; desmin; inhibin; myo-D1; and S-100 proteins. A diagnosis of extraosseous para-testicular osteosarcoma was made. At his 9-month follow-up he was well without any evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis. Hong R, et al. [3] stated that extra-osseous para-testicular tissue osteosarcoma was a very rare tumor and that with the exception of their reported case; only one other case of extra-osseous osteosarcoma originating from the para-testicular soft tissue had been reported previously. It could be argued that the case was reported with only 9 months follow-up information and that the long-term outcome was not available and considering that late metastasis could develop adjuvant chemotherapy could have been given or offered to the patient with the hope that if there are microscopic metastases they would be destroyed completely before they get the chance to develop into overt clinical disease. Al Masri A, et al. [10] reported a 52-year-old man who presented with a painless left hemi-scrotal mass which had been steadily enlarging over a period of 4 months. The mass had extended into the left groin in the weeks preceding his presentation. He did not have any significant past medical history and he had not had any trauma. His clinical examination did reveal a hard; non-tender; and irregular left hemi-scrotal mass which had extended into the left inguinal region. The right testis was normal. A provisional diagnosis of chronic left testicular hematoma was made. He had whole body imaging studies which were normal. He underwent trans-inguinal left orchidectomy without dissection of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Pathology examination of the specimen showed features of para-testicular osteosarcoma. He received subsequently combination chemotherapy which included: cisplatin; doxorubicin; and methotrexate. He died after 6 months with extensive retroperitoneal lymph node metastases and inoperable intestinal obstruction. Macroscopic pathology examination of the specimen showed that the specimen had comprised of a haemorrhagic nodular mass that measured 17cm x 10cm x 10cm with an attached testis that measured 7cm and a spermatic cord that measured 8cm. Upon sectioning showed a well-circumscribed mass which was firm; solid; and grey tan with extensive areas of necrosis. The testis; epididymis; and the spermatic cord were normal. Microscopic examination of the specimen showed a highly vascular tumor with formation of osteoid and bone. There was also evidence of extensive necrosis. The tumor was very cellular with large; anaplastic; roundto- spindled-cells that had eosinophilic cytoplasm; vesicular nuclei; and conspicuous nucleoli. The tumor did contain many multinucleated giant cells as well as high mitotic activity. The testis; epididymis; and spermatic cord upon histopathology examination were found to be normal. The histopathology features of the tumor were consistent with those of a pure para-testicular osteosarcoma with evidence of vascular invasion as well as all resection margins were free of tumor. It would be argued that the patient was treated appropriately with radical orchidectomy and combination chemotherapy, but the patient died as a result of metastasis within 6 months. This would mean that the chemotherapy medicaments were not effective in destroying microscopic metastases that were present in tissues at the time of the orchidectomy and for this reason it would be recommended that urologists; oncologists; and pharmacotherapy research workers should identify as well as help develop chemotherapy medicaments that will effectively destroy osteosarcoma tumor cells in order to prolong the longterm outcome and quality of life of patients who have primary and metastatic osteosarcomas.

Taleb F, et al. [11] reported a 61-year-old man who presented with a 6 months history of a hard; left intra-scrotal mass; which had gradually increased in size. His clinical examination revealed a hard-left intra-scrotal mass that had irregular contours, and which was adherent to the left hemi-scrotal wall without any sign of associated inflammation. The right testis on examination was found to be normal. He had ultrasound scan of the scrotal contents which showed a heterogeneous mass in the left hemi-scrotum and the left testis could not be seen separately from the mass. He had CT scan which showed a heterogeneous mass that measured 11.9 cm x 10.6 cm in the left para-testicular region that was hyperdense and which showed moderate contrast enhancement. The left hemi-scrotal mass was contiguous with the left hemi-scrotal wall and the left testis. The testis looked regular and homogeneous. He underwent total excision of the mass together with left orchidectomy which was followed by adjuvant radiotherapy. Gross examination of the specimen showed a white pearly tumor that measured 12cm x 9.5cm and which was calcified in about 90% of its volume. The left testis was visualized at the periphery of the tumor. Microscopic histopathology examination of the tumor showed the mesenchymal nature of the tumoral mass with marked cartilaginous bone differentiation. There were areas of invasion of invasion of the peripheral capsule. The residual testis was fibrotic. A diagnosis of well-differentiated osteosarcoma was made. Unfortunately, the long term outcome was not available in the article. It is known that some patients who had previously undergone radiotherapy to tumors in other organs subsequently many years later do sporadically develop other malignancies in organs that were in the radiation field and that osteosarcoma has occasionally developed many years after individuals have undergone radiotherapy to other organs. There is an urgent need for urologists; oncologists; and pharmacotherapy research workers to define the role of radiotherapy in osteosarcoma of the testis. Stella M, et al. [12] reported a 59-year-old man who presented with a large; painless; left inguinal as well as left hemiscrotal mass. He did undergo excision of the mass which had arisen from the spermatic cord. A left sided high dissection of the spermatic cord and radical left orchidectomy was in view of associated atrophy of the left testis. Pathology examination of the tumor showed features that were diagnostic of osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord. The patient died 11 years later due to metastatic lung disease. Stella M, et al. [12] stated the following:

• Osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord is a rare neoplasm and its preoperative diagnosis is difficult.

• Any palpable suspicious mass of the spermatic cord must be investigated with ultrasound scan preceding excision of the mass.

• CT scan MRI scan could be beneficial with regard to defining pre-operative diagnosis and extension of the mass into the surrounding tissues.

• Surgical treatment of sarcomas of the spermatic cord in adults is through a radical orchidectomy with high dissection of the spermatic cord as well as en bloc excision of in the involved surrounding tissues.

• The overall and 5-year; and 10-year survival rates had been reported in the literature to be 75% and 55% respectively.

The fact that the patient died 11 years following undergoing radical and complete excision of a primary osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord would indicate that at the time of the surgical operation there were microscopic metastases which could not be identified by means of radiology imaging and these microscopic metastases grew slowly to emanate in overt clinical disease ;many years later and in view of this it would be argued that it would be more beneficial if appropriate and effective adjuvant chemotherapy could be added to the radical excision surgery with the aim of destroying possible microscopic metastases and preventing them from developing into overt clinical disease. Spirtos G, et al. [13] in 1991 reported a patient who had osteosarcoma which had arisen in his left spermatic cord. He underwent left radical orchidectomy with high dissection of the spermatic cord. The patient was alive without any local recurrence or distant metastasis at his 2-years follow-up. Spirtos G, et al. [13] stated that they could not find any previous discussion or report on primary osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord. Considering that metastases can occur many years following an apparently complete surgical excision of osteosarcomas without any evidence of tumor at the resection margin and considering that this case was reported with only 2-year follow-up; one cannot know what the long-term outcome would be. It could therefore be argued that perhaps the patient should have been considered for appropriate and effective adjuvant chemotherapy

Beiswanger JC, et al. [14] reported a patient who had primary osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord which was associated with synchronous bilateral renal cell carcinoma. They stated that primary extra-skeletal osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord is uncommon and that only two other cases had been reported in the global literature at the time of publication of their article. This case report is important due to the fact that malignancies had been found in the spermatic cord as well as in both kidneys. The question that needs to be answered if there are any common genetic abnormalities within the individual which had predisposed the individual to develop the three tumors or it was an incidental scenario.

Ugidos L, et al. [15] reported a case of spermatic cord sarcoma (SCS) that contained mixed differentiation of tumors that included liposarcoma and osteosarcoma elements. Ugidos L, et al. [15] stated that spermatic cord sarcomas are not frequently found and that at times they tend to be mis-diagnosed tumors and additionally; the optimum management of spermatic cord sarcomas does remain undefined with ongoing controversy remaining with regard to indications for adjuvant therapy of the sarcoma tumors of the spermatic cord. They further stated that with regard to histopathology examination of sarcomas of the spermatic cord; liposarcomas tend to be the commonest type of tumor encountered and that it is only on rare occasions that osteosarcomas of the spermatic cord are encountered and additionally; the findings of mixed tumors of the spermatic cord containing both liposarcoma and osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord had never been reported prior to the report of their case. An important lesson to be learnt from this case report is that on rare occasions if osteosarcoma elements are visualized on microscopic examination of a spermatic cord tumor pathologists would need to thoroughly search the tumor to establish whether or not there is an element of another type of sarcoma as well as when a liposarcoma is found in microscopic examination of a spermatic cord tumor the pathologist also needs to carefully examine the specimen thoroughly to ascertain if there is an element of osteosarcoma anywhere within the tumor.

Conclusion

Primary osteosarcoma of the testis and scrotal contents including the para-testicular organs are extremely rare malignancies that have sporadically been reported. Most of these cases have been reported with short-term and medium-term survival following radical orchidectomy plus or minus radical orchidectomy plus en bloc excision of relevant tumors but long-term follow-up data is not available globally. Considering that primary osteosarcomas can recur many years after an apparently successful complete excision of osteosarcomas that afflict other organs outside the scrotum clinicians should be encouraged to include adjuvant chemotherapy to radical orchidectomy plus en bloc excision of all intra-scrotal primary localized osteosarcomas as an aim to prevent the subsequent development of late local recurrences and metastases. Intra-scrotal osteosarcomas with metastases should be treated aggressively by means of radical orchidectomy plus / minus en bloc excision of the tumors plus combination adjuvant therapy which should at least include combination chemotherapy taking into consideration that utilization of radiotherapy would be debatable or controversial.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- Russo P, Brady MS, Conlon K, Hajdu SI, Fair WR, et al. (1992) Adult urological sarcoma. J Urol 147(4): 1032-1036.

- Tazi H, Karmouni T, Ouali M, Koutani A, Hachimi M, et al. (2006) Osteosarcoma of the testis. Int J Urol 13(3): 323-324.

- Hong R, Lee G, Kim H, Kim CS, Kee KH (2012) Primary paratesticular osteosarcoma: A case report. Oncol Lett 3(3): 554-556.

- Gordetsky J (2014) Testis and epididymis Germ cell tumours Osteosarcoma.

- Lee JS, Choi YD, Choi C (2004) Primary testicular osteosarcoma with hydrocele. Virchow Arch 445(2): 210-213.

- Ranawaka RAAU, Siriweera EH (2017) Primary Testicular Osteosarcoma: A rare case. Journal of Diagnostic Pathology 12(2): 26-29.

- Zukerberg LR, Young RH (1990) Primary testicular sarcoma. Hum Pathol 21(9): 932-935.

- Mathew T, Prabhakaran K (1981) Osteosarcoma of the testis. Arch Path Lab Med 105(1): 38-39.

- Resorlu B, Onem K, Germiyanoglu RC (2018) Primary testicular osteosarcoma. Urologia 85(2): 44-45.

- Al Masri A, Al Shraim M, Al Samen AA, Chetty R, Evans A (2007) Primary Testicular Osteosarcoma: Case Report and a Review of the Literature. The Scientific World Journal 7: 850-854.

- Taleb F, Kyari A, Hamid K, Bouklata S, Hmmani L, et al. (2007) Osteosarcoma extraosseous paratesticular localization: about a case, Extra-large osteosarcoma in paratesticular renting: case report. J Radiol 88: 401-402.

- Stella M, Somma CD, Solani N, Nozza P, Meszaros P, et al. (2007) Primary Osteosarcoma of the Spermatic Cord: Case Report and Literature Review. Anticancer Res 37(3B): 1605-1608.

- Spirtos G, Abdu RA, Schaub CR (1991) Osteosarcoma of the Spermatic Cord. J Urol 145(4): 832-833.

- Beiswanger JC, Woodruff RD, Savage PD, Assimos DG (1997) Primary osteosarcoma of the spermatic cord with synchronous bilateral renal cell carcinoma. Urology 49(6): 957-959.

- Ugidos L, Suárez A, Cubilo A, Durán I (2010) Mixed paratesicular liposarcoma with osteosarcoma elements. Clin Transl Oncol 12(2): 148- 149.

-

Anthony Kodzo Grey Venyoi. Primary Osteosarcoma of Testis and Para-Testicular Tissues: A Review and Update of the Literature. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 1(3): 2019. AUN.MS.ID.000512.

-

Algeria, Acute peritoneal dialysis, Children, Dialysis emergencies, Nephrology, Kidney injury, Hemolytic and Uremic syndromes

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.